In 2018, I wrote an article about common problems when translating games into Japanese. Many game developers took notice and shared the article with others. A few even reached out to me for advice and consultation work, which I offered to do for free. They also agreed to let me write articles about their experiences.

With this new “Getting It Localized” article series, my goal is to shed light on actual things that have happened during actual game localizations, from the developer/publisher’s point of view. My hope is that these inside looks will help other developers avoid the same issues and improve the overall quality of their own localizations.

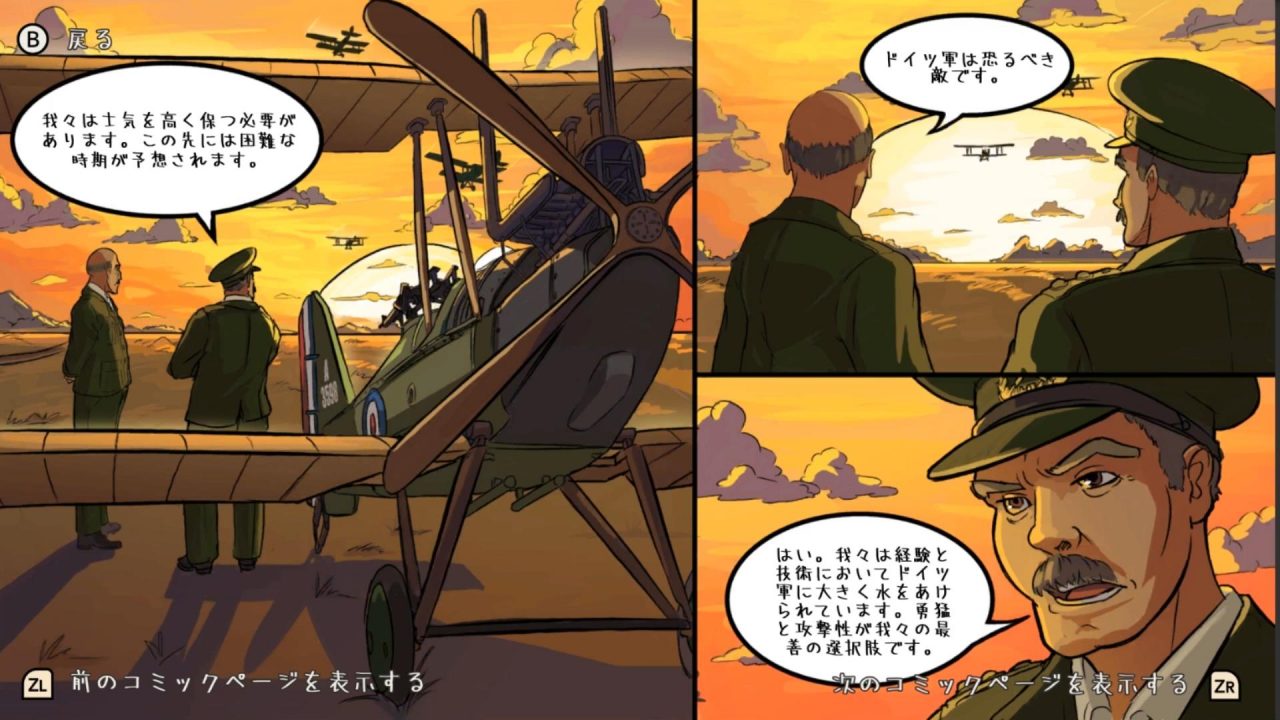

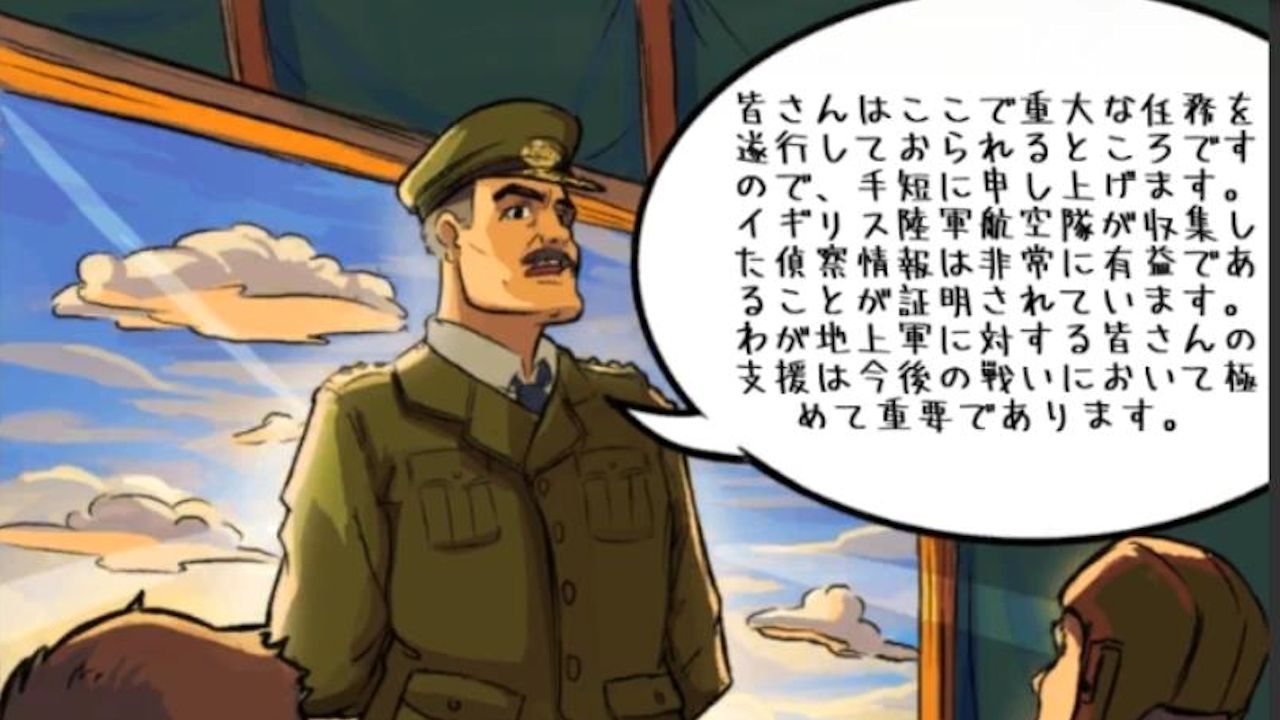

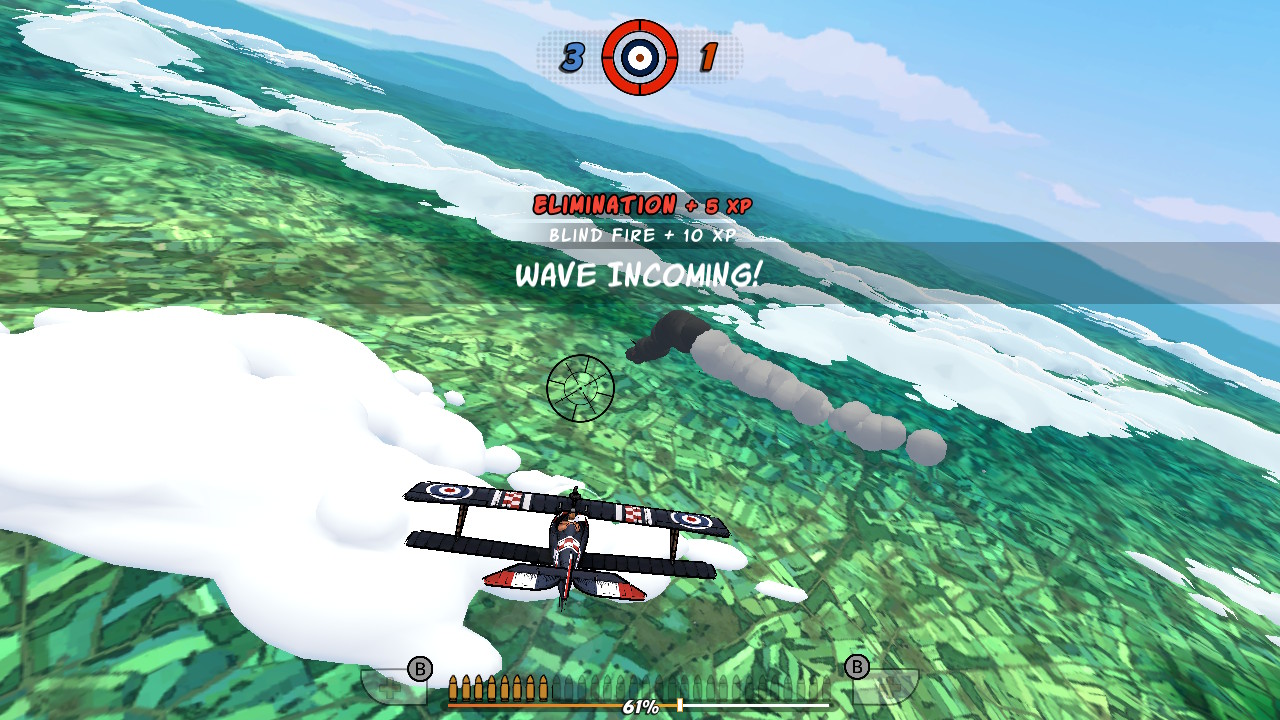

This time, we’ll be looking at Ace Academy: Skies of Fury DX and some specific problems that appeared during its localization into Japanese.

About the Game

In 2017, SEED Interactive released Skies of Fury, a World War I-themed airplane combat game. In 2018, the company released an upgraded version for the Nintendo Switch and called it Skies of Fury DX.

