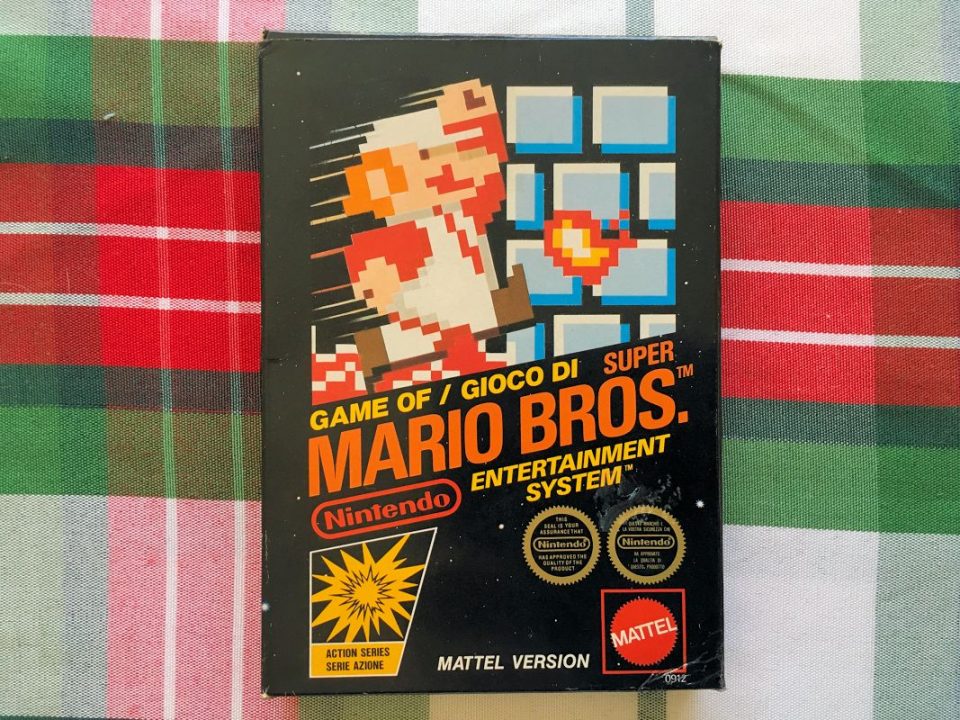

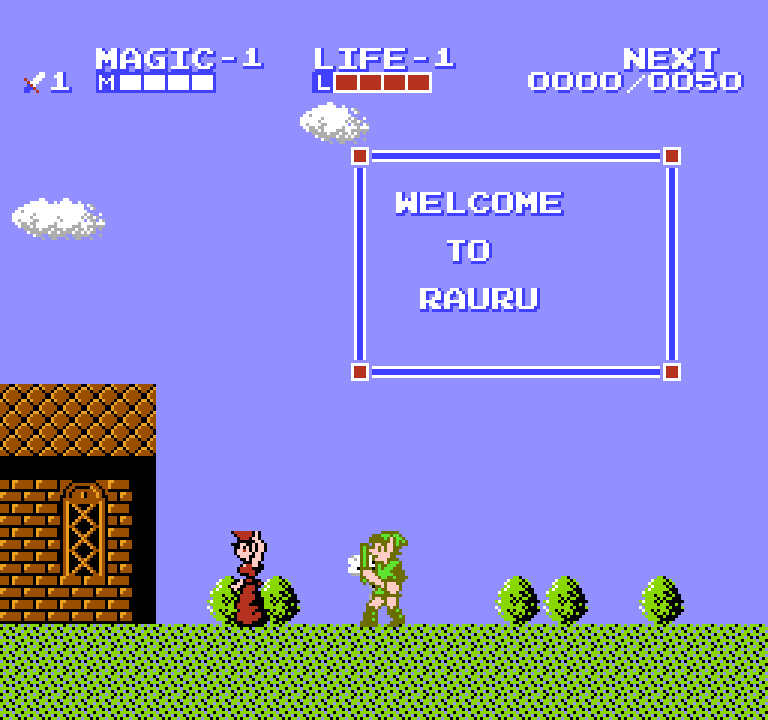

Nintendo and Mattel released many NES games in various European countries during the 1980s and 1990s, but strangely enough, they usually left the games’ text untranslated. To make up for this, sometimes the companies would translate the games’ manuals into the local language – but not always.

I didn’t grow up playing these European releases, but it really feels like console game translation in Europe during this time was in an unpredictable and frustrating Wild West era of sorts.

