A reader sent me an e-mail a while back about the nature of translation versus localization. I was re-reading my reply recently and thought it might be nice to share on the site too.

The Reader’s Question

I was watching Yasujiro Ozu’s ‘Floating Weeds’ on Filmstruck. […] There’s this moment near the beginning of the movie where one of the Kabuki actor’s handing out fliers for the show jokingly says he’s Kinnosuke/Kin-chan (a famous theatre actor in Japan) to a woman, but in the subtitles the English localizer decided to change the name to Toshiro Mifune when he is clearly not saying from his mouth the words ‘Toshiro’ or ‘Mifune’.

Clearly the original joke is the filmmaker’s true intention but the localized version is a reference to what an overseas audience may understand for context.

Why and how might a decision like this arise in localization and when is it okay to do and not do? Can you give examples from other games or movies?

My Reply

Hello, and thanks for the insightful question!

Indeed, there are two main approaches when it comes to cross-culture translation: take the source to the reader (make it so the reader can appreciate the translation as if it had been written in the target language to begin with, aka localization), or take the reader to the source (keep everything as-is and just assume the reader understands the source culture/language, or provide lots of translation notes on the side somewhere).

The argument about which translation approach is correct or best has literally been going on for centuries (if not longer), so it seems like it’s one of those things that will always be around when discussing translation. IMO, both approaches are valid depending on what the purpose of the translation is and what the target audience of the translation is. There is no “okay to do and not to do” – it all comes down to the unique situation.

In the Floating Weeds movie example, it sounds like the DVD translation was done with a certain target audience in mind: audiences outside of Japan who enjoy Japanese films but don’t know enough about kabuki to catch the kabuki-themed humor that was originally intended. But the creators intended this to be a humorous reference, so the translators focused on translating the intention rather than the actual words.

If the translation had been written for kabuki enthusiasts, however, the translator probably would’ve left the original reference in since it wouldn’t go over anyone’s heads. Or if the translation had been written for academics/linguists to document, a direct translation would’ve been more appropriate too. Basically, there are always different factors to consider as a translator and it’s rare that you can make everyone happy.

In truth though, as a translator-for-hire you don’t usually get to make that call yourself – your employer generally decides what the purpose of the translation is and who the target audience is. Hopefully that makes sense.

As for examples from games and movies, there are too many to count but a common thing I’ve seen in 80s/90s movies was that the brand name “Twinkie” was almost never left as-is in Japanese translations of American movies. This was because the brand didn’t really exist in Japan and nobody would’ve easily recognized the name. So various translators would replace it with “snack”, “snack cake”, “sweets”, etc.

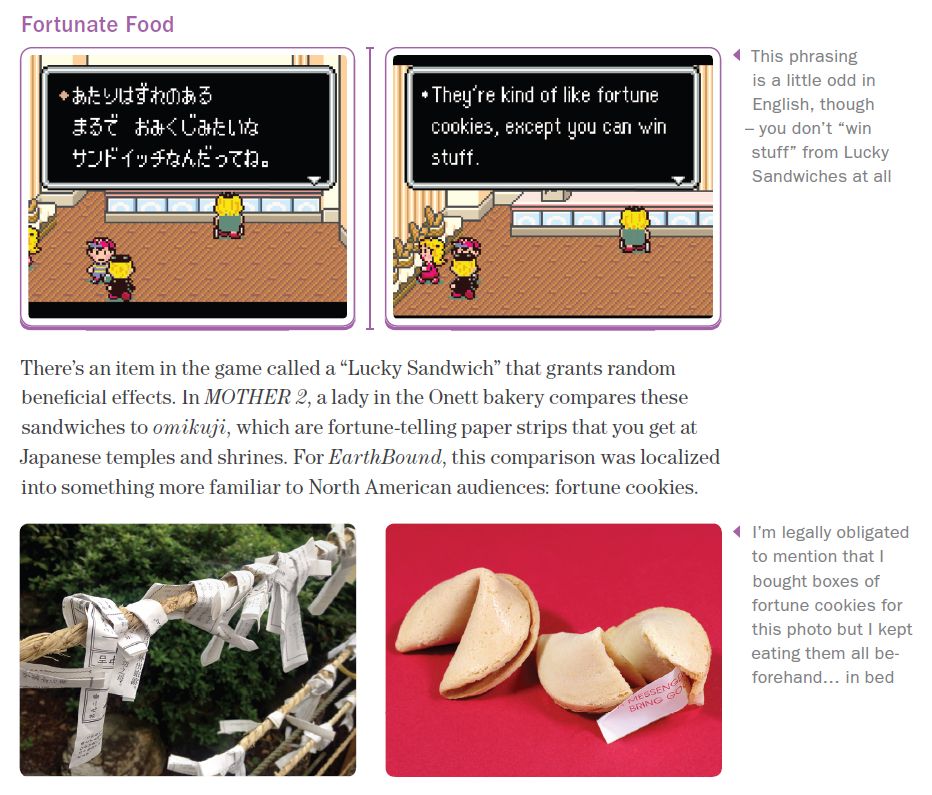

For games, one that comes quickly to mind is in EarthBound – a reference to omikuji was changed to “fortune cookie”.

Here are several other articles/write-ups that might fit what you’re looking for too, some in which references changed, stayed intact, or dropped altogether.

- ”Tomas Jefferson” in EarthBound

- Japanese proverbs in The Legend of Zelda

- An old, meme-like Japanese comedy bit in Goonies II

- Western movie references in the Japanese version of Bubsy

- Food references in Twinkle Star Sprites

- Food-related wordplay in Ace Attorney 3

As you can see in that last example, sometimes you have to localize things in games, or else the games become unplayable for the new target audience. That’s a unique part of game translation and localization not really found in other media.

Your Turn!

I’m sure there are many more examples out there of this kind of audience-minded localization. Have you encountered any in games, movies, or anything else? Let me know in the comments – I’d like to show even more examples in a future, more in-depth article about the core ideas behind translation and localization!

If you liked this light look at translation theory, check out my book about EarthBound's localization - I cover similar topics in more detail.

