Last year, Nintendo released miniature versions of the Famicom and NES systems that came with a number of classic games pre-installed on them. Nintendo often makes small changes to its classic games without saying anything, so I enjoy hunting for those tiny changes whenever I can. And this time I was especially interested in how Zelda 1 changed this time around. I managed to borrow both systems from a friend and streamed both games earlier this week while searching for changes.

|

| For simplicity, I call these the 'Famicom Classic Mini' and 'NES Classic Mini' |

Essentially, these new releases are strange hybrids of previous versions, with a few new changes of their own sprinkled in too. More than anything, I think these changes offer a neat example of how a translated game can affect its source material – usually it works the opposite way.

The Many Versions of Zelda

First, I should point out that there already exist multiple versions of Zelda 1. On the Japanese side, there used to be 3 main, distinct versions: the original Famicom Disk System version (1986), a bugfixed Famicom Disk System version (year unknown, likely 1986), and the Famicom cartridge version (1993). All re-releases and ports afterward were based on one of these three versions.

On the English-language side, there were multiple versions as well. The original NES cartridge release (1987), a slightly updated version that changed the save screen (year unknown, likely 1987 or 1988), and a version with a slightly revised script (2003). All releases ever made were based on one of these three versions. Naturally, most of the modern re-releases and ports have been the 2003 version, but not all.

|

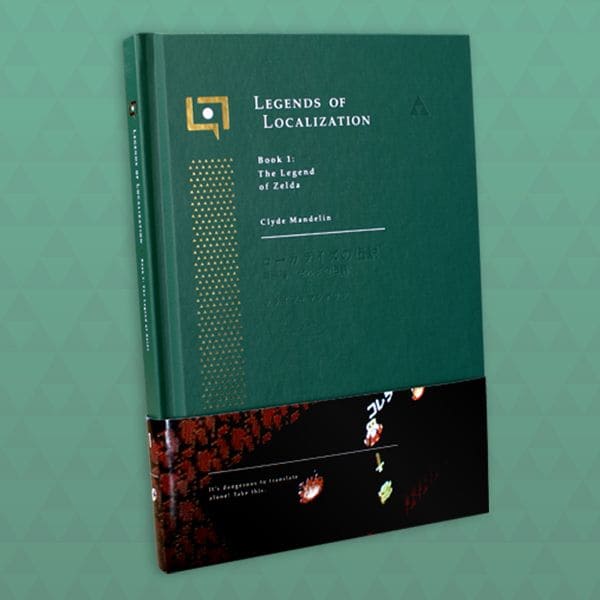

Anyway, if you’re curious about all of the differences between all of these versions, I wrote a book that goes into great detail comparing all the version changes, translation changes, gameplay changes, and a whole lot more here.

The Famicom Classic Mini’s Zelda 1 Changes

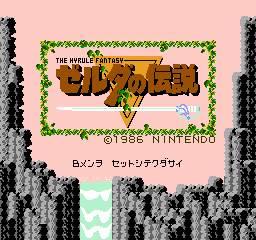

To answer a number of common questions I’ve gotten: the Famicom Disk System screen still displays when you start the game. The game still has loading time and loading messages. There are no simulated loading sounds. Disk flipping is handled automatically. The music and sound effects are from the Famicom Disk System version and not the very different-sounding cartridge version.

Now, let’s look at the actual changes.

Title Screen

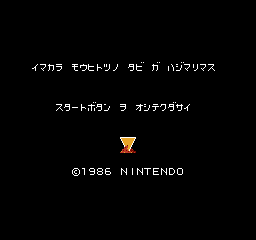

The game’s title screen has seen a number of tiny changes over the years. The 2016 release appears to have the 1986 release’s title screen (notice the ダ and the big 1 in particular) but with a minor text edit added.

