|

The Legend of Zelda was a truly epic adventure when I was growing up. But a big part of the experience was not in the game itself, but the instruction manual that came with it.

Unlike a lot of other games (especially Atari games), the Zelda instruction manual was big, in full color, and had tons of awesome art. I liked it so much that I would even take it to school with me and read through it during class and on the ride home after school. It was like a work of art, as far as game manuals were concerned.

Anyway, translating a game’s text is only one small part of a game’s localization – the manual plays just as big of a part in the process. So let’s take a look at the manuals now!

Instruction Manual Comparison

Not surprisingly, it turns out that the manual for the NES game is basically taken straight from the Famicom Disk System manual, writing, art, tips, and all. What’s surprising, though, is that the Japanese manual had even better presentation. I thought the NES manual had a lot of color and charm, but the Japanese manual tops it somehow.

For reference’s sake, here are older-quality PDFs of both manuals:

Cover Me Up

|

Here we see the covers for each manual. The gold of the NES manual matches the game and the box well, and the simplicity lends it all a very high-class, almost elegant feel.

The Japanese manual cover IS the “box art” for the Famicom Disk System version of Zelda. The art gives off a real adventure vibe that the NES manual art lacks.

You can also see that the pages have different dimensions – the FDS manual needed to be square-shaped to fit in the disk case.

Stickers For You

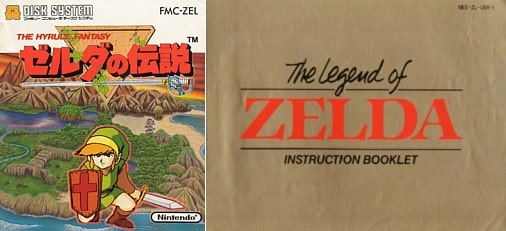

|

The FDS version of Zelda includes some stickers. Some stickers are for sticking “Side A” and “Side B” onto your disk, and the instruction manual goes into detail about this.

Some other just-for-fun stickers were included too, mostly of Link and the game’s logo.

As far as I can recall, the NES release of Zelda didn’t include stickers.

Hello, Disk-kun

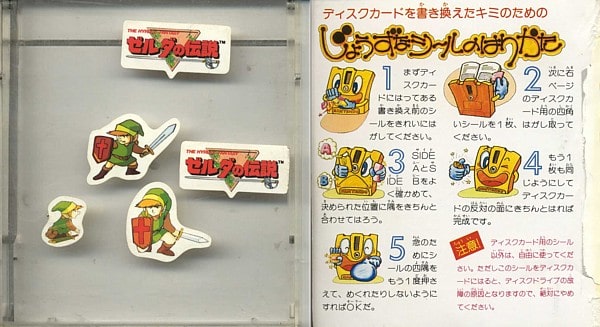

|

The Famicom Disk System had a mascot named “Disk-kun”. The FDS Zelda manual includes a lot of Disk-kun stuff, usually when discussing saving or when telling players how to properly take care of the disks.

Here we see Disk-kun being tortured in all sorts of ways while the manual says stuff like, “Keep the disk away from magnets! TVs and radios have magnets too, be careful!” or “Don’t touch this part!”

Since the disk system had nothing to do with the NES release, the NES Zelda manual has none of this stuff at all. Although it does of course give you the usual cartridge care warnings.

Save the Day

|

Once it’s time to save your game, the FDS version is really straightforward and there isn’t much to say than the usual, “Don’t turn the game off while the game is saving!”

The saving mechanism is different in the NES version, though. Save data in the NES version is kept thanks to a battery in the cartridge itself, and apparently there was a small chance that a power spike when turning the system off could cause the save data to get erased. So the way around this was to hold Reset and then turn the power off. If you played any battery-backed NES games back then, you probably know this very well.

Anyway, directions for this were also included in the NES manual (twice on this same page, in fact!) but Japanese gamers never had to do any of this crazy nonsense.

Now You’re Playing With Friend Power

One annoying part of The Legend of Zelda is that you can’t save the game anytime you want without purposely killing yourself.

Or so you thought? I remember not realizing it at first as a kid, but there IS a way to save your game anytime you want, and it’s written right here in the instruction manual! Just press A and Up on Controller 2 at the same time while on the item select screen:

|

Actually, the English translation of this gets it slightly wrong and says, “…press the A button on Controller 2 and the Control Pad.” Press the control pad? What?

In comparison, the Japanese version clearly says, “On Controller 2, press the A Button and the Up Button on the control pad.”

Anyway, pretty crazy code, huh? Why couldn’t they have just made it some kind of special option you use with Controller 1? Plus what if you don’t have a second controller? And what if the game messes up while you insert Controller 2, as it often did with me whenever I inserted or removed a controller during a game?

Well, as we’ve seen before, the Japanese Famicom has two controllers permanently attached to it, so none of this was a real problem for Japanese gamers. In fact, we saw how Controller 2 doesn’t go unused in the Japanese version – it’s the trick to killing Pols Voice!