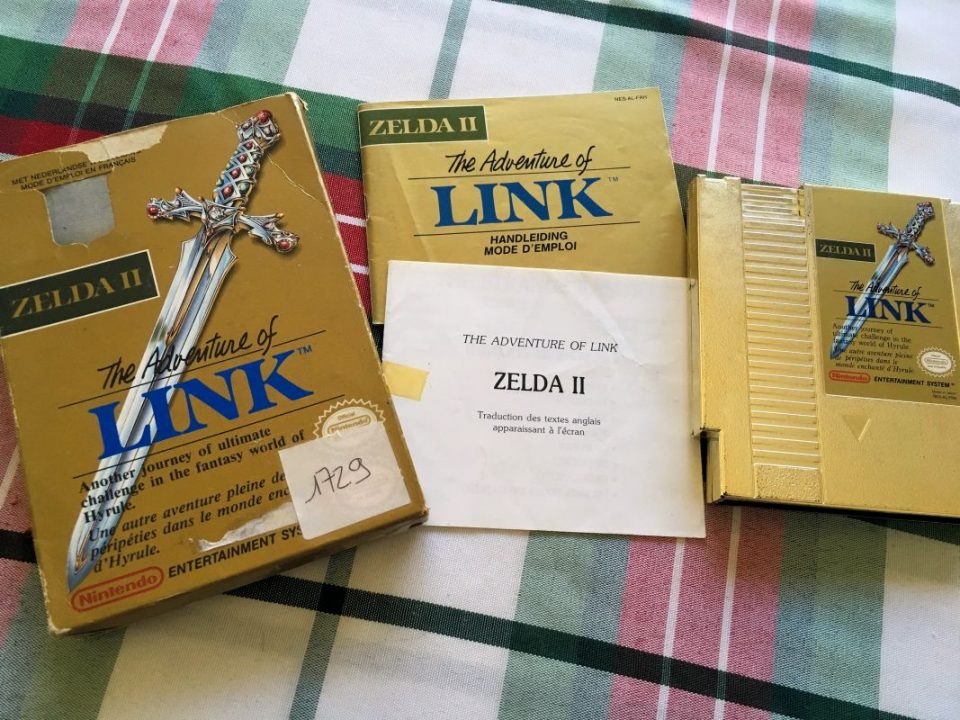

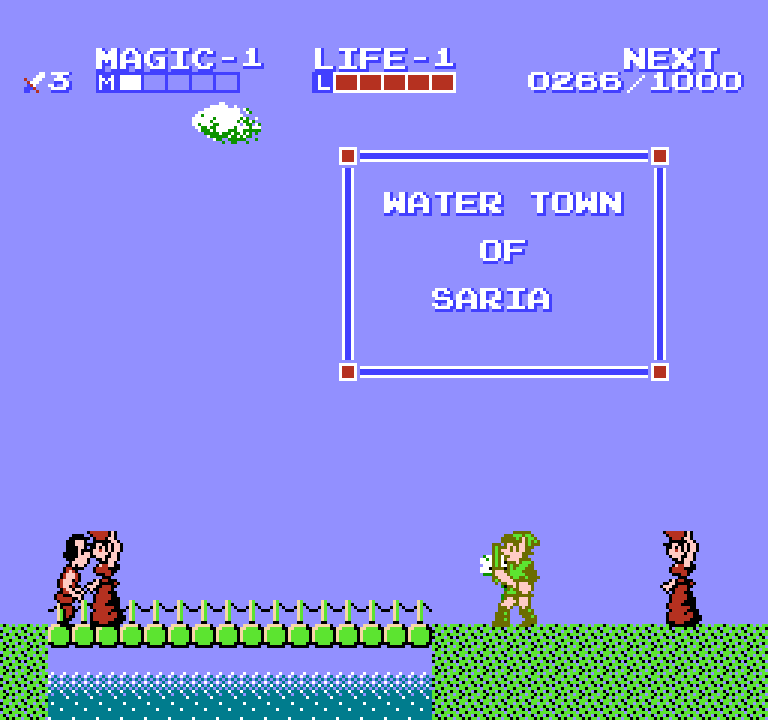

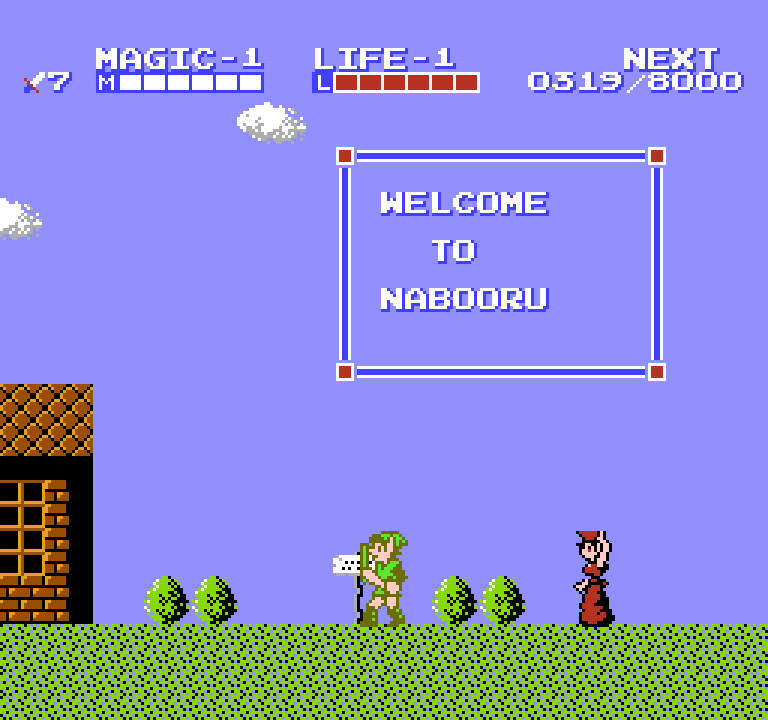

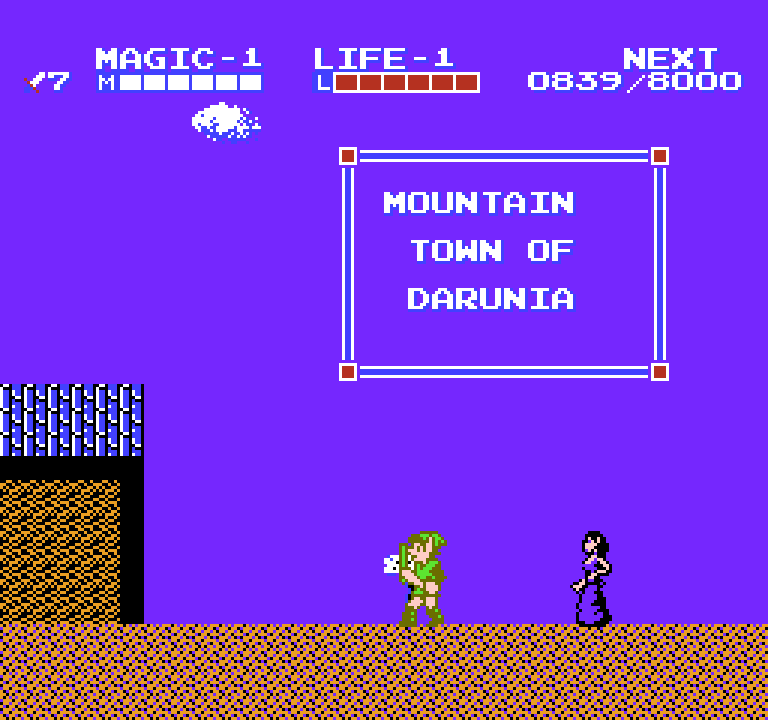

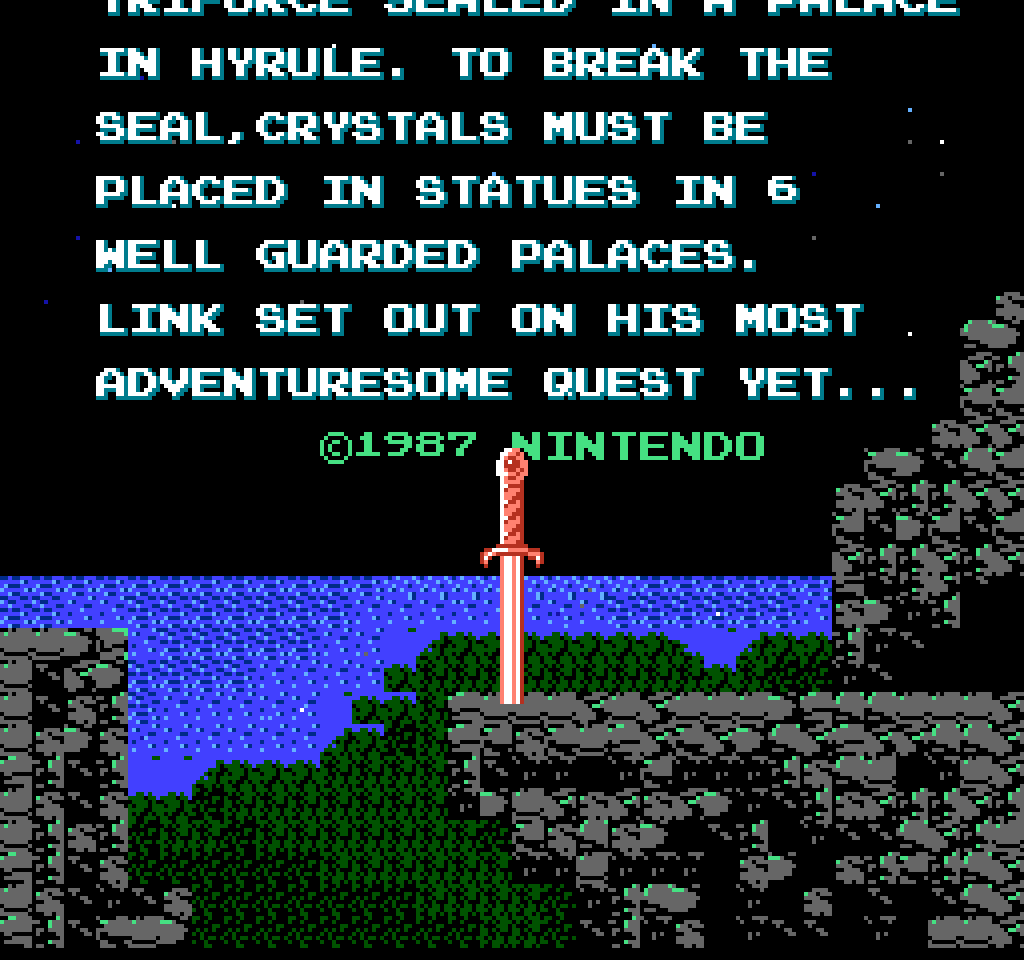

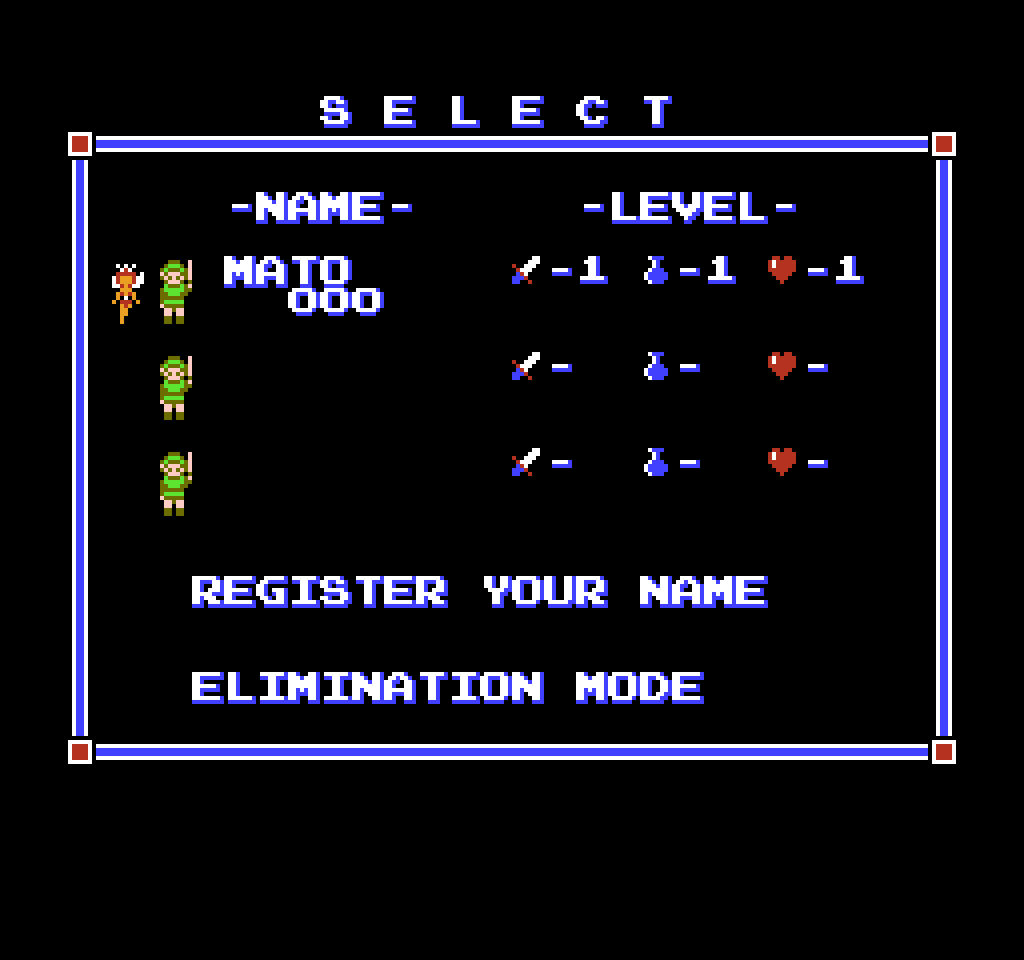

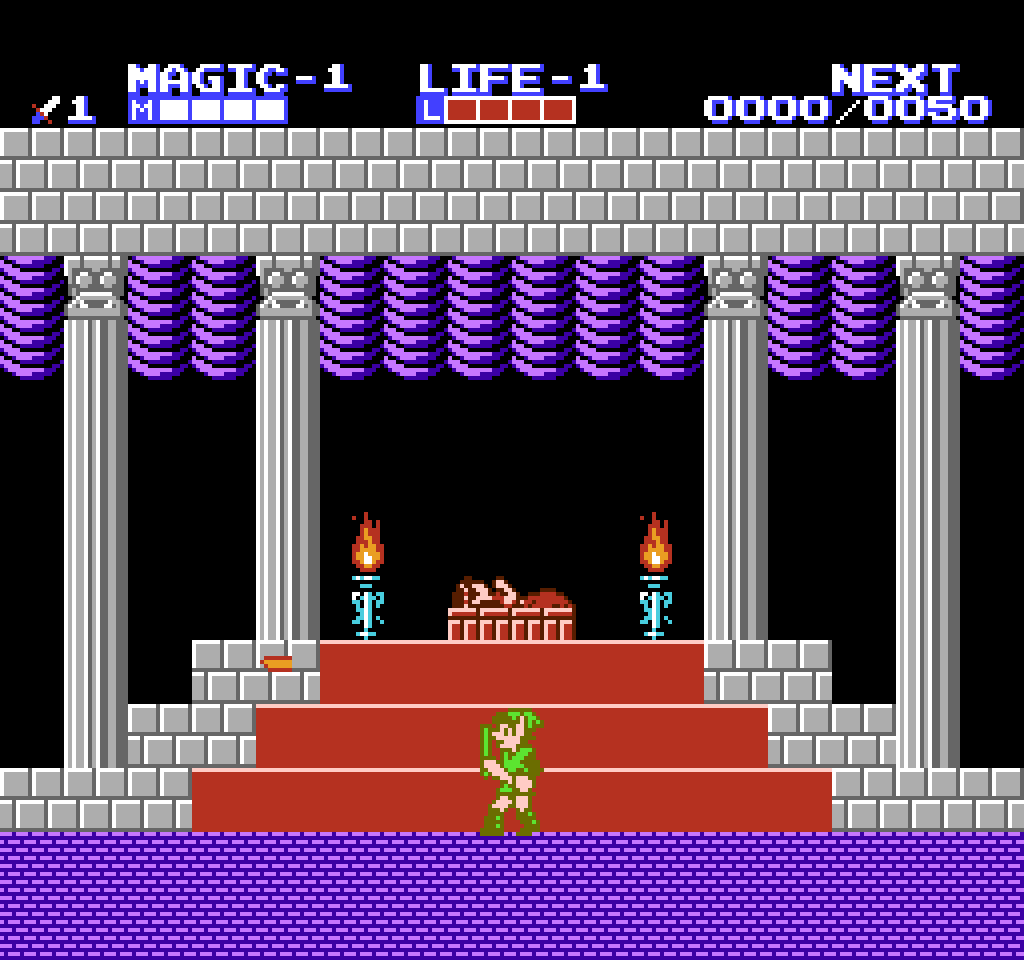

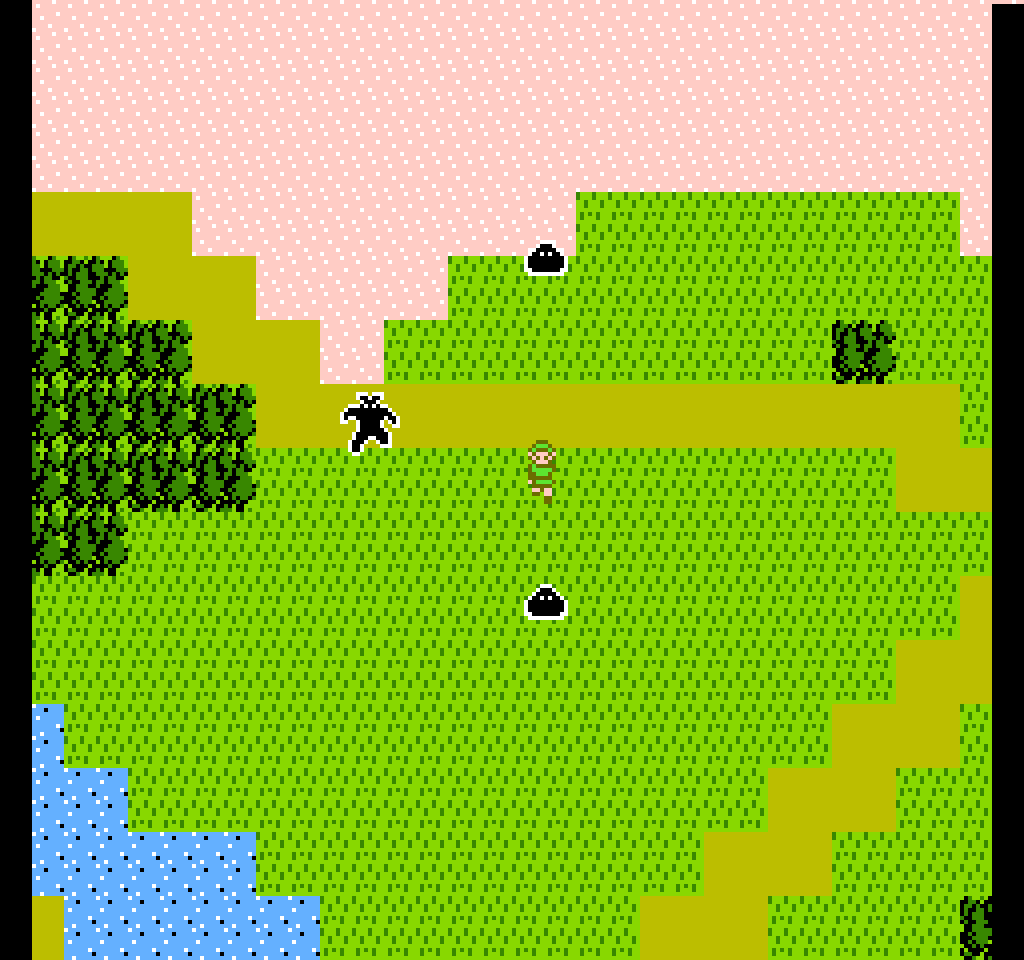

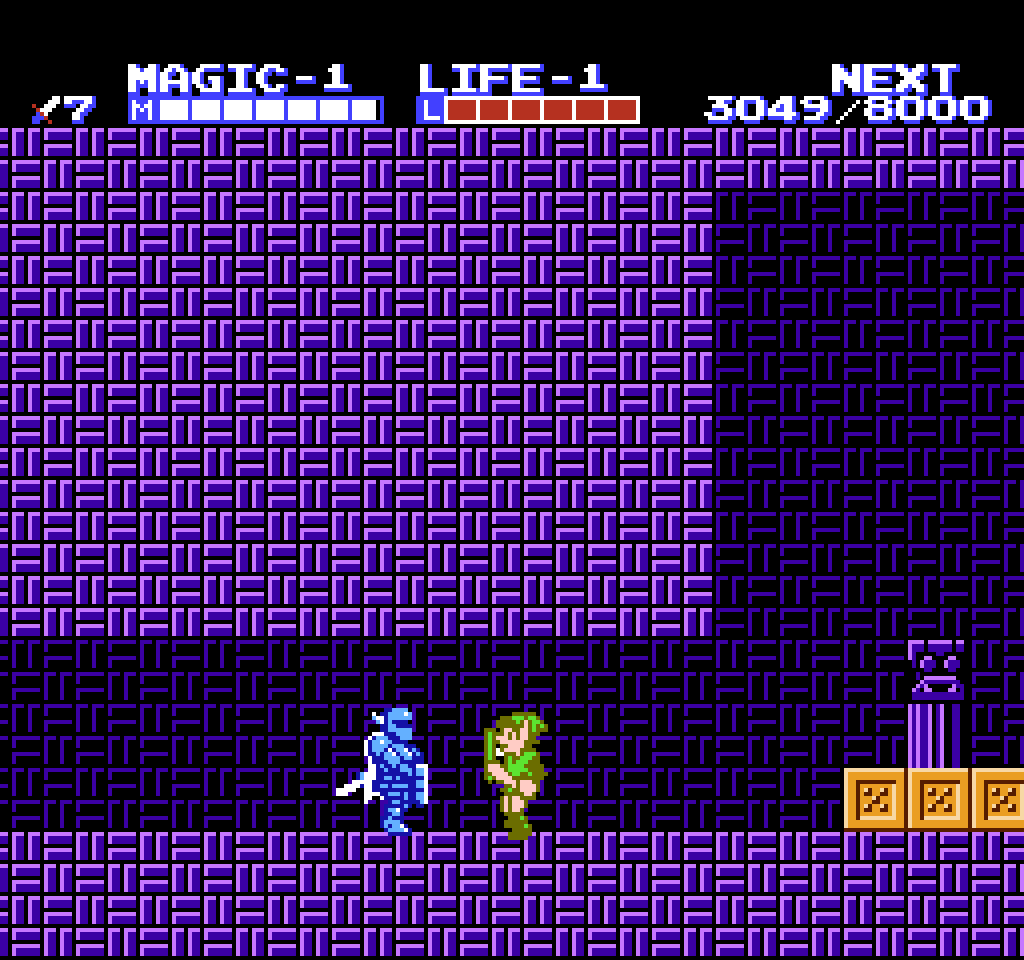

Anyway, while researching Zelda II stuff a while back, I came across an interesting find: there was a French release of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link that came with a translated manual and a booklet that translated all of the in-game text.

I’d never seen a console game get this translation booklet treatment before, so I bought a complete copy of this French version to learn more. So let’s take a look at it!

French Translation Booklet

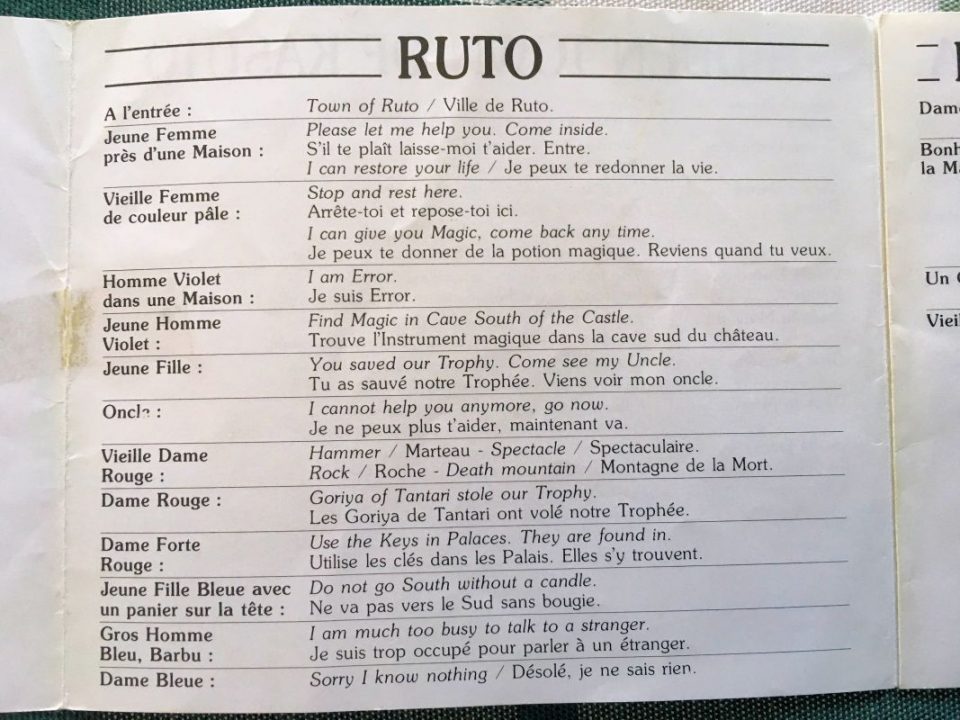

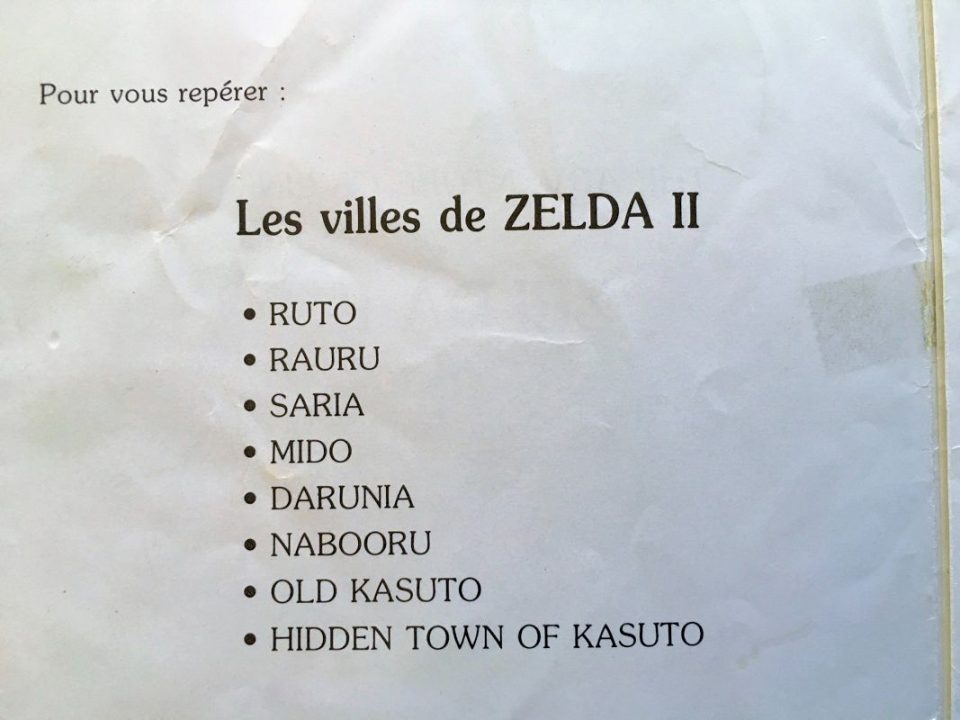

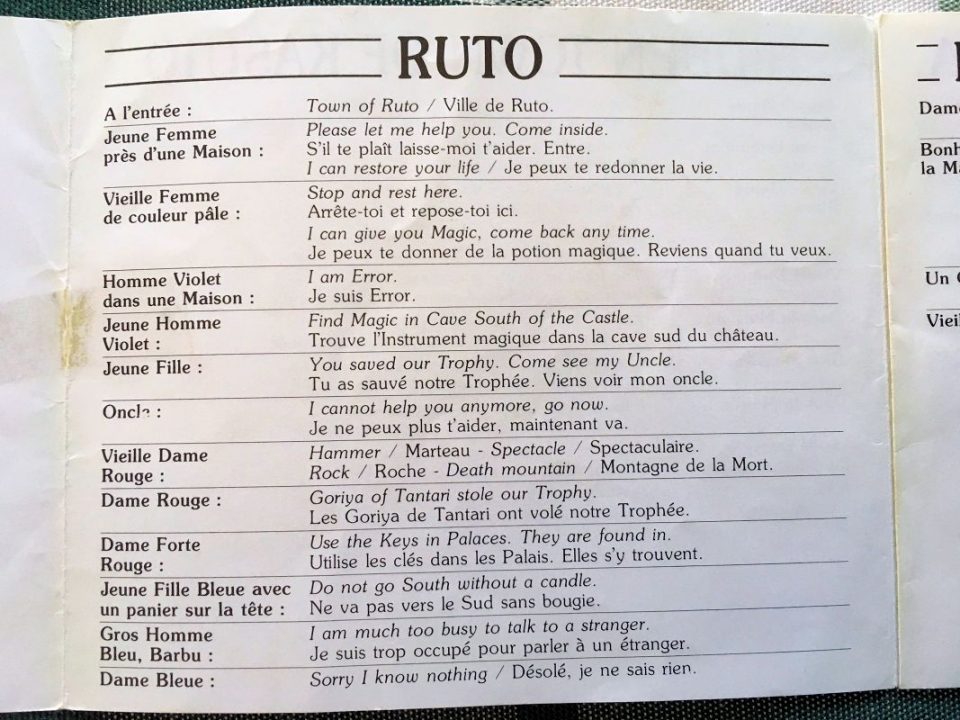

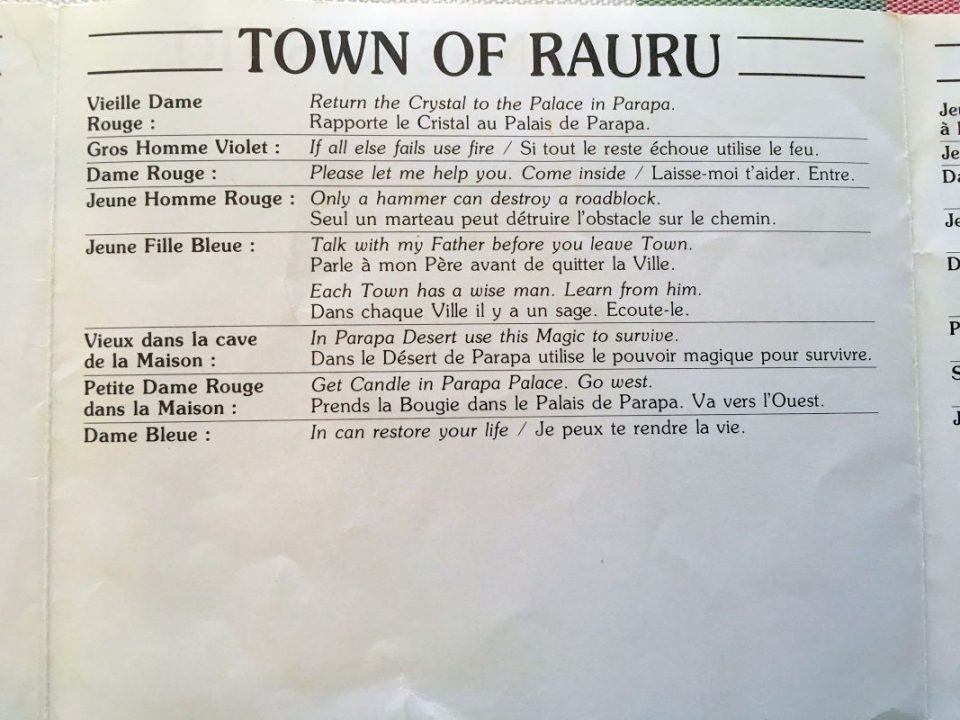

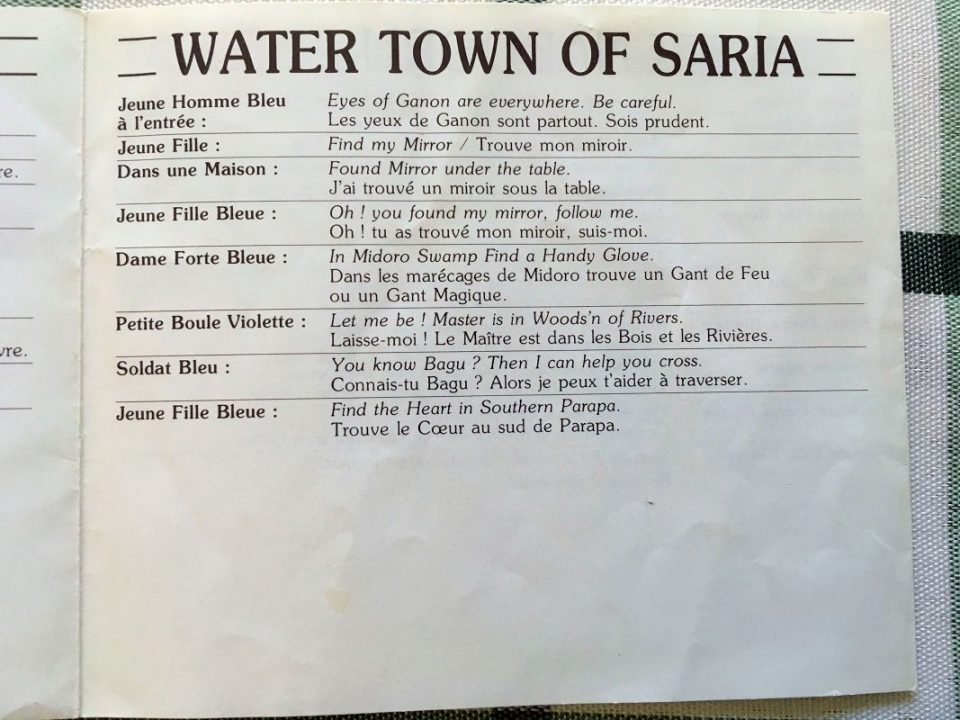

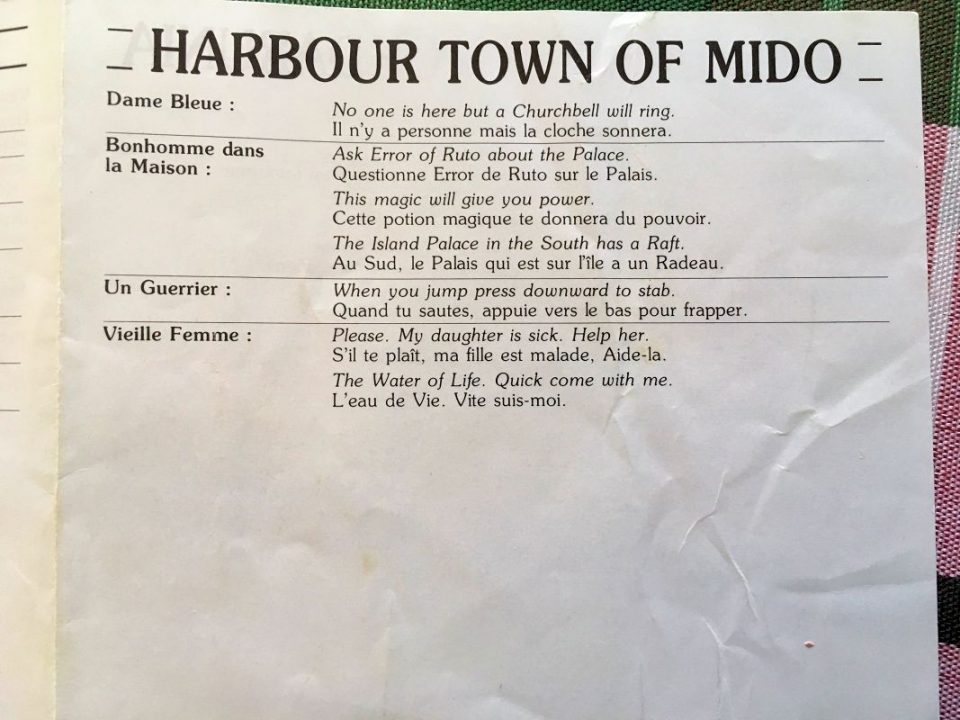

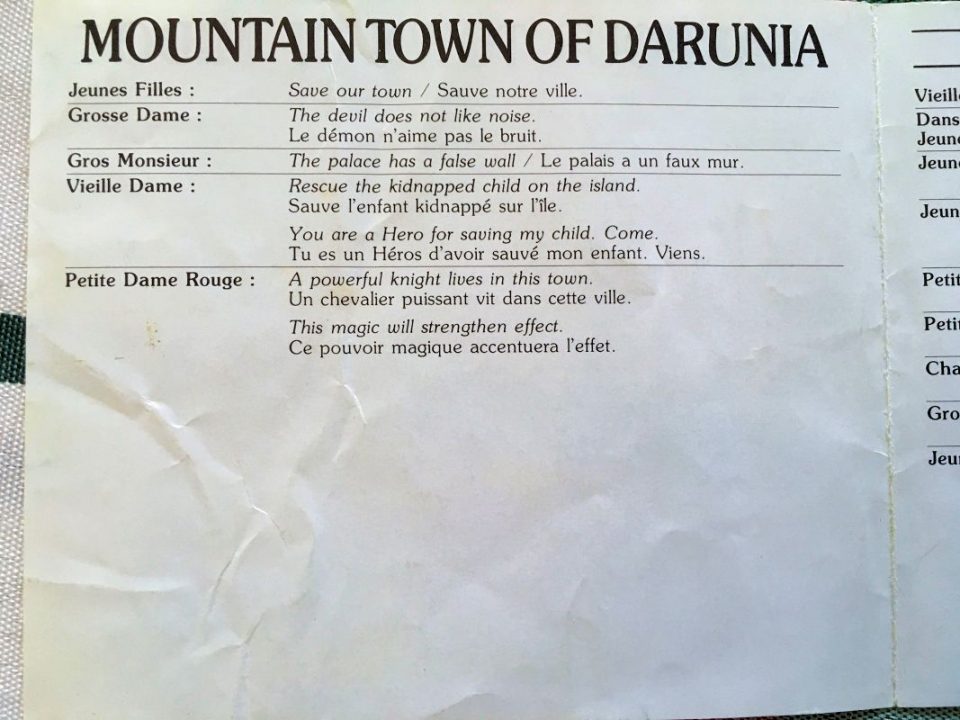

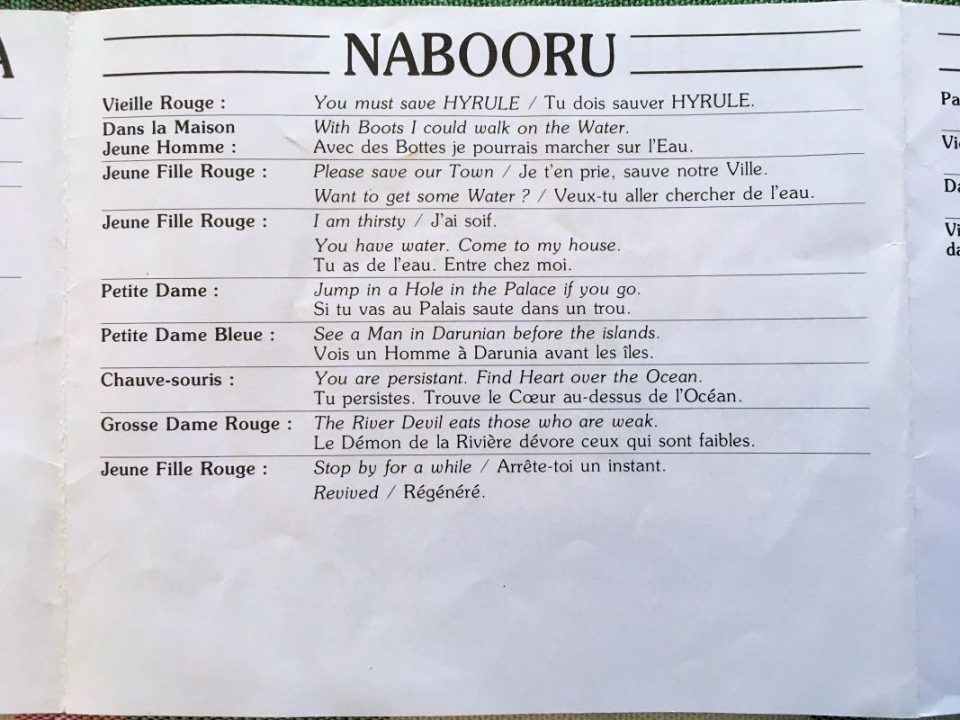

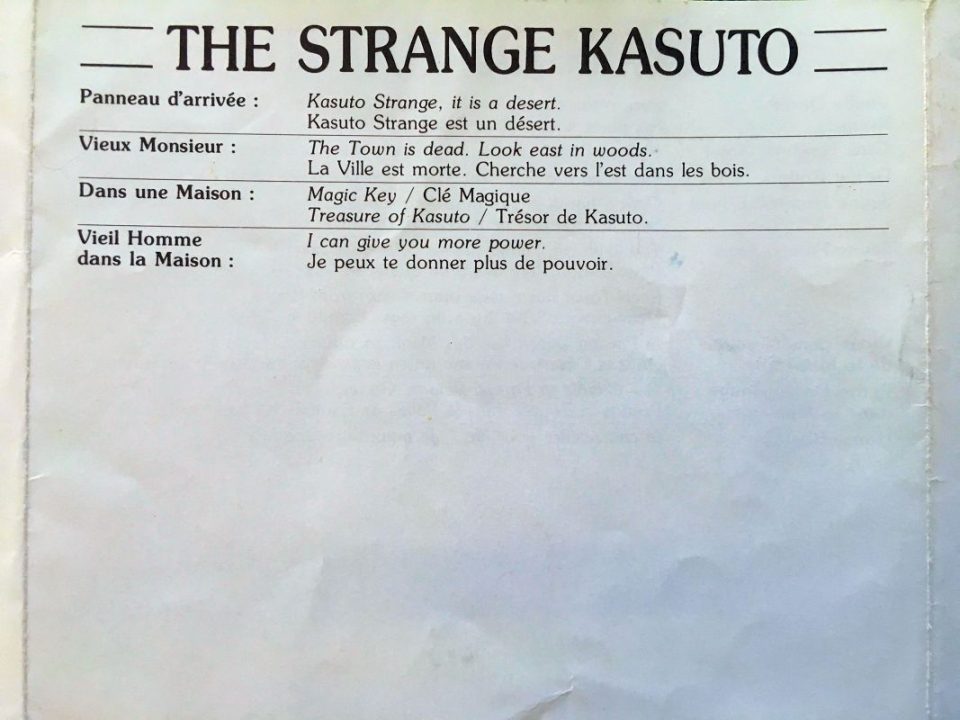

First, if you’re interested, here are photos of the entire Zelda II English-to-French translation booklet:

Translation Comparison

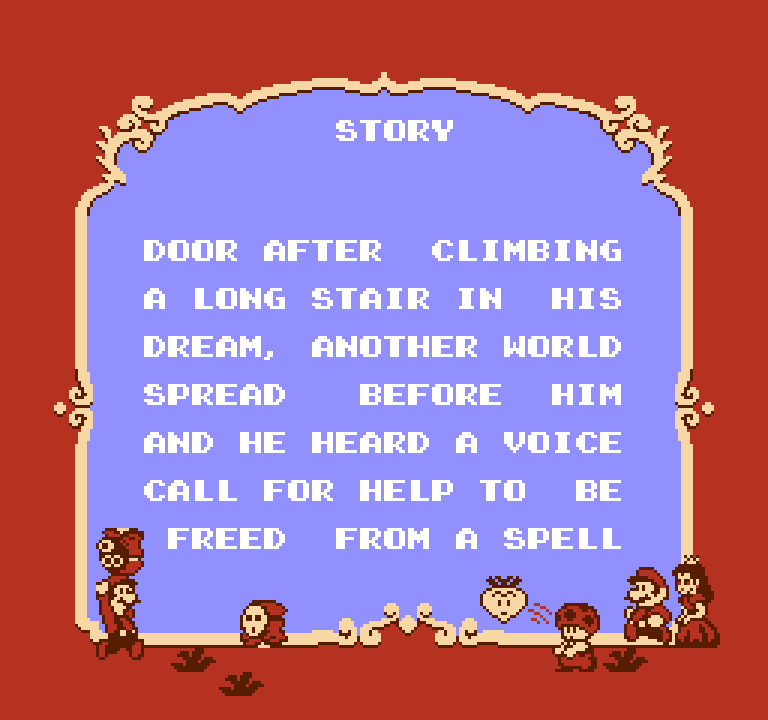

I don’t know French, but I’m enough of a linguist to recognize that there are a number of odd translation choices and translation mistakes in the Zelda II French translation booklet. So I asked two native French speakers to go through all of the text and provide their thoughts about each line, along with translations of each French line back into English.

Not every French line was noteworthy or interesting, so we’ll skip those and focus on the good stuff. Check out the booklet photos above if you want to see all the lines side-by-side, though!

Missing Translations

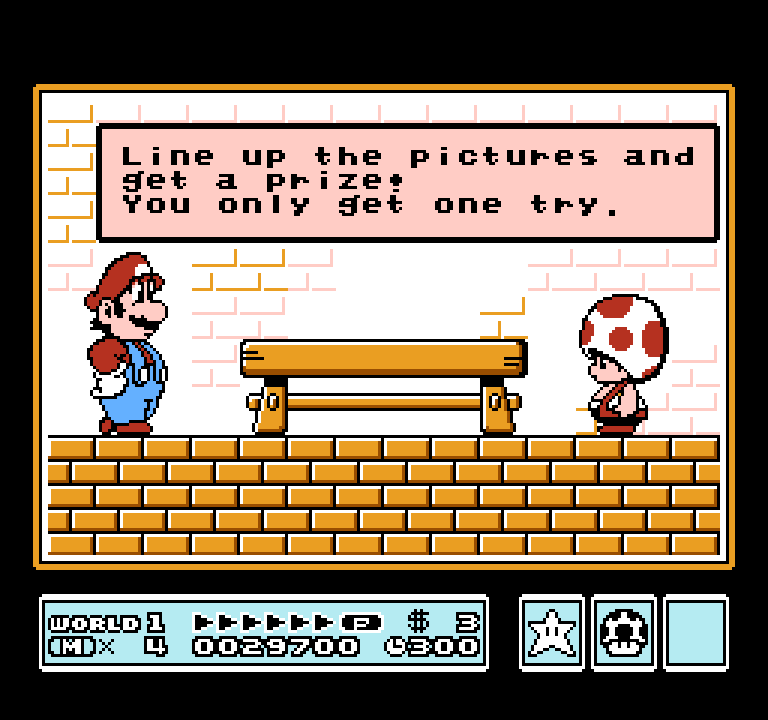

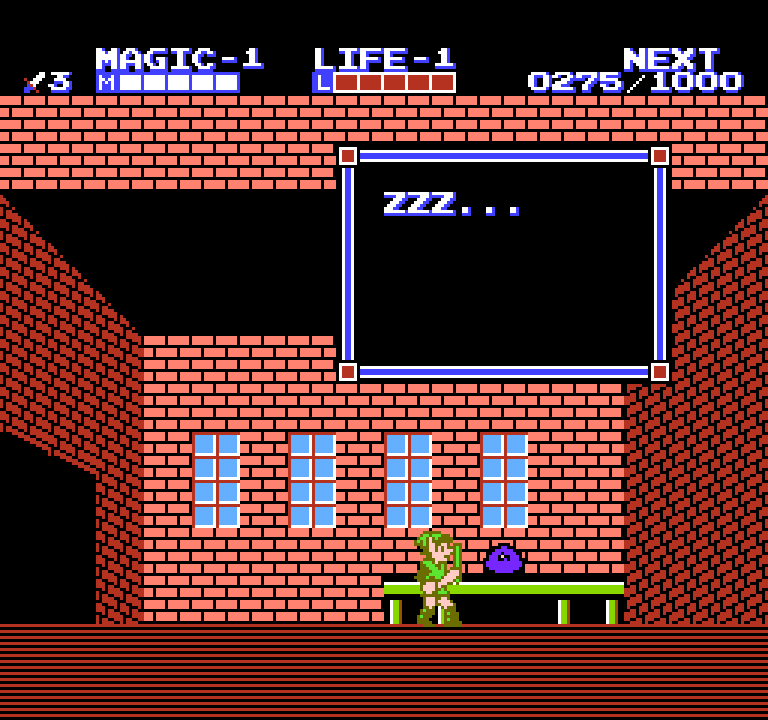

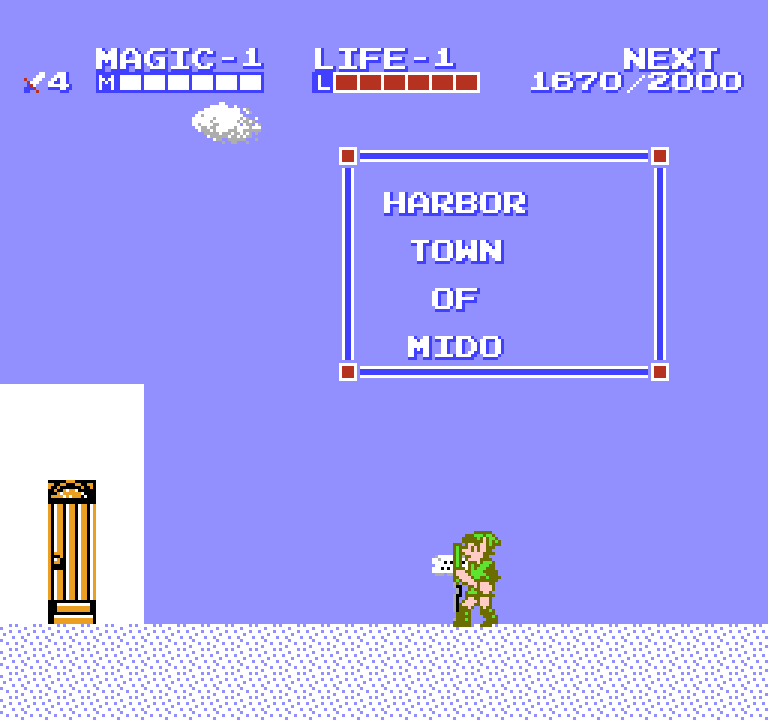

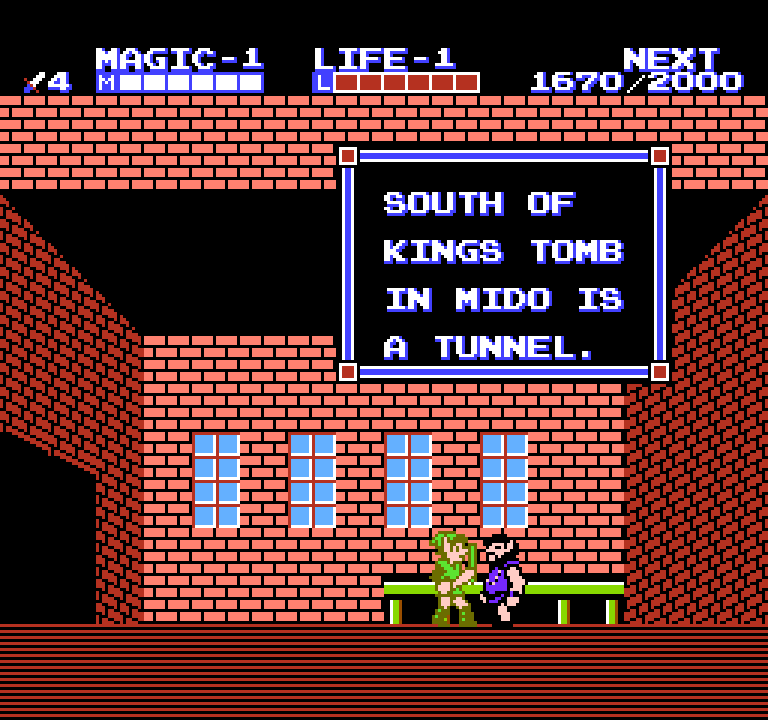

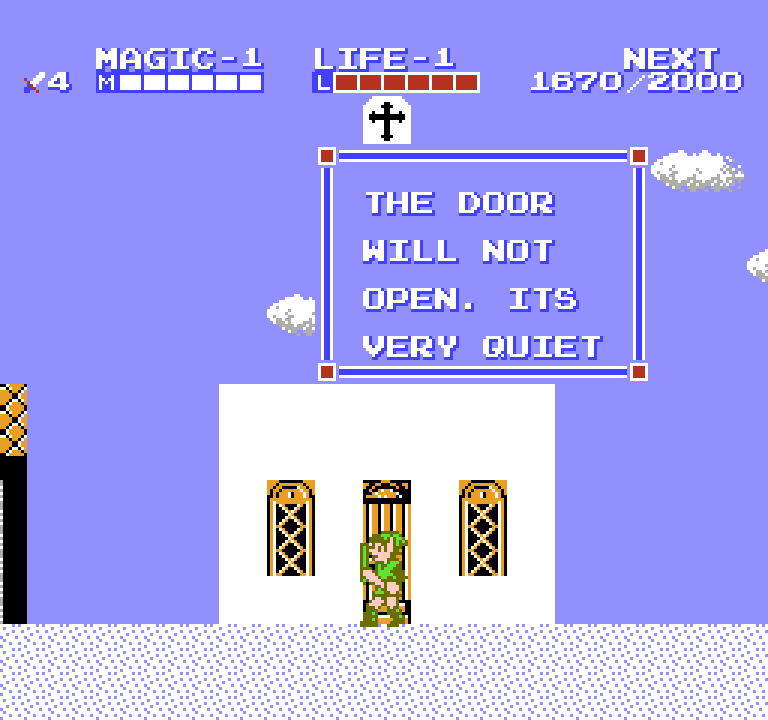

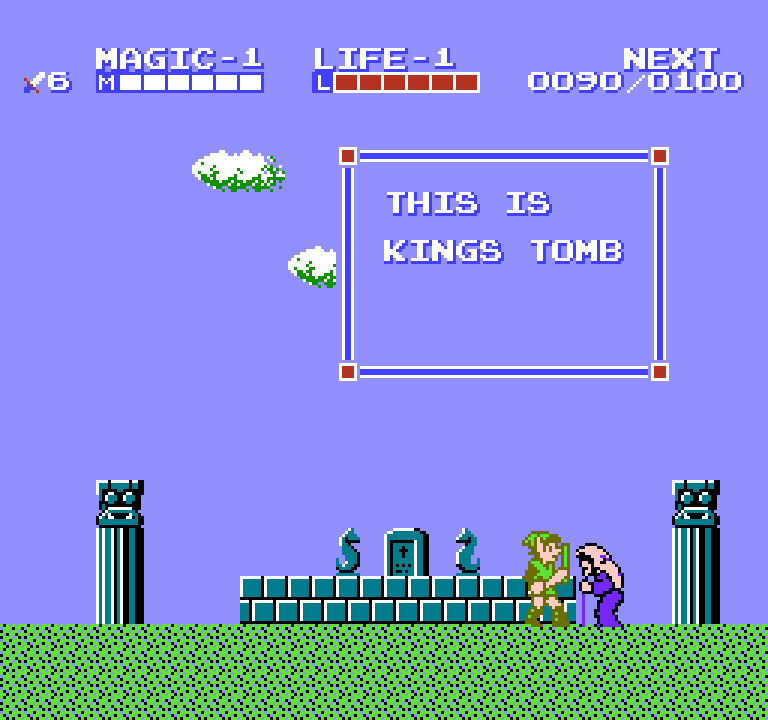

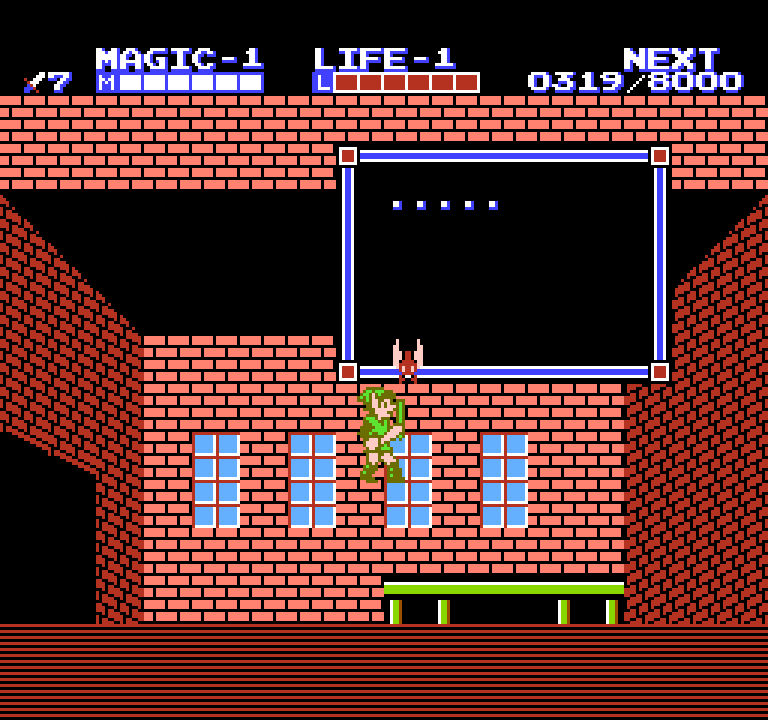

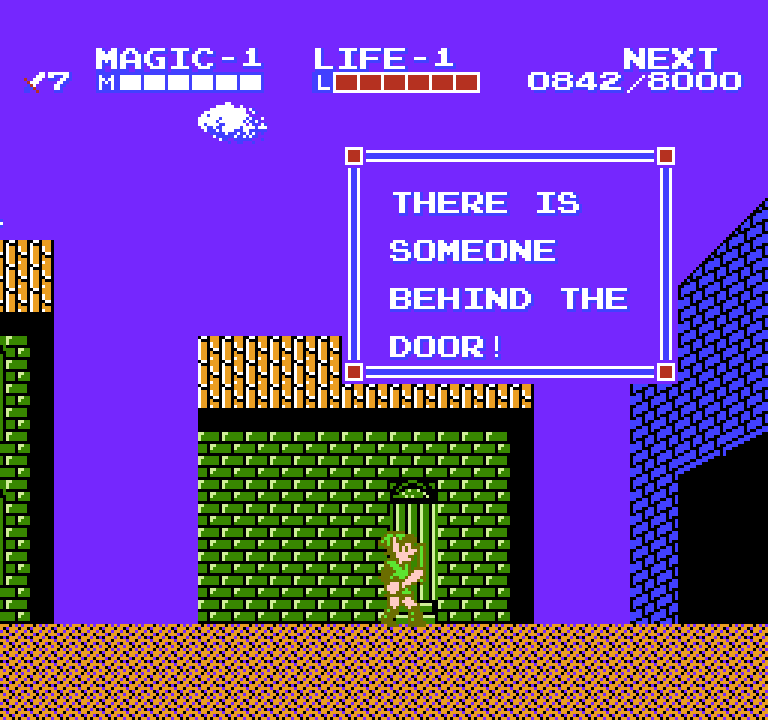

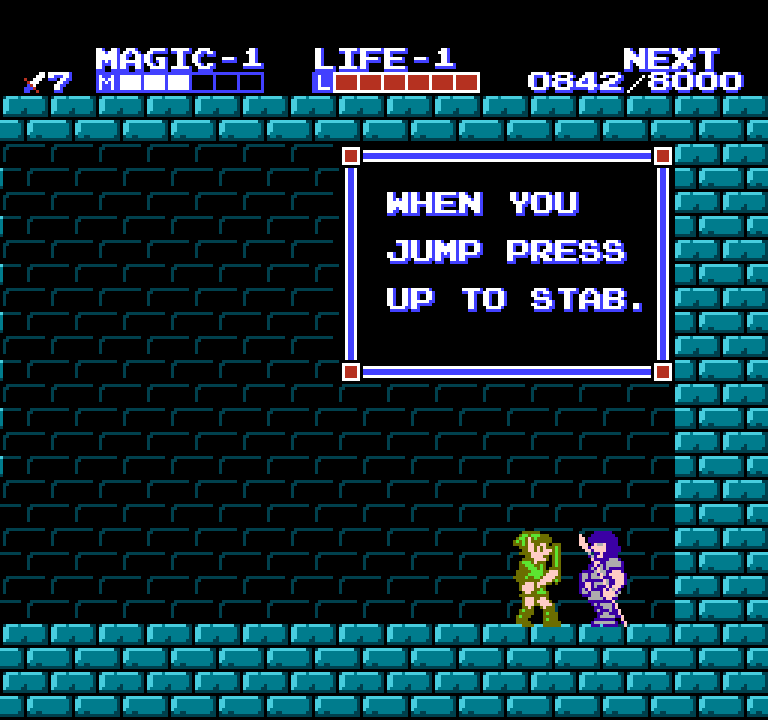

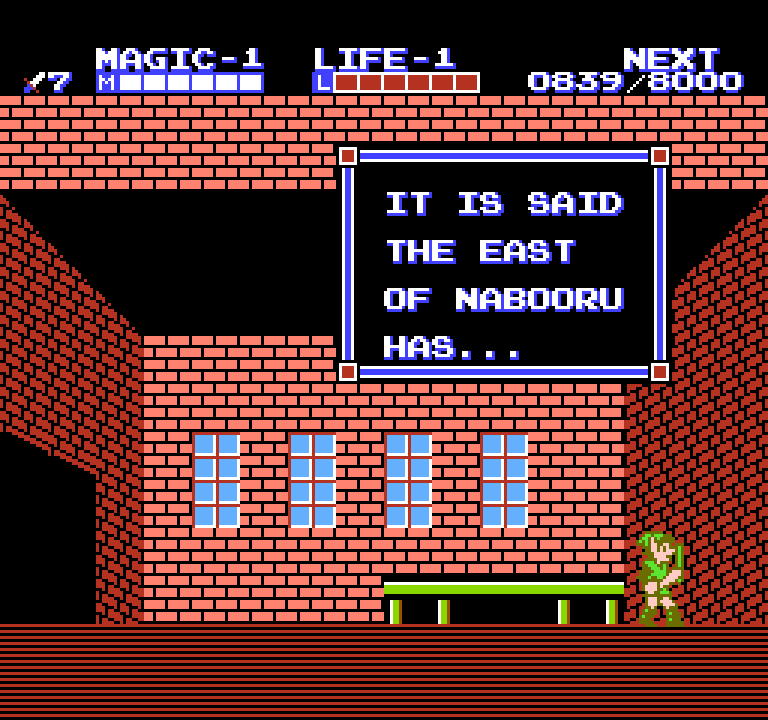

At first, I thought every line of text in the game was included in this French translation booklet, but it turns out that that’s not the case. A bunch of lines were dropped or went missing:

We can see that the French translation booklet skips important and unimportant text alike. Some of these lines are needed to progress the game, though, so I wonder if they caused any problems for players who didn’t have outside resources like gaming magazines.

