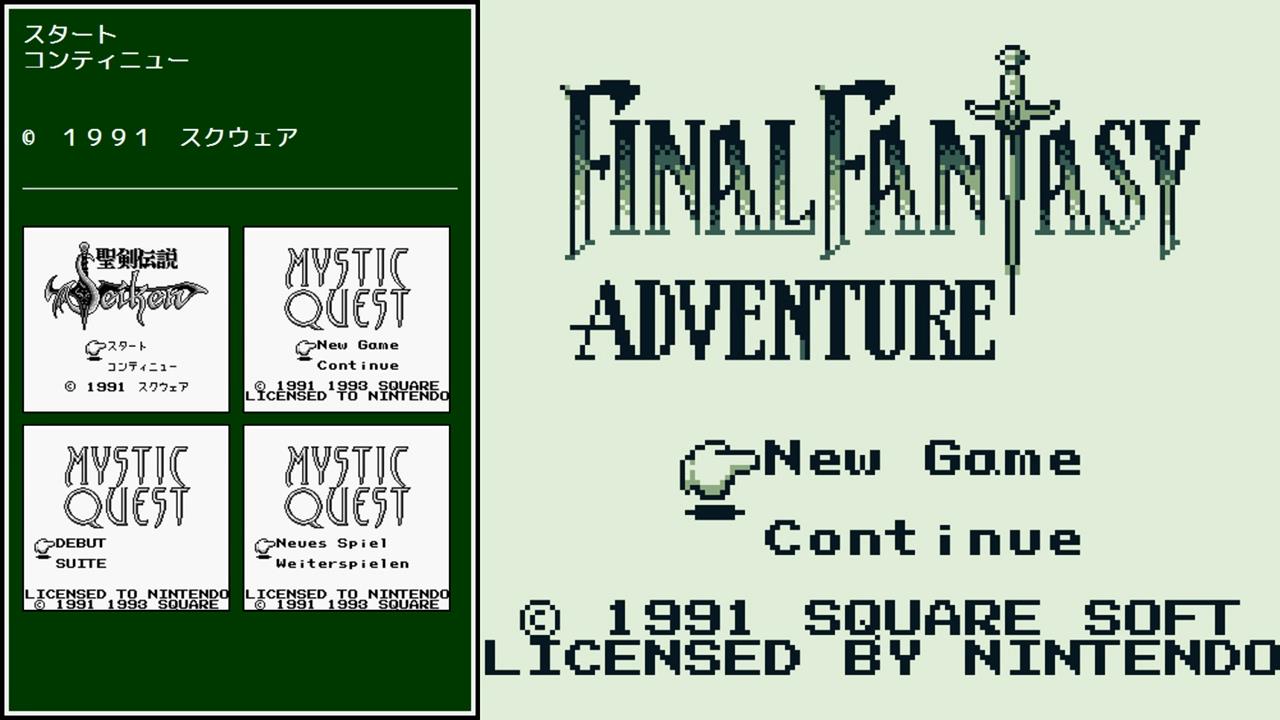

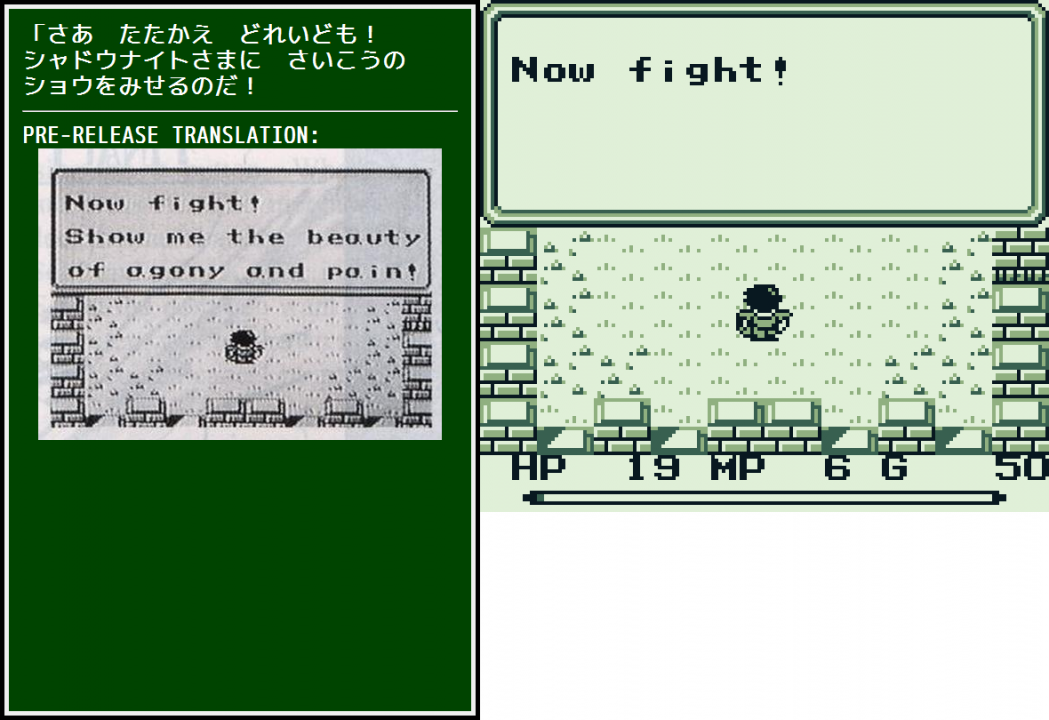

In July 2019, I streamed Final Fantasy Adventure (Game Boy) on Twitch. Specifically, I compared its English translation with the game’s original Japanese script. The whole playthrough took about fifteen hours and was spread across seven different days.