The game was originally only playable in English, but the new Nintendo platform inspired SEED Interactive to localize it into other languages, including Japanese:

We didn’t consider it (originally), as Play Store and AppStore are global, whereas Switch eShop is divided by territory (NA, EU, Japan) so it made sense to cover Japan separately.

For this article, we’ll be focusing only on the Japanese localization, as that’s why SEED Interactive contacted me in the first place.

First Steps

How do you even get a game localized into Japanese if you’re a small developer? Where do you start? Who do you turn to? Who’s good, and who’s not? There’s a lot of confusion at this point, and making one wrong decision here can make or break the final product.

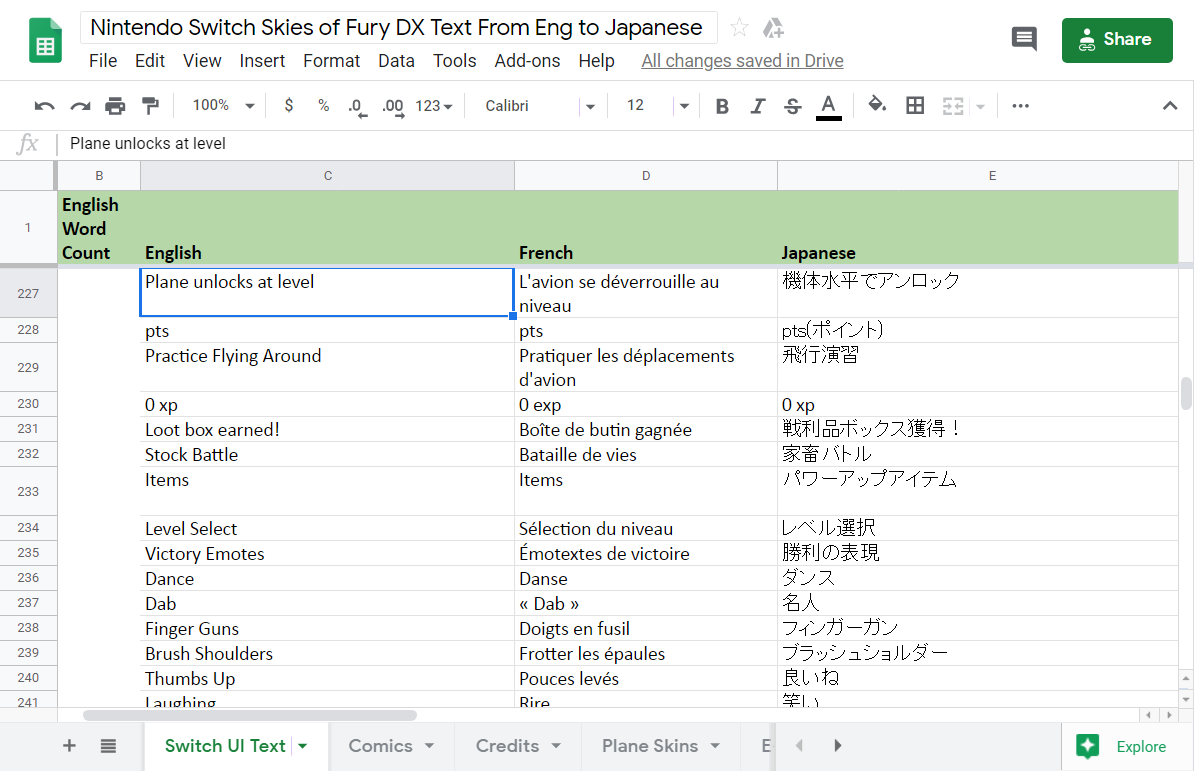

The process began with a partner company hiring a freelance English-to-Japanese translator to translate the game’s text, which was stored in a big spreadsheet. The translator submitted the finished translation some time later.

