In movies and TV shows, characters flawlessly translate super-technical subjects on the fly without even blinking. Sometimes they’ll even translate ancient text on the spot and localize it so it rhymes perfectly in English!

In actuality, translation is much more complicated, and even the simplest things can stop a translator in their tracks for hours at a time.

In this latest Tricky Translations article, we’ll see how one of the simplest ideas of all – the concept of “I” and “me” – isn’t so simple when translating between Japanese and English.

Choose Your Character

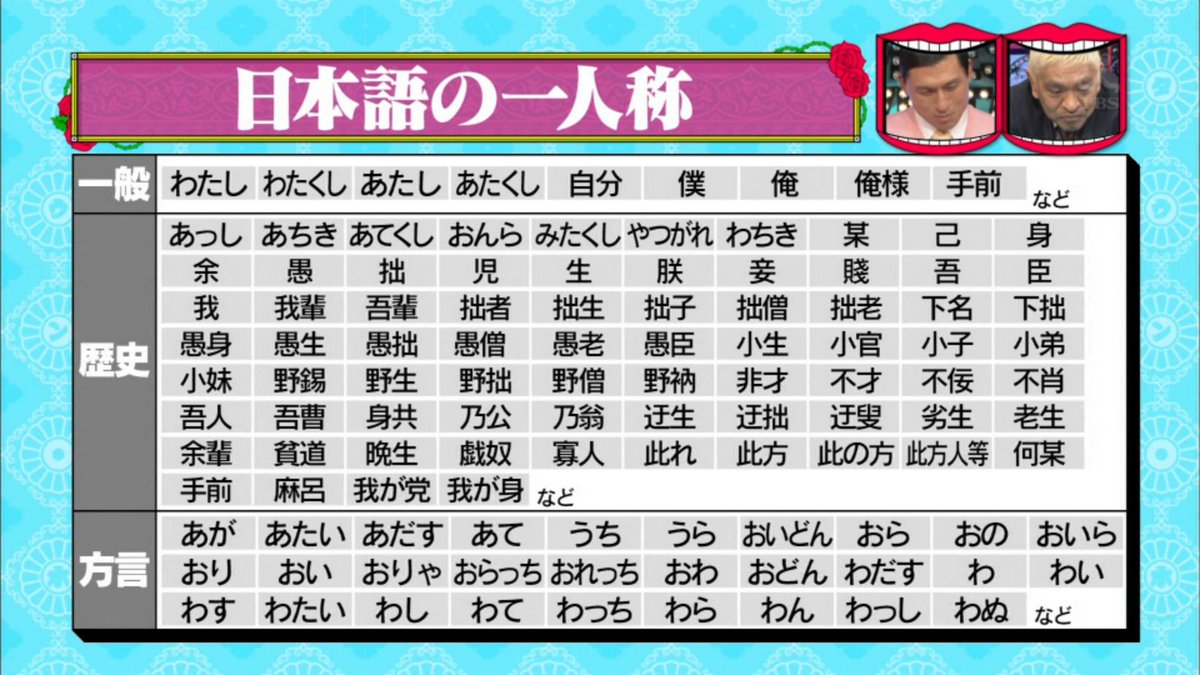

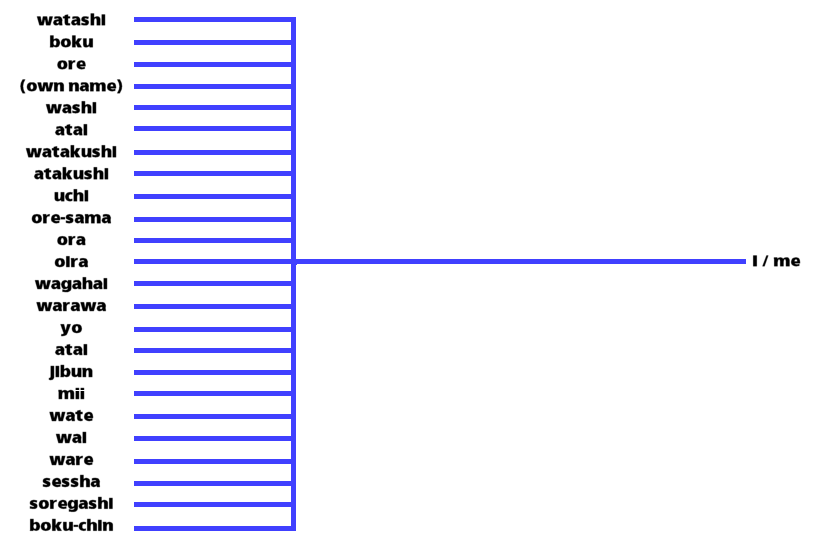

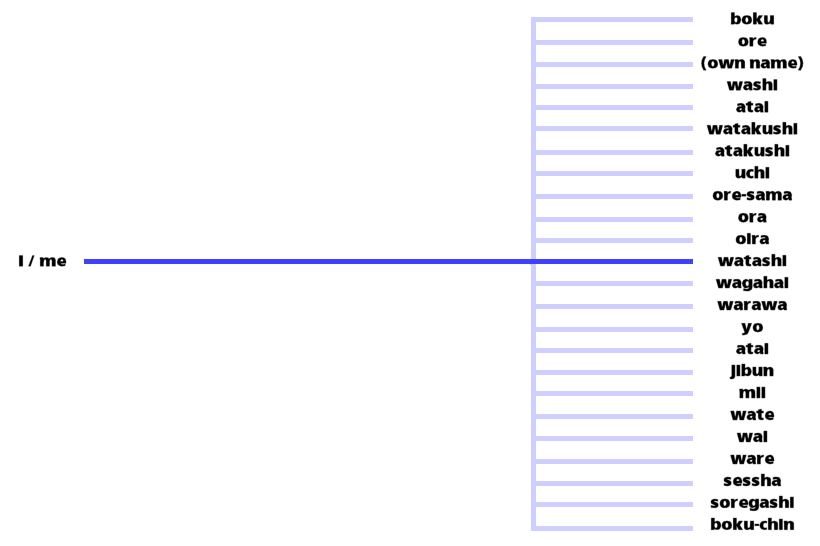

The Japanese language has lots of personal pronouns – words for “I” and “me”, in other words. Some are used every day, some are regional, some are historical, and some are limited to things like entertainment and academics. Countless books have been written about Japanese pronouns, and the topic even comes up in the mainstream media from time to time.

The cool thing is that you get to choose which pronouns you personally identify with. Of course, it’s a little more complicated than choosing one pronoun and using it everywhere – there are formal-sounding pronouns for formal situations, casual pronouns for casual situations, and so on. But it’s a fascinating system that doesn’t have a direct equivalent in English.

In this article, we’ll look at a dozen or so Japanese pronouns and see how they work. In particular, we’ll focus on how these pronouns are used in Japanese entertainment and who uses them.

Why So Many?

Why does Japanese need so many words for “I” or “me”? What are they even good for?

The quick and simple explanation is this: think of Japanese pronouns as clothing. The clothes you wear are an expression of who you are, what you’re doing, where you currently are, and so on. You probably wear a certain type of clothes while at home or hanging out with friends. When you go to a job interview, you probably dress up a little more to seem professional. And even when you’re just walking around in public, how you dress can offer clues about the kind of person you are.

Japanese pronouns work the same way. When you’re with friends, you might use certain casual pronouns that feel very “you”. But those same pronouns probably wouldn’t be appropriate in a formal or professional setting. And other situations might call for other pronouns too. What’s more, your pronouns preferences can change over time, just like your fashion sense might change.

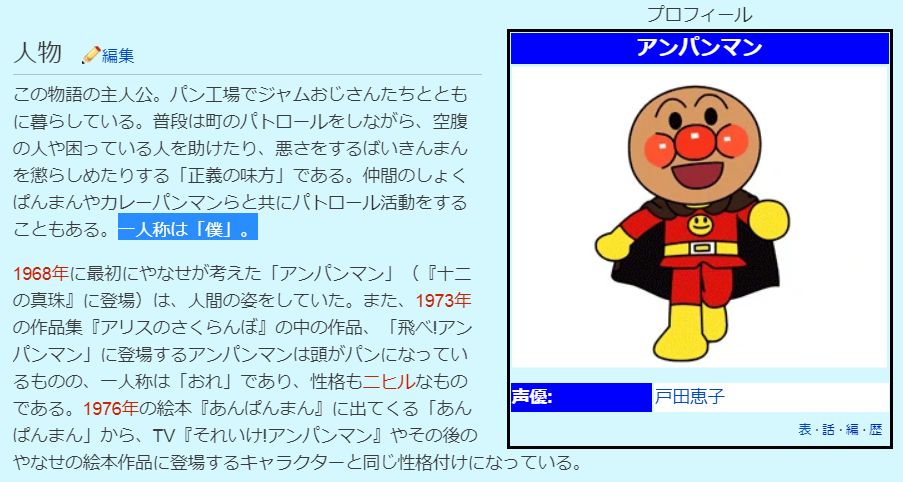

Basically, Japanese personal pronouns can say a lot about a person. In fact, it’s common to see a character’s preferred pronoun listed in their bio on wiki sites, fan sites, and the like. Japanese pronouns are that significant.

Everyday Pronouns

It’s hard to divide all of the Japanese pronouns into distinct categories, but if you study Japanese, you’ll probably encounter these three first. They’re used all the time in everyday situations and in entertainment.

Watashi

Watashi can be considered the default and most neutral version of “I” or “me” in Japanese. In formal situations or when being generally polite, watashi can be used by just about anyone. In informal situations, watashi leans a tad toward the feminine side.

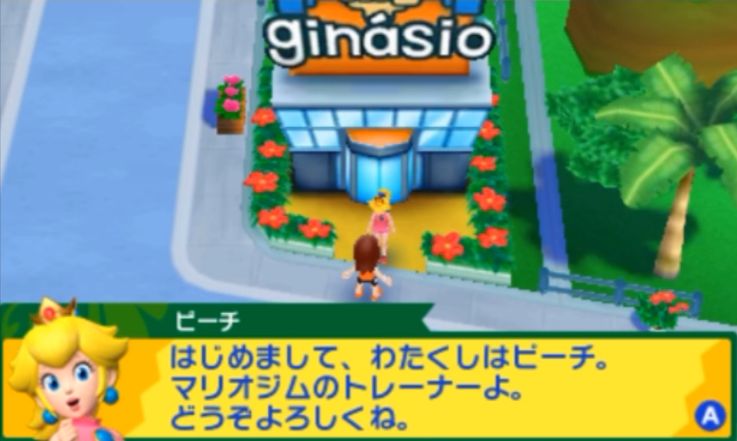

Since watashi is sort of the default, a list of popular characters who use watashi would be extraordinarily long. But here are just some examples to give you an idea of how wide its usage can be:

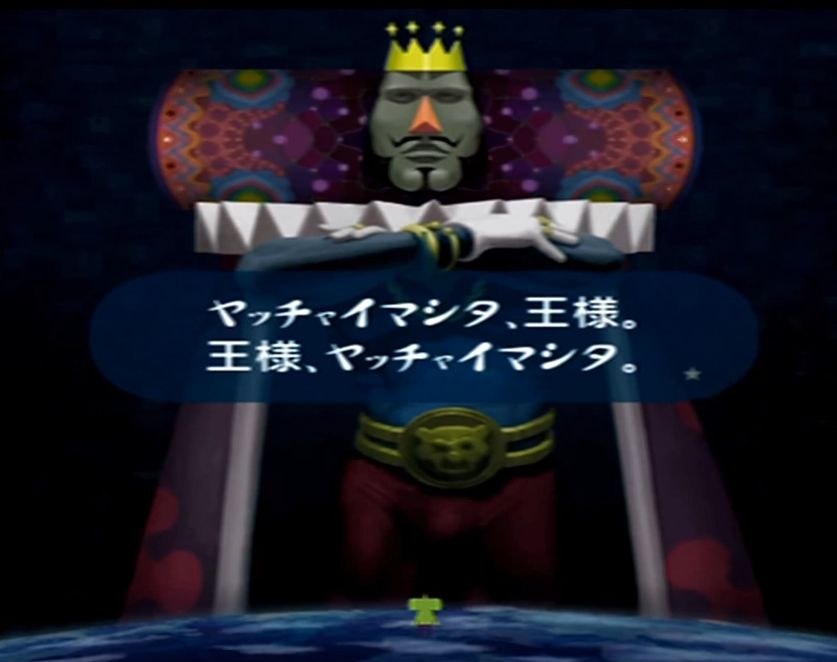

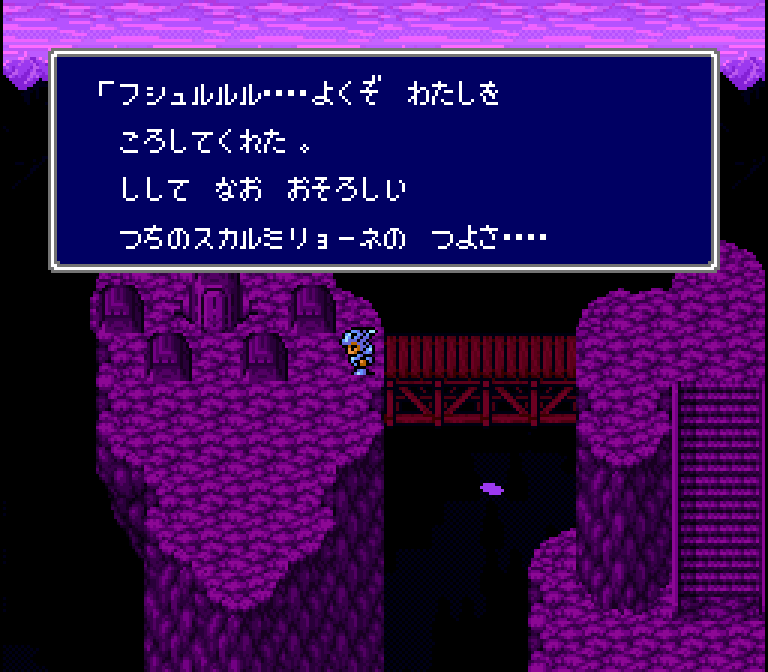

Also, you know how some bad guys are so powerful and confident that they don’t even need to act powerful or confident? Watashi is sometimes used to convey that feeling too:

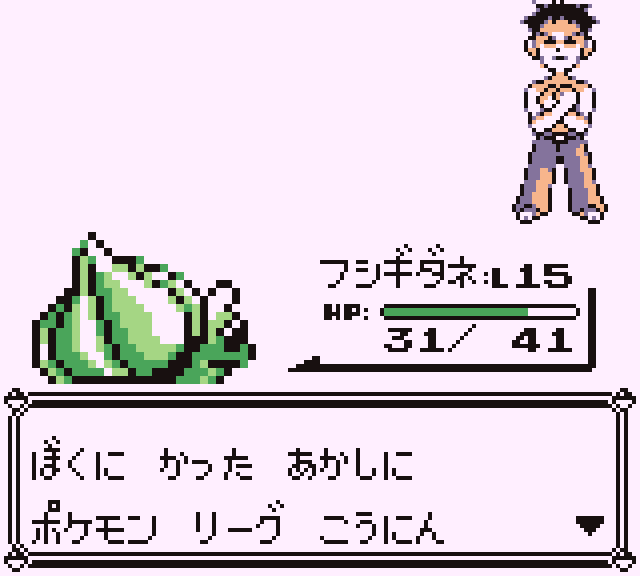

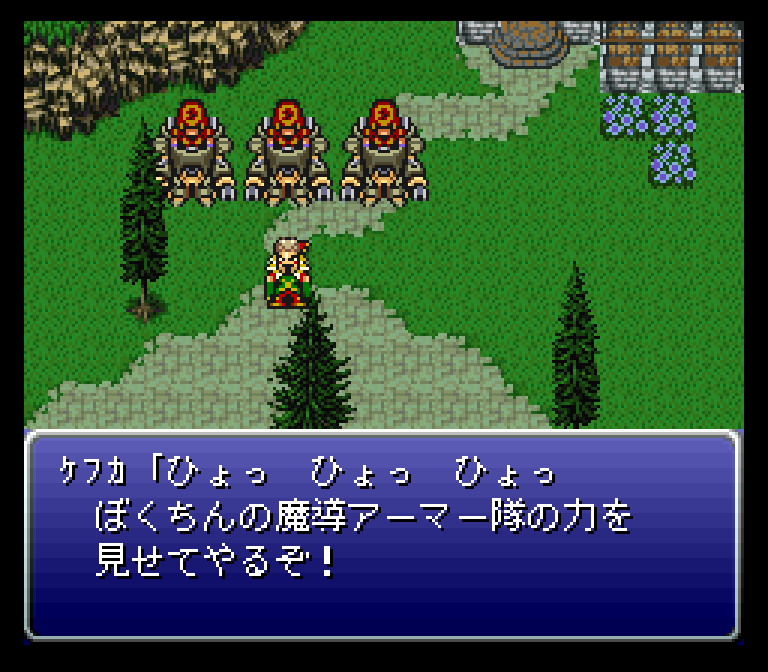

Boku

Boku is an informal, masculine pronoun for “I/me”. It doesn’t carry a strong, sharp sense of manliness, though. Instead, it gives off a slightly softer masculine vibe that’s hard to describe with one word.

Boku can also give off the sense of boyish-ness, gentleness, timidness, decency, and/or being spoiled, among other things.

Note that girls can sometimes use boku too – doing so generally gives them a “tomboy” feeling.

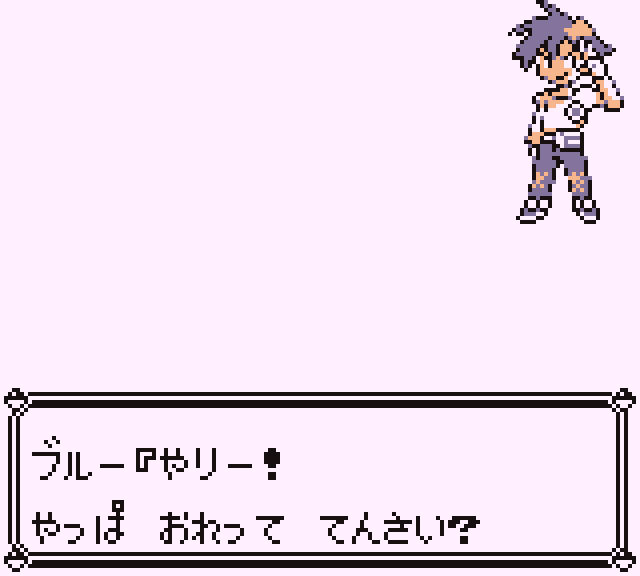

Ore

Ore is another common male pronoun in Japanese. It projects a much stronger, harsher, and manlier feeling than boku. As such, it’s considered a bit crude, and isn’t fit for formal situations or when trying to be polite.

Ore can lend a person a sense of masculinity, strength, confidence, being in charge, and/or vulgarness. Among close friends and family, ore can instead indicate familiarity.

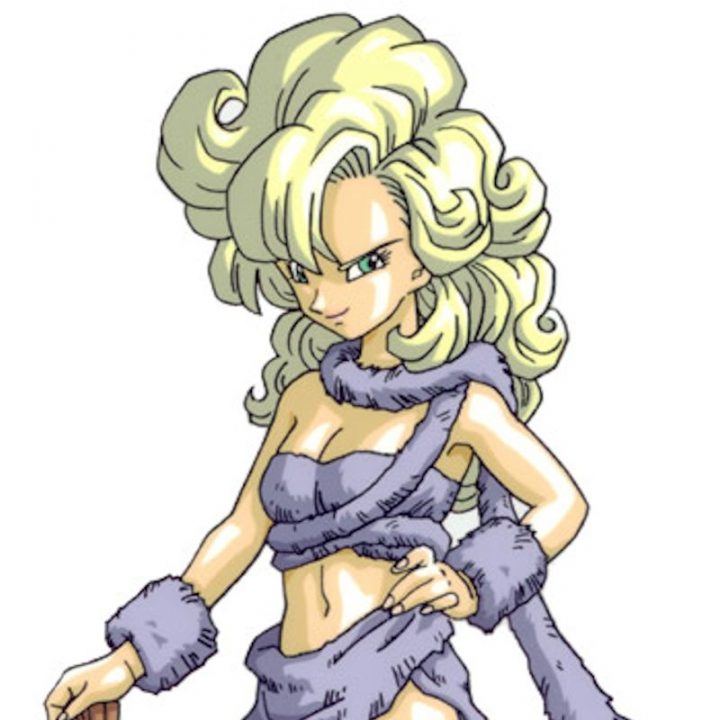

Ore is primarily a male pronoun, but female characters use it on occasion too. Usually this makes them sound tough, manly, and intimidating:

Secondary / Entertainment Pronouns

The above Japanese pronouns are ones you’ll encounter all the time in real life situations and in entertainment.

This next batch of pronouns is a bit different – some pronouns are regional, some are falling out of style, and some are almost completely limited to entertainment these days. But if you spend enough time with Japanese entertainment, these are personal pronouns you will encounter sooner or later.

(Your Own Name, Title, or Relationship)

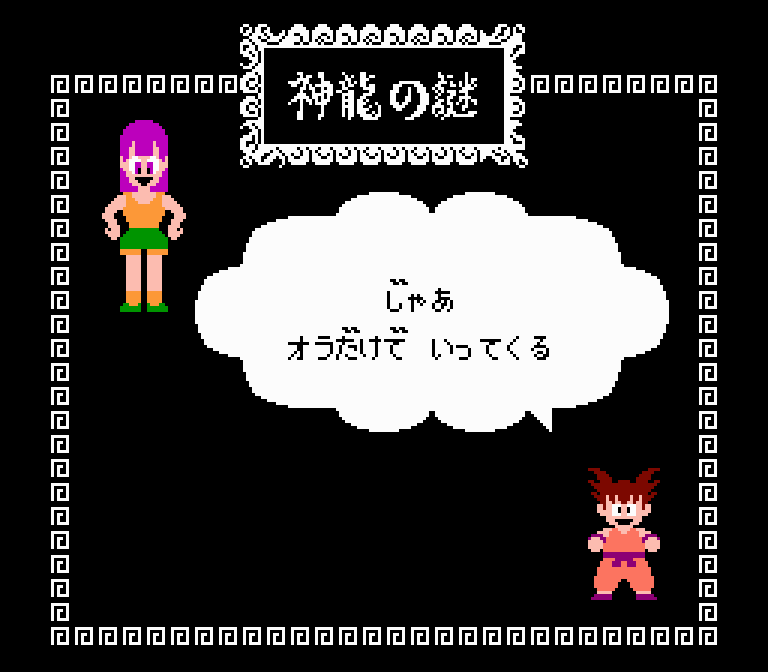

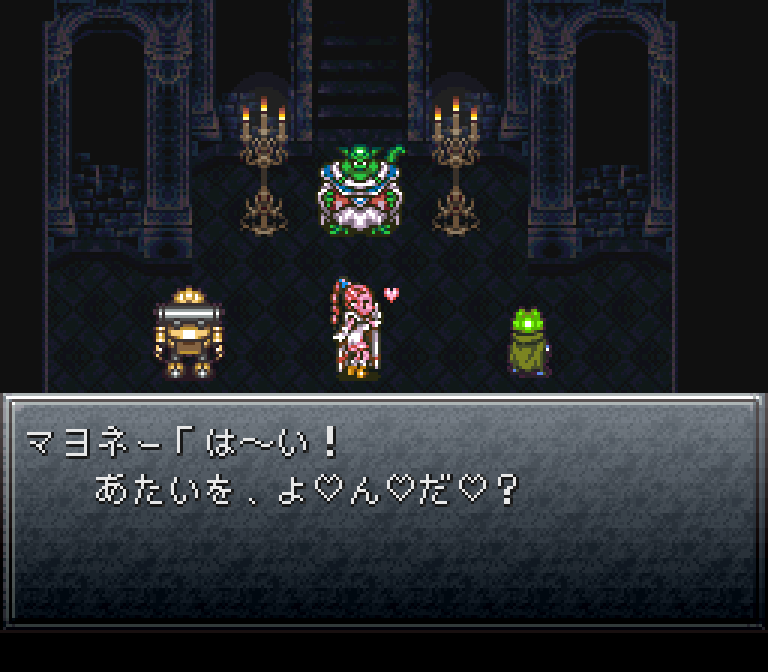

It’s common in Japanese entertainment for characters to simply say their own name instead of using a pronoun for “I” or “me”. Speaking about yourself in the third-person isn’t a Japanese-only thing, of course, but it’s far more common in Japanese entertainment than in English.

When a character uses their own name instead of a pronoun in Japanese, it tends to make them sound innocent, childish, and/or simple-minded. This speaking style is also strongly associated with young girl characters.

Characters who grew up in the wild, characters who aren’t accustomed to human speech, characters who don’t speak the local language, and other similar characters can also use their own name instead of pronouns. This matches with what we have in English, like with cavemen and Tarzan.