Translation Comparisons

I consulted two native French speakers about this Zelda II translation booklet. Below are some of the more interesting translations they pointed out, along with notes they included.

I’ve also included a couple notes of my own, and have highlighted some of my favorite differences in a tomato-ish color.

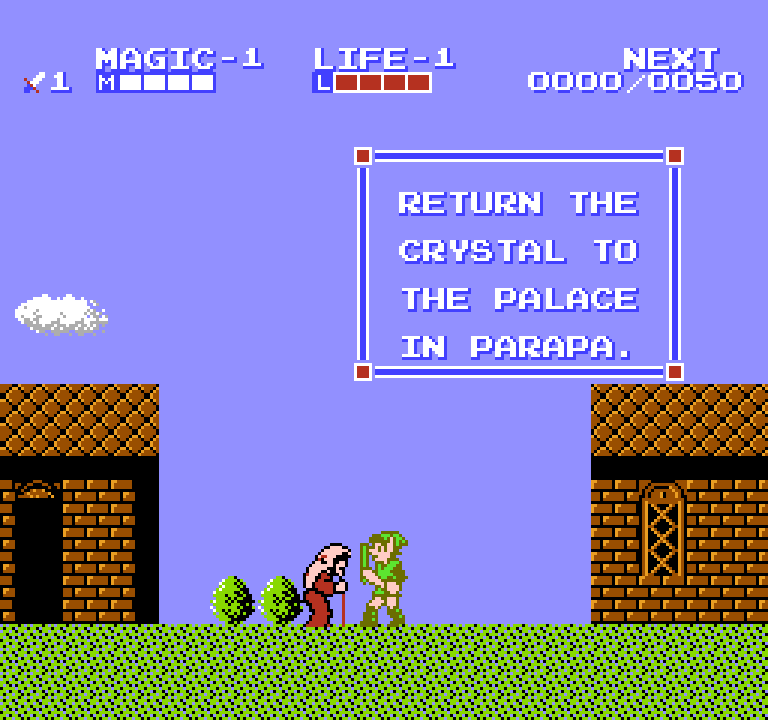

Return the crystal to the palace in Parapa.French: Rapporte le Cristal au Palais de Parapa. Meaning: Return the Crystal to the Palace of Parapa. Note: Oddly has some extra capital letters. Mato Note: This is a common thing throughout the booklet’s translation, so we’ll skip most of the other instances of this happening. |

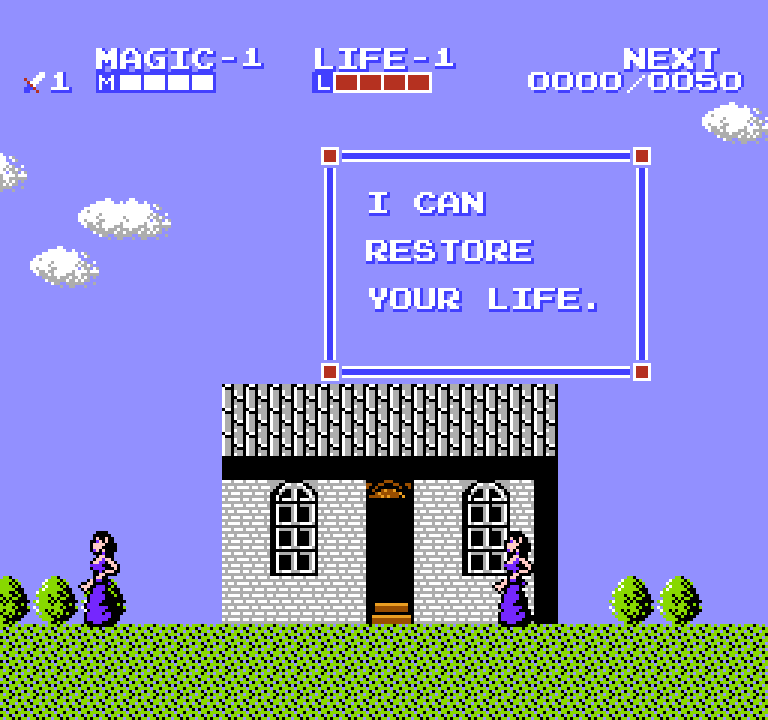

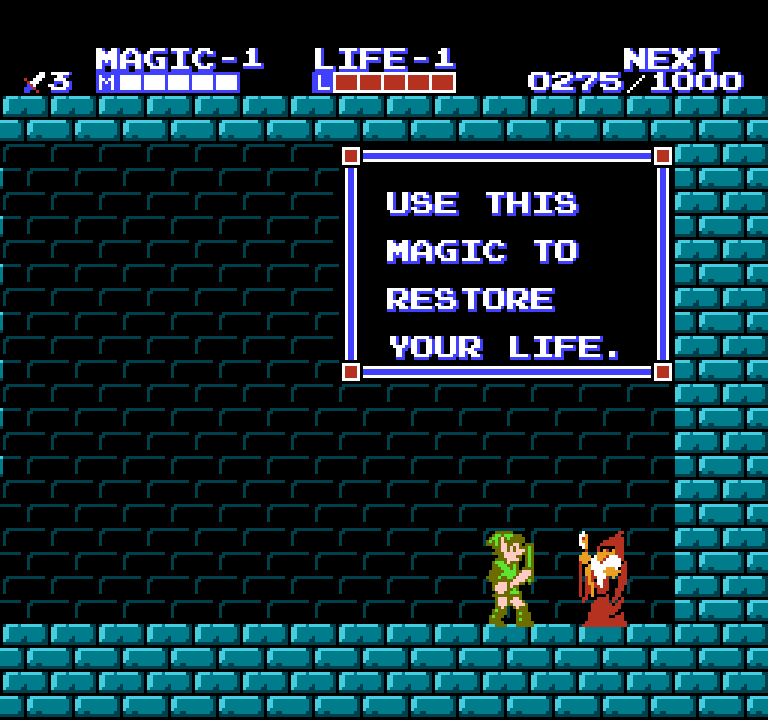

I can restore your life.French: Je peux te redonner la vie. Meaning: I can give back life. Note: The French translation has more of a sense of giving back a life rather than talking about restoring life points. |

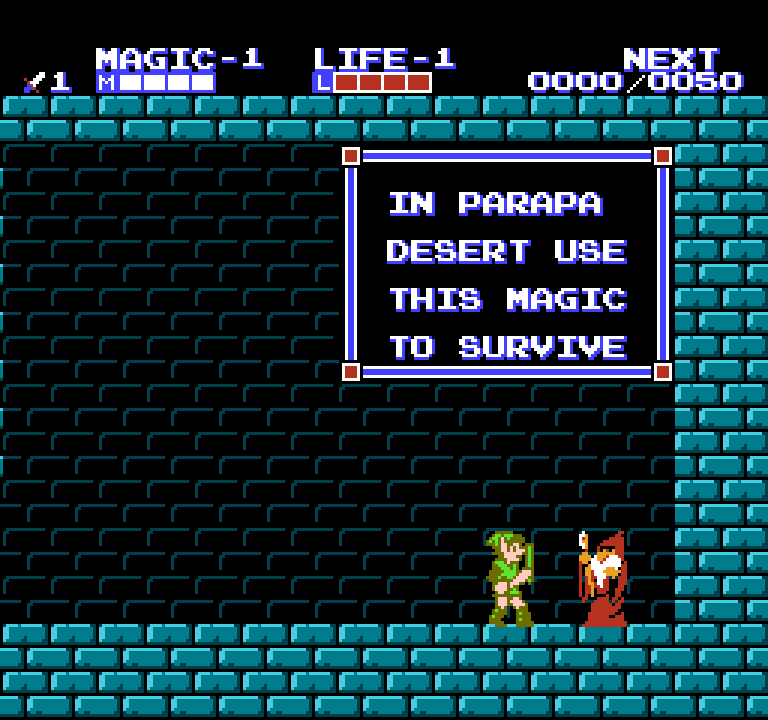

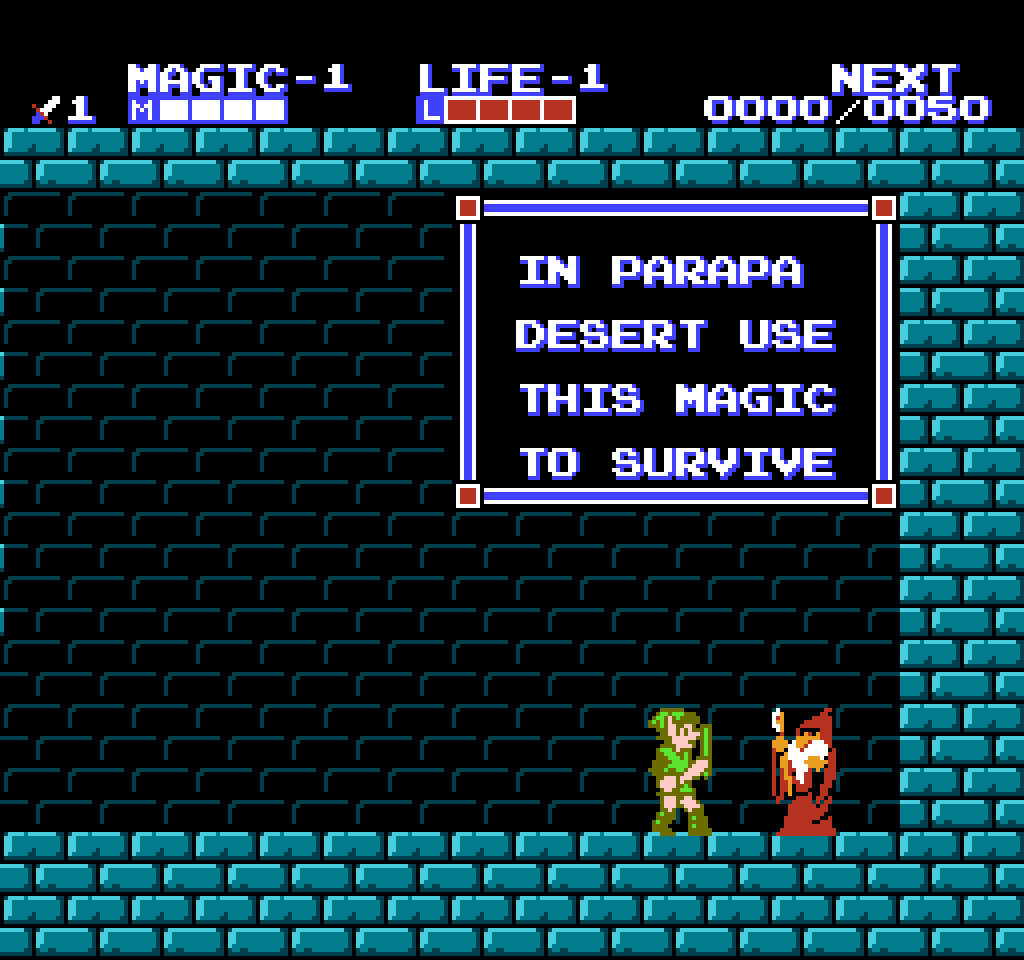

In Parapa Desert use this magic to surviveFrench: Dans le Désert de Parapa utilise le pouvoir magique pour survivre. Meaning: In the Desert of Parapa use the magic power to survive. Note: The original line talks about using this magic to survive but the French one talks about magic in general. |

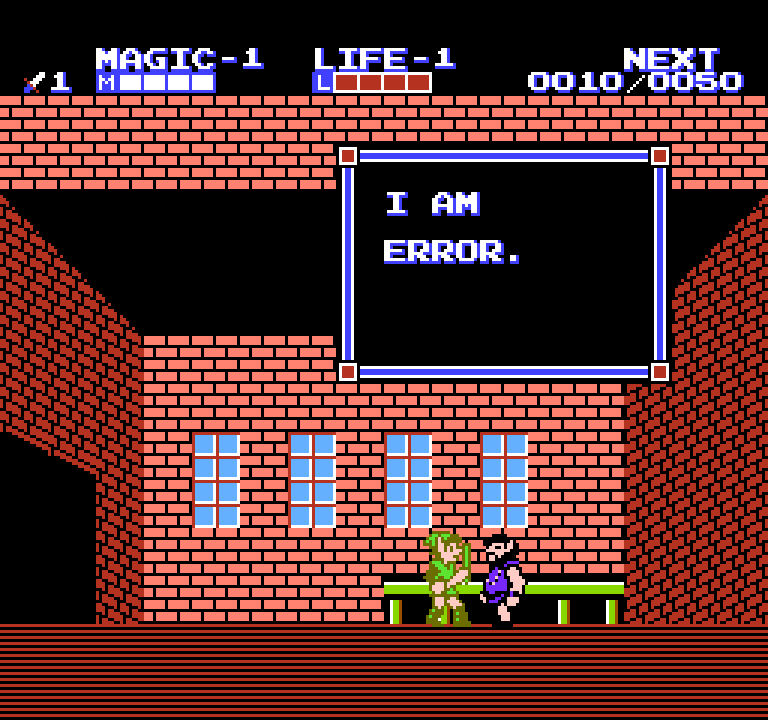

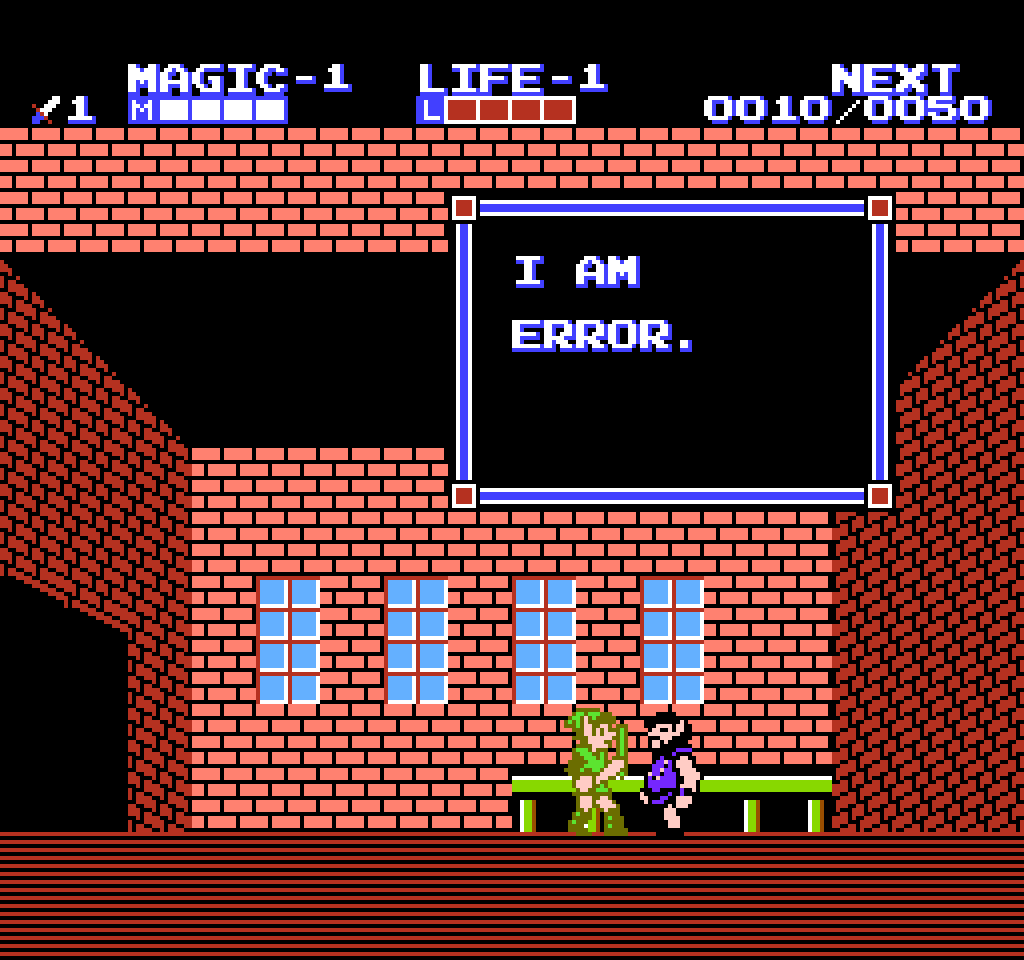

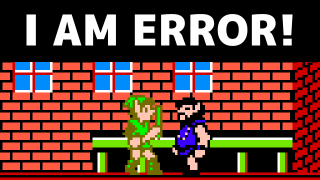

I am Error.French: Je suis Error. Meaning: I am Error. Note: The French kept the English name as-is and did not use “Erreur”. |

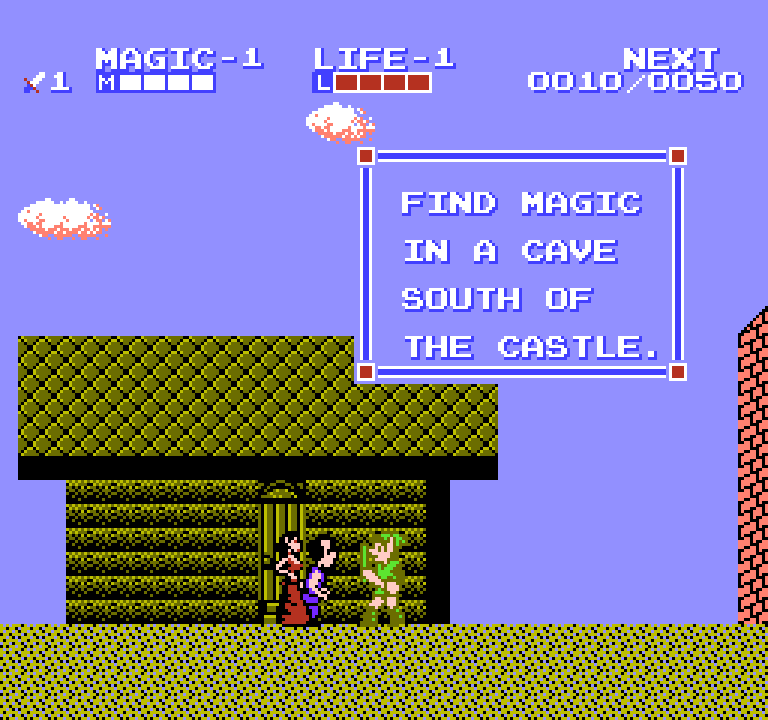

Find magic in a cave south of the castle.French: Trouve l’Instrument magique dans la cave sud du château. Meaning: Find the Magic instrument in the southern cave of the castle. Note: The French line talks about a “magic instrument” instead of just magic. Also, since it’s the cave south of the castle, it should be au sud du château. Written as-is, it seems like the castle has multiple caves and you should go to the south one. |

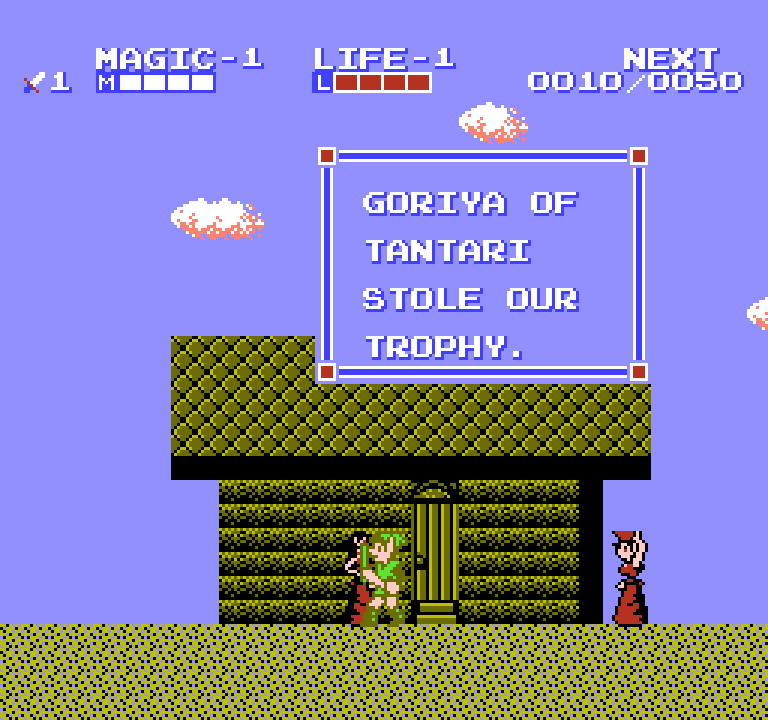

Goriya of Tantari stole our trophy.French: Les Goriya de Tantari ont volé notre Trophée. Meaning: The Goriya of Tantari have stolen our Trophy. Note: In French, they specify that “Goriya” is plural here. |

