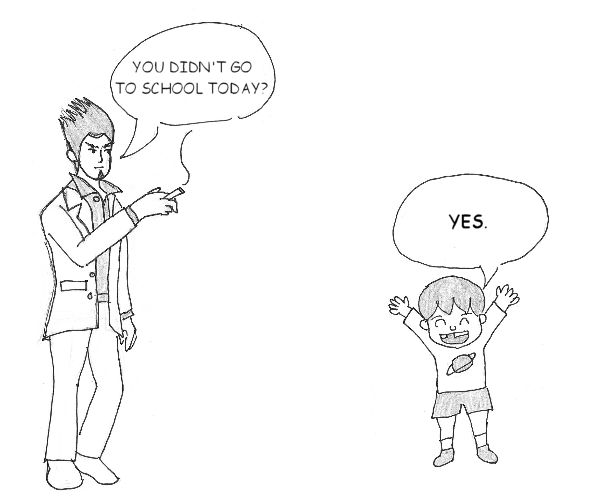

So what gives? Did someone mess up the translation? Did you just spot a big mistake?

It most cases, it’s probably not a mistake. This is because hai functions more like “correct” and iie functions more like “incorrect”. This normally does equate to “yes” and “no” in English… but not when a negative question is involved.

I could probably just end this article right there, but I thought this would be a good chance to look deeper into this language quirk, examine why it’s a translation problem, and then see how it’s been handled – and mishandled – in actual translations.

Agreement in English

In English, “yes” and “no” seem pretty clear-cut in meaning, but they become a little fuzzier when a question involves a negative.

What would that even mean? Are you saying “yes, I went to school” in response to the verb, or “yes, that’s correct, I didn’t go to school” in response to the whole question? A similar thing also happens if you answer with a simple “no”.

Of course, in everyday English, we’d probably instinctively add an “I did” or “I didn’t” for further clarification. But the important point here is that simple answers to negative questions can cause ambiguity in English.

Agreement in Japanese

Japanese is classified as an “agreement language”, which basically means that hai acts more like “correct”, and iie acts more like “incorrect”.

If you answer with hai, there’s only one interpretation: “that is correct (I didn’t go to school)”. And if you answer with iie, there’s only one interpretation: “that is incorrect (I did go to school)”.

In short, simple answers to negative questions aren’t ambiguous in Japanese.

Multiple Approaches in Translation

Negative sentences can be troublesome for Japanese-to-English translators. But, depending on the exact problem, there are two main approaches to this translation issue:

- Restate the question so that it logically fits with what comes afterward

- Restate the response so that it logically fits the original question

Approach #2 is why you’ll sometimes hear hai translated as “no”.

Anyway, enough with the theoretical stuff – let’s look at some actual examples of this negative question problem and see how they were handled in translation.