Washi

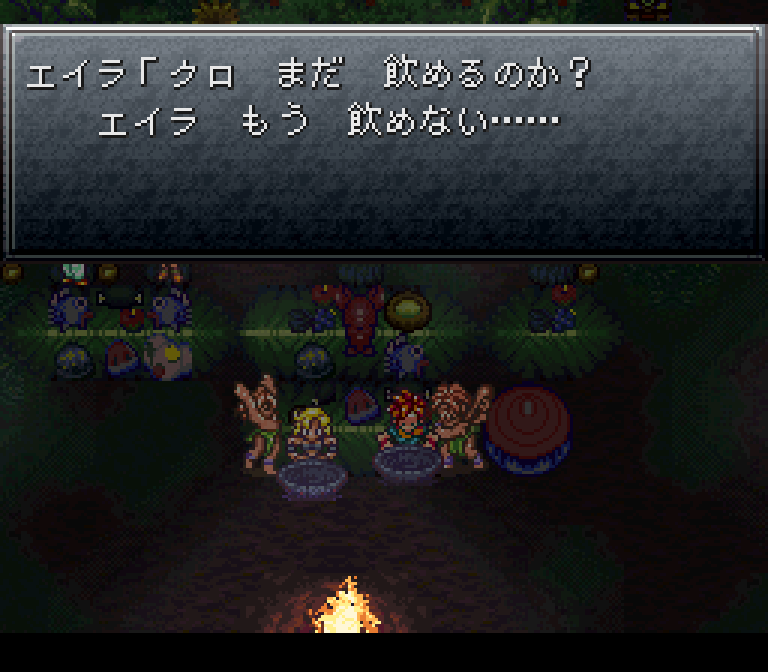

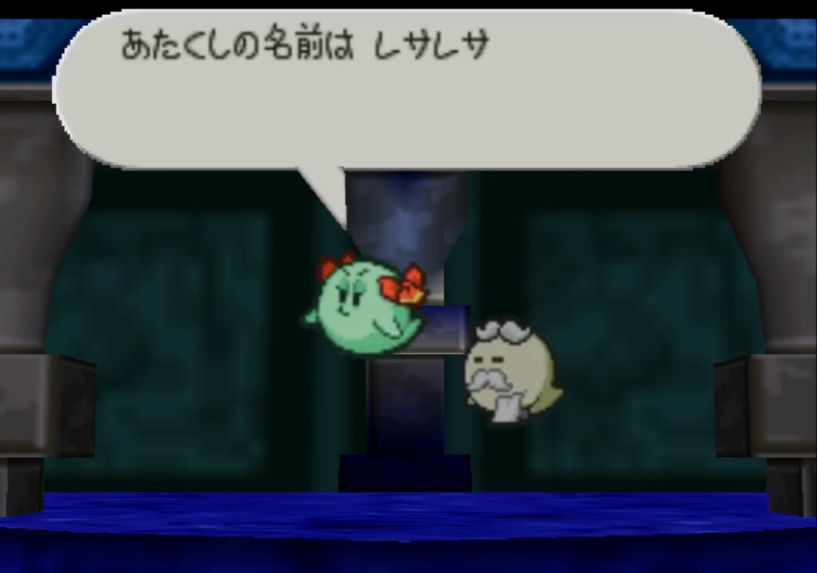

Old people in Japanese entertainment often use washi to refer to themselves. It’s usually used by old men, but not always. Washi is extremely common in Japanese entertainment, but not as common in everyday Japanese.

Washi is also somewhat associated with the Hiroshima region, parts of western Japan, and sumo wrestlers. Supposedly Steven Seagal uses washi when speaking Japanese.

Atashi

Atashi is a more casual and more feminine variation of watashi. It’s very common in both everyday Japanese and in entertainment Japanese.

Watakushi

Watakushi is a more formal version of watashi, and is common in both everyday Japanese and in entertainment Japanese.

Watakushi is usually used to express greater politeness and formality than watashi. It gets used all the time during political speeches, press conferences, business deals, and other things of that nature.

In entertainment, using watakushi outside of formal situations can lend a character a “prim and proper” feeling, or the sense of being very cultured. In some cases, this can be used to make a character sound snobby too.

Atakushi

Atakushi is a feminine variation of watakushi. Characters who use atakushi sound like they’re cultured, refined, and belong to high society. Because of this, atakushi can also give off a “snooty rich lady” vibe in some cases.

Uchi

Uchi is a common personal pronoun in everyday Japanese and in entertainment Japanese.

In the real world, uchi is an informal, mostly feminine personal pronoun that’s primarily associated with the Kansai dialect of western Japan.

In entertainment, uchi is often used by young female characters from the Kansai region or by young female characters who feel like they could be from the region, in the case of fictional worlds.

I should really write a dedicated article on the subject someday, but for now, here is a brief overview of how the Kansai region compares to other regions.

If you’re studying Japanese, note that uchi has a few other, slightly different pronoun uses than “I” and “me”. See here for some more details.

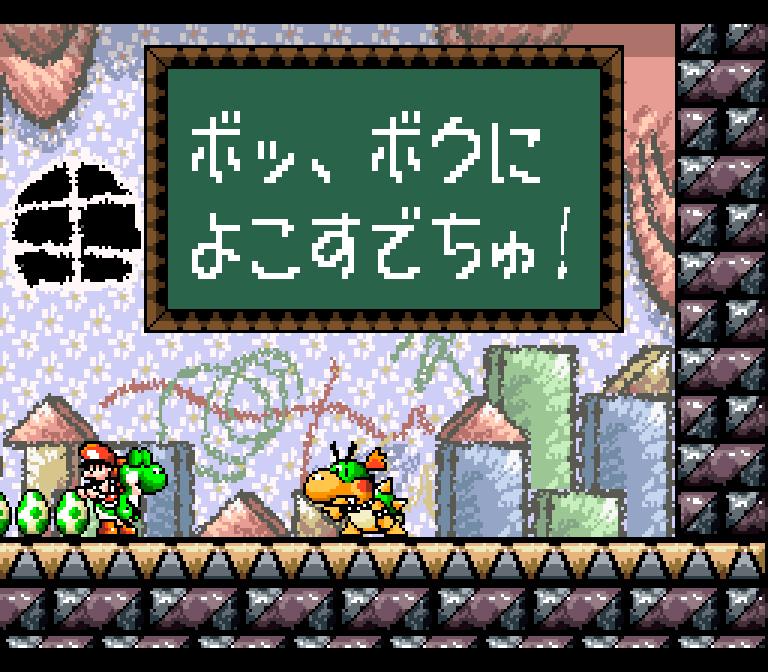

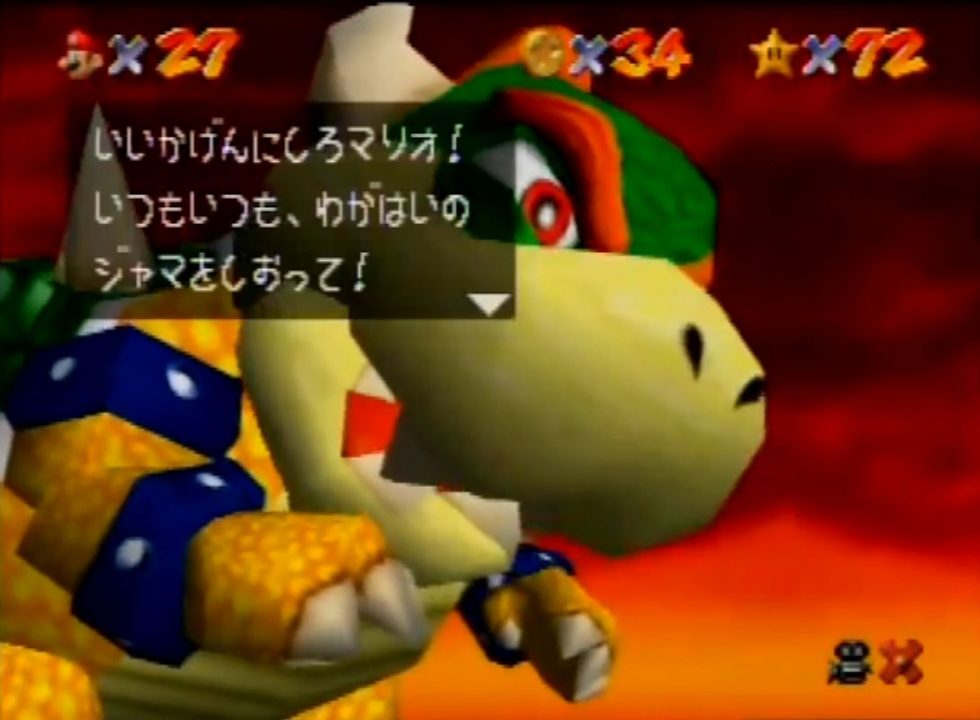

Ore-sama

Ore-sama is like ore, but the added sama makes it more over-the-top.

Ore-sama is pretty much an entertainment-only thing. It’s generally used by male characters who are cocky, egotistical, and think highly of themselves. As a result, ore-sama is often used by bad guys who believe the good guys are no match for them at all.

Ora

Ora tends to give off a feeling that someone is from certain rural regions of Japan or that someone is from a remote area in general. Related to this, ora can also give off a strong “country bumpkin” vibe. Ora mostly appears in entertainment these days.

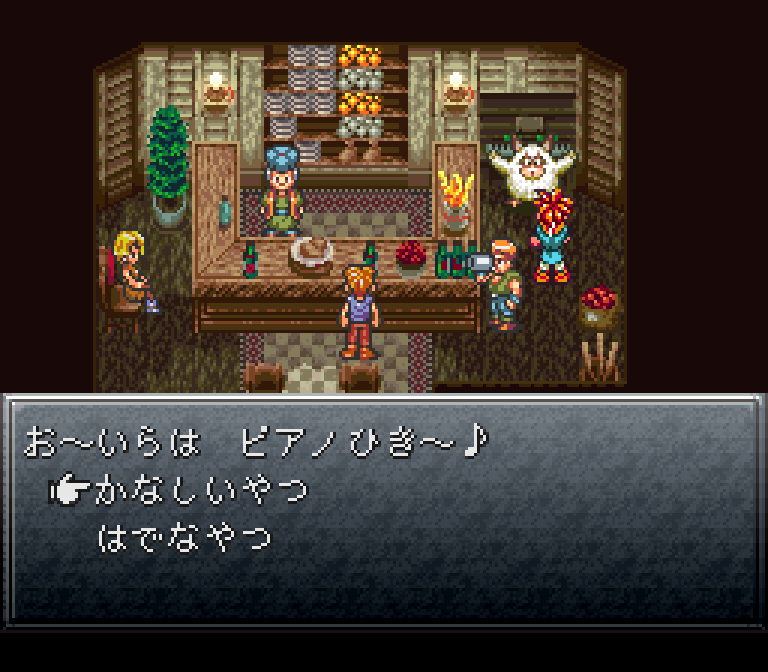

Oira

Oira feels a little less “country bumpkin” than ora. Oira appears quite often in entertainment, but not very often in everyday Japanese anymore.

In modern Japanese entertainment, oira can still be used to lend characters a rural vibe, but more often than not, oira is associated with lovable rascals, rambunctious youngsters, friendly mascots, and other characters of that sort.

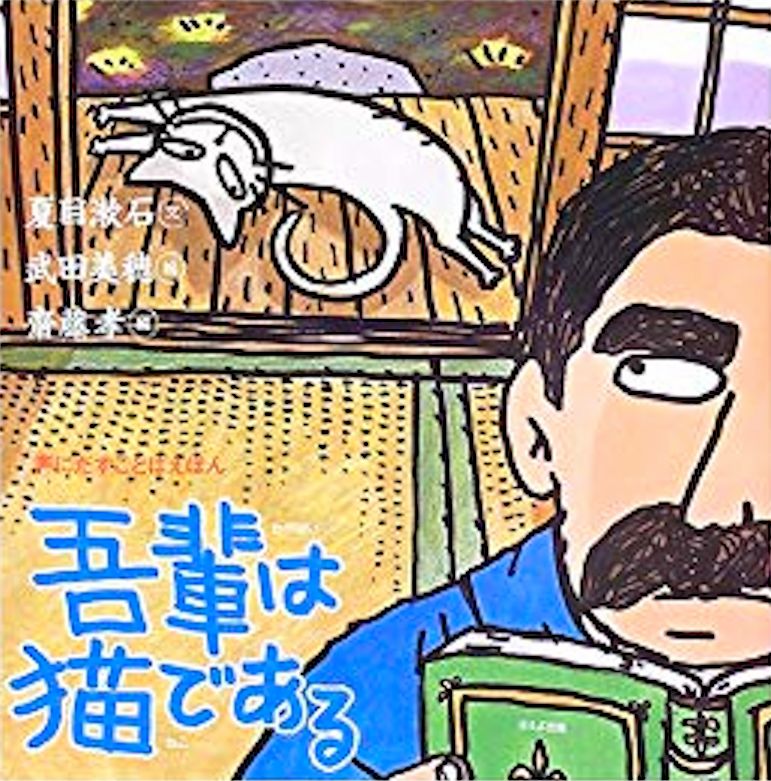

Wagahai

The personal pronoun wagahai gives off a sense of self-importance, arrogance, or the idea of “I’m on a completely different level than you lowly commoners”, like something you’d hear from a snooty nobleman. It’s not really used in modern Japanese anymore, and even feels kind of old-fashioned and outdated.

