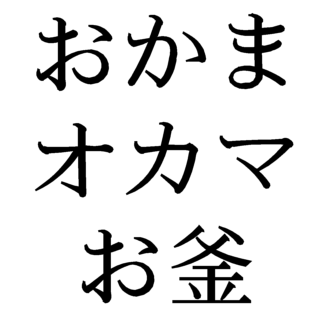

This time, we’ll take a similar look at something that’s both tricky and controversial: the Japanese word okama.

Along the way, we’ll also briefly examine the multiple meanings behind the word okama, as well as its different uses in Japanese media. We’ll then look at how okama has been translated into English in a variety of video games since the 1990s, and then use some detective work to see how use of the word okama is now changing in Japanese entertainment itself.

Meaning of Okama

You could literally write entire books about the Japanese word okama, its centuries-old origin, its evolution, its modern connotations, and more. But the quick version is that okama can refer to a bunch of different things, including homosexual men, transgender women, and crossdressers.

For reference, here’s how different Japanese-to-English dictionaries define okama. The first three are standard dictionaries, while the fourth one is more of an English-to-Japanese slang-oriented dictionary:

| Dictionary | Definition of okama |

|---|---|

| JMDict | male homosexual; effeminate man; male transvestite |

| Shogakukan Progressive Japanese–English Dictionary | a (male) homosexual, a gay (man), a fag; a queer |

| Kenkyusha’s New Japanese-English Dictionary (Fifth Edition) | a gay; a queer; a fag; a faggot; a male prostitute |

| Eijiro on the WEB Pro | agfay; fag; flaming fag; flaming fruit, fruitbar; fruit; fruitcake; queen; queervert; shirtlifter; sister boy; sweet; sweetie; swish; twinkie; twinky |

As we can see, okama is a mostly negative and derogatory term. In some contexts, however, it’s used as a neutral term or as a positive self-identifier.

Okama in Japanese Media

Dictionaries are one thing, but real-life usage is another. Here are a few representations of okama in Japanese media:

In short, okama has a variety of meanings and is usually negative, but not always. In addition, like most words, its meanings, connotations, and depictions can change over time.

Okama in Translation

There’s no single English equivalent for the Japanese word okama, yet it appears often in Japanese entertainment. I’ve seen it handled many different ways in English game localizations, so I thought I’d share some of my findings below.

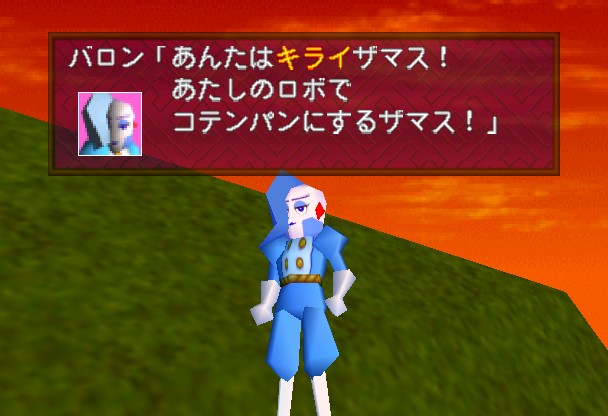

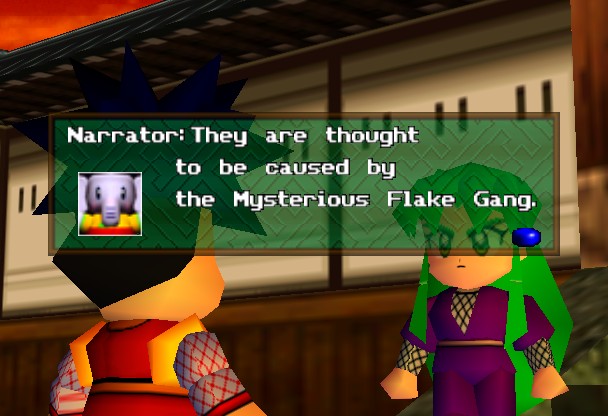

Mystical Ninja Starring Goemon [Nintendo 64] (Japan: 1997, North America: 1998)

The original Japanese version of this classic Konami game is filled with the word okama – often as a clear insult, but not always. This is because one of the main villains in the game is a flamboyant crossdresser with an exaggerated female speech pattern:

The beginning of the Japanese game includes multiple instances of the word okama. It seems that when possible, the English localizers tried to write around the word.

In this line, “okamas” was replaced with the word “members”:

And in this line, the whole sentence was changed to avoid the okama reference:

|  |

| "She had begun her own investigation by pursuing the mysterious okamas." | "They are thought to be caused by the Mysterious Flake Gang." |

When the word was less avoidable, okama was replaced with the English word “weirdo”:

|  |

| "Oh yeah! Where the heck did that okama jerk go!?" | "By the way, where did that weirdo go?!" |

|  |

| "You... OKAMA!" | "You... you WEIRDO!" |

Note that these examples are only from the beginning of the game. If I find any other noteworthy examples in the future, I’ll add them here.

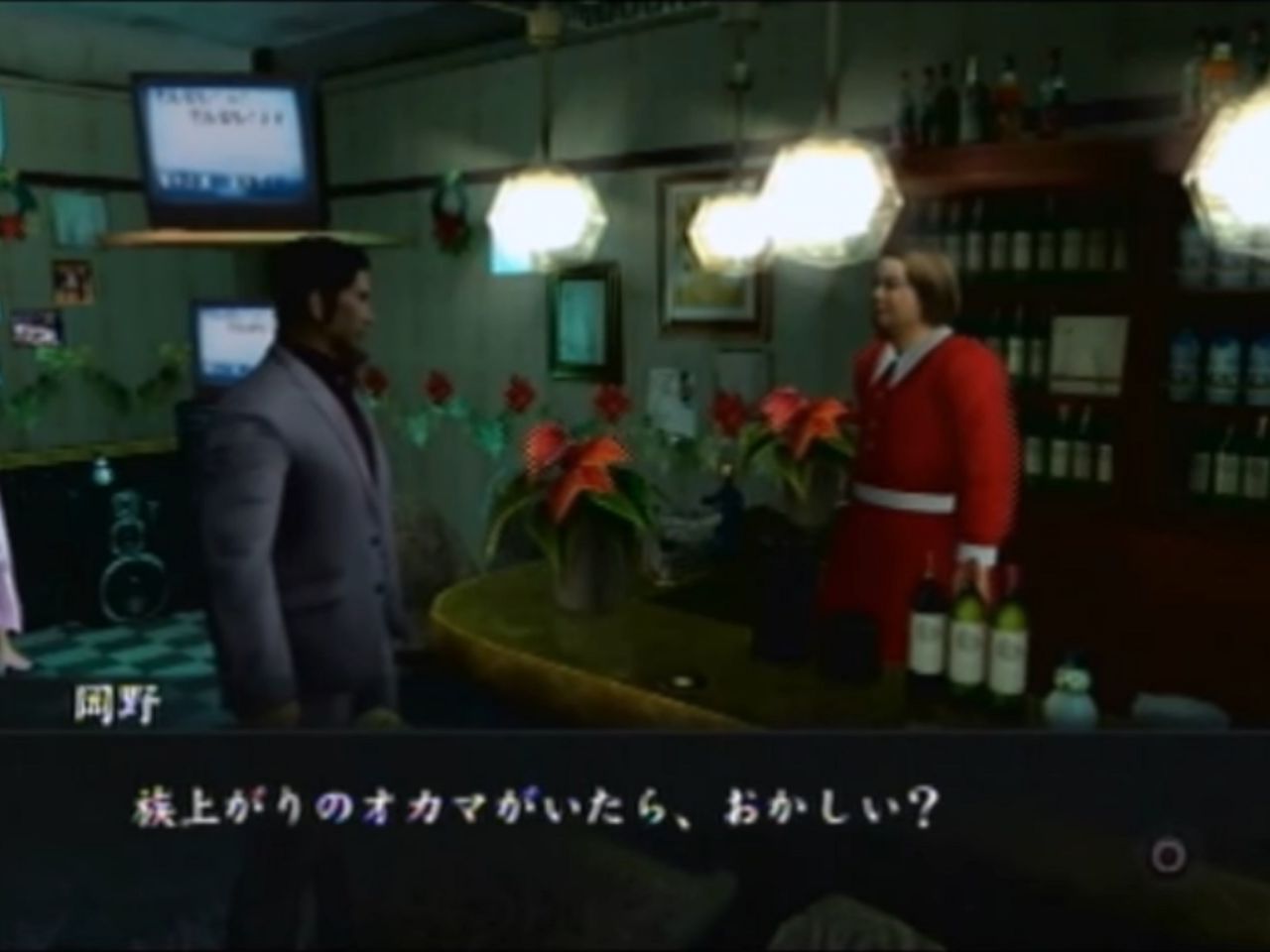

Yakuza Series (2005 – present)

Sega’s popular and long-running Yakuza series often features okama characters. And because most of the Yakuza games have received multiple translations and re-releases, we can actually see how treatment of the word okama has changed over the past 15 years.

Yakuza 2 [PlayStation 2] (Japan: 2006, Worldwide: 2008)

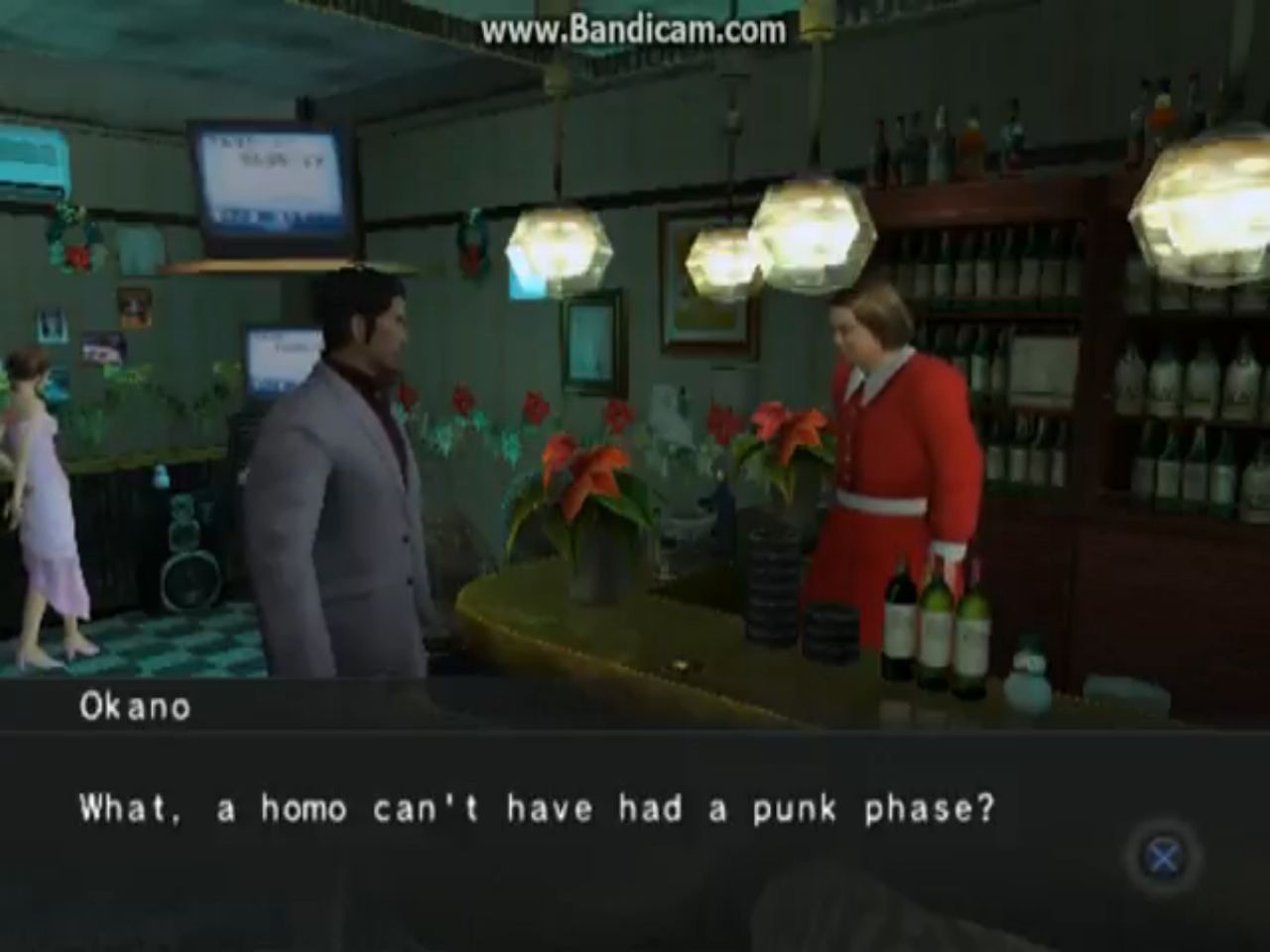

Yakuza 2 features an okama character named Ako/Okano who runs a bar. In the 2008 English translation, we can see that okama was translated as “homo”:

|  |

| "What, is it strange for there to be an okama who used to be a biker gang member?" | "What, a homo can't have had a punk phase?" |

Yakuza 2 received a complete Japanese remake years later, and was released in English in 2018. The game’s all-new translation also took a different approach to Japanese cultural terms. As a part of this new approach, the word okama was simply left in Japanese:

Yakuza 3 [PlayStation 3] (Japan: 2009, Worldwide: 2010)