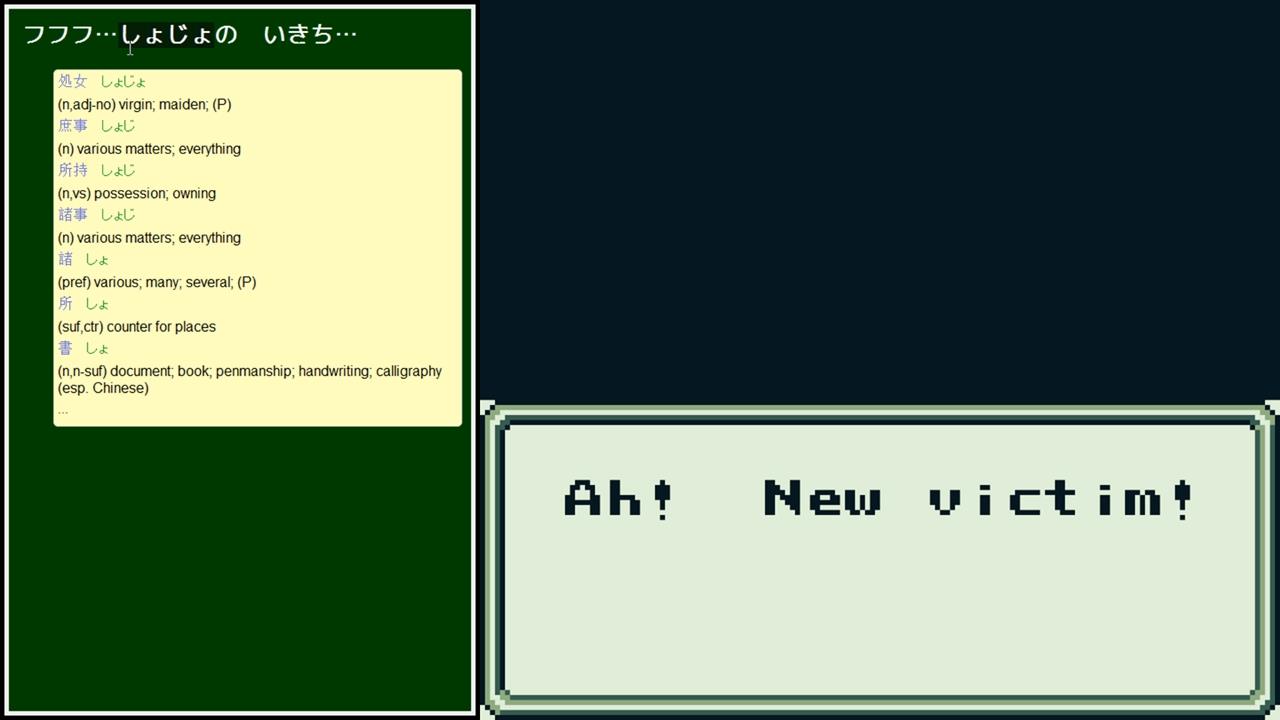

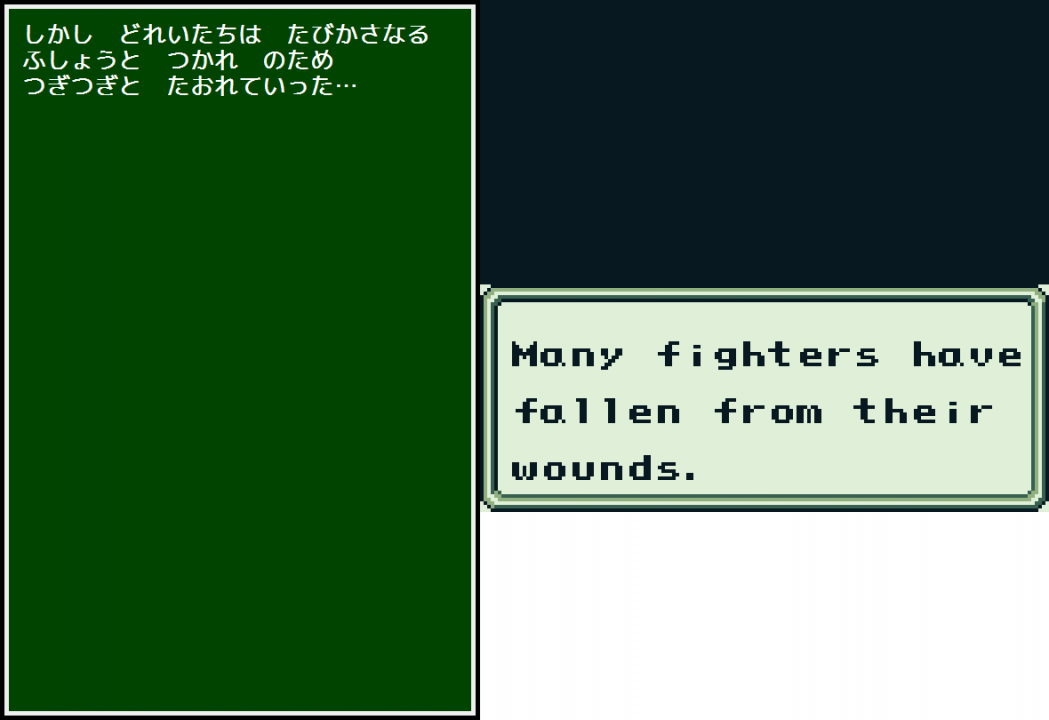

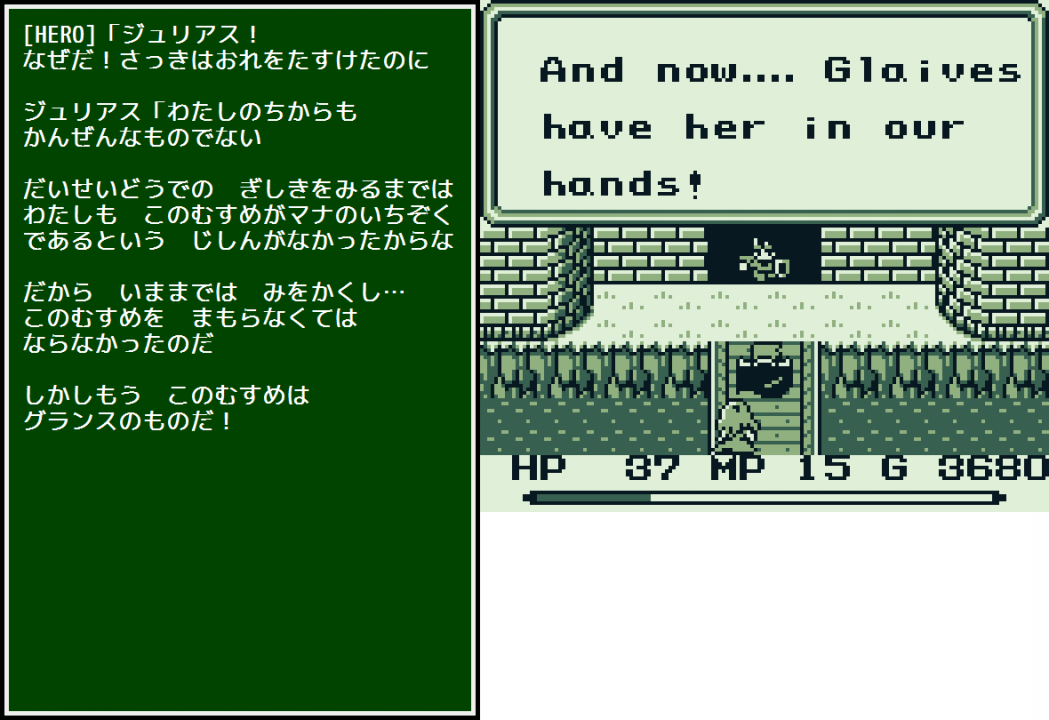

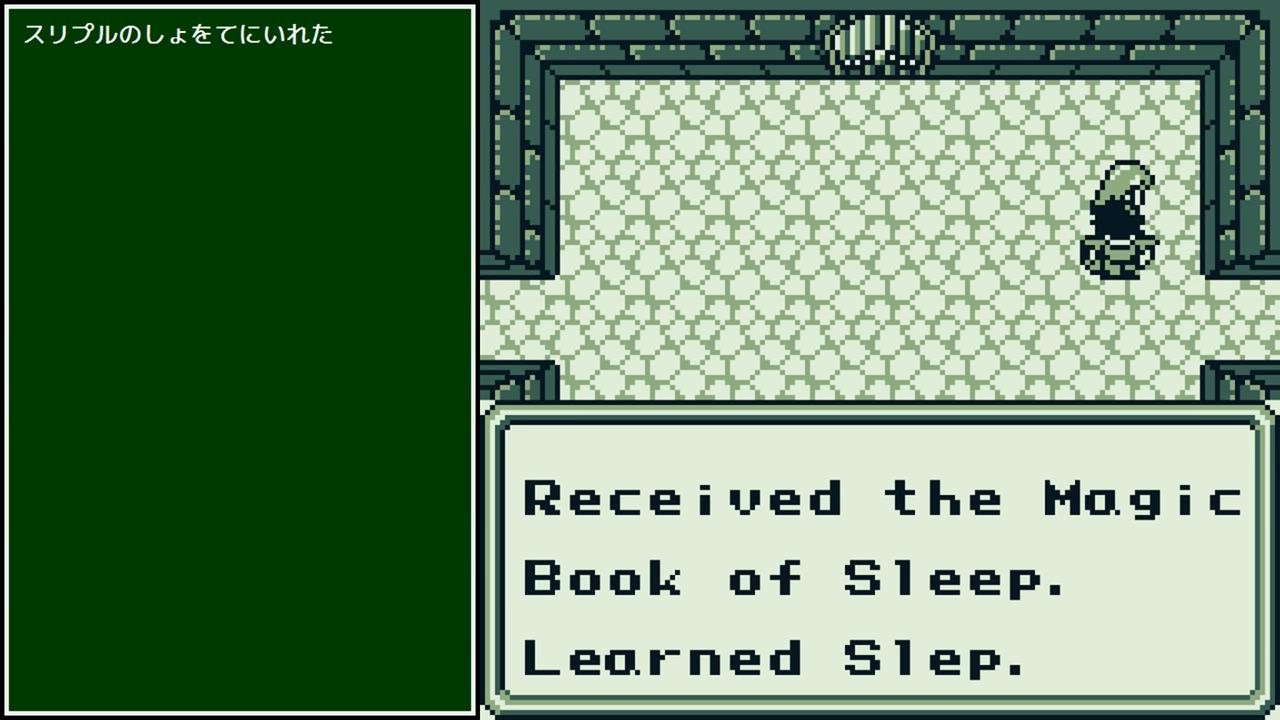

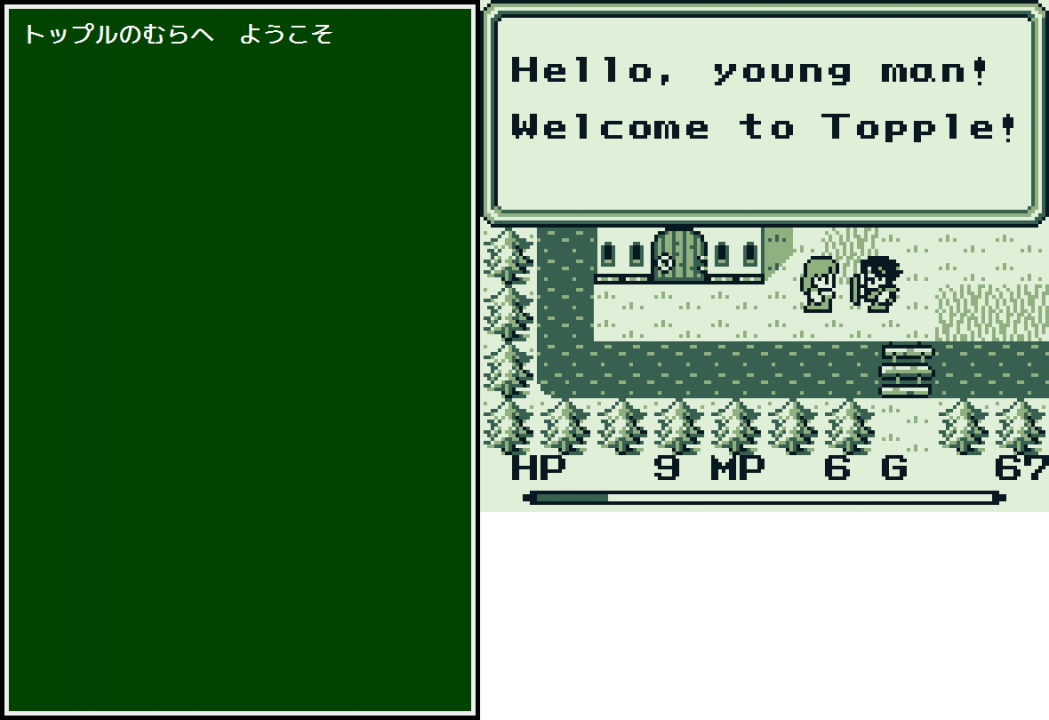

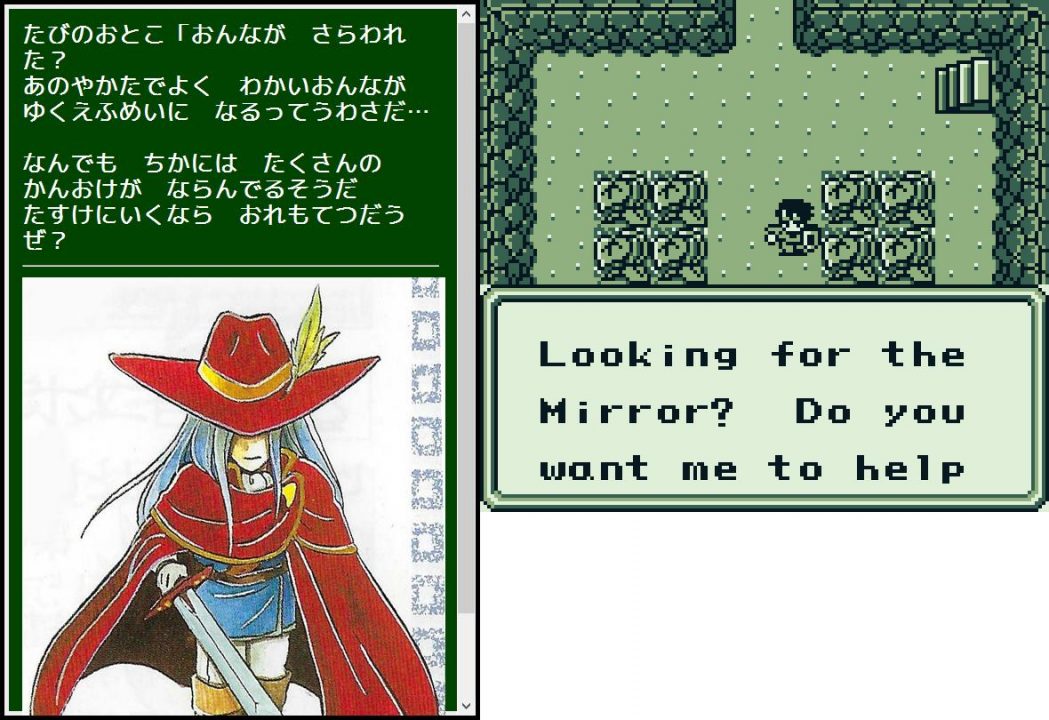

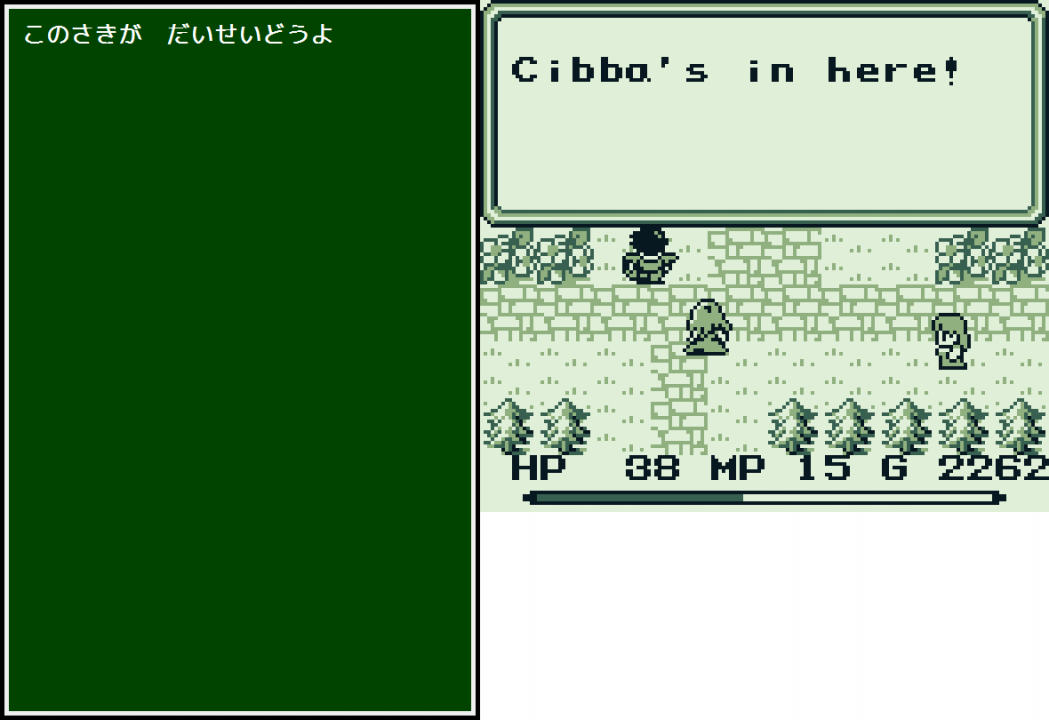

Just like my previous live comparison translations, I used a custom Wanderbar plugin to make the comparison easier and more interactive:

Part 1: Game Start to Airship

I hadn’t really played Final Fantasy Adventure in about 25 years, so I wasn’t sure how far I’d get after this first stream. I wound up getting about twice as far as I had anticipated. You can watch this day’s archived stream here:

In the notes below, we’ll look at some key things I noticed during this day’s playthrough, but I actually cover many more translation changes during the stream. So if you find this stuff interesting and want to dive even deeper, definitely check out the video!