Wagahai has become very closely associated with the classic book Wagahai wa neko de aru (“I Am a Cat”), by Natsume Sōseki. It’s a satirical look at daily life in Japan in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when traditional Japanese customs began to mix with Western culture. It’s told entirely from the point of a cat who thinks very highly of himself while watching the lowly humans do their silly little things.

“I Am a Cat” is also one of those books that’s taught all the time in literature classes in Japanese schools, which has helped keep wagahai a part of the national consciousness. Because of this tight connection between wagahai and “I Am a Cat”, if you see wagahai in something, there’s a good chance it’s related to the book, to Natsume Sōseki, or to cats in some way.

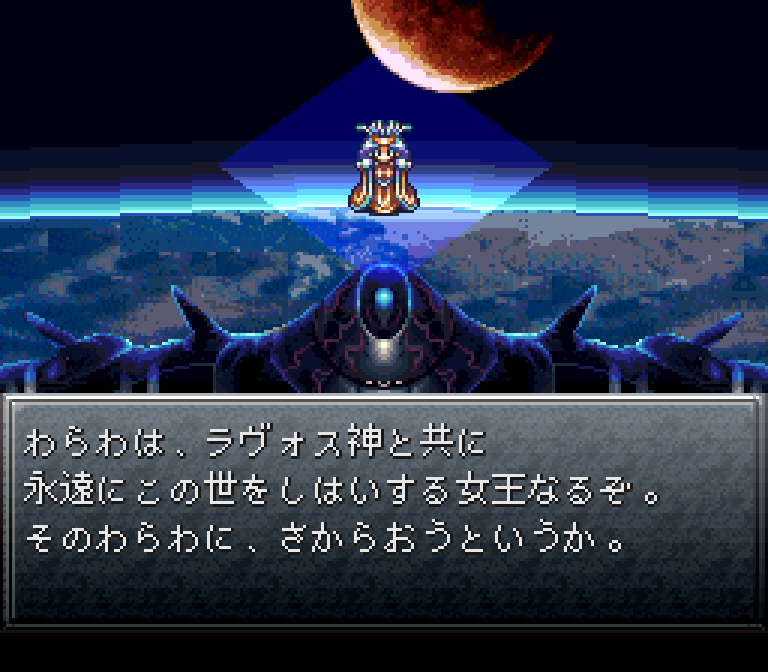

Warawa

Warawa is almost exclusive to Japanese entertainment now, and is usually used by powerful female rulers or noblewomen. This pronoun indicates that a woman considers herself far above everyone else, so it often also carries a condescending vibe.

Yo

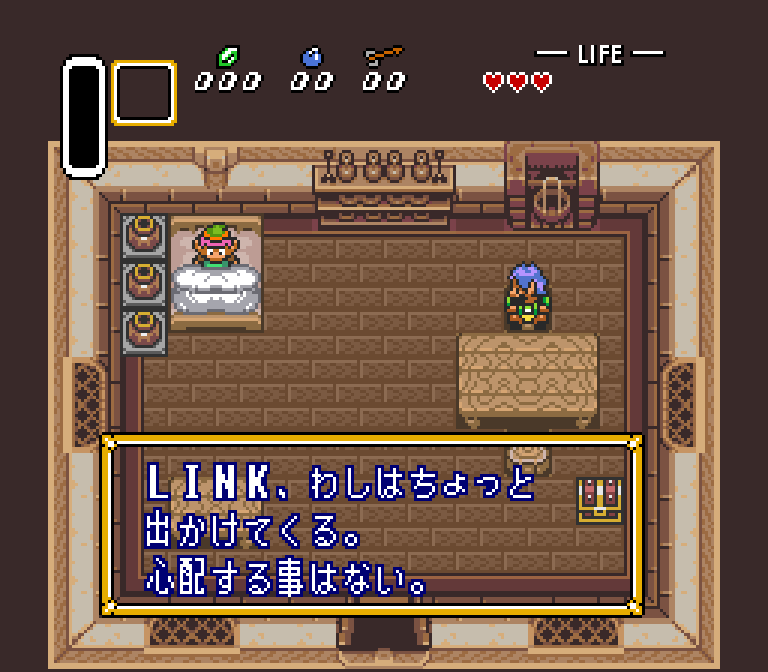

The personal pronoun yo is mostly an entertainment-only thing today. It’s sort of like an old-timey watashi and is usually used by members of royalty or people of high rank.

Yo is often associated with the old samurai times, especially with feudal lords and warriors of high standing.

Atai

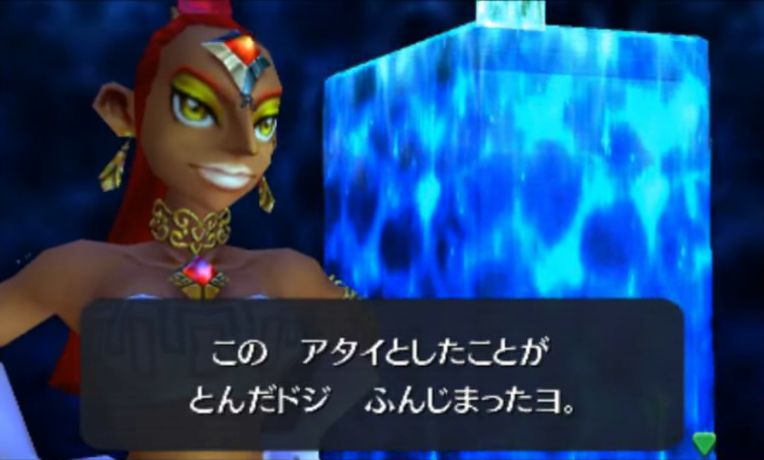

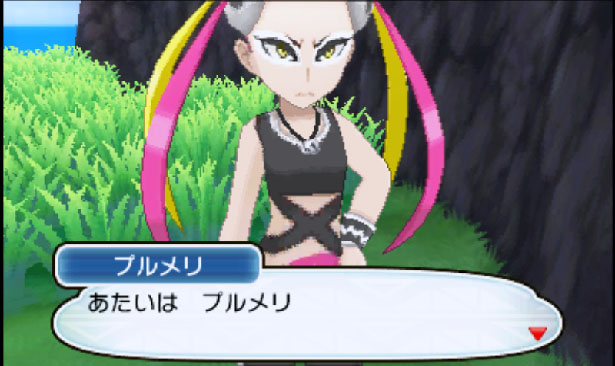

Atai isn’t used much in everyday Japanese these days, but it’s pretty common to see it in Japanese entertainment. Atai is generally used by female characters with rough, brash attitudes. It also gives them a “you don’t wanna mess with me” vibe.

I’ve noticed that some transgender game characters use atai too:

Jibun

The Japanese word jibun usually means “self”, “myself”, “yourself”, “himself”, “herself”, and so on. But jibun is often used as a first-person pronoun too, in both the real world and in entertainment.

Jibun places a clear distinction between the speaker and the listener, so in the real world, someone might use it when talking to a visitor, an instructor, a potential business partner, etc.

Jibun is also heavily associated with organizations that emphasize rank, discipline, and regulations. As such, jibun is commonly used in Japanese entertainment by:

- People who are in the military

- People who are in the police force

- People who are involved in athletics

Some jibun users from Japanese entertainment include:

Mī

The Japanese word mī, which can also be written as mii, comes from the English word “me”.

Mī mostly appears in entertainment and is often used by foreigners or fun, quirky characters.

Wate

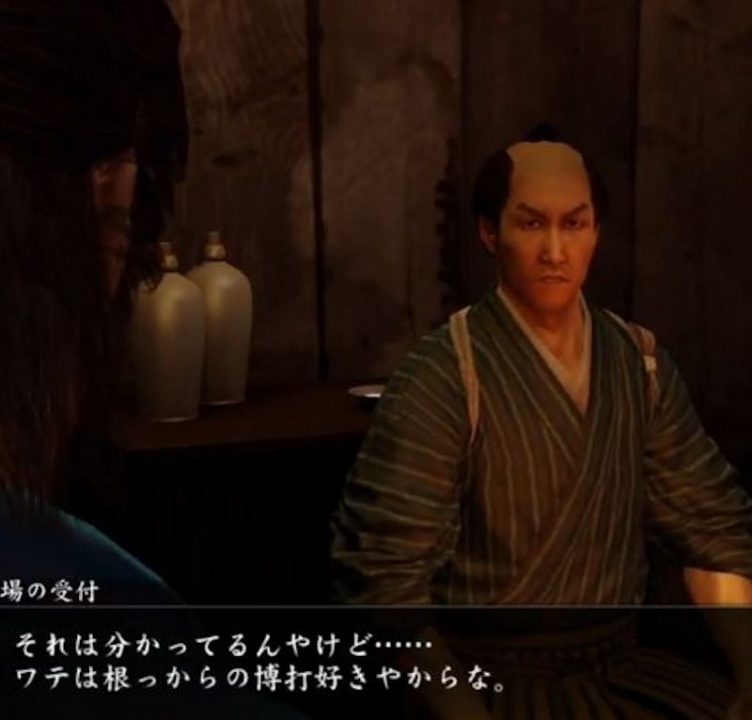

Wate is a regional personal pronoun, mostly used in the western Kansai area of Japan, which includes Osaka and Kyoto. If a character uses wate, they’re probably from the Kansai area or – in the case of a fictional world – act like someone who would belong in the Kansai area.

Wai

Wai is a regional, mostly male personal pronoun associated with the Kansai area of Japan, which includes Osaka. Characters who use wai often also use wate, and vice-versa.

Wai is sometimes used by speakers from northern regions of Japan. In these cases, wai has different nuances and can be gender neutral.