Approach #1 Example

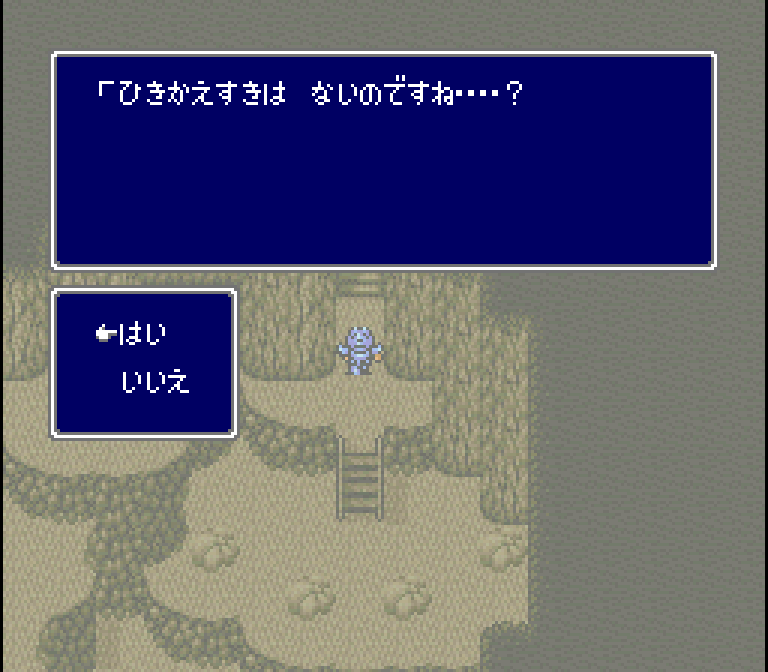

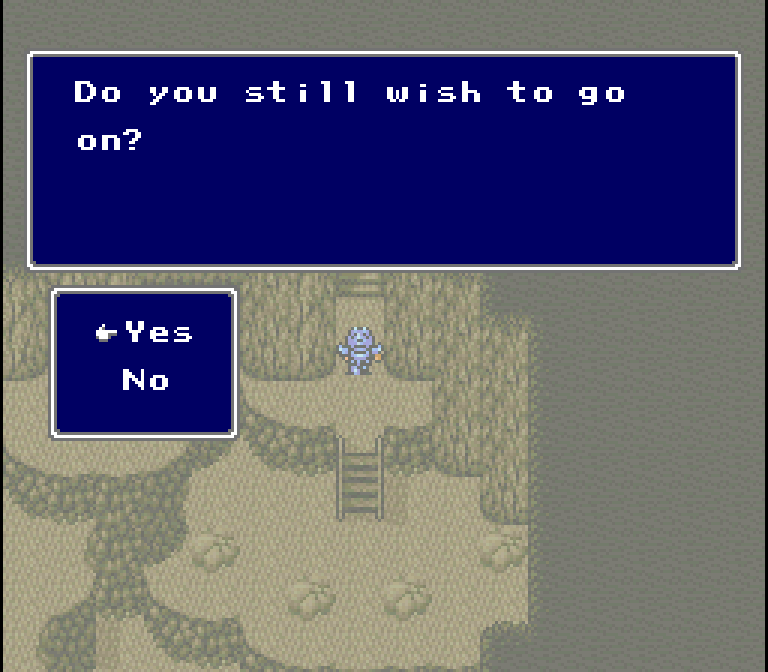

Early on in Final Fantasy IV, a spooky voice in a cave keeps telling you to turn back or face the consequences. Then, when you reach the cave’s exit, the voice asks one final question. You’re then given a choice. Choosing the top option moves the story forward and starts a boss battle.

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| You don’t intend to turn back? | Do you still wish to go on? |

| hai / iie | Yes / No |

As we can see above, the original Japanese line is a negative question, meaning we’re in tricky territory.

So, let’s say we’re a badass and that we have no intention of turning back. If we’re not going to turn back, we could say either of these things to get the same point across, even though one is “yes” and one is “no”:

- Yes, that’s exactly right, I ain’t turning back!

- No, I ain’t turning back!

These two are effectively the same, so which one is the player supposed to choose?

To avoid this potential confusion, the original question was restated as a question without a negative. Now it’s clear that “yes” means “yes, I still wish to go on” and that “no” means “no, I don’t wish to go on”.

Approach #2 Example

In this scene in the Fairy Tail anime, Gray asks Mest a negative question. In Japanese, Mest responds with aa, a less formal version of hai.

In the show, Mest hasn’t heard from the guy in a year. This is why the subtitles translate aa as “no” here, when you’d normally expect aa to mean “yes”.

An alternative solution would’ve been to translate aa as “that’s correct” or “indeed”. Yet another solution would’ve be to restate the question, similar to the Final Fantasy IV example above, so that the aa could be left as “yes”.

Exceptions

There are occasional exceptions to this yes/no problem, especially when the negative question involved is an invitation or a request. In these cases, it’s often okay to keep everything as-is.

For example, at one point in The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, this girl asks you if you’ll help protect her farm:

|  |

| The Legend of Zelda: Mujura no Kamen (Nintendo 64) | The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask (Nintendo 64) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| You’re a boy. Won’t you give it a try? | You’re a boy, won’t you try? |

| hai / iie | Yes / No |

As we can see, the original Japanese line is an invitation that uses a negative question. In a straight translation, this already works pretty logically in English, so there was no need for the translator to take any extra steps.

Problems in Action

Sometimes this negative question problem goes unaddressed in translation. Here are two examples that I can recall offhand, but I’m sure I’ve seen more.