Checking the Translation

That’s when a producer at SEED contacted me and asked if I’d skim through the translated text to see if it was good or not. I agreed, but explained that I’m only a professional Japanese-to-English translator. I’m not formally trained in English-to-Japanese translation, so I usually don’t do English-to-Japanese work – after all, that’s how you get things like “all your base are belong to us” and “a winner is you”. So I only offered to check the basic quality of the text and provide some thoughts on it.

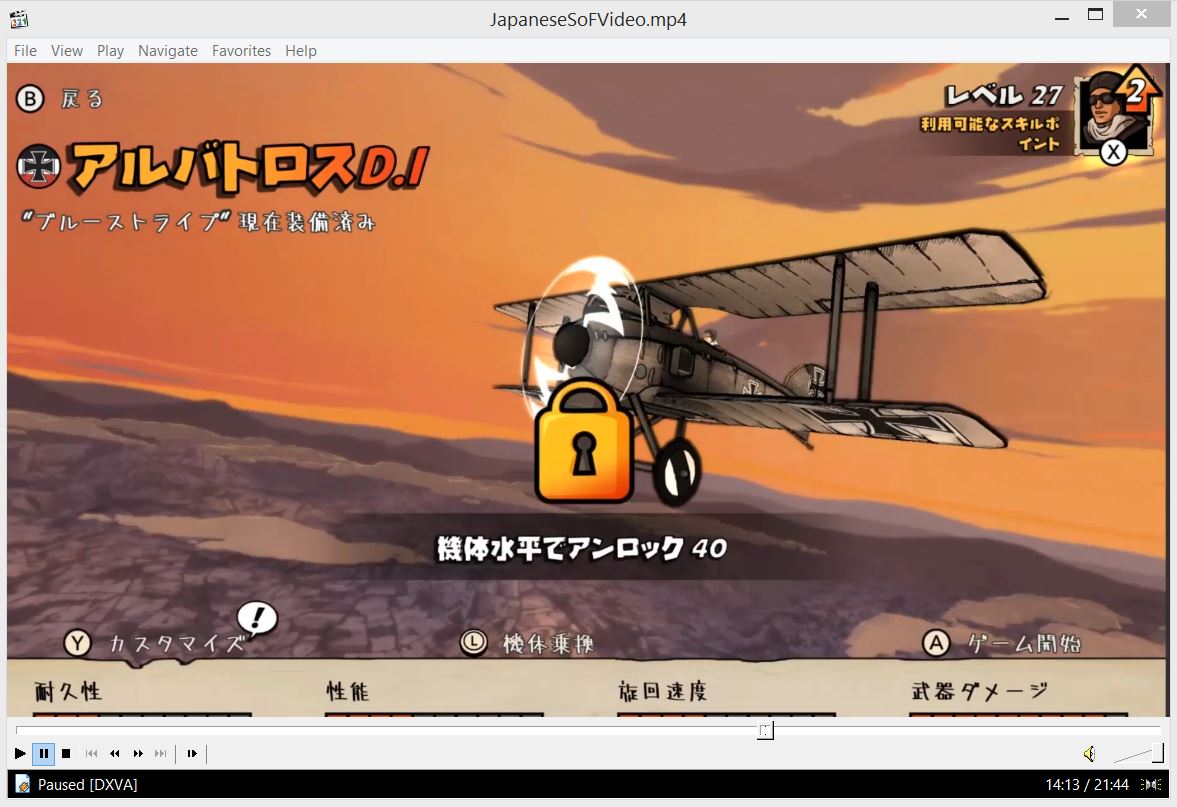

I also asked for context material, and the producer kindly provided a 22-minute video of the Japanese translation in action, as well as a free download code for the English game so I could see other things in action. I spotted many issues almost immediately.

