Before we start digging into the game’s main text and such, there are a few interesting things about the game itself that deserve a look!

Booting Up

When you turn the power on, the NES version goes immediately to the game’s title screen.

The Famicom Disk System is different though – it has a whole bunch of stuff that displays before the game loads. This actually applies to all FDS games though, not just Zelda. Here’s what it’s like, for those of us who never grew up with a Famicom Disk System:

Title Madness

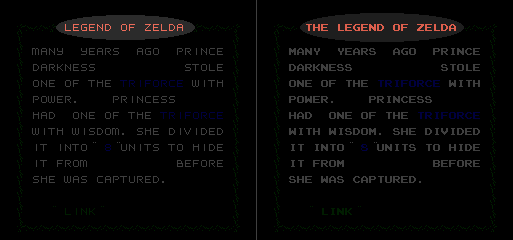

There’s actually a slight thing with the name of the game that many might not be aware of – the game is called “Legend of Zelda” in Japan but “The Legend of Zelda” in the NES version.

|

This added “the” was also included on the NES version’s box, cartridge, manual, and all that too, so at some point someone on the localization team said, “Hey, make extra sure to include ‘The’ in everything!”

|

I imagine it would’ve been very easy for something this small to get inconsistent treatment, so whoever wanted the “The” added was clearly very detail-oriented.

Intro Story

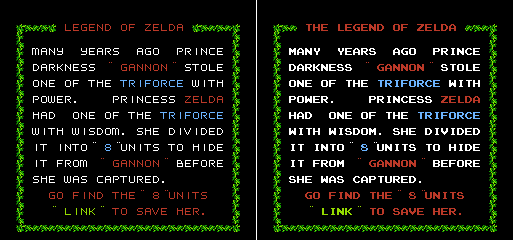

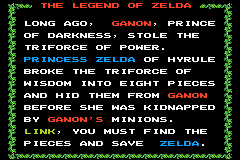

After the title screen, a little intro starts up, and the first thing we see is the game’s story. It turns out the story is exactly the same in both games – it’s even written in English in the Japanese version!

|

Seeing this brings many questions to mind:

Question #1: Why does the Japanese story use English instead of Japanese?

I already covered this briefly on this page of my Super Mario Bros. analysis, but there are basically a number of reasons why this happens.

First, English is a required subject in the Japanese school system, so everyone gets a couple years of exposure to the language. Mostly it’s a lot of rote memorization of vocab lists, so it’s not entirely useful. But it means that Japanese people can still pick out words they recognize when confronted with a wall of English text.

Second, English words are used all the time in Japanese. If you study Japanese, you’ll immediately learn that a good percentage of common Japanese words are actually taken from English. So English is right at home in Japanese entertainment.

Third, English has an interesting allure to it in Japan. You know how Americans love to get Japanese/Chinese characters for tattoos, even if they don’t really know what they mean or how to pronounce them? This is kind of like that, but times a million. If you walk around any Japanese street or go into any Japanese store, you’ll find English everywhere.

|

There are also often technical advantages of using English instead of Japanese – you only need memory for 26 letters if you use English, but well over a hundred if you decide to use Japanese katakana and hiragana.

A side result of this is that many games released in 1980s Japan used English text. So where we English-speakers fondly view retro games as having poorly-written English, Japanese retro games have an “oh, all the text is in English” vibe instead.

|

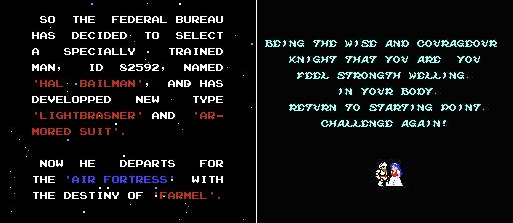

Another thing to note is that all the keywords in the Zelda story are highlighted in some way. This is somewhat common, as you can see in the Air Fortress screenshot above, and if you play any of the other Zelda games.

The color coding in Zelda’s case isn’t accidental, either – all the stuff relating to the Triforce is in blue, the Gannon/Princess stuff is in red, and the part about Link is in green. This means that even if players (of any country) aren’t very good at English, they know exactly what words they should focus on and possibly how they’re connected – enough to get the gist of the game’s goal, in other words.

Lastly, the Japanese manual explains the game’s story and all that in Japanese, so this intro can be seen as more of an added decoration than anything.

Question #2: Why is it still in poor English in the NES version?

Honestly, that’s anyone’s guess. It’s strange, as some of the text in the game is handled superbly, but some of it, like this, makes you wonder how anyone approved it for English-speaking countries. We’ll take a closer look at some of these good and bad translation examples in a little bit.

Question #3: Gannon?