Example Problem #1

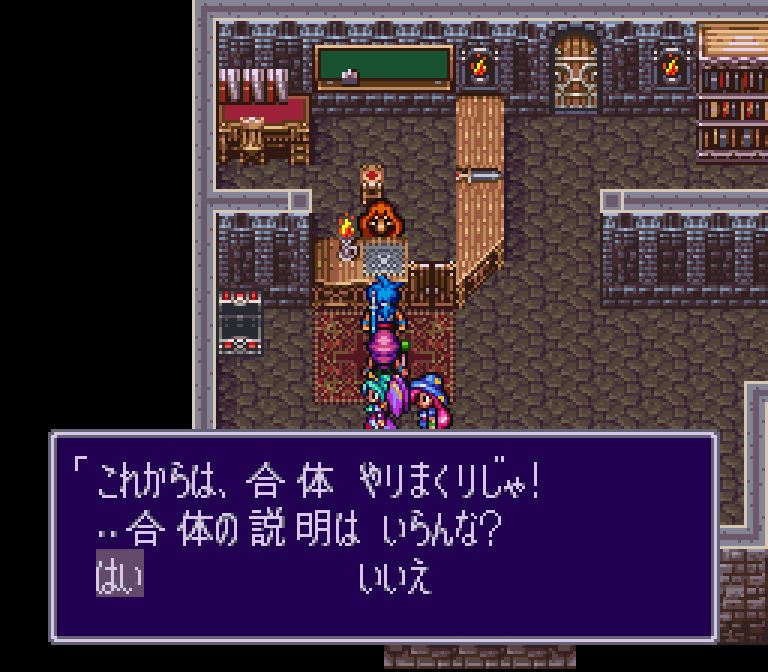

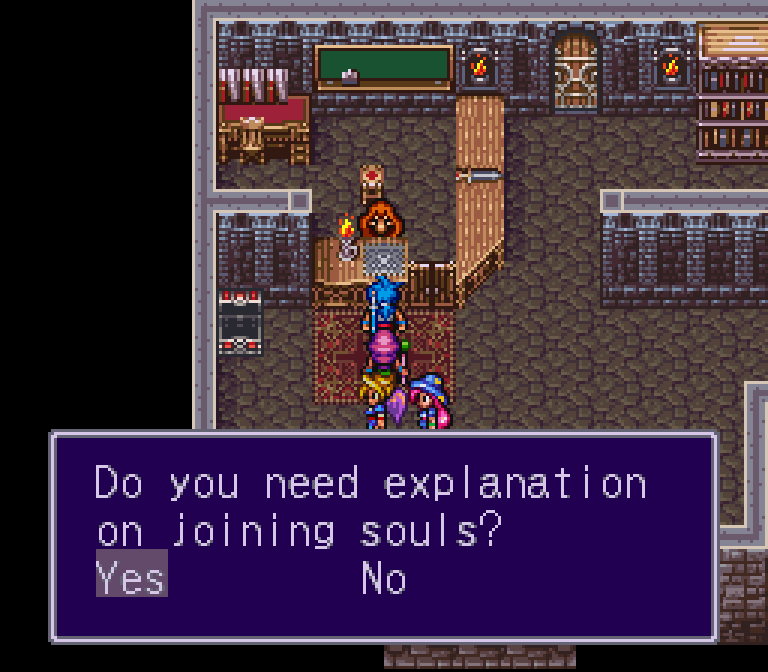

In Breath of Fire II, this character offers to explain how a complicated gameplay mechanic works:

|  |

| Breath of Fire II (Super Famicom) | Breath of Fire II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| I take it you don’t need an explanation of Joining? | Do you need explanation on joining souls? |

| hai / iie | Yes / No |

Answering with the first option skips the explanation and closes the text window. This is because answering the negative question with hai means “that’s correct (I don’t need an explanation of Joining)”.

However, the English translator mishandled this negative question problem. As a result, choosing the first option still closes the window without any explanation given. So if you do want to see the explanation for this gameplay mechanic, you have to choose “no”.

Example Problem #2

This problem is a little different, but still touches on some of the issues we’ve seen in this article.

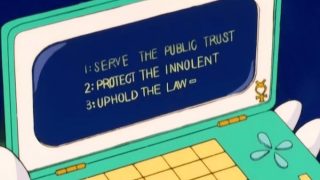

At one point in Dark Souls, a character offers to teach you magic. But then he follows it up with one last question:

After this, you’re then prompted to say “yes” or “no”.

If you want to learn his magic, which one should you choose? Are you saying “yes” to learning magic or are you saying “yes” to not liking magic? If the latter, does “yes” mean “yes, I don’t find magic unsavoury”? Does “no” mean “no, I don’t find magic unsavoury?”. Here are some players’ reactions:

In Japanese, this character’s line is: “Or, perhaps, are you one who is disgusted by magic?”. This more straightforward wording, together with what we’ve covered in this article, makes the question a bit less confusing in Japanese.

