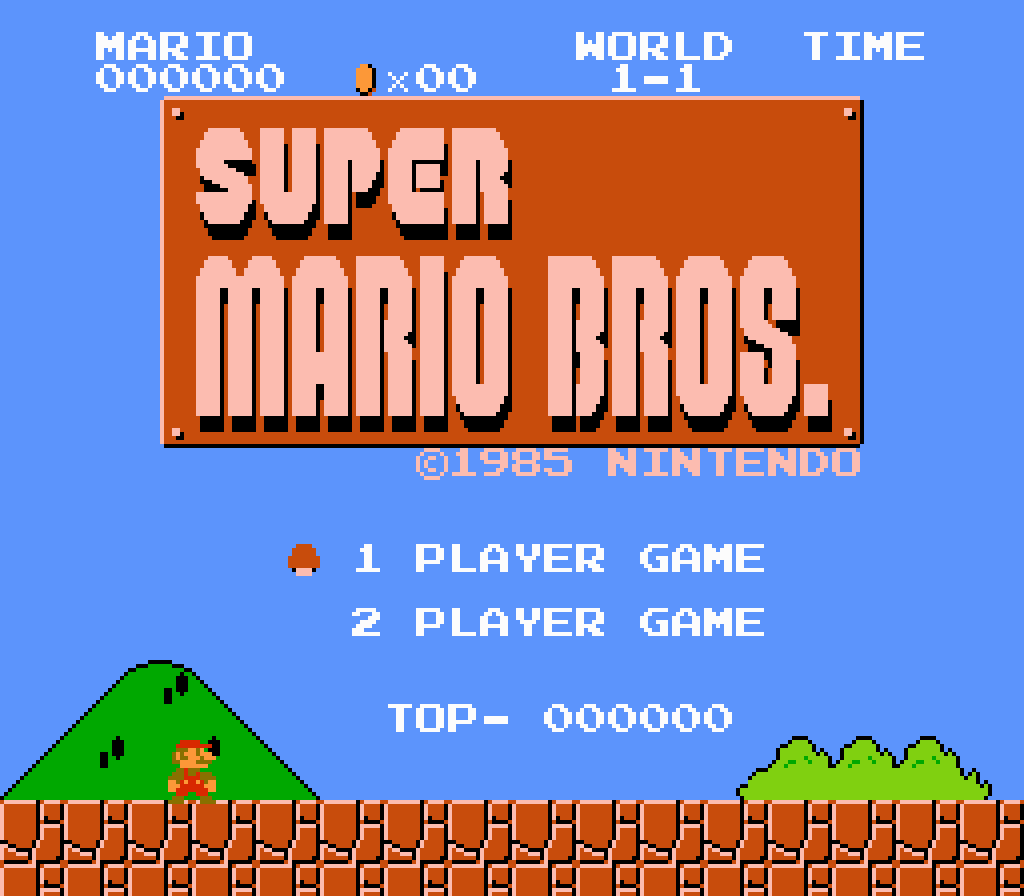

Are They the Same Game?