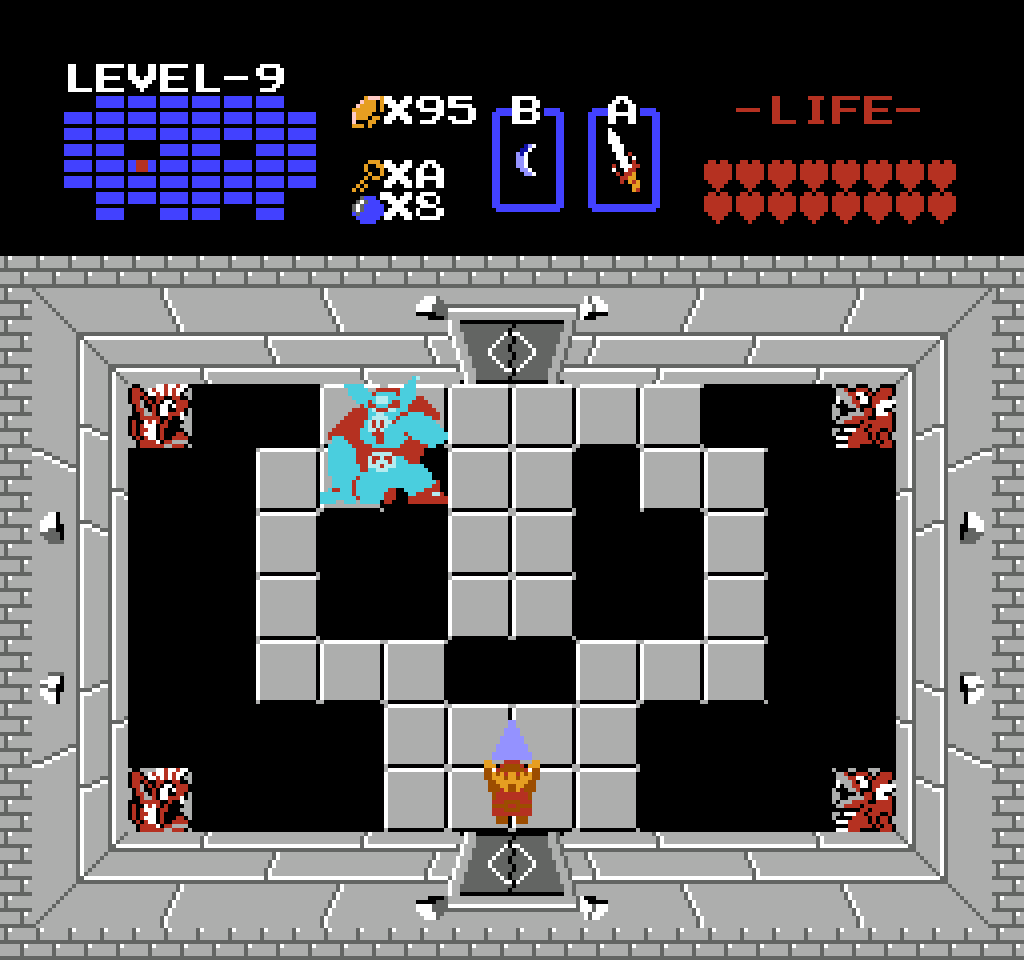

|

I still don’t know why they couldn’t have just made Select on Controller 1 bring up a save menu though. That’s more useful than the pause feature. Ah well.

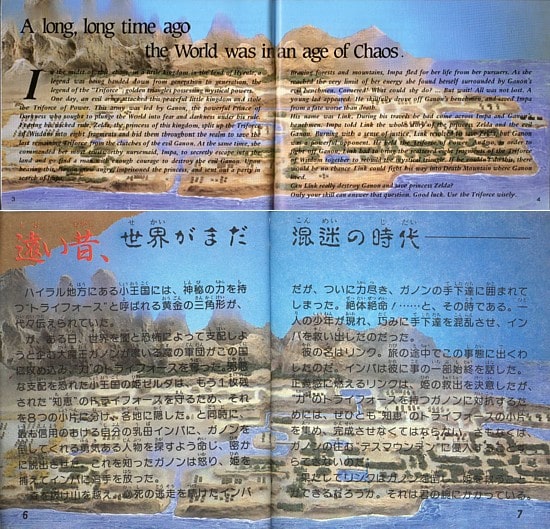

Story

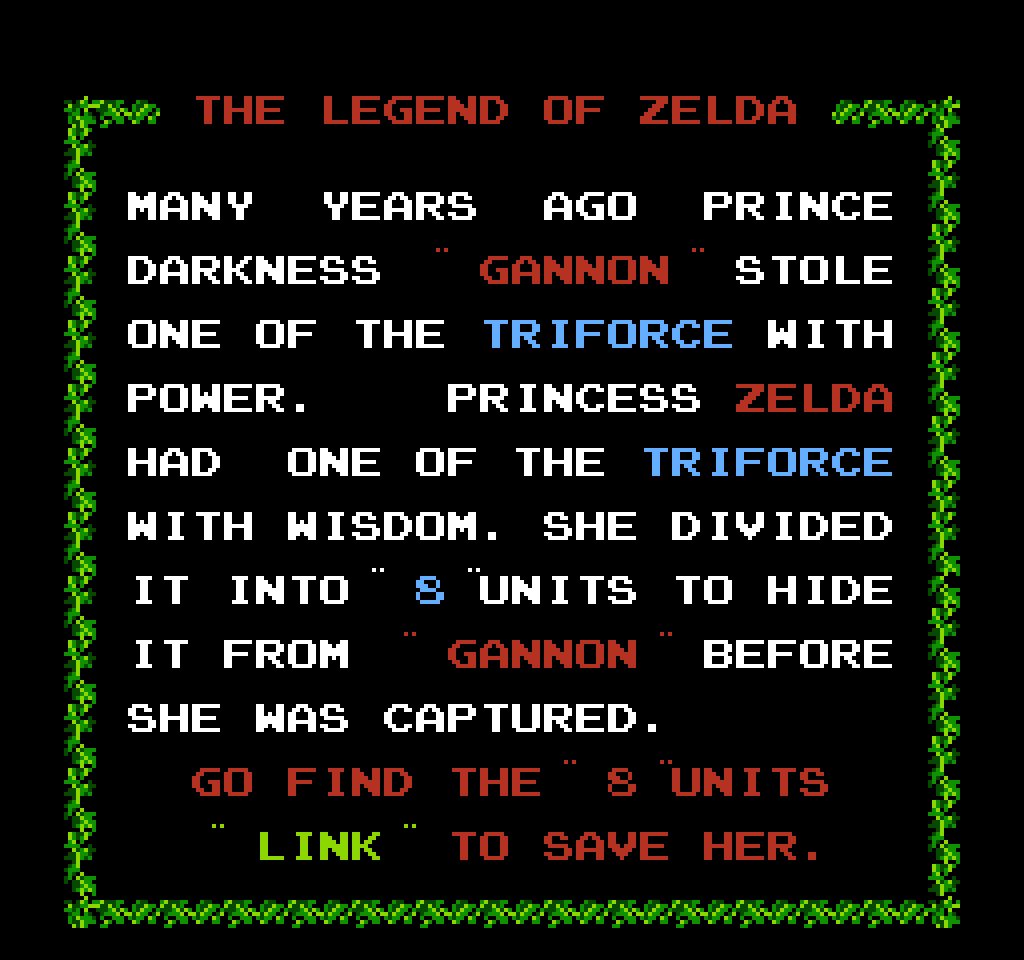

The game itself doesn’t give a whole lot of background information, so that’s where the instruction manual steps in. Both versions of the story are essentially the same, but since we’re here and since it’s an important part of the game, let’s take a look at it.