Example Problem #3

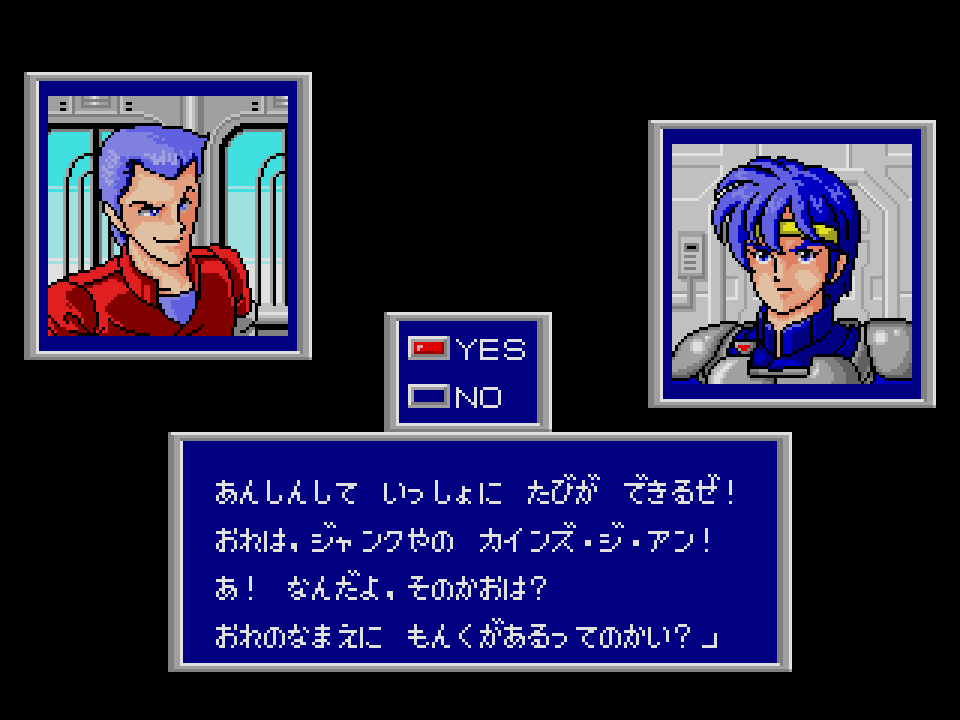

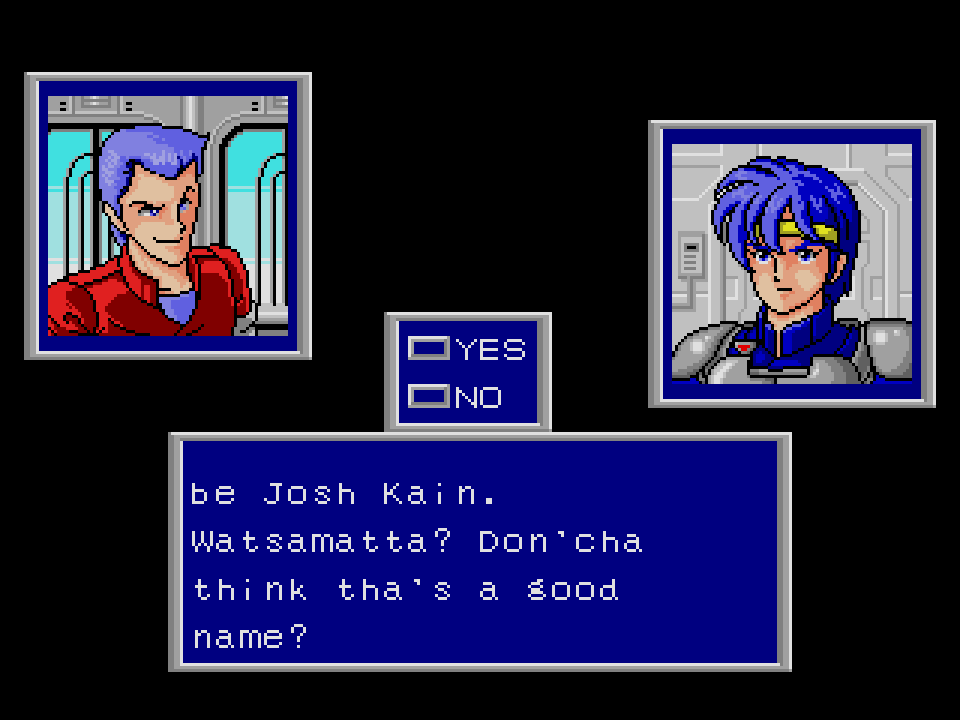

This example from Phantasy Star II demonstrates a slightly different way that yes/no questions can get messed up in translation.

If you talk to your party members in one area of the game, you get the option to rename them. Most party members ask something like “oh, do you want to change my name?”, so answering with a “yes” or “no” makes perfect sense.

But one character, Kain, asks a negative question in English:

|  |

| Phantasy Star II (Mega Drive) | Phantasy Star II (Sega Genesis) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| What, you got a problem with my name? | Don’cha think tha’s a good name? |

In Japanese, answering with “yes” here means “correct, I have a problem with your name”. So choosing “yes” allows you to rename him.

In English, not only was Kain’s line changed into a negative question, it also asks the opposite of what the original line said. This means that if you want to rename him, you have to say “yes, I do like your name”. That would only make sense in Moonside or on Opposite Day.

Other Uses of Hai

I should also briefly mention that hai is used in many other ways outside of saying “yes” or “no”. Sometimes it’s used as neutral filler speech to indicate you’re listening. Sometimes it’s used as a sign of acknowledgement. Sometimes it’s used as a delineating device to indicate a change in topic. Sometimes it’s used as a way of saying “here you go”.

Basically, hai has many different meanings and uses in Japanese beyond “yes”.