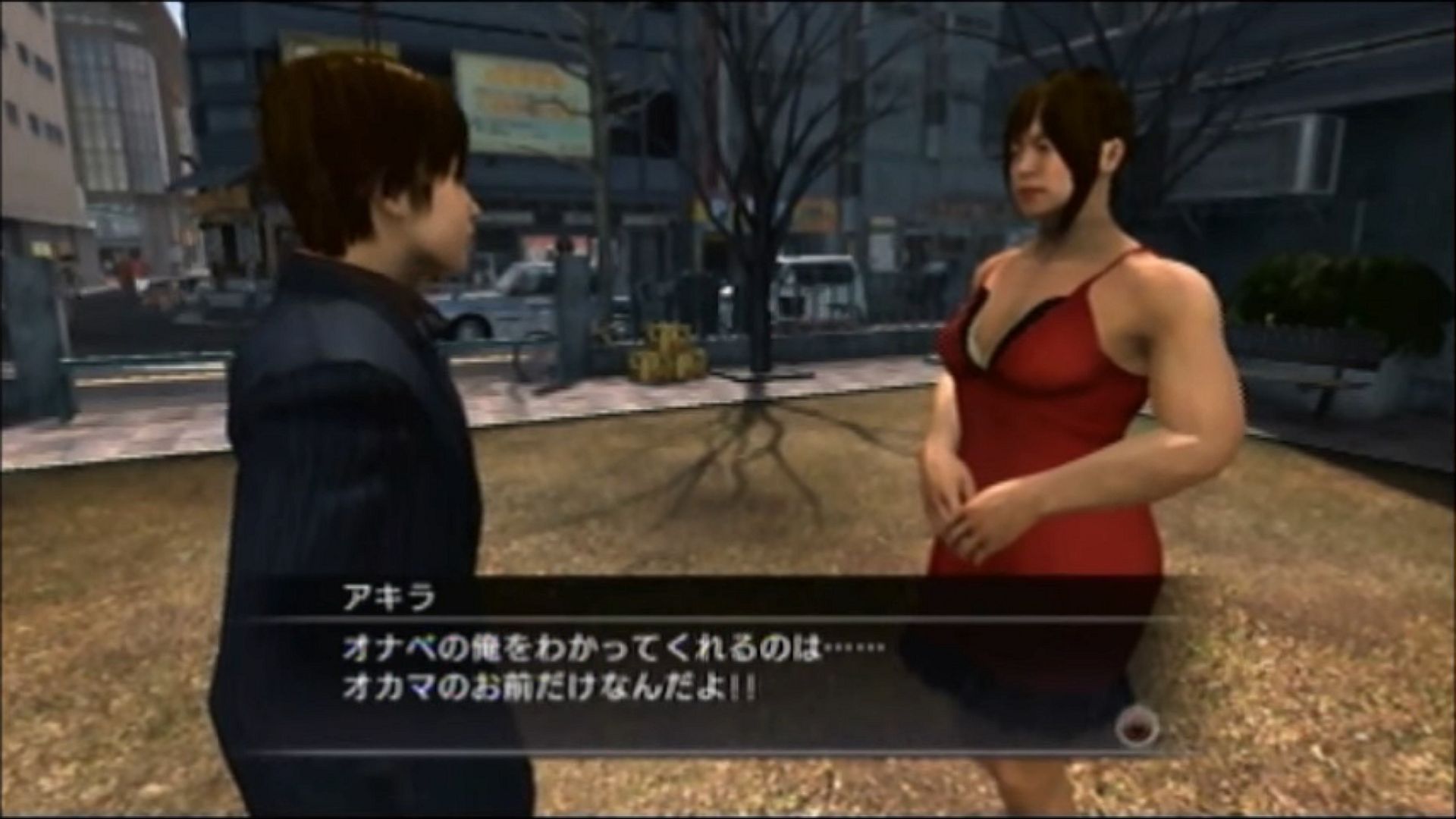

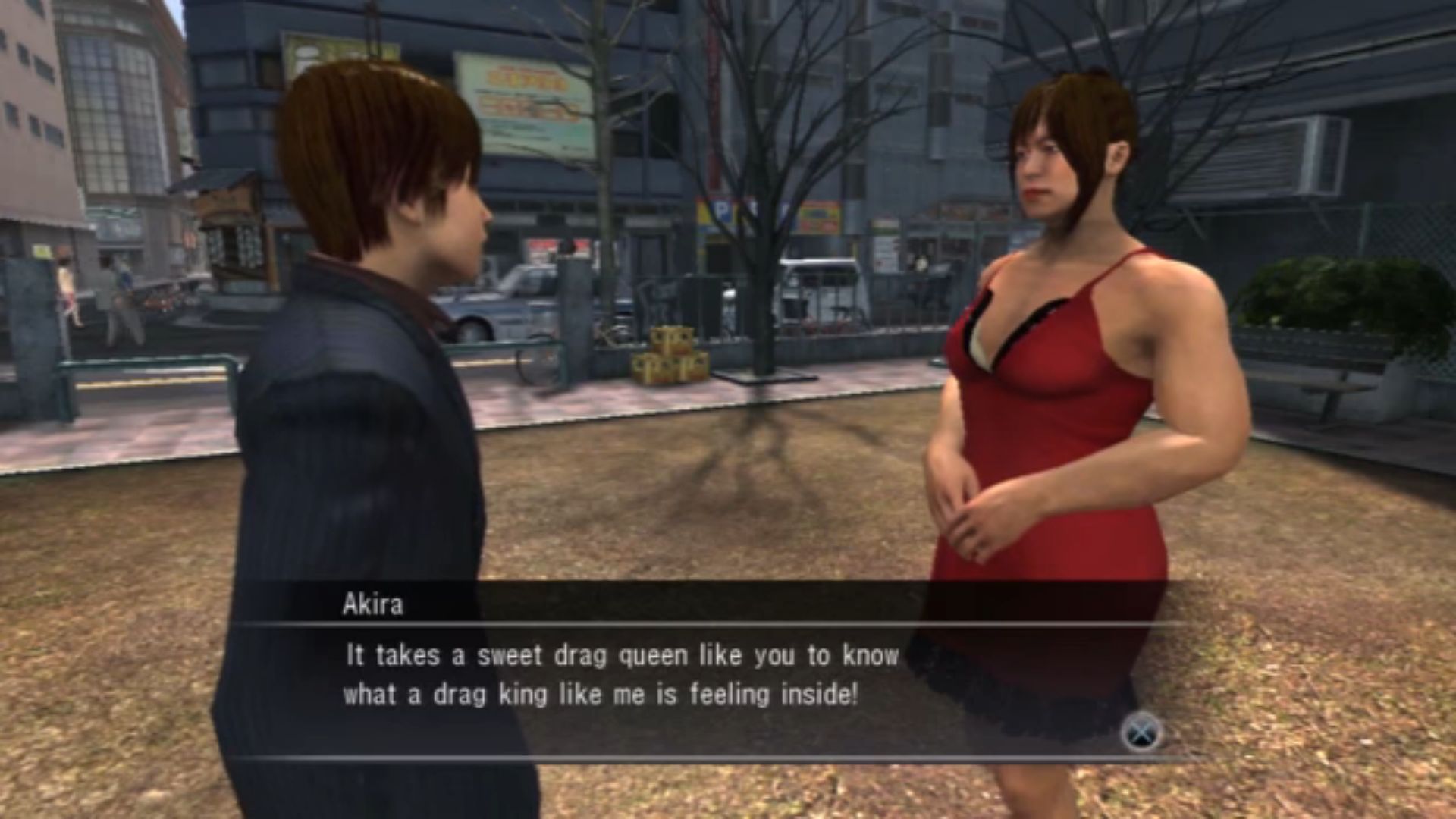

One side quest in Yakuza 3 involves an okama and an onabe. In the English release, these terms were translated as “drag queen” and “drag king”:

|  |

| "The only one who really understands me, an onabe, is you, an okama!" | "It takes a sweet drag queen like you to know what a drag king like me is feeling inside!" |

Almost a decade later, the game was re-released for the PlayStation 4. However, citing modern social sensibilities, the developers voluntarily removed okama-related side quests from the Japanese version. The same side quests were removed from the English re-release as well.

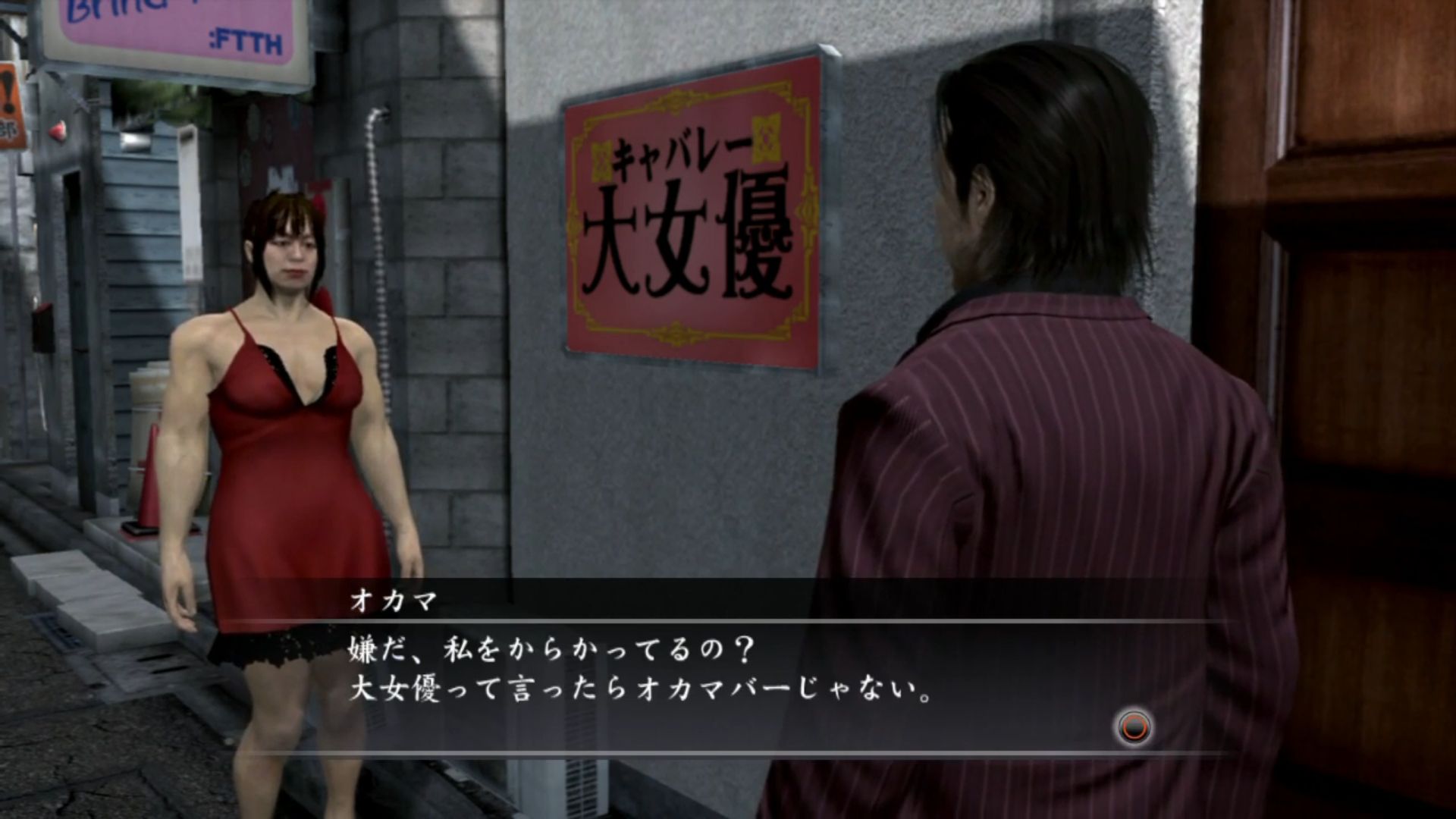

Yakuza 4 [PlayStation 3] (Japan: 2010, Worldwide: 2011)

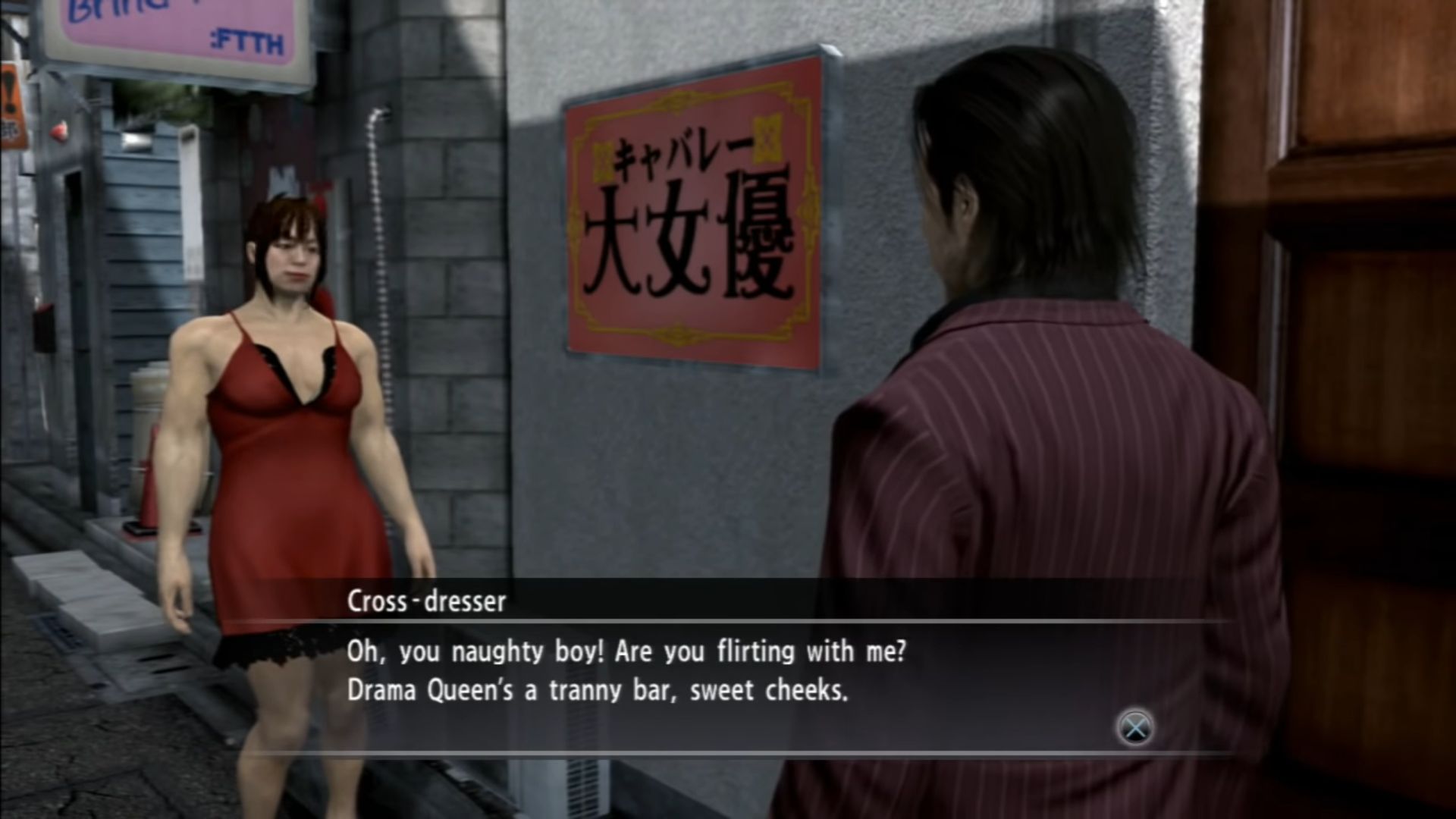

Yakuza 4 also features okama references. In one scene in the original translation, we can see that okama was translated both as “cross-dresser” and as “tranny”:

|  |

| Okama: "Oh, my. Are you playing with me? Daijoyū is so obviously an okama bar." | Cross-dresser: "Oh, you naughty boy! Are you flirting with me? Drama Queen's a tranny bar, sweet cheeks." |

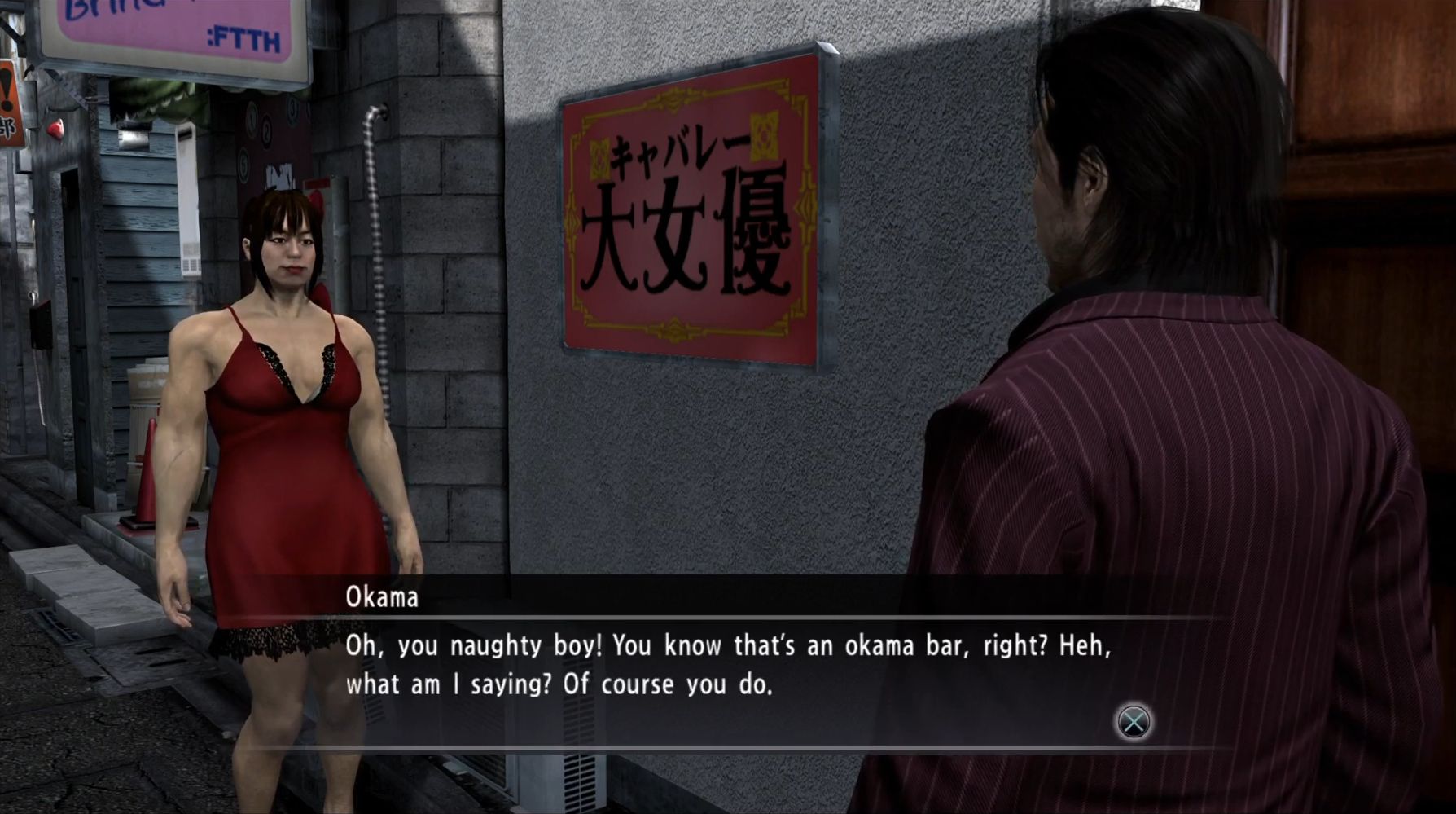

In line with the previous games’ re-translations, the English re-release of Yakuza 4 left the word okama in Japanese:

Interestingly, this 2019 English re-release also leaves “okama” unitalicized, unlike in the 2018 Yakuza 2 re-translation.