|

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | American Version |

| In the distant past, when the world was still in chaos… | A long, long time ago the World was in an age of Chaos. |

| In a small kingdom in the Hyrule region, golden triangles with mystical powers – known as Triforces – were passed down from generation to generation. | In the midst of the chaos, in a little kingdom in the land of Hyrule, a legend was being handed down from generation to generation, the legend of the “Triforce”: golden triangles possessing mystical powers. |

| One day, however, the Great Demon King Ganon, who sought to rule the world with darkness and fear, invaded this kingdom with his evil army and stole the Triforce of “Power”. | One day, an evil army attacked this peaceful little kingdom and stole the Triforce of Power. This army was led by Ganon, the powerful Prince of Darkness who sought to plunge the World into fear and darkness under his rule. |

| Fearing his evil reign, Zelda, the princess of this small kingdom, in an attempt to protect the remaining Triforce of “Wisdom”, split it into eight fragments and hid them throughout the land. | Fearing his wicked rule, Zelda, the princess of the kingdom, split up the Triforce of Wisdom into eight fragments and hid them throughout the realm to save the last remaining Triforce from the clutches of the evil Ganon. |

| At the same time, she ordered Impa, her most trustworthy nursemaid, to search for someone brave enough to defeat Ganon and helped her secretly escape. | At the same time, she commanded her most trustworthy nursemaid, Impa, to secretly escape into the land and go find a man with enough courage to destroy the evil Ganon. |

| Upon learning of this, Ganon grew furious, imprisoned the princess, and sent pursuers after Impa. | Upon hearing this, Ganon grew angry, imprisoned the princess, and sent out a party in search of Impa. |

| Impa desperately fled through forests and over mountains, but, eventually out of energy, she found herself surrounded by Ganon’s minions. | Braving forests and mountains, Impa fled for her life from her pursuers. As she reached the very limit of her energy she found herself surrounded by Ganon’s evil henchmen. |

| She was in a desperate situation! | Cornered! What could she do? |

| Just then, a lone boy appeared, skillfully confused the minions, and rescued Impa. | … But wait! All was not lost. A young lad appeared. He skillfully drove off Ganon’s henchmen, and saved Impa from a fate worse than death. |

| His name was Link. He came across this situation during a journey. | His name was Link. During his travels he had come across Impa and Ganon’s henchmen. |

| Impa told him the entire story. | Impa told Link the whole story of the princess Zelda and the evil Ganon. |

| Link, burning with a sense of justice, resolved to rescue the princess, but to stand up against Ganon and his Triforce of “Power” he absolutely must gather the fragments of the Triforce of “Wisdom” and complete it. | Burning with a sense of justice, Link resolved to save Zelda, but Ganon was a powerful opponent. He held the Triforce of Power. And so, in order to fight off Ganon, Link had to bring the scattered eight fragments of the Triforce of Wisdom together to rebuild the mystical triangle. |

| Otherwise, he won’t even be able to infiltrate Death Mountain, where Ganon lives. | If he couldn’t do this, there would be no chance Link could fight his way into Death Mountain where Ganon lived. |

| Will Link be able to defeat Ganon and save the princess? | Can Link really destroy Ganon and save princess Zelda? |

| It all rests on YOUR skill. | Only your skill can answer that question. |

| Good luck. Use the Triforce wisely. |

From professional experience I can tell you that this story was translated extremely well, likely by someone completely different from the rest of the manual and/or the game. You probably don’t even need to take my word for it though – pretty much everything in the English version says the same stuff, but generally better. Nothing was really lost, and no weird stuff popped up out of nowhere.

There are a couple minor points to note though:

- The English text says this takes place in the land of Hyrule, but the Japanese text says this is the Hyrule region. It’s a small nitpick, but the Japanese line makes it sound like Hyrule is just one tiny area of a much bigger land – which makes sense once you play the sequel!

- The English text says that a legend of the Triforces was handed down in this small kingdom. But the Japanese text says it’s the Triforces themselves that get handed down. That makes sense – Zelda probably wouldn’t have access to the Triforces if all that was passed down were legends.

- We see that the generic Japanese title of “Great Demon King” has become “Prince of Darkness”. That’s cool, that’s kind of a good equivalent phrase in English now that I think about it. Also note that “Great Demon King” was the title given to Bowser in Japanese Super Mario Bros.

- The English text actually adds in the blurb about “a fate worse than death”!

- The English text adds in a line at the end.

A few clunky parts aside, I’m really impressed with the translation of this story! It has the hallmarks of an experienced translator – for instance, a common thing among amateurs is to make one Japanese sentence into one English sentence, no matter what. But here, we see that complicated lines have been simplified by breaking them into multiple, shorter sentences with a more natural flow.

I’d almost think that maybe this was the result of a non-translator editor working with the text, but the fact that a lot of the nuances remained the same makes me a little doubtful of that.

In any case, good job, whoever worked on this!

Mean Ganon

|

In the tips section of the English manual, it says, “Link’s going to have a difficult time trying to destroy Ganon. He’s real mean.”

It’s being picky, but the Japanese version is more like, “As Ganon is very powerful, it will clearly be difficult to defeat him.”

There’s a difference between being mean and being strong – if being mean is all it takes to be difficult to defeat then the crotchety old men in the caves could probably take over the world.

This use of “mean” instead of “powerful/strong/tough” is actually repeated regularly throughout the English manual. It’s not a big deal, of course. I think I just found the line “He’s real mean.” to be a funny way to describe the Prince of Darkness and the game’s ultimate villain.

Boomerang

|

Although the story was translated superbly, most of the rest of the English manual suffers from weird, haphazard stylistic choices. Sometimes the guide will be talking in third person, then sometimes it’ll jump to second person (a lot more than the Japanese manual, anyway), like it’s talking directly to you. It’ll use really weird phrasing sometimes, but perfectly fine phrasing other times. It makes me wonder if different parts of the manual were translated by different people, or if some parts were rushed.

Anyway, I’ll use this boomerang entry to illustrate:

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| You can gain the upper hand in battle by switching between weapons (boomerangs, etc.), depending on the enemy you’re facing. Swiftly switching to the treasure select screen and changing equipment is vital to Link’s success in battle. | Carry weapons such as boomerangs etc. to match the enemy. This way Link can fight more effectively. The skill to switch over quickly to the treasure select screen (remember the sub screen?) and swiftly take out treasures is really important. If you’ve got this skill, Link will be able to win through to the end. |

My translation’s not 100% literal, but here you can see that the official translation has some awkwardness to it, and it adds a second-person reference (the “remember the sub screen?” part) out of nowhere. Some phrases, like “be able to win through to the end” are also overly literal, which is part of the reason for the awkwardness.