|  |  |

| 1986 version | 1993 version | 2016 version |

Font & Intro

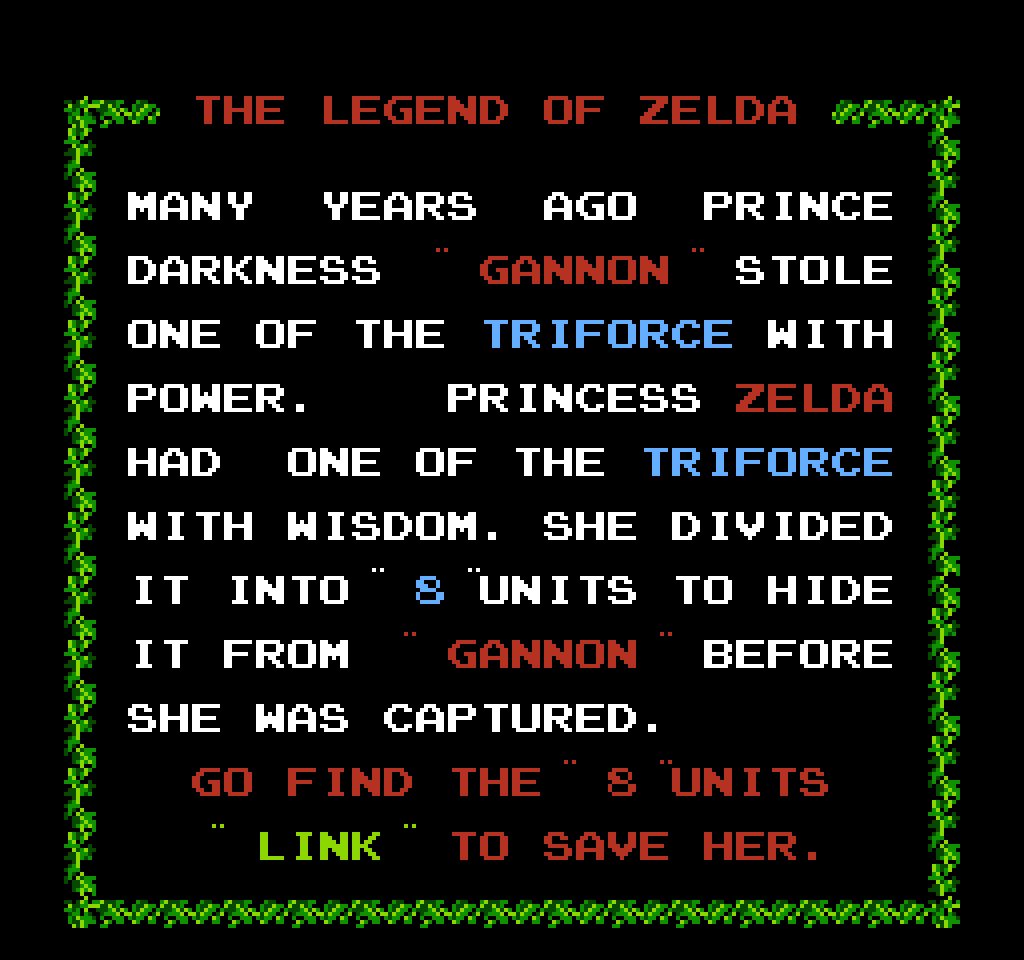

The original 1986 version of the game featured a slim English font. This was replaced with the chunkier NES English font when it was re-released on cartridge in 1993. The Famicom Classic Mini version uses the original slim font.

Additionally, the Japanese intro has featured bad English since its very first release. This intro was re-written for the 2003 English revision, however, and the Famicom Classic Mini version is the first Japanese release to use this newer text.