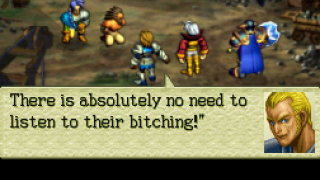

Personally, I hate when fansub videos go overboard on the footnotes, especially when it’s for stuff that has absolutely no reason to be left untranslated, like this rather infamous line: http://i0.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/newsfeed/000/037/923/keikaku.jpg

That’s not a fansub, that’s a mockup picture to make fun of excessive translation notes. Probably the most famous one, which is why it often gets mistaken for an actual screenshot from a real fansub.

No, I’m pretty sure that’s an actual fansub screenshot. And most of them are going “overboard” on purpose. It was a trend in the late 2000’s to early 2010’s for some fansubbers to start troll-subbing part way through a series because they came to believe the show was stupid, but didn’t want to leave fans hanging either. A lot of anime from this era was over the top, so there are plenty of examples of this happening.

When i posted that yesterday, I just did a quick google image search for the screenshot and grabbed the first thing i saw. So I apologize if it’s not the original authentic screen.

As for why anime fansubs do that kind of thing, the story i’ve heard was that the people running those fansub groups liked to keep things a bit too inclusive, and leaving Japanese words in like that was a way to ward off “filthy casuals”. But then, that may only be part of the reason. It’s just the story i’ve heard.

Additionally, as someone who took typography in college, i have to also point out that having an excessive amount of footnotes in an already quickly moving subtitle track can really make it hard to read. Same with distracting, animated typefaces. A good, professional subtitle track should just be a plain and simple typeface, uncluttered lines, and paced at a decent speed.

When I was younger, i will admit to watching a decent amount of anime in fansub formats, but over the years as more legal streaming services started delivering quality simulcasts with a higher professional level of quality, I’ve become more and more aware of just how garbage those older fansubs used to be. Same with manga scanslations. Now i’m at the point were i just straight-up refuse to go anywhere near that stuff.

Um… they wanted to be inclusive…so they wanted to make it less palatable to casuals shouldnt it be “Keep things from BEING too inclusive”. Is your post missing a word? Otherwise I massively agree.

This is a moving target and context dependent. Decades ago, everything was localized, even character names and the very name of the property (e.g. Macross becomes Robotech, Space Battleship Yamato becomes Star Blazers). Now, as far as I’m aware, names are always left original (or mostly so, e.g. Tien vs. Tenshinhan) and have been since probably the mid-90s. There also seems to be a sliding scale when it comes to localization where the manga is closest to the original, the anime sub taking a compromise, and the dub being the most localized, probably partly because the language might sound strange spoken aloud otherwise.

Also there is the matter of fan projects being more literal (or even untranslated) than professional localization but still with the fan-translated manga being more literal or untranslated than the fansub anime. For example, intact honorifics and pronouns are basically standard in fan-translated manga, and, including pronouns and honorifics, you’ll need a vocabulary of 50 words or so because you’ll also come across onsen, ronin, itadakimasu, ganbatte, yatta, hikikomori, and so on. Even with fan projects this wasn’t the case a decade or two ago. It’s just that the average consumer of these projects has become incrementally more familiar with the culture and some common nouns, to the point where it can be assumed.

Some other assumptions I’ve noticed with lesser localized materials is that the reader knows without explanation that characters sneeze when being talked about behind their backs, that “sorry for intruding” is a standard phrase uttered when entering someone’s home, the little girl method of speaking about oneself in the third person, and so on. Years ago there were asterisks and footnotes for these kinds of things but I don’t see them as often anymore.

As an aside, I have no idea what the localization of kotatsu, the heated coffee table with a blanket, is. I’ve never heard it referred to as anything else.

Finally, an example of a bizarre over-localization, probably already mentioned on this site somewhere, is referring to what is clearly a rice ball as a donut in the Pokemon animated series. It’s not like a wad of rice is a totally foreign concept, and it’s jarring to see something that is clearly not a donut referred to as such. The scene I’m thinking of really hammered it in; they referred to the rice balls as donuts multiple times in quick succession.

Ronin is definitely a loanword by this point, even a printed dictionary of decent size will have it. At least as “masterless wandering Samurai”. I don’t think “Someone who failed college entrance exams and is studying for next year’s exams” is that well known even among those who consume Japanese pop culture without speaking the language.

I’d argue onsen is as well. Using a foreign language’s word for that culture’s version of something being pretty normal with the obvious example being that “Gladius” is just Latin for any sword, but in every other language refers to the standard Roman sword.

I’ve also seen people say “jiang” for a specific Chinese sword when it just means sword in Chinese.

The second definition of ronin is what was in my head when I posted. Despite knowing the feudalistic definition for much longer, I absorbed the newer usage through the consumption of translated Japanese media. I’m surprised to hear onsen is an example of a commonly known loanword. I would not expect many people to know what that is.

The same goes for the word “anime.” “Anime” in Japanese refers to all types of animation (アニメ/anime being short for アニメーション/animation). However, in most other languages, it refers to Japanese animation.

A major factor in why dub translations are always “looser” than sub or manga translations is timing. The lines have to be approximately the same length in both the source and target languages, and it’s generally considered good practice to be attentive to lip flaps and any emphasis present in the animation also. If you want an example of a recent dub localization that totally ignores timing considerations, check out Xenoblade 2 on the Switch — it’s utterly maddening the way the spoken dialogue refuses to line up with the animation.

In my own experience doing VA work for dubs, I’m familiar with getting my lines along with a notation telling me how long the line is (to the tenth of a second) and what times I need to be emphatic or need to pause. To an extent, then, your actors can help to “smooth out” differences in line timings, but that only gets you so far; you can’t hand them “Watch out! (6.5 seconds, pause 2.0 – 3.5)” and get a good result no matter what. And if that’s what the script “literally” calls for, then you have no real alternative but to get a bit creative.