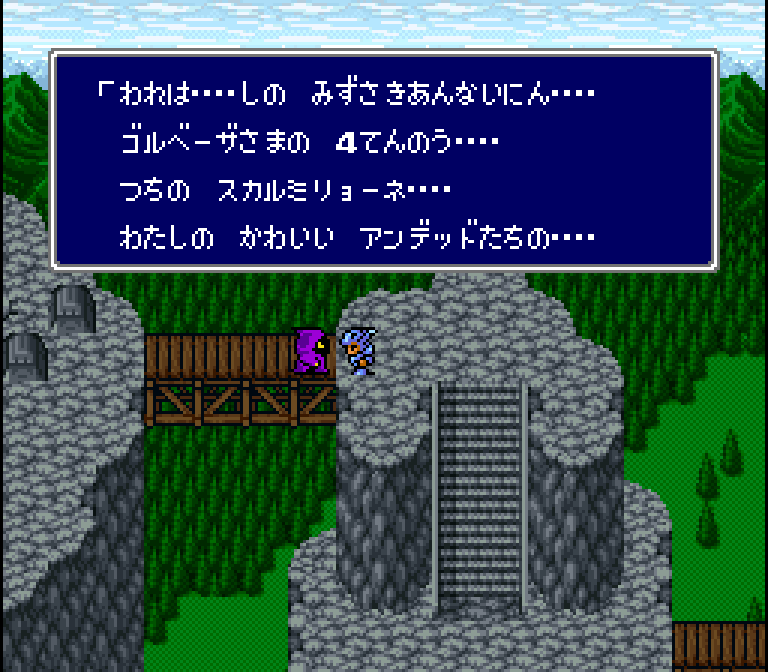

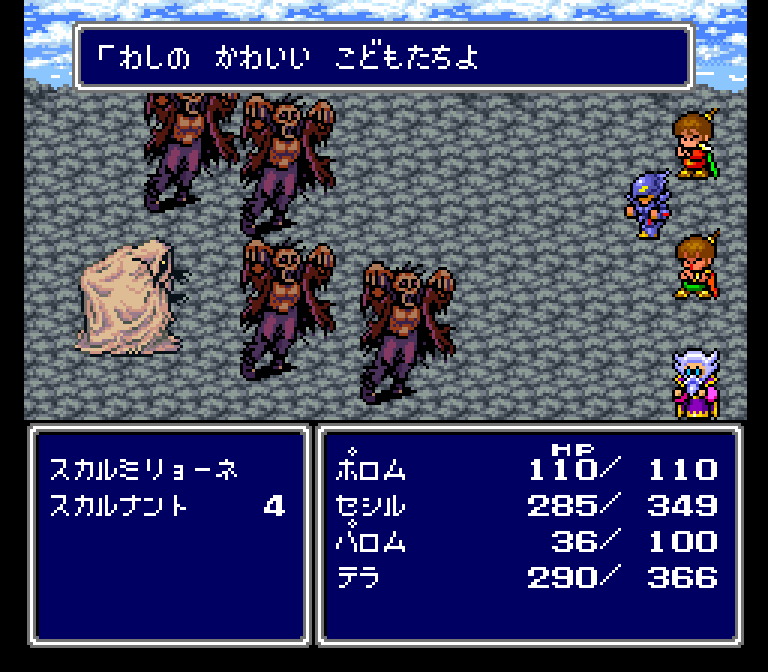

Ware

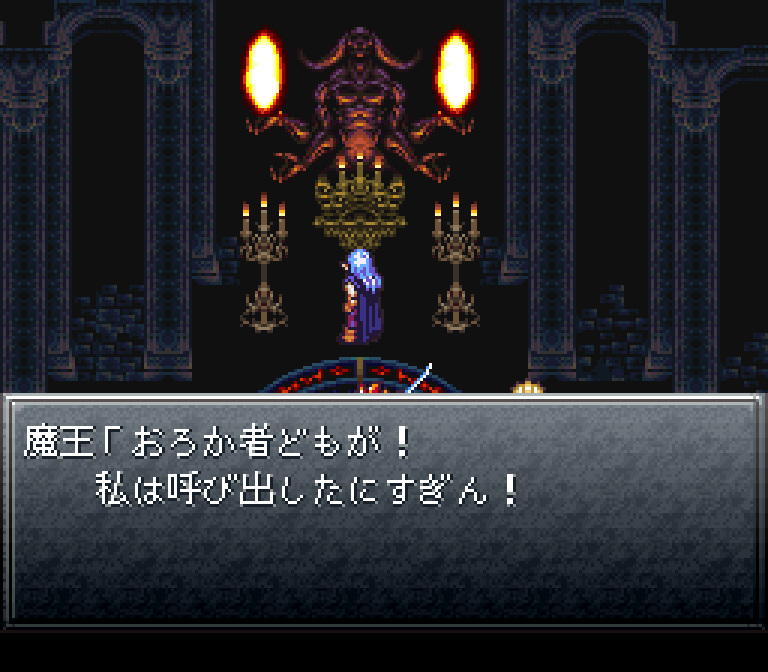

Ware is a personal pronoun that’s seen in old, literary texts. It also pops up from time to time in certain Japanese dialects. It’s a bit unique in that it can mean both “me” and “you” in these dialects, depending on how it’s used. You’re more likely to see ware used in entertainment, though.

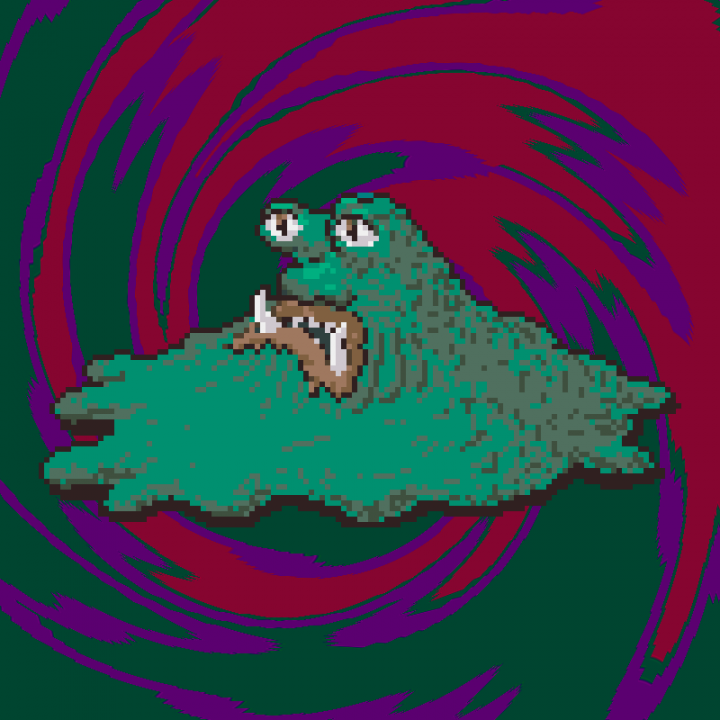

Fictional characters who use ware tend to be old or feel like they’re from old samurai times. Ware can also lend things an “ancient and imposing” feeling, so it’s often used by ancient, powerful beings as well.

Sessha

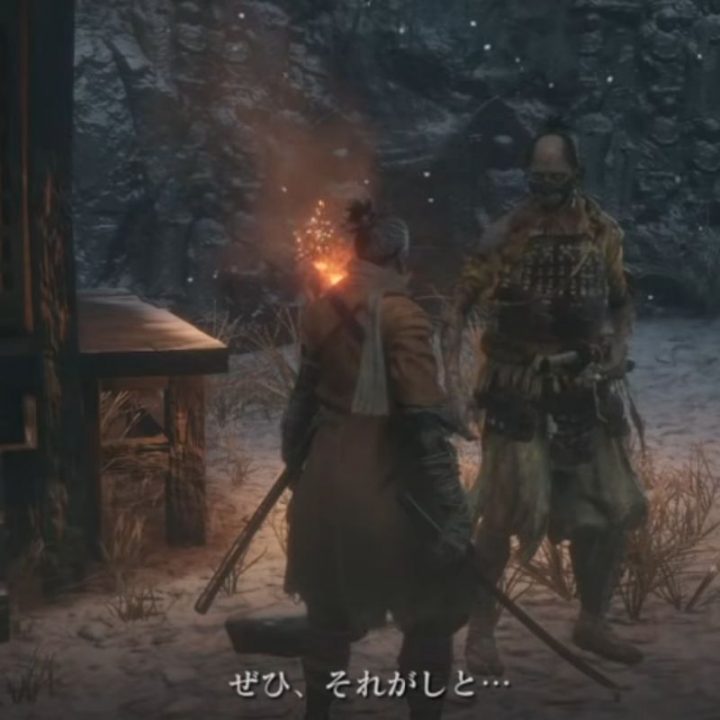

Sessha is pretty much an entertainment-only thing that’s used by samurai characters, ninja characters, and other similar warriors.

Soregashi

As best as I can tell, soregashi is almost indistinguishable from sessha – it’s now an entertainment-only personal pronoun that’s used by old-time samurai-like characters.

For some reason, I feel like soregashi and sessha are best suited for low-tier to mid-tier warriors, while high-ranking warriors would probably use something else on this list.

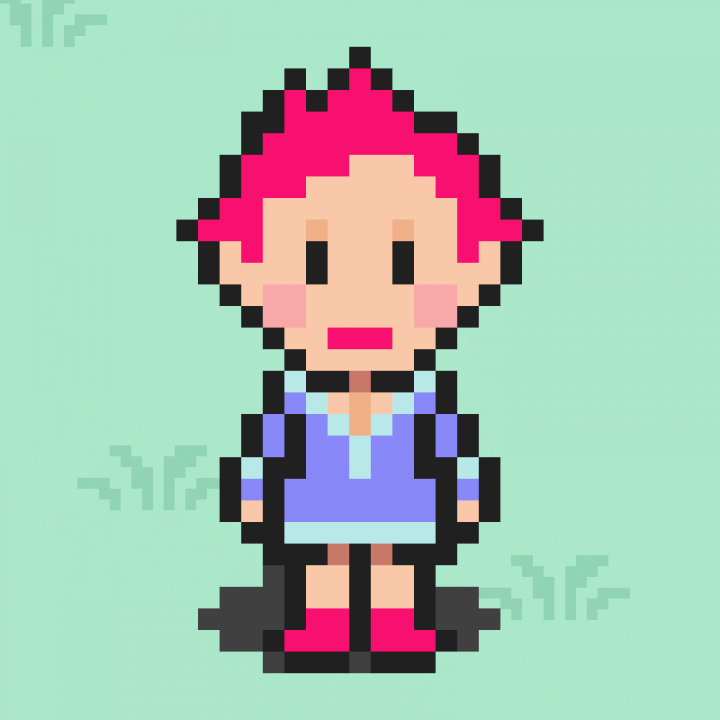

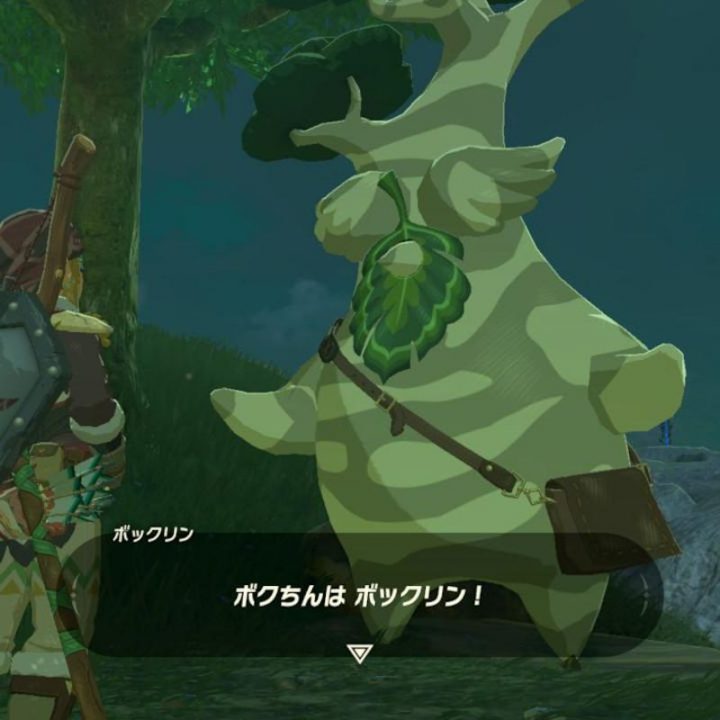

Boku-chin

Boku-chin is a variation of boku. It occasionally appears in entertainment, and only rarely in modern, everyday Japanese. Boku-chin lends the speaker a sort of giddy, childish vibe.

Other Japanese Personal Pronouns

Believe it or not, there are still many more Japanese words for “I” and “me” than what’s listed above.

Unique Creations

Sometimes Japanese pronouns get kind of weird and unique:

Less Common Pronouns

There’s also a whole slew of Japanese personal pronouns that appear in entertainment less frequently than the ones listed above. Here’s a quick and definitely incomplete list:

| Pronoun | Notes |

|---|---|

| ate | Similar to wai and wate |

| boku-chan | Equivalent to boku-chin, can also be used as a second-person pronoun |

| chin | Originates from ancient China, used by emperors, including Japan’s emperor until after World War II |

| fushō | Feels formal and shows humility, suggests speaker still has a lot to learn in comparison to the listener |

| konata | Used by high-ranking warriors, noblemen, and noblewomen |

| maro | Used by high-ranking imperial court officials/aristocrats |

| midomo | Male pronoun used by warriors in samurai stories |

| oi | Male personal pronoun associated with the Kyushu region |

| oidon | Male personal pronoun associated with the Kyushu region, used by older people |

| orecchi | Associated with 19th century stuff, but now associated with the Shizuoka area |

| sessō | Used by Buddhist monks |

| shōsei | Used by academics when writing formally |

| temae | Shows humility as a first-person pronoun, rudeness as a second-person pronoun |

| ura | Regional pronoun associated with central Japan |

| wa | Regional pronoun associated with northern Japan |

| wachiki | Female pronoun, mostly used by geisha and the like in old samurai times. Variations include achiki, achishi, and asshi |

| wadasu | A regional variation of watashi, variants include adasu and wasu |

But Wait, There’s More!

Most of the pronouns we’ve looked at so far are limited to Japanese entertainment these days, but there are many other personal pronouns for other real-world contexts too, such as:

- When talking via radio

- When writing business correspondence

- When speaking as a representative of a specific occupation (police official, religious organization official, military official, etc.)

- When making a formal statement as/for a company or organization

Japanese pronouns are never-ending. Ironically, though, pronouns are used much less often in Japanese than in languages like English.

Important Notes

After covering so many Japanese pronouns, it’s important to keep a few things in mind if you’re learning the language or studying translation.

First, Japanese pronouns aren’t set in stone – people can switch their preferred pronouns as they see fit. In entertainment, this means that if a character normally uses one certain pronoun, they aren’t “locked” into using that pronoun all the time. Again, it’s like clothes – maybe there are some days when you just feel like dressing differently.

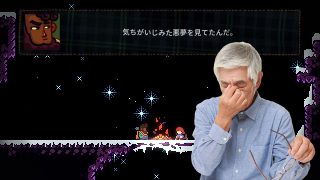

I’m sure I can find a better example, but here’s a game character that demonstrates this pronoun fluidity:

Second, although personal pronouns play a big role in expressing oneself in Japanese, it’s only one character aspect of many. It’s easy for inexperienced translators to fall into the trap of focusing on a character’s chosen pronoun while overlooking other equally important traits. Speech patterns, grammar preferences, particle preferences, mannerisms, direction of thought, tone of voice, and so on are just as important in translation and shouldn’t be overlooked.