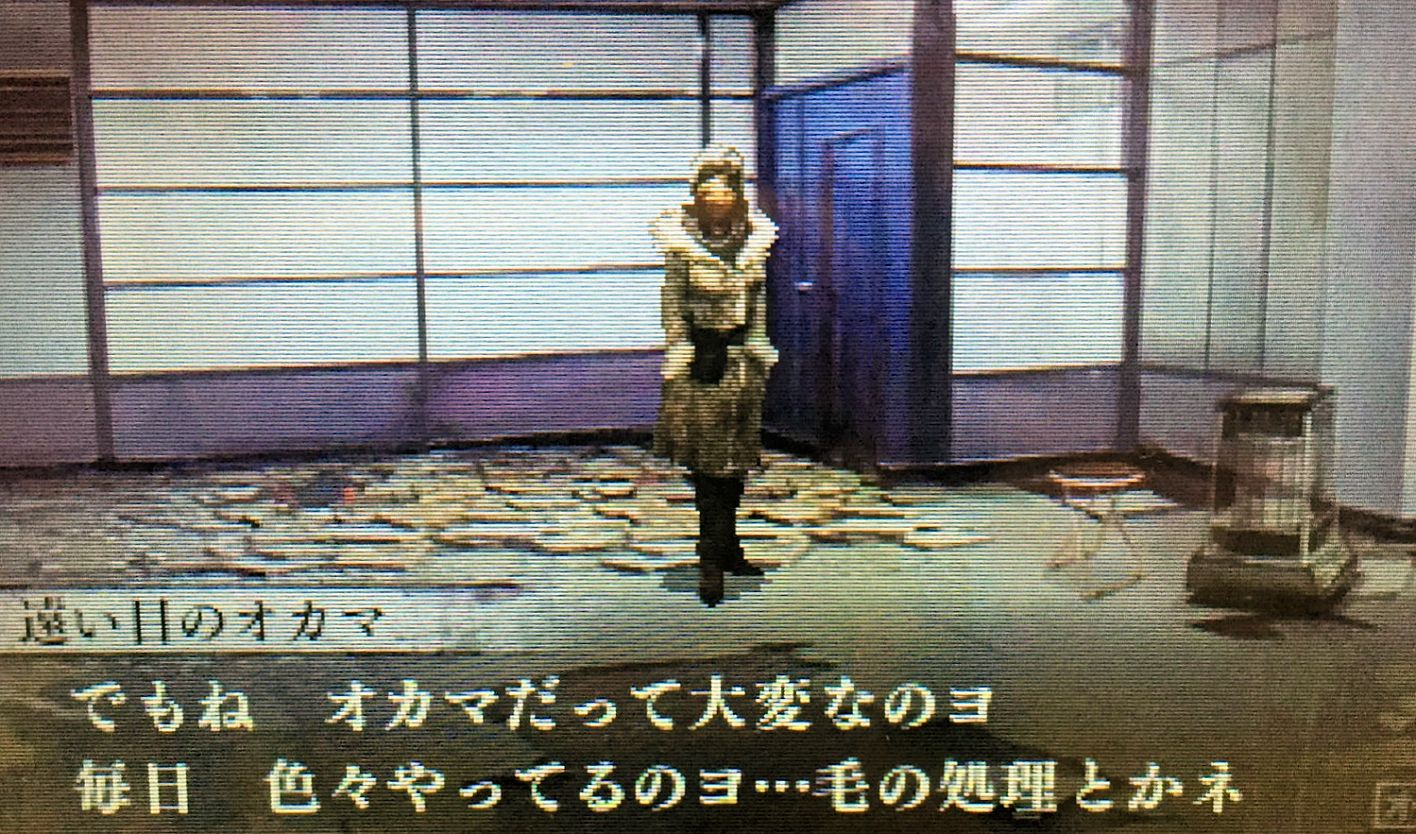

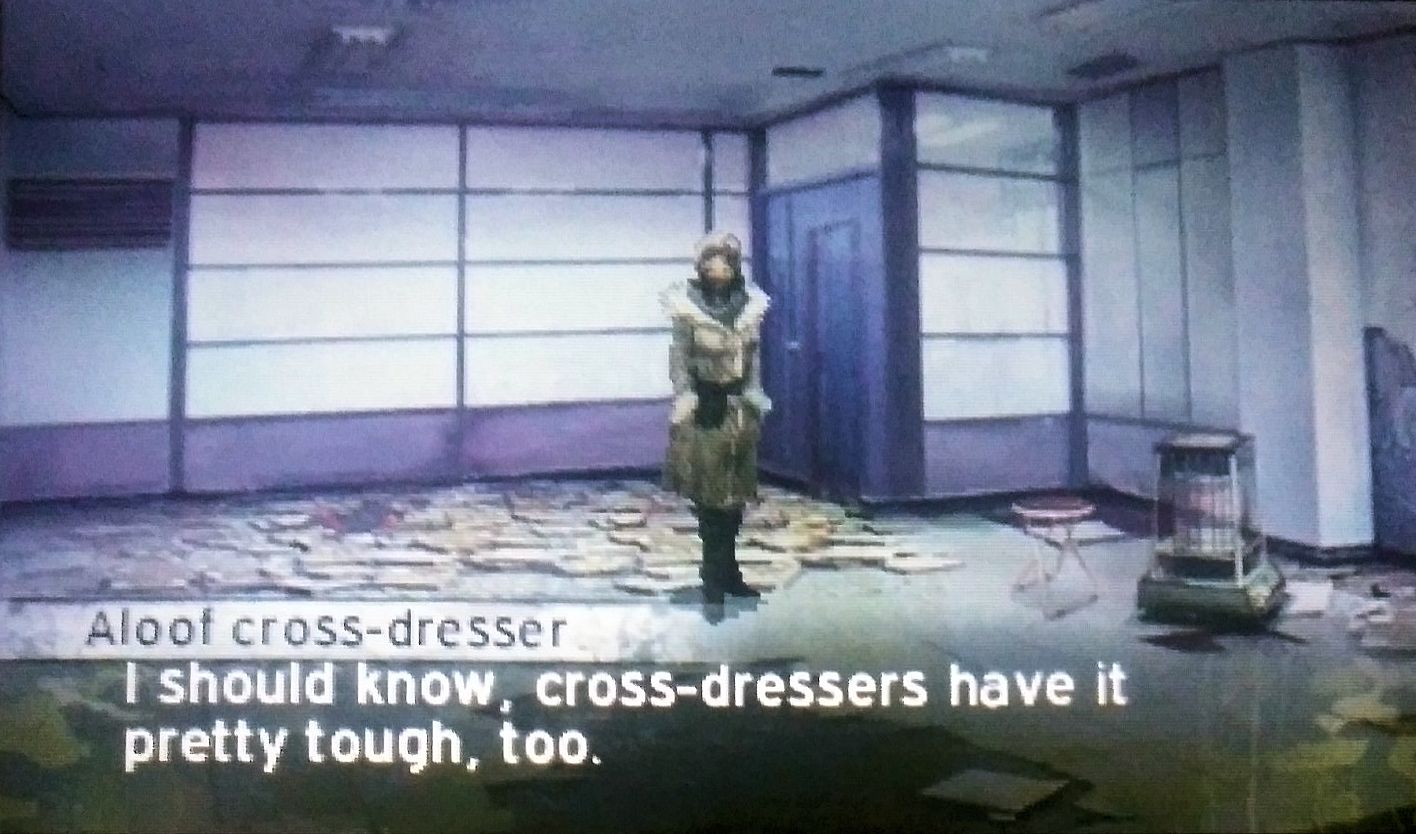

Shin Megami Tensei IV: Apocalypse [3DS] (2016)

In the Japanese version of this Atlus game, an NPC uses the word okama as a self-identifier. In the English release, we can see that okama was translated as “cross-dresser”:

|  |

| "But even okamas have it tough too, you know." | "I should know, cross-dressers have it pretty tough, too." |

Dragon Quest II and Dragon Quest XI [1987 – present]

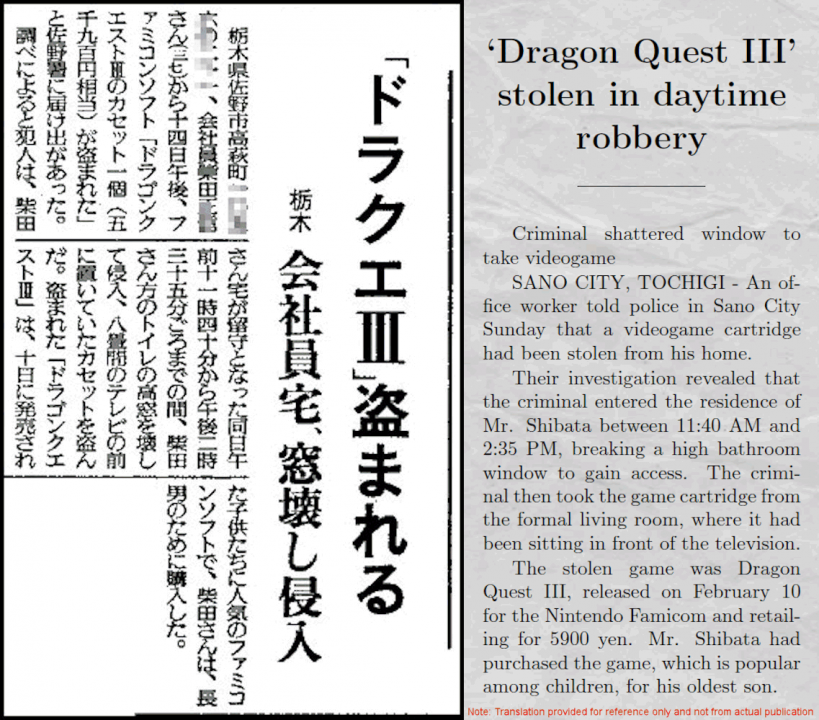

Dragon Quest fever sweeps Japan whenever Square Enix releases a new game in the series. It was especially wild in the 1980s and 1990s: fans camping in front of stores, TV reporters covering the situation live, wide-scale school absences, thieves stealing games from kids… the list goes on and on. The phenomenon even spawned an urban myth about the Japanese government making it illegal to release Dragon Quest games on weekdays.

In short, the Dragon Quest series was – and still is – enormous, mainstream, and beloved by millions of players in Japan.

I bring this up because Dragon Quest II includes an okama reference at a certain point in the script. What’s more, the game has received countless ports, re-releases, translations, and re-translations over the past 30+ years. This gives us a unique, historical look at how the word okama has changed in Japanese and in translation over time.