|  |  |

| 1986 version | 1993 version | 2016 version |

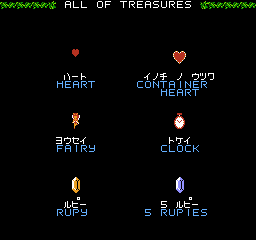

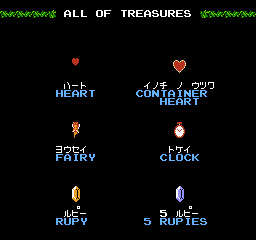

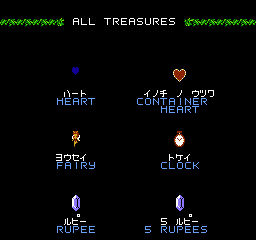

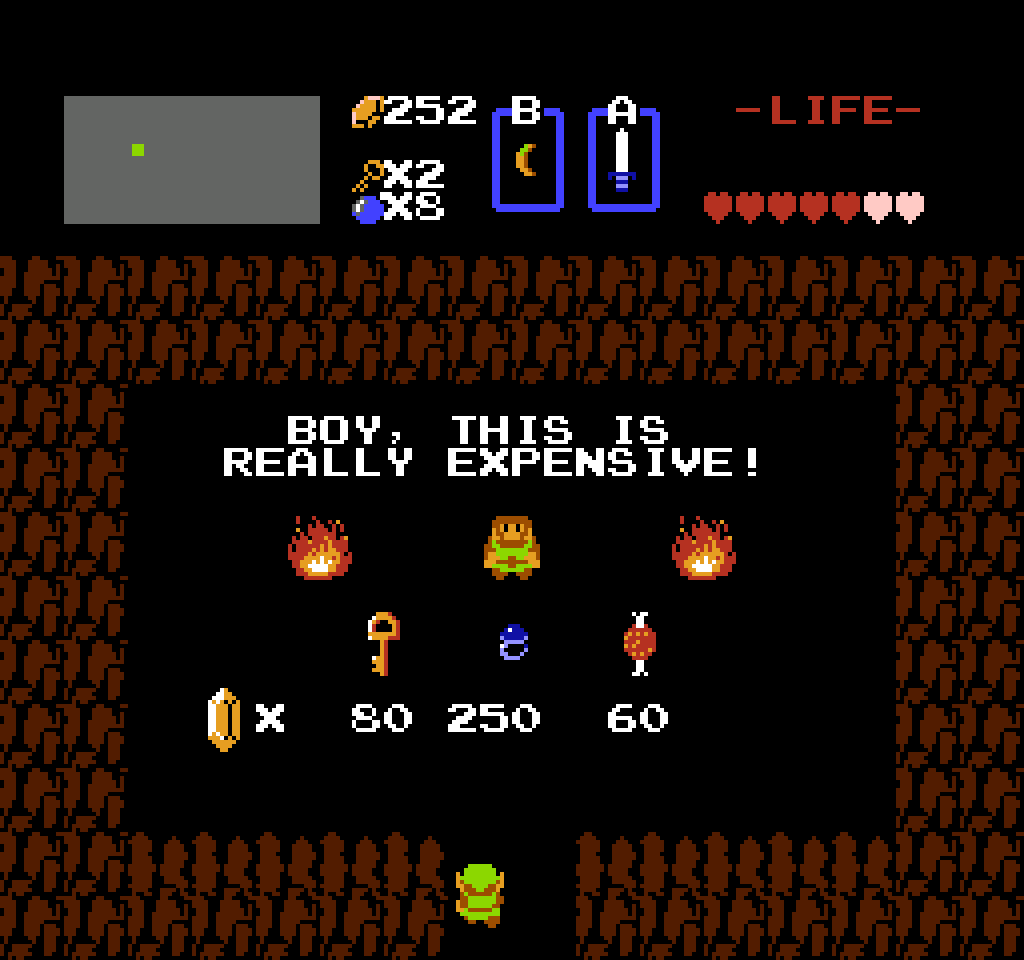

The “Rupy” spelling remained the same across all the Japanese releases until the Famicom Classic Mini version, which uses the 2003 English revised spelling of “Rupee”. The Famicom Classic Mini version also uses the 2003 English text “All Treasures”, unlike all of the previous Japanese releases.

|  |  |

| 1986 version | 1993 version | 2016 version |

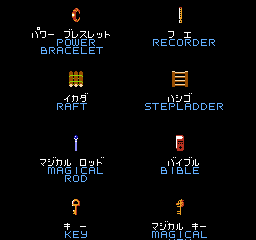

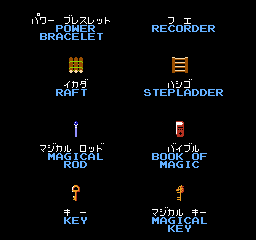

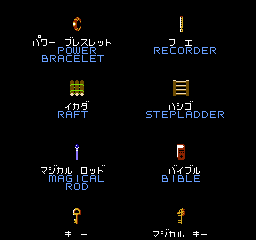

The original “Bible” item was changed into the “Book of Magic” for the NES release. This name was adopted by the 1993 Famicom cartridge release. But the name is back to “Bible” in the Famicom Classic Mini release.

|  |  |

| 1986 version | 1993 version | 2016 version |

In short, the Famicom Classic Mini version so far is a strange chimera of the original release, the 1993 release, the 2003 English release, and some new stuff.

