A game developer friend of mine recently hired a translation agency to translate his latest game into Japanese. I offered to skim through it and make sure everything was okay… and it turned out to be a sheer disaster.

So I thought I’d write up a quick article for gamers and game developers who have dreams of releasing stuff in Japan someday.

Common Problem #1: Translating EVERYTHING

There’s a common assumption that when you translate something from English into another language, there shouldn’t be any English left when you’re done. Otherwise it would be an incomplete translation, right? And you’d feel like you got cheated out of the money you spent on translation, right?

If you’re translating into Japanese, then that assumption is wrong. English makes up a significant portion of the Japanese language today, and on top of that, English has been a major part of Japanese video games since the very beginning.

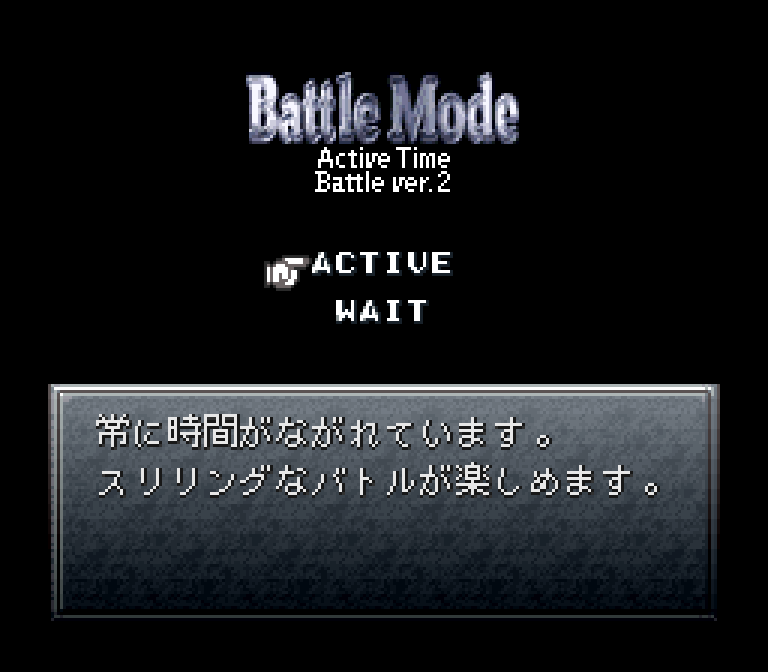

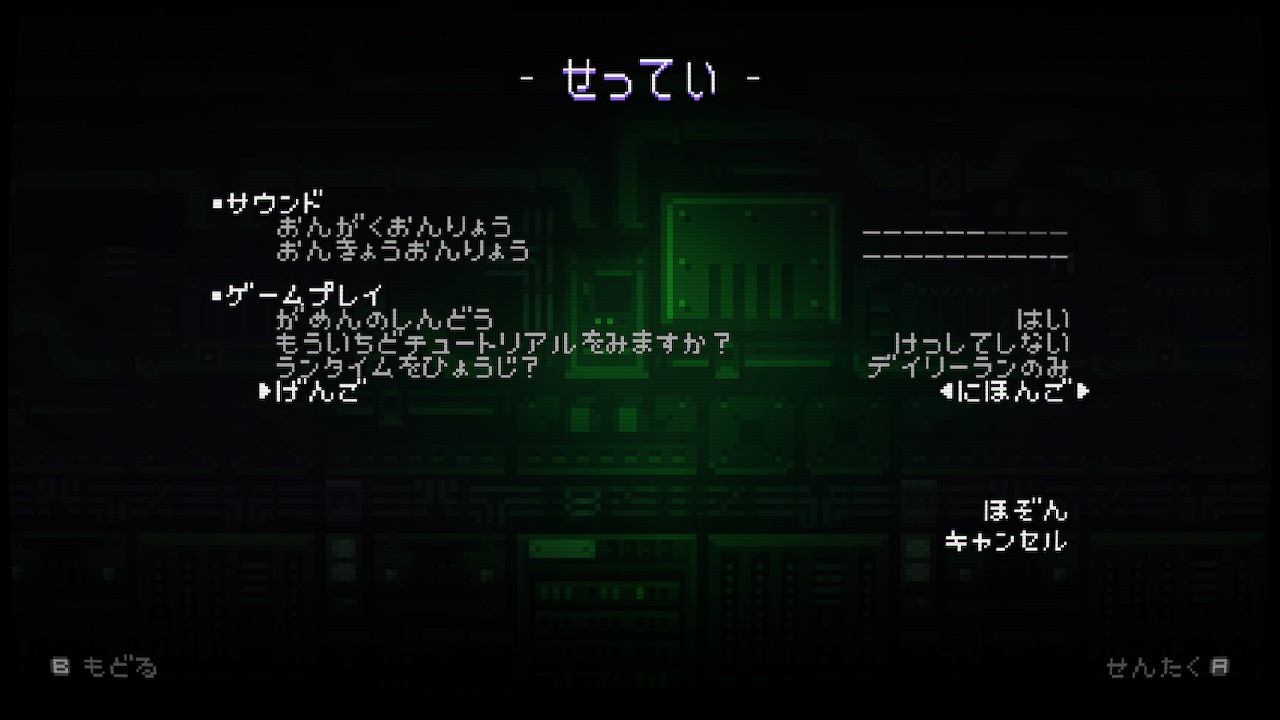

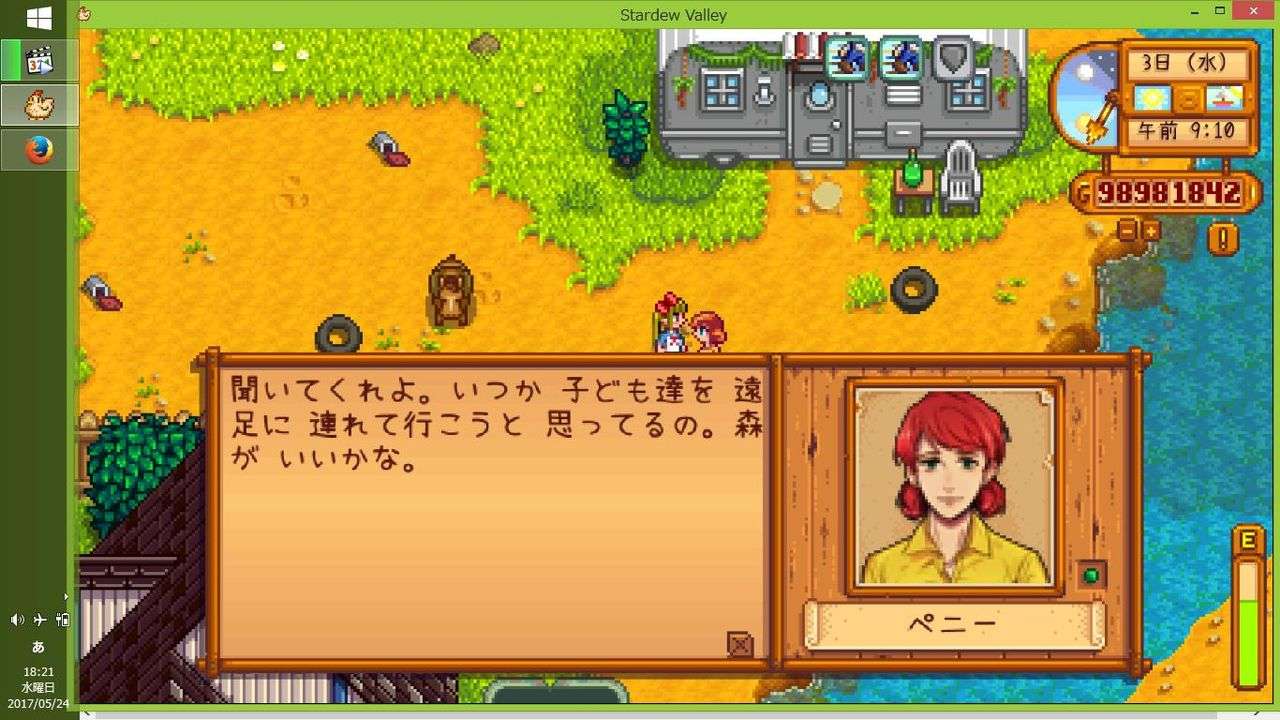

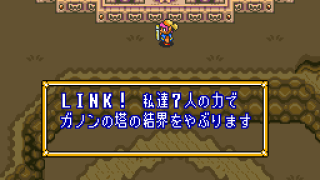

Because of this long-lived connection between video games and English, Japanese gamers expect a certain level of English in their games. So when a game features no English at all, it feels very weird and awkward. This expectation or acceptance of English especially applies to menus, messages to the players, and other user interface text.

Western games are characterized by this "must translate everything" assumption. As such, weird-sounding text and Western games go hand-in-hand the same way old retro games and bad English go hand-in-hand

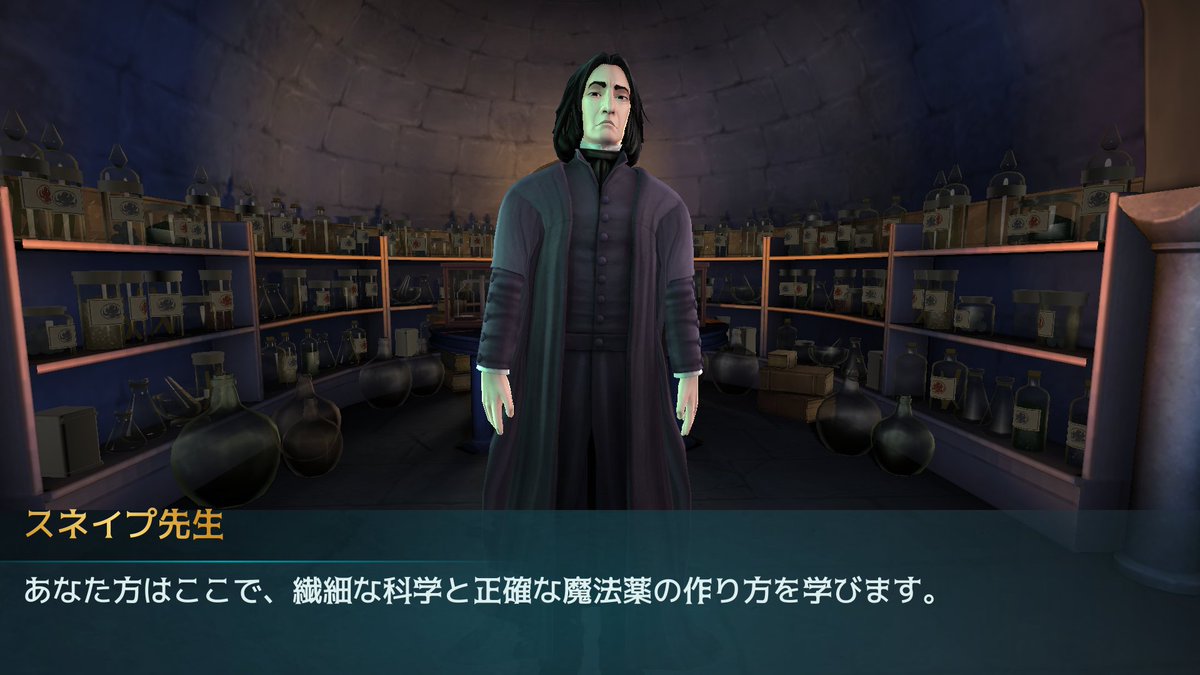

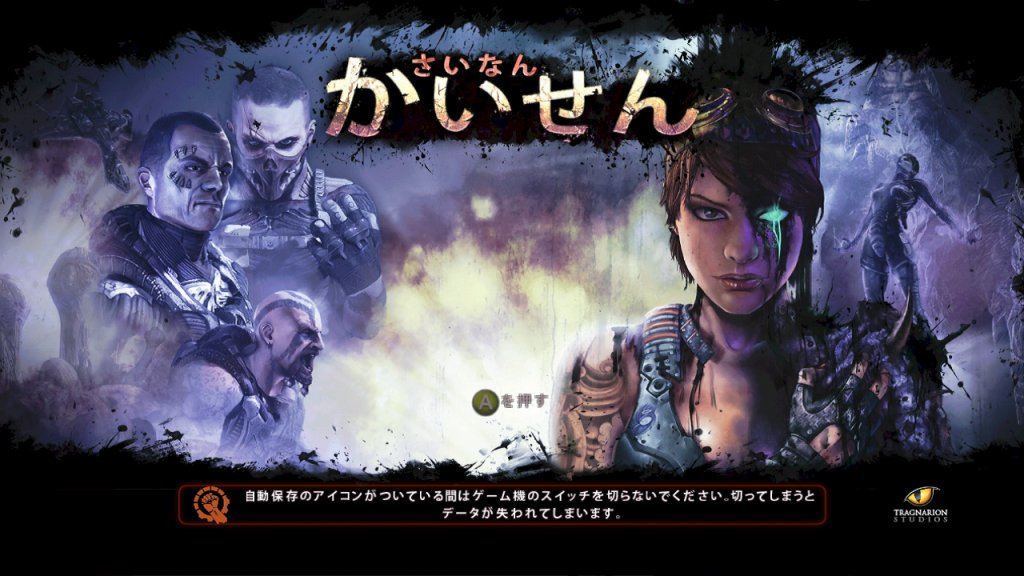

If you’re not familiar with how Japanese works, the two examples above might not seem out of place. But keep in mind that Japanese games regularly look like this:

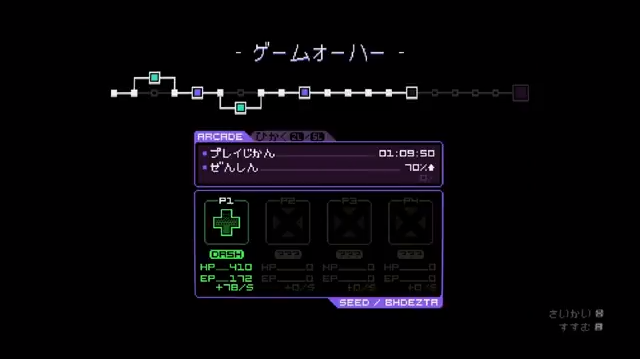

Common Problem #2: Translating EVERYTHING to the Extreme

This is kind of similar to Problem #1 but not exactly the same. If you’ve ever listened to Japanese video game voice acting or listened to Japanese anime, you’ve probably heard characters shout words in sort of garbled English when doing special moves. Here’s an example:

Basically, the lady in the voice clip shouts magic spell names using phonetic English. The developers could’ve easily used the Japanese words for “Fire Bolt”, “Eruption”, “Explode”, “Wind Blade”, and “Thunderbolt”. But they didn’t, because:

- The game and character don’t really have any strong connections to Japanese culture

- It sounds cooler and more exotic to Japanese players this way

- Using not-fully-translated phonetic English like this is normal and often expected in Japanese entertainment

So if you end up turning every special term into fully-translated Japanese, the result is likely to feel cheap and awkward.

Here’s a silly online comment about this phenomenon, in fact:

I’m not sure which game it’s talking about, but it’s probably referring to Hearthstone:

|  |

| "Flash Heal" in English | shunkan kaifuku in Japanese |

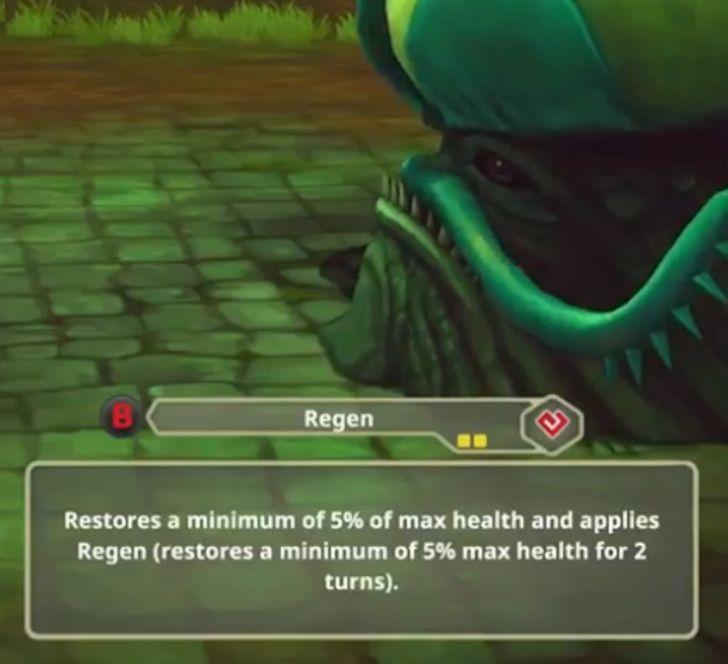

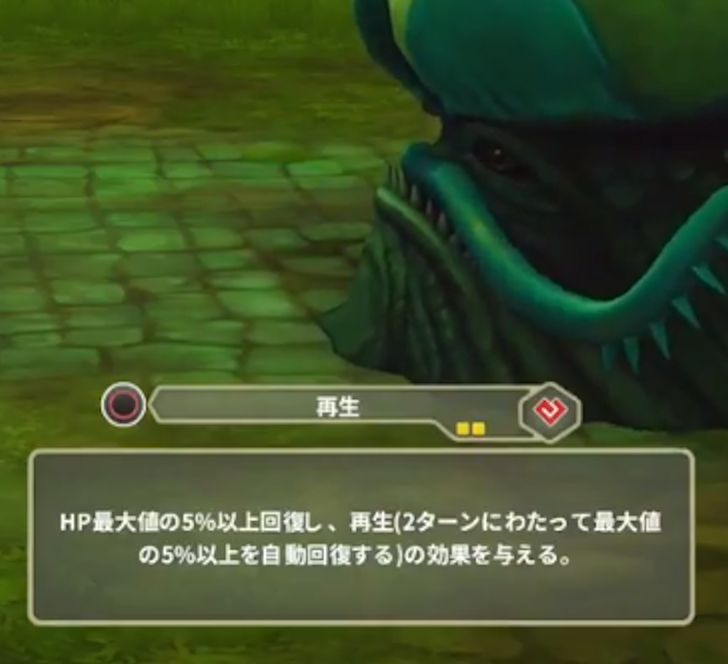

Another example is Earthlock, which is often compared to Final Fantasy IX and is a love letter to the JRPG genre. Unfortunately, the translators never really took this into account, so all of the phonetic English you’d normally see in Japanese Final Fantasy games was fully translated out. Even basic terms like “Cure” and “Regen” get this treatment:

|  |

| "Regen" is a common term in these sorts of games and is often left in phonetic English | But the Japanese version ignores historical precedence and translates it out |

Problem #1 and Problem #2 don’t make or break game translations into Japanese, but they can definitely hurt the overall experience. You can easily avoid them if you and your translator have an open line of communication. These next issues can turn your hard work into a laughingstock, however.