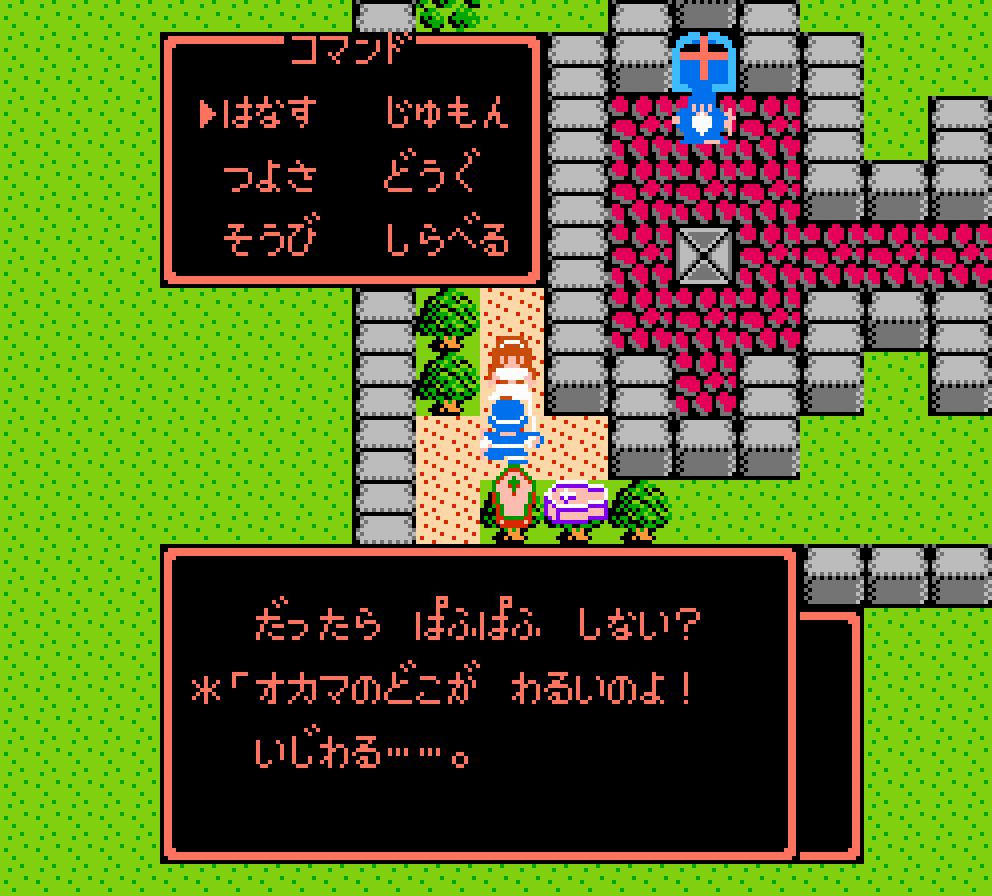

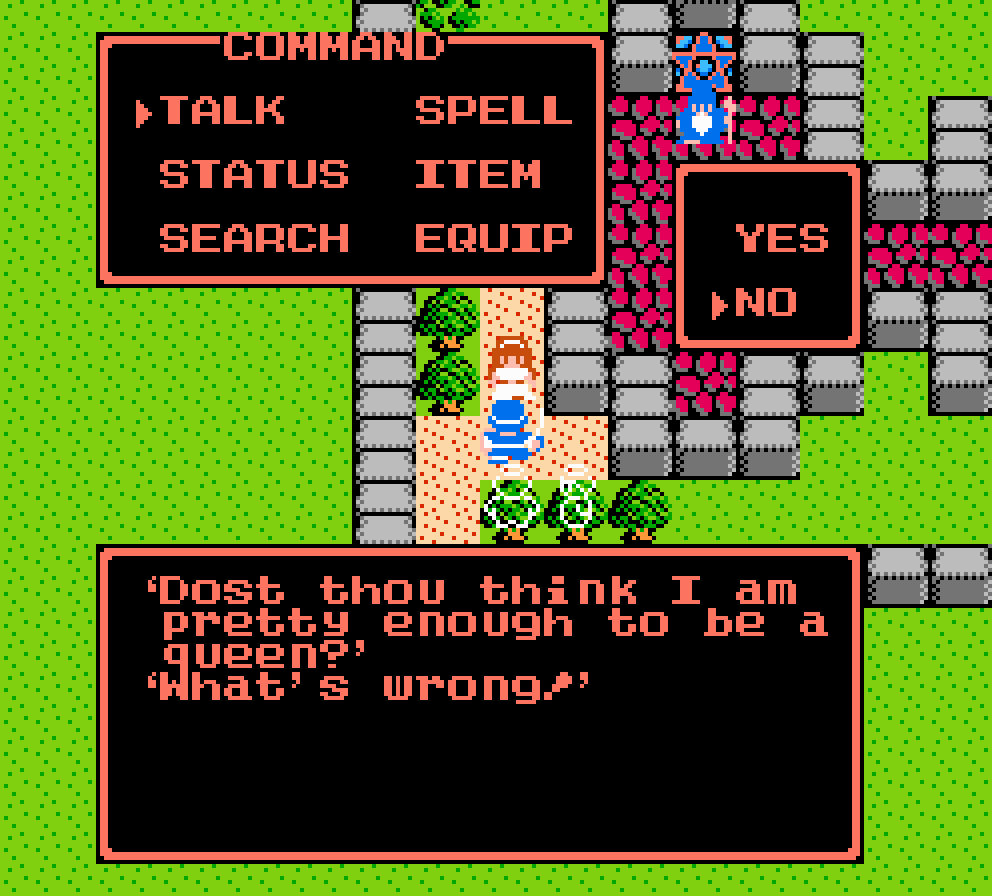

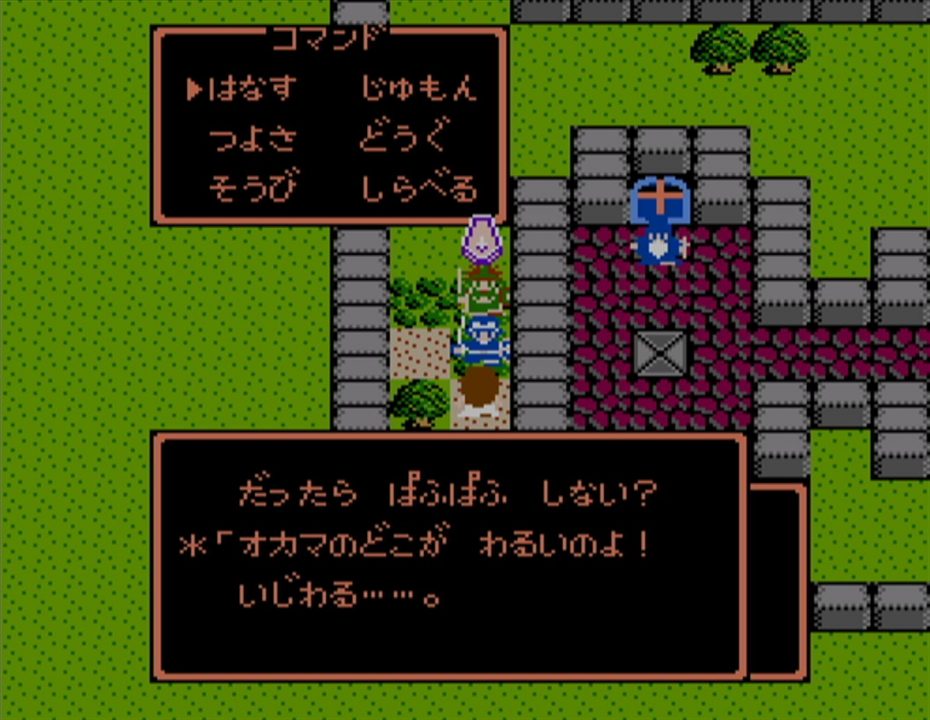

Dragon Quest II [Famicom] (Japan: 1987, North America: 1990)

The Dragon Quest series regularly refers to something called a “puff-puff”, which is implied to be an erotic massage that involves putting your head between a woman’s breasts. Puff-puff scenes are a running gag in the series, and they often end with surprise twists.

Many hours into Dragon Quest II, a character in a town offers to give you a puff-puff:

|  |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Hey, I’m cute, don’t you think? Then how about a puff-puff? | Dost though think I am pretty enough to be a queen? |

| If you answer “no” and your female companion is absent | |

| So what if I’m an okama?! You meanie… | What’s wrong! |

In the Japanese puff-puff scene, this character takes offense and reveals the surprise twist: they’re actually an okama. The English version of this scene, however, was rewritten to be more family-friendly.

Of course, the English word “queen” does have the slang definition of “a homosexual man, especially one regarded as ostentatiously effeminate”. As such, you could potentially argue that the original okama idea is technically still in the English translation, whether intended or not.

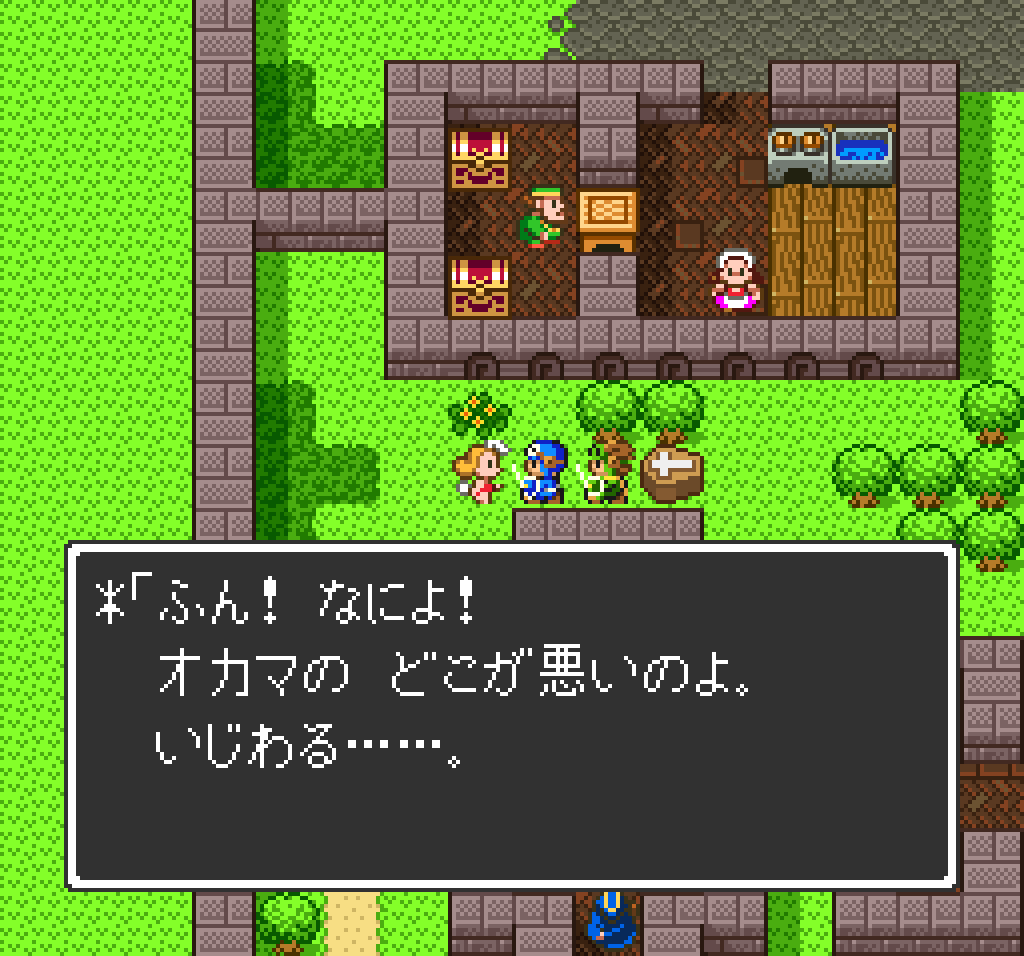

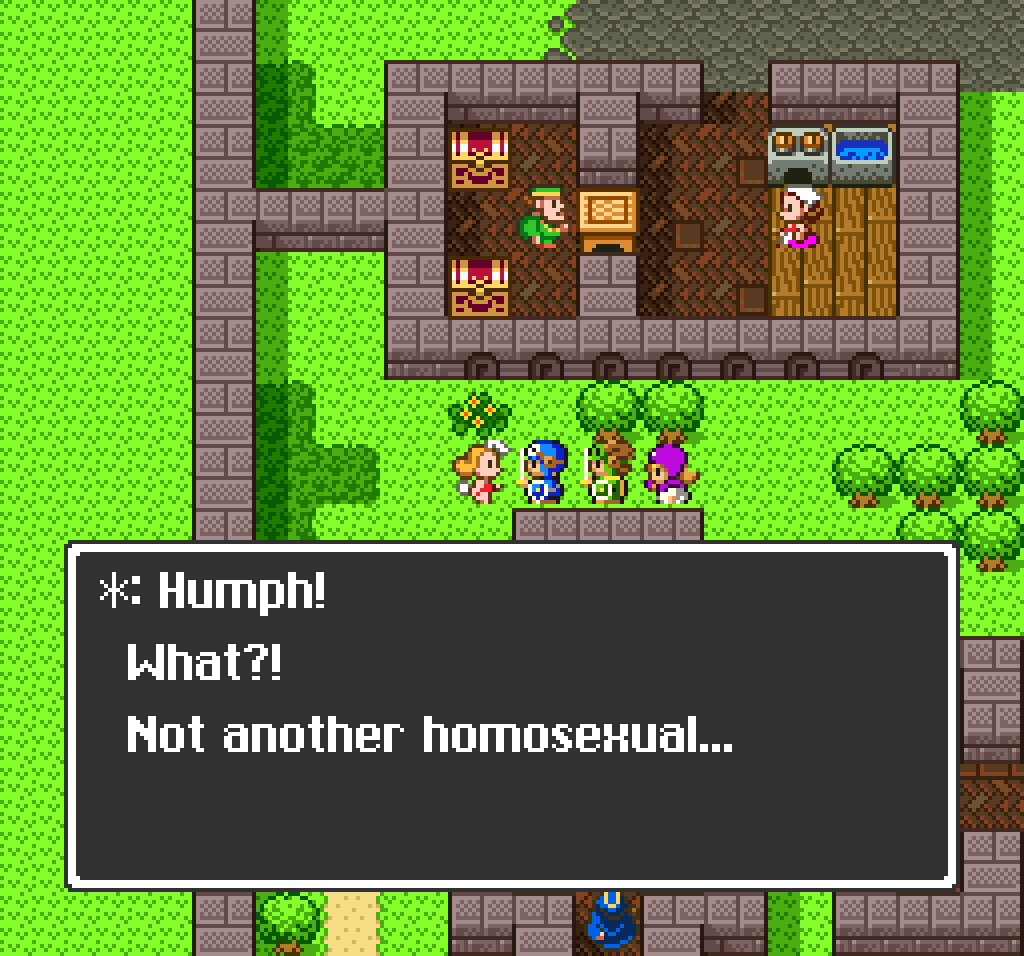

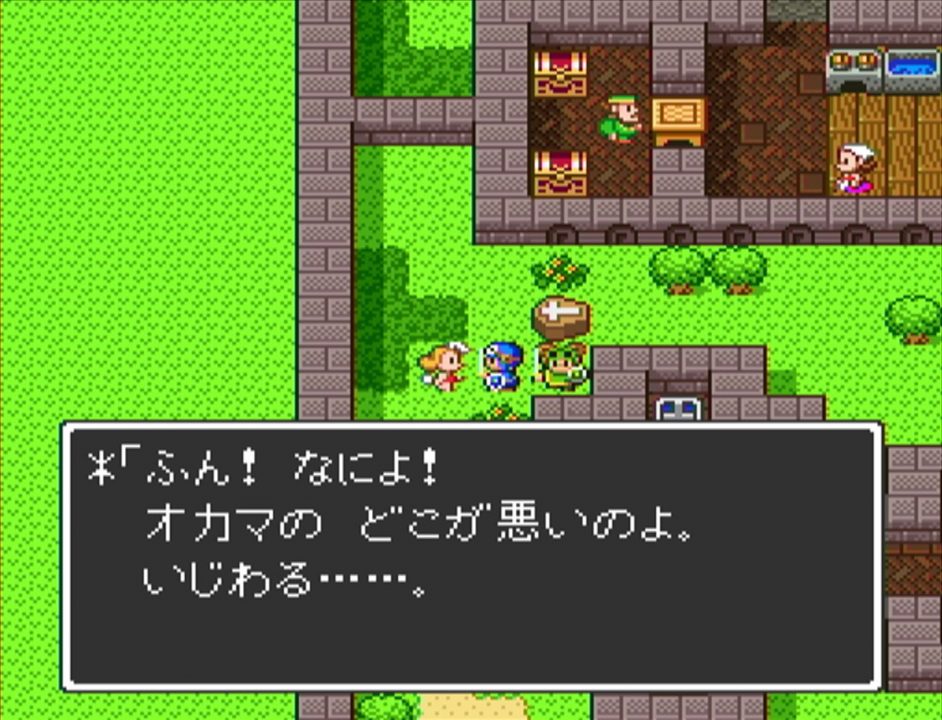

Dragon Quest I + II [Super Famicom] (Japan: 1993, English fan translation: 2002)

This new, upgraded version of Dragon Quest and Dragon Quest II featured improved graphics and sound, as well as text updates. Although this compilation was never released outside of Japan, fans created an unofficial English translation a decade later.

Here’s the same okama scene in this upgraded release:

|  |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | Fan Translation |

| Hey, I’m cute, don’t you think? Then how about a puff-puff? | Don’t you think I’m cute? Do you want a puff puff? |

| If you answer “no” and your female companion is absent | |

| Hmph! Gimme a break! So what if I’m an okama?! You meanie… | Humph! What?! Not another homosexual… |

In the Japanese version, we can see that the original okama reference was carried over into this new release. In fact, new text was even added to intensify the character’s displeasure.

In the fan translation, we can see that okama was translated as “homosexual”. The full line itself, though, was mistranslated. As a result, the character now appears to insult you, the player, by calling you a homosexual.

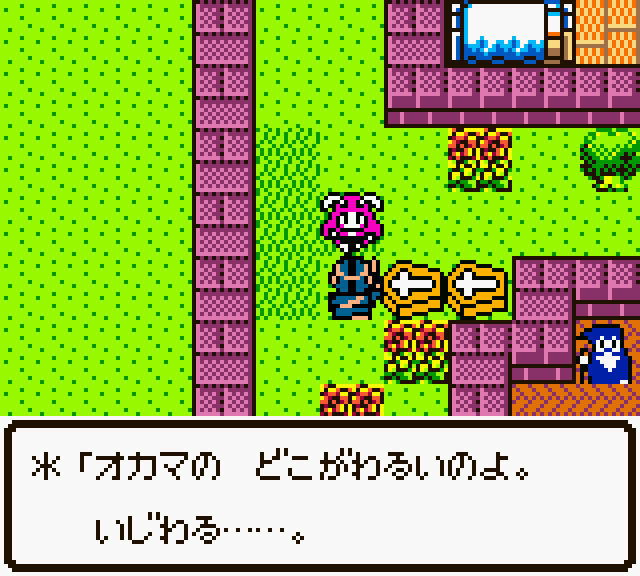

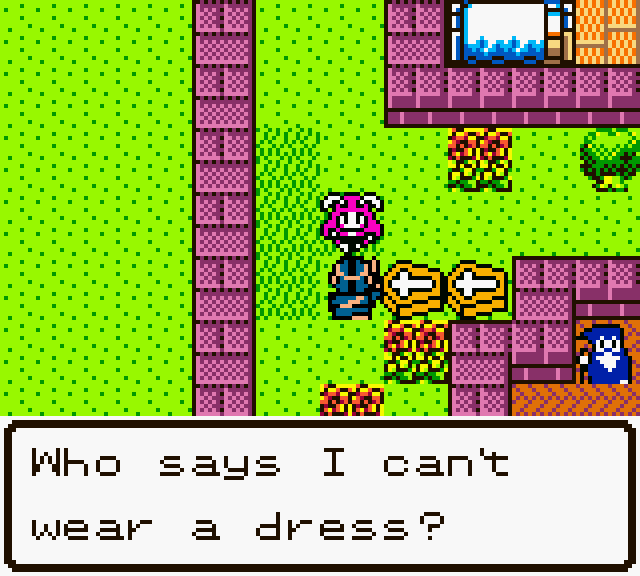

Dragon Quest I + II [Game Boy Color] (Japan: 1999, North America: 2000)

This portable version of Dragon Quest II was given a brand new official translation a decade after the original translation’s release. This time, the puff-puff massage reference wasn’t completely removed:

|  |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Hey, I’m cute, don’t you think? Then how about a puff-puff? | Do you think I look cute? Want a powder-puff massage? |

| If you answer “no” and your female companion is absent | |

| Hmph! Gimme a break! So what if I’m an okama?! You meanie… | Humph! So? Who says I can’t wear a dress? |

As we can see, despite the new translation, the okama reference was still dropped in this English release. Interestingly, the line does take on new meaning once you know the context of the original Japanese scene.