Final Thoughts

This has all been a long-winded way of saying that hai and iie aren’t as simple as “yes” and “no” in Japanese. These nuances aren’t something they teach you right off the bat in Japanese language classes or textbooks, so it’s common to hear this sort of thing from beginning students:

I’d say it’s probably just the opposite, though – if you ever see hai translated as “no”, it’s probably a good sign that the translator has some experience and knows their stuff.

Anyway, hopefully this clears up some misunderstandings about the topic and saves future students from this confusion. Also, I’d love to collect more examples of this yes/no problem for future stuff, so if you’re a translator and can recall any examples that would fit on here, let me know. Or, if you’ve seen other yes/no mistakes in game translations like with Breath of Fire II, let me know that too!

If you liked this article and are just starting to study the Japanese language - or even if you barely have a passing interest in Japanese - you'll probably like these other articles I've written about the language too. Check 'em out!

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/pressstart.jpg)

I also like to think of hai as another way of saying “Understood” or “Gotcha”. In anime, little kid characters often respond to their parents with a cute “Haiii~” when the latter tells them to make sure their room is clean and to finish their homework before dinner. The same thing happens in school settings, such as for cleaning the classroom or asking a student to come to the board to solve a problem.

That Breath of Fire II threw a lot of us for a loop back in the day, myself included. I thought the localization flipped the responses at the time.

This reminds me, Yuna from FFX originally interjected ‘hai’ in the original dub which was replaced with the somewhat awkward ‘okay’ in most instances due to the need to match the lip movements.

That is interesting. I haven’t heard much of the Japanese voices for FFX, so I wasn’t aware of that.

Holly Kujo also replaces “hai” with “okay” in the Stardust Crusaders dub, though in her case it works perfectly fine.

There’s also cases where the speaker saying “yes” or “no” in potentially an unexpected way is also nodding or shaking his or her head appropriately. That means the translator really needs to tweak the question to elicit the obvious visual response–and try to be smooth about it.

Honestly, this kind of strikes me as just one small example of the larger point that translation is more than just replacing one language’s words with the other. It’s generally easy to see how “hai” would still be “yes” in these situations, it’s just that it’s saying “yes” to something that doesn’t necessarily match what us anglophones would think we’d be saying “yes” to.

I think another super common one is “ja nai”, “jan” and the like. It’s not like English speakers are constantly being totally literal either, but if you don’t stop for a moment to consider what’s actually being expressed, it can throw you.

Monoglots seem to struggle to understand how differently a foreign language can be from their own in every possible aspect. Why the examples here of some frustrated people having a hard time understanding that “hai” and “iie” aren’t directly equivalent to “yes” and “no”, and that sometimes translating “hai” as “no” is neither a mistake nor changing what the original script was meant to say.

Then again, this whole site was made to open the eyes of those who think they know way better about this subject that they actually do.

It’s not really a monoglot thing, it’s more an issue of classes and dictionaries explaining that x means y, having this be the case in both the example dialogues you study with and whatever instances you run into in the wild, and then suddenly getting exposed to a situation where x means something completely different and getting very confused. Unless you never encounter the language you’re learning outside textbooks and classes that will explain these things when they get to them, this is extremely universal.

I’m now thinking of how many European kids back in the day got awfully confused when Lucas said he loved the Power Glove because it was bad. That’s NOT a meaning of the word you’ll learn in class or find in a dictionary.

It’s probably best to say that it’s a combination of things. The more reasons you have to be ignorant of language, the more ignorant you can be expected to me.

Monoglots don’t have the frame of references with which to compare the attributes of one language to another, and us who started off as anglophones are probably the worst, since we can see the worldwide spread of English, and it’s very easy to be fooled into thinking that English is some all-encompassing thing. Sometimes we can even struggle with the idea that there are sounds in other languages that aren’t in English.

Additionally, we don’t really need to know a ton about languages that we’re surrounded by, so while it might be easy to think native speakers are experts at their own language, it isn’t all that true. We can often have misconceptions about our own language. Consider how many common phrases are so often confused that we can recognize the intent even if they no longer make sense: “for all intents and purposes” becoming “all intents and purposes”, “I couldn’t care less” becoming “I could care less”. And how many confuse “bemused” with “amused”, “ironic” with “unfortunate”, “literally” with “figuratively”, and so on.

It can get even more damning when you look at older or obscure language. How many students reading Romeo and Juliet in high school read the phrase “wherefore art thou Romeo” and assumed “wherefore” must have meant “where”, when actually it’s closer to “why”? “Thou” is generally understood to be an old-timey version of you, and we often think of it as grandiose because we don’t hear it in the average day. But how many know that “thou” was the singular and that “you” is the plural? Or that for a time, “you” was respectful and “thou” wasn’t? That leads to the weird situation where translations of the Bible uses a lot of “thou” to refer to God, which was meant to seem approachable but has the totally opposite effect for modern speakers.