Basically, Japanese personal pronouns are important, but are only one piece of the full picture.

In Translation

Personal pronouns can be a big challenge when translating between Japanese and English.

Japanese to English

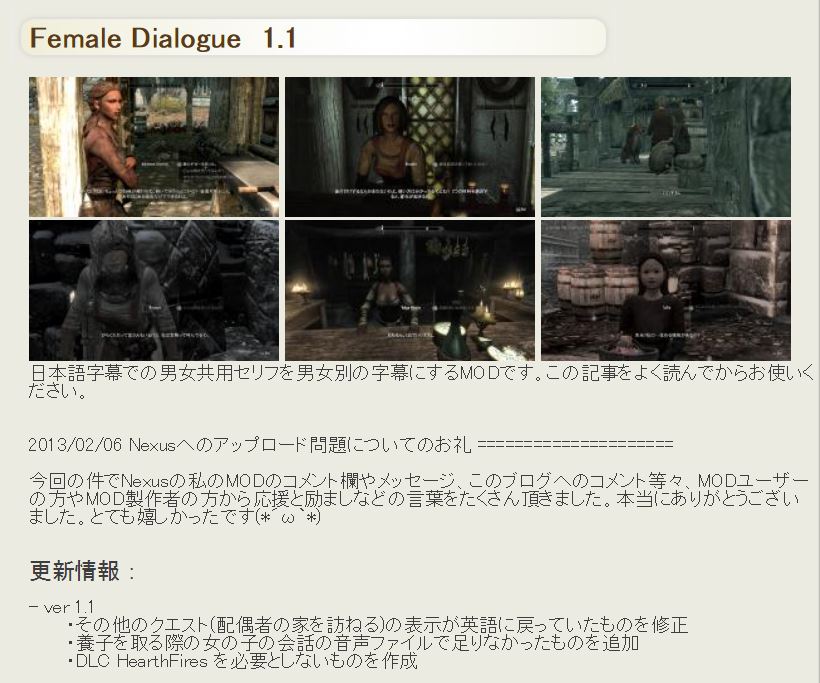

As we’ve seen, the Japanese language has a huge variety of personal pronouns, yet we only have “I” and “me” in English. This means that whenever someone uses a pronoun in Japanese, all of the background details, gender cues, and character traits associated with that pronoun get stripped away in translation. It all just gets “flattened”:

As a result of this pronoun flattening, samurai warriors sound no different from high school girls, ancient monsters sound no different from housewives, and so on. Even the simplest of sentences get flattened down.

This flattening effect can be frustrating for translators. To counteract this, a translator might try to re-inflate a flattened translation by taking all the original text cues and expressing them in a different way in the target language. And, in fact, that’s the very definition of localization.

English to Japanese

If Japanese has dozens of personal pronouns, and English basically only has one, what happens when you translate from English to Japanese? How do you deal with all those “I”s and “me”s?

In an ideal world, a translator will have all the information needed to choose the most appropriate, natural-sounding Japanese pronoun for any given situation. But in the real world, translators rarely have all the information needed. So, when in doubt, the safest choice is to simply use watashi for everything.

Unfortunately, using watashi as a safe default leads to another flattening effect. Again, this leads to giant monsters sounding no different from kindergarten teachers, and ninja masters sounding no different from tax lawyers. These safe translations work, but come off as bland and monotone.

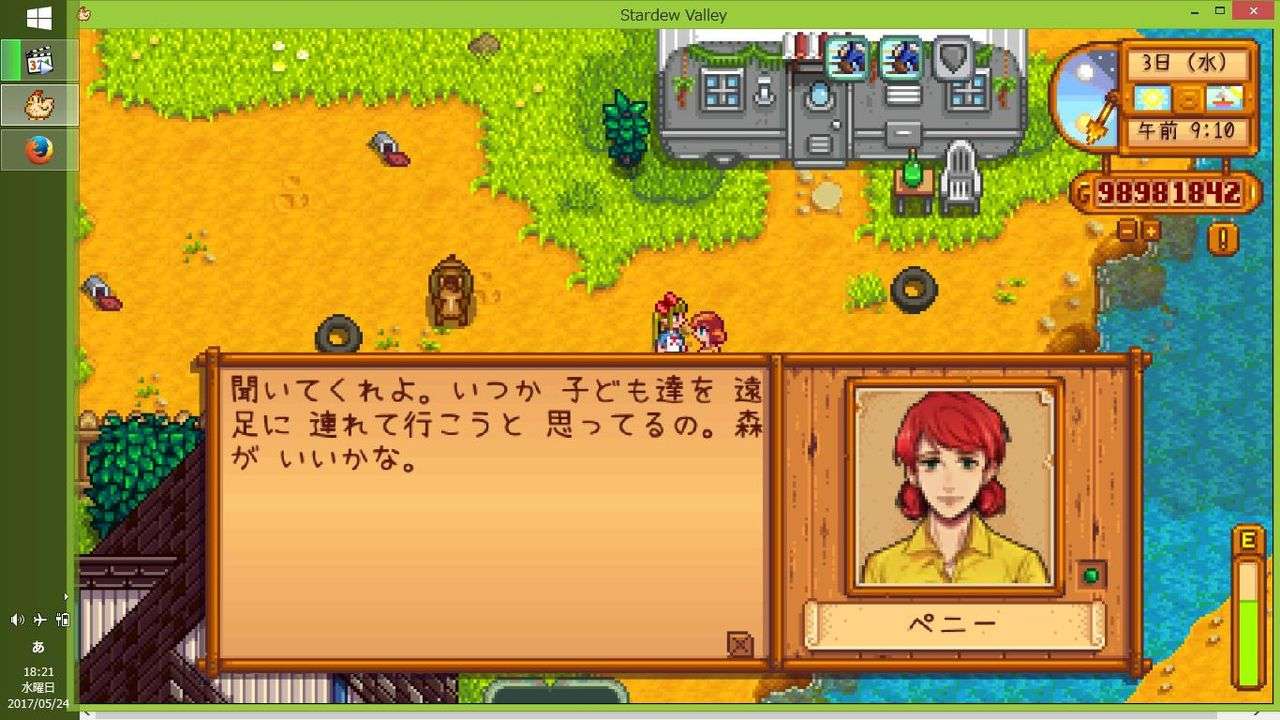

This pronoun problem gets even more complicated when a game has lines of text that are shared by multiple characters. And things get even worse when a game has a character creation system. Basically, unless a developer designs a game with Japanese language peculiarities in mind to begin with, the game’s translation is inevitably going to be full of weird language compromises.

Ideally, an English-to-Japanese translator would have complete notes about who’s saying each line and what kind of character traits they have. Some savvy English-speaking game developers have even started to specify their characters’ Japanese pronouns before getting their games localized.

Final Thoughts

Japanese pronouns – especially personal pronouns – always intimidated me when I first started studying translation. I ran into new pronouns so often that it almost felt like there was some giant, secret list of pronouns that everyone knew about but me. I kept that feeling firmly in mind as I put this article together, so hopefully this simplified overview will help others who are in that same boat right now.

Despite how long this article seems, we’ve only just scratched the surface of how tricky the Japanese language can be to translate. Personal pronouns are just one small piece in the puzzle, so I hope to cover some more tricky pieces in future articles.

For now, if you know of any other characters with interesting Japanese pronouns, let me know. I’m sure I missed some great examples that deserve to be on here!

If you liked this article and know someone in the game industry who'd like it, let them know about it! Most of this stuff isn't widely known outside Japan, so I partially wrote this to help devs understand the challenge of English-to-Japanese game translation.

Two fun examples from Pokémon:

-in the second movie, the collector Jirarudan introduces himself as “watashi wa collector”, while his image song is “Ware Wa Collector”. Gives an interesting idea of how he thinks of himself versus how he reflects himself to the outside…even though he’s quite open with his thoughts and superiority complex.

-In Sun and Moon, Skull boss Guzma, a reckless young man who thrives off of threats and inspiring fear, calls himself “ore-sama” as one would expect, so the translators came up with a novel way to translate the overly familiar and casual tone of it as “it’s ya boy Guzma”.

If anyone reading this article is curious about what pronoun Quina uses in FF9, if I remember correctly, it’s watashi.

That’s funny. It’s so… standard. I would have thought it would have used something like oira or even boku-chin.

Isn’t Quina’s entire shtick their ambiguous gender? Boku-chin and oira are masculine pronouns that would make them come off as less ambiguously gendered.

This is only tangentially related to the topic, but is there any reason Japanese songs almost exclusively use ぼく and きみ for pronouns? Maybe that’s a bit of an exaggeration, but it seems like even if the singer is female or the song is written from a female perspective, ぼく is used. Is it just because it’s easier to fit 2-character words into a meter?

俺 / お前 and わたし / あなた are also commonly used, but 俺 / お前 is closely tied to a male perspective, and わたし / あなた sounds a bit too polite or respectful or remote. ぼく /きみ is chosen as the most gender-neutral yet intimate pronouns of the three. In songs it’s perfectly fine for a female character to use ぼく. It hints that the character is young, but gives no tomboy-ish feeling at all.

I’ve heard that pronouns in songs are generally chosen to fit the meter of the song and don’t really reflect on the singer’s personality beyond that. There are a lot of examples of anime idol characters who use a certain pronoun in speech and then different ones when singing. In Love Live for example, you have characters that use watashi, watakushi, atashi, uchi, ora, and their given name, but the songs pretty much arbitrarily use watashi or boku regardless of who’s singing.

Enka songs’ lyrics almost exclusively use お前 or あんた and 俺.

I googled 60s top hit chart, but 俺, 君, あなた, 僕, and 私 are used. あなた is most popular, and 僕 is least popular.

Apparently it caused a bit of a stir within Sonic Team when it was decided that Shadow the Hedgehog would use the “boku” pronoun: http://sonic.sega.jp/SonicChannelOld/creators/006/003.html

Hey, we don’t JUST have “I”! We also have “we,” if you happen to be some form of royalty.

To digress, the I Am a Cat thing really gave me an epiphany, because I’ve been playing through 428 Shibuya Scramble, and “As you can see, I am a cat” is kind of a catch phrase of one of the characters. I already liked the way it was written, but knowing it is actually (probably, not that I’ve checked the original) a clever literary reference really deepens it to masterwork levels. Although, Tama isn’t much of a wagahai person.

My mind went to exactly that same place too. It feels like it would fit the cadence like a puzzle piece.

True though, Tama doesn’t seem all that haughty. But perhaps she code switches here and there, say when speaking “in character”. Would have to see the original Japanese.

IIRC, the King of All Cosmos uses “we” (capitalized, even). Seems like a good translation of his kingly pronouns in Japanese.

Don’t forget “one”.

“we only have “I” and “me” in English”

Don’t forget “bunself”.

So a while back I picked up the Japanese translation for Star Control 2: The Ur-Quan Masters, and it had a Japanese dub to go along with the translated text. While listening through the files, the number one thing I noticed was the prevalence of “wareware” as a pronoun. Is that a collective version of ware? I remember hearing somewhere that the Japanese translation lost a lot of the humor of the original English version…

Grammatically, yes. But wareware is nearly as neutral and polite as watashi. Along with watashi-tachi, it’s the go-to word for “we” in formal situations.

Here’s something that shows how characters are often defined by pronoun in Japanese media. In Fire Emblem games with Avatars, the different voice options have labels like “Boku 1”, “Ore 1”, “Watakushi 1”, etc in the Japanese version. (And they slightly re-write the dialogue too, selecting “Ore” results in a rougher speaking style)

Most of these pronouns get localizaed through other aspects of the character’s speech, “Ore” characters will use colloquialisms and contractions like “aint” or “gonna” and might be more prone to swearing, while “Watashi” characters will talk more politely. Though some pronouns do have common localizaed equivalents: regal pronouns like “Yo” nearly always become the “royal ‘we’ “, which I feel works well. (The King of All the Cosmos does that too)

One pronoun you missed is “Sessou”, which is similar to the samurai/ninja pronouns in that it’s used by one specific group, in this case priests. This often gets translated as “This humble servant of [insert deity here]” or similar.

I really wouldn’t have guessed Chie used “Atashi” in the Japanese version. I feel like the localizations might have played-up her tomboyishness a bit.

Deciding what pronoun to have a character use in an English to Japanese translation is a really interesting topic to me. For university homework I once had to do an E > J for the voice-over for some multimedia art exhibit where the voices were fairies or other fantastical beings, and I had them use “ware” to try and capture the “ancient, mystical being” feel but my teacher marked me down for it.