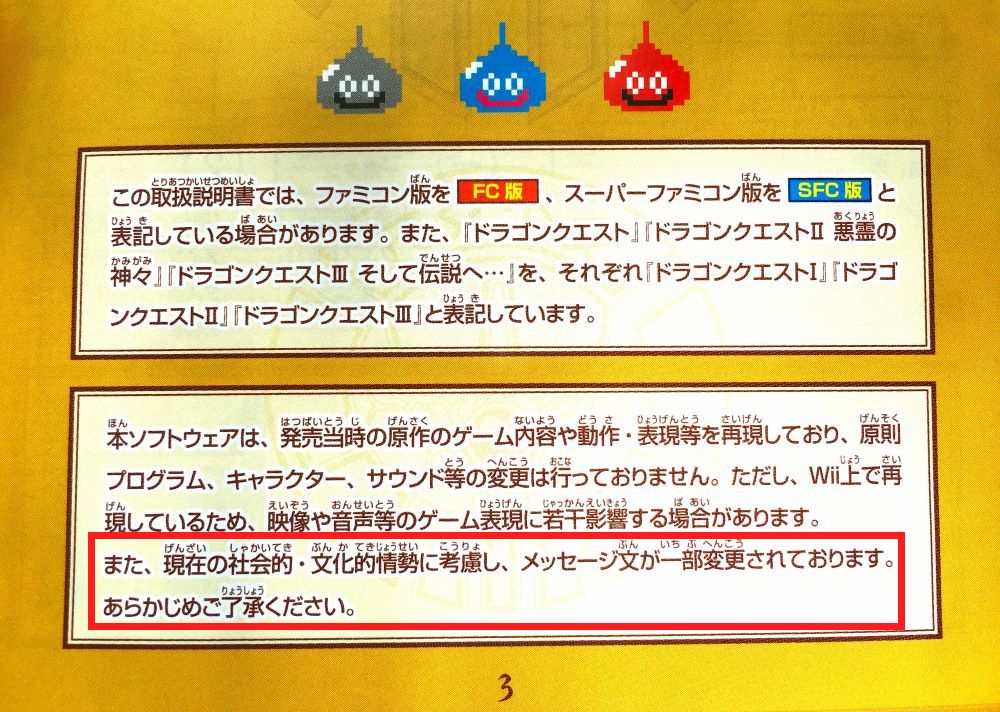

Dragon Quest 1+2+3 [Wii] (Japan: 2011)

This special Dragon Quest compilation was released exclusively in Japan to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the series. The compilation included two versions of Dragon Quest II: the original release from 1987 and the upgraded release from 1993.

Surprisingly, both the official website and the instruction manual included this small note:

The (games’) contents are mostly unchanged from their original releases, but in consideration of current social and cultural circumstances, portions of text have been modified.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much information about this topic online. What text could possibly have prompted these changes? Was it the okama reference in Dragon Quest II? Something else entirely?

To find out more, I bought my own copy of the anniversary compilation and played both versions of Dragon Quest II. After many hours, I discovered that the original okama references are still intact in the 2011 re-releases:

So if the developers altered text in this compilation for social and cultural reasons, then what text did they change? For now, it’s a mystery to me.

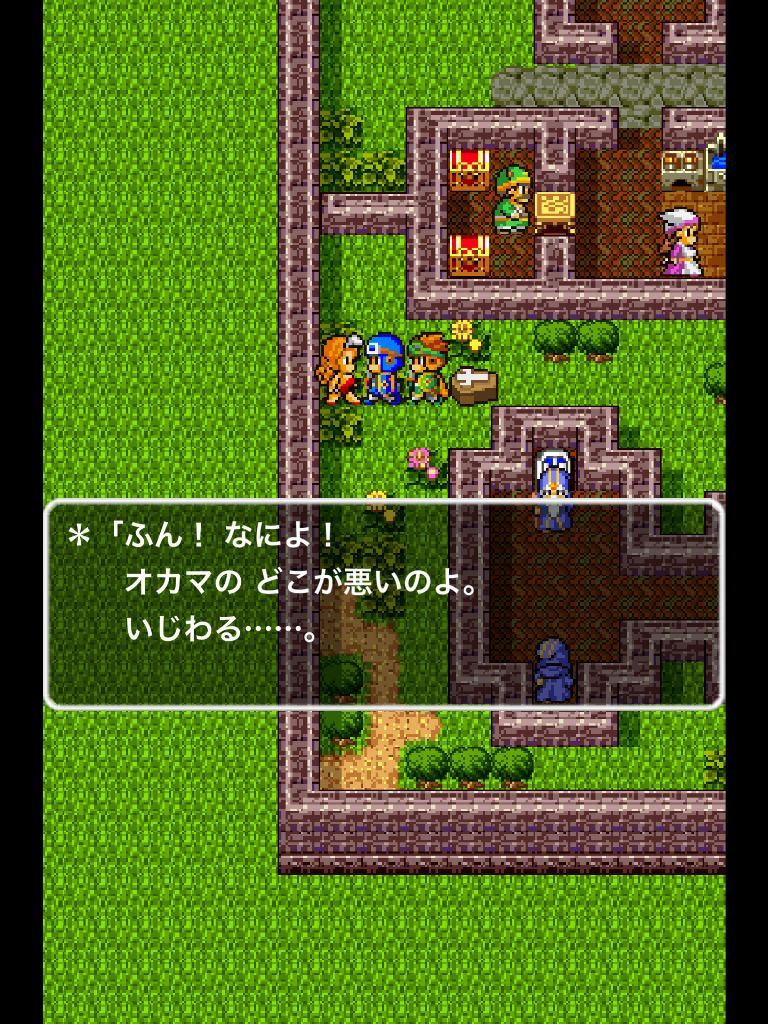

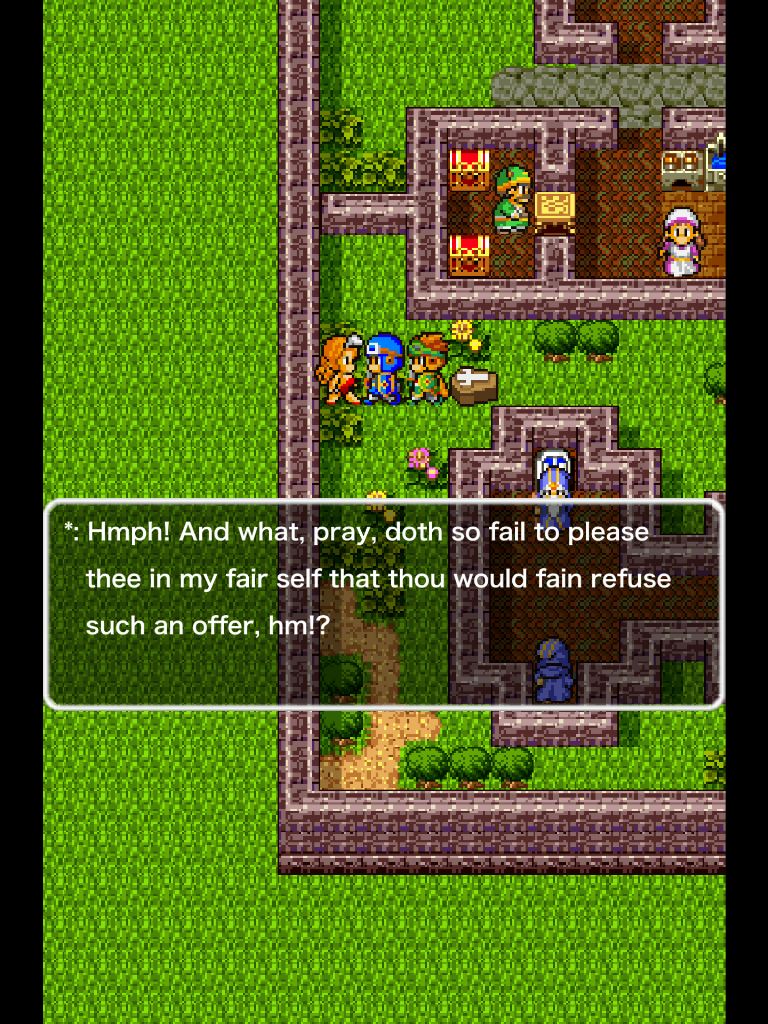

Dragon Quest II [Mobile] (Worldwide: 2014)

In 2005, a completely new remake of Dragon Quest II was released for Japanese cell phones. Unfortunately, the nature of this release makes it impossible for me to research today.

In 2014, a port of this cell phone remake was released for Japanese mobile devices. An English version was released several months later, and featured a brand new translation:

|  |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Hey, I’m cute, don’t you think? Then how about a puff-puff? | Do I please thee, good sirrah? Am I fair in thine eyes? Then mayhap thou wouldst accept from me a heartfelt puff-puff? |

| If you answer “no” and your female companion is absent | |

| Hmph! Gimme a break! So what if I’m an okama?! You meanie… | Hmph! And what, pray, doth so fail to please thee in my fair self that thou would fain refuse such an offer, hm!? |

As we can see, the Japanese mobile version still used the original okama line. The English translation followed the previous translations and again dropped the okama reference.

Dragon Quest XI [3DS, PS4] (Japan: July 29, 2017)

In a way, Dragon Quest XI is like one, big celebration of all the previous Dragon Quest games – everywhere you look, you’ll find cameos, references, homages, quotes, and more. You even get to travel back inside the previous games to experience them in new ways. Naturally, this specific puff-puff character makes an appearance too.

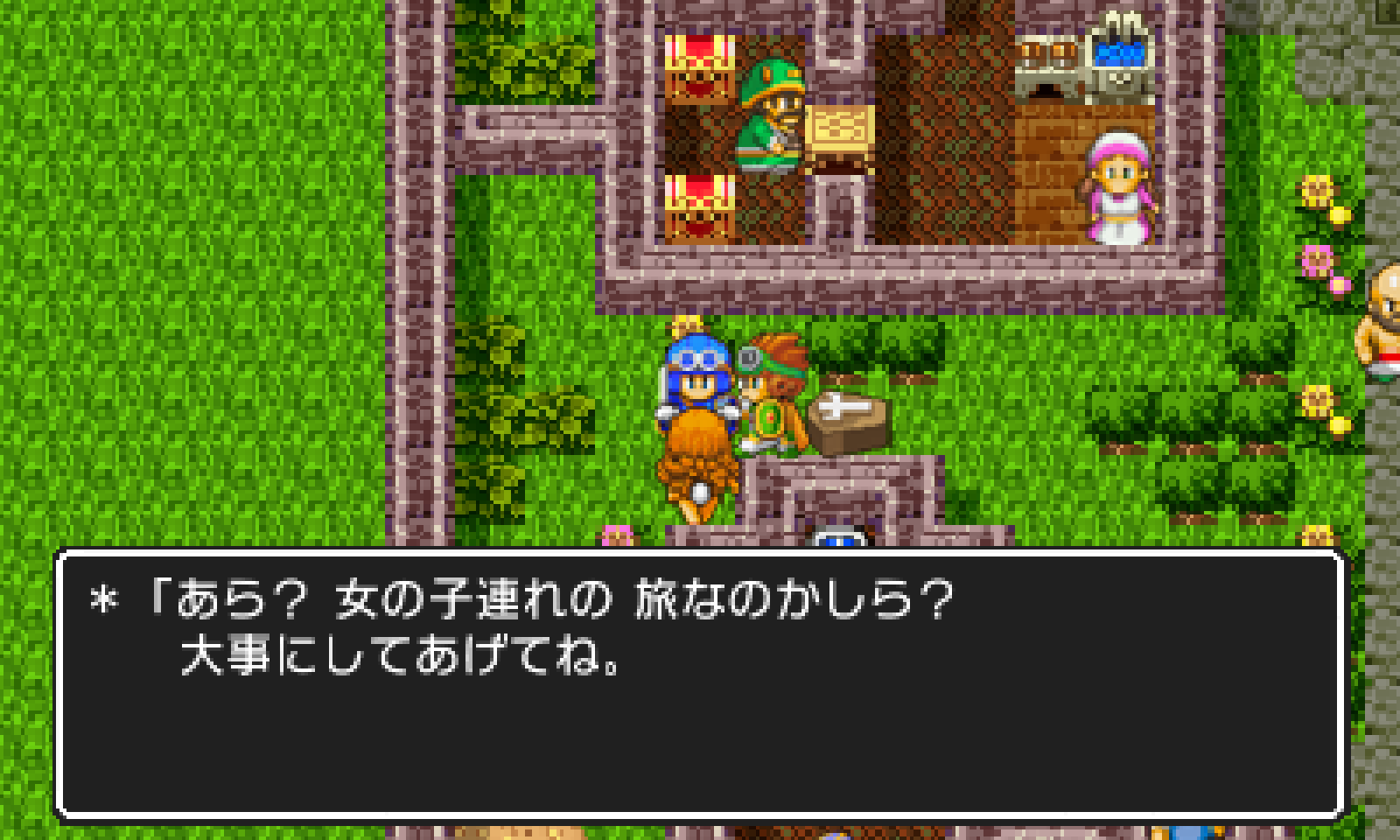

A few months before Dragon Quest XI debuted in Japan, a preview article included screenshots of this puff-puff character’s cameo. What’s more, one screenshot featured the exact same okama quote from Dragon Quest II:

(from April 11, 2017 preview article)

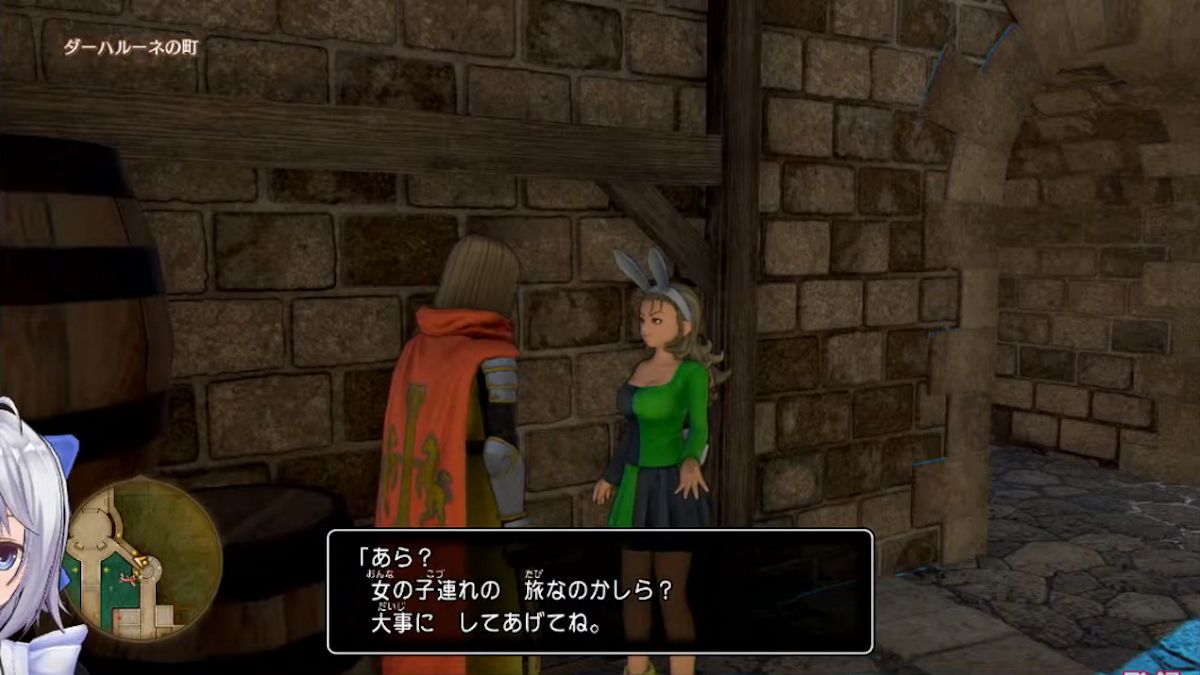

However, a YouTube video posted a week after Dragon Quest XI’s release shows that this okama quote was replaced with a completely different line:

(from August 4, 2017 YouTube video)

So did the okama quote get replaced before the game’s release, or did it get replaced in an update patch after the game’s release?