Pols Voice

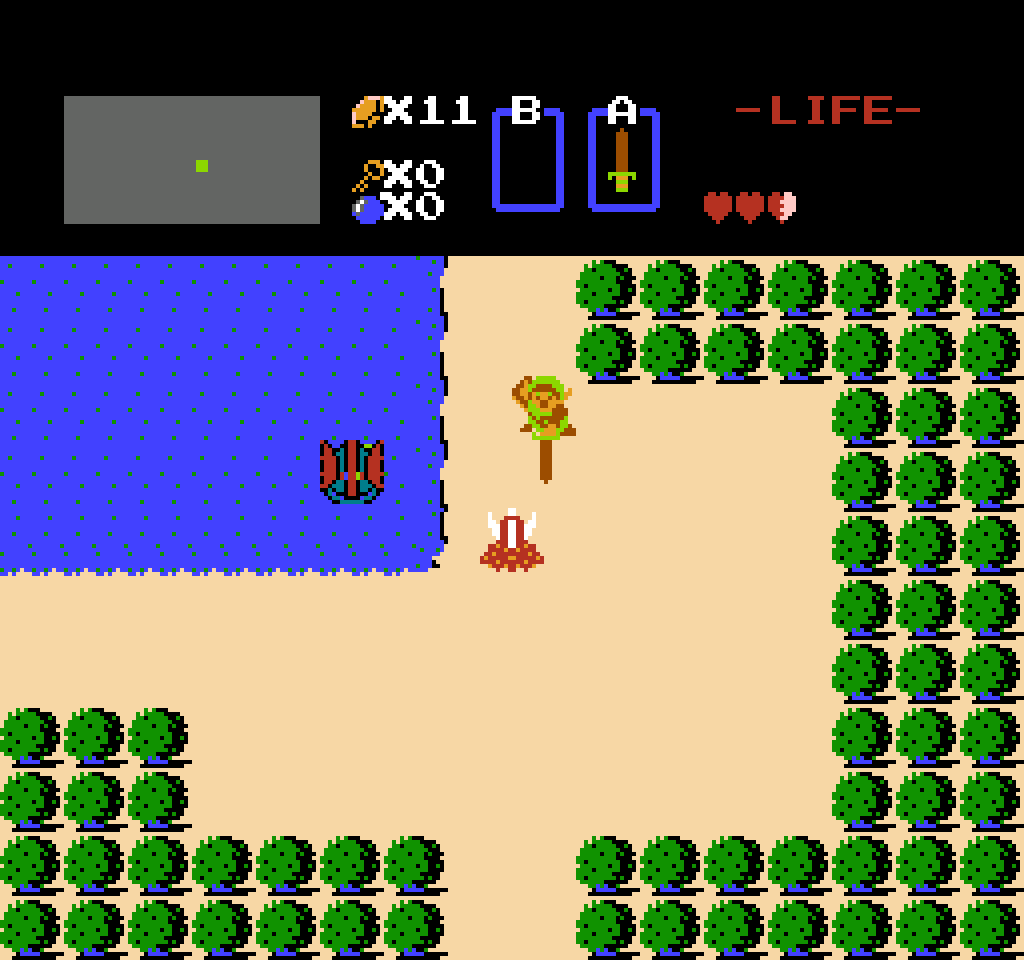

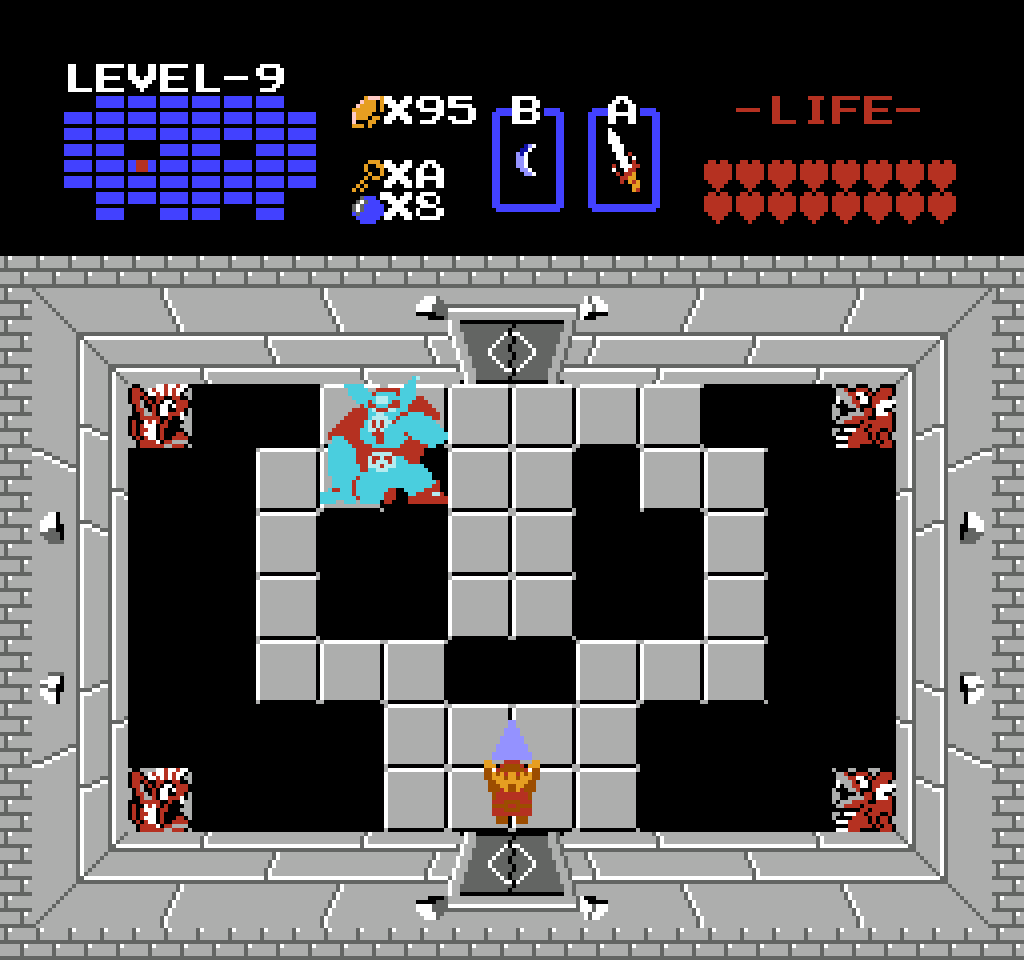

In the original Famicom version of Zelda, you could easily defeat the Pols Voice enemies by using the microphone built into the Famicom’s second controller:

Of course, this was a problem when the game was re-released and ported later on, because none of the later systems had a Controller 2 microphone. So Nintendo updated the game each time to support this feature. For example, in the Game Boy Advance port, pressing Select four times kills the Pols Voices. In the Wii Virtual Console release, twirling the right analog stick of a Wii Classic Controller kills them. Every release has had its own unique solution to the Famicom microphone problem… until now.

|

The Famicom Classic Mini comes with two controllers attached to the system, but Controller 2 doesn’t have a microphone. Instead, it’s just molded to look like it has a microphone. The official site also mentions that microphone functionality isn’t supported. Given this, I assumed that the programmers would’ve given the player a different way to do the Pols Voice instant death trick, but it appears not. After a lot of Internet searches and rumor-testing, it seems that the Pols Voice trick can’t be done. They can still be killed with a sword, like always, but a memorable part of the game’s mechanics has been lost.

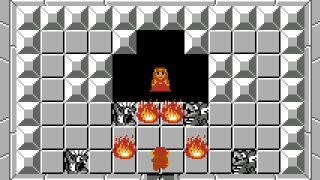

Flashing

Most Virtual Console games tend to have some sort of flashing screen countermeasures that seem to be automatically handled by the emulator running the games. Zelda seems to have been affected less than other games so far, but the Famicom Classic Mini’s flash mitigation is clearly different. Here’s the original game and the Famicom Class Mini version side by side:

|  |

| Original | Famicom Classic Mini |

The Famicom Classic Mini version also ends on a gradient fade that probably wouldn’t be possible on an actual Famicom/NES.