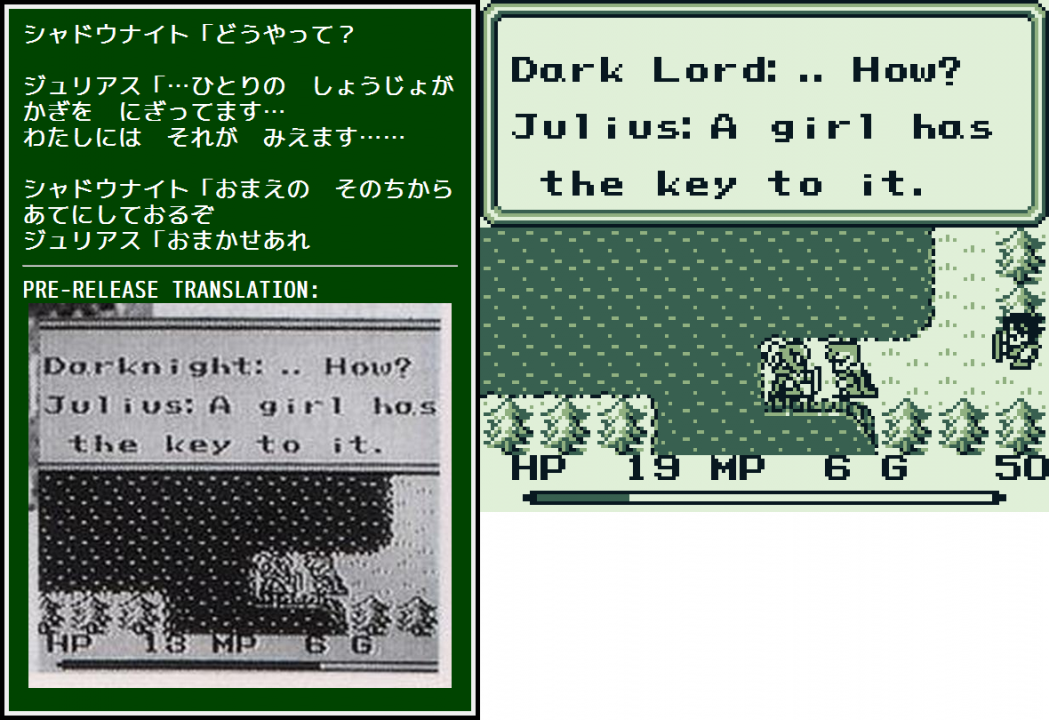

Pre-Release Peeks

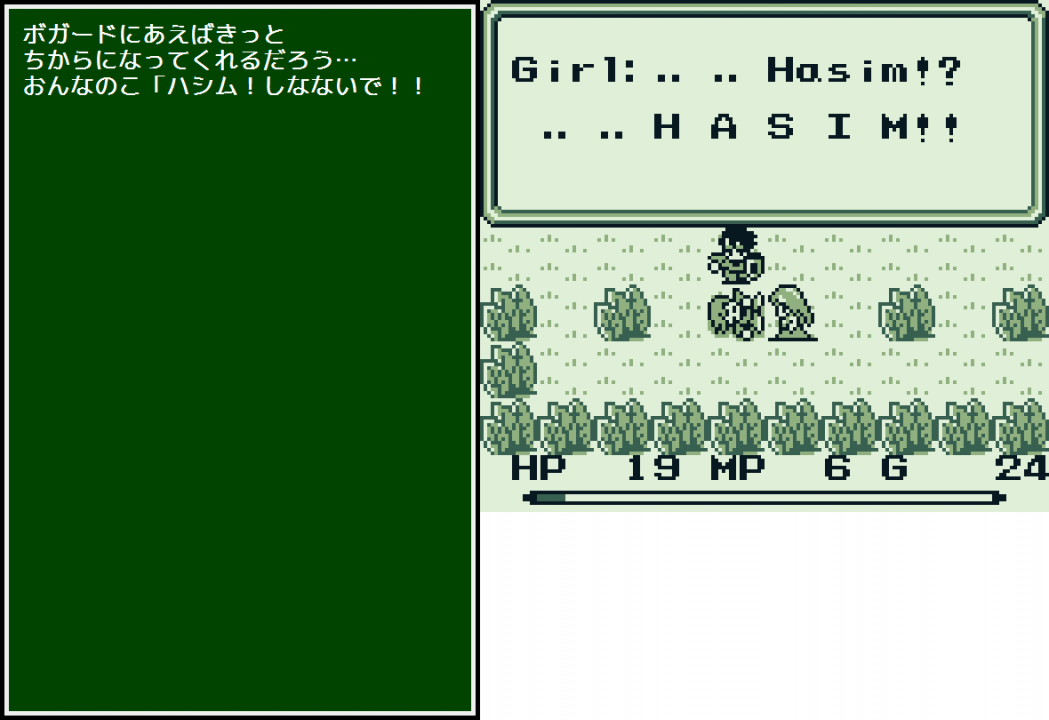

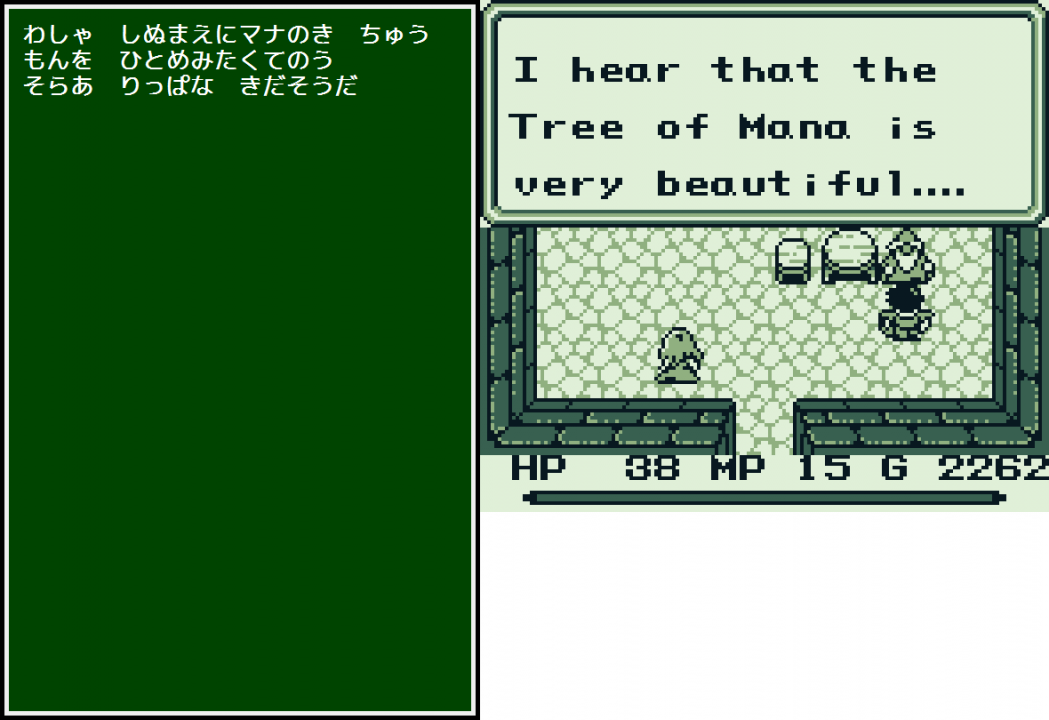

At a couple points during the stream series, I shared some translation screenshots from before Final Fantasy Adventure was released.

I find stuff like this fascinating, so if you know of any other pre-release translation screenshots from the game, let me know!

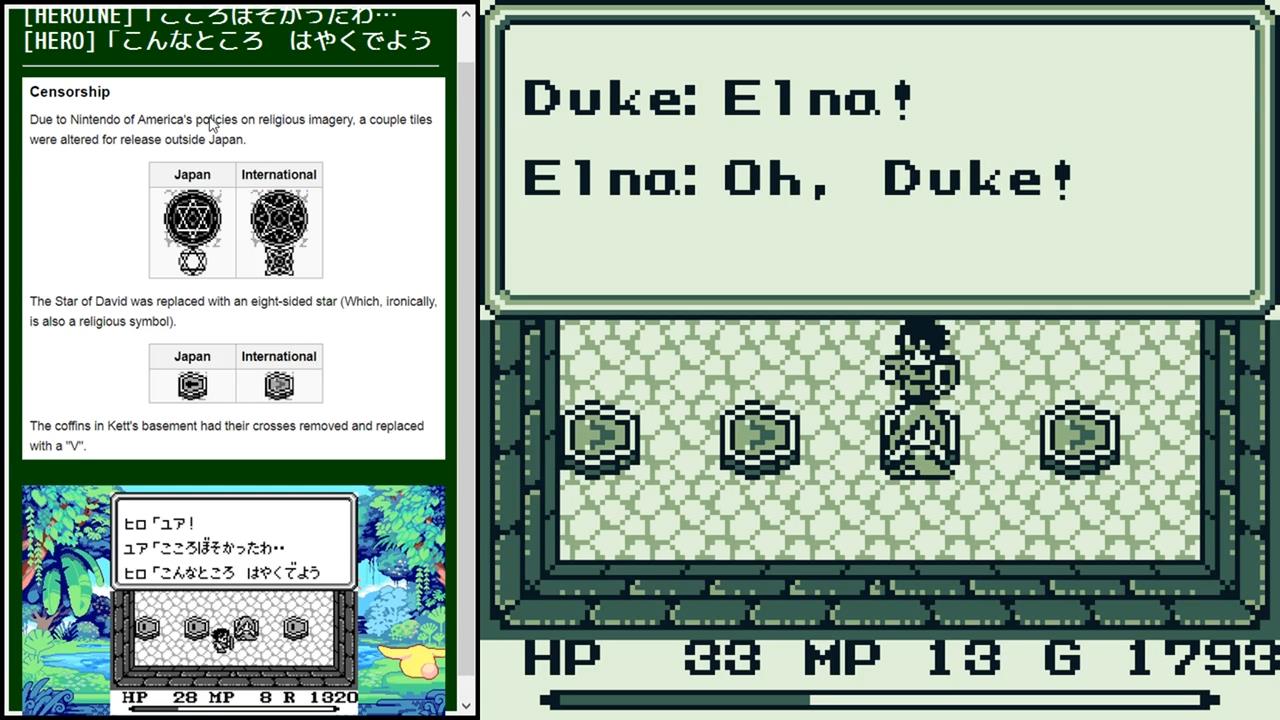

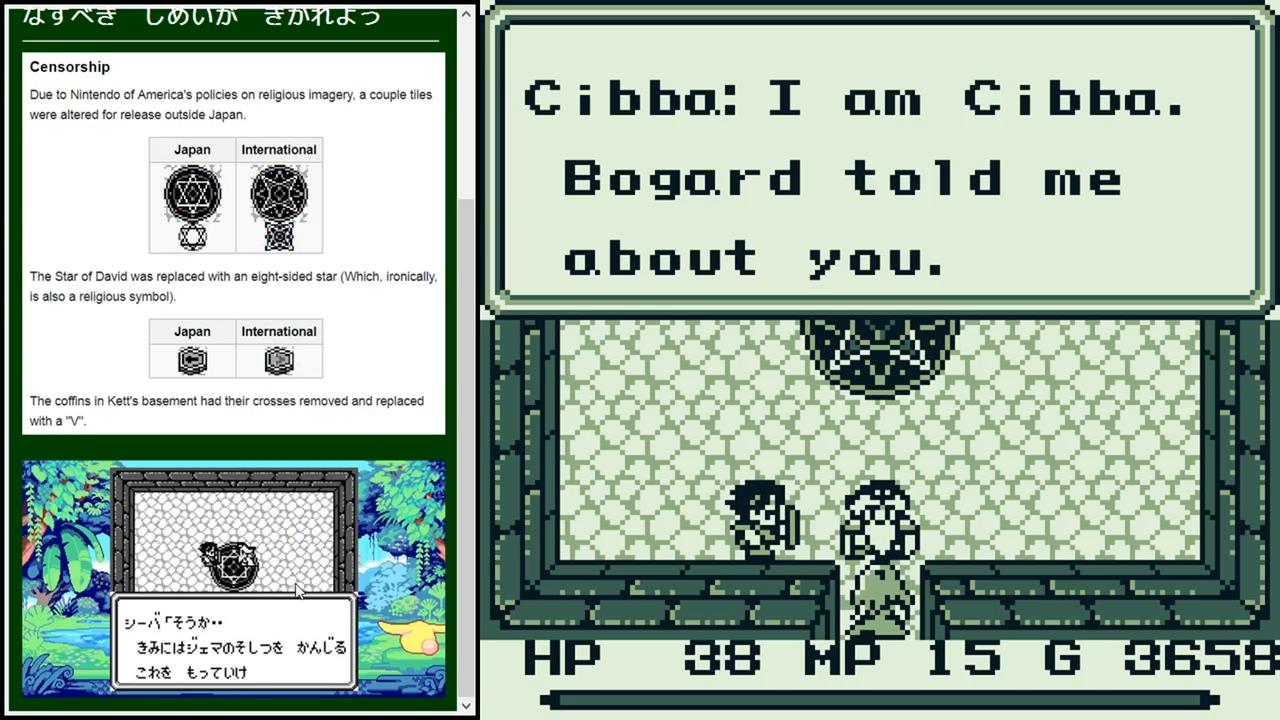

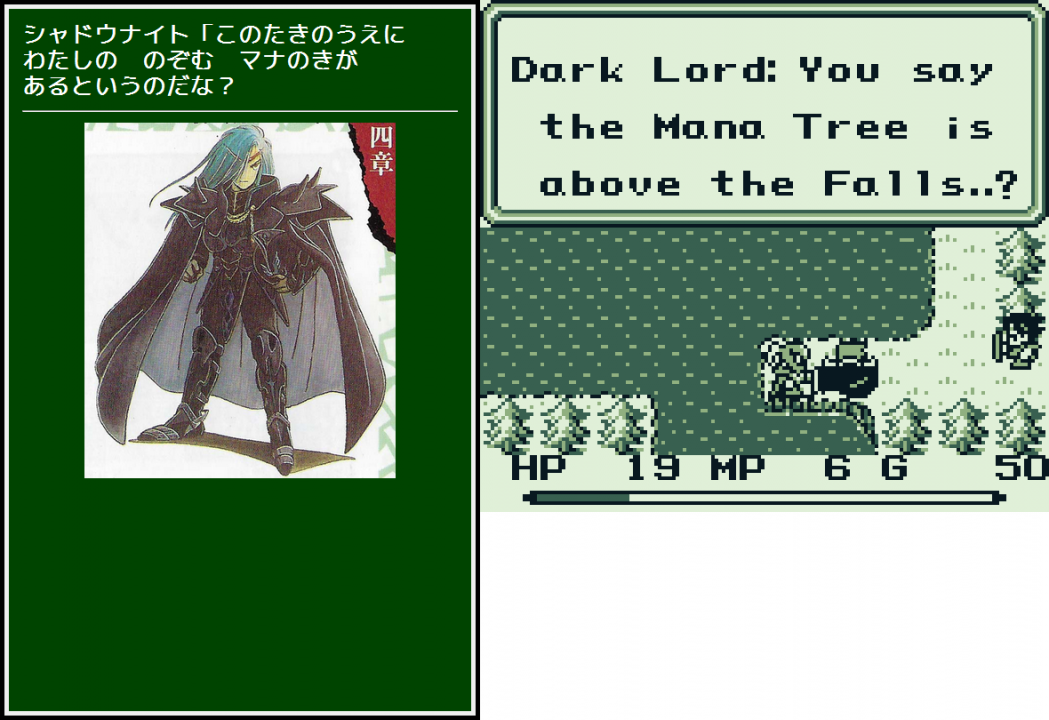

Content Policy Changes

During this stream, we encountered a number of things that were changed to adhere to Nintendo of America’s content policies at the time.