Translation Notes

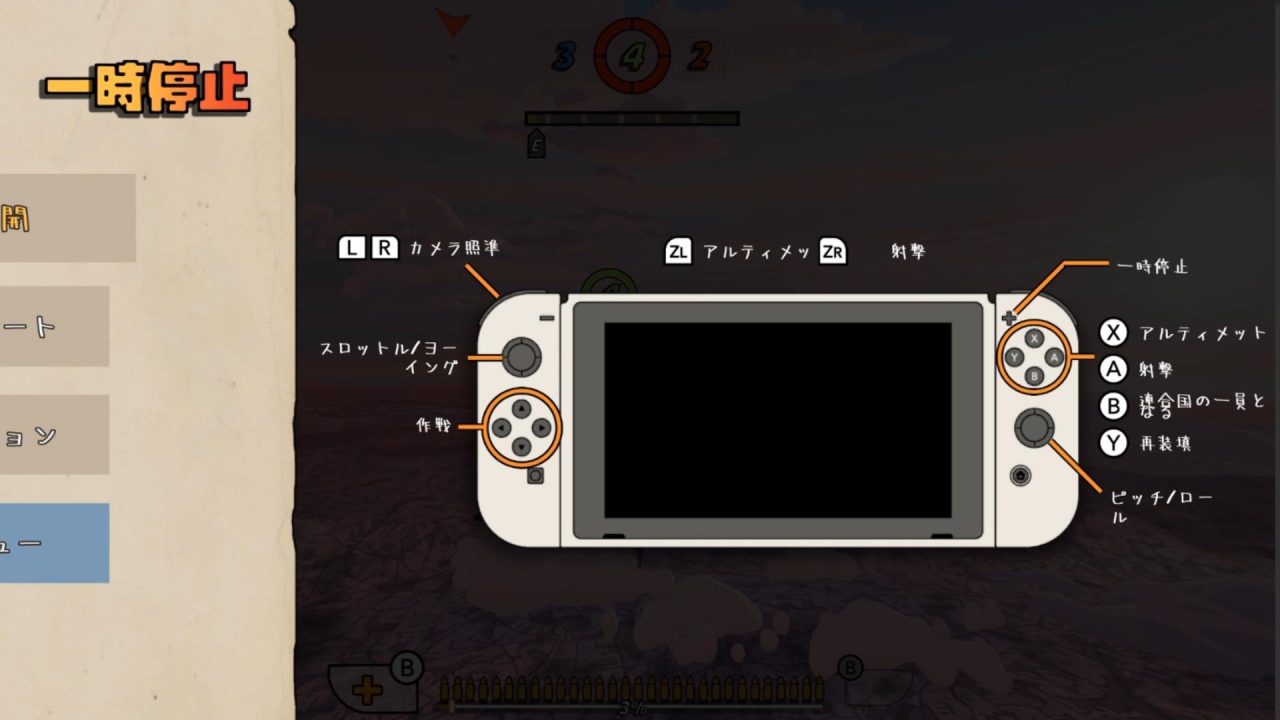

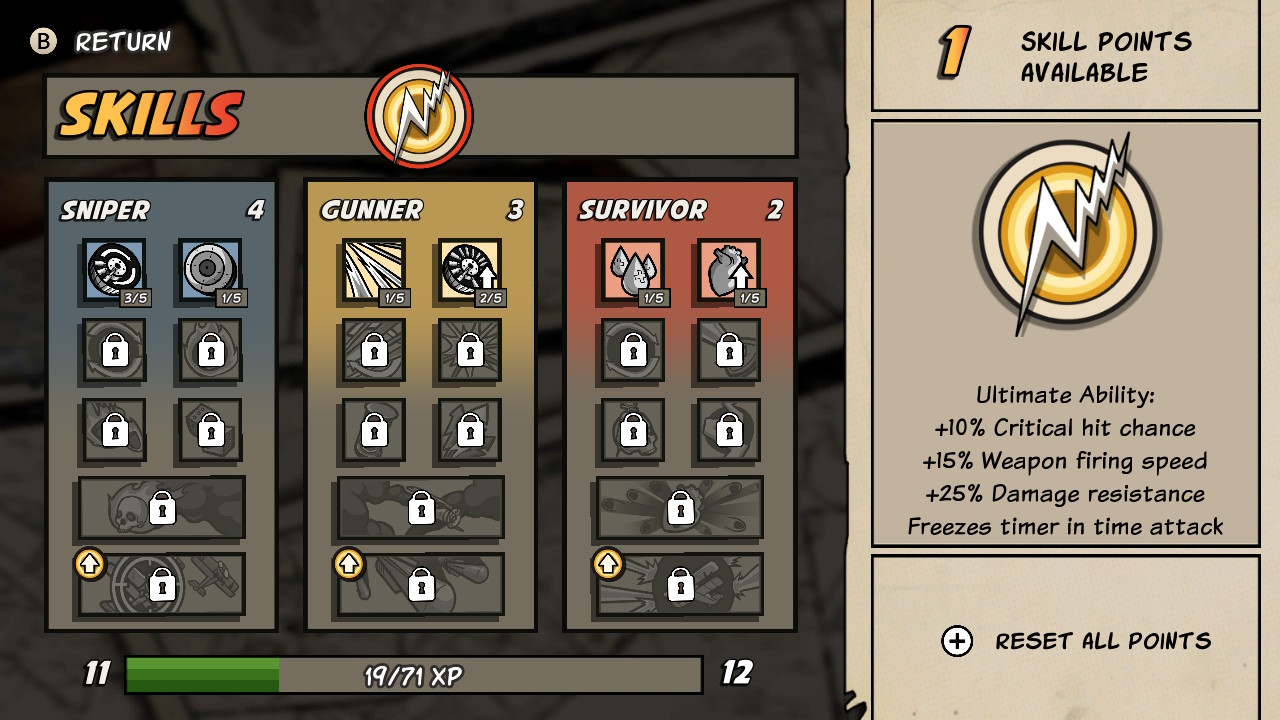

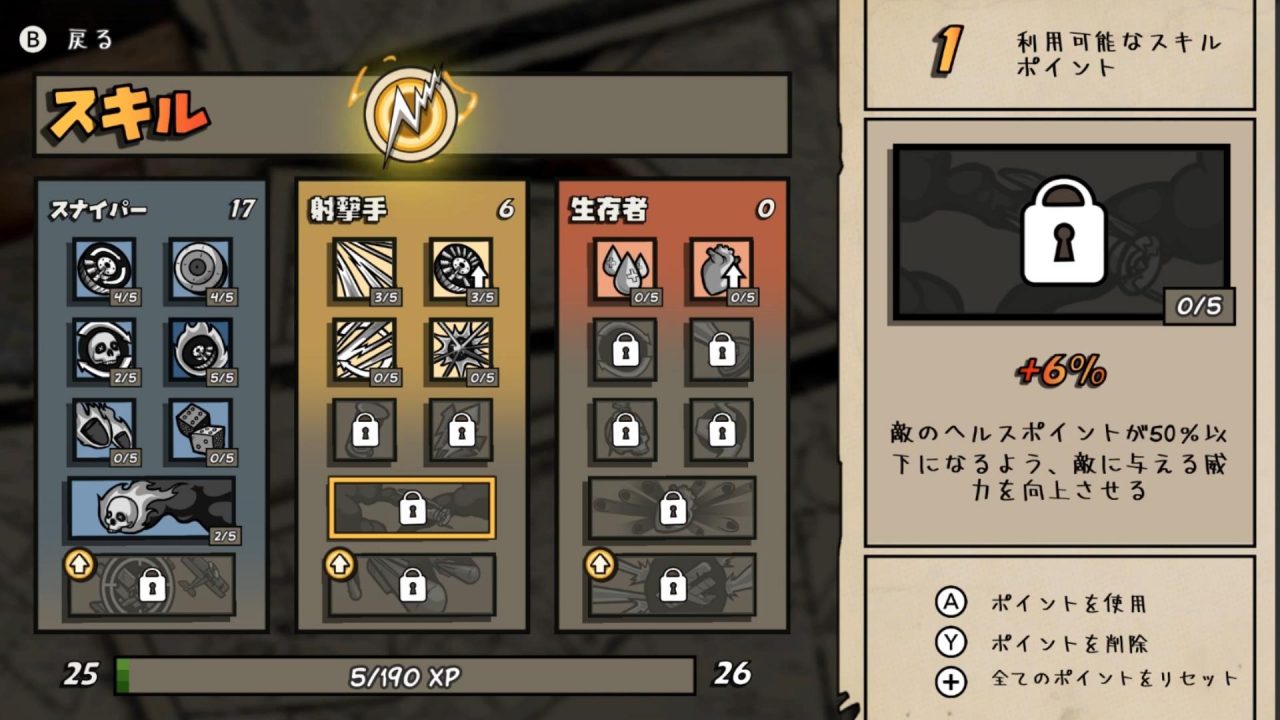

After going through the translation spreadsheet and watching the Japanese game footage a few times, I jotted down a few notes for SEED Interactive. I’ve listed a few of the problems below, some big and some small.

