During my career over the years I’ve learned that certain things come in waves in the professional world. For example, freelancers might experience a feast-or-famine cycle in the work they receive. Among writers, there’s a cycle of getting the spotlight and struggling to get the spotlight. But there are two other types of cycles that are more general and affect a wider group: confidence and skill.

Basically, when you take the leap into the professional world, sometimes you’ll feel very confident about your skills – especially just as you’re starting out – and then a little while later you’ll begin to feel doubt about those skills. And then after doing some work, you’ll eventually feel confident again, only to run into something that makes you feel less confident again.

Branching off from this is another pattern concerning skill itself: sometimes you’ll feel very confident in your work and think you can handle anything. Then a new project comes along that kicks your butt and teaches you that you knew nothing. But it also helps push you to a new level… where the confidence and skill cycles begin again. But with each cycle comes the potential to improve and grow.

I think this might actually apply to anyone learning a new skill or art, not just professionals. In any case, it’s important to acknowledge these patterns and never stay too long on that plateau of complacency. Otherwise, ego begins to take hold and you’ll never grow.

|

A fellow writer and translator sent in a short article about his own experience with this phenomenon, and I thought it would be nice to share as a real-life example of these things in action. Give his article a read, and see if any of the general wisdom could be applied to your own situation or career!

Humility Is a Translator’s Ultimate Weapon

No one tells you how to be a translator. There’s a handful of schools in the United States that will impart on you the basics of the translating profession, but learning how to deal with customers who believe they know more than you do and keeping clients happy and coming back are the kinds of skills that are difficult to provide to a classroom full of sleepy, strung-out college students.

Among the hidden personal skills translators must learn is the secret art of humility. Translating tends to turn into a matter of pride more than once per job, and if you want to see a paycheck, you’ll need an iron gut to process some of the more ridiculous requests from your clients and proofreaders. It’s a struggle of picking battles. But you can learn through translation when to set your pride aside and realize that you have a thing or two to learn from the people who depend on you.

Learning When to Learn

I’m a generalist when it comes to translation, which is probably the least lucrative direction to head when trying to make a living as a Japanese translator. But the draw, for me, is that I get to translate in any of the fields in which my peers work. One of the cooler translations I’ve had the pleasure of undertaking was a comprehensive menu for a classy Nagoya restaurant that I won’t name here – but you can probably find it easily if you know what to search. Their selling point is a menu packed with foods that are all fermented to create rich sour and umami flavors that they then infuse with common Japanese foods.

Like most translations as a generalist, taking on the unusual vocabulary in this job meant swapping screens between my dictionary and the menu every couple of minutes. When the vocabulary is overwhelming, you start to confuse ideas and have to organize your thoughts with intense concentration. With no shortage of focus, I was able to complete the translation to a level I believed to be one of my highest yet, especially considering that the subject of fermented foods is so specialized and specific.

Then, I got my corrections back in deep red from my translation coordinator.

“This is not the intended meaning of ‘koji’”

“Do you mean to say that the food is organically grown?”

“I don’t think that word means what you think it means.”

Comment after comment was brutally attached to my work of art subtly reminding me what an inept translator I was. My initial reaction was fury, followed by resentment, dark thoughts of revenge, and then a moment of peace. I recalled what one of my Japanese mentors repeated in earnest nearly every day – “The day I have no more Japanese to learn will be a sad day, indeed.”

Understanding the Value of Humility

I reevaluated what it meant to be in my position as the main translator. I had already successfully completed countless translations in advanced technical fields before with only a handful of corrections at most, and I had come to expect a high level of performance from myself. However, I quickly came to a gross realization that I had been receiving money to produce half-baked translations that I was doing on tired nights after I finished my full-time work for the day. I was holding on to pride that I hadn’t earned, and it was time for a big change.

I approached the corrections full-force with a renewed sense of duty. If I didn’t want to be a permanent internet joke (“all your base are belong to us,”) I would have to allow my translations to undergo the type of scrutiny that demanded perfection. And that’s when everything changed.

A New Translator Is Born

I made the corrections posed to me, compromised on some grammar and phrasing, and even took a few extra stern looks at the work I had put together to find the holes and rough surfaces that needed filling and polish. The result was pure translation magic – and I can take pride in the draft that I sent to the restaurant. They took a few liberties on my final draft and their English menu now contains a few errors worth a chuckle, but to me, it’s only a sign that I didn’t do my job the way I was supposed to do it.

Learning that humility is a part of my work on that day created a gigantic wave of change in the quality of my translations. It shows in each translation I’ve performed since then, and the bigger my jobs get, the more intent I become to make the current one the best one. It seems like an easy lesson to learn, but it takes a harrowing experience like mine to really learn what people will continually tell you: Learning a language never stops.