As far as I know, this is the only time the villain’s name is spelled “Gannon” – even the NES manual spells it as “Ganon”. The Japanese name is ガノン, which is transcribed literally as “Ganon”. Where the extra “n” comes from is a mystery, but since it was in the Famicom Disk System version first it was most likely someone on the Japanese side who added it in.

|

So why didn’t they change it for the NES version? That’s yet another mystery. It almost sounds like the localizers didn’t even pay attention to this intro, but later on we’ll see that they DID pay attention to it. What a puzzle…

As a side note, the story and some of the game’s text was given a makeover in later English ports. Here’s what the story looks like in the GBA version:

|

Load Times in My Zelda?

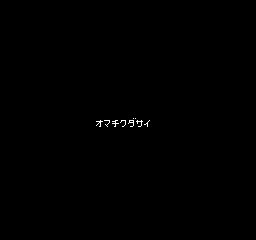

Since we’re looking at the Famicom Disk System version of Zelda, it should come as no surprise that the game often has to sit and load new data during parts of the game. It’s interesting that even these old, primitive console games had loading times.

In contrast, everything loaded super-fast in the NES version – no loading screens or anything for us!

|

The above screen is the “Please Wait” loading screen used in the FDS version of the game.

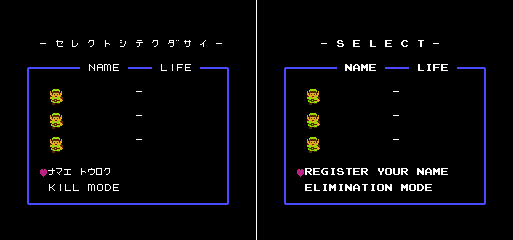

File Selection

After the title screen, you’re taken to the file select screen. This screen is slightly different in both versions.

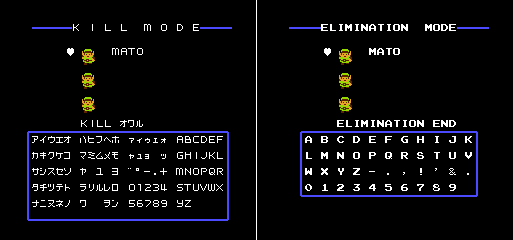

The biggest difference is that the file deletion option is called “Kill Mode”, while in the NES version it’s called “Elimination Mode”.

It’s clear Nintendo didn’t like the idea of “kill” being used here, but it also just makes more sense to call it “elimination”. Personally, I think calling it “Delete a save” would’ve been better, as “kill mode” and “elimination mode” almost sound like special bonus modes without any added context.

|

Also, this style of file and naming system was apparently standard on Famicom Disk System games that saved data. Which might account for why some other games that came out later seemed to have a file and naming system that looked just like this game’s.

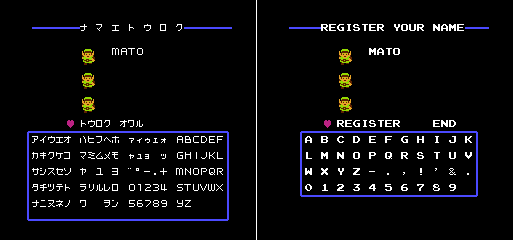

Name Yourself

In both versions of the game you have to name yourself, and that name is attached to the selected save file.

|

As you can see, the screen is slightly different in the Japanese version. It allows for a lot of other characters, mostly Japanese katakana. The NES version adds in various punctuation, though.

This screen (and the file select screen) is the first time we see heavy Japanese text usage in the Japanese version. Ah, so it’s not all English after all!

Kill Yourself?

We already looked at the “Kill Mode” difference, but here’s the actual kill mode screen for reference. The word “KILL” is used twice on the Japanese screen, probably not something American parents would like to see 😛

|

Continue to be Different

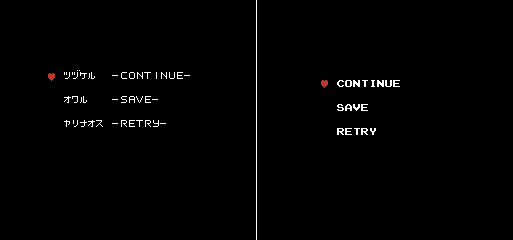

The continue/save/retry screen you get when you die (or do the special code) is slightly different in both versions.

The Japanese version includes English text alongside the Japanese text. The NES version simply has the English text, slightly repositioned.

|

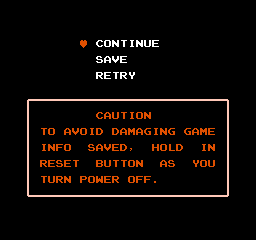

This screen was further changed in later revisions of the NES game to remind players to hold in Reset while turning the game off. I don’t know the technical reason why, it was just something they always said to do with every NES game that had battery saves.