Mistranslations & Peculiar Choices

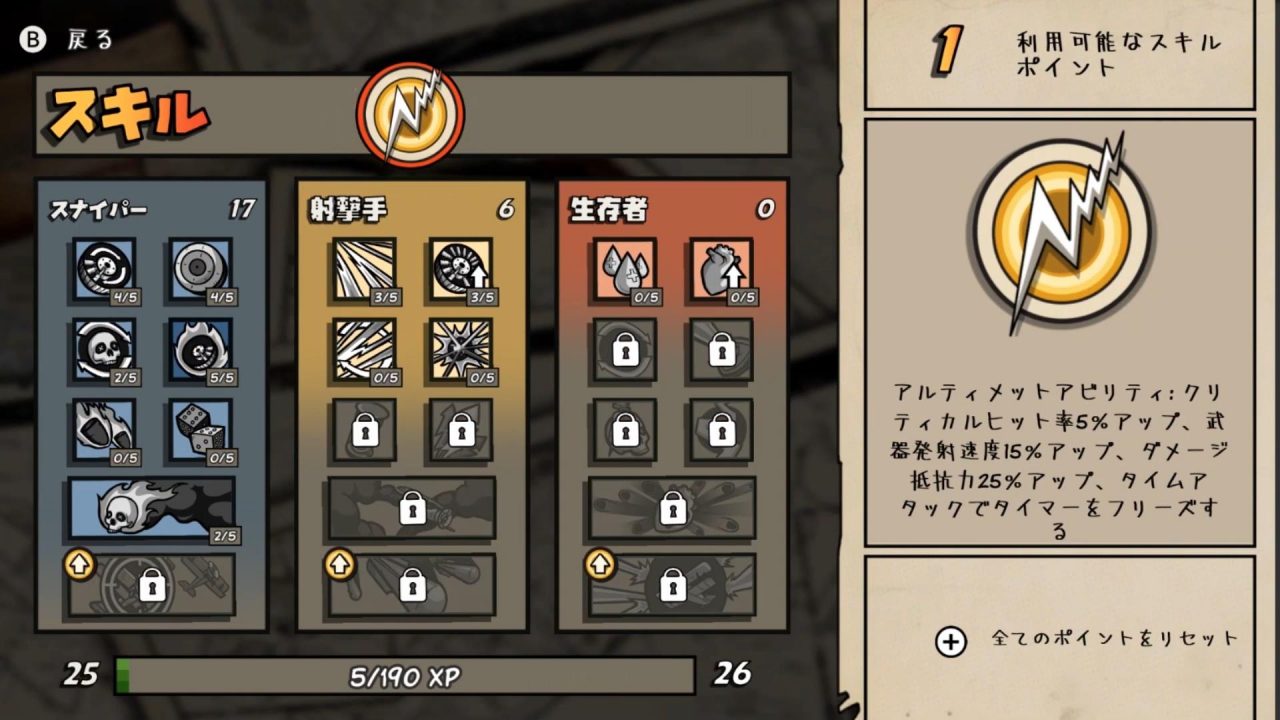

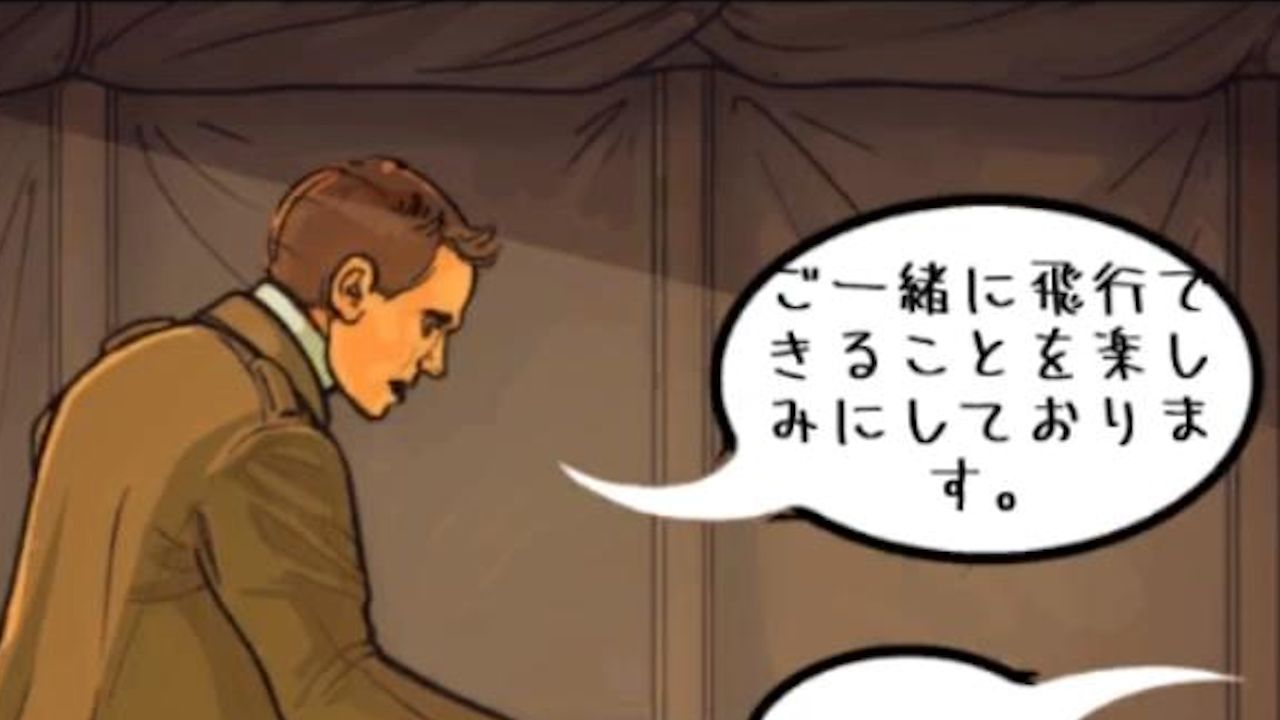

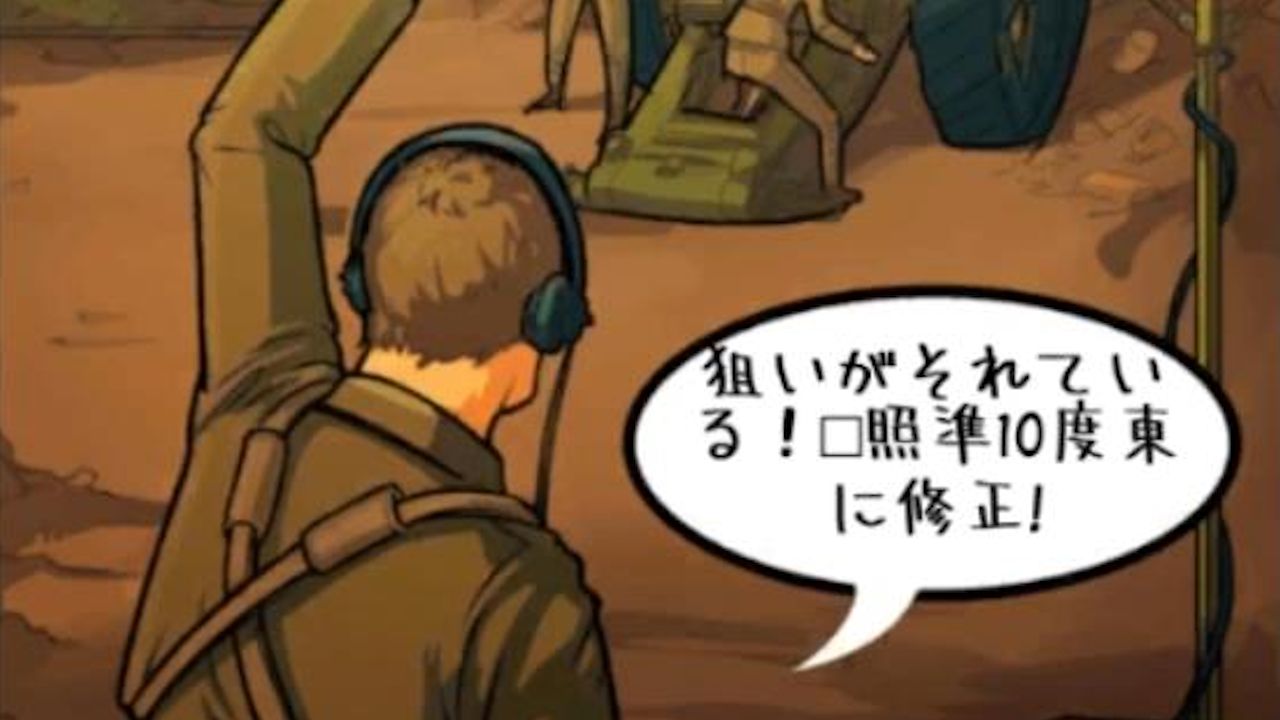

![Description text was regularly awkward and inconsistent. For example, although not technically wrong, the English line "Co-op with another player to increase your change [sic] of survival" transformed into a polite Japanese request: "The player will please cooperate with other players and increase the possibilities of survival". Description text was regularly awkward and inconsistent. For example, although not technically wrong, the English line "Co-op with another player to increase your change [sic] of survival" transformed into a polite Japanese request: "The player will please cooperate with other players and increase the possibilities of survival".](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/sky02-1280x720.jpg)

Unnecessary Translations

Missing Translations

Translation Tone Issues

Text Issues

Post-Translation Check

After I wrote down my translation notes and thoughts, I sent them back to a producer at SEED, along with the recommendation that the game get retranslated or at least fixed up by a different translator. I suggested a couple English-to-Japanese experts I follow on social media, but reaching out to random people on social media who only post in Japanese was understandably intimidating:

Thank you Clyde! This was very helpful (even if it now means more work for us 😆)