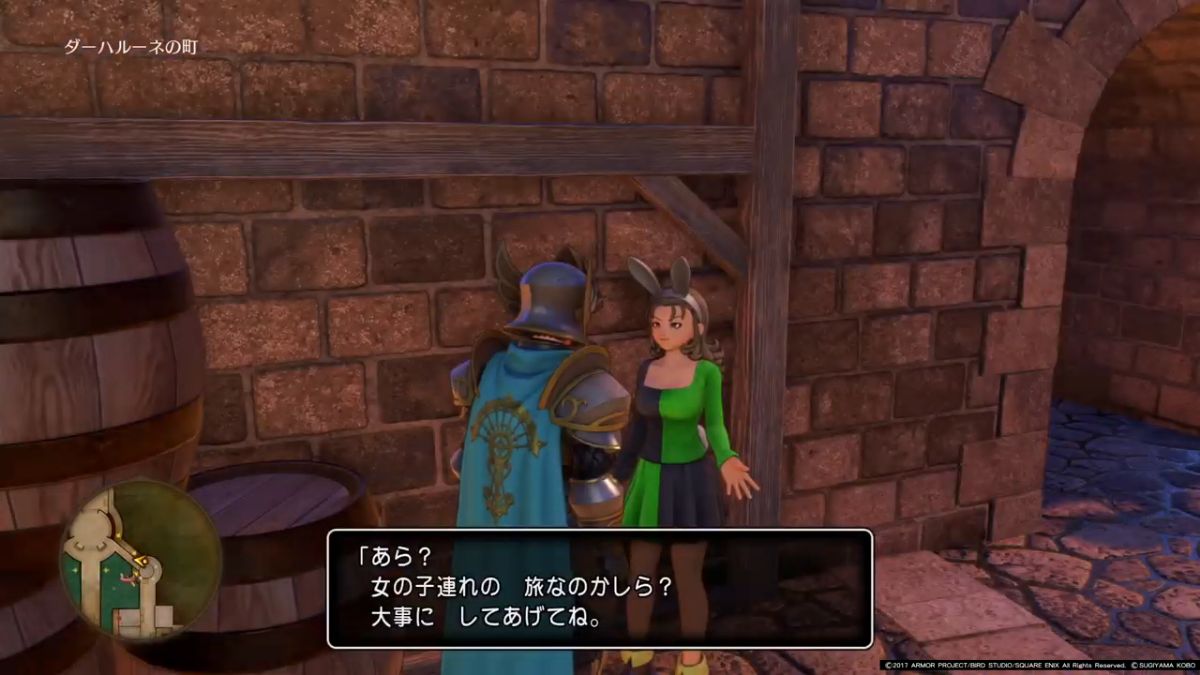

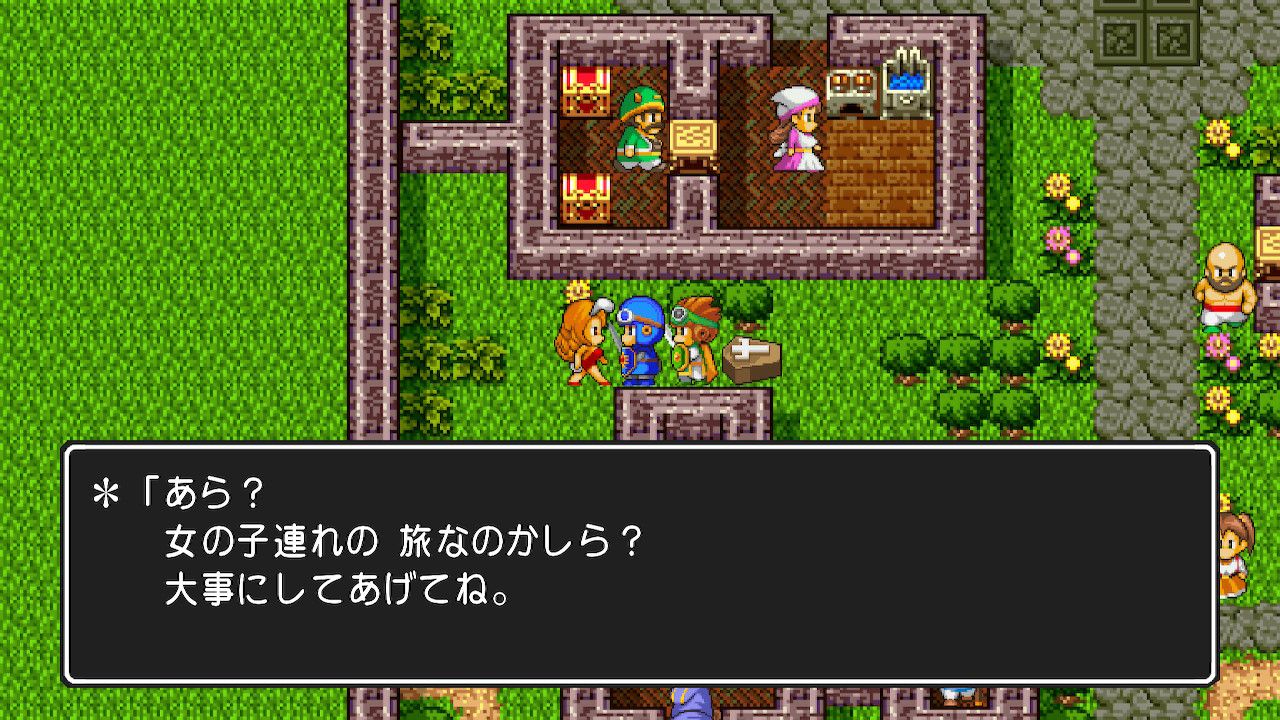

To find out, I bought a brand new, sealed, early purchase copy of Dragon Quest XI. After disabling updates, I loaded the game, jumped to the proper point in the game, and discovered that my copy of the game matched the YouTube video I had seen:

(from a brand new, sealed, early purchase copy)

In short, it seems that the original okama line was removed from Dragon Quest XI sometime between April 2017 and July 2017. My best guess is that someone important noticed the preview screenshot during those three months and requested the change.

It’s important to note here that the 3DS version and the PlayStation 4 version of Dragon Quest XI were released on the same day in Japan. The 3DS version was never released in English, but the PS4 version did receive an English release a year later, in 2018.

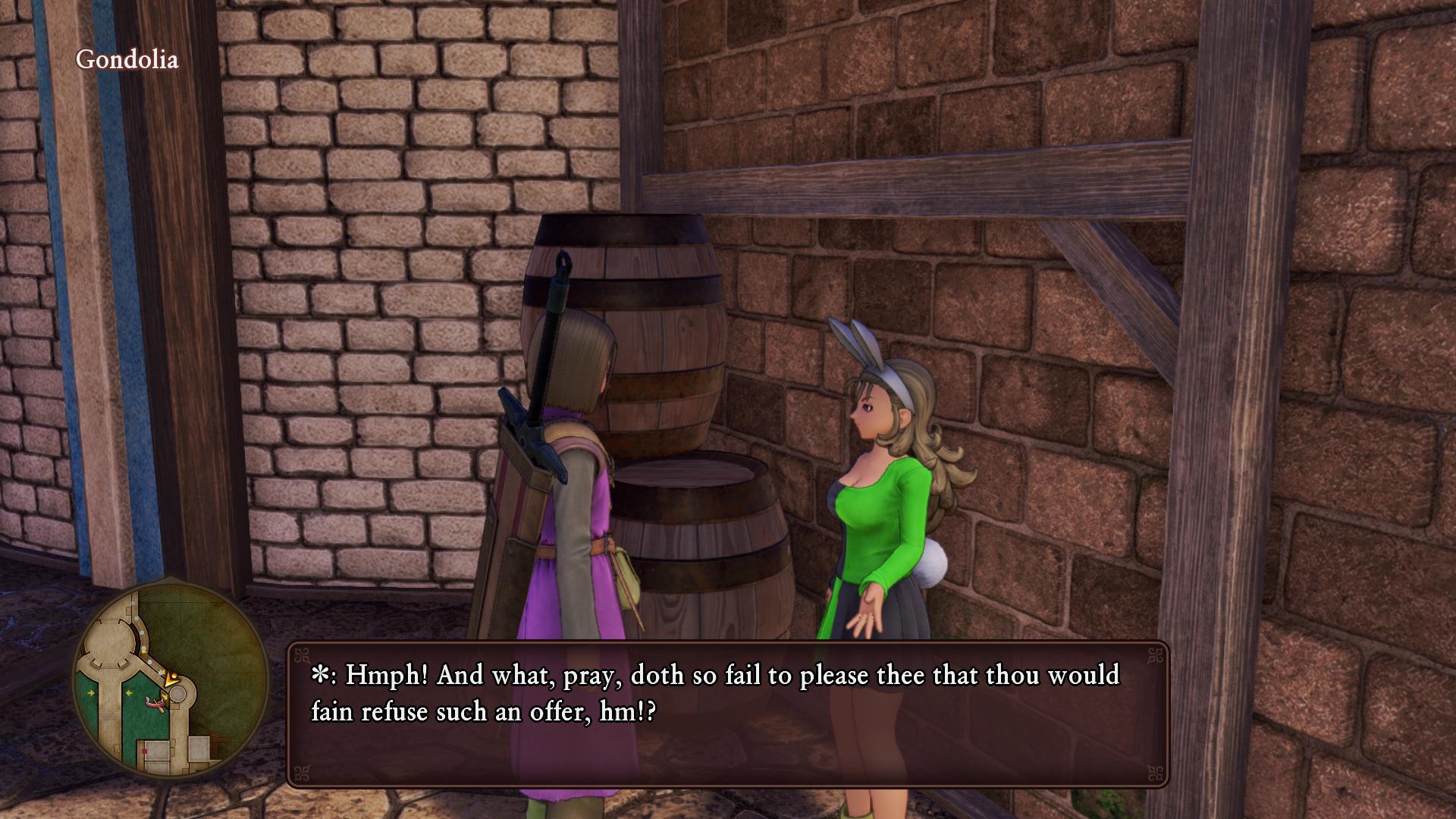

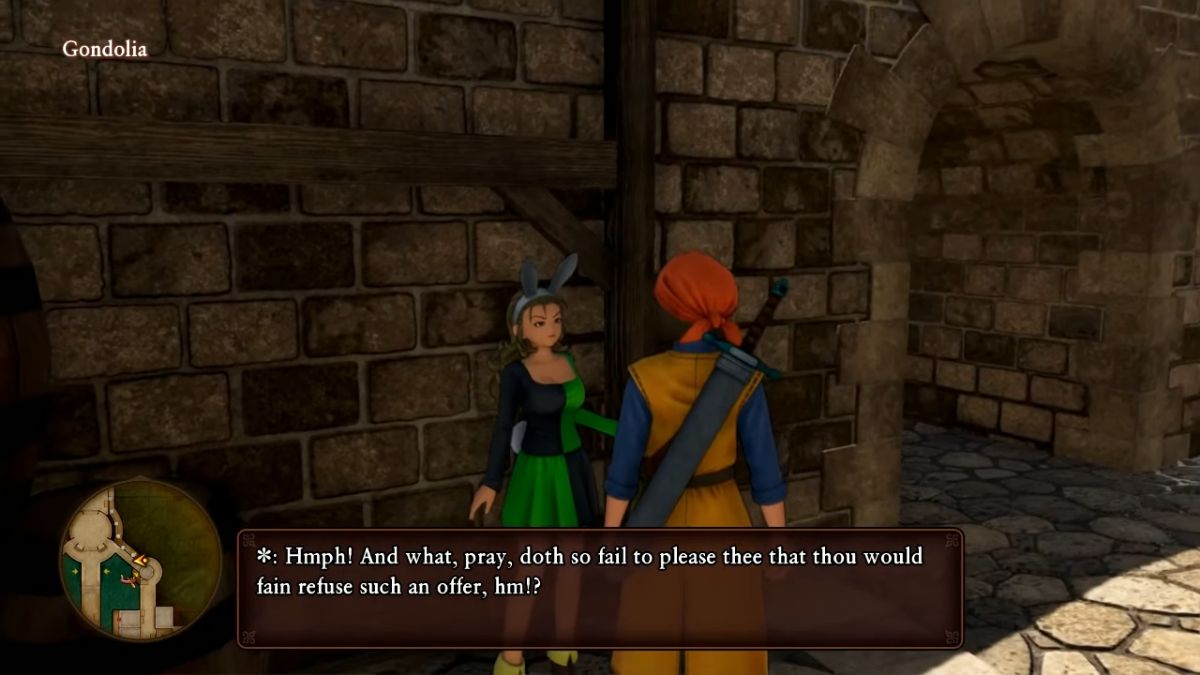

Interestingly, the line in the English PS4 release doesn’t match the updated Japanese line. Instead, the English line appears to be based on the 2014 mobile translation, although it’s not an exact quote:

|  |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Oh, are you traveling with a girl? Take good care of her then, okay? | Hmph! And what, pray, doth so fail to please thee that thou would fain refuse such an offer, hm!? |

Basically, it appears that the Japanese developers scrambled to remove the okama reference from Dragon Quest XI before its debut in 2017. Meanwhile, the English translators didn’t need to rush to change anything, because a replacement English line had already been devised years earlier.

Dragon Quest II [3DS] (Japan: August 10, 2017)

Two weeks after Dragon Quest XI’s debut, a port of Dragon Quest II was released for the 3DS. This version was based on the 2005 cell phone remake and was only released in Japan.

As we saw earlier, the mobile release retained the okama line. The 3DS version, however, uses the same replacement line found in Dragon Quest XI:

Incidentally, despite this text change in the 2017 3DS version, the 2014 mobile version still contains the okama reference even now, in 2020.

Also, it’s a minor detail, but the text formatting in this new Japanese line doesn’t match the formatting of the line in Dragon Quest XI. This suggests this wasn’t a simple copy-and-paste, set-it-and-forget-it content change.

Dragon Quest XI S [Switch] (Worldwide: September 27, 2019)

This updated version of Dragon Quest XI was released to a much wider audience than ever before. It featured changes to the original game, along with all new content.

For reference, here’s the puff-puff line in question:

|  |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Oh, are you traveling with a girl? Take good care of her then, okay? | Hmph! And what, pray, doth so fail to please thee that thou would fain refuse such an offer, hm!? |

As we can see, this puff-puff line is identical to the one from the original 2017/2018 releases of Dragon Quest XI. In other words, the okama reference is absent in both Japanese and in English.

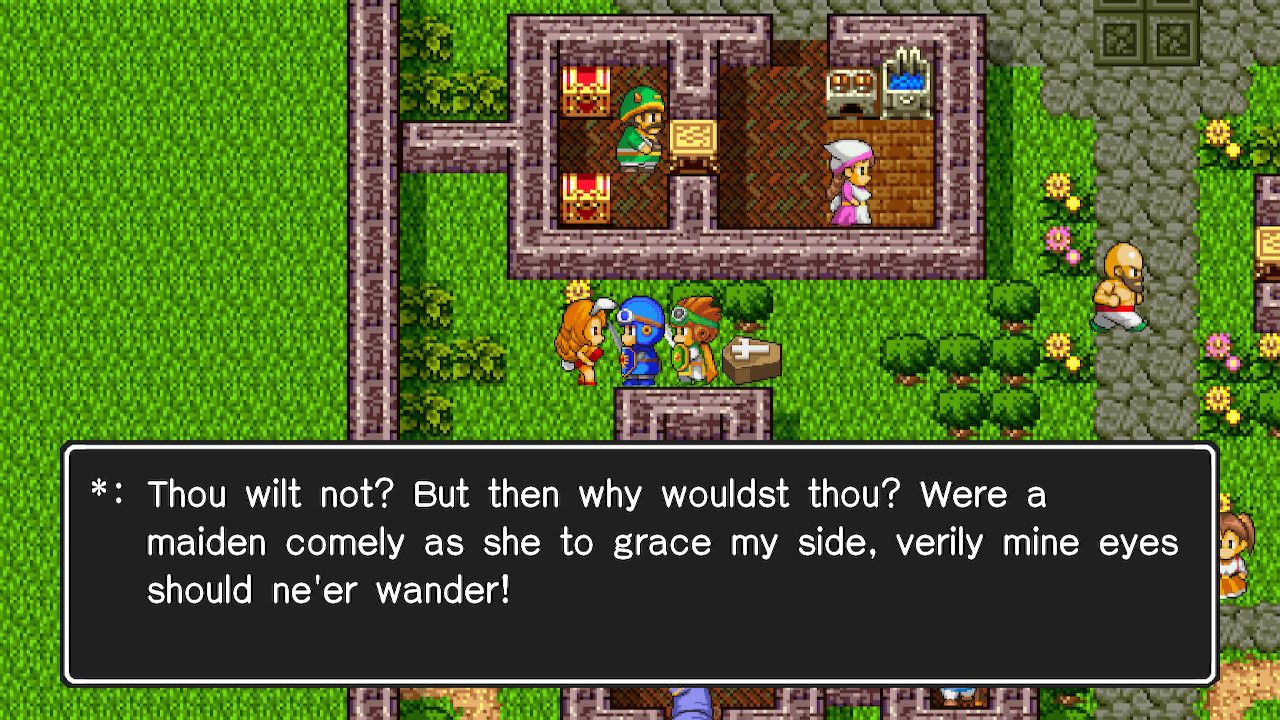

Dragon Quest II [Switch] (Worldwide: September 27, 2019)

This cell phone-based port of Dragon Quest II was released on the same day that Dragon Quest XI S was released. In the Japanese version, the okama line uses the same replacement line found in Dragon Quest XI:

|  |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Oh, are you traveling with a girl? Take good care of her then, okay? | Thou wilt not? But then why wouldst thou? Were a maiden comely as she to grace my side, verily mine eyes should ne’er wander! |

The text formatting in this Japanese line matches the formatting in Dragon Quest XI and not the previous Dragon Quest II release. This suggests the okama replacement line had to be manually re-entered again at some point. In other words, there’s probably a big note next to this line in the Japanese source code that says “BE SURE TO UPDATE THIS LINE IN FUTURE RELEASES”.