Haha, I was gonna bring up the whole ‘jelly donut’ thing 😛

Here’s a video of the scene if others are curious (I couldn’t seem to find a version without additions from the uploader, blarg):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2K31Hj1Oz1g

Although, speaking of Brock, I really want to know what his best line ever was in the original. Surely the pun didn’t still work in Japanese, right?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oawUi9s3ENE

Yessssss, I knew you were referring to “drying pan” in that second example. I’m curious to know the original line too!

It’s こんな時はフライパンを傘代わりに・・・ (then he notices it’s not working all that well after all) ならないな! His mouth is no longer on screen during the second bit, so I think the dub just left that bit silent.

But yeah, there’s no pun or anything in the original, it’s just a bit of random goofyness that’s treated as the goofy situation it is.

Forgot to add a translation there… the original line is basically “This is the kind of situation where I can use my frypan as an umbrella (pause as he notices it’s not working) …or not”. It’s just a silly sitcom-style situation where the joke is the idea itself and how it obviously didn’t work.

Oh heavens his best line comes from a bit later in the special where he asks Domino if she wants to “go somewhere private and line up and see if we’re a match”. I have a feeling it wasn’t HALF that filthy in Japanese.

>As an aside, I have no idea what the localization of kotatsu, the heated coffee table with a blanket, is. I’ve never heard it referred to as anything else.

I’ve always translated it as “heated table”, and I believe that’s fairly standard.

> For example, intact honorifics and pronouns are basically standard in fan-translated manga, and, including pronouns and honorifics, you’ll need a vocabulary of 50 words or so because you’ll also come across onsen, ronin, itadakimasu, ganbatte, yatta, hikikomori, and so on.

Its funny how this is a concern in the official community, and yet whenever I “corrupt” (haha) family members, neighbors, or coworkers with official manga titles where Japanese honorific usage is heavy, and more Japanese words are retained, for some reason, none of them have any problem adapting to that. (And they have no problem adapting to the fact that today, manga published in America is right-to-left.) They all seem to pick up the hierarchical nature of the Japanese honorifics. Terms like “ronin” or “onsen” don’t seem to be a problem. And if “rice balls” (a term I despise because it is so freaking wrong) is left as “onigiri,” they don’t seem to have a problem with that. After all, if you go to a Japanese establishment that sells onigiri, the term “rice balls” isn’t going to appear.

The classic example of the onigiri-donut has already been mentioned, but that always comes to mind first. But one other one is how the Ace Attorney series (originally in Japan/Tokyo) was localized as the USA/Los Angeles (or was it San Fransisco?) either way, it worked out when they first localized it, but as more games came out it got more culturally awkward to the point that they just ignore it when they can. xD

From personal experience and observation I notice that translators who pursue it beyond a hobby start literal and slowly get more comfortable with letting it “flow” and eventually completely taking liberties to properly localize. I agree that it really depends on what the target is, though. I personally prefer expressing the intent but in English that does not sound too awkward. The safe middle-ground.

Eat your hamburgers, Apollo.

http://www.awkwardzombie.com/index.php?comic=120913

Translating brand names as generic descriptions of what the product is is really common in foreign subtitles for obvious reason. If the audience haven’t heard of the brand in question, they won’t have any idea what’s being talked about.

One particular example I remember is an old episode of Friends where the Norwegian subtitles translated “sold on ebay” as “sold on the Internet” since they assumed the Norwegian audience at the time wouldn’t know what ebay was. This was in the early 2000s, so they were probably right about that.

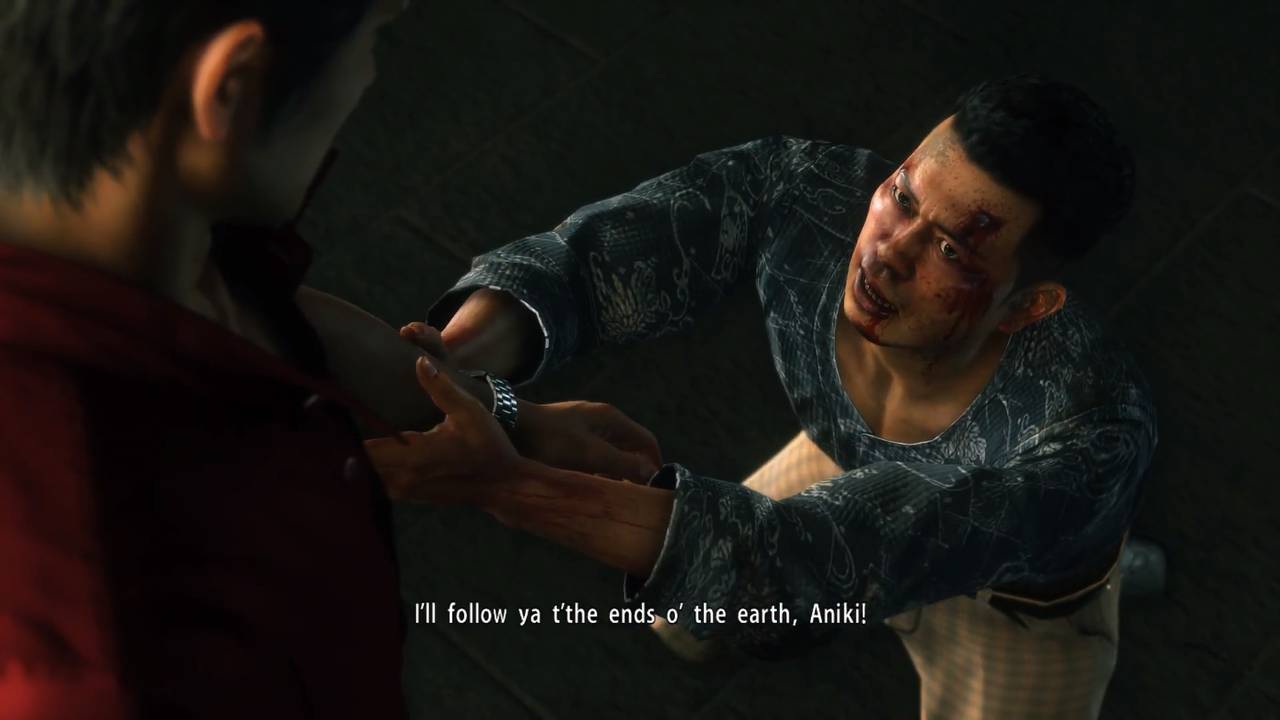

Something interesting, I’m not that far into Yakuza Zero, but as far as I’ve gotten they actually DON’T leave “aniki” in, opting to translate it as context sees fit. Was it handled by completely different people than 6?