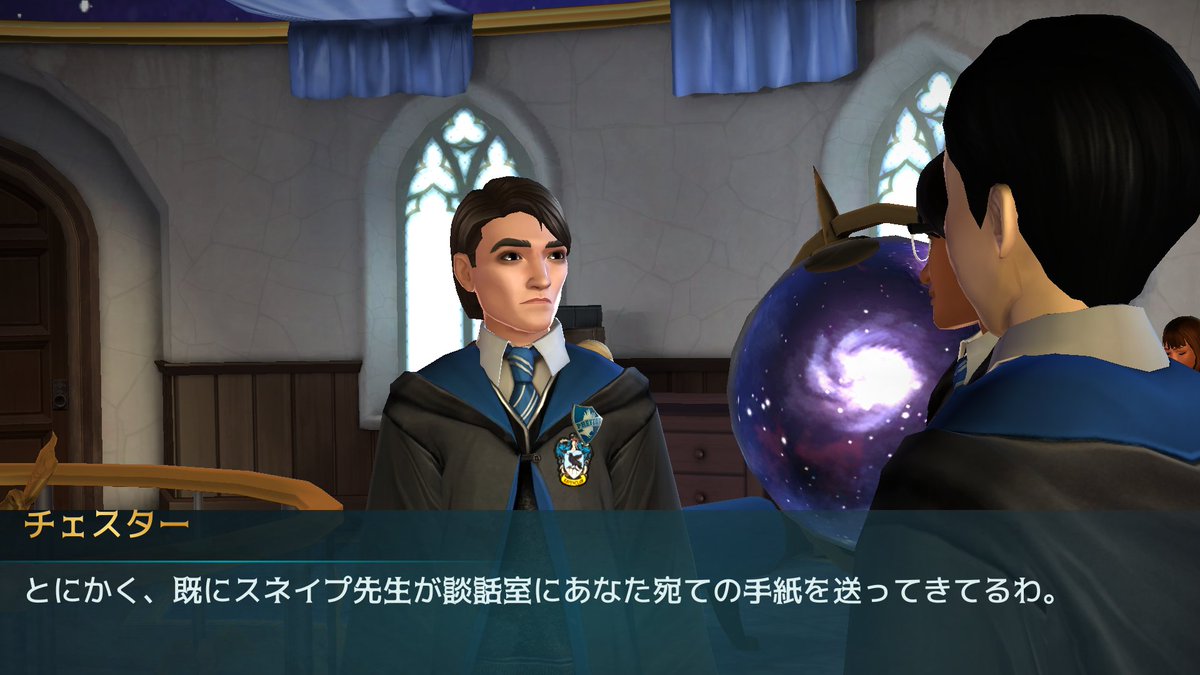

Common Problem #3: Speech Styles

The Japanese language has some qualities to it that aren’t as clear-cut in English, particularly when it comes to entertainment. Different genders use different speech styles, characters of different ages use different speech patterns, the language has multiple politeness levels that depend on the relationship between the listener and the speaker, some occupations use stereotypically different language, etc.

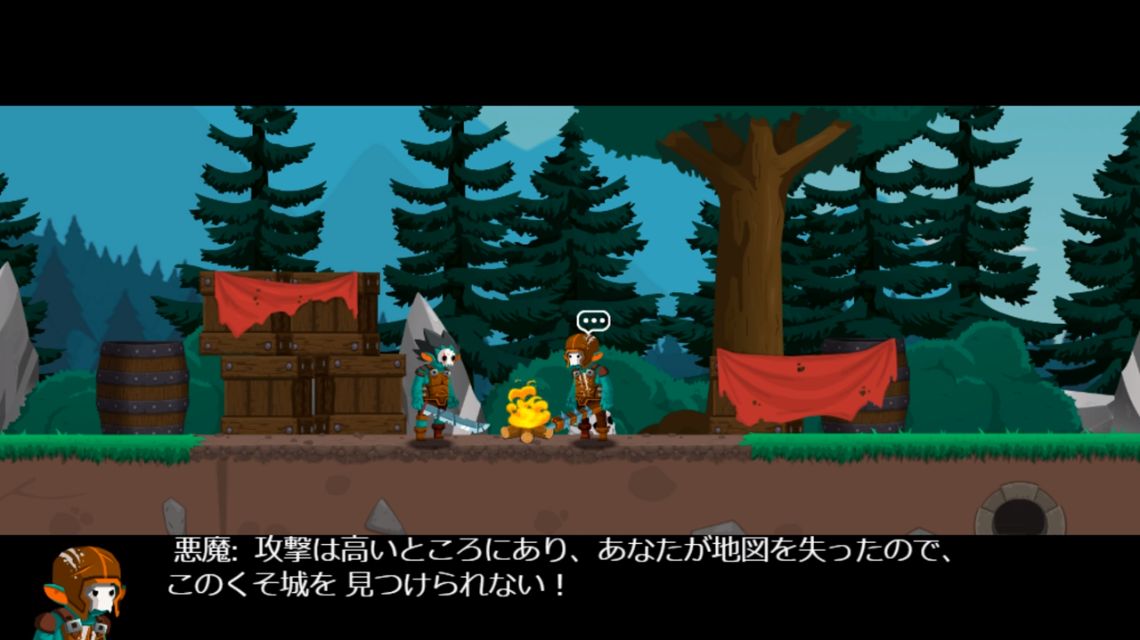

All of these things quickly add up, so if you hire a stranger to translate a giant text file of dialogue into Japanese, the result is probably going to be very bad unless you provide lots of extra notes, screenshots, videos, and back-and-forth communication. Otherwise you get moms talking like demons, tough guys talking like little girls, etc.

(source)

There is a sort of “neutral” Japanese, but it still comes across as polite-yet-sterile.

Common Problem #4: Blindly Trusting the Accuracy

Imagine you’re a game dev and you’ve just finished a game. You want to release it in Japan to get even more sales, but you don’t know Japanese. So what do you do?

You’d probably try to think of a friend or someone you know who could help, right? And then after that you might look around online for translation companies. Eventually, you get your game script translated and everything seems to be okay.

But if you don’t know the language to begin with, how do you know the translation is accurate? This is precisely how things like “All Your Base” and Vroom in the Night Sky get made!

(source)

(source)

The problem is that game translation is very different from ordinary document translation, so if you simply send off your text to get translated, wait a while, and then get the finished translation sent back to you, you’re probably in trouble. Even more so if you use an all-in-one agency that talks about translating into a hundred languages and handling a wide range of materials.

Also, a good game translator will probably ask lots of questions about context – maybe so many questions that it gets annoying sometimes. If there’s very little communication, then you can expect a lousy translation.

Heck, I’ll even skim through it for you if there isn’t much text – I actually check/document lots of translations on the side now that Legends of Localization is my main job. I might even do it for free if it’s super-short and/or you’ll let me do an article about it 😛

Summary

More than anything, though, the quality of the Japanese translation (and any translation) ultimately falls to the developer. If you provide lots of notes about context, lots of info about how different characters should behave, lots of screenshots and videos of key moments, and just be there to answer lots of questions, the translation will end up pretty good. But if you just hand a bunch of text files to a random company that doesn’t specialize in game localization, then you are on the way to destruction and have no chance to survive make your time.

If you liked this brief look at how game translations into Japanese can mess up, you'll like this article about popular and infamous Japanese translations too!

Is that problem with Celeste’s translation an actual, genuine mistake? Would any native Japanese translator come up with that line?

My guess is that it was handled by a reverse-auction translator who agreed to translate it for the lowest price but didn’t really know what they were doing.

The developers said the translators were recommended to them by a separate party.

That’s not the same thing as a reverse auction. A reverse auction is literally a type of auction, whereubout instead of the selling goods, the buyer’s selling an agreement to buy them.

Cool, thanks!

It’s entirely possible that the recommended translation company doesn’t handle all languages and so sub-contracts out the ones they don’t handle in-house.

You see that especially with the companies that claim to translate EVERY LANGUAGE. They don’t. Of course. They just hire a contractor translator when they need one.

My first encounter with 気ちがい (lunatic) was the legendary shit-tier anime known as Chargeman Ken. It’s a children’s superhero cartoon, but the characters and their motives are so sociopathic it’s really funny, and they sure like to use that term. Some quotes with it even acquired meme status in the japanese internet.

I think translating “I had a crazy dream” using “psycho madman” instead of “crazy” at least counts as a translation mistake, even without considering yet the implications of including it in an all-ages game.

Hopefully the social media lets the original developers catch a break for this since they were completely blindsided by this.