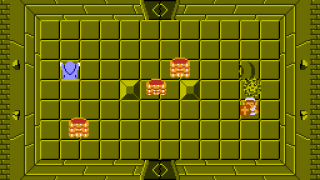

Bat Rooms

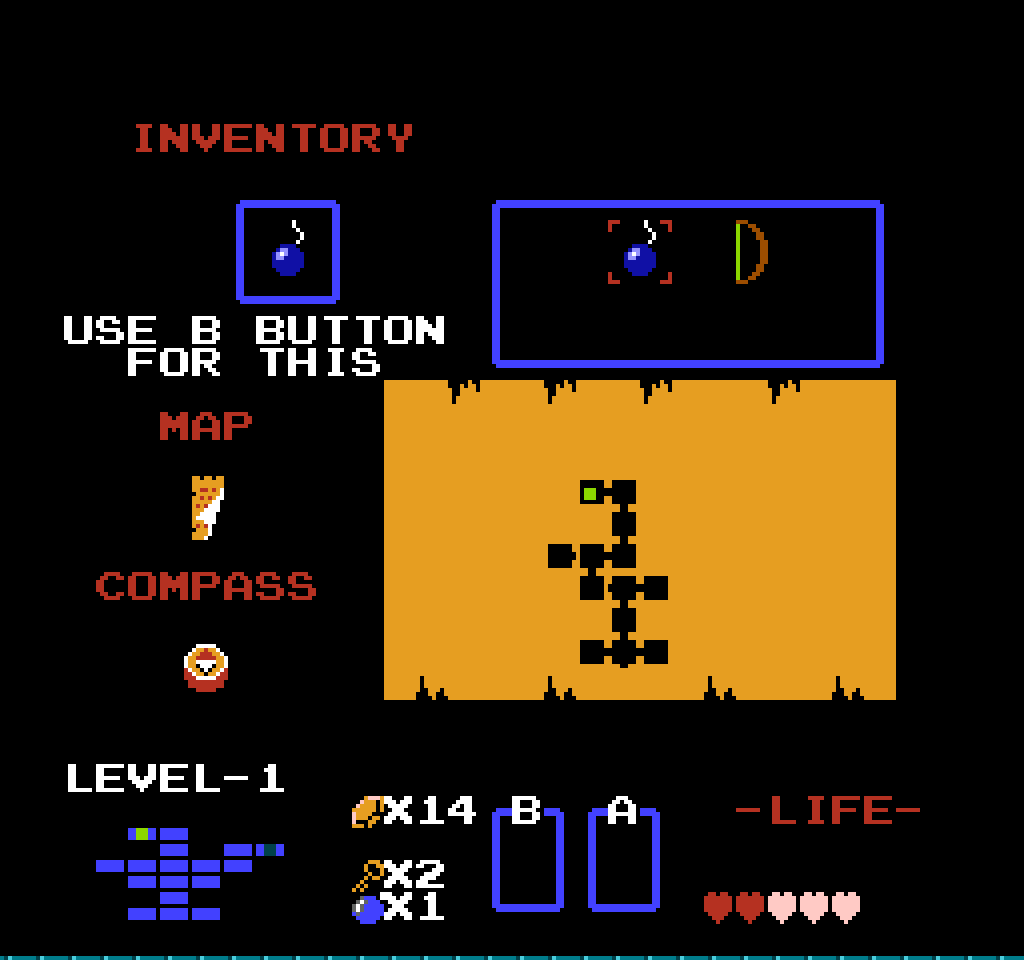

In the original version of the game, there’s a room in Level 4 and a room in Level 5 with a key and nothing else. These lonely rooms were filled with bats in the NES release, and this found its way into the 1993 Japanese version of the game too. In the Famicom Classic Mini version, though, the bats are absent again.

Heart Container Trick

The very first Japanese version of Zelda (often known as 1.0) had a programming oversight that let players get lots of extra Heart Containers just by using the flute. This was fixed for the bugfix release (often known as 1.1) that came out shortly after.

In this instance, the Famicom Classic Mini version appears to behave the same way as the 1.1 release. No extra Heart Containers for anyone.