Oh no, it’s the same people – here’s an article about that specific thing: https://twinfinite.net/2018/02/yakuza-6-localization/

This isn’t quite relating to localizing things like pop culture, but for a REALLY old example of “how much localizing text is warranted”, Martin Luther actually wrote a whole manifesto on his troubles regarding translating the now well-known Luther Bible. There’s a lot of it that might ring eerily familiar even to translators today. http://www.bible-researcher.com/luther01.html

I think the most interesting thing about it is that while Luther translating with the phrase “faith alone” is well-known as having caused controversy with the Church because of disputes over doctrine (resulting in the Catholic/Protestant split), but what’s lesser known is that its origin also comes from Luther specifically wanting to appeal to natural-sounding, idiomatic German…

“I know very well that in Romans 3 the word solum is not in the Greek or Latin text — the papists did not have to teach me that. It is fact that the letters s-o-l-a are not there…

…if the translation is to be clear and vigorous, it belongs there. I wanted to speak German, not Latin or Greek, since it was German I had set about to speak in the translation. But it is the nature of our language that in speaking about two things, one which is affirmed, the other denied, we use the word allein [only] along with the word nicht [not] or kein [no]. For example, we say “the farmer brings allein grain and kein money”; or “No, I really have nicht money, but allein grain”; I have allein eaten and nicht yet drunk”; “Did you write it allein and nicht read it over?” There are countless cases like this in daily usage…

…We do not have to ask the literal Latin how we are to speak German, as these donkeys do. Rather we must ask the mother in the home, the children on the street, the common man in the marketplace. We must be guided by their language, by the way they speak, and do our translating accordingly. Then they will understand it and recognize that we are speaking German to them.”

In ‘Back to the Future’, when Marty goes in the past, his younger mother calls him ‘Calvin Klein’, as it was the name on his shirt/underwear. In the French version (‘Retour vers le futur’), she calls him ‘Pierre Cardin’, which was a more common brand to find in France at the time. I have always thought that it was genius, and got my mind blown when I saw it in English the first time and realized the translator actually pulled that trick. That was were I decided that languages were awesome, and I should study/work in anything related to them (I am now a Senior Localization Test manager)

OK guys, I’ve a ton of examples from Italian dubs.

American treats:

-Muffins were not known to the Italian public before 2002, so dubs before that date just called them “tiny cakes”.

-Marshmallows had to wait until 2005 before their Italian debut, before that they got a bunch of weird madeup names such as “Lichen dumplings” or “Campfire candies”. The Italian translator for Peanuts notoriously made up an Italian name for marshmallows to use in the strip, “Toffolette”.

-Italians got to know what a cupcake is only around 2012, before that translators called them “tiny cakes”. Or “Muffins with extra frosting”.

Now it’s late, but tomorrow I will make a second post with more localization trivia from Italy.

I’m gonna start calling marshmallows “campfire candies” now. That’s perfect~

You forgot the two most infamous words used for a long time: Pancakes and Donuts.

It’s happens a lot when you watch the Simpsons as well american products in general, with the former translated in “frittelle” – which is slightly close being a fried dough, but the consistency is vastly different from that, more similiar to the latin “buñuelo” – and the latter with “ciambella” – similiar in shape, but is a sponge like the “Bundt cake” and not fried like the “neapolitan graffa”.

Keep in mind, lots of english-speaking movies and shows are brought to Italy since the beginning of the 20th century, therefore translations have to be easy to catch in order to understand the script fast without holding a dictionary or a thesaurus when you’re watching for entertaining purposes.

A similiar case here in Germany too regarding muffins and cupcakes. I know at least one instance where cupcakes were just translated as muffins because it was expected audiences wouldn’t know what they are. Then they became popular just a few years afterwards anyway.

Marshmallows are an interesting subject. Sometimes they were translated as “Mäusespeck” (the native German name for the candy) and in one odd instance in a Peanuts comic even as “roasted herring” but in Ghostbusters it was kept as marshmallows.

Hold up… Marshmallows are called “mouse bacon” in Germany? Or do I have to revisit my language lessons?

Yes, that’s exactly right. That would be the literal translation.

Though I don’t know if it’s because it is bacon for mice or looks like white mice.

Wow! Glad that this topic is getting some exposure here! Thanks Clyde for *localizing* this email conversation. Would love to hear more about everyone’s examples, thoughts, and feelings about these localization/translation decisions in the comments.

As for my tidbit to add to the conversation, I’ve recently been reading Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind. Surprisingly, the sound effects stylized and written out are kept intact to their original Japanese rather than appropriating with the art written out in English. There is a glossary of what the sound effects are in the back! Pretty neat but also a bit cumbersome when it comes to internally hearing the sounds. The panels themselves are drawn and structured so well that it really isn’t a hindrance. On the flip-side (literally) the now older editions of Kodansha’s English version of the Akira manga have the art flipped from right to left now and some of the text on the signage and all sound effects are translated with new fonts thereby appropriating some of the art for localization purposes. I’m almost tempted to get the new box set they put out with the unaltered art and proper reading format. It’s so odd seeing Kaneda on the cover of volume 1 holding a gun in his right hand and then in the art he’s holding a gun in his left in the art.

*left to right I meant for the art in Akira instead of right to left (the original format)… here I am making footnotes… yikes…

I like the “don’t change something unless it won’t work in the target language” approach. But even then, it can depends on what the target audience is. For instance, something like Yakuza or Persona can get away with leaving some things untranslated because most fans of those two series already have some familiarity with Japanese culture and the language. But even then, it’s a fine line to walk. As far as I’m concerned, doing something like swapping a Japanese pun for an English one is fine while straight up censorship is not cool.