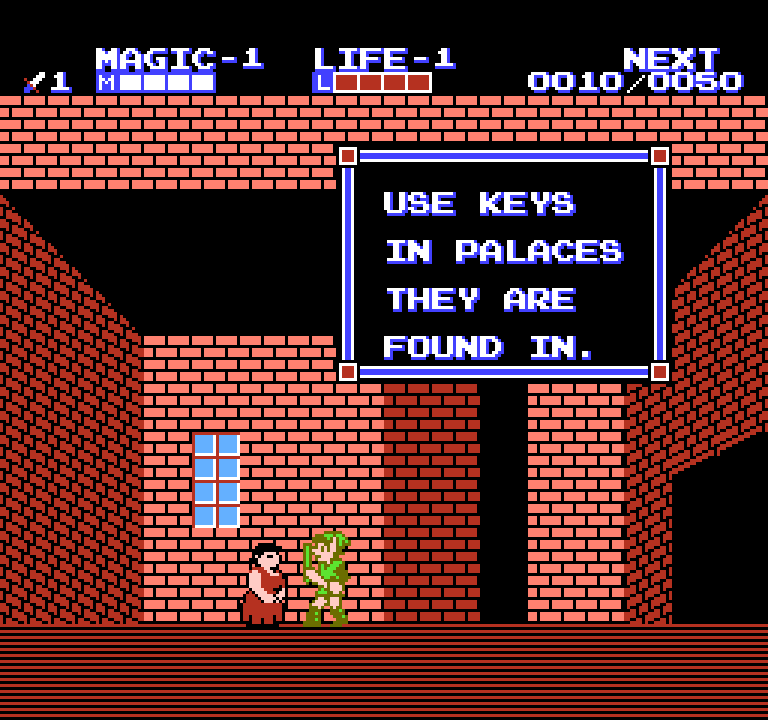

Use keys in palaces they are found in.French: Utilise les clés dans les Palais. Elles s’y Trouvent. Meaning: Use the keys in Palaces. They are Found in. Note: The English transcription in the French booklet mistakenly breaks this up into two sentences: “Use the Keys in Palaces. They are found in.” The French translation is word-for-word the same. |

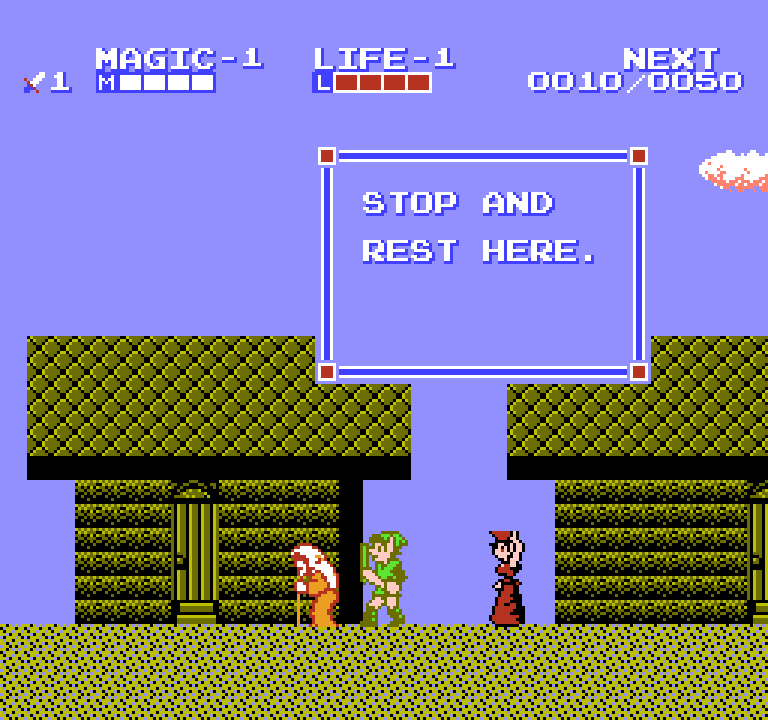

Stop and rest here.French: Arrête-toi et repose-toi ici. Meaning: Stop yourself and rest yourself here. Note: More emphasis on referring to “you” than in the English version. |

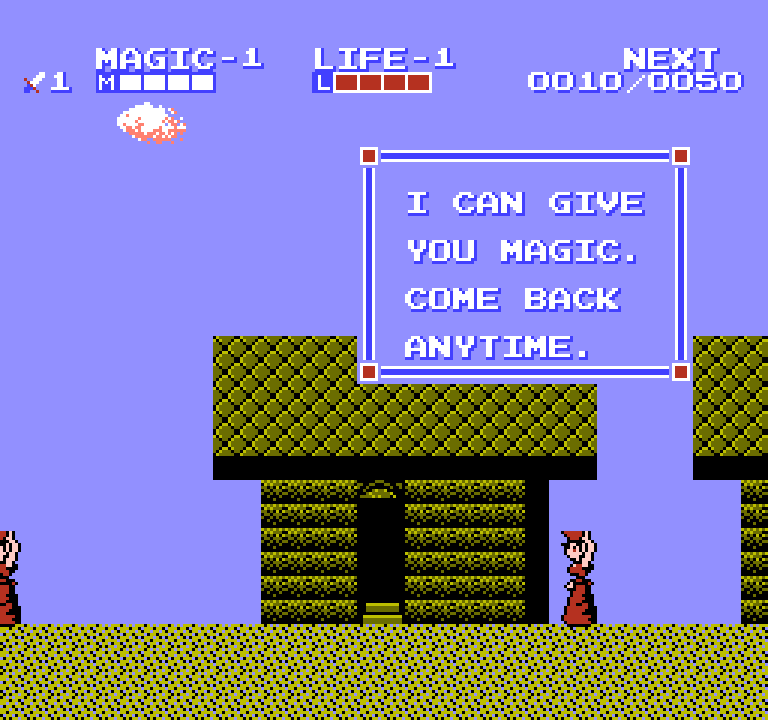

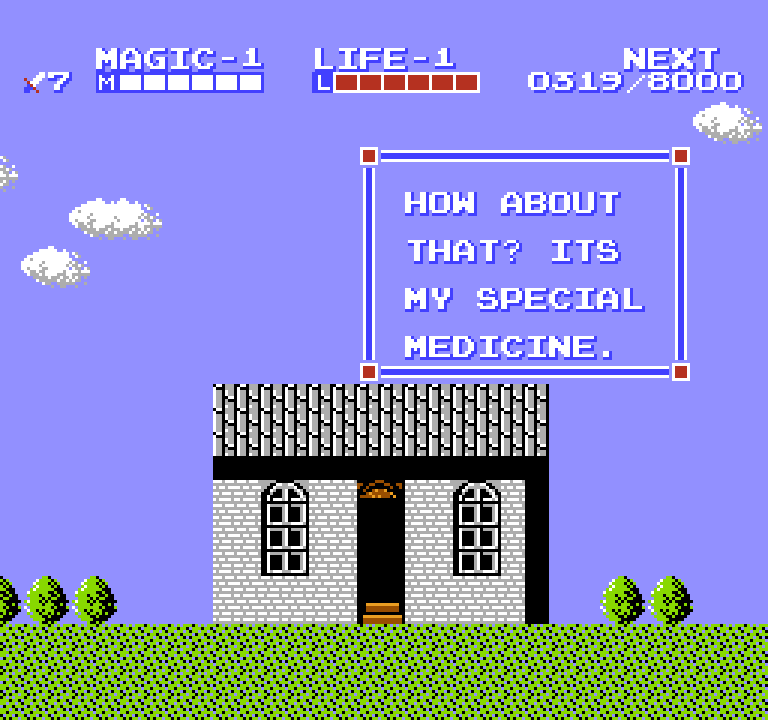

I can give you magic. Come back anytime.French: Je peux te donner de la potion magique. Reviens quand tu veux. Meaning: I can give you magic potion. Come back anytime you want. Note: The French line talks about a “magic potion” instead of just “magic”. |

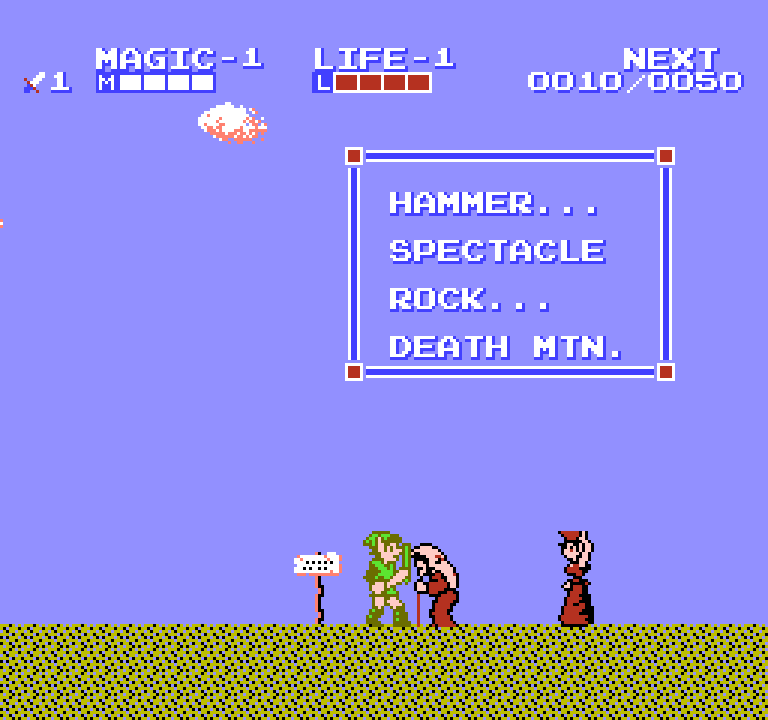

Hammer… Spectacle Rock… Death MTN.French: Marteau… Spectaculaire Roche… Montagne de la Mort. Meaning: Hammer… Spectacular Rock… Mountain of Death. Note: They didn’t translate location names for most of the game’s text, but here they changed “Spectacle Rock” to “Spectaculaire Roche”, which is wrong. |

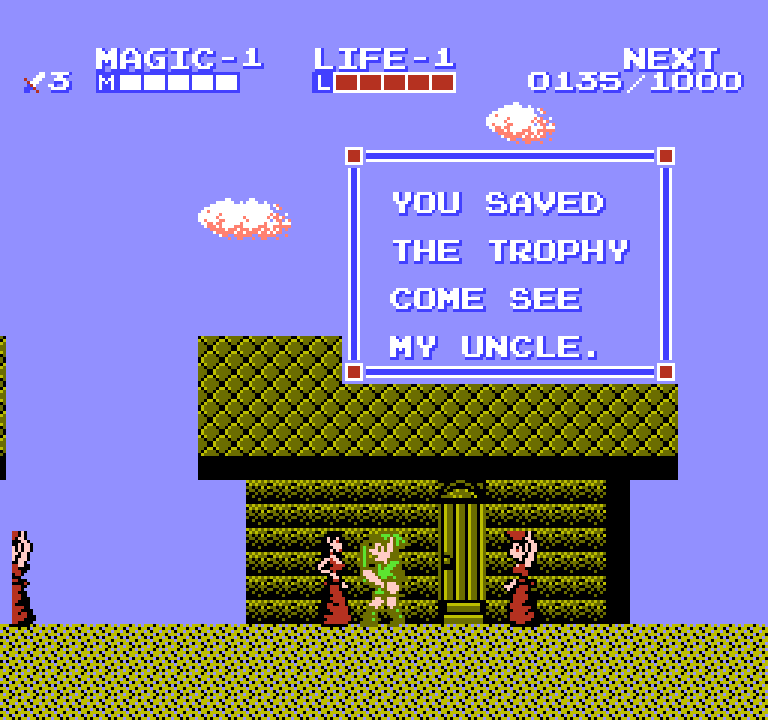

You saved the trophy come see my uncle.French: Tu as sauvé notre Trophée. Viens voir mon oncle. Meaning: You saved our Trophy. Come see my uncle. Note: The French translation uses two separate, logical sentences. |

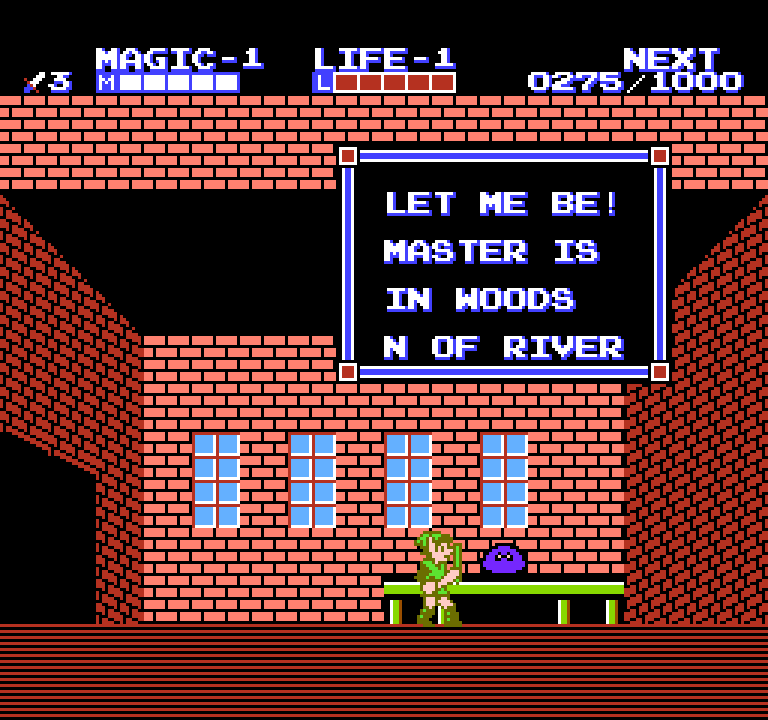

Let me be! Master is in woods N of river.French: Laisse-moi! Le Maître est dans les Bois et les Rivières. Meaning: Let me be! The Master is in the Woods and the Rivers. Note: They probably mistook the “woods n of river” as “woods and river”, so the French booklet got that instead of “north”. |

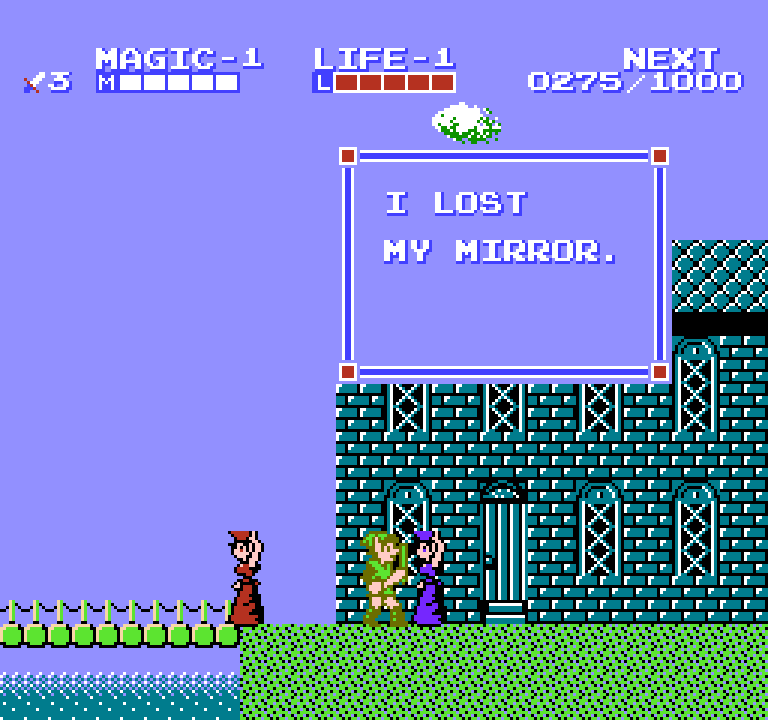

I lost my mirror.French: Trouve mon miroir. Meaning: Find my mirror. Note: The French booklet actually mistakenly lists the English line as “Find my Mirror”. |

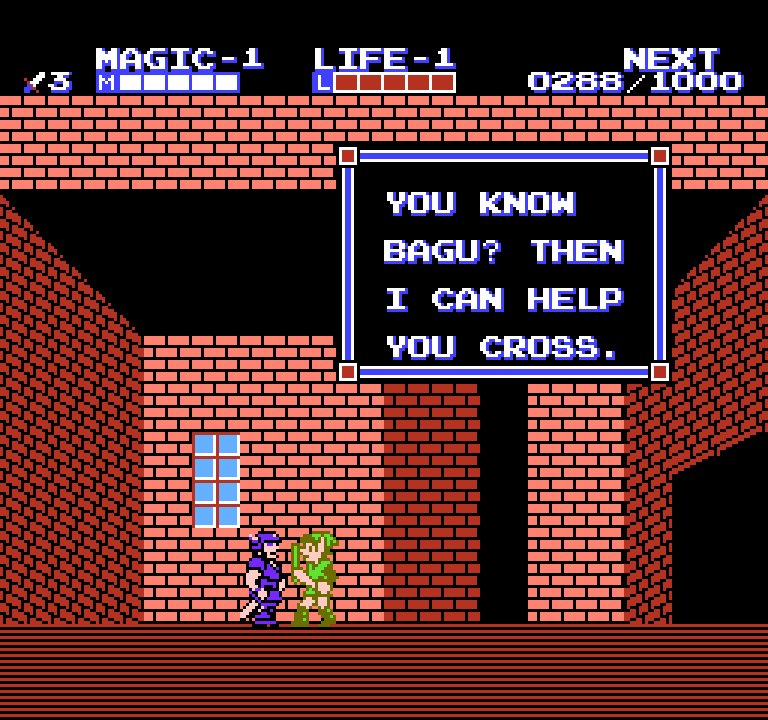

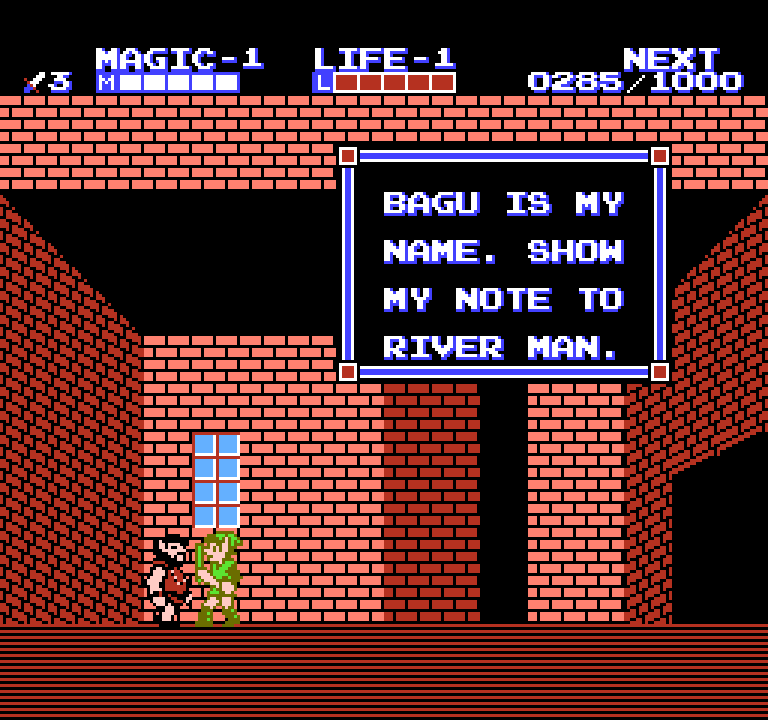

You know Bagu? Then I can help you cross.French: Connais-tu Bagu? Alors je peux t’aider à traverser. Meaning: Do you know Bagu? Then I can help you cross. Note: Connais-tu (“Do you know”) works, but Tu connais (“You know”) would’ve probably be closer to the English version, but I feel like since it was a booklet translation they used longer phrases that had more style than just the strict minimum like in the game. |

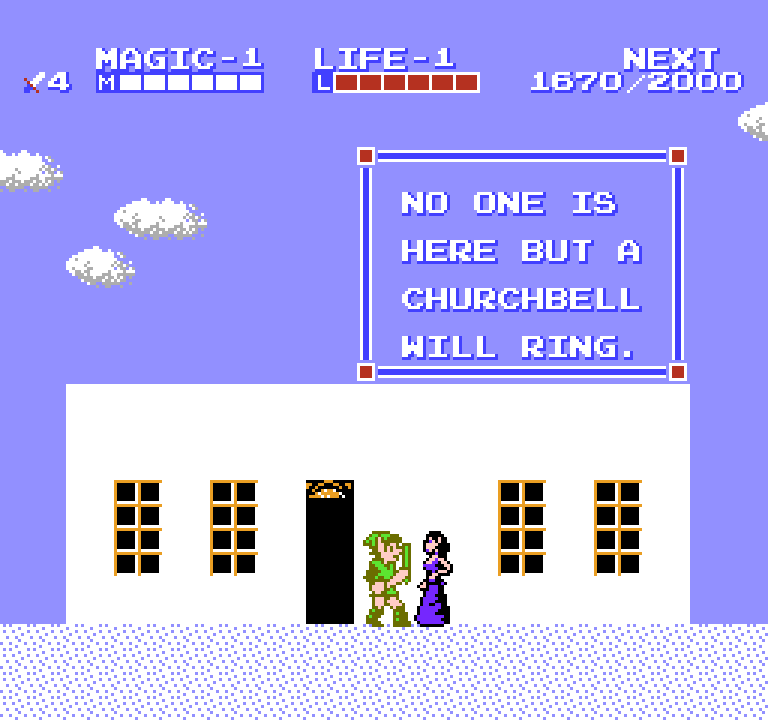

No one is here but a churchbell will ring.French: Il n’y a personne mais la cloche sonnera. Meaning: There is nobody but the bell will ring. Note: The French doesn’t point to as specific a location as the English version. |

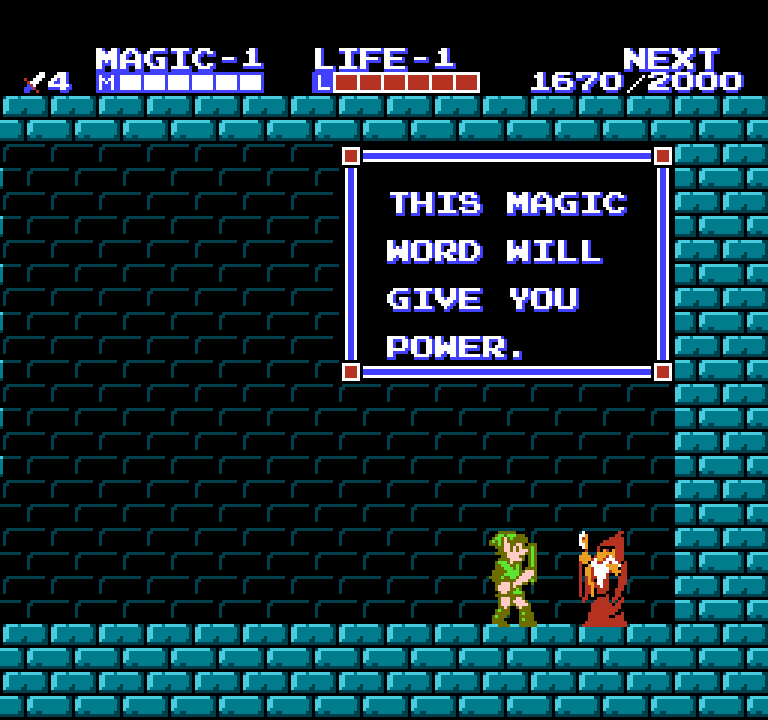

This magic word will give you power.French: Cette potion magique te donnera du pouvoir. Meaning: This magic potion will give you power. Note: The French booklet takes “word” out of the English line and instead talks about a “magic potion”. They probably changed “word” to “potion” because mot (“word”) wouldn’t make sense. |