I wanted to contact those guys on Twitter you recommended but they are not really approachable – almost everything is in Japanese, they don’t have emails, and their websites lack English versions. So I think we will opt for a specialized video game translation agency – a quick search yielded (company) and (company) as potential options. Please let us know if you know anything about their credibility, lest we end up with another poor-to-mediocre translation 😬

Unfortunately, I hadn’t worked with either company nor heard anything much about either one, so I couldn’t offer much advice about them.

Some time later, the producer at SEED sent me this e-mail:

We then ended up picking (company) to enhance the translation for us, but we are underwhelmed with the result. We’ve actually sent them your doc to better convey what we want, but what we got from them was a grand total of 13 improvements! So a far cry from leaving portions of the text in English and other suggestions you said would make the game feel truly localized.

I looked at what this second translator had changed – and it wasn’t much. I don’t think they fixed much of anything – they mostly just translated the dozen lines of text that used to say “NO TRANSLATION”. And even then, some of those ended up mistranslated too. Gah!

The whole thing cost us US$190, which is not a huge sum but still feels like a waste since it didn’t get us what we need. It seems that finding a good Japanese localization partner is extremely difficult.

By this point, everyone was understandably frustrated.

Second Thoughts

With the amount of time and money already poured into the Japanese localization, the team at SEED had to decide whether to continue to pursue a Japanese release or just ditch the idea altogether. Would all this time and money even be worth it in the end?