The meanings of “wherefore” and “thou” might be more obvious to those who also speak German, where the equivalent of those words are still used. But how many English speakers would know that English and German are that closely related? Language history isn’t something we really need to know, so it’s another area that’s easy to miss and forms a lot of misconceptions. Whenever you see a spelling bee on television, the big scary word is always from Latin. Most English words are from Latin, but the language is closer to German at its core, and most of the most common words share history with that language. And we often think that since English came from England, and a particular version of London’s English is considered the standard, that that must be the original form. But London’s English is actually one of the fastest morphing because of the high international connection with that city; areas of Canada and the northeastern USA are closer to how English was spoken at the time North America was colonized, and if you look up reproductions of Shakespeare’s accent, you might find that it sounds similar to how a Scottish accent does today.

Often we think that there’s a certain proper version of the language, perhaps the original, and any deviance from it is improper. But language is constantly evolving, and the language we grew up with had evolved from how it used to be. If the average native English speaker looks at the oldest works of English, like the original text of Beowulf, they likely will be almost totally unable to read it simply because the language has shifted so much since “Hwæt! Wé Gárdena in géardagum þéodcyninga þrym gefrúnon· hú ðá æþelingas ellen fremedon.” And in fact, English didn’t just pop out of the ether in a completed form, but came out of other languages, which came out of other languages. Eventually you go so far back before writing where people are forced to just theorize how everything worked.

So, with all those misconceptions about how language works, we finally get it into our dumb little heads to study another one. We’re taught by someone else – perhaps someone who is simplifying things for our understanding – and we take it as dogma. Like, Japanese has no letter L, only the letter R. Everyone knows that, right? But some who have a little experience might go, well, no, that’s not quite true. Japanese has a sound that’s between the L and R where your tongue touches the roof of your mouth. But then people who know it better might go, well, that’s not quite true either, Japanese has some L and R sounds from other languages, but they have particular situations where they come out or they invoke different senses even though they’re identified as the same sound. The common knowledge seems less and less smart the more you know.

Perhaps the best way to conceive it is that sounds are a colossal variety of air movements, and our brains group particular ranges which we’ll recognize as distinct sounds. If we hear something unfamiliar to us but we still identify as speech, we just select whatever sounds closest and map it to the nearest range we’re familiar with. The Japanese “R” range doesn’t really match any English range neatly, but someone somewhere decided that it sounded closest to the R, and that eventually became a standard convention. We begin to learn these sound ranges from being exposed to a huge number of samples as we grow up. But what about people who don’t have that? There are a number of documented cases of human children being raised by animals. Since they aren’t exposed to human language in the animal world, they have difficulty learning it for the first time. After all, animal sounds tend to be substantially simpler than thise whole business of combining sets of sounds to create words, and then those words to create meaningful sentences.

I’ve gone totally overboard, but I think you get the idea. Our languages are incredibly complex systems, but we’re so exposed to them that we don’t have to think about that. It’s very easy for us not to appreciate that.

My point was mostly just that this happens to non-monoglot beginners to a language as well.

I’m not sure about that. As an ESL I can tell you, learning a second language helped me clear up many misconceptions I had about how languages in general work, as well as understand my own native better, like what its advantages and limitations are when it comes to approaching certain topics. Now that I’m trying to learn french and japanese, I’m being careful not to commit the same mistakes I did while learning english, like being too fast to make assumptions or look for direct equivalents in my own language, as well as not conform to just one or two frames of reference for something. In the case of japanese, since unlike english, it comes from a language family that has nothing to do with any european language, I’m pretty sure I’ll make some mistakes I didn’t even made while learning english, so I’ll have to be extra careful with the assumptions I come to. Also, I’ve seen some people who’re native of two languages who are perfectly aware of the huge differences between them, so not even being a native bilingual makes you ignorant of how different languages can be from one another.

Meanwhile, the only interest in foreign languages I see most monoglots on the internet (especially english speakers) having is whether or not they get a good translation of something to their own language (especially with japanese which, like I said before, couldn’t be more different from english) and seem to have cero interest in learning said language proper. Which is fine , you don’t have to feel obligated to do something you just don’t care about, but then they think they know how to handle a translation better than either someone who actually learned the language proper or an experienced translator. I guess people are kind of paranoic about changes in the script and censorship, and fail to understand that the translator is sometimes forced to make some changes for the localized script to make sense (even if they’re not trying to deviate from the original script) because the “literal” approach to translation just doesn’t work at all. Hell, they don’t even seem to know the difference between an translation and a localization.

My point is that, while I take it that not all monoglots are that ignorant about the whole topic of languages, I have yet to meet a bilingual person who actually is.

“but then they think they know how to handle a translation better than either someone who actually learned the language proper or an experienced translator.”

That’s called the Dunning-Kruger effect, where people with absolutely no skill at all in a field frequently assume that something is a lot easier than it actually is. Once you start learning a field, you realize how difficult these things actually are.