On top of all this, there’s the myriad ways of saying “you” as well. One interesting example I found of that in the Ace Attorney Investigations 2 fan translation was that Edgeworth normally uses polite forms of “you”, but switches to “kisama” the moment he suspects someone of a crime. “Kisama” often gets translated as swearing but that’s not entirely accurate, it’s just a disrespectful pronoun. The way I interpreted this was that Edgeworth does not tolerate criminal behaviour and when he uses it it’s a sign of him switching to “serious mode”, and the witness had better be afraid.

sessō does appear in this article, under the heading “Less Common Pronouns”.

Sorry for replying a year later, but atashi is actually the usual pronoun choice for tomboys

“which is about Jesus and Buddha living as roommates”

wait, what?!

It’s a fairly light, sit-com style work, it’s too bad the premise scares away the author from considering releasing it in places like the US.

I don’t know why because it’s quite popular in the US. We shouldn’t be hung up over what people with no senses of humor would say.

Ah, I came across this again so I feel I should update you. It got a US release shortly after this original exchange.

I seem to remember hearing something about this stuff recently with the series One Piece. The most recent arc has a lot of Samurai characters, and on The One Piece Podcast, the manga’s translator talked about how they used old-timey pronouns in the original Japanese version. The way he adapted it into English was by having them say “this one”, as well as a lot of other old fashioned vocabulary. Iirc, he kinda compared it to the series Ruroni Kenshin, and said that that series used a similar style with its titular character.

僕女 are adorable.

Princess Zelda doesn’t *exclusively* use watashi – in Hyrule Warriors at least, and also I think Twilight Princess.

She uses watakushi! Gah, forgetting the most important part.

> the apostle John regularly uses kono shu ni ai sareta deshi (“this beloved apostle of the Lord”) instead of an ordinary pronoun

The Gospel of John in the New Testament occasionally mentions “the disciple whom Jesus loved”, and then at the end says that the whole book is based on the testimony of that disciple, so we conclude that the phrase is John referring to himself. Wikipedia has a writeup, of course: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disciple_whom_Jesus_loved

Presumably John did this because there was some literary convention at the time about not using personal pronouns — for example, the Gospel of Mark mentions a young man running away naked at the Crucifixion that nobody else mentions, which is presumably Mark himself — but it’s pretty funny to imagine John just being a fan of awkwardly long pronoun-phrases.

A common belief is that it’s (also?) indicative of John being the only disciple who both wrote a gospel and truly understood just how much the Lord loves His people, especially considering that the love of God is a bit of a running theme in John’s books, and that his gospel focuses on Jesus’ compassion and love more than the other three. (And, y’know, it’s where we got John 3:16 from, which is a pretty famous verse!)

Mark, meanwhile, seems to have mentioned the young man as a subtle “I was there, too”, which makes sense because his primary source is widely believed to be Peter. He might’ve been showing humility by not putting himself on the same level as the disciples, he might’ve been trying to downplay his own presence so people wouldn’t think he was deviating from Peter’s teachings, or maybe he was just plain embarrassed about running away naked. Who knows.

There doesn’t _seem_ to have been a big thing against personal pronouns at the time, at least not in general. Paul wrote his letters during the same time period, and he tended to use personal pronouns a lot; as a Jewish Pharisee and Roman citizen, he was probably one of the most educated Christian writers of the time period (Pharisees had to memorise _the entire body of scripture_, and his family had access to the myriad benefits of Roman citizenship), so he’d have known about such a convention if it existed. And Luke, a doctor and researcher (the former explicitly stated, the latter implied by him creating a detailed report with testimonials from multiple eye-witnesses and performing his own personal investigation), only used first-person plural a small number of times in Acts. Meanwhile, John used first-person and first-person plural in his letters, which contrasts with his “the disciple Jesus loved” third-person in his gospel.

Overall, it may have just been that different types of documents were written from different perspectives. Letters were written as personal literature, and tended to use first-person. Meanwhile, reports and documentaries might have only used first-person if the writer specifically wanted to draw attention to their participation in the documented events, something that’s still frowned on even today; maintaining a clear lack of bias to the best of your abilities is pretty important, after all. I’m not sure if it would’ve been a Jewish thing, a Greek thing, or a combination of the two; considering that a large number of Jews at the time were Hellenized, Greek-speeking Jews, and tended to maintain Jewish writing conventions even when writing in Greek, there’s a lot of room for writing styles to draw from both languages.

In DEATHNOTE, Light(In formal situation, he uses ”watashi”), and Matsda uses “boku”.

L, Near, and Mikami uses “watashi”.

Ryuk, Mello, and Aizawa uses “Ore”.

And more, Misa mainly uses her own name.

I think this is good example.

“If you’re an alien, why do you sound like you’re from Kansai?”

“Lots of planets have a Kansai!”

Also, by “some Pokémon spinoff games”, do you mean Pokémon Super Mystery Dungeon?

*Looks at list of characters using “Atai”*

What, no Cirno from Touhou Project, the strongest fairy? XD

More seriously, the Professor and Assistant from the Kemono Friends anime use “wareware”.

I presume it’s a plural form of ware?

Anyway, the Professor and Assistan are basically the biggest autority figure in the Kemono Friends anime

and the protagonist first purpose is to meet the to learn what she is.

I always wondered why they don’t just keep it simple instead of making up countless pronouns for different types and ranks of people speaking, but I learned to gradually accept it for what it is. It still makes things complicated during translation and localization though.

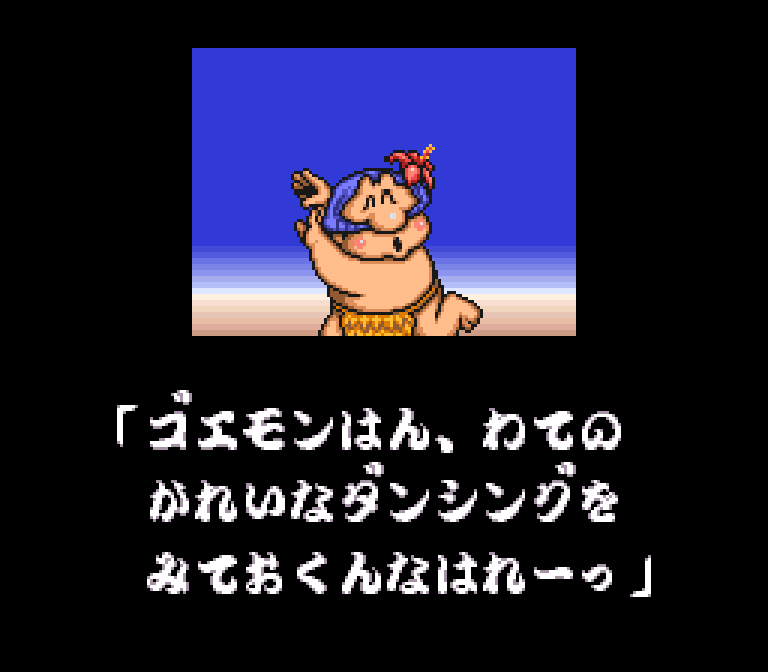

However, I must note that I absolutely love Ebisumaru’s strange Kansai accent in any voiced Goemon media. He’s so hilarious whenever he opens his mouth. Tentomon from Digimon also speaks with a Kansai accent in Japanese (which sets him apart from the other Rookie Digimon), though I tend to watch that series in English.

To native speakers and readers, these pronouns serve the exact purpose of “keeping it simple” (among other purposes). A reader can learn a substantial amount from text alone about, say, the personal outlook of a newly-introduced character through the pronouns they use in Japanese scripts. The “feel” of a character can be established simply and quickly.

The difficulty of conveying the same meaning in English and the variety of approaches used to approximate it in translation, including stuff like translators assigning what they perceive as roughly equivalent regional English dialects to characters, give some idea of how some aspects of English are hard to “keep simple” in the same way.

After all, it’s not like these Japanese pronouns were “made up” by contemporary speakers for the purpose of reflecting contemporary social relationships. Like nearly every aspect of any language, they reflect the historical development of that language over time in different places and for different purposes. The nuances they’ve acquired reflect that.

Speaking of picking your personal pronoun to fit the occasion, Mouri Kogoro from Detective Conan almost always uses ore, even ore-sama at times, but then whenever he tries to get some charming lady’s attention he’s a watashi-guy all of a sudden.

I’m a big fan of “wareware” because it sounds so amusing every time I hear it! 😀

A fun example of a good localization is Katamari Damacy’s King of all Cosmos using the royal “We” as a pronoun in place of “King”, gives the same effect but for an English audience. Nothing too special but something I noticed to myself while reading the article.

Agness Kaku, localizer of Katamari Damacy, mentions this in a 2011 interview.

https://web.archive.org/web/20140316150958/http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/metalgear/agnesskaku3.htm#17

“You know the King speaks in a royal ‘we’ all the time? That was something I decided to do with the first one, because it felt right. It’s also lovely because it saves on a lot of characters, instead of referring to himself as, I dunno, ‘I the great’, or whatever.”

>The Japanese version of Meowth used oira early on in the Pokémon series

No, he’s always used “Nyaa” as his personal pronoun. “Oira” is exclusively used in his character songs. I have NO idea why this is, maybe the the writer of his first song didn’t get the note and the others are just referencing it?

The image songs must do this. I listed another example too.

Thanks! And dang, I think Meowth was the first time I encountered oira too, I’ve been living a lie all this time

“Nyaa” is not a word that originally means “I”. It is originally a “cat’s Meow”. In Japanese, Cats will be “Nyaa”.

The Pokemon animation uses “Nyaa” as an “I” for cats.

I remember Zankuro from Samurai Shodown also being a big user of “ware.” Mostly because he tended to tear me apart a lot.

I’ve heard in the Japanese dub of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, the tomboy Rainbow Dash uses “boku”. I’m guessing Applejack (rough and tumble farm girl) says “uchi”, while Rarity (self-styled “lady”) uses “watakushi” or “atakushi”.

Mumbo Jumbo in the original English speaks in the third person, or more specifically says “Mumbo” in place of a personal pronoun. Is this reflected at all in the Japanese versions?

I did some researching of the MLP Japanese dub, and found Princess Luna uses warawa instead of we for her “Royal Canterlot Voice”:

https://youtu.be/Njx3Oz31Fjc

Of the main cast:

Twilight and Fluttershy use “watashi.”

Applejack and Pinkie Pie use “atashi.”

Rarity uses “watashi” sometimes and “watakushi” other times, depending on how high her opinion of herself is at the moment.

Rainbow Dash and Spike use “boku.”

Not that I know much about the language but I know my favorite ware is Zengar Zombolt/Sänger Zonvolt/ゼンガー・ゾンボルト and his giant sword

Sanger tends to use ore in normal speech, but uses ware in his famous catchphrase. Basically, he switches when he’s acting like more of a samurai.

There are two examples from Guilty Gear XX that have stuck in my brain; one of them is Johnny, who uses “Ore-sama”, which is very appropriate for him. The other one is Zappa (my favorite character), who uses “Ore”. That seems weird to me, given his characterization; when he’s not being possessed by a vengeful ghost, he comes across as a very polite, almost timid young man. He seems more like the type to use “Boku” or “Watashi”, but maybe there are some nuances there that I’m missing. Maybe he uses “Ore” as a sort of confidence boost? I don’t know, but I’m really curious as to the reasons behind that choice for him. 😀

I’m Japanese. It is a very wonderful article that clearly states we feel unconsciously.

I use boku and watashi properly. I feel that boku fits my personality.

I have something to tell you. Takeshi Kitano uses oira. He does at least at television shows.

“Oira” gives an idyllic impression.

I am Japanese. This article is very good. I call myself “ore” in a private place, “boku” in SNS, and “watashi” in official places.

In the case of me, “you” usually refers to the other person’s nickname. I rarely use “anata” or “omae”.

Can “omae” be used casually? I was of the impression it was a rude/impolite means of speaking to someone.

Not Japanese, but I’ve heard “rudeness” in Japanese can be better described as “familiarity”. Around the wrong person it has a connotation of disrespect and can come off as an insult–it’s treating someone you’re supposed to be polite to, or heaven forbid a direct superior, like they’re equal or lesser. Around people you’re friends or family with, though, it shows you trust and care about them. (Ness’s and Ninten’s dads in the Mother series use “omae” for their kids, for example.) In that context “omae” would be acceptable to use.

I don’t claim to be an expert on this subject, of course. Not Japanese, remember.

When used in a formal setting, it has literally gotten people fired: https://soranews24.com/2018/10/13/niigata-school-superintendent-resigns-over-incorrect-use-of-japanese-word-for-you/

As he said, it’s a casual and familiar word that you just don’t use in situations where the other person expects formality. If you show up at a funeral in America and offer your condolences by going “Man, shit sucks, huh?” you’re probably going to similarly offend people. Expected levels of politeness and formality isn’t a concept exclusive to Japan.

“Expected levels of politeness and formality isn’t a concept exclusive to Japan.”

I never said it was, but it is decidedly more punishing than in many other places.