Basically, this whole fuss is an issue because some leftists who want to turn Japan into North Korea got together, organized, and went into full language police mode. There’s nothing actually wrong with the word. It was used completely normally until the mid 70s, and in fact still is used that way today by people colloquially and in doujin works that aren’t published by any mainstream media company, but in the 70s leftist organizations made an uproar and the until then innocuous word was reclassified as wrongspeak, based on the argument that it’s discriminatory against mental health patients. Yet, as I said, it was and is still used in exactly the same fashion as maniac or crazy in English. For example, a baseball enthusiast could be called yakyuu-kichigai or yakyuu-kichi, just like Hulk Hogan fan’s enthusiastic fans were called Hulkamaniacs. A crazy idea could be called kichigai-jimita hassou. However, nowadays, in mainstream Japanese media, the word is taboo, bleeped out when people use it on the air, and even wiped out from old works when they are republished, and so on. That’s more of a symptom of leftist insanity consuming Japan than anything else.

For example, that exact phrase 気違いじみた夢 for “crazy dream” or perhaps “insane dream” is used right here in this book which was translated into Japanese by a native speaker.

まるでこのすべてが気違いじみた夢みたいに感じられた。

maru de kono subete ga kichigai-jimita yume mitai ni kanjirareta.

Rough reverse translation (book was originally in English) translation: “It all felt as if it were a crazy dream.”

So yeah, it’s not even a translation mistake. It’s just a word that ruffles the feathers of Japanese Marxists.

Source here:

https://books.google.com/books?id=7SZKCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT8&lpg=PT8&dq=%22%E6%B0%97%E9%81%95%E3%81%84%E3%81%98%E3%81%BF%E3%81%9F%E5%A4%A2%22&source=bl&ots=Kba_BfptSD&sig=GN8vluLDJEWBRyk3SLLmTHHo9Do&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi0vMmdrJDeAhWud98KHRD5CNkQ6AEwAHoECAkQAQ#v=snippet&q=%E6%B0%97%E9%81%95%E3%81%84%E3%81%98%E3%81%BF%E3%81%9F%E5%A4%A2&f=false

“Japanese Marxists”? You’re attempting to describe something that was widely discussed among Japanese video game players with an air of disbelief that the translation could have gotten things so very, very wrong in meaning and tone.

At this point, you sound like you’re going pretty far off the deep end yourself. I hope you’re okay.

The 70s? That’s almost half a century ago!

It’s pretty normal for words to change meaning and subtext. There are plenty of English slurs that are based on words that were used normally long ago.

(Some English commentary on the translation gaff say the word could be translated to English as “retarded lunatic”, if so, there’s an example of some slurs that would have been considered clinically correct as recently as the 1950s. No Marxist conspiracy required.)

Here’s an example from 2010 of a synonym for “crazy” being censored:

https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2010-06-28/battle-angel-alita/last-order-manga-put-on-hiatus

What an anachronistic idea you have of how this occurred. You’d get some funny looks from people of all ages and walks of life in Japan if you tried to sell your largely imagined version of events.

“leftist insanity consuming Japan”

I hate to necro a year old comment, but are you sure this is the same Japan we all know of?

Considering how Japan was completely dominated by a right-wing, anti-leftist government at the time described (and for many years before and after that), I guess it’s possible the guy describing that government’s actions as “Marxist” hadn’t yet realized he’d journeyed here from some alternate universe with a completely different history from ours.

Even the link in the Celeste article doesn’t say what the word was. Can someone give us some context?

I don’t have a good article handy but it’s briefly listed here under “kichigai”: http://avery.morrow.name/blog/2012/04/things-you-cant-say-on-japanese-television/

How odd. Some of the words on that list that they claim are offensive to foreigners aren’t offensive at all. Like “Dutchman”? And they wouldn’t even use a guy’s name because it had some crude syllables in it? It’s the “Scunthorpe Problem” all over again!

“Dutchman” is a South African slur for white.

Huh. That’s funny, since it’s just “a Dutch man”. What happens when they have to cite the infamous ghost ship The Flying Dutchman?

Also how is “Indian” offensive? That’s just the term for a person from India. If they mean native Americans then it’s still used there in a neutral sense, albeit a historically and geographically inaccurate one.

I’d assume the entire point is just to avoid words that might potentially result in angry calls from offended foreign viewers, so there’s no real point in overcomplicating the matter by detailing what kind of foreigners might get offended by what word and in which possible contexts. If you just toss them all on a list of words you can’t say you never run the risk of messing up.

As far as Indian goes, I’m pretty sure it’s relatively minor compared to some other offensive racial terms, but it’s still met with disdain compared to Native American or First Nations. After all, that was the name they were given by the people who destroyed so much of their culture and civilization, then afterwards what they were referred to when the invaders’ descendants erased and muddled up what was left of their culture until the common knowledge of it barely resembled what it actually is. And it’s, like, derived from another nation that’s completely unrelated to them. There’s a lot of reason to hold the term in contempt.

But it generally isn’t though. I mean at least all the Indians I know call themselves that and not in a “reclaiming” way either.

Adamant has it pretty much dead to rights here. There’s no sense arguing about whether or not a term should be offensive; from a PR perspective, it’s absolutely vital to avoid giving the PC Police any ammunition. Unless the entire purpose of your project is to make a statement against political correctness, you’re best off learning all the relevant taboos and avoiding them.

I think it varies a great deal depending on where one lives. In the United States, it seems to be relatively common to use the term Indian to describe a Native person. Here in Canada, I never hear it. It’s so uncommon, I don’t even know if it is considered to be offensive or not.

When I hear the word Indian, I always think of the country first. This has caused me some confusion a few times in American media, actually. Luckily, the context always clears things up eventually.

‘Dutchman’ used to be semi-popular as a slur with the English, or in parts of the US for any caucasian foreigner who couldn’t speak English. It’s also used in a slur sense for South African Afrikaners, even recently.

I agree, it’s no f-bomb, but these things are never logical in any country. Japanese corporations abhor conflict, so better safe than sorry. There was an incident recently where a children’s manga artist drew a penis on the forehead of Ghengis Khan, who was one of the worst mass murderers and rapists in history – pretty safe, right? Nope, it pissed off the Mongolians, so the Japanese groveled and apologized and pulled it.

Wasn’t he NOT a rapist and that’s one of the reasons his realms were so unified, because he had strict punishments for crimes like that?

It’s funny that Japanese media would be so concerned what foreigners think when they’ve got such issues with foreigners in society.

“foreigners” yeah, no, there’s actually people of Mongolian heritage who live in Japan, they’re the ones who were “upset”, try again.

From what I understand anyone not of pure Japanese heritage can be considered a “foreigner” regardless of their actual citizenship status. Obviously, there are different schools of thought on this, and this is probably one of the more radical ones. It’s like white Americans who treat anyone non-white as if they just crossed the border regardless of how long they’ve lived here. But it does exist, AFAIK.

oh man, context is incredibly important, and probably the one thing that can cause issues in localization.

on the subject of problems #1 and #2 it always kinda baffled me what terms will and won’t get translated into Japanese. even outside the context of localization, what games I’ve tried playing in Japanese seem to be inconsistent (disclaimer: I’m not a native Japanese speaker, or even fluent, so I can’t speak from that perspective).