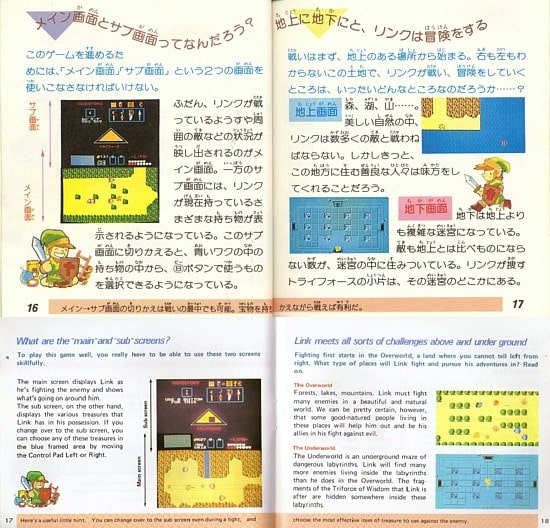

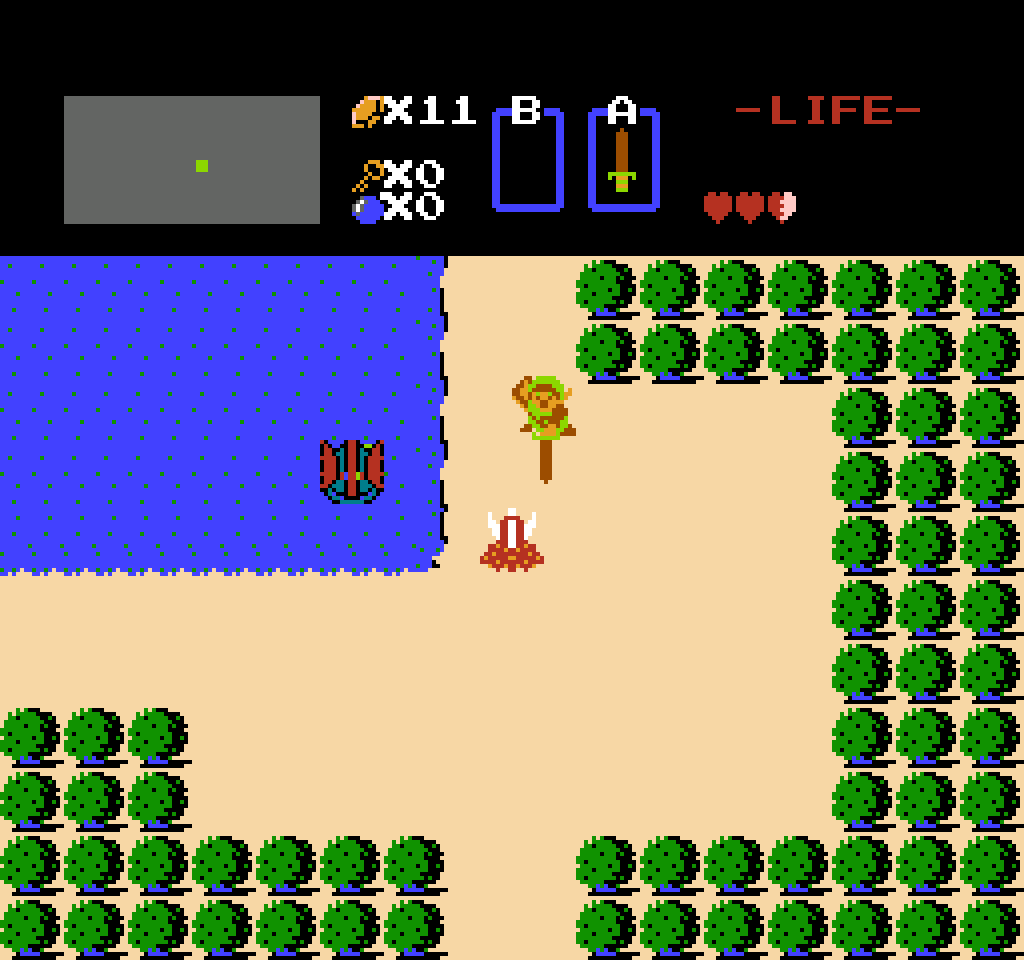

Screen Replacements

Although the text is (for the most part) the same in both manuals, sometimes the English manual uses completely different screenshots. I think this might be due to lack of screenshot assets when they were working on the English manual – they had all the hand-drawn art assets, but maybe they didn’t have any for the screenshots. At least that’s my guess.

|

Here’s an example – you can see that the English manual uses different screenshots. One of the screenshots even has a really strange black box around the map area, I wonder what that was about. It makes me think it might’ve been tampered with, but I don’t know why they’d do that.

Shield

|

A couple things to note with the description for the shield stuff. The main thing though is with the Magical Shield:

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Magical Shield Bigger than the original shield. It can block enemies’ spells and swords, as well as Zora beams. |

Magic Shield This is bigger than the other shield. Use it to fend off the enemy’s spells and rocks, and Zola’s ball. |

First, we see that the name has become the “Magic Shield” in the translation. It should be “Magical”, not only according to the Japanese manual, but the English version of the game too. How this change came about is anyone’s guess. It’s certainly not a big deal at all, but you’d think they’d at least check the names of these items with the list of items from the game’s intro. It’d only have taken them a minute to do so.

Next, the English translation says the Magic Shield blocks enemy rocks – but wait, the original shield does that already! This was a mistranslation for whatever reason – as you can see it should say “swords”, referring to the swords used by the Lynel enemies.

We also see it say “Zola’s ball” instead of “Zora beam” in the English translation. That’s fine I guess, they do seem more like balls than beams. But the use of the singular “Zola” here almost makes it sound like there’s only one Zola/Zora in the entire game!