Surprisingly, this English line was also re-translated from scratch, even though the rest of the script is identical to the 2014 mobile translation. The new line doesn’t make much sense in context, though, given that it only appears when your female companion is absent or dead.

In total, this single okama-related line in Dragon Quest II has been translated at least six different ways over the years, and has been changed in Japanese at least twice.

Summary

We’ve looked at so many versions of Yakuza and Dragon Quest and whatnot that it’s all become a big blur by this point. What was the point of all this again?

There are two points, actually – to see how the word okama has been handled in video game translation over time, and how the word okama has changed in Japanese entertainment over time.

Okama in Translation Over Time

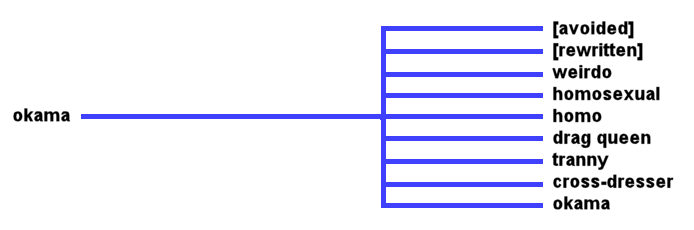

First, from the examples above, we’ve seen how okama has been translated in different ways across a variety of video games:

We’re working from a tiny sample size, of course, but it’s at least clear that game publishers initially tried to avoid or sidestep any okama references in translation. That practice continues to this day, but it’s also now more common to see okama references left intact and translated in proper context. We’re even starting to see the word okama left as an untranslated Japanese term when it fits the situation.

Okama in Japanese Entertainment Over Time

From the examples above, we’ve also seen that Japanese game publishers used the word okama without concern between the 1980s and 2010s. In the late 2010s, however, industry leaders began to consider okama a culturally insensitive word. Some publishers have even started to change and/or drop the use of the word okama and okama-related content. This new stance applies to new games and classic re-releases alike.

Final Thoughts

I first started studying Japanese in the 1990s, and I have a faint memory of a teacher mentioning the word okama and how it’s not a good word to use. But later on, during my studies in Japan, I kept seeing the word okama being used everywhere on television, in movies, in manga, and so on. This left me confused – was it a taboo word or not?

Over time, I gained a more natural, nuanced understanding of the word okama, but it was never a topic I formally learned about in Japanese classes or in translation courses. So I’m glad I was able to finally look into it in more detail and share what I learned here.

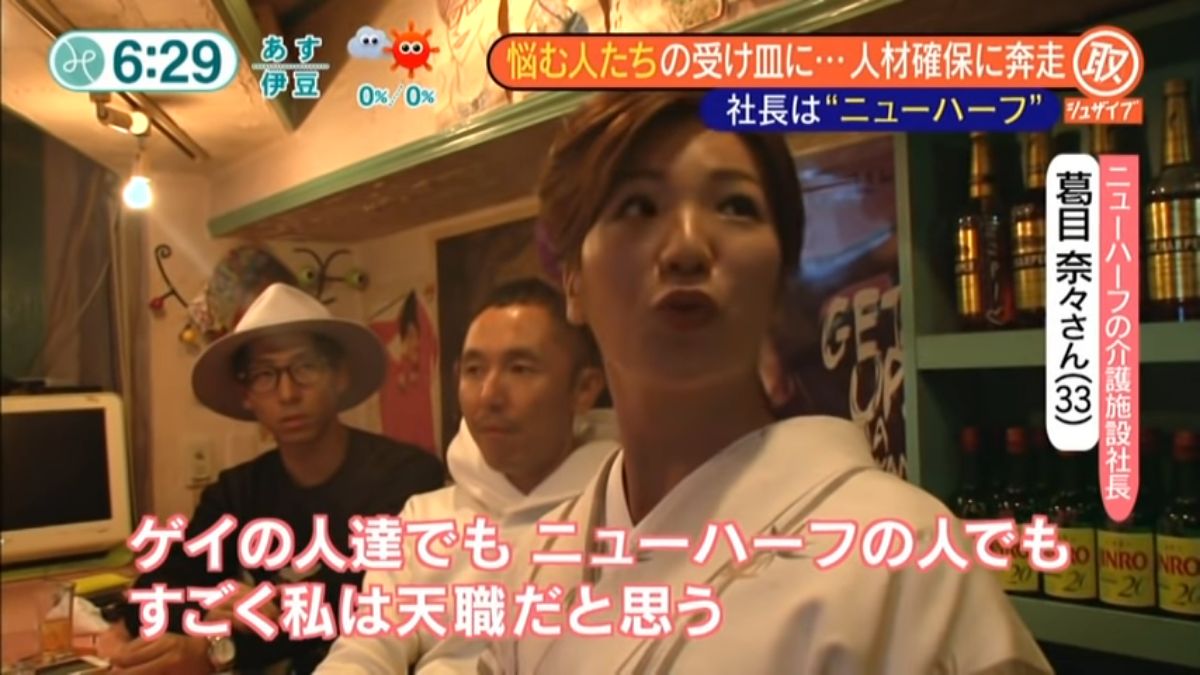

Anyway, we’ve looked at the word okama in detail in this article, but it’s only one piece of a larger picture. There are many other similar Japanese words that have their own unique histories, uses, connotations, and more. Some examples include:

- mister lady

- new half

- blue boy

- sister boy

- gei

- homo

- onabe

- onē

Many of these words come from the English language, yet have their own unique nuances in Japanese. It’d be neat to see how they’ve changed over time too, and to see how they’re still changing today. For example, I feel like onē has become a more considerate replacement of okama in recent years, but I bet something new will replace it in a decade or two. I wonder what it’ll be.

When I first started doing research for this article, I didn’t know what to expect. It’s interesting – we often hear about how language changes over time, but we rarely see how translation can change over time too. This has been a learning experience for me, and hopefully it’s been fun and informative for you too.

Also, if you know of any other examples of okama in Japanese entertainment translation, let me know!

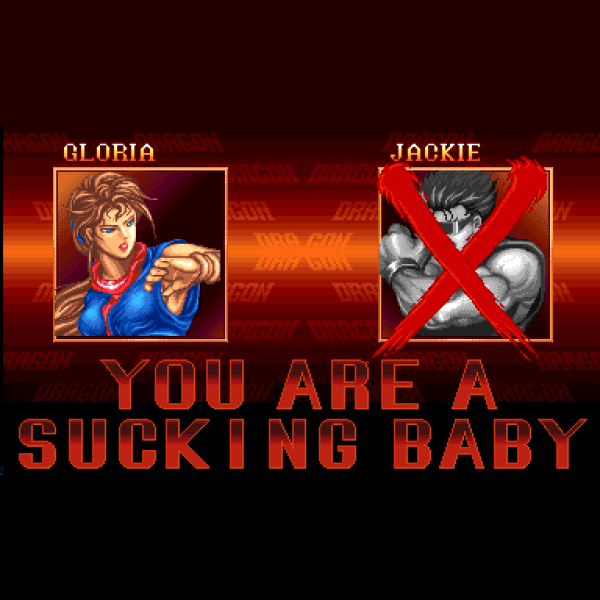

If you enjoyed this article, I've written a few other gender-related translation articles that you might like here. And if you're a fan of bad video game translations, you'll probably like this!

“So if the developers altered text in this compilation for social and cultural reasons, then what text did they change? For now, it’s a mystery to me.”

Well, now you’ve piqued my interest! I’ll have to look into this more when I have time. How difficult is it to dump an entire script from a Wii game?

My guess is that it’s the somewhat insensitive cultural stereotypes in parts of III.

I actually learned earlier today that Yakuza 4’s remaster had voice lines flat-out re-recorded to sidestep using the word in the Japanese version. No idea how far the rest of that version’s script goes, though.

https://twitter.com/kazu_watch/status/1127822123580264450?s=19

IIRC, in Dragon Quest 3 there’s a little boy in the second town whose dialogue changes if you’re playing as a female. In the original NES version, he reacts negatively on finding out the hero is a woman, while in later versions he just asks you to beat up the monsters.

I know the GBC translation has this kid acting surprised in an impressed sort of way to learn that the protagonist is a girl, although I’m not sure how translated iterations of this line match up with its iterations over the years in Japanese.

This reminds me of the time “newhalf” got translated as the t-word in a recent Goemon fan-translation, and everyone got triggered to hell and back and harassed the translator over it. Nevermind that it was the original line that was offensive in the first place, and the translator was just doing their damned job.

What do you think the kairos of this article is…?

I think this also shows that they weren’t exactly in the wrong for that reaction, also–it literally shows how translations of a similar term have changed to be more respectful in recent years.

Mm, I feel like “newhalf” is a bit kinder and more nuanced than the outright slur used in the translation

Well, you know, outrage culture doesn’t care about context.

I saw this controversy and this is the exact opposite of what happened. The fan translator lost their shit upon recieving reasonable criticism for their insensitive translation choice. The critic HardcoreGaming101 even went out of their way to suggest reasonable alternatives based on the source text.

The article we are commenting on shows that language marches on, slurs aren’t acceptable, and fan translators can be wrong.

That’s a complete and utter lie. Kurt from Hardcore Gaming 101 was the one that spearheaded all the harassment and dogpiling against the translator, using his follower base to spread hate and lies. Some people were offering alternatives but the majority of the feedback was hateful, which was too much for him. He went offline because it was just so devastating to receive so much hatred in such a short amount of time for something he didn’t even know was wrong.

If a slur isn’t acceptable, then the sensible thing is to work calmly with the person, not go instantly for their head.

Even though “tranny” was an unfortunate choice given the scene’s context (just a newhalf worrying about coming out to her boyfriend), the bulk of the controversy was definitively sparkled by HG101 hastily branding the guy a transphobic on the basis of a “Resetera is cancer” remark on his bio and the people on his follow list. And also SnesCentral arguing that hobbyist translators are obligated to censor the works they translate, even in such cases as the obviously non-nazi manjis featured in Goemon 3.

The manjis are everywhere in the game. It’s part of the title design and title name. One level has a statue of the villain posing his arms and legs in the position. The blocks you can grab onto with the pipe have the symbol, though they changed them to star blocks in the N64 games. One of the last bosses has the symbol in the background. The last boss gets defeated while in the pose as well. And if you get 100% clear in the game, it puts a manji icon on your save. It’d be a crazy amount of work to take it out.

And there’s a distinction between the translator (Tom) and the hacker/programmer. Tom would never do anything out of hate, he was using a term he heard people use unchallenged from 10 years ago. Even in this very article, Yakuza 4 used it in 2011, and it was changed in the re-release in 2019. What’s important is intent. He had no problem changing it, and it even did get changed, though too late for some.

Removing manjis and revising the “tranny” translation are not the same situation at all. Translating the word newhalf is open to interpretation. It is not censorship to translate it using a different word. Criticism of a translation choice is not the same as calling for manjis to be removed.

Wasn’t the reason there are so many manjis in the first place a reaction to how they were removed in official translations of earlier games?

Plus it wasn’t just a demand to use a different word. Even after the patch was forcibly censored ResetEra was still complaining the rest of the sentence wasn’t changed.

What’s wrong with the rest of the sentence?

Oh boy, that fiasco. It was the burning topic on the SNES boards on GameFAQs for a while. The topic was mostly ruined by a pair of obnoxious clowns named Villain and Aussie2B trying to take control of the whole topic, and acting like know-it-alls about the whole incident.

I’m not going to defend the chasing-the-translator-off-the-internet thing, but the word used in the Japanese script is “new half”. I think a good comparison would be “Oriental” to an Asian-American—to my understanding it used to be perfectly acceptable as a polite term, but these days it’s viewed as dated and may cause offense in certain contexts. It certainly doesn’t have the intentional dehumanizing malice that “tranny” does though.

I don’t blame the translator here, he clearly didn’t know and wasn’t expecting that level of backlash. I do think he probably should have done some research first, though. Even outside the realm of translating, it’s usually a bad idea to write about something you don’t know at least a little about.

Well, I’m not really blaming him for making a mistake – even though he should have realized that with a sensitive topic like this, some reasearch beforehand might have been a good idea. But we all make mistakes and shouldn’t be attacked for them if we act accordingly afterwards.

But I do blame him for the way he reacted. Not only didn’t he acknowledge the problem after having it pointed out, he got angry about the very idea of doing something wrong and instead of dealing with the situation at hand or even correcting the translation, he instead chose to just run away. This clearly shows that he wasn’t considering trans or queer people at all when translating.

Yes, there was some abuse thrown his way by angry people, but if he had reacted differently upon being called out for his pretty horrible translation, those reactions would have also looked differently.

That said, the term he used in the translation was never a good or even neutral one, it was always a slur. I do not think it can be compared to the term “oriental”, only to similarly harmful words like the N-word or the F-word.

“Oriental” at least had a history of being used without malice – sometimes it was even intended as praise for “exotic” people, even if it was quite problematic for how it treated all people from Asia as a uniform and strange mass.

He didn’t get angry, I don’t know where this interpretation keeps coming from. I don’t even think it’s possible for Tom to ever get angry, he’s like the ultimate pacifist. He was put on the defensive because a word that was in common usage a decade ago was now forbidden and dangerous. People were calling him hateful things when he had no hate of anyone in the world.

And you can call it “running away” but when you constantly try to explain to people that you didn’t mean something out of malice and no one believes you, it puts a damper on your motivation to hang around. He did ask for the word to be changed afterward, but it was already too late for the mob.

How can someone even know they need to do research on a single word amongst the hundreds of thousands already in the game? You basically work from memory and experience.

You say “yeah, there was some abuse” but then still expect him to have reacted favorably? He had friends suddenly turning on him, and strangers making character judgments on him and spreading slander. How would anyone else react? Don’t excuse abuse.

“if he had reacted differently upon being called out for his pretty horrible translation, those reactions would have also looked differently”

I’m pretty sure his own reactions too would have looked differently if he hadn’t gotten mobbed and harassed over one disagreeable translation choice, you know?

To clarify, I was comparing the Japanese word “ニューハーフ/new half” to “Oriental”, not “tranny”.

Meanwhile,us Americans have seen Okama with South Park and the GameSphere.

It’s a tragedy, what happened to Yakuza.

I don’t know what kind of brain rot’s gotten to Sega, but I hate what it’s made of them.

I don’t understand what problem is?

I still don’t get it?

Neither do I. They’re still perfectly great games.

Imagine if they tore pages out of classic books because their content doesn’t fit with modern sensibilities.

Ah, they’re referring to the content removal. Well, it’s certainly unfortunate, but I don’t think it’s something to accuse them of brain rot over. Then again, appearently I’m wrong for not thinking Game Freak is a joke for not including all the Pokémon in newest games, so maybe I’m just unusual.

Dude, it’s the removal of a few side-quests they thought people might be offended by, not a total re-write of the whole damn story…

My dude, it’s not a tragedy.

Are the Magypsies ever referred to as Okama, either in-game or by fans?

Huh. This is a good question.

I checked, and no, the term is never used in the script. I checked the big Itoi interview did with Nintendo Dream too, and it wasn’t used there either.

This is one I’ve only heard about through the grapevine, though the facts add up:

There was a Japanese Game Boy game called Robopon that was fairly infamous back in the day both for the way it ripped off Pokemon and its strangeness. (The cartridge had a built-in speaker and an IR reader that interacted with remote controls to do things in-game, for example.) One of the monster lines in the game was a suspiciously phallic-shaped monster that evolved into a peach. The final form was an unflattering, heavy-chinned robot with a bow that allegedly went by the name Okama in the Japanese version, though I haven’t seen it to confirm the name. The Western version just called the robot Apebot, and edited the phallic-looking robot to look… less so.

Robopon had a much cruder sense of humor than Pokemon did. The tie-in comic, which was also in Comic Bom Bom, featured large-breasted women with visible nipples under their clothing and a LOT of sexual jokes. Clearly this one didn’t sit right with everyone, though, because that particular robot was removed from the special edition of the game. The phallic and peach-like robots remained, but they weren’t connected any more, as far as I know.