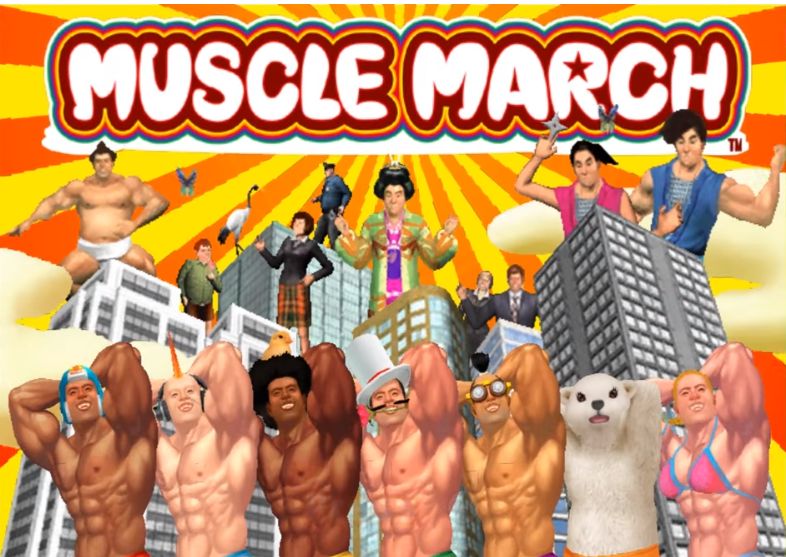

Translation is a high-visibility profession, and every translation job is a risk. But when you pull it off, it comes with a remarkable feeling of accomplishment. Congraturation, this story is happy end. Thank you.

Eric Ysasi is the owner of Austin, TX based translation enterprise and blog Kuma Language Services and works on general translation in news, technology, and the arts.

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/pressstart.jpg)

Freelance life sounds tough!

I can certainly agree with Eric’s words. I know I had a lot to learn going into English teaching and I accepted every bit of criticism I got in order to improve my lesson plans to the point my lessons were both fun and comprehensive for the students. We’re a constantly learning race of beings; gaining a better understanding of everything and anything is in our nature. If we do truly stop learning one day, then I guess we’ve reached the top. Doesn’t mean everyone would be happy about that.

One thing that weirds me out is when I know my work is flawed in ways that other people don’t pick up on. That leaves me in a sort of uncomfortable limbo where I really want to improve it, but I’m concerned that, if I do, I’ll just end up breaking something else in the process. It’s much simpler when everybody agrees that something stinks. 🙂

As a sort-of example, just the other night I was working on a new rope trick, and I showed it to the wife to see what she thought, and she was floored by it — just completely taken in. Meanwhile I’m thinking I know for sure I tipped at least three times. It creates a sort of uncertainty that is, in a way, much worse than just knowing for a fact you’ve done it wrong.

Thank you for sharing this… it hits a little close to home indeed. Though I wish I felt anger and resentment rather than just pure sorrow and embarrassment when things go wrong, I do learn and grow with every mistake that comes a long.

It is nice to know that it was not just me, however, who isn’t able to come in and do things perfectly from the get go.

Always an inspiration as always!

I believe you can avoid this cycle and, at the same time, not give in to pride simply by doubting the perfection of your own work instead of yourself. It’s unrealistic to ever consider the possibility of your work being 100% perfect. Even the best works has things things the creator may want to improve.

Since it’s impossible to get rid of your feelings, the best thing to do is to reconceptualize them as to make them not detrimental to your art. In this case, the best thing to do would be not to doubt yourself, but instead, know that you’re imperfect and doubt your own work instead. I don’t think even the Japanese themselves can be called 100% masters of their own language (the same way we can’t consider ourselves 100% proficient in English).

Also, don’t fear failure. Instead, embrace it as something good and see it as the means of finding out the truth.

I believe the only reason why people only think it’s a bad thing is because people fear it, their dislike for failure also being the reason behind it getting into their heads.

So, have you ever been to Final Fantasy Wiki? That place is an excellent source for checking the various translations of terms and such between Japanese and English. Now, I do have a question though. In the fifth ark, some of the location names feels a little odd. Some locations names such as ナルテックス (narutekkusu) and ミドル・クロッシング (midoru kurosshingu) are fairly easy to get but what in the world is クワイア(kuwaia) supposed to be? Or サクリスティ (sakurisuti) for that matter? Reading katakana can be a pain after all…

クワイア(kuwaia) sounds like how a Japanese would pronounce “Choir” (as in the singers), while サクリスティ (sakurisuti) sounds similar to “Sackristi”, which not only do I think that’s neither English nor Japanese, I also don’t know if I transliterated it correctly.

「クワイア」 is definitely “Choir”.

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%AF%E3%83%AF%E3%82%A4%E3%82%A2

As for 「サクリスティ」, it could be “Sacristy”:

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%81%96%E5%85%B7%E5%AE%A4

These are all based off of religious architectures:

アッパー・アイル = Under Aisle

ロウアー・アイル = Lower Aisle

インナー・アイル = Inner Aisle

トップクロッシング = Top Crossing

ミドル・クロッシング = Middle Crossing

アンダー・クロッシング = Under Crossing

ディープ・クロッシング = Deep Crossing

ナルテックス = Narthex

ネイヴ = Nave

クワイア = Choir

シントロノン = Synthronon

プレスビテリウム = Presbyterium

トランセプト = Transept

サクリスティ = Sacristy

アプス = Apse

Thanks! Katakana can really mess up your mind sometimes. Still, do go ahead and search Final Fantasy Wiki for interesting translations. By the way, both Narthex and Nave were used for location names in the english version too but in different locations. Narthex in Orphan’s Cradle and Nave in Pulse Vestige.

And the Pulse Vestige names by the way appears to be Shinto inspired in the Japanese version by the looks of it. The first area is Haiden for example which is one of the many buildings you might find at Shinto Shrines.

クワイア sounds a lot like “choir” to me. In fact, that’s what google translate says that it is.

No idea on サクリスティ, though.