…I should probably be honored that you took me for a native English speaker there, but I WAS speaking from experience when I said this isn’t really a monoglot thing.

*shrug*

Well… I guess my last post was a load of crap then :/

“areas of Canada and the northeastern USA are closer to how English was spoken at the time North America was colonized”

It would be inaccurate to say American English hasn’t changed just as much as British English. Which dialect is “closer” to pre-revolution English seems to be a matter of opinion.

Of course both of them have changed, but they changed in different ways in different areas, and some changes are more dramatic than others. “American English” and “British English” are actually not uniform; they vary depending on what specific region you’re in.

However, I believe it’s generally agreed that the sort of American accent you’d hear from a newscaster is closer to the English accent at the time of colonization. A major point is that the British tendency to not pronounce the R at the end of words is actually relatively new.

I’m European and I can confirm I got confused when I saw the AVGN episode where he brings up the episode. I thought they actually in the movie said it was horrible.

Welcome the the English Language, where hot means cool and bad means good.

Funny enough I heard heard that in French, terrible (or something that sounds like that) also means good, for the same reason as bad means that in English

Can confirm! But it’s a fairly recent, informal use. It’s even more common in a negative sense: “pas terrible” means “(really) not great”. The original sense of “horrible”, “terrifying” etc. is also still in use, so you need context to know which one it is.

My native English speaker insticts always felt that the ‘I love the power glove. It’s so bad.’ line meant that it actually *was* awful, but it’s endearing in its awfulness. Then again, I’ve never seen the film.

If I’m not mistaken, the character was the “villain” of the movie, so him saying the Power Glove is bad is kind of a wordplay.

– The Power Glove is “bad”, as in it’s cool / good

– The villain, being a bad guy, like things that are bad instead of good

When we say straightforwardly that the Power Glove is bad, what we mean is that it isn’t very useful as a controller; it’s cumbersome, unintuitive, and slows rather than speeding reaction. Since the whole threat of the villain is that he’s supposed to be really good at video games, the Power Glove is probably supposed to add that that threat, not take away from it by being as useless as a controller as it is in real life.

I haven’t watched the movie, but think about, what if, in the movie too, the glove sucks? Then the villain would be even more fearsome, because if he can play well with that piece crap, he must be a god with a normal controller.

Either that, or it’s like Oro from Street Fighter III who sealed one of his arms in a pocket dimension because he’s such a ludicrously skilled and powerful fighter that only by doing that he can give his opponents a chance to beat him.

In the movie, it’s just meant to sell the Power Glove with an attempt at topical slang. It shows off that the bad guy has access to this controller (which means he has money) and it’s augmenting his skills so the heroes have something to beat.

The line survives memetically because of wordplay. “Bad” meaning “good” is outdated slang, AND the Power Glove was actually bad as in not good in real life. So it’s funny on a few levels.

Monoglot is a great term, and I will now use it.

Thanks!

Thank you for covering this topic. I’m curious how Laurentius’s dialogue is handled in other Dark Souls translations. As soon as I saw your post, I immediately thought of this scene.

I remember you talking about this before in the Final Fantasy IV comparison page. Still, it’s nice having a full article expanding on the subject.

The Breath of Fire II problem is likely caused by the translators not playing the game as they’re translating OR not having access to it and only being given text. That’s usually the cause of such problems from my experience.

I’m really curious as to the actual story of BoFII’s translation. I wonder what kind of mess it must have been for the team.

To me it seems like a first pass by somebody who spoke Japanese natively but had a rudimentary (at best) understanding of English, and rather than skim through the game to make sure it wasn’t completely broken, Capcom published it as is.

To be fair, even in English ‘yes’ doesn’t always mean ‘affirmative’. Off the top of my head, it’s also used as a sign of following a conversation e.g. “Yes, go on”, and as an exclamation denoting success/good fortune.

Gotta be honest, I don’t think the Japanese Dark Souls example is any clearer.

“I can share my spells with you”

Yes, I want to learn the spells.

“are you one who is disgusted by magic?

Yes, it’s gross and I don’t want to learn it.

I agree, they’re both just as clear, or rather, confusing. The confusing bit isn’t the meaning of yes/no or hai/iie, but that Laurentius is essentially asking two questions in one sentence. Technically the only question is “you find the magics unsavoury?” but it’s confusing to have a character offer something, then go back on it to instead ask for an opinion and then only give the player “agree” or “disagree” as an answer. In both English and Japanese, it would have been a lot clearer for players if the writers denoted what they were supposed to “answer”, i.e. “No, I would like to learn magic” and “Yes, I dislike magic”.

In Phantasy Star II, whenever a new character joins they say something related to their name, prompting a choice on whether you want to rename them.

For all but one it’s localized fine, but with Kain, the question was “Don’cha think tha’s a good name?”

But just like everyone else “yes” means renaming him and “no” means keeping his default name.