SEED decided to keep at it, but time and money were getting low:

In fact, what we will probably end up doing now is try to find an exchange student from Japan who is also a gamer here in Toronto and give him some cash to help us…

In the end, though, this plan didn’t work out:

We never got to searching for a Japanese gamer in Toronto since we decided to cut our losses and release the translation as is. We’d love to be able to sink more time and money into making it perfect but it’s simply not a feasible proposition for an indie studio like ours. That’s why we would love to share our story and hopefully help other people out there in a similar boat.

So it sounded like everything was set and decided by this point… but things weren’t over yet.

Unexpected Steps

There’s more to game translation than the main translation itself. Every project has lots of little side things that need to be dealt with that don’t seem obvious at first.

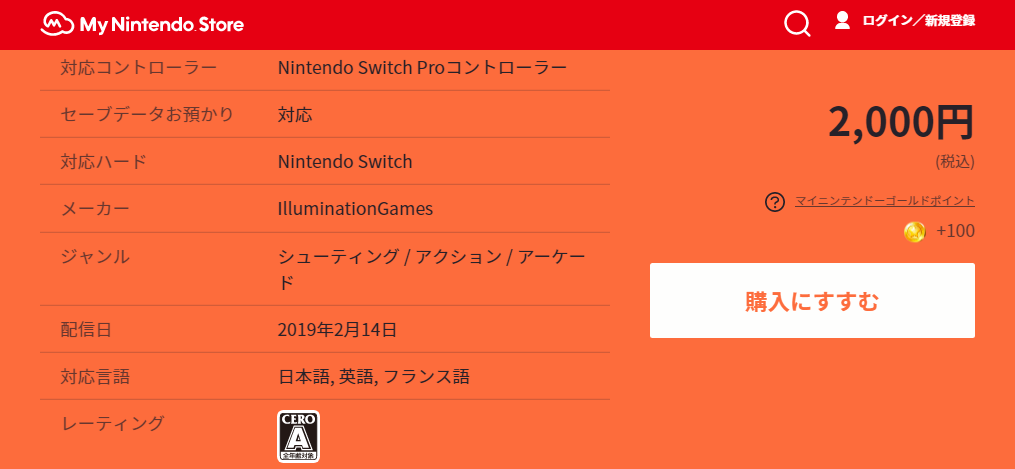

In the game of Skies of Fury DX, the developers had to implement a new font, program a new shading system for the Japanese text, and translate external assets (such as digital store descriptions) into Japanese.

The CERO process was more lengthy and challenging than expected. They conduct all their business exclusively in Japanese which as you can imagine was a problem. Luckily, we could at least write to them in English – even though they would still reply back in Japanese! We had to use Google translate to figure out what they were saying. However, they would often send us PDF forms that Google translate couldn’t help us with. In those cases we would have to more or less guess what goes into what field!

Another issue we had was making payments to CERO – we had to wire money to their bank account, but it was notoriously difficult to figure out how much our bank and their bank would eat up in fees. Because of this we ended up short changing them so we had to make up for a difference in a second transaction (which ate up more fees!!)

All in all, getting CERO’s certification cost us approximately $5000 CAD, which is not a trivial amount of money to recoup from Japanese sales alone.

This is another reason why I strongly recommend translation and localization companies that specialize in games only – some English-to-Japanese game translation companies will even act as professional advisors, serve as in-betweens, and deal with all the Japanese organizational bureaucracy, in addition to handling the actual text translation. Some companies will even handle the game’s marketing and promotion for you.

The Long Wait

I helped SEED navigate the CERO stuff a little bit, but we went our separate ways for a while after that. I kept an eye on the Japanese eShop to see how the final Japanese version of Skies of Fury DX turned out, but months passed and it never appeared. I started to assume the Japanese release was called off.

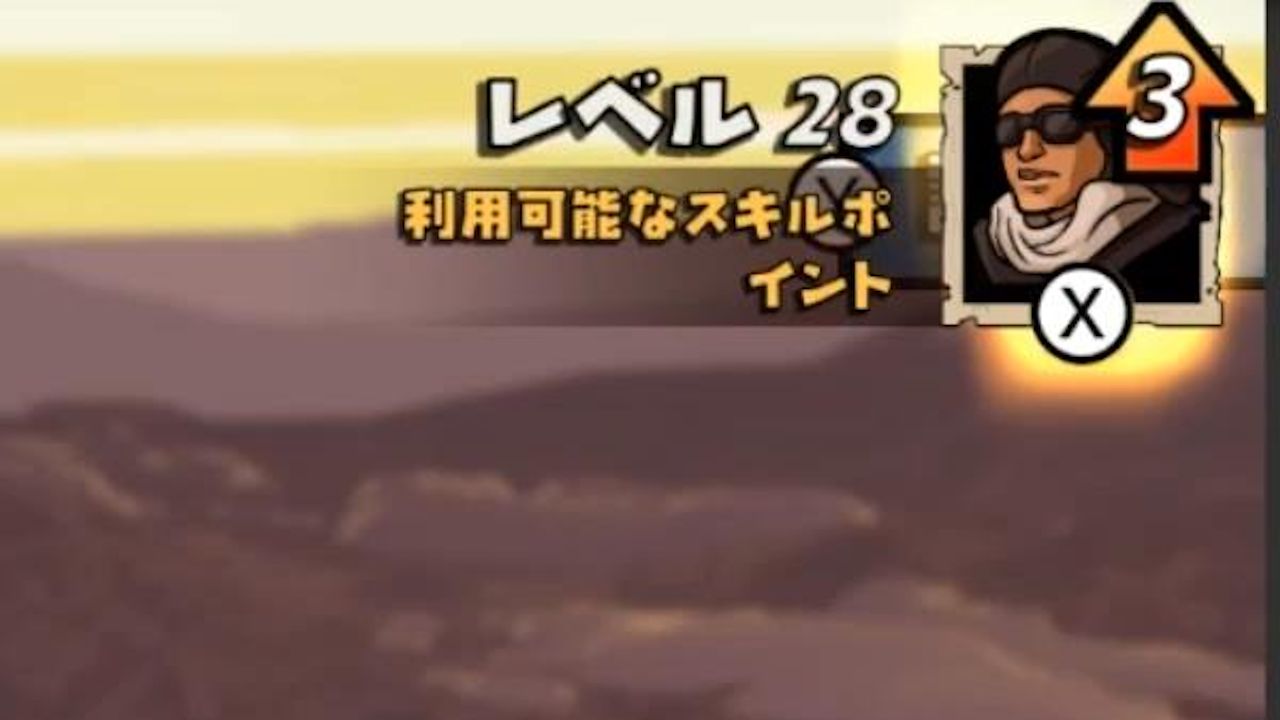

Finally, in February 2019, the game was released in Japan. The eShop listing said the game had Japanese support… but when I bought the game, it was literally exactly the same as the English game. There were no language options or anything else.