Is it really? If, in America, a guy’s son had committed suicide and the school superintendent had come to his house and said “Hey dude, heard your kid killed himself”, I can’t imagine that not being taken as him being horrendously rude. There’s a time and a place for casual speak, and there’s a time and a place where casual speak is outright offensive to use.

It’s rather amusing to see your constant comments defending Japan despite the fact it wasn’t where you were born.

“omae” is an expression of familiarity and at the same time gives the other person the impression of being perceived as having the same status as or less than you. Therefore, it is often a rude word.

Sweet, actual Japanese people seems to be a rarity on this site. I’m sure you could be a great help to Mato and the crew.

I can think of one brief example of a female character using the pronoun “ore-sama” in the first season of Slayers. I forget the episode title, but it’s from the episode in which Lina accidentally unleashes a swarm of ghosts by destroying a mound that’s separating two nearby villages. In the aftermath she winds up becoming possessed by some of the ghosts, which in turn affects her behavior and pattern of speech. At one point she starts speaking in a drunken manner, and during this personality change she refers to herself as “ore-sama.”

In addition, according to this promo for the Japanese version of Adventure Time, it would appear that Jake also uses “ore-sama,” which seems out of character given his personality. But maybe it’s context-sensitive and not how he regularly refers to himself… can’t say for sure.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e9JJV73-URs

I think Freeza’s use of “watashi” is interesting, and moreso a matter of being formal than it being the default. Freeza is, in part, a send up of the Japanese real estate market. He’s literally an evil intergalactic real estate agent, and so while just about everyone else in Dragonball are rude and informal, Freeza tends to be faux polite as if he’s trying to trick you into buying something. Similarly, a lot of his sadistic behaviour involves pretending to do his opponent a favour by going easy when he’s really trying to humiliate and despirit them.

So, you can see how Freeza himself is humiliated when he’s pushed so far as to drop the act.

(You can look at an interview which discusses Freeza’s creation here.

https://www.kanzenshuu.com/translations/daizenshuu-2-akira-toriyama-super-interview/

)

Actually, the Namek saga also introduces some interesting pronoun use by Goku. As mentioned in the article, Goku has mostly used “ora”, as well as having a silly folksy dialect. But when he goes Super Saiyan, he switches to the more standard “ore”, which perhaps is meant to give the sense that playtime is over and it’s serious now. The anime plays this up further by adding a voice change to match.

For ware, it’s interesting to note that it uses the same character as I in Chinese (still in use today in that language.) It likely came into Japanese with all the other kanji and fell out with time.

I was just watching a video of the Jevil fight from Deltarune in Japanese, and I noticed that he switches from “boku” to “washa” at some point during the battle. I wasn’t paying too close attention to the dialogue so maybe there’s even more pronouns he uses? “Washa” must be another unique one, because I couldn’t find it in my dictionaries and I didn’t see it listed here, either. Susie’s also a good example of a tough girl who uses “ore”.

‘Washa’ is a contraction of ‘washi wa’.

“Boku-chin” is perfect for Hetsu, that giant Korok. This makes me want to watch Japanese game streams just to see what pronouns every character uses!

Reading this article, I learned that “ore” in Japanese means “rock containing metal” in English. It is interesting.

The English word ‘ore’ is pronounced identically to the English word ‘or’. Transliterated into Japanese, it would become オー.

A more typical transliteration of the English word “ore” would be オア.

This seems like the perfect opportunity for another Splatoon nerd flex:

Female and male Inklings use “atashi” and “oira” respectively, according to the amiibo boxes. The squid, which is shown to be a boy in Mario Maker, uses “boku” (and speaks in a more polite way than the other two).

Callie uses “uchi,” because she and Marie are implied to be from the future version of the Kansai region, and because she’s a dork (people from the Kansai area have a reputation for being loudmouthed buffoons, a description that fits her perfectly). Marie uses “atashi.” Cap’n Cuttlefish uses “washi” as far as I know.

Pearl uses “atashi,” but has a tendency to speak in a really crude and masculine way, particularly when she’s angry. Probably because of her rapper shtick. It’s an interesting contrast. Marina, who is far less assertive and brash than her sempai, uses “watashi.”

‘Atashi’ is basically the usual choice for crude, masculine-talking women if they’re not given a masculine pronoun. Kind of odd, but hey.

Has there ever been an instance of Waluigi using a pronoun in Japanese text ? I want to know what he would use in comparison to Wario’s “ore-sama”, being the embodiment of self-pity.

According to the Japanese Wikipedia page for Waluigi, he uses “ore” and “ore-sama”.

There are some old man characters that use a melding of washi + wa, with the result being “wassha”. However, the only one I remember off the top of my head using that was the old seed forager from Hokuto No Ken.

Other examples of oira users are Popoi from Secret of Mana (though of course this one’s a unique case since Popoi’s gender is never stated and is referred to as “they” in the remake’s English dub) and Tarosuke from Shadow Land/Yōkai Dōchūki, from when he appeared in Namco x Capcom and Project X Zone 2.

How does having the pronoun written in kanji/hiragana/katakana change the “feel” of the character’s speech? It seems like I see more characters who use “ore” also have it written in katakana nowadays than before.

That’s actually a whole different level of nuance that I was thinking of putting into this article, but it wound up so big already that I figured it would be better to save it for another time. It’s not something I can’t easily give an in-depth answer here but basically, yeah, “boku” in kana is a little softer/younger than “boku” in kanji, “ore” in kana feels a little more youthful than “ore” in kanji, etc.

I hear that sometimes female characters who use “boku” have it written in katakana to emphasize that it’s a little odd for a woman to call herself that. Is that true?

Come to think of it, that could be quite an interesting article indeed. Like, what sort of nuance it gives if a character speaks only in kana? Is it a robot? A dumb muscle for the villain? That sort of thing.

Translation or otherwise, has there ever been an instance of character speech like Strong Mad’s being represented with kana?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q8qnGcLKTdI

That’s pretty weird and unique so I’m not sure. With something that strange, I think it’d be fun to use katakana in place of hiragana and vice-versa, but I dunno how a native speaker would handle it.

Thanks for the reply. It was the best example I could think of the “dumb muscle” bronzeheart92 bought up, since I know for sure katakana has been used to indicate robotic speech.

Native speaker here. I’m also not sure how to fully translate that weird speech but… I might use “ode” (おで, saying “ore” with stuffy nose) to express some dumbness. Yamada from Chibi Maruko-chan is a famous ode-boy.

By the way, robots and non-natives usually speak with inverted hiragana/katakana. Like ワタシ ハ ろぼっと デス。

For an example of an English work flubbing this, there’s Uncanny X-Men #205. In it Wolverine loses his memory (again) and starts speaking Japanese. Problem is Logan’s first words in this are “Boku wa dare?”, which struck me as hilariously out of character for him. No idea what Wolverine uses in translations (俺? 俺様? Something more exotic?), but I kinda doubt it’s 僕.

The Capcom games have him use オレ, the katakana written version of “ore”, throughout all of his Versus appearances. This is coupled with giving him rough speech. Taking one of his victory quotes from X-Men from Street Fighter as an example:

オマエらが相手でも、オレの中の野獣はおさまらねぇのか…

Omaera ga aite demo, ore no naka no yajuu wa osamaranee no ka….

“Y’guys were my opponents, I’m wonderin’ if the beast in me ain’t satisfied yet.”

Notice the usage of “nee” rather than “nai” as well as “omae-ra” (you [damn] guys/you [damn] lot), -ra typically when couple with 2nd person pronouns gives it an even more coarse/masculine edge to it. He also uses the katakana version of “omae” to give just that extra detail.

Juggernaut goes even further in the Versus games with a consistent and constant usage of オレ様 (ore-sama).

This list is so enlightening for someone currently learning japanese and wanting to become a translator in the future! It’s so cool to see different types of characters using different pronouns that “match” their personalities. It’s fun to try and kind of a non-Japanese tv series/books/etc and try to guess which personal pronouns the characters would use in a translation.

My favourite translation of ore-sama has to be “Ya boy!” in Pokémon Sun and Moon with Guzma.

Also, Chouchou from Boruto uses “Ashi” to refer to herself, which I assume is kind of a lazy way to say Atashi (it does fit her easy-going attitude overall).

Also! Forgot to add, but Lal Mirch from Katekyo Hitman Reborn! also refers to herself as “ore”. Considering she’s a tough-as-nails soldier lady, it’s no wonder.

Man, the two Sekiro mentions are making me curious as to what pronoun(s) Sekiro himself uses. Unfortunately, throughout the game he has a lot of lines that are basically just denials and affirmations, so it’s hard to find out when he might say it/them. Probably when conversing with Kuro at some point… With a lot of other characters, you get a nice “I am x” bit of dialogue; found a fair few “washi”s that way. Apparently the original script isn’t written with an emphasis on historical accuracy so there are some modern pronouns (or those used much more often now than hundreds of years ago) alongside your “sessha”s and “soregashi”.

This article made me think of the Hanar from the Mass Effect series, and now I’m wondering what they say.

I checked, and they seem to use “kono mono” (this thing/object) and “kore” (this) for themselves.

Starting up the original Starfy game in Japanese and was really thrown by the old lobster man’s use of ワシ until I remembered this article! And sure enough, there’s Washi in the article. Helped me get my bearings a lot in the story because I thought we were talking about an eagle (わし) at first. I enjoyed reading this article a lot so I’m glad it stuck with me.

The partner character in Mystery Dungeon Explorers talks in a slightly different manner depending their species and/or sex (this is also reflected in English, which is why the text dump floating around repeats player and partner lines up to three times [usually worded slightly differently each time]). I’m not certain on this, but I think females generally use わたし [and more hiragana in general; iirc Pokémon games didn’t use kanji until Gen. 5], whereas males use either ボク or オイラ.

I’m curious about the usage of the pronoun “atashi”. Is it okay to use in real-life informal contexts, then? (I just wonder why it’s under the “secondary” section; I assume it’s because it’s seldom seen in written form as opposed to spoken.)

Another question about it, I also got the impression that “atashi” is used by sort of rough or tomboyish female characters as well, is that impression wrong?

I’d also like to mention another usage for this pronoun that you missed. Effeminate male characters, who may or may not be gay or cross-dress, use “atashi” a lot, too.

> Is it okay to use in real-life informal contexts, then?

Totally okay. It is used by many women of all ages and personalities in casual conversation.

> I also got the impression that “atashi” is used by sort of rough or tomboyish female characters as well

Correct, but it’s also commonly used by other types of women.

I’ve been playing a lot of Hyrule Warriors: Age of Calamity with the JPN dub voices, and interestingly, Revali actually uses ‘boku’ in at least one cutscene (the pre-Divine Beast portion of “Freeing Korok Forest”, to be exact. Unfortunately, I can’t really catch many other pronouns used. I remember that one specifically because I had a bit of a (very) minor freakout about it.

And I’m also curious about some other characters’ pronoun usage in JPN dubs of games. Namely from ES5, the DLC characters Harkon and Miraak; and from AoC, Astor, the fortune teller main bad guy. I can kind of picture the former using the more archaic ones due to their ages, but I’m at a loss for the latter.

One thing I have to wonder is if you have an article on the many ways to say “you” but that would probably be hell to make lol

Miss Impact, the female counterpart to Goemon Impact uses “Atai” or at least her theme song does. The song can only be heard on the japanese version of “Goemon’s Great Adventure”.

Doraemon uses “boku”, as per its catchphrase “Boku Doraemon”, which could be translated as “I’m Doraemon”.

In addition, the game “WarioWare D.I.Y (Do It Yourself)” is known in Japan as “Made in Ore”, which could be translated as “Made in Me”.

This is too NSFW, but the hentai anime “Boku no Pico” uses “boku” in the title. Therefore it could be translated as “My Pico”.

http://naisen01.livedoor.blog/archives/cat_328995.html

Here, we got first-person pronouns for Hebereke characters. Only three of them are defined.

Hebe uses “wachi” (not listed), Oh-Chan uses “watakushi”, and Sukezaemon uses “sessha”.

Another character that uses oira: Willie Trombone from the Japanese localization of the point-and-click game The Neverhood. Here’s an excerpt of him telling the story of the creation of the game’s world in the original English so you can see why they might have chosen “oira”:

“Erm…

Hello!

Me Willie.

Me Willie Trombone!

These disks tell a story. Story about good. Story about bad.

These disks are all that are left of the TRUE story…

True story of the closing of the third age.

Willie know that once you know this truth, then you know what to do.

Listen. I tell you.

It all start with Hoborg, him being who had to create, because… He had to. He make him world full of beauty, and wonder. This world, the Neverhood, a world where he could live forever and EVER more.”

Feel like Atashi should be moved up with Watashi/Boku/Ore in the “Everyday Pronouns” section, since it’s really prevalent.