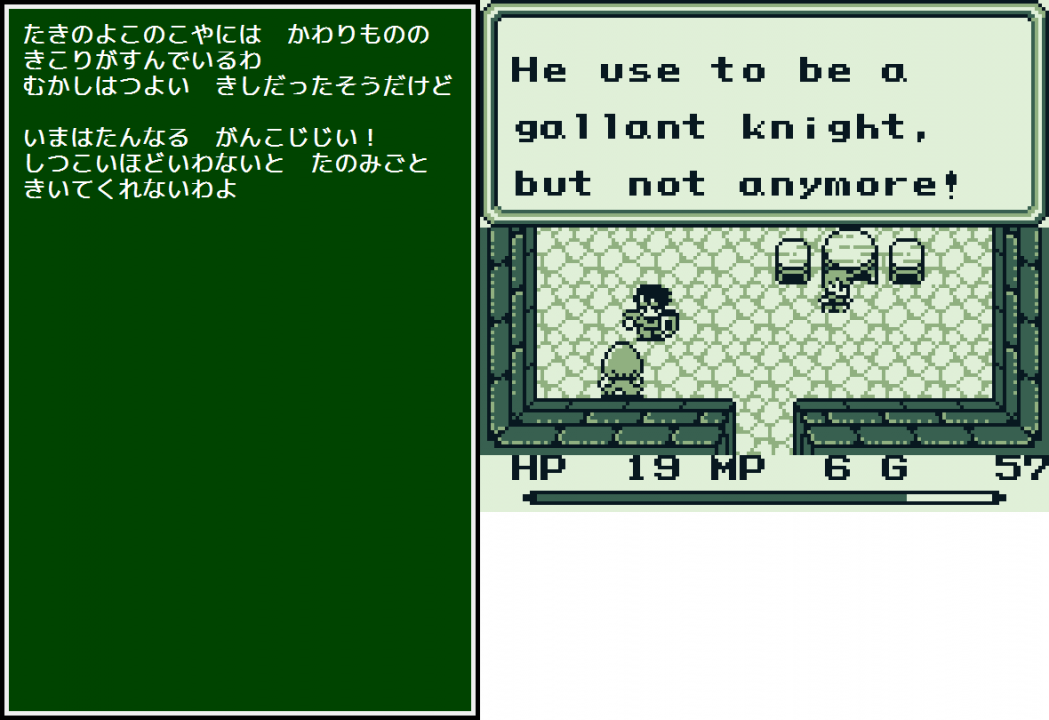

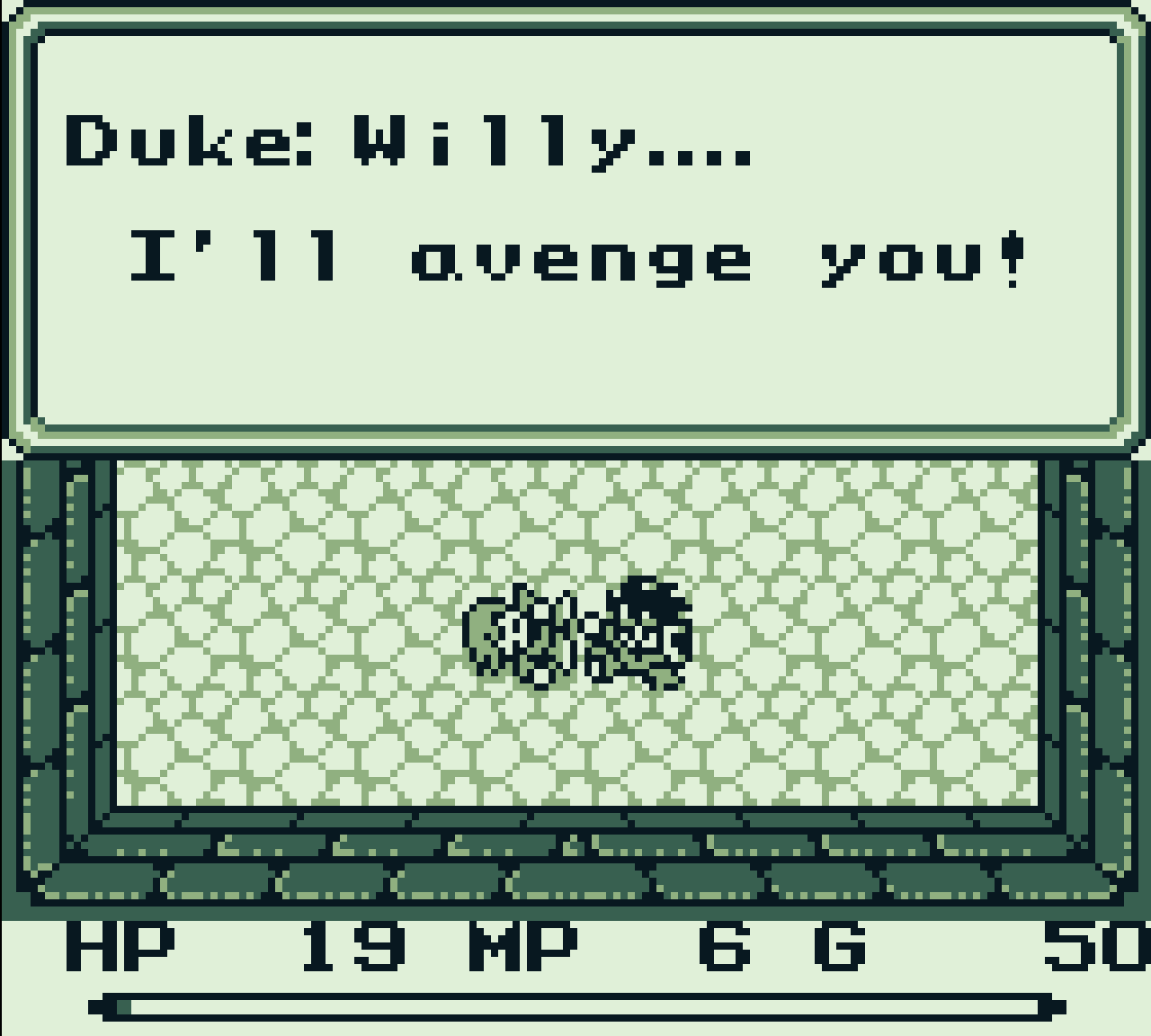

Text Quality

It probably goes without saying, but the English text in this game is full of issues. Grammar and spelling mistakes abound, and awkward, unnatural wording is everywhere.

These kinds of text problems persist throughout the game. In fact, they actually get worse as the game progresses – I’m guessing it’s because the earliest content received the most post-translation attention.