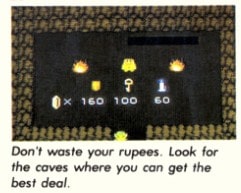

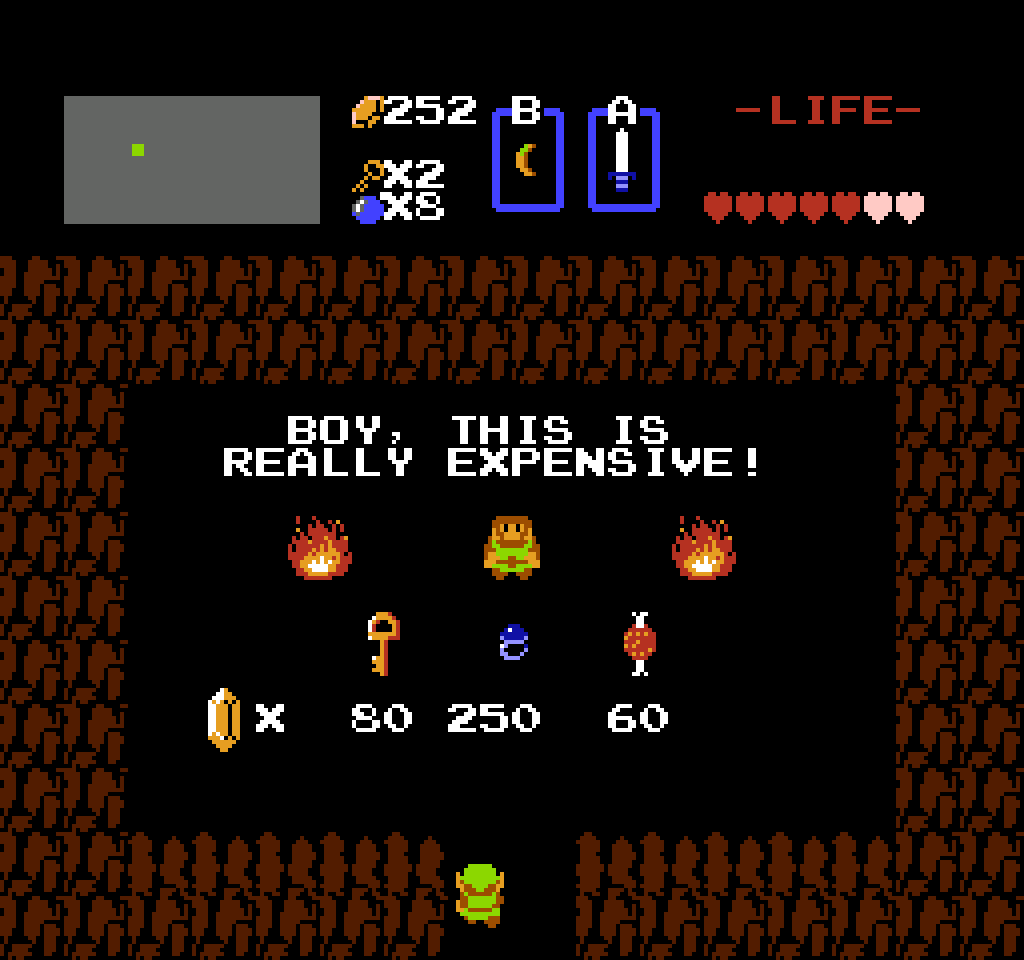

Rubies?

|

Here we see another piece of evidence that points to the manual translator not bothering to play the game’s intro. And, as we can also see, “Rupee” and “Rupees” were incorrectly translated throughout the English manual as “ruby” and “rubies”.

This mistranslation could be either due to the translator thinking, “You know, the original text is wrong, it should be ‘ruby’, ‘rupee’ isn’t a real word.” or it was a case of ルピー (Rupee) looking a lot like ルビー (Ruby), especially in small print.

Heart Containers

|

We saw during the game’s intro that “Heart Containers” go by the name of “Container Heart” in both versions of the game. But the Japanese manual actually calls them something like “Heart Bottles” or “Heart Flasks”. So they literally are containers. I never really stopped to think what “heart container” actually meant, so that’s kind of neat.

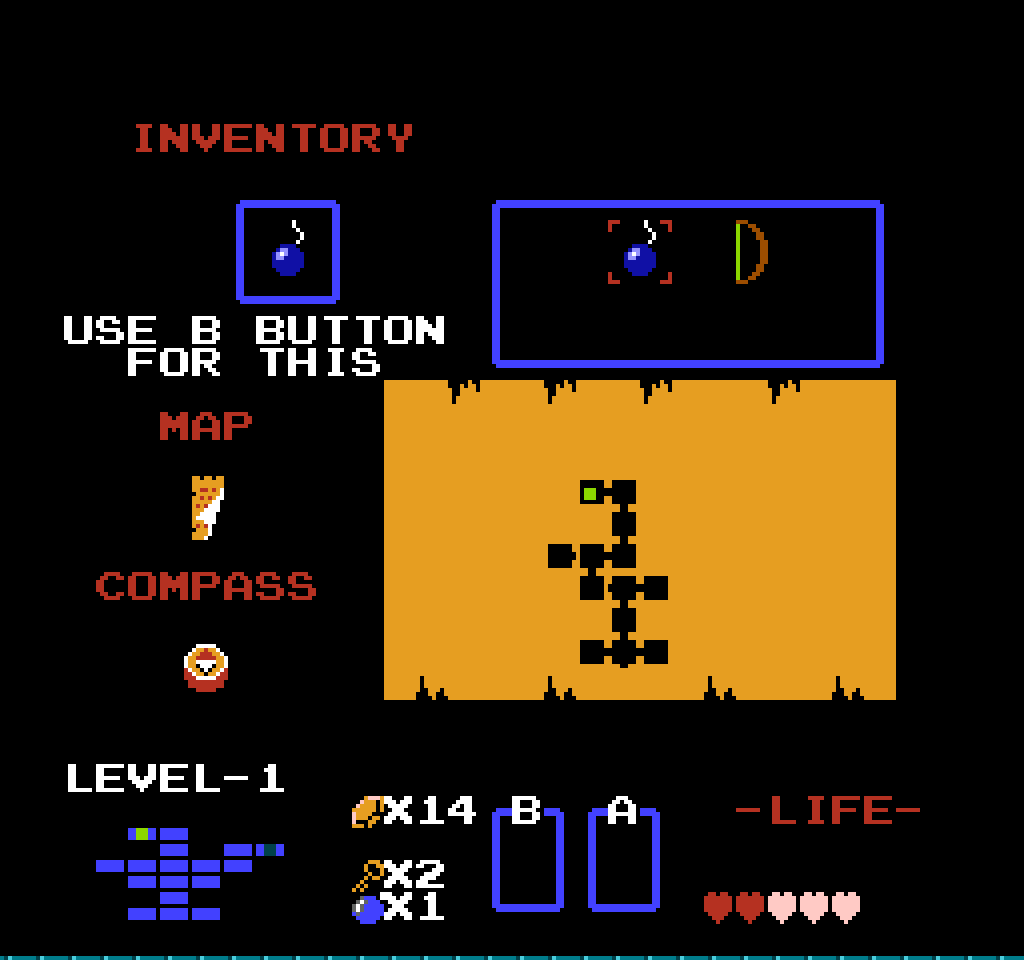

Super Key

|

The Lion Key item in the game is basically an infinite key item – once you get it you never have to worry about keys again. Also, when you have the Lion Key, the key indicator at the top of the screen says “A” instead of a number.

I never, ever knew what the heck the “A” stood for. It turns out that the Japanese manual has the answer!

|

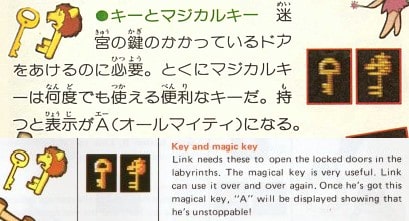

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Key and Magical Key These are needed to open locked doors in the labyrinths. The Magical Key is especially useful; it can be used over and over. When you have it, the display will show an “A” (for “Almighty”). |

Key and magic key Link needs these to open the locked doors in the labyrinths. The magical key is very useful. Link can use it over and over again. Once he’s got this magical key, “A” will be displayed showing that he’s unstoppable! |

Again we see the change from “Magical” to “Magic”, but then the description is inconsistent with that treatment. There are also other little issues, but the big one is of course that the meaning of “A” was completely lost in the translation!