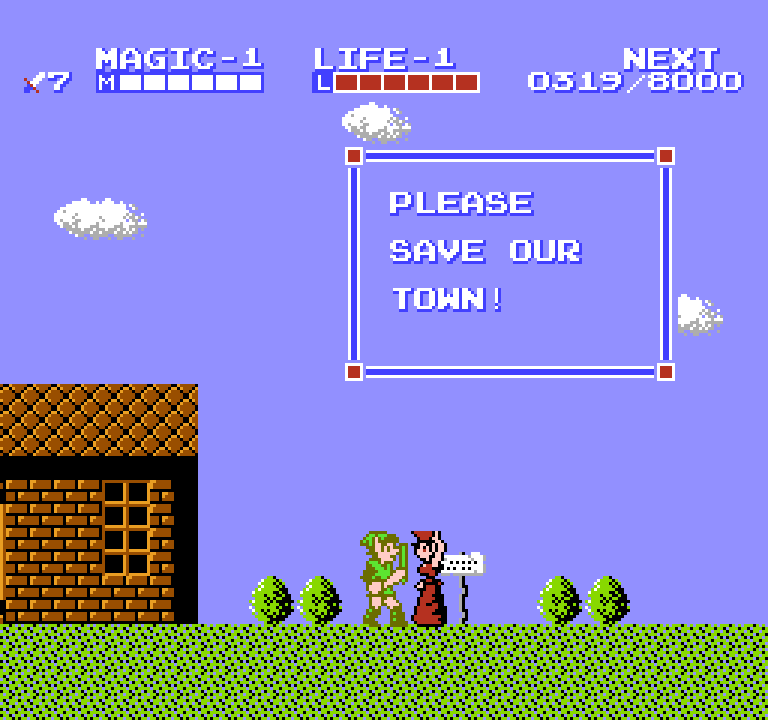

Please save our town!French: Je t’en prie, sauve notre ville. Meaning: Please, save our town. Note: The French line is written as two phrases instead of one. |

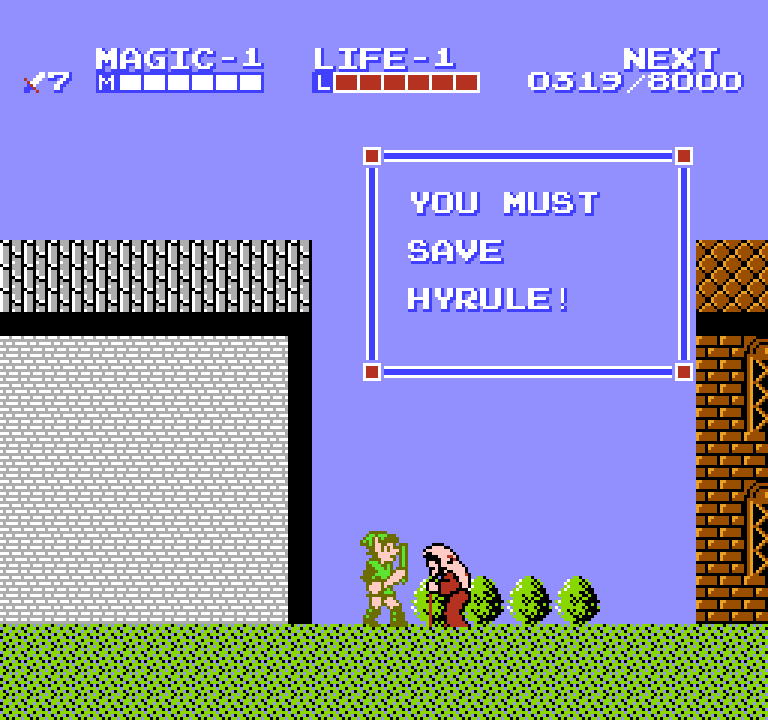

You must save Hyrule!French: Tu dois sauver HYRULE. Meaning: You must save HYRULE. Note: Why is “Hyrule” in all-caps? |

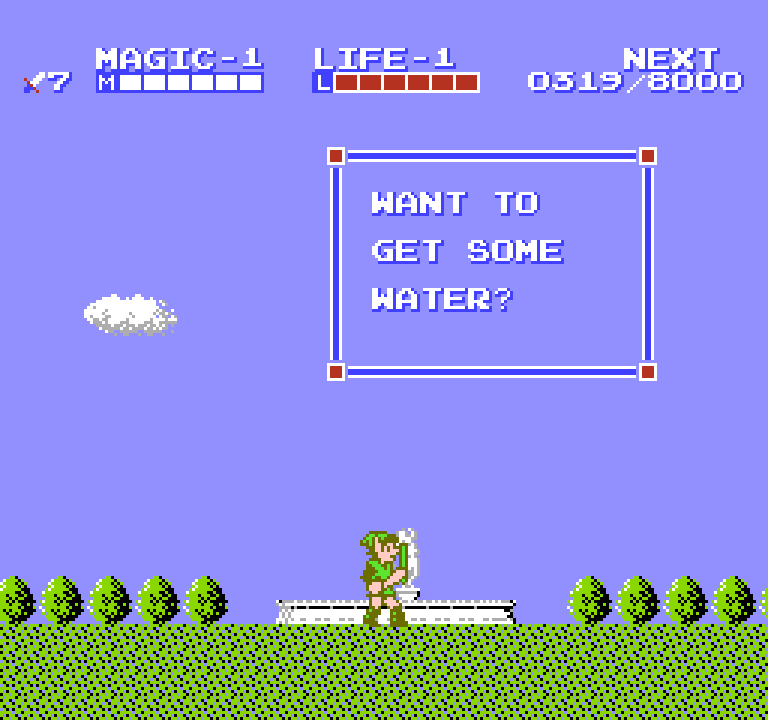

Want to get some water?French: Veux-tu aller chercher de l’eau. Meaning: Can you go find some water. Note: The question mark is missing in French. Mato Note: Also, this text appears when you check a fountain in town, not when you talk to a person. |

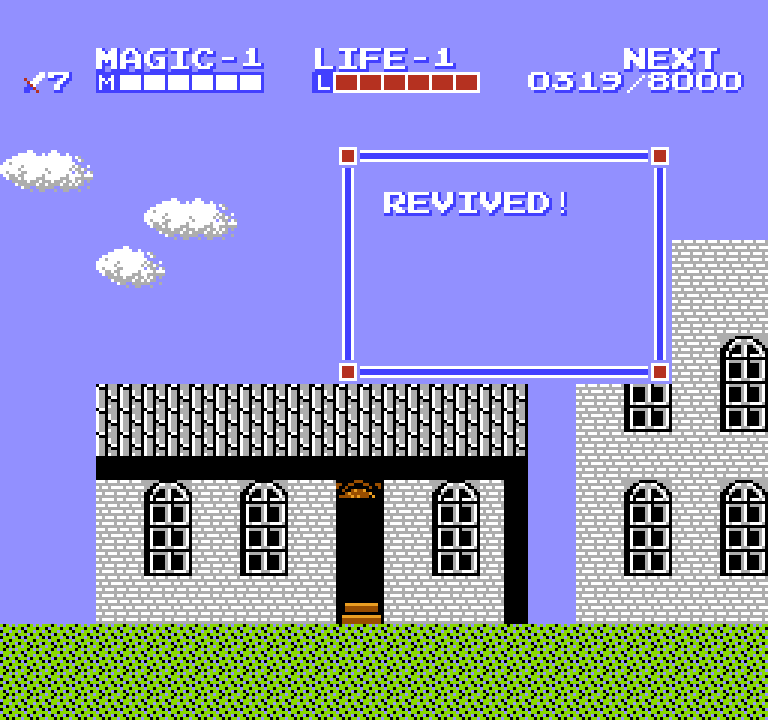

Revived!French: Régénéré. Meaning: Regenerated. Note: “Revived” sounds more like coming back to life while “Régénéré” is more about recovery. |

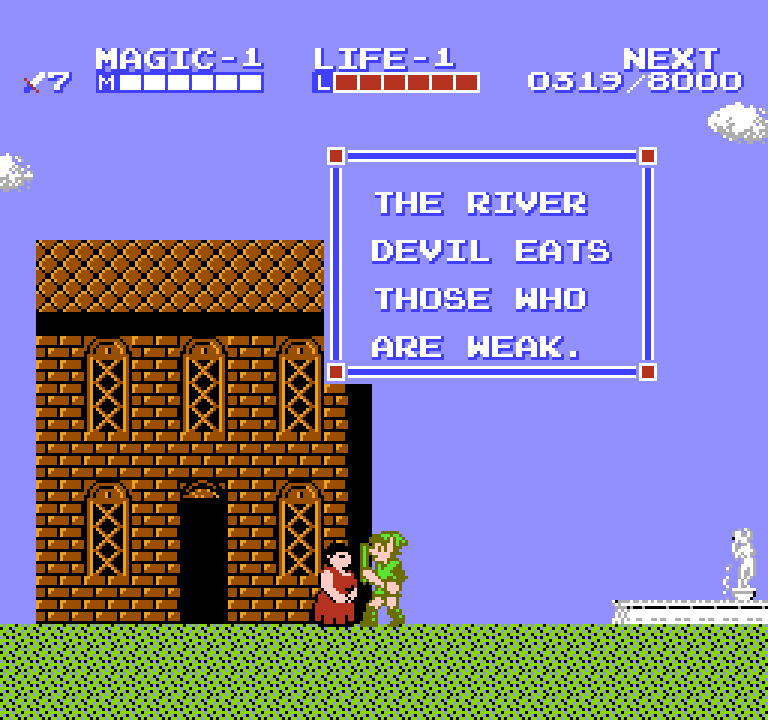

The River Devil eats those who are weak.French: Le Démon de la Rivière dévore ceux qui sont faibles. Meaning: The Demon of the River devours those who are weak. Note: They used “demon” in French instead of diable (“Devil”). |

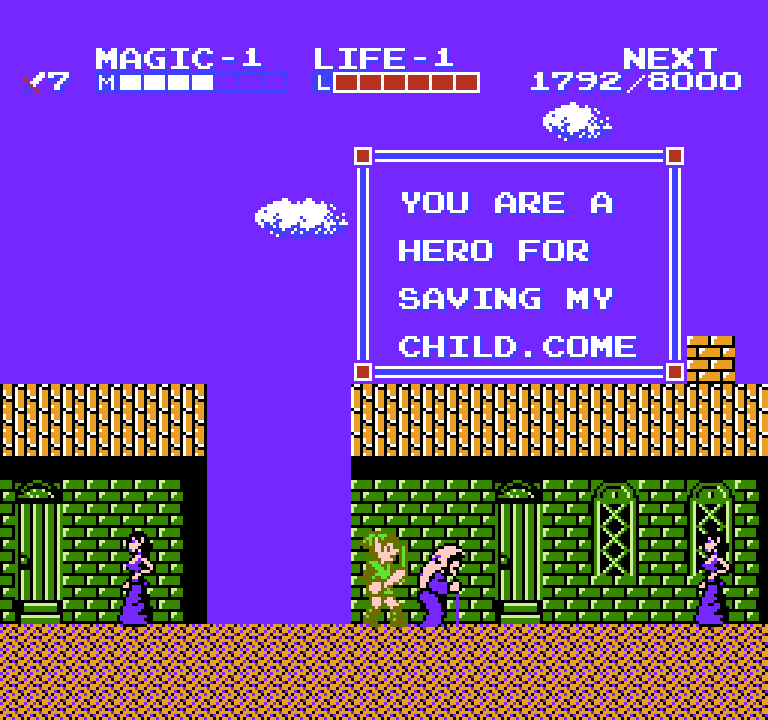

You are a hero for saving my child. ComeFrench: Tu es un Héros d’avoir sauvé mon enfant. Viens. Meaning: You are a Hero to have saved my child. Come. Note: The French sentence is strange as it uses d’ which is the preposition de but used before a word that begins with a vowel, which does not give a sense of cause and effect. |

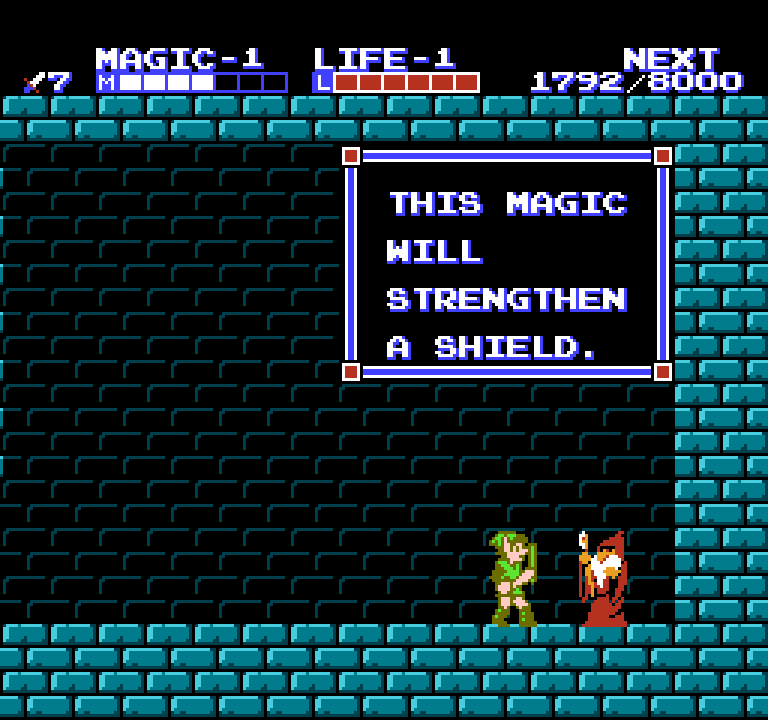

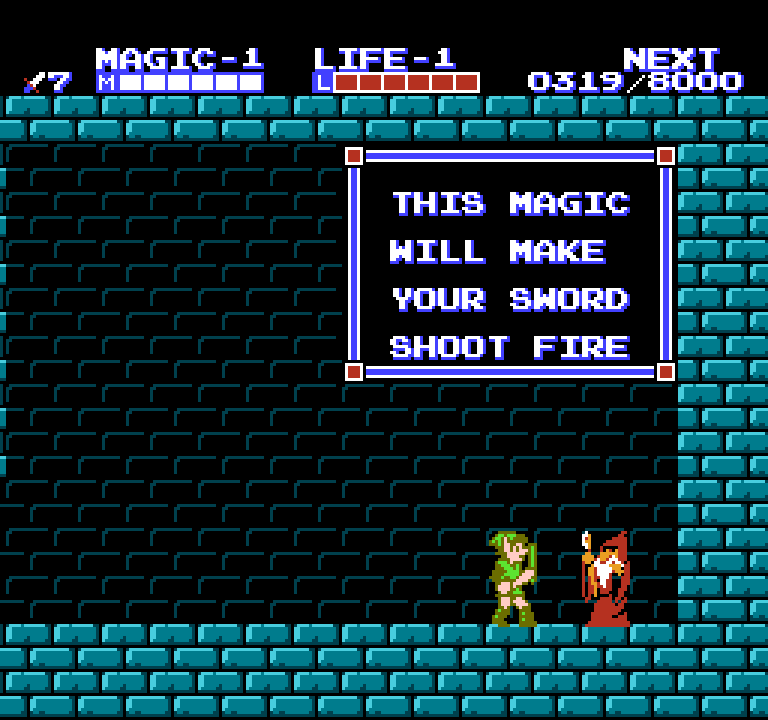

This magic will strengthen a shield.French: Ce pouvoir magique accentuera l’effet. Meaning: This magic power will strengthen effect. Note: The French translation doesn’t talk about a shield at all. |

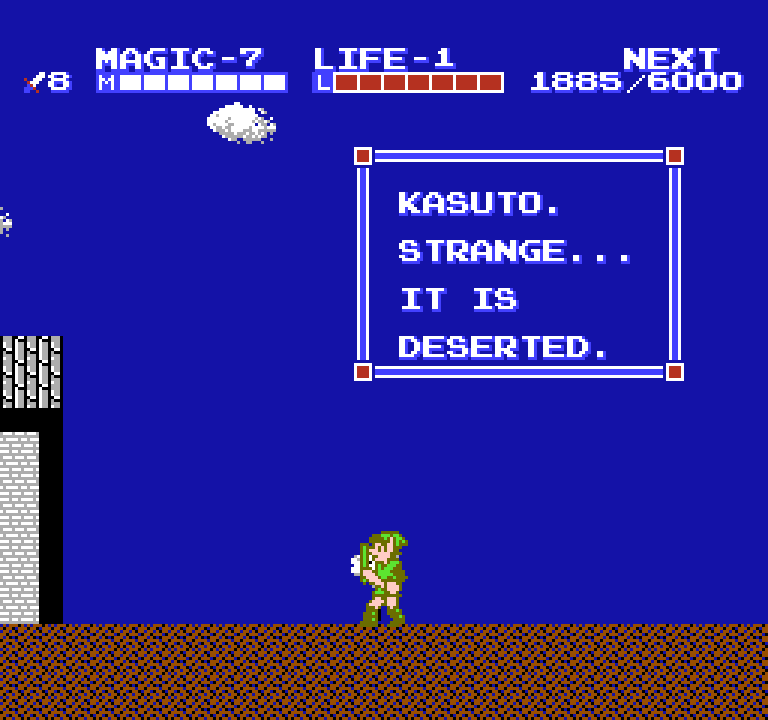

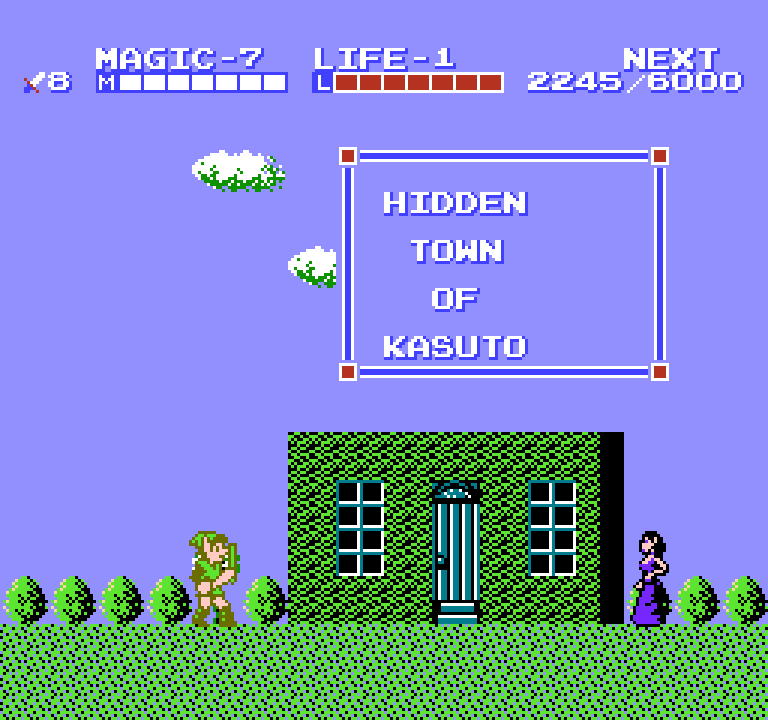

Kasuto. Strange… it is deserted.French: Kasuto Strange est un désert. Meaning: Kasuto Strange is a desert. Note: This is translated as if “Kasuto Strange” is the name of a desert. |

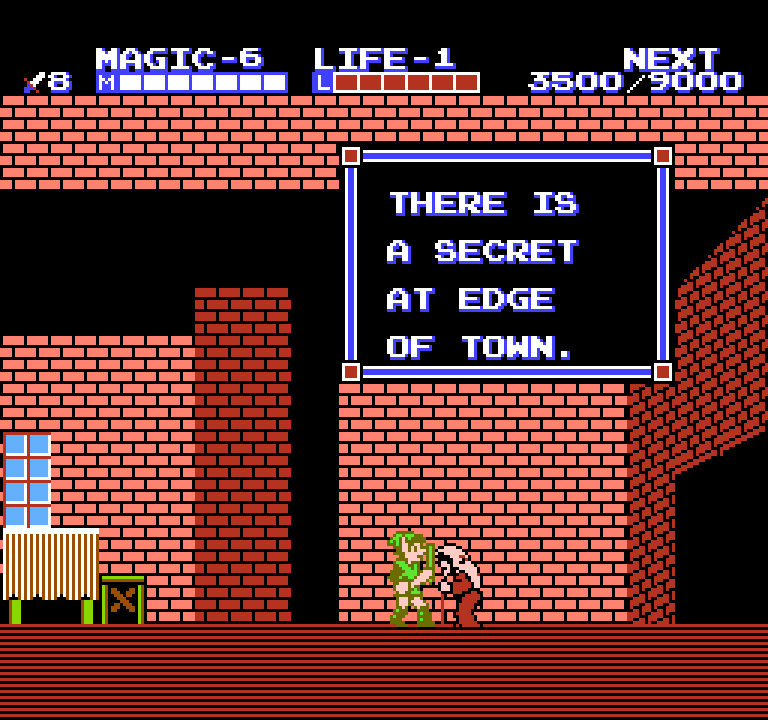

There is a secret at edge of town.French: Il y a un secret à la sortie de la ville. Meaning: There is a secret at the exit of the town. Mato Note: In the game, the secret is actually at an edge of the town that’s a dead-end and not an exit. |