In Japanese, the question was more like “What, you got a problem with my name?”

Whoa, thanks! I actually have screenshots of those handy, so I’ll add them to the article.

Just out of curiosity, in the Breath of Fire II case where they’ve given an incorrect translation that went unnoticed until it was published, would the translator face a penalty of some sort?

No, not really. In this specific line I’d actually place the final blame on the lack of QA. But it’s just like anything else – BoF2 has some programming bugs, does the programmer get penalized then? Same with crappy art, bad music, etc. Mostly, the more mistakes you make the lower your reputation gets.

After leaning about how some languages handle agreement differently, I’ve become a bit more conscious of how to agree in English and I will use “correct/incorrect” rather than “yes/no” if the latter could possibly cause confusion.

I know this is about Japanese but in my language we have something strange. For example “Podoba ci się?” (Do you like it?) “Tak, podoba.” (Yes, I like it) or “Nie, nie podoba.” (No, I don’t like it)

Easy, right? But when it’s negative question: “Nie podoba ci się?” (Don’t you like it?)

“Nie, nie podoba mi się.” (No, I don’t like it)

“Nie, podoba mi się.” (No, I like it) or just “Podoba”/”Podoba się” (literally This corresponds to my preferences/This is suitable for my taste)

For the record, the English yes/no system is actually very straight-forward. You say ‘yes’ when the verb is true and ‘no’ when the verb is false. What form the question takes is irrelevant.

Unfortunately, ‘grammarians’ in the 19th century didn’t understand this and argued that yes/no worked like it does in Japanese. That’s where the confusion comes from. But if you listen to people speak English naturally and unprompted, they follow the rules above.

In might be straight forward in theory, but it is definitely not 100% consistent as your last sentence implies. Case in point, I’m actually in the process of catching up on GDQ VoDs and during one of the interviews the interviewer asked a question, of two people, ‘You two don’t live anywhere near each other?’ One of the interviewees answers ‘No’ while the other answered ‘Yeah’, and obviously they both intended the same answer (that they do not live near each other).

I think what tends to help with actual spoken English, though, is that the inflection/expression can often help to clarify which way is intended when a single word response is given. If I answer back in a questioning tone, or with a confused facial expression, you’re more likely to understand that my response is in disagreement with the question. Also, I feel that it’s more likely that a person will add clarifying details to their response in the case that they are disagreeing with the given question (for example, in the interview question above, you might answer with ‘No, we do’ or ‘Yes we do’ instead) then if they are confirming it.

I’d argue “yeah” is different from “yes”. If I asked someone “do you not like cake?”, I’d take yes as “yes, I do actually”, but yeah as “yeah, that’s right, I don’t like cake”.

This is interesting cause.. in English (as in England, not American which is.. mm.. there are enough differences between English and American as there is between Chinese and Japanese and Korean. some the same, some the same with different meanings, etc.. it’s far more then regional like Cornish English, or Northern English.. anyway)..

in English, if someone asked you “You didn’t go to school?” and they replied ‘yes’, then it means yes, they didn’t go to school and anyone with any basic level of English knowledge would point out to any kids trying to be smart claiming “yes, they did”, are wrong and probably give them a little slap cross the ear.. ah.. the differences between English and American as SOOO wide.. it’s an series of articles in it’s own right (and there are tons online about it). However, due to the amount of cheap American shows, a lot of people are learning more American then English in the UK these days.. years ago, shows like Fraggle rock had the translation UK version, much like the German one etc.. We had ‘the captain’ replaying Doc.. but these days? they just show American versions, so people learn correct spelling is ‘color’, ‘jail’ and ‘donut’… I think American is closer to Engrish then English…

As a native speaker of Chinese, I encounter the reverse problem when speaking English. Even after several years of learning English, I still can’t wrap my head around this “if question is negative, reverse yes and no” process. As a result, I answer “correct” or “incorrect” instead of yes or no (when I remember to do so).

There’s an example of this in Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE (and its re-release, Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE Encore… don’t you adore that title?!).

When you learn a new skill, you can choose to discard it, e.g., if all of your skill slots are filled and you don’t want to give up your current skills. The game then asks you something along the line of: “So you don’t want to learn this skill?” Picking “Yes” means “I don’t want to learn this skill.” and picking “No” means “Actually, I do want to learn this skill after all.”.

I’ll try capturing a screenshot of it over the weekend.

Completely off topic but the kiryu drawing made me laugh , love it !

Interestingly, English used to have a four-fold system of yes/no responses. If you were responding to a negative question, you’d use “yes” to mean “yes, it is” and “no” to mean “no, it isn’t”, while if you were responding to a positive question, you’d use “yea” to mean “yes” and “nay” to mean “no”. Like most things in language, though, this wasn’t a hard-and-fast rule. Nowadays, you only really sea “yea” or “nay” in parliamentary procedure.