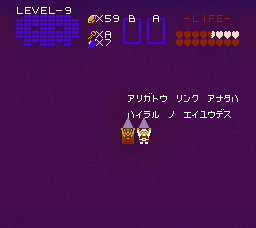

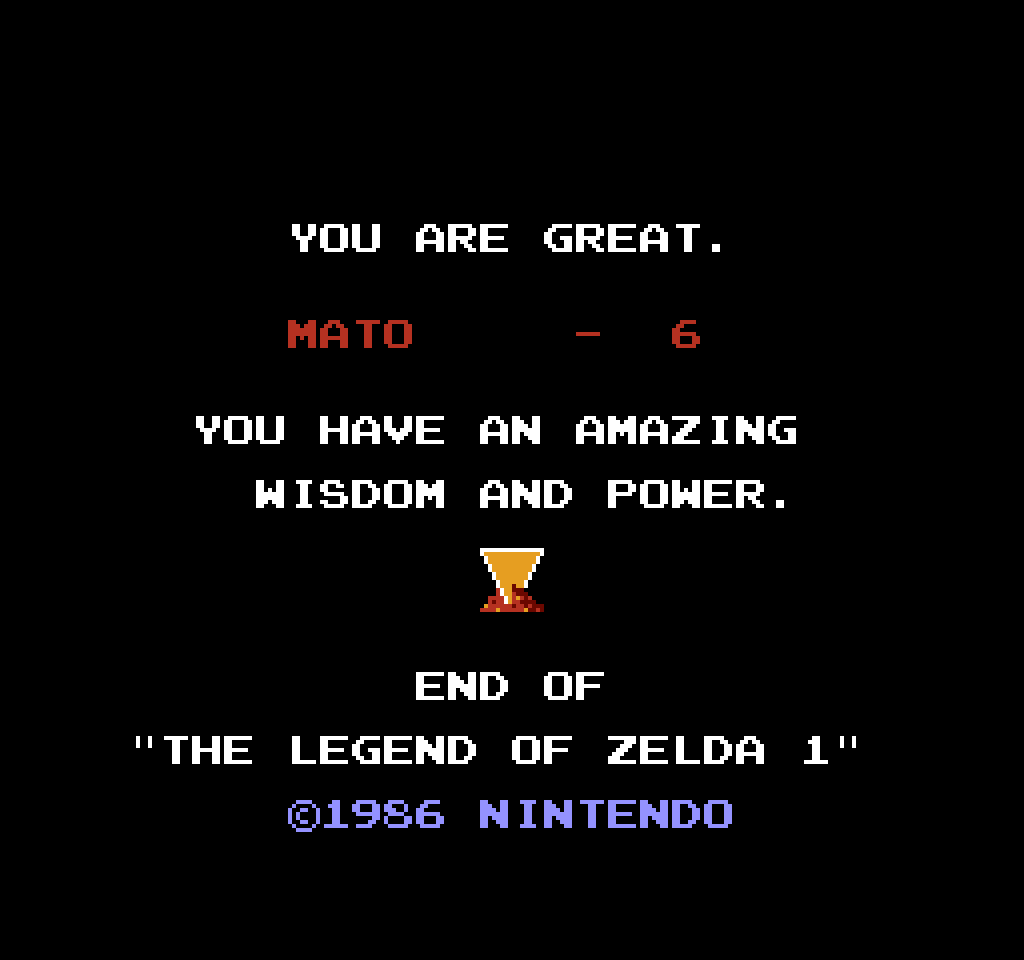

Ending

The ending has a few changes too. First, the flashing screen after Link and Zelda hold up the Triforces is less flashy and purpler than the original game. Link and Zelda disappear also from the screen afterward, just as they do in the 1986 version of the game. (Note: Link is a weird color on purpose in the screenshot below and isn’t a result of the Famicom Classic Mini)

|

Most interesting, though, is that the final screen has a typo of sorts. I assume it happened when someone tried to edit a previous version’s copyright info.

|  |  |

| 1986 version | 1993 version | 2016 version |

The NES Classic Mini’s Zelda 1 Changes

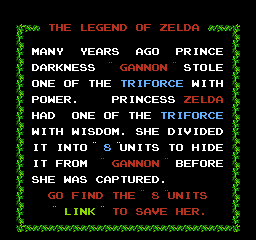

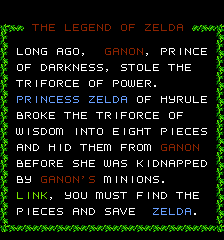

The NES Classic Mini version of Zelda 1 is a hybrid of previous versions as well. In particular, it appears to be the original release with the 2003 version’s script inserted and a few minor changes made elsewhere.