The first time I saw the movie Pulp Fiction was on a VHS tape in Japan in the mid 1990s. A reference to “Arnold from Green Acres” was replaced with “Miss Piggy” in the Japanese subtitles.

I love reading about this kind of stuff!! ^_^ I want to be a translator when I grow up, and I practice when I can today, but I still have a lot to learn, and this problem is one that I think about often before translating anything at all :3 And actually, localization is part of the reason why I love visiting this page so much — I love reading about different ways to handle localization, and to make my own opinions about whether I think the degree of localization is appropriate ^_^

As for examples, I can provide a few from Danish translations:

– Donald Duck comics have always been heavily localized when brought to Danish shores. It’s been said of the ur-translator of the weekly Duck comic publication that started in 1949 and runs to this day that she wrote the ducks’ dialogue as if they lived in Denmark. A prominent example is her very creative name localizations; every character was given a unique, cartoony-sounding name that was immediately understandable to Danish audiences. A few examples: Donald Duck himself was named Anders And, translating her last name to the Danish word for “duck” and keeping the alliteration; Huey, Dewey, and Louie became Rip, Rap, and Rup, all three of which are puns on the sound ducks make in Danish; Magica De Spell became Hexia de Trick. Her first name uses “heks”, Danish for “witch”, and her last name should be self-explanatory :3 And that’s just scratching the surface of what she came up with! One of her made-up words actually made it into the Danish dictionary: “Langbortistan”, which means a really far-off place or country.

– Lots of cartoons localized puns in their Danish dubs, but of particular note to me is the Danish dub of Animaniacs. The show is packed to the brim with puns and pop-culture references, and each one was localized into Danish! Some cartoons took the approach of translating the gist of a sentence that originally contained a pun, but leaving out the punny part. That never happened in Animaniacs! I remember watching it as a teenager, knowing my fair share of stuff about the English version already, being amazed at the amount of rapid-fire puns carried over into the translation :3

– An example of localization gone goofy, however, is the translations of the word “Halloween” throughout the years. Danes didn’t start celebrating Halloween until the early 2000’s, and even then, it was a result of the general Americanization of culture. Before this time, many cartoons translated Halloween to “fastelavn”, the name of a traditional Danish holiday where kids traditionally dress up … but that’s just about where the similarities end xD Fastelavn is celebrated in spring; the kids don’t need to dress up in spooky outfits; many other activities than trick-or-treating are associated with fastelavn, and while trick-or-treating is kinda sorta a thing in fastelavn, kids usually do it at midday, not in the evening, and they usually ask for “fastelavnsboller”, a cake generally only served during fastelavn.

That was all from me! :3 Thanks again for writing on about translations ^_^

The last bit reminds me how an earlier Italian translation of Carl Barks’s comic adaptation of the Donald Duck “Trick or Treat” short, made when Halloween was totally unknown in Italy, tried to pass the whole costumes and witches and stuff for a Mardi Gras party themed around the Devil.

Halloween was translated as “carnival” in Norway. Just like with your fastelavn translation, it didn’t REALLY make all that much sense, but we kinda just shrugged and went along with the provided idea that in Duckburg carnivals apparently involve begging for candy from strangers. It’s not like we had any idea what Halloween was.

I also remember that one Barks Thanksgiving story where Donald goes hunting for a turkey dressed as a pilgrim got a translation that tried to act like this was a Christmas story. Turkey isn’t all THAT associated with Christmas here, but nobody would know what “Thanksgiving” was, so they had to change it to something.

Really interesting stuff! And especially how different countries localize Halloween. I’d love to see a list of how different countries translate/explain/localize very American holidays like that.

As in Sweden about Donald Duck. He’s called Kalle Anka, same thing with anka=duck.

But Halloween was in our version and they explained straight about what it is about so we knew already about Halloween.

But we do have almost similar tradition for this. Don’t know if it still practised toady. Children both boy and girl dresses to Påskkärringar (Easter egg hags/witches) and begs for candy in neighbourhood. But they do not do any tricks if they is declined for candy. 🙂

Also the known swedish Donald Duck translator also made up many funny words and Onomatopoeias which only uses in Donald comics as Flämt, stön etc. It seems Langbortistan (Långbortistan) was used in here too!

Some named is funnily renamed as Beagle Boys became Björnligan (The Bear Gang), trough they did not look like bears.

Many things can it be written about the Swedish traslation of Donald Duck. So I did tried maked this short. 🙂

These comments were about translations done in the early 90s and earlier. Modern day Norwegian and Danish translations just use “Halloween”.

So, I’m back for some more things about Italian localizations.

-The Christmas episode of The Simpsons Season 11 had a brief scene of Krusty presenting a special with tons of guest stars. Since most of them are basically unknown in Italy, they replaced them with more known ones. I don’t remember most of them, but the one that stayed more in my head was that they tried to pass off the Dixie Chicks as the Spice Girls. Like, the Spice Girls were 5/4 with only one of them being blonde, and the Dixie Chicks were 3 blondes, so anyone could tell that these were not the Spices.

-An episode of Family Guy had a scene of Peter meeting politician Dick Armey and laughing because his name sounds like “Dick Army” and asks him if his wife is called Vagina Coastguard. Since the joke would be lost on Italian audiences, they renamed him Dick Hudson, which sounds like “Dì cazzo” (Say Fuck) and Peter asks him if his wife is called Tess Tickles.

Trying to think of some examples of local uh, localizations… I believe Egon’s Twinkie was translated as “panecillo” or “pastelito” (literally, a snack cake.) Twinkies were not a thing here, we have a similar snack cake called “Submarinos.” Basically the same thing, just not as full of corn syrup.