I can only think that it due to a non-Japanese-speaking editor who came in and mucked with stuff; any competent translator would’ve left “Almighty” as-is.

Candles

|

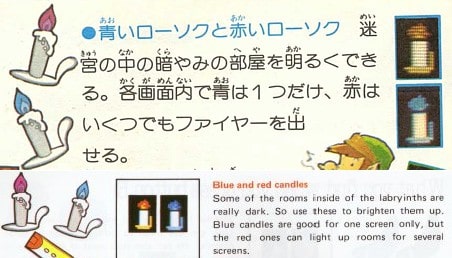

The English description for the candle items is a bit off – you don’t even need to know Japanese to realize that.

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Blue Candle and Red Candle With these, you can light up dark rooms inside labyrinths. Blue candles can only create fire once per screen, while red candles can produce unlimited fire. |

Blue and red candles Some of the rooms inside the labyrinths are really dark. So use these to brighten them up. Blue candles are good for one screen only, but the red ones can light up rooms for several screens. |

Whistle

|

Here we see that the “Recorder”, as it’s called in the game, is now called a “Whistle”. I don’t know if that’s the best term for this kind of instrument, but I’ll leave it at that.

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Flute A magic item that will cause all sorts of mysterious things to happen. |

Whistle A really mysterious, magical item. Use it and it’ll amaze you with what it can do. |

Bait

|

We already took a look at this hunk of meat item earlier. Here we see that it’s now translated as “bait” rather than “food”, so this manual text is a little better. The fact that the description talks about using it to lure enemies makes it 100% clear that the proper translation choice should be “bait”.

It would’ve been nice if they’d hinted in either manual that it can be used for other things too. That hungry Goriya in Level 7 must’ve stumped so many players…

Potions

|

In the game’s intro we see that these potions are called “Life Potion” and “2nd Potion” in English, even though the Japanese text says “Blue Water of Life” and “Red Water of Life”.

Here we see that “Water of Life” name used in both versions of the manual.

Magic Wand

|

Here’s another instance of “Magical” getting changed to “Magic”. Not only that, the Japanese manual calls it the “Magical Rod” while the English manual calls it the “Magic Wand”.

It’s not a big deal of course, but where the Japanese description mentions the “Bible” item, the English description correctly uses the new term: “Magic Book”.

The fact that the manual is finally consistent with the game’s intro makes it more clear that someone went through the translation at some point, combing specifically for this bible stuff but not really doing any other translation quality assurance.

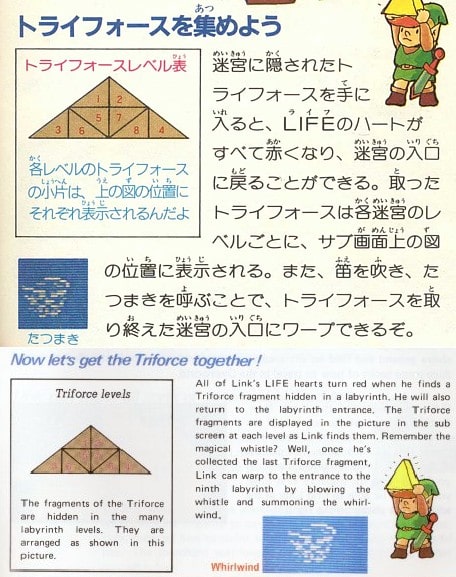

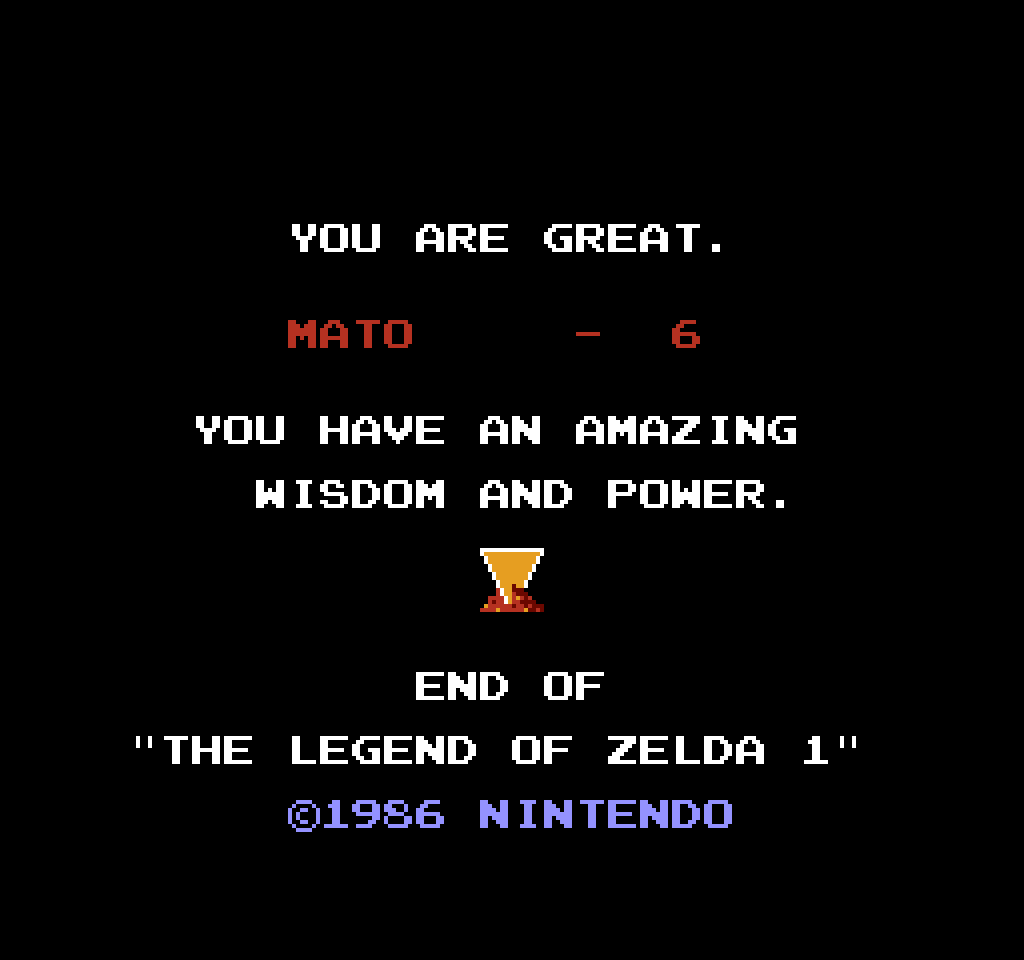

The Whirlwind Lie

There’s a huge lie in the English manual! It says that if you get all the Triforce pieces and blow the flute, you’ll be taken to the ninth labyrinth. As a kid, I couldn’t believe Nintendo would just lie to me like that!