I really appreciated that you wrote this article. I’m utterly fascinated by this kind of cultural history or baggage of Japanese words or phrases that we never have gotten to realize from the other side. This sort of thing just begs for its own kind of Sociology or Linguistics textbook, geez. I wonder if the Persona series or Catherine have ever made any references to オカマ…

In fact they did. Persona 5 at least has this bar you can visit tended by a drag queen. In Japanese, this bar’s known as Nyukama which is apparently a pun on newcomer and okama.

Whoa, Eijiro on the Web Pro! Just covering all your bases? I’ve never heard someone be called a “fruitbar”.

Eijiro is interesting in that it unlike your ordinary language dictionary, this one relies heavily on actual quotes/translations found in various media. In other words, a lot of those entries were likely from English-language entertainment, articles, shows, etc., and okama was how it was translated into Japanese in those situations. Eijiro doesn’t work entirely that way but it’s a big part of it. I love it because I never know what I’ll run across, one minute I’ll encounter Japanese/English quotes from the Full House TV show, and then Oscar Wilde books the next.

Wanna provide a link to that site in question?

The Pro version costs money to access and has lots more stuff, but here’s the free version: https://www.alc.co.jp/

Whoever is responsible for the localization decision to put Dragon Quest games into flowery pretend-Shakespearian English ought to be fired

It’s only I and II, and the modern translations of I and II do it to match the NES translations. This woman has that style in XI because she’s a reference to a character in II. Most of everything after III is not in that style. (Also it’s way less full of errors than most things that emulate that style are, which I appreciate.)

But why? It really brings the world to life and it’s fun to quote. I quite enjoy it personally, and so do a lot of folks.

As someone whose first language is not English, I hated it as a kid. I hated it soooooooooooooooooo much.

Wholeheartedly disagree. I think it was a great choice and I find it incredibly charming to this day. They deserve a raise and a promotion.

What I’m more surprised by is how the NES localizations went out of their way in technical work, reprogramming menus to have proper English, even including things like word-wrap (at least in DQ2).

Comparatively the GBC version menus look like the most amateurish of fan translations. We have items like “LoraLuv”, seriously? Pretty sure we had plenty of options like MGC and EQIP too. 😛

So you’re saying the late Satoru Iwata should be fired? Cuz he spearheaded the localization of the very first game and was the one who decided to used that style of speech.

To be fair, it’s not an “only one or the other” sort of thing. The original DW games did have archaic speech, but to a much less degree and often only when it fit the character or situation. The more modern translations of the games have *everyone* speak that way, and to a much greater degree. Here’s a random NPC from DQ2:

Basically, it’s a weird argument to say they’re the exact same. One is archaic when needed, one is archaic hyper mode.

EDIT: Now that I think about it, maybe this would be another good “which do you prefer” survey articles.

Yes, please.

Spoilers to Dragon Quest Builders 2:

In builders, the world is set after the game of Dragon Quest 2 by some amount of time, and most people speak in a ‘mostly modern but slightly fantasy’ English.

But characters that are from the actual Dragon Quest 2 time period still speak in ‘Ye Olde Englishe’. I think it’s an intentional and somewhat clever choice, in that it makes it seem like there’s been a lot of time to pass and some language shift. And it adds to the apperance of a direct continuity.

I empathize though with people who had a hard time understanding it due to English not being their first language, that said.

You know, if anything from looking at both games (I’m in the process of porting the modern scripts into the old games) the old scripts strike me as High School Level Shakespeare (and having space restrictions) while the new scripts seem like they’re more authentic (and not having to deal with space restrictions) I really enjoy it myself, but I feel for non native English speakers that must be a pain.

There is a fashion store line here called “Mister*Lady” (because they sell both male and female fashion)

I can only imagine that it would cause some confusion for Japanese visitors.

I am amazed there was no mention of One Piece and a certain character anywhere in this article.

Yeah, I felt the article was already too long, plus I wanted to focus on games here. I plan on adding a gallery of other examples (including non-game stuff) that’ll go on a separate page.

Also, I’d say with One Piece it’s more than just the one character, it’s a big ol’ group! Oda really went all in with the okama stuff, it’d be interesting to trace how it’s been translated in the various manga and anime releases over the years too. I believe I usually went with crossdresser back in the mid 2000s, but I recall seeing other translators using other choices.

Gintama was another series that had heavy use of okama; one of the major factions of the city is entirely made up of them. Early episodes in the series are subbed to use some uncomfortable slurs when referring to them, but they sort of stop playing it purely for laughs and I think the harsh language went away by the end of it. Could be a good example for how a series changes how they address the same character more than a decade later.

I forget how Funimation handled it in the anime, but Viz made some rather creative choices with the manga. There’s actually an interview with the english editor from during the Alabasta arc where he talks about how tricky it was handling that controversial stuff here: http://www.onepiecepodcast.com/2018/07/20/opreadthrough-4-baroque-works-part-two-2/ . Not only does he talk about the “Okama way” text on the character’s jacket, but also mentions almost translating his devil fruit as Trans-Trans Fruit for a pun, before realizing it was a bad idea.

Okama actually comes up a bit in the manga One Piece. There is a character called Emporio Ivankov self proclaimed king of the okama. To the story as a whole he isn’t a major character but is important for an arc or two. He is portrayed in a joking way and has the power to change genders, both his own and other peoples.

It’s been some time so I don’t remember how the word was handled, I want to say I think it was just left as okama. Given the time frame I also can’t remember if I would have been watching/reading official translations or some type of fan translation.

Isn’t he more or less based on Tim Curry’s Frank N. Furter?

What I found oddly fascinating in One Piece’s handling of Okama characters was how all over the place it was. (spoilers to One Piece follow)

On the one hand, you have Ivankov and their whole fanbase/army of queer-coded people and furries, who are all painted in a very favorable light, even if they are clearly strange and a little over the top or slightlycrazy, they are always shown as nice people.

Mr. 2 who we meet the first time much much earlier was at first presented in a way that framed his clothing choices and behavior as abberant – until he switched sides and everybody suddenly liked him. When he returns in the story around the same time as Ivankov is introduced he is just a force for positivity.

So we might assume Oda simply evolved his views on people who don’t conform to their gender stereotype and/or queer people …..

But around the same time Ivankov is a major character, we have a whole sub-plot of Sanji the womanizer, super straight guy being stranded on an island full of Okama that very aggressively try to basically … assault him for months, playing up some really harmful stereotypes about queer people as dangerous predators. Constantly fighting them off is his version of the “advanced training” every character gets. Which is just weird on so many levels.

How do these two protrayals exist in the same story? Especially coming after a really inclusive portrayal?

I am still flabberghasted over that.

Ivankov is based on a friend of Oda’s who’s an actual celebrity “okama”. I assume some of the changes as it goes on were positive input from him and negative input from Jump editors thinking what 12 year old boys thought would be funny.

His friend actually used to voice Ivankov in the anime! Until one day the police arrested him for “obscenity” and he was fired.

I just got into One Piece again recently and I had the same thoughts!

I feel like Sanji thinking of the Kamabakka kingdom as hellish because there are no girls there could be played as a joke without being offensive if it were entirely at his expense (though it’s possible that his views could be viewed as invalidating towards trans women regardless…), as in, he WASN’T constantly being assaulted.

I also think it would’ve been nice if he had embraced something of a “feminine side” due to being on the island, especially since the jokes about him seeing women again after he came back felt like they became old hat really quickly. It doesn’t need to be a huge character change, but at least giving Sanji some genuine respect for the okamas would’ve felt better.

This is a great article and I really appreciate all of the research that you did. But my biggest takeway is… the “no Dragon Quest releases on weekdays” law was just an urban legend!? I’ve gone my whole life thinking that was totally a thing. I could have sworn it was even referenced in official publications like Nintendo Power or US Shonen Jump. Goes to show how easily that kind of misinformation spreads, especially back in that early internet era…

I’d be curious what actual LGBT+ groups in Japan have to say on the subject.

There’s an early episode of Pokémon that briefly had a rather flamboyant fellow show up to pick up his pet from a grooming appointment and in the production notes, the fellow is referred to only as “Okama”. He’s on screen for less than five seconds if I recall but he was fairly memorable and Misty stared at him. I don’t know what any dubs would have done or what he was called in the physical scripts since he didn’t have a name, but it would be interesting to find out. It’s the episode where Brock met Suzie and got Vulpix.

Hey Clyde, thank you so much for this article. I can’t speak on the Japanese notions of the word, as I’m American; but I am queer and have been at the receiving end of a fair amount of derogatory treatment. It’s always a relief when language education of any kind addresses slurry, derogative, and pejorative terms and their context/ history instead of just acting like they don’t exist.

In South Park, the Okama Gamesphere was a game console introduced in one of the earlier seasons that resembled a mix between an Xbox, PS2, and Gamecube, the big three consoles that were new at the time. South Park: The Stick of Truth has one you can find in someone’s house – turning it on starts it up, it announces its name out loud, and goes to a perpetual updating screen. That’s all it does. It’s just an easter egg, as that game’s full of all kinds of easter eggs for South Park fans.

I don’t think there’s an official Japanese translation for Stick of Truth, but is there a fan translation? If so, how did they handle it? (or how would they handle it?)

Danganronpa V3 had an instance of it that was translated as “girly”.

https://i.imgur.com/gZKI0GO.png

https://i.imgur.com/0Yt5yc9.png

I am queer, so I’m not incredibly interested in facing homophobia or transphobia when I play games, but I don’t know how to feel about the translation choice. The character is a hot-blooded ‘macho’ type raised by his (presumably very traditional) grandparents, and expresses a lot of toxic masculinity and homophobia elsewhere that appear to have been similarly ‘toned down’. It feels like as a “big hero” character, his flaws have been more sanitised, especially when contrasted with the translation apparently also making a same-sex-attracted character both less sympathetic, and less openly non-heterosexual.

It’s tough to tell if this is a case of the localizers wanting to maintain Kaito’s appeal to players as a likeable protagonist by downplaying the blatant homophobia, or just ignoring it altogether since they thought the ‘okama’ usage portrayed the same alpha male persona that Kaito achieves in English by saying girly. I’m also wondering if the ‘okama’ usage provides stronger evidence of Shuichi’s implied bisexuality vs. just ‘girly,’ which could equally imply the perjorative ‘gay’ as much as ‘unmasculine’ or ‘meek’ or ‘nonconfrontational’, etc.

Worth noting that Danganronpa isn’t the most progressive when it comes to LGBT representation. Teruteru is one of the few confirmed bi characters and he’s a gross pervert who’s only known for being perverted (almost exclusively toward girls). Tenko is strongly implied to be attracted to girls, but she spends most of her time lusting and obsessing after one other girl which turns into borderline molestation. It’s not good – so I wouldn’t be surprised if Kaito dropping ‘okama’ wasn’t meant to be seen as a slight against him. IDK, I guess they did okay with Ibuki…

As an aside, learning Japanese now and having only played the Danganronpa games in English I’m glad they’re re-releasing them on mobile markets with EN/JP audio and text so I can go through these all again on my own and discover little things like this.

Gurumin had an instance of オカマ during the third boss fight.

Japanese video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZFnpZMpI8Co

English video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tfMNpLTW0j0

Here is the dialog:

パリン「オバサンンこそ邪魔しないで」 / Parin: You’re the one in the way, lady!

ラッシー「…し、失礼ね、ぷんぷんっ!」 / Roger: Lady?! How dare you!

ラッシー「オバサンじゃなくてオ・カ・マよ!」 / Roger: My mother, she’s a lady.

ラッシー「あの小娘といい、このお嬢ちゃんといい…」 / Roger: One day you’ll understand.

And afterward, this sequence happens:

パリン「なかなか手こわいオカマだったわ」 / Parin: I thought I might kick the bucket.

チャッキー「おかまって、これ?」 / Chucky: You want a bucket?

パリン「…………」 / Parin: No, I didn’t have a chance.

チャッキー「これ?」 / Chucky: Pants?

パリン「それ、ハカマ」 / Parin: I thought that was the end!

I remember that fight. Roger was the most entertaining of the phantom bosses.

“In the Japanese version, we can see that the original okama reference was carried over into this new release. In fact, new text was even added to intensify the character’s displeasure.

In the fan translation, we can see that okama was translated as “homosexual”. The full line itself, though, was mistranslated. As a result, the character now appears to insult you, the player, by calling you a homosexual.”

I think you might have misinterpreted the translator’s intent.

I get the impression that they weren’t translating “okama” as “homosexual”, but rather they were sidestepping the issue entirely and making a joke that the okama character was assuming the player’s reason for *refusing a puff-puff* was that the *player* was gay, and thus not interested in a woman’s breasts.

To be honest, judging by the sheer number of mistranslations in all the Dragon Quest fan translations, I honestly do believe that they didn’t actually understand the original line.

For one more non-video game example, in One Punch Man, there is a character named Okamaitachi.

https://onepunchman.fandom.com/wiki/Okamaitachi

As seen in the webcomic, he has a tendency to fall for monsters :

http://galaxyheavyblow.web.fc2.com/fc2-imageviewer/?aid=1&iid=63

Who can blame him? Monsters are hot. <3

As a gay man myself, it is always fascinating to see how these sorts of gender and sexuality issues are handled in other media.

“Okama” is definitely a term that is used both derogatorily and yet playfully as well. I think that it’s a good choice to simply leave the phrase untranslated. After all, it is not uncommon for certain terms to be left as they are. Like, everyone knows what a bishounen is without having to say “pretty boy” instead.

Still, one can’t help but notice that most okama-type characters tend to be villains. Seriously, if I had a nickel for every villain in Japanese media who’s an effeminate dude I’d be able to buy a copy of DQ11.

Although thinking more about it, okama tend to be comic relief just as often.

Both still very reductive of them to keep getting pigeonholed into.

The feminine villain thing was popularized by a Chinese wuxia villain named Dongfang Bubai (aka Toho Fuhai aka Master Asia).

I think there’s also elements from kabuki in some characters like Sephiroth.

Oh my god that mobile DQ loc job almost made me barf in my mouth

You might want to see a doctor about that, weirdo.

There’s also derived form of okama I’ve seen that doesn’t really have a widely-accepted translation either: nekama, a portmanteau of (inter)net and okama. It’s used to refer to men who present as a woman exclusively online. A rough English equivalent would be “GIRL (Guy in Real Life)”, but it’s rather unwieldy and isn’t really used in direct address like nekama is.

There’s also the word “catfisher”, of course, but that doesn’t have the explicit gendered meaning nekama does.

The word was used on the virtual message board in the game Akiba’s Trip: Undead & Undressed, and it was controversially localized into English as “trap”. The word “trap” is most commonly used in real-life English message boards to refer to a certain type of fictional, male-identifying crossdresser that can pass for a young girl appearance-wise; it’s not exactly the same meaning-wise as nekama. It’s also sometimes used as a pejorative slur to refer to real-life members of the transgender community. The localization specialist responsible, however, continues to defend this choice to this day, arguing that it was the most natural-sounding alternative he could think of. I somewhat sympathize with him in that regard, but there had to be a way to phrase it that fit the actual meaning better.

I know it’s not the point of the article, but the sudden, hard shift in the Dragon Quest section from straight-laced translation to heavy Elizabethan English was so goddamn funny to me – no judgement on the actual translation quality or whether its “better” or “worse,” but it was charmingly jarring to see.

Regardless, very interesting look into the way views shift over time on acceptable language in regards to minority groups. I see it happen all the time in English, and it’s interesting to see a glimpse of how that plays out in another language and culture. Makes me wonder how these situations might work the other way around – might there be interesting examples of this in English-to-Japanese translations?

Look at how Japan dubbed Beast Wars for an example of some serious off-the-rails stupidity.

I’m curious now: the Demiforce translation for Famicom Detective Club Part II (that I think you worked on?) has a character that is referred to with the word “tranny” in the English script. Was this character called an “okama” in the original Japanese script?

Yep, I checked a while back when someone asked the same question, and it’s indeed okama in the Japanese script. For clarification, I wasn’t part of the translation team, as seen in the readme. I started a project back in 2001, dropped it a few months later when I hit ROM hacking obstacles, then passed my files along to demiforce a year or two later.

With the new HD-2D version of Dragon Quest 2, the Puff-Puff girl is just straight-up gone. The Puff-Puff Girl in Dragon Quest 1 is still there, so I’m guessing it was removed specifically because of the Okama thing.