I wish I could remember more examples. I used to watch a lot of translated / dubbed movies when I was a kid and I always read the subtitles, that’s how I realized a lot of folks in my day were very creative when doing their thing. Not like today. Mexican translators just piss me off now…

When it comes to localization (a term to me that basically has come to mean, “Get rid of that filthy slant-eyed stuff and replace it with superior, Western stuff.”), I often feel that official publishing houses (whether manga or anime) want to make things more Western than they should. When it comes to an anime dub, I could care less how much they Westernize it ’cause I don’t watch Anime in English. But when it comes to the subtitles, I want to know what is actually being said. That being said, I realize (after getting to know and talk to translators like Mato over the years) this is a tricky thing.

Back when fansubs were more of a thing (most titles for download today are just using the official streaming subtitle scripts), I do think that fansub groups could go a little too far in not translating things and making long translator notes. But at the same time, because they did this, I gained an education and insight into Japanese culture that I wouldn’t have done if something were simply “localized” and who gives a rat’s rear about what was actually said.

Before “Those Who Hunt Elves” was licensed by ADV, I downloaded the fansubs. In one of the episodes for the second series, the group learns of a mountain and decide to travel there because of the name. The fansub group translated the mountain’s name of “Kamisan” as “Mount Kami (kami means god)”. So based on the rumors about Mount Kami, the core characters are hoping to find some god-like entity who can send them home. When they get there, they discover there is no god, only little white teddy bear creatures who literally crap rolls of toilet paper. So instead of “kami” meaning “god,” “kami” actually meant “paper.” And the fansub group had a tiny note similar to before about Mount Kami (kami also means paper).

When I bought the series from ADV, I was highly disappointed that the official subtitles didn’t take this same approach. Instead, the decision was made to localize things in favor of a stupid joke and to hell with how this impacted the story. Thus, the group sets out to Mount TeePee ’cause “reasons.” It didn’t make sense that a mountain called TeePee would support the rumors that caused the group to head there. Then when they get there, they all laugh ’cause of the teddy bears crapping toilet paper and realize the name of the mountain is Mount T.P. Yeah, ’cause we always name mountains with initials. “HAHAHAHAHAHAHA! No, that’s not a fake laugh. That is the most real, authentic, hysterical laugh of my entire life!” *_* In this instance, I felt the fansubs did a much better job of things.

You bring up a good point that we could be taking the (arguably excessive) annotations for granted. I retained a good amount of the information from the era you’re talking about and didn’t need certain things explained to me subsequently. Context matters, though. Annotations can be very awkward in a timed medium like anime but usually doesn’t seem out of place in manga unless the translator is excessively verbose or editorializes.

In a German Calvin and Hobbes book I came to find, I was ever so proud of myself for being able to read a pun they had altered. In the original, Calvin can’t decide what to collect between stamps or bugs so he raises his foot over an anthill and says he decided on “stamped bugs”. In German, he says pressed flowers or bugs, and decided on “pressed bugs”.

The manga Excel Saga has a lot of translation notes. One that sticks out to me is how at one point, Excel beholds some fast food mascots being washed away and she remarks on one of them. In Japanese she refered to one that foreigners wouldn’t know, so in English it was changed so that she remarked on the Cnl Sanders one next to it. What was fun about that is that it was already there in the shot.

I recall there was some sci fi movie in the ’90s that did this overseas. I can’t remember the movie! But there were ads for Taco Bell, and those were changed to other companies for foreign releases.

In Digimon Data Squad, there was an episode about manjuu, and the English dub CALLED it manjuu, and even captioned it with the two Us in it…but took out the text on a sign of a shop selling it! You could even TELL something had been removed since the edit was supremely terrible. But why leave in such a very specifically Japanese treat and then erase the text?

The movie you’re thinking of is Demolition Man.

One thing that I think doesn’t get mentioned enough when talking about localization is the age range of the target audience. I mean, the old 4kids Pokemon dub gets made fun of a lot for its admittedly terrible onigiri edits, and yeah, most people you’ll ask nowadays have a general idea of a ‘rice ball’ being a common Japanese snack, but how many 6-year-olds in the 90s would have known that? My first-grade self would’ve been just as confused by the concept of eating a ball of rice as I would if I saw someone calling one a donut, and ultimately it’s so irrelevant to the story that I wouldn’t expect them to put in the effort to provide all the necessary context to an elementary school audience who probably doesn’t care.

It’s the same thing with most dubs and localizations of media that include younger people in their audiences. It’s why I’m much more accepting of excessive localization in kid-friendly franchises like Pokemon (I’m honestly impressed by some of the localized species names!), as well as anime dubs that’re expected to be watched by elementary- to middle-school aged kids, while with stuff aimed more at teens and adults I’ll generally expect at least the broad cultural references to stay intact. It’s also probably part of the reason anime subs are less localized than dubs (besides the timing problems) – the dub format is friendlier to the younger and/or more casual members of the audience and more likely to make it onto more mainstream platforms like TV, and thus the actual content should also probably be more accessible.

Of course, even with kid-friendly franchises there’s a fine line between localizing and dumbing it down unnecessarily, and different people have different opinions of where to draw that line, but I do think it’s an important consideration. After all, we tend to group up with people with similar ages and experience levels, so it’s easy to forget that not everyone has years of exposure to pop culture to help them figure out that yes, people in Japan do make balls of rice to eat on the go (and they’re actually pretty good)!

How would a kid find a ride ball confusing? Everything you need to know is in the name. It’s a ball of rice. It explains itself.

It’s worth noting that the entire reason most Europeans know what stuff like Halloween and Thanksgiving even is is because movies, comics and TV show translations started just calling them what they were and let people work out the concept through context instead of just calling it “Christmas” and hope people wouldn’t wonder to loudly why these people celebrated Christmas in such a bizarre and un-Christmasy way.

Pop culture can be educational and kids in general are a lot more receptive to foreign concepts than they tended to be given credit for.