|

It turns out this is actually due to a mistranslation. Here’s a side-by-side of this text:

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| When you obtain a Triforce hidden in a labyrinth, all of your life hearts will turn red and you can return to the labyrinth’s entrance. The Triforces you’ve taken are displayed in the diagram in the sub-menu, one for each labyrinth level completed. Additionally, by playing the flute and summoning a whirlwind, you can warp to the entrance of labyrinths whose Triforces you’ve finished taking. | All of Link’s LIFE hearts turn red when he finds a Triforce fragment hidden in a labyrinth. He will also return to the labyrinth entrance. The Triforce fragments are displayed in the picture in the sub screen at each level as Link finds them. Remember the magical whistle? Well, once he’s collected the last Triforce fragment, Link can warp to the ninth labyrinth by blowing the whistle and summoning the whirlwind. |

Basically, the Japanese phrase for “finished taking” somehow became “collected the last”, and the part about warping to the labyrinth entrances got changed beyond comprehension. Good thing this translation was just for a game manual and not for medical equipment instructions or something…

Octorok

|

Here’s another case of “tough” or “strong” being translated as “mean”.

In this case it doesn’t matter as much, since I’m sure they’re indeed mean, but it’s ever-so-slightly different from the original intended meaning.

Peahat

|

Here we see in the English manual that a Peahat is a “ghost of a flower”.

In Japanese, the term used is 化身, which has several translations. One is from Buddhism, and is often translated as an “Avatar” – one who takes human form to help mortal humans. The more common meaning is an “incarnation” of something.

Basically, it’s not necessarily a ghost, it’s just that “ghost” is probably the simplest alternative in translation.

Also, while we’re here, the English text says it “bounces around”, but the Japanese text says nothing about that at all, just that it flies around and flutters.

Molblins

|

We’ve already taken a look at the Molblins earlier, but here’s a side-by-side description for reference.

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Molblin A forest-dwelling goblin with a bulldog-like face. Attacks by throwing spears. A little tougher than an Octorok. |

Molblin A bulldog-like goblin who lives in the forest. He attacks by throwing spears. A little bit meaner than Octorok. |

Let’s get picky.

First, it’s their faces that are bulldog-like.

Second, we see “meaner” used again in place of “tougher”.

Third, “meaner than Octorok” is odd English – it makes it sound like there’s a guy out there named Octorok. This sort of singular/plural issue is common with native Japanese speakers trying to speak English, so it’s pretty likely that a native Japanese speaker translated this manual, possibly with a native English speaker there to fix up any glaring typos and grammar issues.

Lynel

|

The English description of the Lynel calls it a “guardian”.

In Japanese, it’s actually a “guardian deity”.

Also of note is that “strong” is actually kept as “strong” here. How strangely inconsistent.

Zola

|

We took a look at this enemy earlier. As mentioned before, the official name for this enemy is indeed “Zola” in the first Zelda game, mostly owing to the “l” and “r” issue among Japanese speakers.

The description is interesting as well, though:

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Zola A water-dwelling half-fishman that sticks its head out of the water. The beams it fires can’t be blocked by the small shield. |

Zola Half-fish, half-woman who lives in the water. When she sticks her head out of the water she lets out a ball that Link’s little shield can’t hold back. |

There are little issues here and there, but the big thing is that the English manual says that all Zolas are now female! Of course, the Japanese manual says nothing of the sort, so what’s the deal?

Even stranger is that something just like this happened with the Super Mario Bros. manual – the Cheep-Cheep description suddenly made all Cheep-Cheeps female!

My only guess is that the same editor worked on both manuals, and that either this person considered all sea creatures to be female for some reason, or was someone who uses “she” or “her” when confronted with the gender-neutral pronoun issue.

Zol & Gel

|

I always thought this “Gel” enemy in Zelda was pronounced like “jel”. But nope, the Japanese kana clearly indicates it’s a hard g, meaning the g is pronounced like the g in “gift”.

It’s likely that this word actually entered the Japanese vocabulary from a language other than English, in which case “jel” might be appropriate. But now you know how they pronounce this enemy’s name in Japanese at least.

Wizzrobe

|

The English description for the Wizzrobe starts with, “The Master of Movement.” Since the manual’s text generally doesn’t capitalize proper nouns as often as it should, you’d think this is an actual title or at least something official.

Turns out it’s completely made up, the Japanese text has no such proper noun/title.

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Wizzrobe Utilizes movement techniques to appear here and there, while unleashing spells that can’t be blocked by a small shield. Quite tough. |

Wizzrobe The Master of Movement. He appears here and there letting out magic spells that Link’s little shield can’t hold back. He’s pretty strong. Watch out! |

Darknut

|

As noted earlier, Darknuts are actually called Tartnucs in the Japanese version of the game. Just for reference, here’s the description in both versions:

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Tartnuc A labyrinth-dwelling knight with great offensive strength. Parries attacks from the front with its shield. |

Darknut The knight who lives in the labyrinths. He has lots of attacking power. He repels Link’s attacks from the front with his shield. |

I guess if I had to point something out, I guess I feel like the use of “The” at the start suggests there’s only one of these guys in the game.

Gibdo

|

The description for the Gibdo is slightly off in the English translation.

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Gibdo A mummy man. Has a high offensive power owing to its supernatural strength. |

Gibdo The mummy man. He’s got some strange powers, and some pretty powerful attacking force. |

If you’re not familiar with the word, the word 怪力 seems to mean “strange/mysterious” and “power/strength”. That’s where the “strange powers” in this translation comes from. But 怪力 actually means something like “abnormally strong” or “superhumanly strong” – maybe even “Herculean strength” in some cases. So this particular description difference is due to a mistranslation.

Plus, contrary to what the English manual says, Gibdos don’t have any strange powers at all in the game, they’re just normal ol’ enemies.

Manhandla

|

As noted earlier, this “Manhandla” boss in the English version was called the “Testitart” in the Japanese game.