I e-mailed SEED and let them know about the problem with the Japanese release. It turns out the Japanese update had gotten stuck somewhere in the process and nobody had noticed or been notified. The issue quickly got resolved, and the Japanese language version was finally available for download in April 2019.

I briefly played through the final release, and was glad to see that a few of the fixes I suggested had been implemented. Most of the translation problems still remained, however.

It’s now May 2019, which means the Japanese language version hasn’t been out long. Unfortunately, the game debuted without a Japanese translation and stayed that way for two months, which probably drove interested players away. It’s also been drowned out by the torrent of other games on the Nintendo Switch since its debut, so I haven’t seen any comments or articles about the game in Japanese yet.

Lessons Learned

After the Japanese version was finally updated and available, I asked the team at SEED a few questions:

- If you could go back in time, what would you tell yourself before starting the Japanese version?

- Similarly, what would you suggest to other developers who are interested in localizing their games into Japanese?

The answer was pretty simple:

Find a Japanese speaker who can translate the game (or at least address localization questions) and handle CERO emails. It’s quite an undertaking otherwise.

And here’s another lesson the team learned:

The problem with good localization is that it costs money to do it properly, and it’s not clear whether it will recoup the cost. So it’s definitely a shot in the dark.

Final Thoughts

It’s easy to point and laugh at games that get bad translations, but sometimes it isn’t always obvious how things got that way behind the scenes.

In this instance, the game developers were proud of their work and wanted to release it in other languages. But a number of factors tripped them up, including:

- The developers’ inexperience with the localization process

- Poor work from two different translation providers

- The frustration of trying to get things fixed

- Budget concerns as the process wore on

- Navigating bureaucracy in a foreign language

The biggest lesson that comes to mind is this: if you’ve released a game, you probably spent years and lots of hard work and money to develop it. You’ve created a complex thing, so if you want to translate it and release it in a different language, you can’t simply hire a translator like you would a plumber and let them handle everything. You will need to hire a specialist, of course, but you’ll also need to be pretty closely involved from start to finish.

The translation industry is massive and confusing and daunting for newcomers, as we’ve seen here. What’s more, game translation – and entertainment translation in general – is rarely straightforward. It’s a constant battle against unexpected problems. But it’s my hope that this inside look at the process can help other creators avoid those mistakes and improve their own localizations.

If you're an indie game developer and have had similar experiences with getting things translated, let me know - I'd love to hear more inside stories like this. Or if you're looking for some more articles about English-to-Japanese game translation, see here!

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/pressstart.jpg)

Well, it’s obvious that if your Japanese stuff ain’t gonna cut it, why even bother in first place?

I’m not C|yde, so i’ll speak for myself: it’s because good translating (at least trying to) actually matters, because bad translating can have unpredictable (generally bad) consequences.

True, it really does. And that’s why translations should be done with precision and care. So yeah, this site definitely needs more articles like this. English-to-Japanese translations should be equally valid as the usual Japanese-to-English ones.

It’s the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Unskilled translators don’t even know that they’re unskilled.

I’m curious about “dab” being translated as 名人 on that spreadsheet. Is that what the pose is called in Japanese?

I’m not really sure it’s as big of a thing in Japan, but I’ve only seen it as ダブポーズ or DABポーズ myself so far. Here’s an article about it, in fact: https://sygmwt.com/1744.html

If Wikipedia is to be trusted, “dab” is a very obscure term for an expert. https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/dab#Etymology_2

Yes, like a “dab hand”.

LoL continues to grow and expand. Awesome work, Mato. Missing your streams. It’s fun trash talking SAO.

From what I have seen playing Japanese video games (plus other entertainment), they use English words like WIN, LOSE, VICTORY, DEFEAT, ON, OFF, STAGE, HP, MP, etc. all the time. They know what these words mean. So it seems very odd the translator went and translated VICTORY as 勝利.

It would be like translating the French sentence “déjà vu” to “seen before?”. That is the correct translation, but déjà vu is such a common French term that is used in the English language, plus English users knowing the meaning of the word, it would make sense to just use déjà vu.

It helps that déjà vu is so common that dictionaries consider it to be an English phrase.

That’s exactly what I have observed as well. And funny thing is, it clearly seems very natural. A good rule of thumb is that only the actual text such as subtitles appears in Japanese while text on various interface elements won’t. And of course, expect these to be translated as well when it’s time for German/Italian/Spanish/French versions to come out. Like, picture a typical RPG battle menu. Chances are, the menu items as well as the text on hint bar will be in Japanese as expected. At the same time however, the ‘command’ header will appear in English instead and so on. And even then, you get games such as the recent Persona games where even menu items will appear in English as well. In general, it’s kinda fun to look around and see how much English you will encounter. And as the example game of this article shows, somehow western developers have this habit of translating literally EVERYTHING to Japanese no matter whether it’s aesthetically pleasing or not. Of course, this can happen in Japanese-developed games too albeit usually they’re titles meant for younger audience that are still learning to read. ‘Course it’s not a fast and hard rule and you get titles such as Ace Attorney where there’s absolutely no English in sight, labels included. Overall, fascinating stuff.

Fascinating article, would love to see more of these! With how complex the translation process is I’m kind of amazed any indie games get translated at all.

I kind of wish you’d name names for the benefit of developers trying not to get ripped off, but that’s probably unprofessional, huh.

Yeah, I wasn’t sure about what to do about that, so I figured I’d let the client decide whether or not to go public with those details.

Wait, having games rated is a pay service? And it costs HOW much? How do solo devs compete in that sort of market?!

Yeah, you gotta pay for ESRB and CERO ratings. Apparently $3000 is on the low end and it can get much more expensive depending on the game’s budget.