Inconsistent Changes

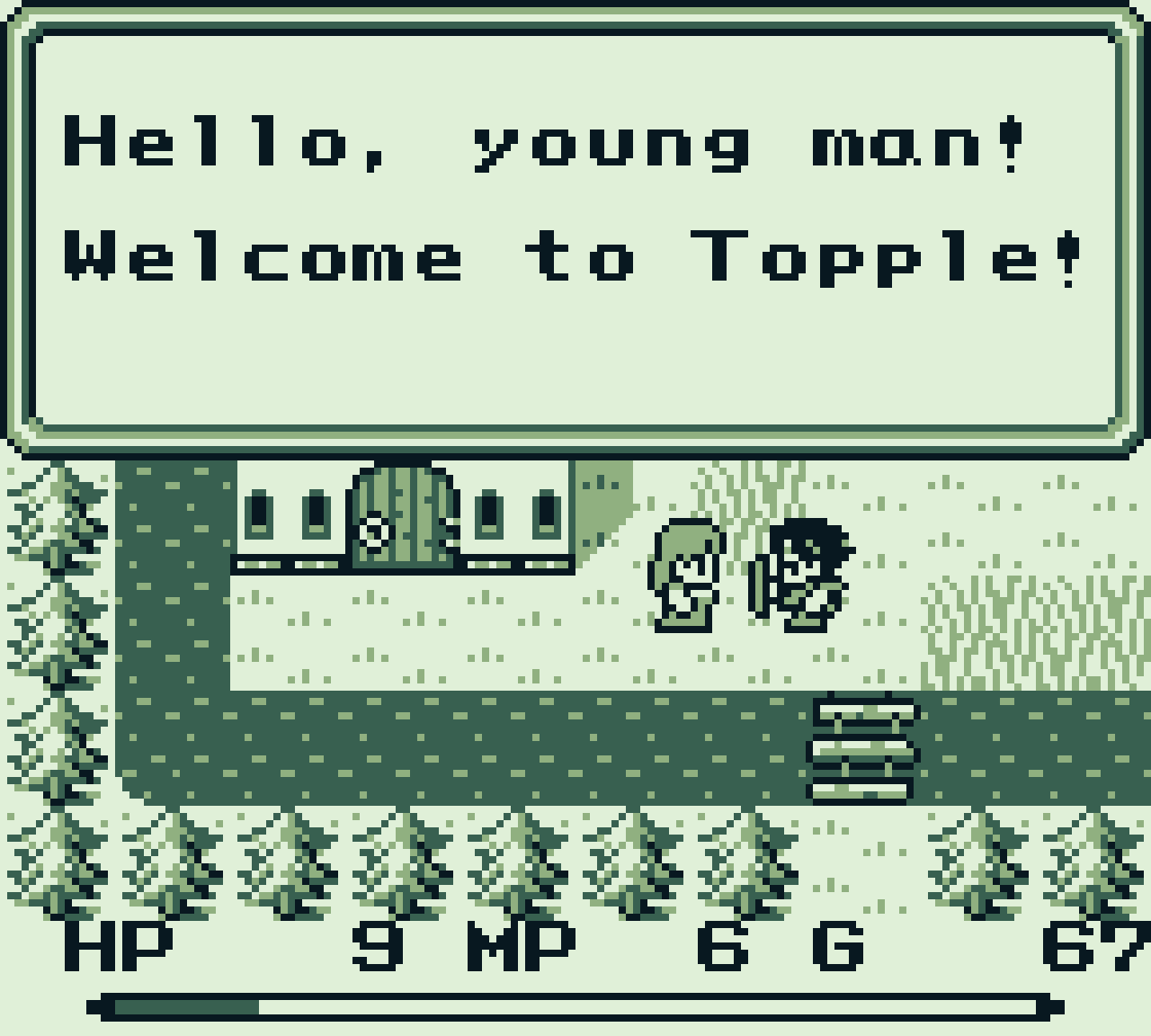

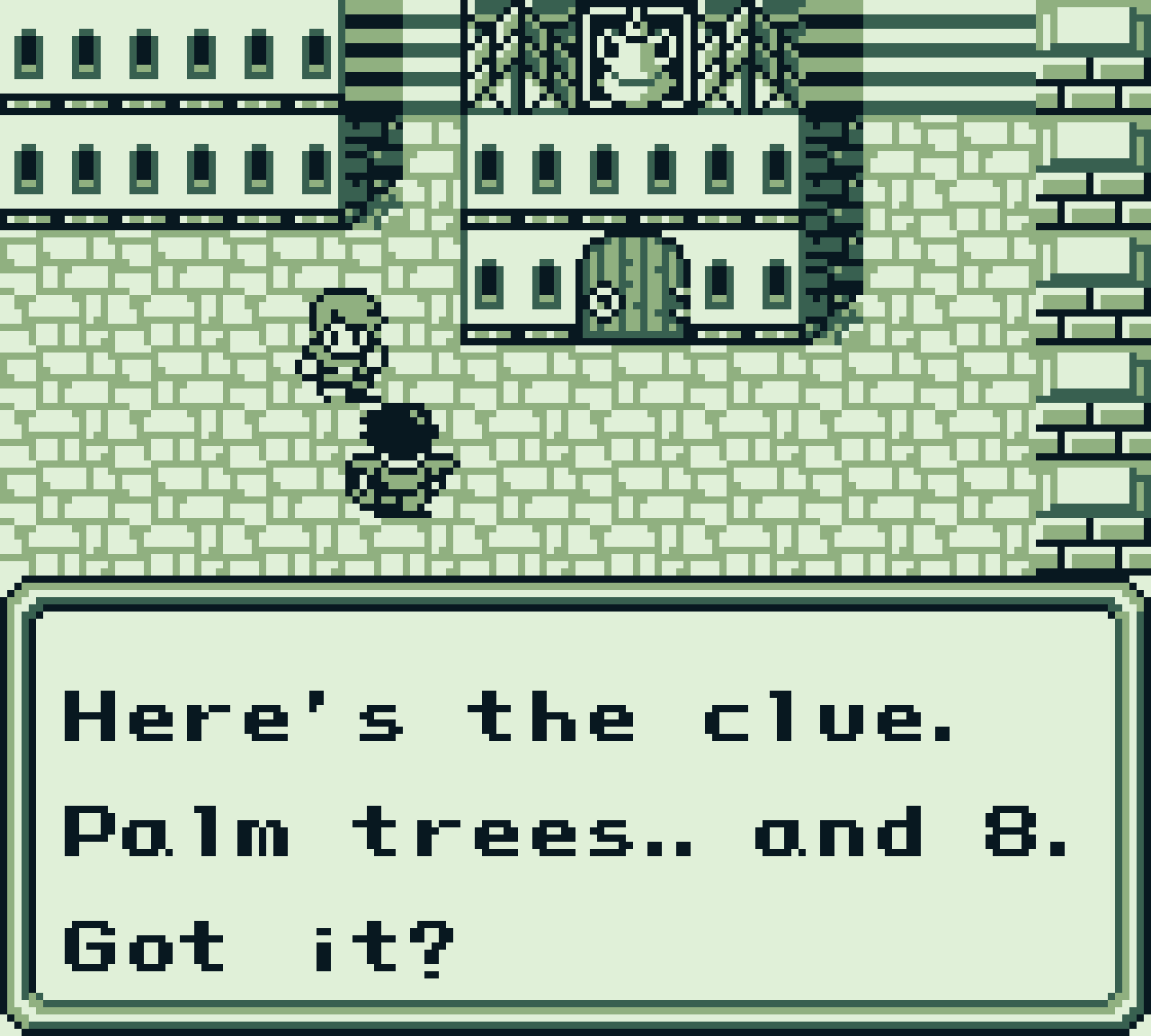

A lot of text was trimmed down or dropped entirely during the translation process. Even gameplay hints and details were affected, right from the start of the game.

Basically, beyond the issues mentioned above, the game’s English script is filled with little, inconsistent changes everywhere.

Name Changes

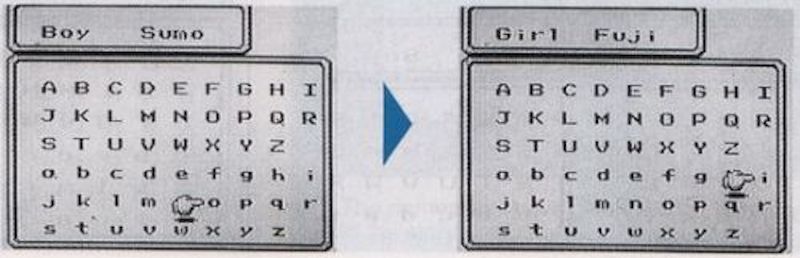

Screen space and cartridge space was very limited on the original Game Boy, so many things throughout the game were renamed during localization to accommodate these limitations. Other names were changed for other, unclear reasons.

Naming the Characters

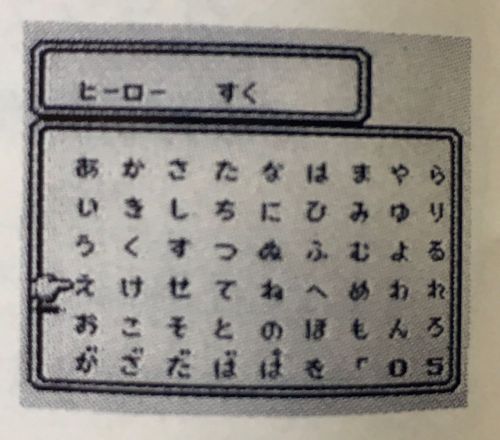

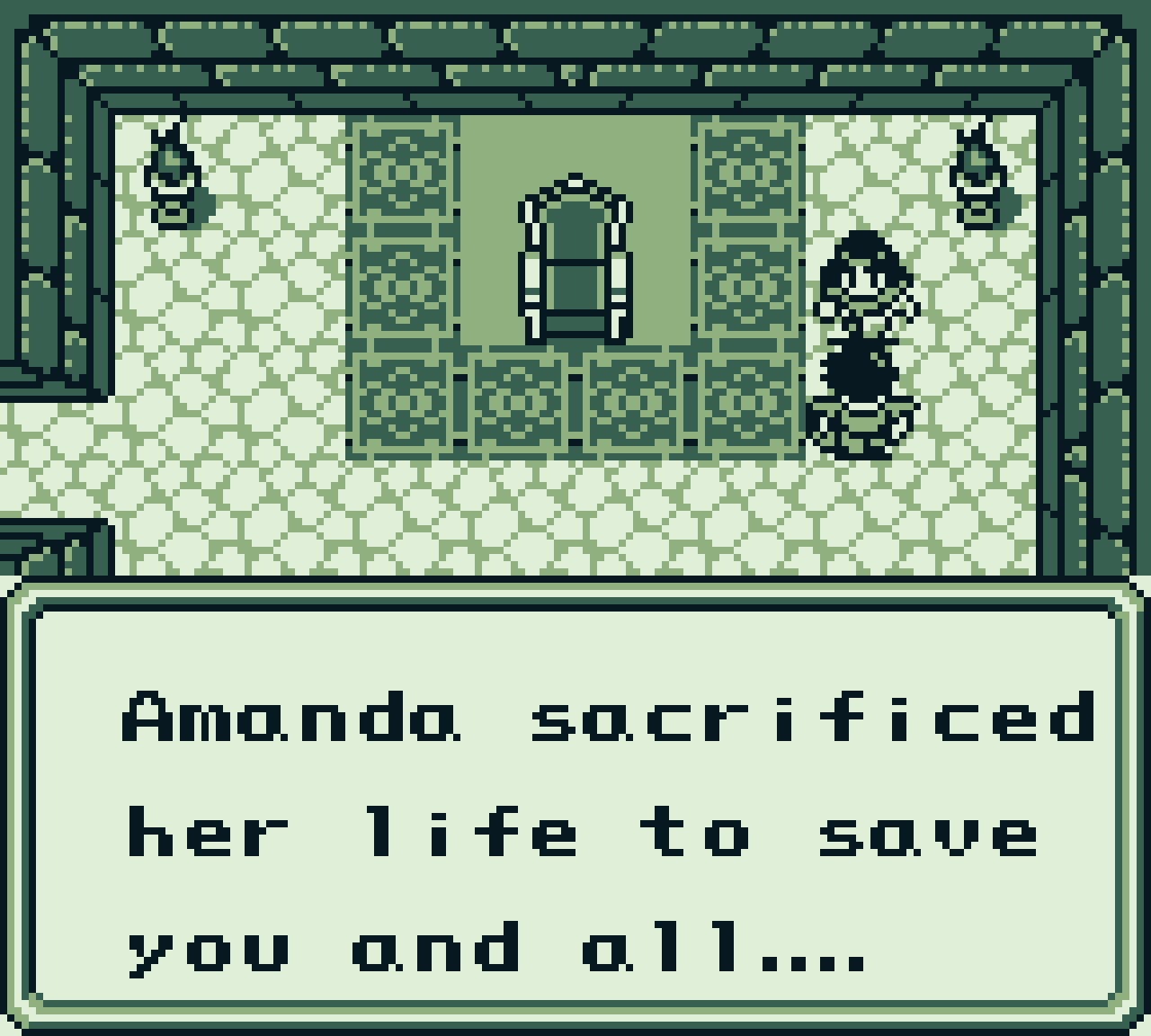

At the very start of the game, you’re asked to name two characters: the hero and the heroine of the story. There are no default names, however. This isn’t really a problem for the player, but it becomes a problem when fans want to discuss the game.

Japanese Names

If you were playing Seiken Densetsu when it was first released, how would you determine what the heroes’ official names were? You’d probably turn to the game’s manual and/or the game’s strategy guides.

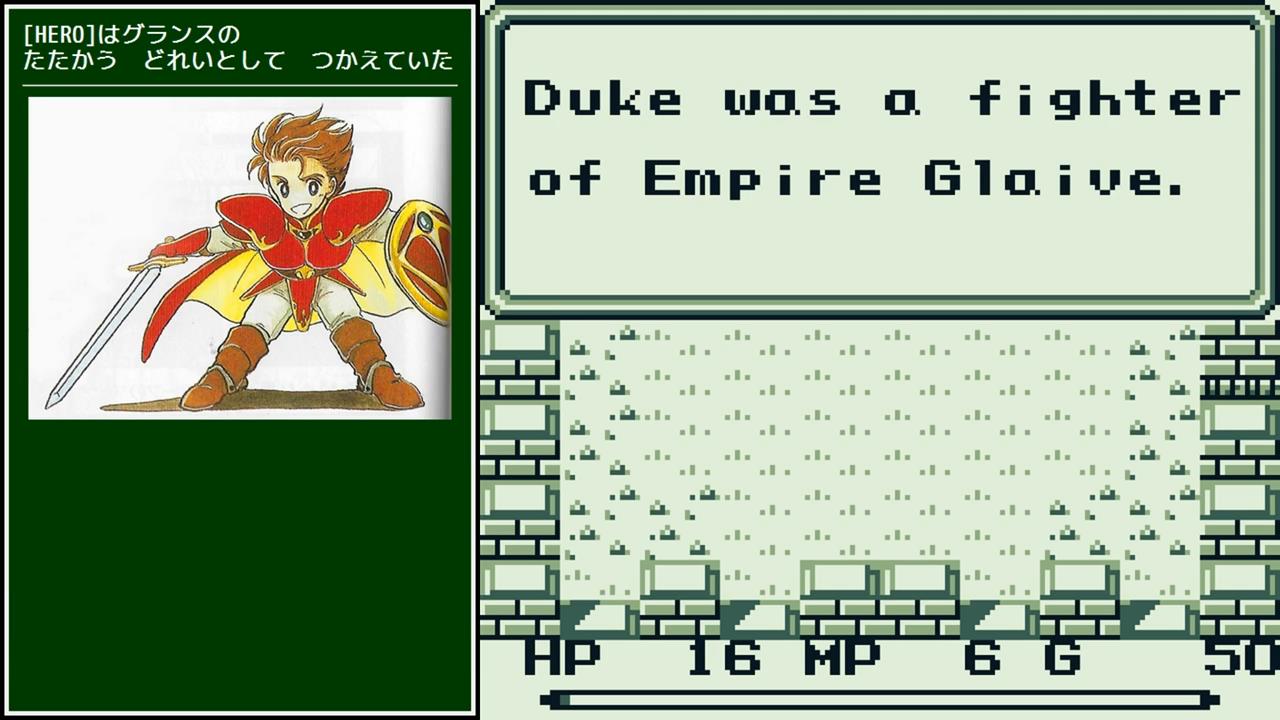

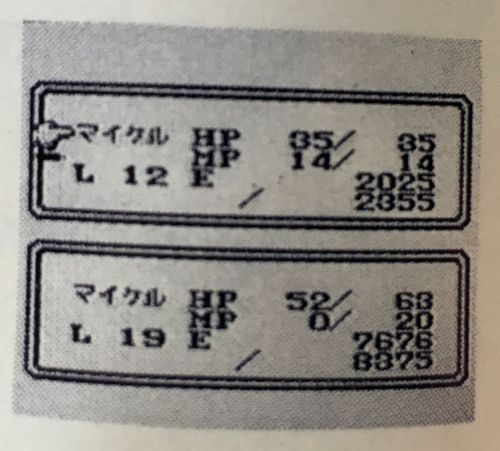

Unfortunately, official names aren’t given in the manual’s text. Still, some tiny screenshots do feature the placeholder name すくえあ (sukuea, "Square") for the guy and すくえり (sukueri, "Squari") for the girl. The name “Michael” appears as well:

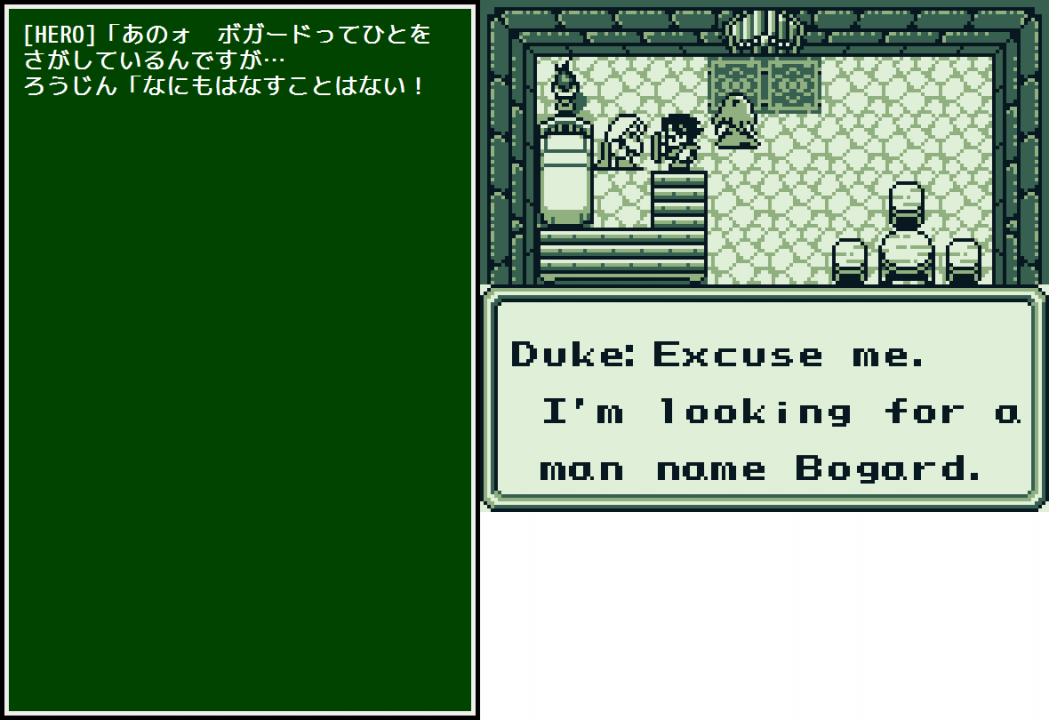

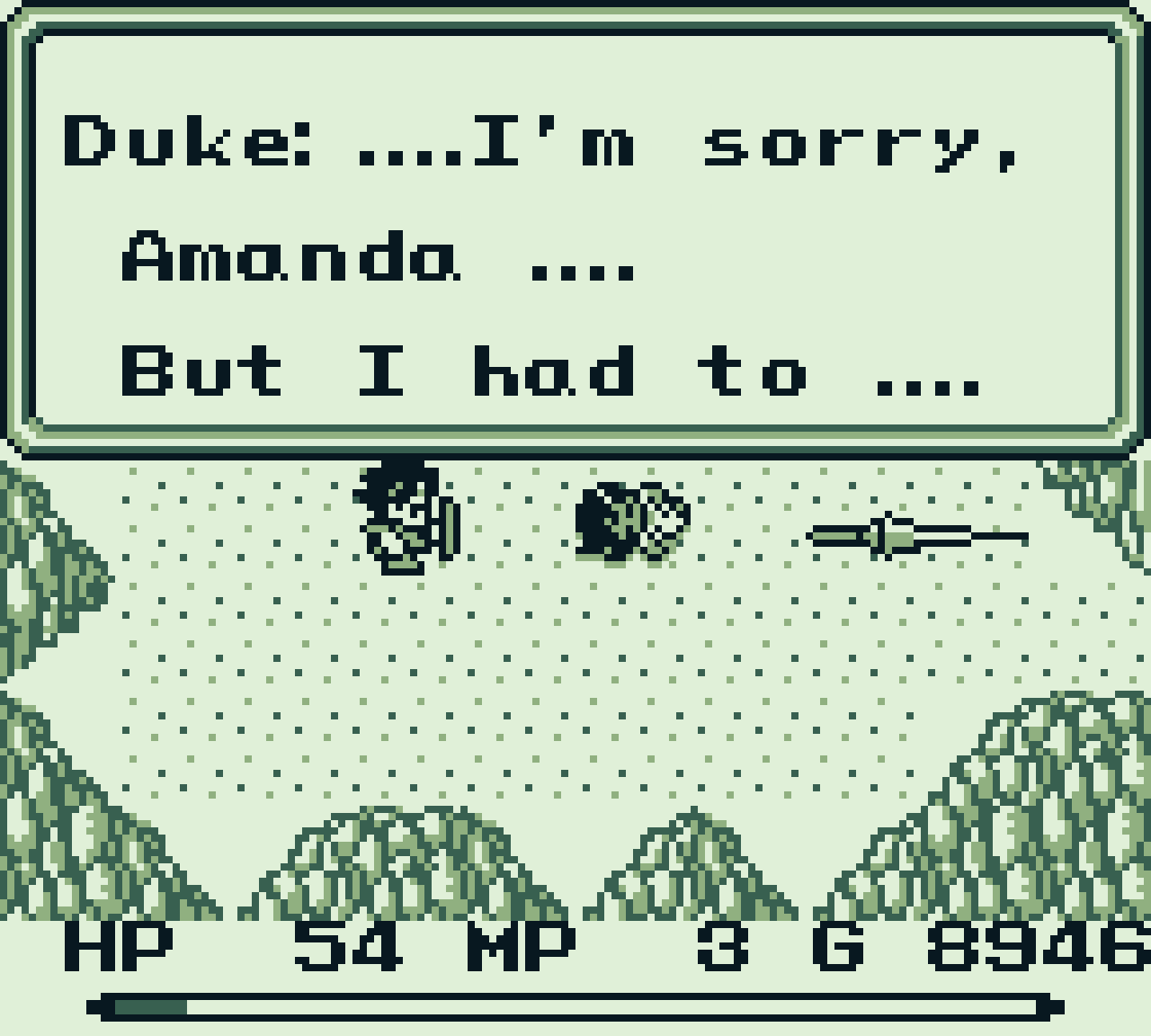

Apparently the names “Duke” and “Elena” became semi-official when the Game Boy Advance remake was released in Japan, but I haven’t looked heavily into it myself. I’ve also read that the game’s Japanese novelization used “Duke” and “Elena”, but I haven’t obtained a copy to confirm it yet.

Despite these potentially new, official names, the characters’ names remained unclear in the Vita remake of the game released a decade later:

English Names

If you were playing Final Fantasy Adventure when it was first released, how would you determine the heroes’ official names? The English manual, which is quite different from the Japanese manual, was the only official supplemental material available.

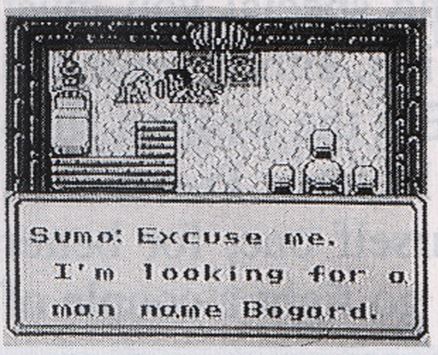

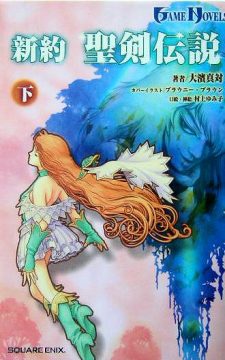

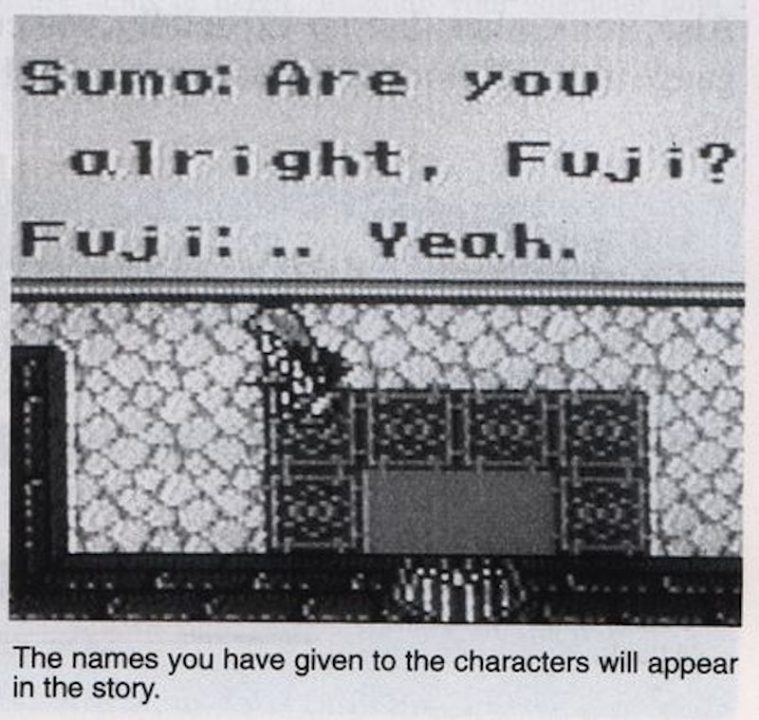

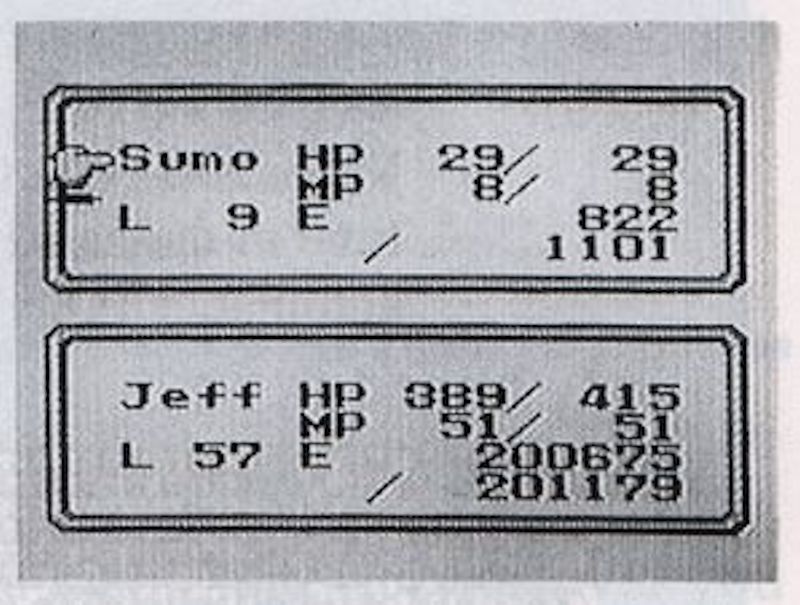

Similar to the Japanese manual, official names don’t appear in the main text of the English manual. There are only some tiny screenshots with the names “Sumo” and “Fuji” visible:

My assumption is that someone in the company – maybe this mysterious Jeff – was assigned to take screenshots for the English manual and was just like “I dunno what to call these guys from this Japanese game, what’s something Japanese I can call ’em?” and went with “Sumo” and “Fuji”.