Famicom Disk System users didn’t have to deal with this wackiness, though. I get the feeling the Japanese cartridge version didn’t require it either.

|

Inventory Time

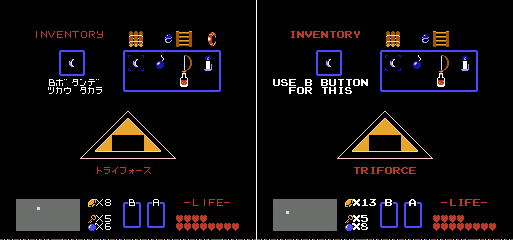

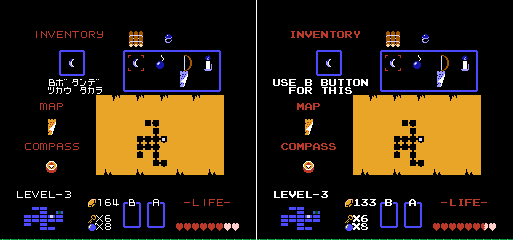

Here’s a look at the inventory screens in both games, for reference. They’re all basically the same, minus some slight text differences.

Here’s the screen when you’re walking around outside:

|

And here’s the screen for when you’re in a dungeon:

|

Incidentally, where it says “Use B Button for this” in the NES version, it says, “Treasure that can be used with the B Button” in the Japanese version.

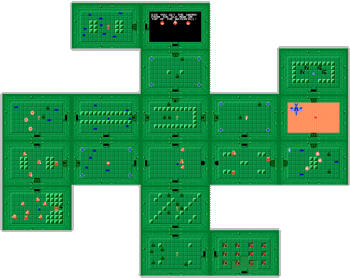

Nazi Zelda?

Level 3 of the first quest has a bit of notoriety in the West – I guess a lot of people probably mistook its shape for a swastika. Here’s a look at the full map:

|

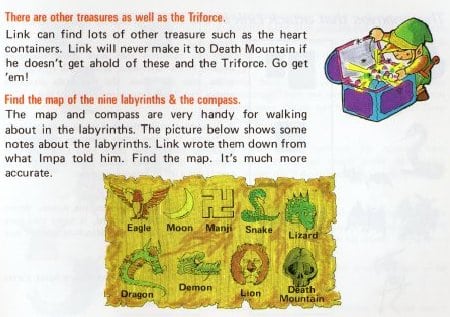

It’s pretty common knowledge by now that this is actually what’s known as a “manji”, which is a Buddhist symbol very commonly used in Japanese culture. The symbol is even used all the time on Japanese maps to mark the location of Buddhist temples.

|

In comparison, a Nazi swastika faces the other direction:

|

I’m actually surprised Nintendo’s localization team wasn’t worried about backlash from parents who didn’t know any better. But in the end I don’t think there was much outcry, if any at all. There’s also the fact that it was called a manji in the instruction manual. Who knows, maybe that even helped educate some players!

|

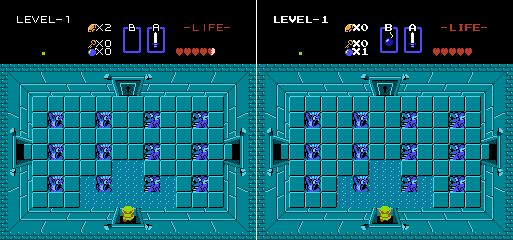

No Key Needed

There’s a trick in Level 1: walk into the level and walk back out. When you enter again, the locked door in front of you will be unlocked! I remember being excited by this when I discovered it as a kid, so I always wondered if it worked in the Japanese version too. Let’s take a look:

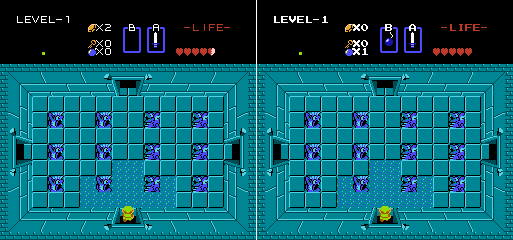

We enter Level 1 for the first time:

|

Then we leave, and come back:

|

Looks like it works in both versions after all!

Interior Decoration

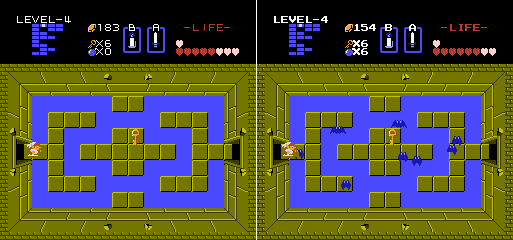

Surprisingly, there are a couple dungeon rooms that are slightly different between both versions of Zelda.