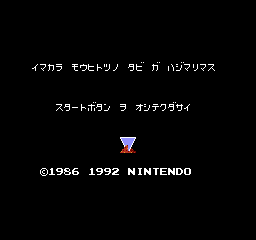

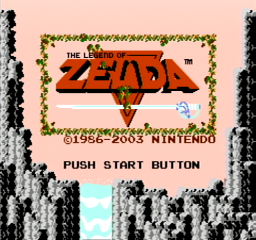

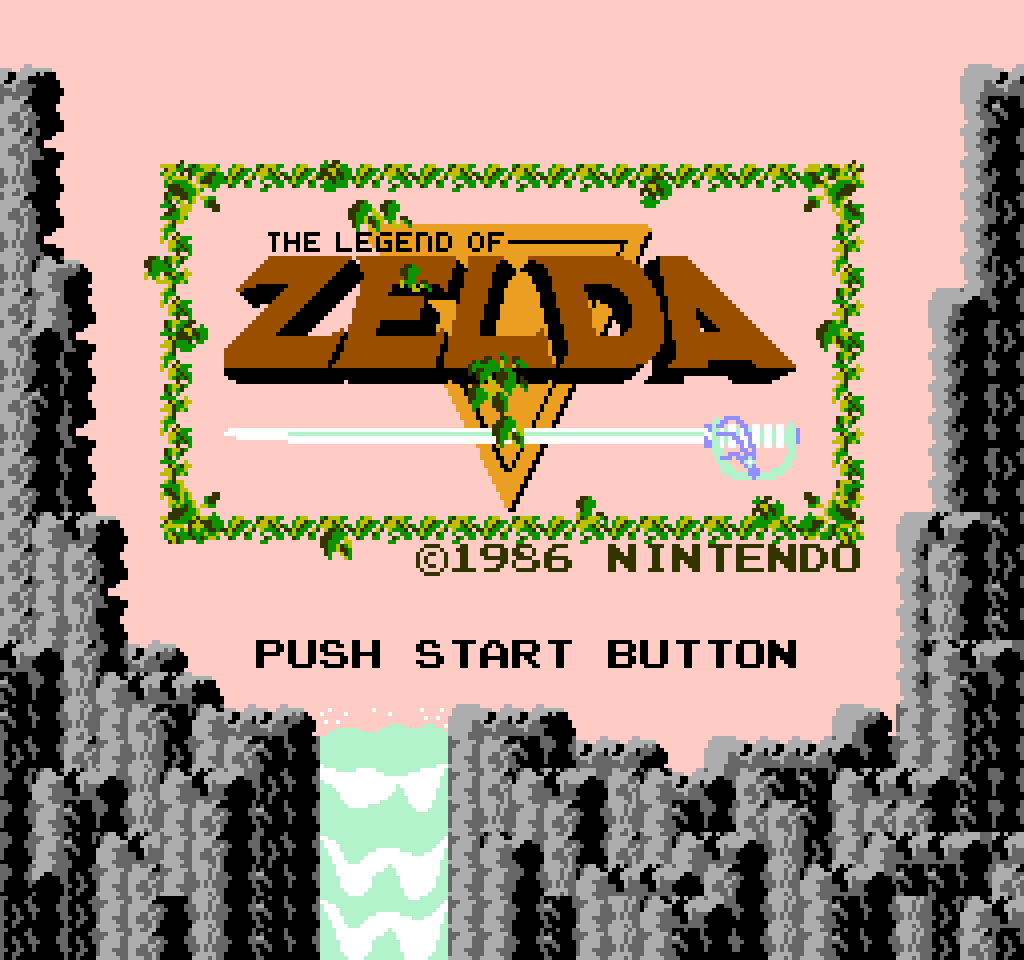

Title Screen

The title screen is the one thing that has had clear changes over time, but even then there were only three versions. The NES Classic Mini ignores the two most recent updates and uses the very first title screen.

|  |  |  |

| NES release | GameCube version | GBA version | NES Classic Mini version |

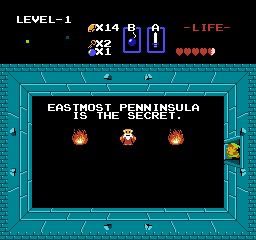

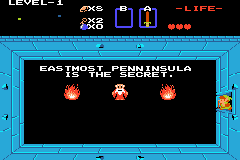

Eastmost Peninsula

The infamous hint man in Level 1 used to talk about an “eastmost penninsula” in the English translation. It took almost 30 years and two script revisions, but the typo is finally fixed.

|  |  |

| 1986 script | 2003 script (GBA screenshot) | 2016 script |

This is the only text change that I’ve found so far. The rest of the script appears to be from the 2003 revision, which means there are still some genuine translation issues.

Flashing

The NES Classic Mini version of Zelda has the same screen flashing change found in the Famicom Classic Mini version. The screen also flashes various shades of purple after rescuing Zelda exactly the same way the Famicom Classic Mini does.

|

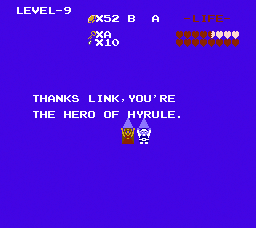

Ending

The final screen underwent a tiny change for the 2003 script revision, but the NES Classic Mini version reverts it back to the original version.

|  |  |

| 1986 version | 2003 version (GBA screenshot) | 2016 version |

Possibly More Changes

I found the above changes after one playthrough of the Famicom Classic Mini and NES Classic Mini versions of Zelda. It’s very likely I’ve missed some other changes, especially given that I haven’t tried the Second Quest yet. I’d bet there are other changes to the programming as well.

The only way to reliably find these differences is to look at the game’s ROM data, but I haven’t found a way to dump the ROMs from the Mini systems yet. But even if it is possible, I assume the ROMs will end up being identical to the original games. This is because the Virtual Console systems patch games in RAM at runtime, so it’s very likely that the same thing happens here. In which case, we’d need to find a way to dump the system’s RAM whenever a game is running. That sounds even harder, though. Still, if anyone out there with technical know-how can help, please let me know. I’d love to take a look at Zelda II in a similar way too sometime.

|

Anyway, that’s all I’ve found for now, but if you happen to discover anything else that I’ve missed, let me know in the comments. Sometime in the near future I’m going to summarize all this for my Zelda book’s “patch page” chapter, so if you’ve already bought the book, keep an eye out for that!

I wonder how many of the other games on the classic editions also received updates like this. That’s pretty interesting that they’re still updating stuff instead of just simply repackaging the same version. It’s kinda nice to know that they’ve actually done a bit more than simply wrap up the existing versions just to ship it out and make buttloads of money.