Yeah, lack of context can lead to some silly mistakes.

One particular example was Suikoden Tierkreis’ French translation. I don’t know how it was handled, but when you encounter old perseons, they were called “man/woman of Aged, instead of “aged man/woman” (well “homme/femme âgée”).

There is no country called “Aged” in this world, but it’s a mistake you encounter early on, so you can’t spot it immediately.

That sounds more like poor wording by a non-native speaker than lack of context.

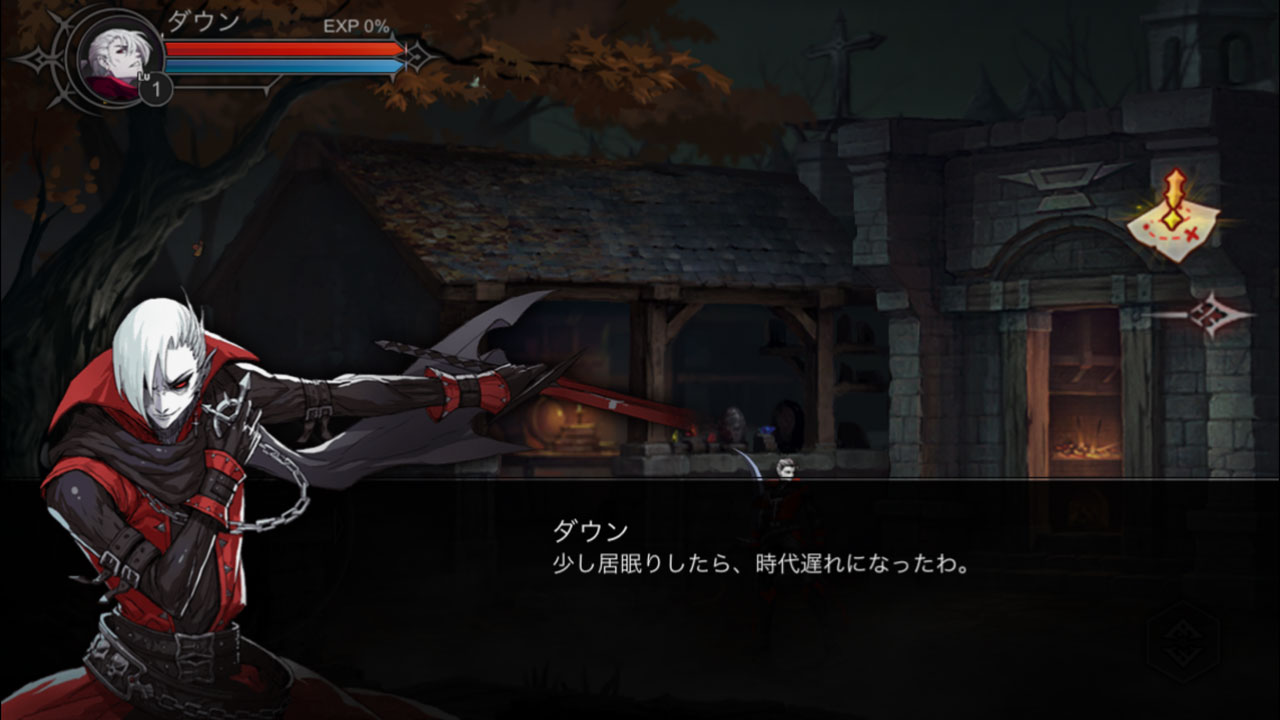

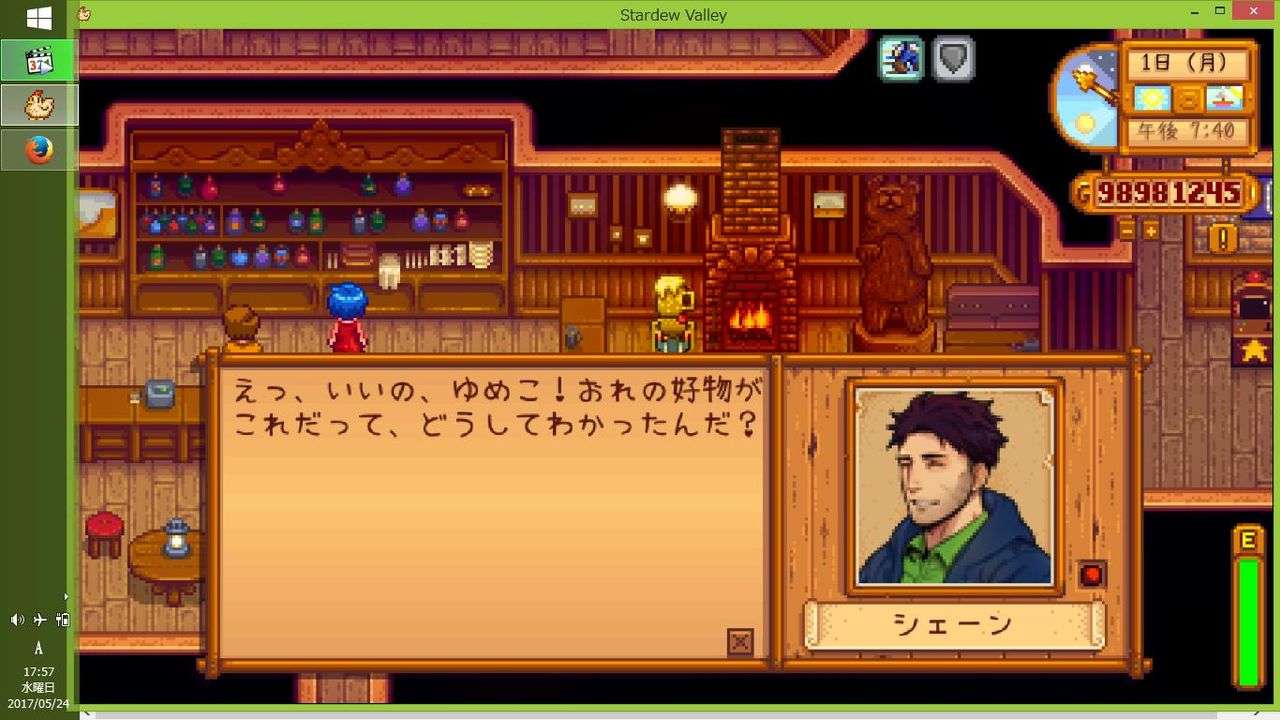

It bums me out a bit to see that the Stardew Valley translation isn’t that good. The creator of the Ranch Story/Harvest Moon/Story of Seasons franchise himself has expressed approval of the game, and Japanese fans seem to really be enjoying it, so it’s disappointing that their experience has to be tainted by a bad translation.