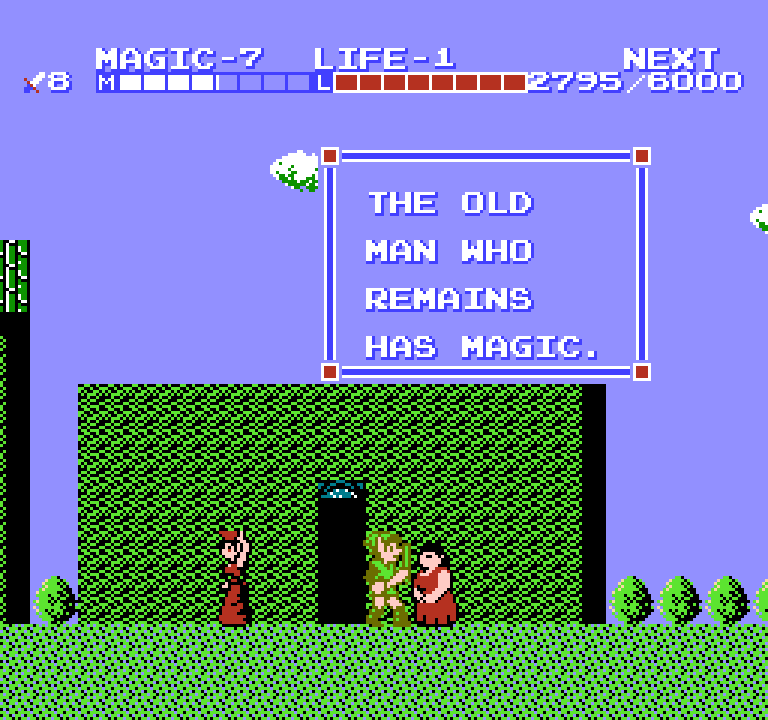

The old man who remains has magic.French: Il reste un Vieil Homme qui a le pouvoir magique. Meaning: There remains an Old Man who has the magic power. Note: The French line changes the sentence structure and mentions a “magic power” instead of “magic”. |

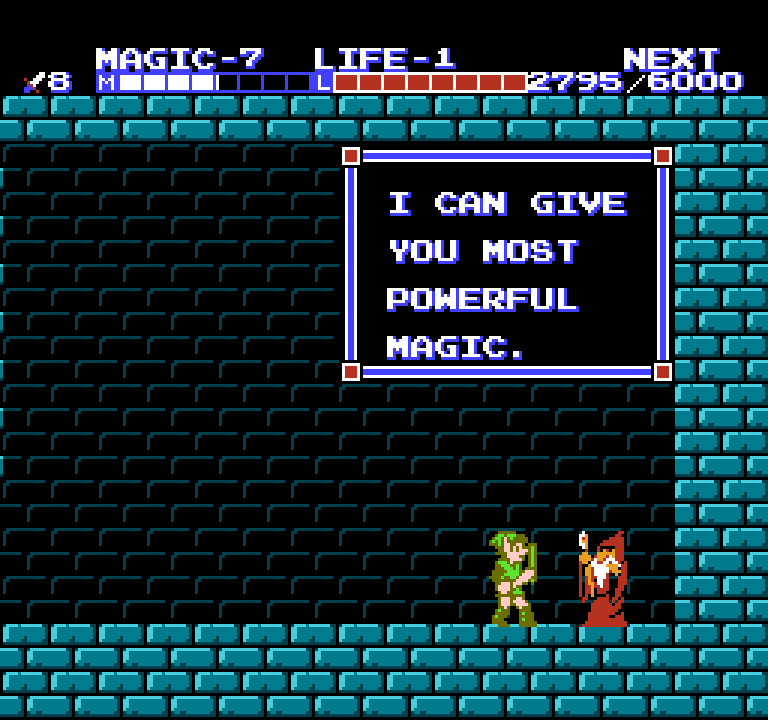

I can give you most powerful magic.French: Je peux te donner plus de pouvoir. Meaning: I can give you more power. |

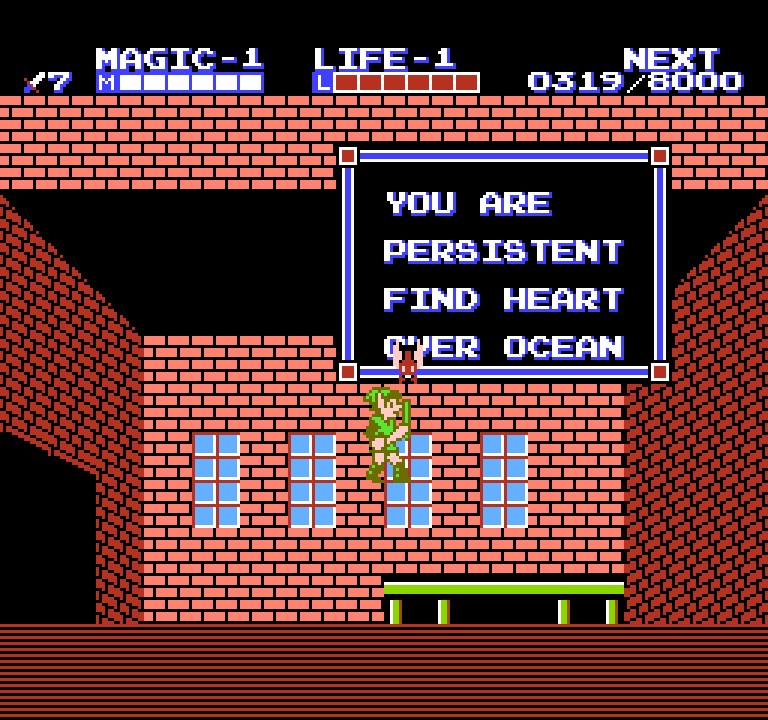

You are persistent find heart over oceanFrench: Tu persistes. Trouve le Cœur au-dessus de l’Océan. Meaning: You are persistent. Find the Heart above the Ocean. Note: The French line breaks this into two logical sentences. |

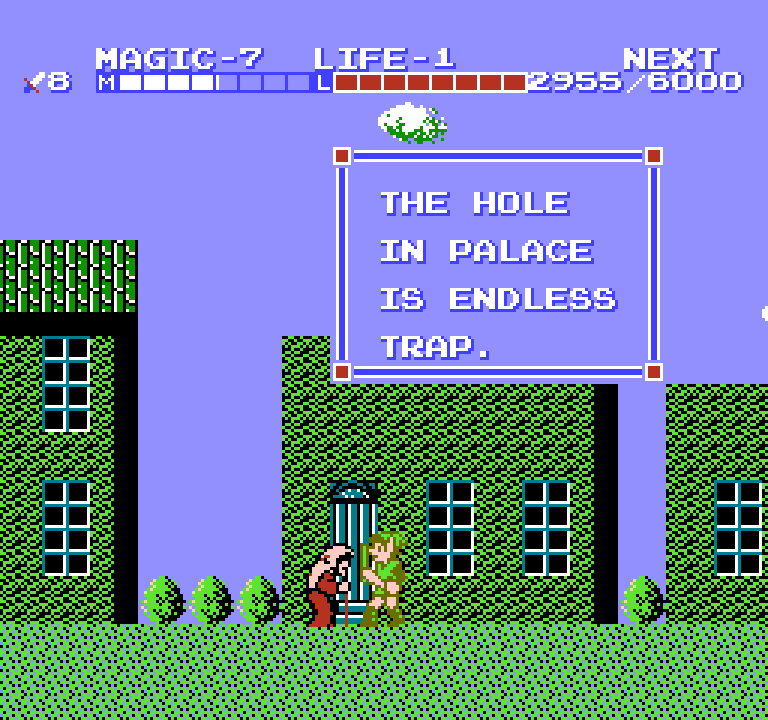

The hole in palace is endless trap.French: Le trou dans le Palais est un puits sans fond. Meaning: The hole in the Palace is a bottomless pit. Note: They use “pit” instead of “trap” in French. They could’ve gone with un piêge sans fond instead. |

East of Triple Eye Rock at seashore.French: A l’est de Triple Eye. Un rocher au bord de la mer. Meaning: To the east of Triple Eye. A rock at seashore. Note: The French writes this as two sentences. |

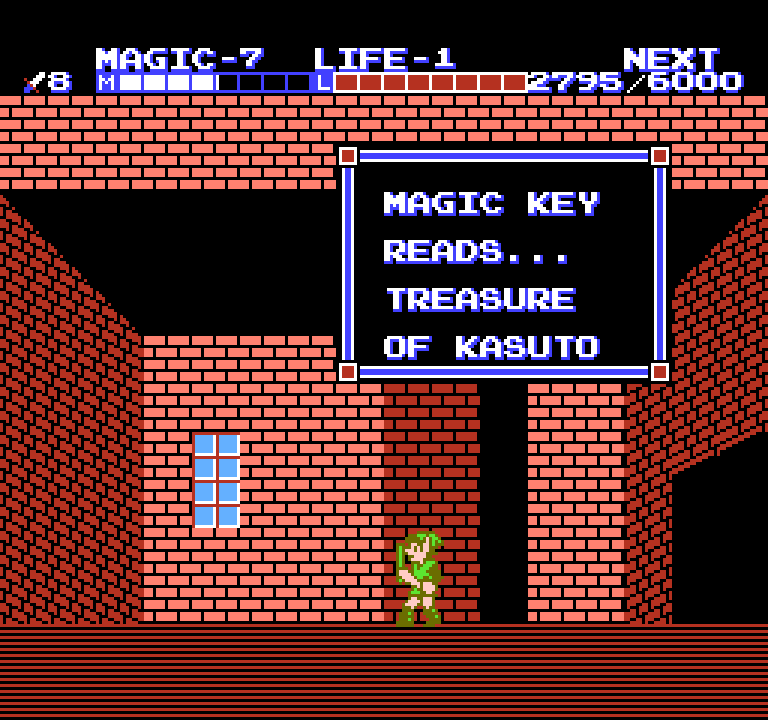

Magic key reads… Treasure of KasutoFrench: Clé Magique. Trésor de Kasuto. Meaning: Magic Key. Treasure of Kasuto. Mato Note: The French clearly turns this line into two distinct sentences. |

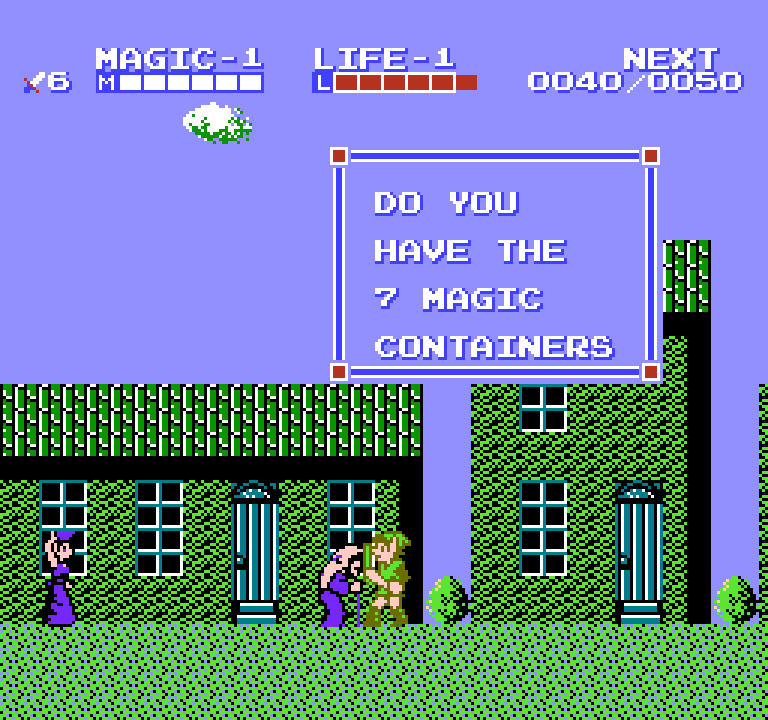

Do you have the 7 magic containersFrench: As-tu les 7 containers magiques? Meaning: Do you have the 7 magic containers? Note: “Containers” is left as-is in the French sentence instead of the French word conteneurs. Conteneurs here would feel weird since I read that more like “shipping containers”, I’d rather use Contenants (“container”). Maybe contenant de magie (“magic container”) would work better in this case. |

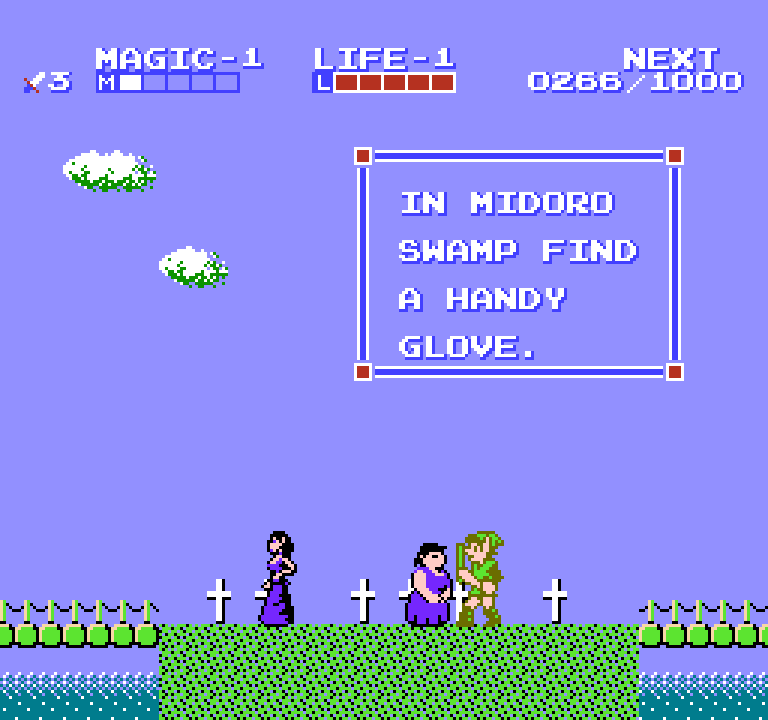

In Midoro Swamp find a handy glove.French: Dans les marécages de Midoro trouve un Gant de Feu ou un Gant Magique. Meaning: In Midoro Swamp find a Fire Glove or a Magic Glove. Note: Oddly talks about two gloves. “Handy Glove” would probably translate to Gant Utile (“Useful Glove”) so I guess they had to give it another name. Also, it’s weird that they went with “Fire”. While I could see “Magic Glove” working, “Fire” doesn’t make much sense. |

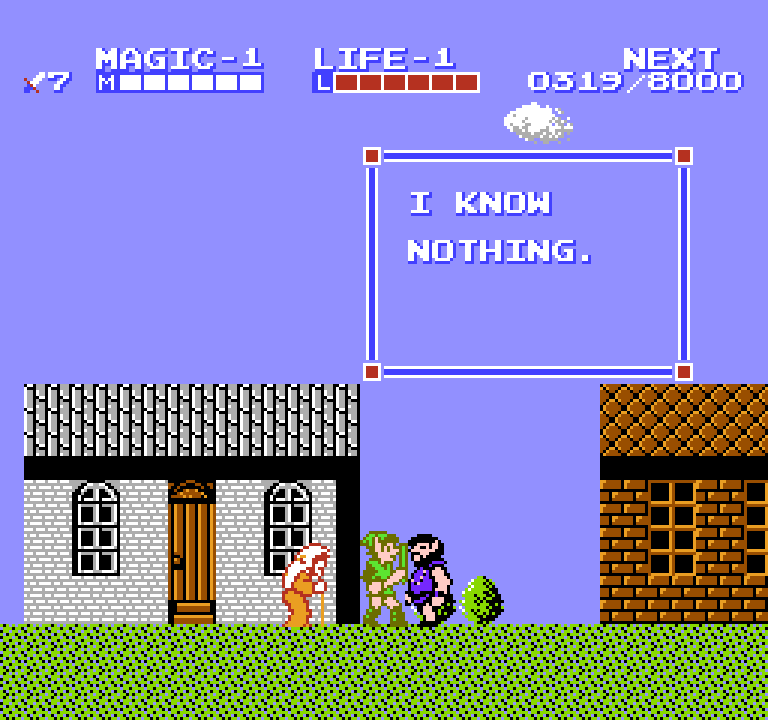

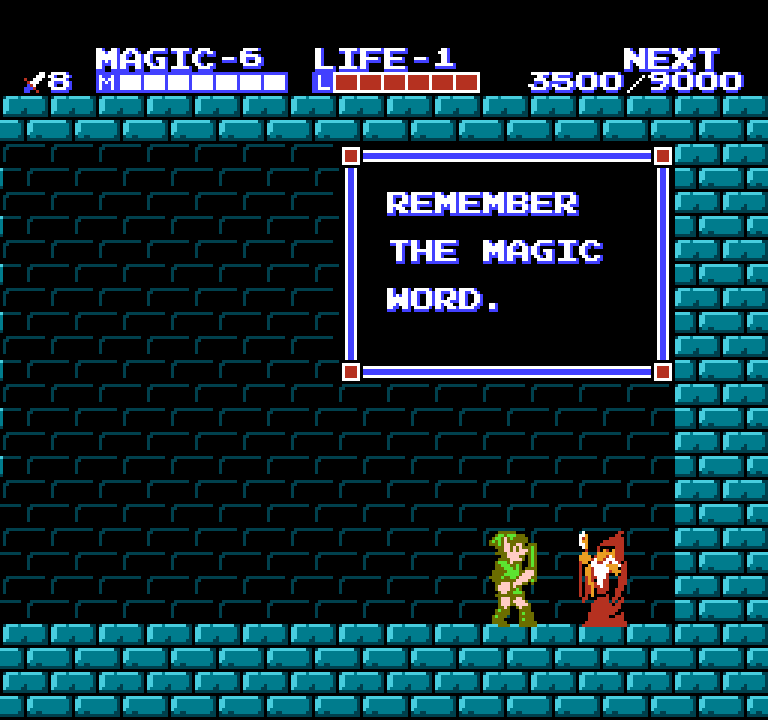

I know nothing.French: Désolé, je ne sais rien. Meaning: Sorry, I know nothing. Note: This line was given an added apology. |

Remember the magic word.French: Souviens-toi de ces paroles. Meaning: Remember these words. Note: This translation doesn’t mention magic. Like with earlier lines, they didn’t want to translate “magic word” into mot magique. |

As we can see, the official Zelda II French translation booklet has a bunch of minor translation issues and technicalities that don’t matter too much, but the booklet also contains a number of genuine mistranslations and baffling choices. Surprisingly though, some of the French lines seem slightly better than the English text. But maybe that’s just because the English text had to be crammed into tiny text boxes.

Final Thoughts

All in all, I really enjoyed looking at this little-known translation of Zelda II and getting a peek at the quality of early European console game translations. Later Zelda games started receiving fully translated releases throughout Europe, so this booklet offers a neat look at video game translation history.

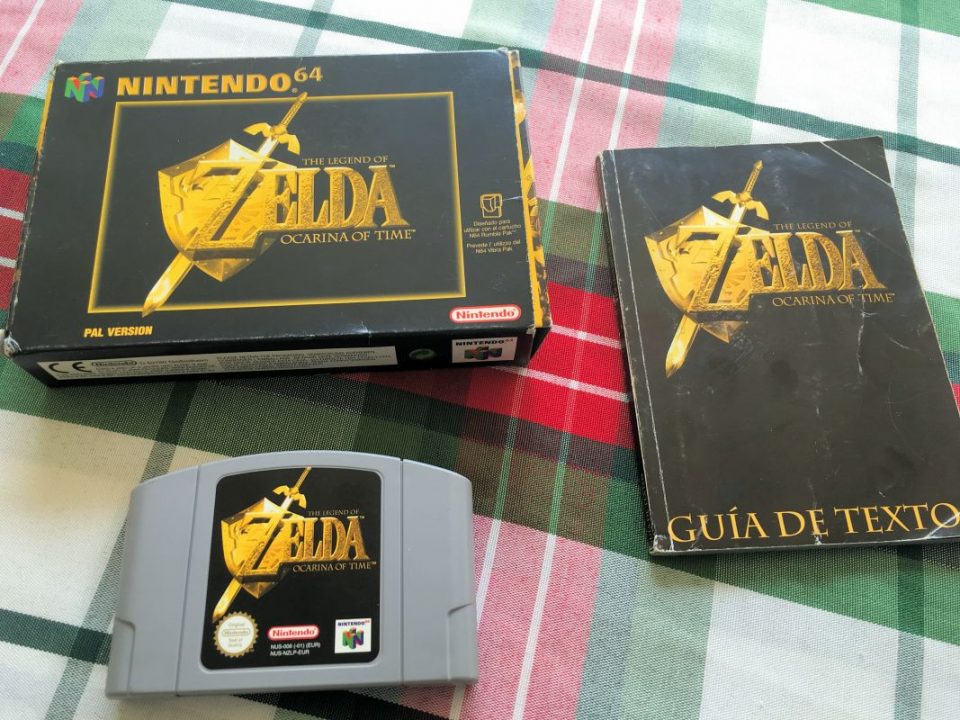

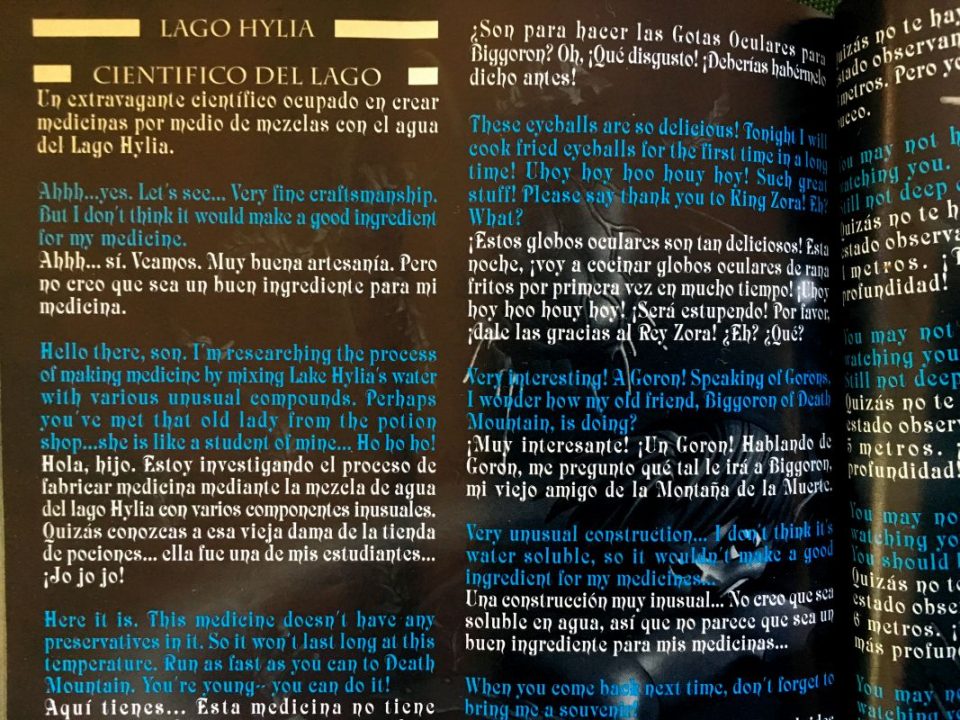

I don’t know how common this “translation booklet” thing was with console games back in the day, but when I asked on social media it sounded like most of my followers had never encountered it. I do know that it happened at least one other time, though, with Spain’s version of The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time:

Have you encountered any translation booklets in any other console games? If so, let me know in the comments!