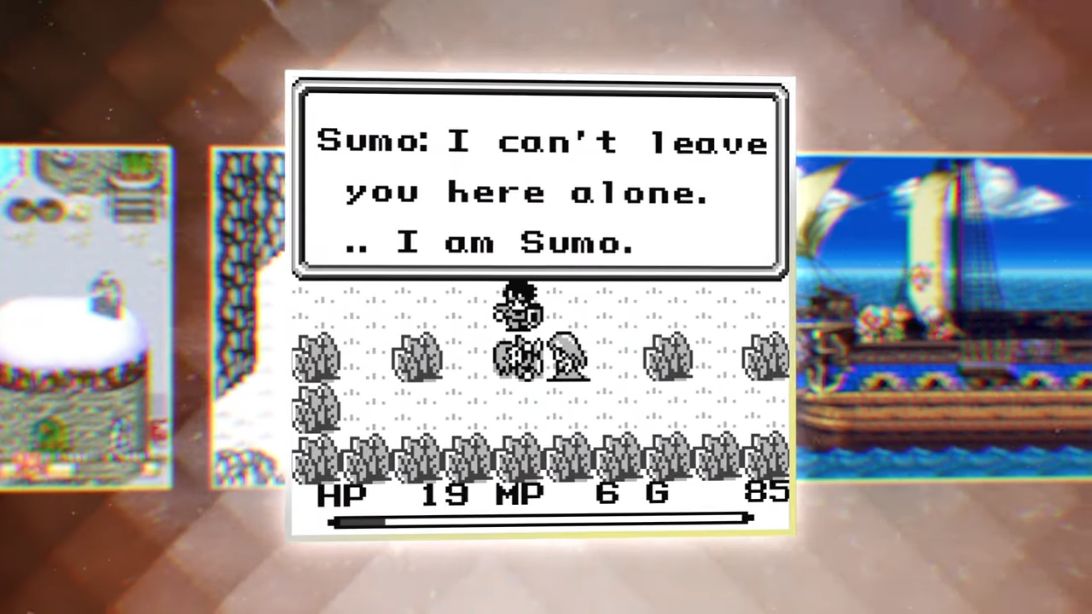

Whatever the case, English-speaking fans have called them Sumo and Fuji ever since. The Sumo name even got a shout-out in the trailer for the Collection of Mana release:

This “let’s name this unnamed character based on game manual screenshots” reminds me a lot of how the main character of the first MOTHER game wound up with the name Ninten.

Anyway, all of this is a long-winded way of saying that the “Sumo” and “Fuji” names are an entirely outside-of-Japan thing. They have their own sorta-but-not-really official names in Japan, but they’re completely different for different reasons.

Leveling Up

I noticed a couple interesting translation changes during the whole level-up sequence.

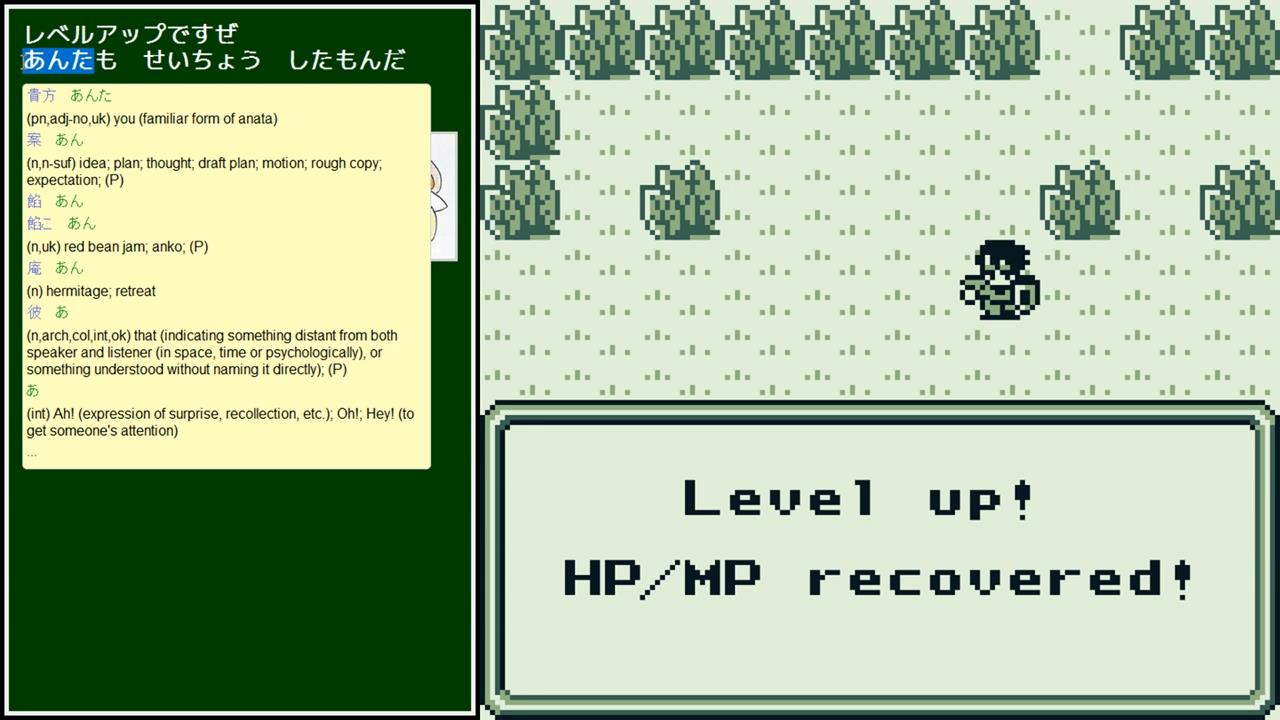

First, the Japanese “you leveled up!” message is very colloquial and is phrased like someone is actually saying it to you. In contrast, the English message is a generic user interface message:

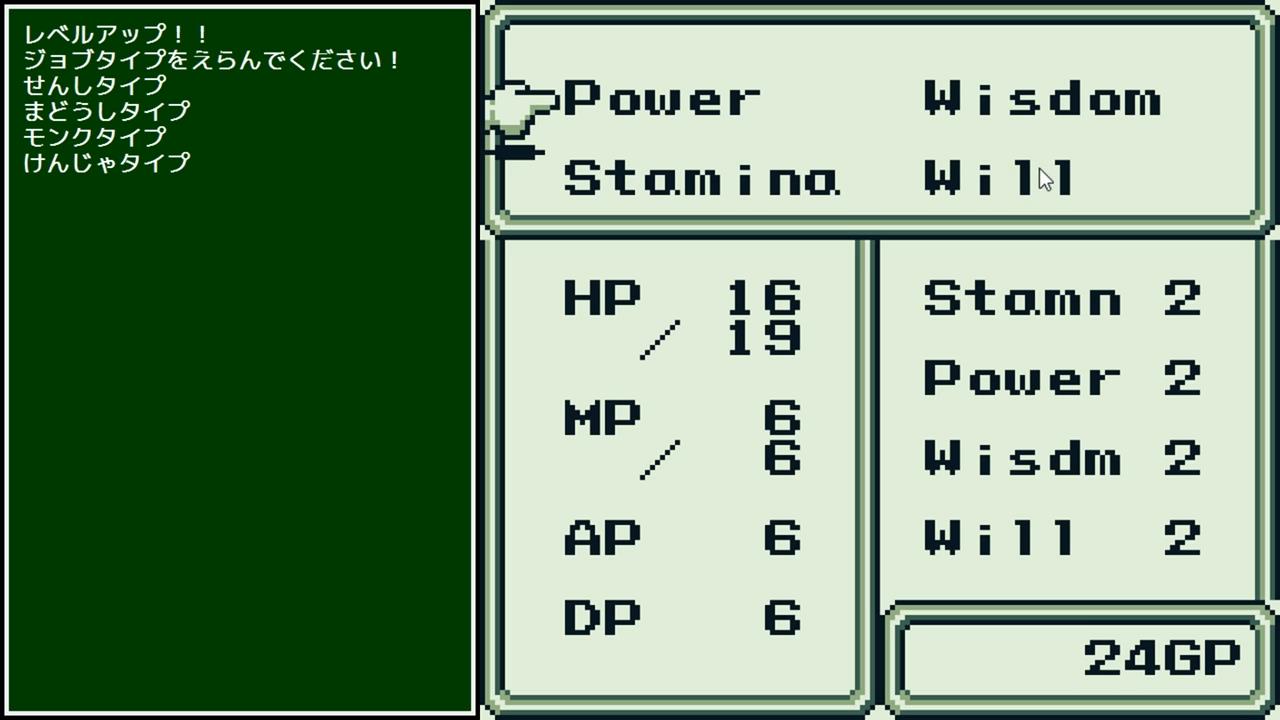

Next, whenever you level up, all your stats get a boost, but you get to choose a stat that gets an even bigger boost:

In Japanese, you’re asked to “choose a job type”, and you get to choose one of these four:

- Warrior type – extra boost to Strength

- Wizard type – extra boost to Wisdom

- Monk type – extra boost to Stamina

- Sage type – extra boost to Mind

Note that these Final Fantasy-style job types, so “monk” for instance refers to the type of Yang-like martial arts monks seen in those games. Final Fantasy was a huge phenomenon in Japan by this point, and multiple games in the series had already been released.

In the English version of this game, however, there’s no mention of job types anymore. The text was rephrased so that you simply choose a stat name instead. I assume this simplification was done in part because Final Fantasy was still very new at the time for audiences outside of Japan – only the NES game had been released prior to Final Fantasy Adventure. Final Fantasy II for the Super NES hadn’t been released yet.

Anyway, this job type stuff did survive the localization process in later remakes of the game, as we can see here:

Horror Homage

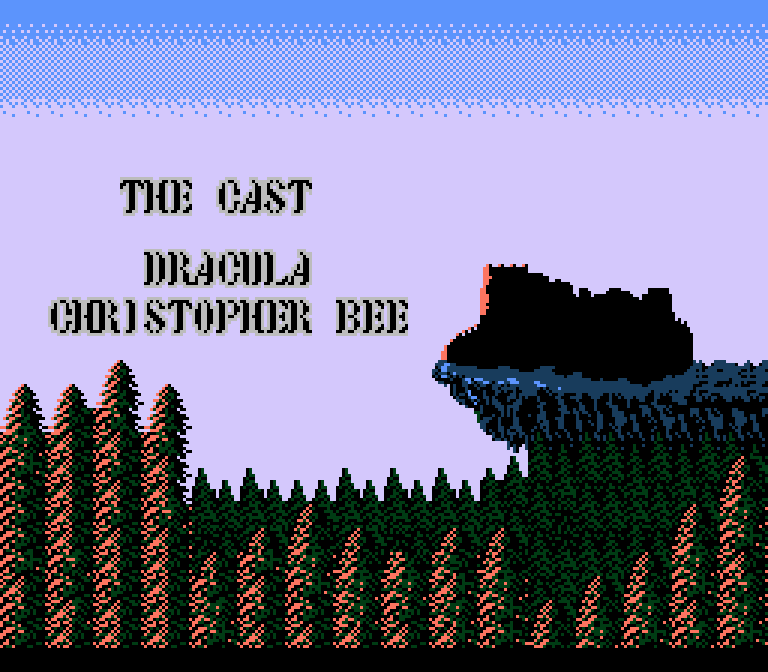

Early in the game you visit a spooky mansion with werewolves, monsters, and even a big vampire boss.