I can only imagine how Elliot’s dialogue was handled in the Japanese version! (For those who haven’t played the game, Elliot is a writer character. He has an especially flowery way of speaking that relies on a lot of metaphors and big words. Seems like a translation minefield…)

Given the quality of the English translations of Harvest Moon, it’s only fair. 😉

Touche. Now they know what we’ve gone through all these years! 😛

Spells in JRPGs do tend to use English words because, as you said, it sounds exotic to the Japanese. That’s nothing new, and I’m sure the spells would sound bland in kanji. And thank you for providing voice clips for a few of Celine’s spells. I’d been kind of curious as to what she sounded like in the PS1 version voiced by Yuki Kaida.

This article certainly does make one thing clear: if you’re going to be a professional translator, take it seriously.

Lovely article, the part about calling for context is so important xD So that’s a great indicator!

Also I had no idea you shifted to the site full time! That explains a lot about uploads. I’m glad you get to do something so fun full time!

Problem #1 reminded me of the Ganbare Goemon games, where common English game terms are rewritten in Japanese all over the place. For example, instead of 1 Player / 2 Players on the main menu, there’s ひとりであそぶ and ふたりであそぶ . Instead of TIME it says じかん and STAGE 1 is written as すてえじ一

Of course, the creators did this intentionally as a parody of the Edo period setting, and going with the anachronistic humor of the games. But when a game translation does this, it’ll unintentionally look very silly and out-of-place.

I think Getsu Fuumaden was another Konami game with a minimal amount of English due to the distinctly Japanese setting… although the game has a far darker tone than the Goemon series.

The idea of gamers who criticize a game for having too much of their native language simply baffles me.

Quite a lot of Norwegian gamers have an instinctive feeling of disgust if we boot up a game and it’s in Norwegian. Even if the translation is otherwise spot-on.

That’s more because it feels patronizing than anything, and can also give the impression that the game is made for kindergarten-aged children. But yeah, I guess it’s kind of comparable in that it screams “whoever localized this is extremely unfamiliar with what the market wants an end product to look like”.

While I was reading this article, I was thinking something similar: if a game is entirely in Japanese, it’s probably for young children who haven’t learned any English words yet.

Since I wrote this, I remembered that Final Fantasy IV Easy Type uses less English words.

I guess that’s kind of comparable.

But yeah, the situation is basically this:

Just like video games in Japan have always featured a decent amount of English in menus and the like, video games in Norway have always just been left in English, so in both cases, this is what the audience expects. The only games that HAVE traditionally been translated into Norwegian are educational games for toddlers and kindergarteners, so whenever some misguided publisher decides to translate a game for an audience over the age of 7 into Norwegian (a choice most definitely not based on market research, since market research would’ve told them to not do that) they’re not only wasting money giving the audience something they didn’t ask for and have no interest in, the audience also feels like they’re being treated like little kids that can’t read English.

It’s all pretty similar to the situations Mato describe in the article, where games get translated into Japanese by companies that have no experience with the Japanese video game market and miss the boat really bad on what that market expects in a local release.

Kindergarten-aged children can’t read kanji at all, so I highly doubt that in general.

The only games I can think of that are translated into Norweigan are published by EA. Does each European publisher have its own group of languages that it translates games into? (eg: Nintendo of Europe has French, German, Spanish, Italian, and sometimes English if they don’t keep the American translation.)

Like many business choices, it’s based on market research, and, as that kind of thing tends to be a trade secret, each publisher gets a slightly different answer from their own different study so they choose different language set. How many speakers each language has is decently public information, but how many paying customers will only buy it if it’s translated to their main language is a whole different beast. Not to mention the different demographics within video game players (Pokemon vs. Abe Lincoln Teaches Killing).

Apparently this really differs from country to country. I agree with Kakahan44, and it seems silly to expect things to remain in English in a translation – here in the French speaking world if something is translated then we except everything to be translated and it would look silly/unprofessional if something were left in English. I have a hard time understanding why a Norwegian or Japanese player playing a translated game would be annoyed that something is translated.

That being said, I can sort of understand this if you grew up with something always being in English. For instance I am playing a fan-translation of Mega Man Battle network, and I find it disturbing that the chip names are translated – because I grew up and played with the English names so much it seems weird to me they’re renamed. So I can guess Japanese and Norwegian players have this awkwards feeling like, “why did they affect this”.

We Indonesian has some problem with that. This especially bothers older or longtime Indonesian gamers but not the newer (mostly mobile only) gamers. The reason for this is probably how for more than 20 years of gaming, Indonesian language was never included into the games. This lead to gamers actually prefer English menu in games. In fact, many hardcore Indonesian gamers I’ve met credited their fluency in English to their longtime gaming habit because of this.

It also doesn’t help that a lot of mobile game developers decided to translate everything into Indonesian eventhough it ended up to sound awkward or unusual to native speakers. In addition, native Indonesian usually use butchered, slangs, or non-official words 99% of their daily life (outside of formal stuff) (even in the working situations). This leads to how translation using the correct translation could sound ‘too rigid’ and ‘awkward’ eventhough technically and grammatically it is correct Indonesian. As a side note, we often appropriate words from foreign language and use it as it is thus make it even more awkward to hear some translation.

One example is ‘Settings’ menu. The correct Indonesian translation is ‘Pengaturan’ which is what everyone use in their games. It is not wrong, but it sounded a bit awkward to longtime gamers since the world ‘setting’ is already blended in unofficially into Indonesian language even for daily life and not just game. For example ‘setting up PC’ is usually said as ‘nge-set up PC’ which is a normal yet wrong way to say ‘men-set up PC’ which in turn is still not a proper Indonesian. ‘Changing the settings’ also said as ‘ngubah setting’ (‘ngubah’ is a wrong way to say ‘merubah’ which means ‘changing’, but ‘ngubah’ is used more often for daily stuff). The phrase ‘ngatur setting-an’ is also found often which literally translated to ‘setting the settings’. Well, I’m exaggerating for the last one. It actually more correctly translated as ‘changing to the appropriate setting’.

20 years, even more, of living with that makes us seeing the word ‘pengaturan’ as weird. This leads to many gamers aged mid-20 upward to still use English language even when there’s Indonesian language available (even if the translation is great).

PS: I’ve seen some local developers use incorrect but common Indonesian language to avoid the ‘awkwardness’ and ‘rigidness’ of the correct Indonesian.

It’s really interesting but it’s the same way in Denmark and it really seem to be the same case here!

Problem 1 is interesting, because when localizing the first Crash Bandicoot game, they were told by the Japanese people handling it to translate absolutely everything. Even they noticed that Japanese games had much more English text than that. But, those localizations also had a habit of adding in a lot of unnecessary, useless features, so maybe the Japanese side was someone trying too hard to justify his job.

In the Japanese translation of Spyro the Dragon, all of the level names are in English, though not necessarily the same as the original.