Hmm, I guess my intent with the onigiri example wasn’t quite clear enough. I was more thinking of minor background details rather than bigger concepts. I guess the difference is the amount of context provided: if a story takes place over Halloween, it usually includes a bunch of examples of how it’s celebrated – kids dressing up, spooky decorations, candy – enough that people can get a general idea of what the holiday is, even if they’ve never heard of it before. But for more isolated stuff, like the onigiri in Pokemon, there’s no real surrounding context to give someone the idea that it’s a Japanese food. The setting is generic enough that someone watching wouldn’t necessarily expect it to include Japanese culture, and there’s no additional context provided to help you reach that conclusion. So, while someone who already knows that a) the show is Japanese and b) rice is a Japanese staple should be able to figure out that it’s a minor cultural reference, someone who doesn’t know this probably won’t understand WHY these characters are eating what appears to be plain rice. And the show itself doesn’t provide any additional detail to help elaborate on this, and ultimately it’s kinda irrelevant – each rice ball mention lasts a couple seconds at most, and the fact that it’s a rice ball specifically instead of some other food isn’t really important (as far as I can remember…) so they don’t really gain anything by keeping the reference in.

I should probably also note that I don’t agree with the amount of Westernization in old 90s dubs (I do think they went overboard), only that I can understand why they chose to do it. A certain amount of context is needed to understand references to unfamiliar cultural concepts, and kids just don’t have as much prior knowledge as adults, so they’d have a harder time deciphering these references if the show doesn’t provide said context for them. I’m not advocating for kid-focused translations to wipe all foreign cultural references entirely, just saying that translators have to be a bit more careful about making sure those references are given enough explanation in the text itself instead of expecting their viewers to already have the necessary experience to figure out what they mean – or, if the context isn’t there, changing the reference to something easier to decipher.

It’s not “westernization” – as has been pointed out in various comments here, the entire world was doing this. The American Pokemon dub was going “Rice balls? American kids won’t know what that is, call them donuts” at the same time the Italian Simpsons dub was going “Donuts? Italian kids won’t know what that is, call them ciambelle”.

It’s become less common these days because translators are starting to catch on to the fact that kids take things at face value. If you call a donut a donut and the kids don’t know what it is, they’re not going to scream in panic and turn off the scary program, they’re just going to run with the fact that it’s some kind of food they haven’t heard of. Little kids aren’t going to be familiar with every single word and term they hear on TV anyway no matter what, and the kids themselves KNOW this. Kids like learning about new and unfamiliar things.

If you have to make sure everything mentioned in your kids’ show is something every kid in the entire country is going to know what is, you’re going to end up with very boring TV.

I actually completely agree with all this, I just think I’m approaching it from a different direction! I’m not arguing that translators should, say, pretend a character in a kids’ anime is doing something else if they’re shown visiting a shrine on New Year’s, only that they should make sure to mention the connection between the holiday and the shrine visit instead of assuming their viewers already know about it. Just adding a line like “hey, it’s New Year’s, let’s go visit a shrine!” where there wasn’t one before helps kids figure out what’s happening without changing or removing the reference.

My point was more that kids’ media translations should include more context clues because their audience has less prior knowledge. Adult-targeted translations can get away with less, because chances are an adult watching subbed anime on Crunchyroll is already familiar with the idea of New Year’s shrine visits and will make that connection more easily. Kids don’t need things spelled out for them; they just generally need more information than adults in order to get to the same conclusion.

So I remember watching this episode of the Osomatsu-san anime, and there was a sketch where Jyushimatsu set up a stand over at Comiket to sell “BL” doujinshi, which turned out to be actually “baseball” books, much to Choromatsu’s chagrin. The joke being that he was describing innocuous roles in playing baseball with terminology that more evokes the feeling of the “boys love” genre (hence “BL”).

Now, for whatever reason, Crunchyroll’s subtitles for that very scene opted not to translate half of the terms that Jyushimatsu used (“What about this? Catchers are total ukes”, “This is an outside uke’s screwball seme” “Well, what about Super Seme-sama?”), thus making the joke completely incomprehensible to people not familiar with either the Japanese language or the specific “boys love” genre. Crunchyroll didn’t add any helpful “translator’s notes” to Jyushimatsu’s lines for the beginning anime watcher either, making the joke even less sensical. You’d think that Crunchyroll would at least translate “seme” and “uke” to similar English equivalents and have Jyushimatsu word it so intentionally awkwardly so a similar joke to the Japanese script would carry across. Because Googling “seme and uke” would bring about some rather unsavory NSFW results for the unprepared and weak willed. And I know that if that scene were ever officially dubbed into English, the “English equivalent” approach to translation would definitely have to be taken out of practicality.

This article definitely gives me more understanding on why things like that happen in translation. Very insightful.

I didn’t clarify this last post, but “seme” (攻め), super-literally meaning “attacker”, has the connotations of either “top” or “dom”/”dominant” in the context of BL. Uke (受け), super-literally “receiver”, means “bottom” or “sub”/”submissive”. The Japanese terms are exclusive to boys love only, not any other gender combination. So basically a similar joke that plays upon the “accidental” innuendo would be that “Catchers are really submissive”, “This is an outside sub’s screwball domination”, etc.

It’s pretty clear that Crunchy’s subtitles were translating under a pretty tight schedule with a ton of other anime on board, so maybe they just didn’t have time to refine the script for that joke.

Oh, and here’s a rather interesting example: The Netherlands have produced Donald Duck comics where Donald and friends celebrate Saint Nicholas Day for ages, and it shouldn’t come as a huge surprise that these have always been written by Dutch writers for a Dutch audience with absolutely no intent of ever getting published in other countries. For the most part these have stayed in the Netherlands, but there’s one story that actually did get published in a number of other countries as well:

https://inducks.org/story.php?c=H+85212

I’ve never read it, but considering the international titles translate to, respectively, “Dutch Christmas in Duckburg”, “Saint Nicholas is not Ungrateful” (I think, I’m not all that good at French), “Saint Nicholas Visits Duckburg” and “Christmas, Dutch Style”, it’s pretty clear it was just translated as is instead of being heavily rewritten to turn Saint Nicholas into Santa or something like that. This was way back in the 80s, too.

A philosopher’s perspective:

The most ideal sort of translation would be the one that’s most faithful; by faithful, here, it means it’s able to properly convey the thoughts behind the work to the audience within a manner that allows them to perceive the original thought clearest.