What’s really interesting though is it’s description:

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Testitart A four-limbed, jumbo-sized Pakkun Flower. Speeds up with each limb lost. Possesses somewhat powerful offensive strength. |

Manhandla A large man-eating flower with hands sticking out in all four directions. It moves faster as it loses its hands. It’s pretty mean. So, watch out! |

Again, we see “strong/tough” changed to “mean”. But the really interesting thing is the deal about the “Pakkun Flower” in the Japanese description. As we saw in my Super Mario Bros. localization comparison, Pakkun Flowers are the Japanese name for Piranha Plants!

I guess the translator wasn’t aware of this, so it wound up just becoming “man-eating flower”.

|

In short, this boss is actually a reference to Super Mario Bros.! I never would’ve known had I not checked the Japanese manual all these years later. I bet I would’ve loved that cross-game connection as a kid!

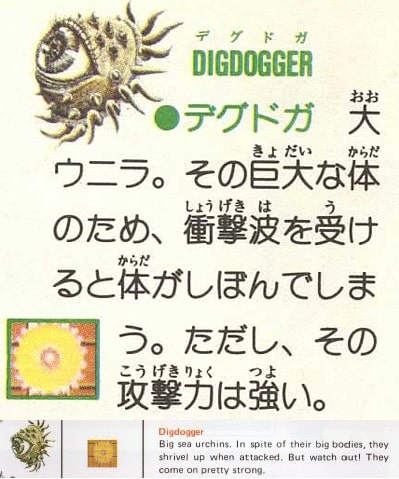

Digdogger

|

Another boss in Zelda is called a “Digdogger”. Its description is interesting as well, so let’s take a look:

| Japanese Version | American Version |

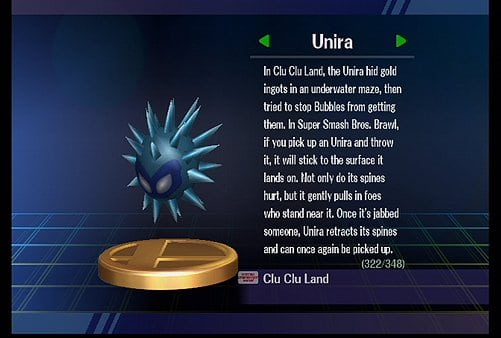

| Digdogger A giant Unira. Due to its enormous size, shockwaves will cause its body to shrivel up. However, it has powerful offensive strength. |

Digdogger Big sea urchins. In spite of their big bodies, they shrivel up when attacked. But watch out! They come on pretty strong. |

A couple issues here. First, the English translation is wrong – this boss doesn’t shrivel up when attacked, that’s what makes it so different from other bosses.

Second, the deal about “shockwaves” is admittedly a little strange, but at least it sort of gives a hint about not being able to beat it via normal means. In comparison, the English hint steers you the wrong way and doesn’t give you any vague clues at all.

Lastly, the Japanese text calls it an “Unira”, but the English text just calls it a “sea urchin”. “Uni” means “sea urchin”, but this is an “unira”.

…What’s an “unira”, you ask? Well, to be honest, I had no idea either until I did some quick online checking. It turns out it’s the made-up name of the sea urchin-like enemies in Clu-Clu Land, another Nintendo game from the time:

|

There’s even an entire entry about it in Smash Bros. Brawl:

|

Remember how in Link’s Awakening there’s a bunch of character cameos from non-Zelda games? It turns out this has been happening since the very first game! Just none of us knew it because the English manual didn’t translate stuff properly.

|

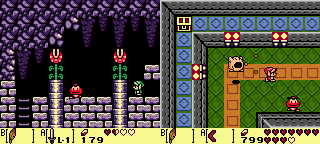

Bubble

|

The description for the Bubble enemy is slightly different as well:

| Japanese Version | American Version |

| Bubble A hitodama. When possessed by it, you’ll be unable to draw your sword for a while. |

Bubble The spirit of the dead. When it clings to Link, he won’t be able to unsheath his sword for a while. |

First, we see that the Japanese one uses the word “hitodama”. This is from Japanese folklore – it literally means “person soul” and is a type of fiery apparition that does various things, but is mostly what we might call a will-o-wisp. So the English translation isn’t wrong by any means, it just technically has more to it than being a simple spirit. The translator made the correct choice to simplify it for the English manual.

The main issue here though is that the word とりつかれる is mistranslated as “cling to” – which is an understandable enough mistake. It’s actually closer in meaning “to possess” in this context, like when you’re possessed by a ghost or spirit. So apparently touching these things possesses Link temporarily, which is why he can’t draw his sword.

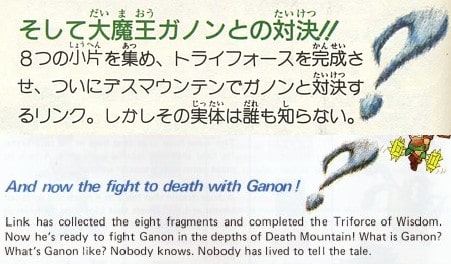

Deadly Fight

|

In the Japanese version of the manual, this header text says something like, “And now the confrontation with the Prince of Darkness!”

The English manual says, “And now the fight to death with Ganon!”

What’s most interesting about this is that Nintendo of American added a reference to death here. In just a few years the term “Nintendo game” would become synonymous with “censored for family-friendly happy fun time”. It’s neat seeing how that attitude wasn’t as prevalent in the early NES days.

Old Mystery Man

Another interesting change between the two manuals is the first old man in the game who gives you the wooden sword.

In the Japanese manual we see him offering Link the sword, with some text above his head. Nothing really out of the ordinary:

|

But in the English manual, we see a completely different screenshot:

|

Wait, what?! The old man is offering Link the choice between the sword and a boomerang? That’s not in the game at all! My guess is that this screenshot was actually from a really early, unfinished Japanese version of the game, with the old man’s text covered up.

Actually, this “let’s cover up the Japanese text” thing happens pretty regularly in the English manual and in other English materials. That’s why all the screenshots with people speaking seem strangely empty:

|

And here we see the text very blatantly covered up:

|

I bought the Zelda Tips & Tactics guide way back in the day, and I remember thinking as a kid, “Why is all the text blank? Why does it look covered up over in the corners?” Well, now you know why, young me!

- More and better pics of the different games, boxes, manuals, etc. side-by-side

- A closer look at why NES players needed to hold Reset when turning the game off, what the potential harm is in forgetting to, and the technical reason behind it

- A quick look at the NES cartridge’s actual battery

- A look at how Zelda I’s map and Zelda II’s map connect

- A brief discussion on overly literal translations

- Six examples of other Zelda/Nintendo character crossovers

- Three manual hints with odd translations

- More on the “sword or boomerang” option that was originally present at the start of the game, and the collective mis-remembering we’ve all had about it

No Comments