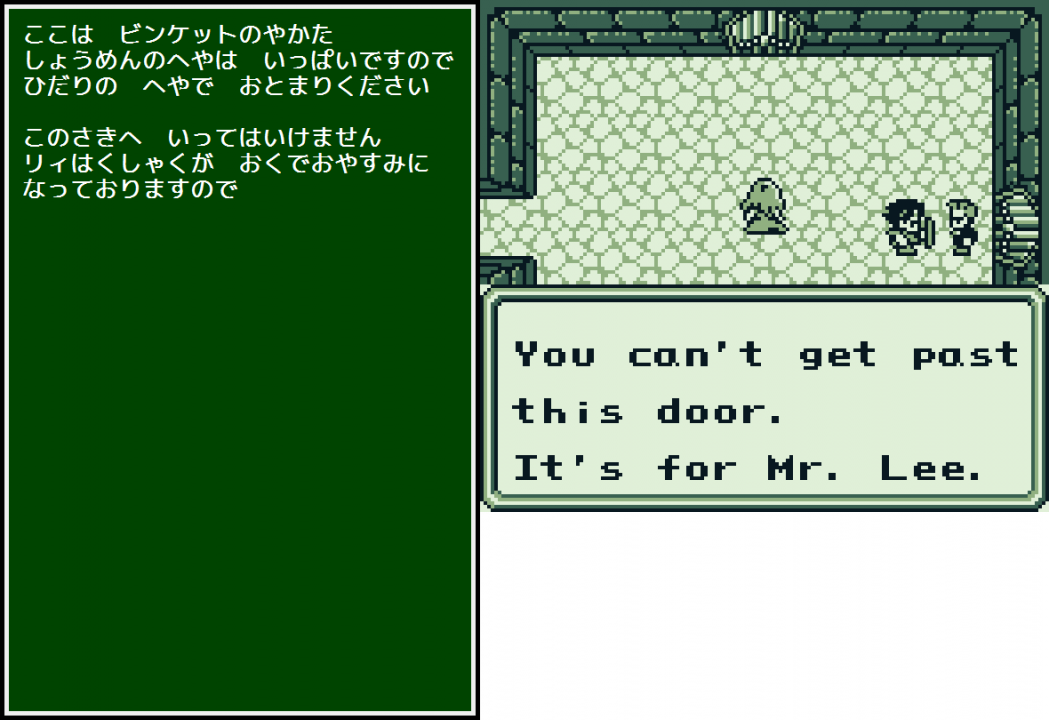

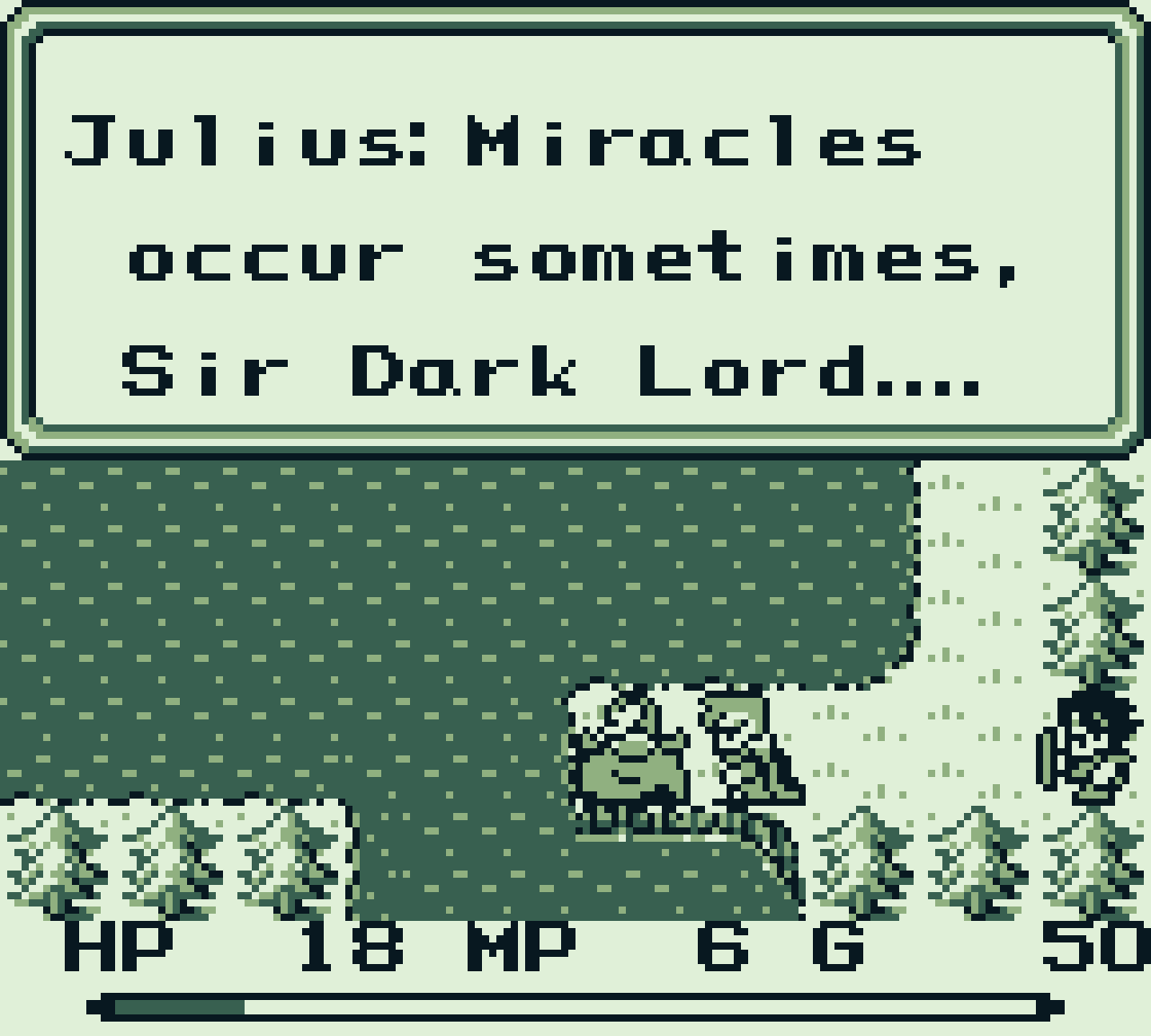

First, the owner of the mansion – who turns out to be the big vampire boss – is named リィはくしゃく (rii hakushaku, "Count Lee") in Japanese.

Next, in the English script, the mansion is called “Kett’s”. I never knew what this meant or if it signified anything, but in Japanese, it’s known as ビンケットのやかた (binketto no yakata), which can be translated as something like “Vinquette’s Manor”, “House of Binkett”, or something along those lines.

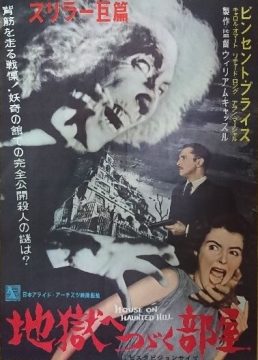

This was neat info to learn, but it still left me wondering if “Vinquette” has any significance. And then I realized that maybe it’s a misspelled allusion to another horror/thriller film legend: Vincent Price.

Of course, this is just a weak theory that came to mind as I was playing the game live on stream, but it hit me as soon as I saw the names together. I later did an online search to see what Japanese fans have said about the names, but there isn’t much about them at all. So maybe they are just random names and not references to anything, but I thought I’d share my theories anyway.

Incidentally, the GBA remake and the Vita remake both translate the name of the mansion as “Vinquette”.

Lambs and Rams

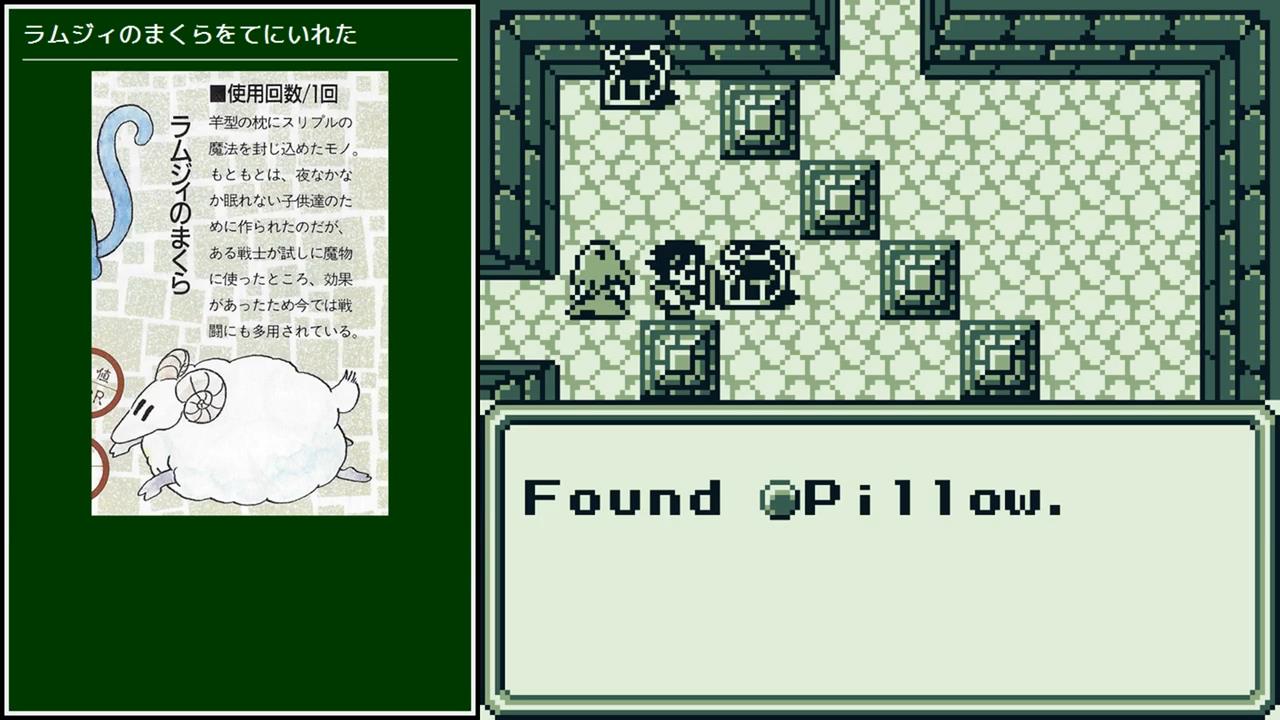

In the English version of this game, the “Pillow” item casts a sleeping spell on enemies. In the original Japanese version, it’s called the ラムジィ (ramujii). This could be translated as “Lambsy” or “Ramsy”.

When I first saw this item’s name, I assumed it was a reference to ラムヂーちゃん (ramujīchan, "Lambsy-chan"), the Japanese localized version of Hanna Barbera’s “It’s the Wolf” cartoons. Some Japanese fans think this is the case too.

Still, the item’s animation produces sprites that look like rams more than lambs, and the Japanese guide has an illustration that matches that, so I’m not as confident about that connection anymore. If anyone has more insight, please let me know!

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/bbenma.png)

Couple of little proofreading mistakes here. すくえあ is “sukuea”, not “sukea” (likewise with “sukueri”), and you called the actor “Vincent Prince” once.

The Seiken series has always been one of my true loves of video gaming. I’m excited to read more of this one.

For an even bigger reach on Vinquette, I was always reminded of another “V” word that would work in this spot: Viscount. “Vicount’s Manor” actually makes a certain degree of sense as the home of a stereotypical vampire Count. But I can’t imagine how anyone actually making a big enough spelling mistake to pull that shit off unless it was deliberate, and your theory about a deliberately mispelled “Vincent” makes a LOT more sense.

Interesting, the item that inflicts Sleep status in Final Fantasy III (Famicom) is known as ひつじのまくら. I always thought it went by the same name in Seiken Densetsu.

I figured it was called SLEP due to character restrictions in that particular menu… would SLEEP have fit? Of course, it’s pretty goofy to put it as SLEP in the dialogue box.

This is an insanely specific pull, but “Slep” always makes me think of this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kU9DKaFP5yQ where at around 8:35 Stuart Ashen reads a Norwegian article that’s been Google Translated and somehow mangled a sentence about an unsuccessful Justin Bieber concert into something that sounds more like a failed blood-ritual involving a deity called “Slepp the Idol”.

You really have to admire the level of carelessness and poor quality translation that went into Adventure of Mana’s U.S. debut. Of course the Japanese version’s script is no award winner either.

Don’t worry about falling aslep. The spell never works in Square games.

“If you were playing Seiken Densetsu when it was first released, how would you determine what the heroes’ official names were? You’d probably turn to the game’s manual and/or the game’s strategy guides.”

I never understood why someone would care. Their names are whatever you called them. Otherwise why let you choose?

How would you yo

talk about the characters otherwise? In this game it doesn’t matter much cause it’s not as plot heavy? but can you imagine Final Fantasy VII threads whwre people discuss wheather Spiky Blonde Big Sword Guy can revive Dwad Flower Girl?

Excuse u I think u mean Boyo and Gorl

Is Dragon Buster a reference to the Namco arcade game or just a coincidence?

I think it’s just a coincidence, ___ Buster is a pretty common thing in Japanese entertainment it seems.

So they changed the magic circle from a religious symbol to another religious symbol, and then changed it again into something that’s also a religious symbol.

(That square-ish magic circle in the re-release version is an Islamic symbol called Rub el-Hizb)

…So, uh, when are you going to continue FFIV?

This is great, FFA is one of my all-time favorite GB games. I must have played it a hundred times. It also started my tradition of naming female characters the inverse of my real name (with the hero being my real name, of course)

I was never all that fond of the GBA remake, though. Even if it is a bit more accurate to the original Japanese (i.e. Granz, Vinquette, Warrior/Monk/Mage/Sage etc)

Yeah, the translation is pretty damn clunky though. “Now, Glaives have her in our hands!” is such a confounding line.

@Gowtu_Games It was called Mystic Quest Legend, not Mystic Ques 61 t. The name is taken from both the Game Boy Final Fantasy games (which never made it to Europe). Mystic Quest taken from Seiken Densetsu (Final Fantasy Adventure) and Legend taken from SaGa! a.k.a. Final Fantasy Legend.

Just wanted to comment on the adding extra lines in some places and cutting them in others: this is common in Game Boy games because data is split into 0x4000 byte blocks. The original Japanese developers likely had space to spare in some blocks and not others, and so even though it looks like they are using unnecessary space, the more likely scenario is that the particular block with that dialogue had space to spare, so they used it, while other places in the script lack that luxury. Separate pointer tables are typically stored at the start of these 0x4000 blocks and so script sizes will vary in English translations based on how many lines were in the original script because the pointers to the original line in the script are usually hardcoded to those exact 0x4000 blocks.