What are these “singular/plural issues”? I’m interested. Also, please could you explain the problems in the last screenshot?

The first thing that comes to mind when I think about translations that aren’t wrong, just odd, is the English translation of a German book called Dragon Rider, where magical beings are called “fabulous creatures”. It just sounds silly.

Some languages don’t have any morphological features to indicate plural. Some languages use the same word for the singular and plural version of a noun. Without context and without any notes from the developers, sometimes there is just *no* way to know for sure what was meant. Translation can feel like gambling in these cases.

I know. I’ve just never heard of issues with plurals when translating into Japanese, a language that sort-of-kind-of-ish-maybe doesn’t have them.

plurals in Japanese are more contextual, like if you use a plural it’s because you’re referring to a specific set of more than one of a thing. this is in contrast with a lot of Indo-European languages where plurals are compulsory in certain cases.

like in English I would have to say “I like dogs” since there’s more than one dog in existance. in Japanese you would just say “inu ga suki”. in English “dogs” explicitly means multiple dogs, but in Japanese “inu” is just ambiguous about the number of dogs; it’s neither singular nor plural. however, if I said “inu-tachi ga suki” this not only means more than one dog is involved, but I’m talking about a set of dogs that I like (similarly I might say “kono inu ga suki” if I’m taking about a specific single dog, but don’t quote me on that). going from English to Japanese could have issues stemming from whether or not an English plural is referring to a set of nouns (“these dogs”) or an indefinite number of dogs.

I remember in a Japanese linguistics class I took the professor brought up a study or class done with native English and Japanese speakers. both groups were asked to draw “banana” (or “バナナ”), and while all the English speakers drew a single banana, most of the Japanese speakers drew a bunch of bananas.

Even for non-speakers this can be observed with several Japanese to English loanwords which have the same singular and plural like “samurai”, “ronin”, and “ninja” (though both it and “ninjas” are considered valid in English). Exceptions, like “katanas”, do exist though.

A big one that comes up is “you” – in English it can be singular or plural but if the context isn’t clear the translator could choose the wrong one.

As a sorta crappy not actually real example, the line “You hafta eat the bombs!” could end up sounding the same in Japanese and not make it immediately clear there are multiple bombs to eat, so a player could end up eating a well-hidden one and then wonder why the timer is still counting down.

I, uh, really need to start documenting translation problems into Japanese too, haha

I can think of a possible solution: use nan-bakudan or suu-bakudan. I’m sure that someone fluent in Japanese can give a better example. Then again, I guess a translator can forget that simply “bakudan” can confuse people.

On the topic of translation mistakes, I wonder if there was ever a book where a character offhandedly mentioned their “brother” and the translator used the word “aniki”, only for a later book to reveal that the brother is YOUNGER. Just something I’ve been thinking about.

If I remember correctly, Ubisoft was the first big name to consistently translate into Norwegian. Lots of other publishers translate the UI, but leave in-game text alone. In the beginning it was pretty bad, too. The most infamous example being the “Interact” button prompt, for which there is no good Norwegian translation. We ended up with a word that most commonly is used to mean “coordinate” (samhandle). I’m assuming there was no opportunities for contextual translation (“drive” for a car, “open” for a door, etc), so they had no good alternative options, but it was still a nightmare.

That reminds me how “Use” is a massively versatile word in English and it’s everywhere in video games. Need to see if “つかった” has any major differences.

I’ve heard some poor things about early Ubisoft’s translations into French (their native language). Supposedly several French versions of Might and Magic games couldn’t be completed because they never quite did the text parser for riddles right. Depending on the game either the parser still expects the English word, or it would require you enter the French word but it would require the accent marks but not let you type them. That and how they can seem to agree on their own name (At E3 you’ll see employees in the same presentation vary between “you-bee soft”, “oo-bee soft” and even their official Japanese name ユービーアイソフト or “you-bee-eye soft”.) make it really surprising they now have a reputation for decent Japanese translations.

https://jisho.org/search/tsukau

Here’s an entry from a dictionary. It seems to cover most of the major definitions of English “use”.

It’s kind of funny, because the same thing with translating english words, that should have been left alone, also happens usually happens the few times we get a Danish translation.

This is however because games aren’t usually translated to Danish, so people that play games are often used to the english terms, like saying “player 1-4” or “controller/joypad”

I think I remember reading an article about how when Hollywood movies are in “Japan/Tokyo,” you can tell if they shot on location or not because the Hollywood versions of Japan are usually filled with only Japanese on their buildings and signs when in reality there’s English all over the place. Interesting to hear that a similar mistake happens in game translations.

Basically, Japanese games would have menu labels and other incidental words in English right? These same stuff would then be translated anyway when it’s time for german, spanish etc. translations. Final Fantasy series for instance is a good example of this in action. And let’s be honest, those definitely would look awkward at best if they did have Kanji and Kana there. And as you surmised, Western developers would liberally litter their UI with Japanese just because they can.

It’s extremely difficult for me to grasp the idea of people looking down on games for having too many words in their native language. Maybe part of it is because English looks more exotic to native Japanese speakers, and therefore the lack of it implies it’s childish?

It’s because Japanese gamers know some English, and the only games that get fully translated are for children; it has nothing to do with how “exotic” English looks. It’s like if someone put a tooltip explaining how to start the game at the title screen when it already says “press start”.

“Basically, the lady in the voice clip shouts magic spell names using phonetic English. The developers could’ve easily used the Japanese words for “Fire Bolt”, “Eruption”, “Explode”, “Wind Blade”, and “Thunderbolt”.”

Where is this from? It sounds so familiar…

It’s from Star Ocean 2. Which reminds me, I oughta look into that game and write stuff about it, it’s such a translation disaster, haha.

are we just not gonna talk about handsome anime shane?

That reminds me of how in the Japanese translation of Slay the Spire, the Japanese translation refuses to use any English written out, though it uses words written out in Katakana extensively… even to the point where they’re too long, and don’t properly fit on the page.

How is the kichigai thing a slur? explain context plz? On JP dictionaries, it says it means mad lunatic or something

It’s more accurately translated as “retarded lunatic”.

What’s been on my mind for a long time is how even in somewhat competent J2E translations, or at least ones that aren’t outright broken, there are any number of turns of phrase one gets used to seeing that may be reasonably accurate, but still aren’t something a native English speaker would say in that situation. Think of how 許せない, さすが, あの人, or しようがない/仕方がない get handled. (Translations of 青春 have started to stick out for me too.) I’m wondering what the equivalent terms would be that stick out in mediocre E2J translation.

I think you should look into the delta rune chapter 2 translation for an article, it has some pretty glaring mistakes that make it confusing as heck.

What kinds of mistakes? The localization is handled by a company that in my understanding usually does Japanese-to-English more than the other way around, which is interesting.

Fun Fact : Some of Japanese games have one Spanish word, that is “Fin”, instead “The End”. Especially you have completed the game. For instance JRPG, or other games

That’s probably from the French version and is also somewhat common in English films