Have there already been multiple revisions of Zelda II? I don’t think I recall enough specifics about the dialog in that game to notice if there’s differences. If it wasn’t such a hard game, and the fact that the battery in my NES cart is probably dead I’d almost consider comparing the NES version to the GC/3DS VC versions 😛

Yeah, whenever there’s a new release of anything I always wonder, but I usually don’t have the money to spend on wild goose chases. A few things I’ve checked before this have had quiet little changes too, like the Breath of Fire II script changes for the VC. I bet changes are pretty common, just nobody is really looking.

I’m not sure about Zelda II, that’s something I was hoping to look into eventually, whenever I do a full Zelda II project. I might give it a quick whirl sometime to see if any of the text changed at least.

Oh man, I’m a real nut for version differences. It’s always fascinating to see the little tweaks developers make to make different versions of the same game unique.

I may add this to TCRF later if you don’t mind.

Of course, TCRF kicks butt and our interests overlap so much that I consider us teammates in the war against Giygas.

So the Japanese script hasn’t changed at all?

I didn’t do as thorough of a check of the Japanese text due to time but I plan to take a closer look soon.

Something strikes me as really weird about the way they changed the name of the “Bible” item: since both the Japanese words and the direct English translations of those words are displayed for most of the items, the 1993 version could be read as implying that “Book of Magic” is the meaning of the English word represented by 「バイブル」. I wonder if that could have actually made it more likely that people would assume “Bible” was just a generic word for a book of spells, rather than less.

And even as a kid, I’d assumed that the money was supposed to be called “Rupees” ever since I found out there was a real currency called rupees that was used in India. (I don’t know where I first learned that; probably from Carmen Sandiego.) But now I’m actually not so sure. I’ve played a lot of Japanese RPGs that make references to Indian mythology (Rudra no Hihou probably being the most prominent example there,) but if the money was always supposed to be “Rupees”, then that would be conspicuous as the only reference to Indian culture in a setting that otherwise seems to be based on Western European culture (thus it has things like Bibles, crosses on shields, and fairies that look like beautiful women with wings rather than youkai.)

Given that the Rupee items in the games have always been made to look like jewels, and how common it is for very slightly modified words and brand names to show up in Japanese pop culture (you might see characters in an anime drinking Bepsi, or watching Somy televisions,) I honestly wonder now if the 「ルピー」 in the first game could have been conceived as a warped version of “rubies”, like they were a kind of jewel from a parallel universe or something.

It’s certainly possible. With how everyone thinks of the most obvious thing when they hear the word, they don’t seem to realize that bible with the first b in lower case simply means a detailed manual or book on a subject (like the Tales of the Abyss Character Bible; the first b is only capitalized because it’s a book title, which is just proper English). And from bible do you get words like bibliography, which has nothing to do with religion.

Rupees are called rubies (“Rubinen”) in German Zelda localizations.

Nice breakdown of all the differences. Just to make things even more confusing. There’s yet another version of the FDS-version of Zelda, which I’m pretty sure this 2016 version is based on, which is the Collection on Gamecube released in 2004, it’s the Japanese equivalent of that 2003 compilation disc we got but the versions of the first two games are the FDS versions with the 2003 text cleanup.

If I recall correctly, the FDS-version on that GC-disc has all these differences you listed besides the copyright info, it’s copyrighted 2004 and the title screen says PRESS START instead.

Btw, I own that Japanese GC-collection disc, so if there’s anything you want me to check, let me know.

Cool, thanks for the info! I think that was the one version I haven’t been able to get my hands on due to insane prices.

The NES Mini apparently runs on a variant of Linux. In dact, Nintendo even released the source code for the Operating System’s kernel (which can be found on their official website).

Nintendo apparently decided to base the NES Mini (and its Famicon variant) entirely on the Allwinner R16 “System On the Chip”, presumably to save costs. It’s even possible to hook a serial cable to the device itself, allowing one to directlt talk to the system’s Operating System.

Nintendo decided to base the NES Mini (and its Famicom variant) entirely on the Allwinner R16 “System on the Chip”, apparently to save costs. It’s even possible to hook a serial cable to the device itself and talk directly to the Operating System powering the device.

From the sound of those who did exactky that, Nintendo apparently decided to store almost each ROM image into their own seperare “partitions”. For those who aren’t tech-savvy, that’s the equivalent of having multiple virtual disks being stored inside one hard disk drive.

Let’s be honest, I think that the font used in original Japanese version is nicer than in the version we got. Makes it stand out somewhat.

The flashing screen change, to me, takes a little of the “pizzazz” out of the presentation.

I do understand though. Photo-epileptic people should be able to play these old games without worrying about seizures. I suppose all I would ask for is a feature to turn “off” the effect that dulls the flashing lights. By default, it would be “on”, and turning it off would pop up a warning that if the player is photo epileptic or expects to have guests watching who are, it should be left on, but once it is off, the flashing lights would function just as they did in the original release. I think that this balances out safety concerns with historical accuracy.

Answering to this post after a lot of time to give a little info.

The version of Zelda included with the NES games application given with Switch Online is the same as the NES Mini. Ditto for the Famicom version.

Does anyone know which version of the Famicon disk was released first? I’ve seen a couple different packaging variations: one has the yellow “Nintendo” visible at the bottom, but the other is entirely covered by packaging art. Just curious which one was original. Thanks in advance.