Changing stuff, even for the purpose of clarity, must always be done with care, since then, you may not be conveying the original thought. That sort of practice can only be done if it’s not vital for the thought’s proper existence; in other words, if the thoughts behind the work depend on its existence in order for t to be itself. However, at many times, you’d be surprised as to what may not be so; that Kabuki theatre actor thing, for instance, the specific name of the famous actor is surprisingly not vital for the joke to be gotten across, so changing the name won’t effect the projected thought in a manner that causes it to not be itself.

That violin example, that violin quote from the book, it speaks of the “representative” sort of mindset, in which the violin is seen as a representation of the original message. Its rationalization about how it can’t mimic the same message as the song about the piano, however, is only half-true; what if I tell you it’s possible to convey the exact same message on the violin as what can be conveyed on a piano?

The trick is to know, whatever conveys the thought is not whatever it is they convey. It’s how you see the projected thought that matters most, more so than anything else. The only times where technical details, such as how a musical instrument works, ever matters is when they are vital for a thought to be itself, but even then, thoughts are still independent, seperate from any building blocks used to build them.

It’s through this logic that a completely faithful translation can be achieved, perhaps one that even seems to have more thought put into it than within the original language, depending on the sitation. Translation is, as with all artforms, a projection of thought.

Despite the immense logical sense this whole article makes, even if you were to show this entire explanation to ignorant sub-loving idiot weebs, they would still say English localization “ruins everything”.

Some people just need to see the whole picture from a new angle to revise their views on things, so if this article helps a few people understand the difficulties of straight translation then it’s improved the world a tiny bit. There will always be people who don’t look beyond their pre-held notions though, so it’s not worth getting upset about them and insulting them. If anything, that’s probably a recipe for pushing people away.

Check GameFAQs and YouTube for said examples of those types and you’ll see what I mean.

I guess I’m the only person who would prefer more localization these days, and not less of it.

Sadly, with the Internet, the trend is to keep everything as close as possible to the original source, even when it makes little sense in English.

I’m with you on that. Not everything translates perfectly across languages so some liberties have to be taken.

I recently read Natsume Soseki’s “Kokoro”, and there were some spots where it felt very odd.

It referred to two people, both men, as putting on their “summer dresses” at one point. From context, the original was almost certainly “yukata”, but the translator assumed Western readers wouldn’t know what that was. Why they went with “summer dress” instead of “robe” I have no idea though.

At another point, it had two people playing “chess” (whether it was originally Shogi or Go I couldn’t tell) who put the board “on the table on top of the foot-warmer between us”, which flummoxed me for a minute until I realised that they were sitting around a kotatsu.

That’s an interesting situation. If you’re going to translate that, I don’t think “summer robe” is even enough because that seems even more obtuse than just leaving in “yukata”, a word that is in some English dictionaries. I brought up kotatsu before because I hadn’t seen translations of it. I figured attempts would be as awkward as the above, though I’ve since been told that “heated table” is somewhat common.

“Summer dress” sounds a lot like somebody figured out what the closest garment in generic Western culture to a yukata is (in terms of both shape and associated casual formality) but forgot the part where men were doing this rather than women.

I’d ask why translate it at all, let alone like this, when the adult audience for a Japanese novel written by somebody other than Murakami is probably going to have better Japanese cultural literacy than children, when novels have the most visual freedom for footnotes. Apparently it’s a 90s translation, though, so who knows.

Personally, if I had to, I would’ve shot for “summer jackets”.

In pervert superhero parody movie Hentai Kamen: Abnormal Crisis, there’s a scene where the villain, who’s now just a disembodied head because of what happened in the first Hentai Kamen movie, has just gotten his new body. In the original Japanese, he complains that it’s not up to specifications because he had wanted a body in the style of a boy band rock star. But in English he complains because he wanted a body that looked like Thor.

Years later this particular translation still bugs the hell out of me. Without knowing anything about the Japanese music scene being referenced I thought the villain’s desire to look like a sexy boy band singer was hilarious. It’s just so counter-intuitive the way he explains the specific details he was expecting in a patient, deliberate tone of voice that matches his character. The Thor reference, by contrast, was utter garbage. It’s not funny. The villain’s whole design is that he’s brains over brawn, which clashes with the reference and doesn’t make sense with his new explanation. But worst of all, Thor’s just barely a mainstream enough reference that people not familiar with the original translation might not realize it was adapted at all.

This is why I tend to prefer the taking the reader to the source school of thought rather than the source to the reader, and to use generic references in cases where taking the reader to the source just isn’t practical. Maybe it’s just because I’m an American but I find there’s a very frustrating kind of narcissism in English language culture that just assumes our references are everybody’s references. The often extreme difficulty of finding any non-English language material in American media at all often amplifies that. It’s no wonder that fan translators have such strong opinions on the subject. They typically got into the hobby because they were interested in foreign cultures and wanted to provide more exposure to them. From that context any kind of referential translation that tries to deliberately play down foreign elements is completely missing the point of the aesthetic value of such works to a foreign reader.

This article got me thinking about the anime Aggressive Retsuko. The original shorts never got an official translation, so as a result they got a fansub, and one of the best things about it in my opinion is what they did with the character names. The characters are all anthropomorphic animals whose names are puns on their species (a hippopotamus named Kabae (“kaba” meaning “hippopotamus”), a spotted seal named Gomakawa (from the spotted seal’s Japanese name, “gomafuazarashi), etc.), so what the translators did was change the names to Western-sounding ones that also made sense as puns in English (Kabae became Hippatricia and Gomakawa became Lucille, for example). The Netflix reboot, on the other hand, used the Japanese names for both the sub and the dub, meaning the puns in the names were kinda lost when translation happened.

I prefer translation with note, this also help me know more japanese word compared to localize version that mostly already altered and the culture is changed.

they just need add small note for pun and translator not need to think so hard how to alter it anymore.

example about akuma pun, ‘A’ wanted to look like a demon and ‘B’ giving ‘A’ a bear costumes.

Pun : あっくま→A’h’ Kuma(Bear)→悪魔(Akuma/Demon)

I am fine if they change it in english dub but for sub better keep in original because they can add note.