First is this room at the top of Level 4. We see that the FDS version is empty, while the NES version had a bunch of bats added for some reason.

|

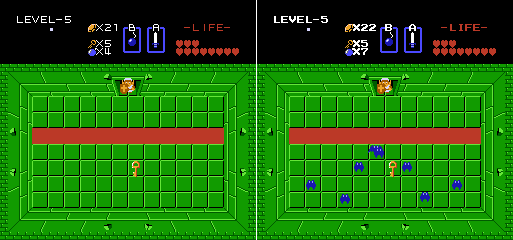

There’s also a room in Level 5 that got similar treatment:

|

I didn’t check the rooms in the second quest as carefully, so it’s possible some rooms were altered there too. If you know of any other room changes, please let me know!

Those Pesky Pols

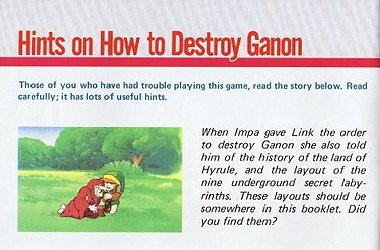

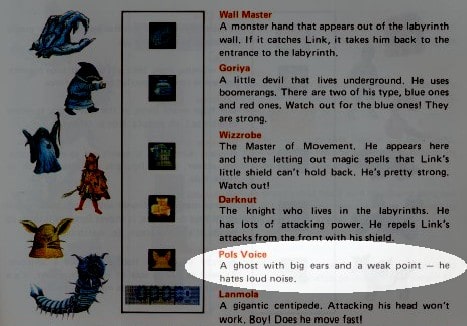

There are these weird yellow enemies in Zelda called “Pols Voices”. They have whiskers and big ears and bounce around all over the place. They’re also really tough to beat if you try to use your sword. So if you were a kid during the NES days, you probably checked the instruction manual to find info about them and came across this:

|

The manual tells you that Pols Voices are weak against loud sounds… So what’s the immediate, natural conclusion? Use the whistle/flute/recorder item! That oughta do it!

But nope, it does absolutely nothing to the Pols Voices. I remember being confused by this as a kid, thinking, “Why would the manual say that then? What else could it be talking about?” I didn’t realize at the time that there was a lot more to the story.

Basically, the Japanese Famicom system has a lot of little differences when compared with the NES. One of these differences is the controllers – the Famicom came with two controllers permanently connected to the system, and controller #2 had a built-in microphone. But when the NES was released, it was stripped of this microphone stuff.

|

So when Japanese players read that Pols Voices are weak against sound, they might’ve thought of the flute too, but astute players would’ve also thought, “Hey, I wonder what happens if I try to use the microphone on Controller #2?”

It turns out that blowing into the microphone or making enough sound will cause all the Pols Voice in a room to die instantly!

Here’s a demonstration video I recorded – I added in the sound clip so that it’d make sense since I recorded it on an emulator and not an actual Famicom.

These regional weaknesses were carried over in various ports and re-releases too, so Pols Voices are weak against arrows in all the English ports, while they’re weak against the microphone sounds in the Japanese versions.

But what about Japanese systems that don’t have microphone capabilities, you ask? At first it appears the Pols Voices have no weaknesses in these cases, but it turns out their weaknesses were changed yet again:

The Japanese 3DS version of the game is kind of nifty. You need to press L and R at the same time to bring up a controller select option, then press Y to switch to Controller 2. Then you can blow into the 3DS’ microphone to simulate the Famicom’s microphone! Here’s a demonstration:

Heart Attack!

There’s a neat glitch in the FDS version of Zelda that allows players to get lots of extra heart containers!

First, you need to have the flute. Then go to the eastern coast area, and stand left of the heart container in the ocean. Use the flute, and the tornado will pick you up and drag you across the screen. When you touch the heart container, you’ll gain an extra heart – but the heart container will still be there the next time you check!

Here’s a video I made demonstrating the trick in action:

I find that it’s not very useful in the first quest, since by the time you get the flute in Level 5 you’ve gotten a ton of hearts already and can probably already get the strongest sword in the game. But it’s very useful in the second quest, since you get the flute in Level 2. With this trick, you can get the strongest sword much more quickly than before!

As you might expect, this glitch was fixed in the NES version and all versions released afterward. Drat!

The Zelda Legends of Localization book also includes:

- New examples of English being used everywhere in Japan

- An example of how Japanese text is actually sometimes considered WEIRD in modern English-to-Japanese localizations

- More examples of “Gannon” in later Zelda games

- The legacy of the game’s file select screen

- A deeper look at the manji’s history

- A trick involving a dungeon boss

- An up-to-date look at all the ways Pols Voices are defeated in every Japanese port & re-release