Anyway, this was a fun little journey through an unusual Nintendo translation. Here’s hoping it’s the first of many more!

If you liked this look at Zelda II, you might like my book about the Japanese and English versions of Zelda 1. Or, if you're more of a Zelda II person, here are some other articles I've written about the second game!

There are a lot of errors even in their transcriptions of the English text, so they’re often translating English that’s even more wrong than the real text on screen.

I almost wonder if they were basing this on a beta version of the game or something. Some of their transcription errors seem a bit dramatic to be just that. I can maybe imagine someone careless turning “deserted” into “a desert,” but mistakenly transcribing “a shield” as “effect” seems quite peculiar.

Oh man, halfway through the article I was already planning on letting you know about the Spanish translation booklet from Ocarina of Time. I’d love to comb through that at some point!

This isn’t quite the trainwreck FFVII’s Japanese to poorly done English to even worse French is, but it is still noteworthy. I wonder why the French were so averse to using the term “magic word” anyway.

Because the magic world is “please” or “thank you”

I don’t know if that expression exists in other language, but when an adult tell a French kid to “remember the magic world(s)”, that’s the intended message. You ask the child to be polite.

So that would give a rather different meaning to a French speaker, which probably explain why it was changed.

The expression is the same in English (“say the magic word” is asking a child to say “please”) but I guess the phrase “magic word” isn’t so culturally bound up in that idiom that it can’t be used for more literal meanings.

If I had to take a guess, French imported the idiomatic sense of the phrase from English. We came up with the saying in the first place because anyone familiar with stage magic would know about magic words such as “abracadabra” or “hocus pocus” and then applied it to children — on the notion that without saying the special incantation, nothing would happen.

I’m reminded of a joke in a Cbeebies programme (that I can’t remember the name of) about a couple of puppets that lived in a library, and there was a rotating cast of human guests. In one episode, the human tells the green girl puppet to say the magic words, so she starts saying the literal magic words that they say in every episode, but then the human interrupts and tells her that they meant “please” and “thank you”.

That sounds like The Story Makers to me.

Yes it was! Thanks!

I’ve never heard “mot magiques” in French in any other context, it’s true, but “formule magique” would have worked in the “abracadabra” sense.

I too thought it was odd because the idiom of “magic word” being “polite words” also exists in English. Either way I’m surprised it was changed to “magic potion” and not something meaning “magic spell”. (Apparently there’s “formule magique” but I’m not sure of how common the usage is.)

“Formule magique” would be the best way to translate “magic spell”. It’s commonly used in most media involving magic so I don’t understand why they didn’t use it in this case.

That there’s a French translation of Zelda II for France doesn’t surprise me all that much. The French government doesn’t look kindly upon colloquial use of English, especially if it’s in some sort of mass-distributed context they can control for (TV, comic books, newspapers, etc.). For example, the French word for computer – l’ordinateur – has a 100% French etymology where (as far as I know) most other languages adopt/modify the English word for computer. The main worry is that English would slowly displace French if nothing was done to stop it.

You DO realise that translating games into languages other than English or Japanese used to be common practise, right?

It certainly still is. To this day PC games are oddly released with EFIGS translations – you can see it as a goal in Kickstarter games like Cyan’s Firmament too.

I don’t understand why they do this instead of CJK, which would have a few billion speakers.

Off the top of my head, Pokemon games since Sun and Moon are in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean.

Regarding “ordinateur” vs. “computer,” the French are also avoiding a couple of vulgar syllables—if you pronounce it with a French accent, “computer” comes out something like “twat whore-r.”

By the way it’s a funny joke used in the first french version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the computer deep though (with a pun about deep throat (the pornographic movie and the FBI agent about watergate scandal), the translator choose to use an older way to say “ordinateur” in France “computer” (yes before in France we used “computer at the beginning) to make a pun : le super compute-1 (the fucking super asshole if you read it in french).

Actually basically all Germanic languages uses a more local word, sometimes in addition to, but often instead of, a version of “computer”. Usually meaning something like “data machine”, “number prophetess” or a literal translation of “computer” (in the sense of something that does computations). Norwegian has datamaskin and data, Danish has regnemaskine and datamat, German has Rechner, Dutch and Afrikaans has rekenaar, Icelandic has tölva, Faroese has telda, Sweedish has dator and datamaskin, etc, etc. Even Scots use reckoner. Also Finnish uses the “data machine” set-up, tietokone, and Latvian uses dators, both taken from Swedish. And a bunch of other languages from all over the world uses similar constructions with their local words.

Equivalents of ordinateur is also not uncommon outside of French: European Spanish, Asturian, Galician and (sometimes) Portuguese use ordenador. Catalan uses ordinador. Basque uses ordenagailu.

To add an additional french speaking voice above those you already had work on this–

“Je suis Error” is more notable not for keeping Error in English, but for using an unusual form of introduction. Like how in Spanish you would rarely say “Soy Stéfan” (and never “Estoy Stéfan”). Instead you would say “Me llamo Stéfan” or “My nombre es Stéfan”. In French, you would typically say “Je m’appelle Jean” (I call myself Jean) rather than “Je suis Jean” (I am Jean). I’m no linguist but my understanding is that this distinction gets to the heart of the the verb use of “to be”.

“Cave” is rarely used as such in French, you’d normally pick “caverne”. I’m second guessing myself as to whether “cave” is strictly a foreign loan word or if it ever existed on its own in French.

I don’t view “Arrête-toi et repose-toi ici.” as having more emphasis on “you” than English. It’s just a fairly common form of address in French. The weirder thing is the game tutoying me. The more common way would be “Arrêtez-vous et reposez-vous ici.” Again, like Spanish, it’s fairly common for things to use a more formal second person pronoun in these kinds of situations.

“Il n’y a personne” didn’t strike me as odd. Although it literally means “There is no one”, it’s pretty normal to drop the preposition “ici” in the sentence and have it still mean “There is no one here”.

Your offered translation on “Veux-tu aller chercher de l’eau” is incorrect, full-stop. That French translated to English is “Do you want to go look for some water?”, which is the original English sentence. You said “Can you go look for some water?”, which would in french be “Peux-tu aller chercher de l’eau”. I assume your translator mis-read, this is a fairly common simple French mistake. Peux from the verb “pouvoir” meaning power or ability, veux from the verb “vouloir” meaning desire or want.

Although “démon” and “diable” clearly suggest demon and devil respectively, both words are used somewhat interchangeably when saying the English “demon” in French. Your note implies there was a semantic drift, which suggests falling for a sort of weird false cognate. I found it odd that you called this out, given your previous work on the difficulty of translating “majin” or whatever from Japanese has highlighted this exact problem, but I guess you were relying on your French translators.

Finally, “Tu es un Héros d’avoir sauvé mon enfant.” seems correct to me — both in the French form and in your English form: “You are a Hero to have saved my child. Come.” It’s fairly normal to use the infinitive “to have” in English to imply cause and effect (i.e. “You’re so sweet to have brought me chocolates” and “You’re so sweet for bringing me chocolates” scan about the same) and no different in French.

It was cool to see this piece though, despite my nitpicking here! The veux/peux thing is definitely an error though!

^”Cave” is commonly used in Quebec to refer to a basement (ie “sous-sol”). There’s also “cave a vin” (not doing accents because of my keyboard, sorry) for “wine cellar” which seems to be used in France.

—

To add on to the post above (which is pretty much correct about everything IMO):

About the “Use keys in palaces they are found in” line, the translation under Meaning is incorrect. The French “Utilise les clés dans les Palais. Elles s’y Trouvent” is really “Use the keys in the Palaces. They are Found there”, so it’s at least grammatically correct, apart from weirdly capitalizing “Trouvent”. However, the original English sentence implies that the keys should be used in the same palaces where you find them, while the French loses that nuance, in my view.

The “do you know Bagu” line – The form you suggest, “tu connais Bagu?”, is more familiar, while “Connais-tu” is a more proper form for a question. As such, the first version is more common in a spoken conversation, while the proper form would be more likely to be used in writing (though if you’re writing dialogue, of course, then “tu connais” would work). That’s putting aside the issue of the pronoun “tu” (familiar) VS “vous” (formal) – this still matters in France, but in Quebec and Canadian French in general, practically no ones uses “vous” to address an individual unless they’re working in customer service or trying to sell you something, and even then it comes off as unnatural.

“Please save our town” – the French line pretty much had to have a comma. “Please” could have been translated as either “S’il-te-plait” or “je t’en prie”, either of which could have been placed at the beginning or at the end of the sentence, but in either case they have be separated from it with a comma. Think of it as using “if it pleases you” or “I beg of you” in English.

“The hole in palace is endless trap.” “Piege sans fond” sounds strange. A bottomless trap is not the same as an endless trap, unless it is a pit or a hole. “Piege sans fin” makes more sense, if you’re going for a vague and corny-sounding hint.

Regardless, very interesting piece. I had no idea this translation booklet existed. A common thing in french-speaking Canada was to have two booklets included with games – the English one and a cheap black-and-white photocopy in French. Other games used hybrid boxes with the US cover and the European back, typically featuring descriptions in several languages. Sometimes we also got the multi-lingual manuals. My copy of Sonic the Hedgehog came with a manul that had text in at least 5 or 6 languages.

Today, I learned that “tutoying” is a thing.

“That French translated to English is “Do you want to go look for some water?”, which is the original English sentence.”

So, my French is not great (not awful, but far from fluent), but given that this text appears when Link is standing in front of a fountain and that the English sentence says “get” not “look for,” wouldn’t “prendre” be more correct? “Chercher”, as I understand it (and please correct me if I’m wrong!), would only apply if he doesn’t know where the water is, which doesn’t seem to be the intent. Or do I not yet understand these verbs properly?

(I have no doubt that the French translators back in the 80’s were just given a text dump and were left to guess at which of the various meanings of “get” was intended.)

I’m not a proffesional translator, but as a native Spanish speaker I’d like to comment on the bit of the Zelda manual you posted:

-The “Hello, son” thing is translated literally, which makes it sound like he’s literally Link’s father to me. But I do know m’hijo (literally “my son” with the first syllable nearly dropped) is used in more or less the same sense as son, so maybe it’s just a matter of dialect. M’hijo is very rural, though, which is probably not how the scientist is meant to come across; and I’ve never seen it written “properly” with all its syllables, which makes me think I’m barking up the wrong tree.

– The potion shop shop lady goes from being like a student to him to being his old student.

-The translator uses “globos oculares” for “eyeballs”, which is technically correct but sounds odd. Globos oculares is a more technical and rarer term in Spanish than it is in English, both because it’s considerably longer and because the component words used are less usual than “eye” and “ball” (It literally translates to “occular balloons”). The fact it’s used twice in two sentences just makes it sound weirder. The translation also adds that they’re frog eyeballs.

– The translator doesn’t seem to have had any idea what “Uhoy hoy hoo!” might mean and just left it as-is. It’s much harder to decipher in a Spanish context, for two reasons:

1) The letters are pronounced differently. The most important bit is that the H is silent in Spanish, which makes the text sound pretty far from laughter (You can see the translator adjusting for it in the bottom of the first column; “Hohoho” gets rendered as “Jojojo”, maintaining the same sound). For example, hoo would be said as to Ooh (like, the sound you make when you’re marveling at something or suddenly understand something), though it’s not usually spelled that way.

2) There’s an actual word mixed in: hoy means today. If you’re trying hard to extract meaning from what seems like nonsense, you’ll probably pick up on this and try to use it to deduce the rest from it. Like, if I really, absolutely had to guess what the translation meant, I’d probably go for something like “He’s trying to say he’ll cook frog eyeballs today, but he’s so excited he keeps getting the word wrong”. Except he gets it right the second time but keeps repeating himself!

-“Eye drops for Biggoron” has the words for eye drops capitalized for some reason. It’s also worded a bit strangely (“occular drops” instead of “drops for the eyes”, which would be the easier and more common way of saying it), but it’s perfectly understandable.

Overall, the translation flows pretty well in spite of the mistakes. The only things that jumped at me at first glance were the laugher and eyeballs things, mostly the former. One thing I’m very curious about is if they made the classic “preservatives=preservativos” mistake, but the image cuts off just before that line. (For those that might not know preservativos=condoms. You can imagine how much laughter that false friend has caused over the years). From the rest of it, I’d guess they didn’t; the other mistakes aren’t a matter of using a wrong word but of not understanding the text correctly.

Whoa, thanks for the analysis! The Spanish text uses “conservantes” there, so sadly condoms didn’t make it into Spanish Zelda 🙁

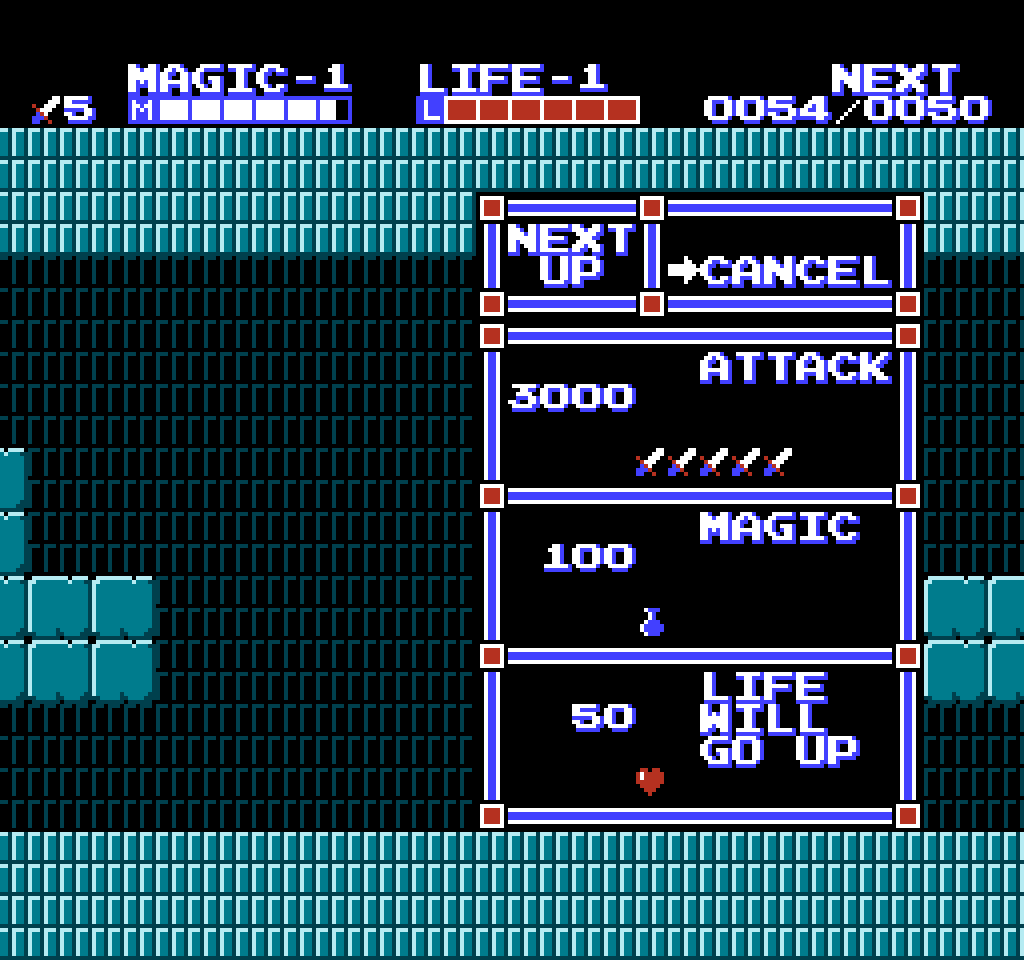

It’s hard to blame localizers for their ambiguous translation of “life”. Not only were games still new enough to have not locked nomenclature down, but Zelda II in particular has at least five contexts of “life”. One is the number of times you can die. Another is the amount of HP you have, expressed in bars/containers. Next there is the life level, which is really an armor rating. Then there is the Life spell, which restores HP. Finally there is the Water of Life, an item required to unlock the Fairy spell; confusingly, this same item was a consumable that restored HP to full in the previous game. Somehow, I think the game avoids using “life” in a philosophical manner, which is a somewhat impressive given the game is a bit bleak.

Because you mentioned that this is the Dutch/French version (which happened a lot during that time by the way), was there also a Dutch booklet there? Because I could give some insights in that and also I am very curious myself how this translation was done.

It unfortunately didn’t come with any Dutch stuff, even though the front of the manual says so.

Related to the translation booklet thing would be the original release of Wasteland. Due to how pressed for space the game was the script (which is quite verbose for a game of its era) for the game was on paper and the game told you to turn to particular pages to read dialog. It also had red herring sections for anyone trying to spoil themselves. As far as I know the game was only ever released in English though. I think the modern digital version actually includes this as a separate file but let you click on “Read Paragraph 2” in the game to show the accompanying paragraph on a pop up.

Quite a number of RPGs and adventure games from the early 80s did that. When you have very little space to work with, it’s definitely not the worst solution.

An English example of this in action: Taito USA cut all item descriptions from Lufia 1’s localization because of cartridge limitations, then included a leaflet with all of them with the game. Or the Asian version of a Mahjong/Go (?) game on the Famicom by none other than Nintendo that had English explanations of the rules and onscreen text.

It seems Ubisoft distributed a few PC Engine games in France with the most needed English/Japanese information to progress through the game translated in amateurish typed paper manuals, but nowhere near full translations.

It had to be a go game: Mahjong’s rules are so arcane and confusing there’s no way you could fit them in anything close to a reasonable size.

It was Mahjong. And the general rules weren’t explained in the manual, since the game was aimed at people that knew how to play mahjong already. It was a pretty straight forward translation of the Japanese manual, just with some additional notes about which Japanese words the game used to mean what mahjong terms.

The Wii VC release of Gley Lancer was (obviously) kept in Japanese, with translations for all the story text included in the digital manual.

Cutting out the item descriptions sure was baffling, especially considering Lufia II had even more items and equipment in its memory and those were all left in.

Hi, I own this game with this booklet, I’d like to add some things. For the first prints of adventure of Link in french and dutch, there was no booklet added with the game, the first print had a mini-dictionnary english to french and dutch to help to translate the game while playing, you can see that here : http://nintendoforever.free.fr/Nes/Zelda2TheAdventureOfLink/Zelda2TheAdventureOfLink_Notice.php?pageNotice=26

Then they finally add the booklet with the later print.

By the way, another game had a booklet like this one and I own it too, it’s “the battle of Olympus” as you can see : https://www.picclickimg.com/d/l400/pict/332940889120_/the-battle-of-olympus-nintendo-nes-complet-en.jpg

I agree about the fact that in the french booklet of adventure of Link, the translations are an abomination and don’t make any sense, but I suspect that they gave them the text already with mistake in english, sometime mixed with other text and did it without having the game.

As a Dutch person I wanted to comment on your nice picture of the booklet, because there are some weird translations in there. One of them is just wrong, in all context.

seashore = zeepaard = sea horse (should have been “strand”).

Others are just translated wrong, because I believe the translators did not have any context of the game. Ring = bellen = dial (should just be “ring” in dutch as well, as in an assesory for the finger. They probably thought it was a verb). Another example is magic potion = magisch = magical (should be “magische drank” or “toverdrank”) and cross = oversteken = traverse (should be “kruis” as there is a cross item in the game, they thought it was a verb again).

One of them is also kind of funny, because apparently they thought that “I am error” was an important line, because they also translated this as error = fout = mistake/error. But of course you know all about that line, that this interpretation is not really correct. I don’t really blame the translator here.

Huh, here’s a video discussing the Spainish OoT text guide: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_saTwX9mKc

The guy who made it seems to present an unnecesarily dramatic and confrontational version of the events, as evidenced by the video’s title. While the text guide wasn’t a perfect solution, I doubt it was the end of the world.

Yeah, this article clearly shows that early on most Japanese video games were translated to Japanese and English only until gradually the ‘golden six’ (ie. English, Japanese, German, Italian, French and Spanish) became the de-facto standard for a long time. Might as well include Korean, Chinese and Russian to that group as well depending on the game. As you can imagine, any language outside of that group happens to be too obscure to be bothered with (sorry, Finnish, Swedish etc…). At least now you know where our excellent English skills springs from.

How did Italian get that high anyways?

Italy is one of the least English-proficient countries in Europe. Selling games in English there is like selling Spanish-only games in the US – your average guy could prooobably bumble his way through it with a mix of remembering what he learned in school, guesswork and some occasional dictionary checking, but it wouldn’t be an overly enjoyable experience if the game had more than just fluff text.

In Hong Kong, PS2 games often come untranslated but are packaged with an additional leaflet containing an brief explanation of the game control in traditional Chinese and English. And the bottom section of the back cover is changed to show the game is still in Japanese while the manual is in Japanese/Chinese/English.

From now on I shall only refer to it as Spectacular Rock

Hi !

First, thanks for your amazing work.

I’m French, and i think that type of translations could be found in others games.

I’m almost sure that “Ecco The Dolphin” on Mega Drive, contains in its manual translations of the “in game” texts (which are in english)

I’m french too and own the game, there is no translation of the in game text in its manual.

Hello, have a lot of fun reading this article !

By the way, there is a translation booklet for the FAXANADU nes game too !

You can see it on this (little) picture :

https://encrypted-tbn0.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcQt4e41btwaWjeKmlhbHnisUYX6gBSl1uAKKBwp7rnqNz2NWavJ

Related fact: In the French version of A Link to the Past, the name of the Master Sword was localized as “Excalibur” for some reason. In Ocarina of Time it was renamed “l’épée de Légende” (“the sword of Legend”).

Sword in the stone legend, limited number of letters, they had to find a short name, even if I always disliked the name excalibur in Zelda (used again in windwaker and twilight princess, but renamed épée de légende in the HD version of this games), it was the better way to give a name to the sword. For Ocarina of time, they found a beautiful french name (épée de maitre is very ugly in french, even if now because of skyward sword, it should be translated as épée DU maitre).

What’s it called in Ocarina of Time?

épée de légende (Sword of legend), it was the first time they used it (even if in the instruction manual it’s called épée de maître (Master sword)). In fact my comments was not well written I should have write: “Since Ocarina of time, they use a beautiful french name. My bad.

I would like again to add a game with a booklet of french translation, it is Simon’s quest, if I manage to get it, I’ll scan it.