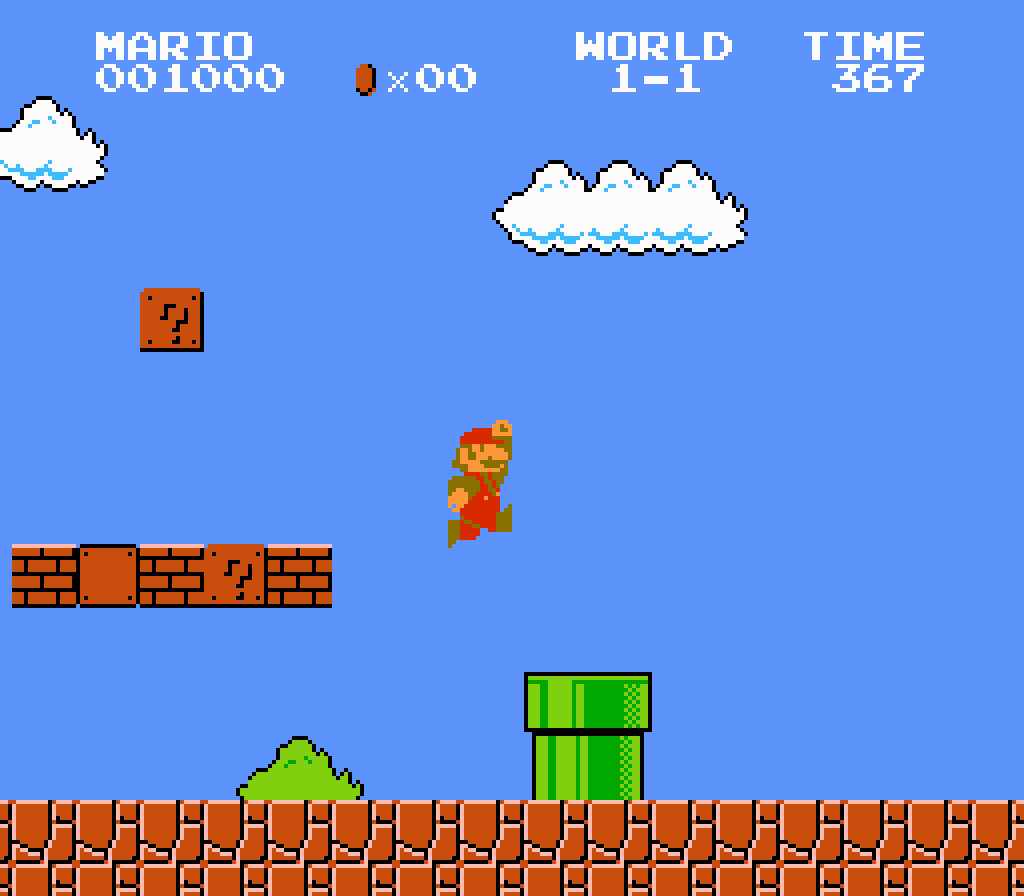

From as best I can tell, the cartridge version of both games are exactly the same, all the way down to the programming & data. This makes sense as there’s not really much that needs changing – there’s almost no text in the game, and there wasn’t really anything that needed to be censored or altered. However, I could be wrong about this, so if someone out there reads this and can correct me, please let me know!

So Many Versions

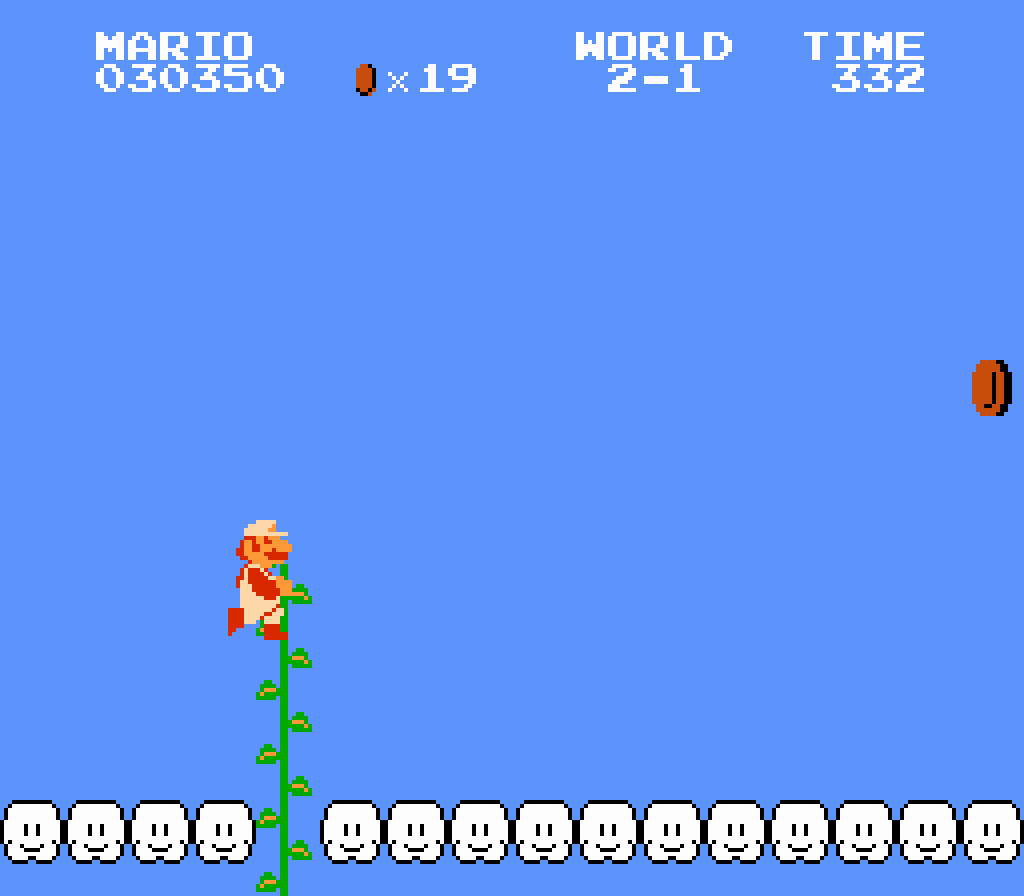

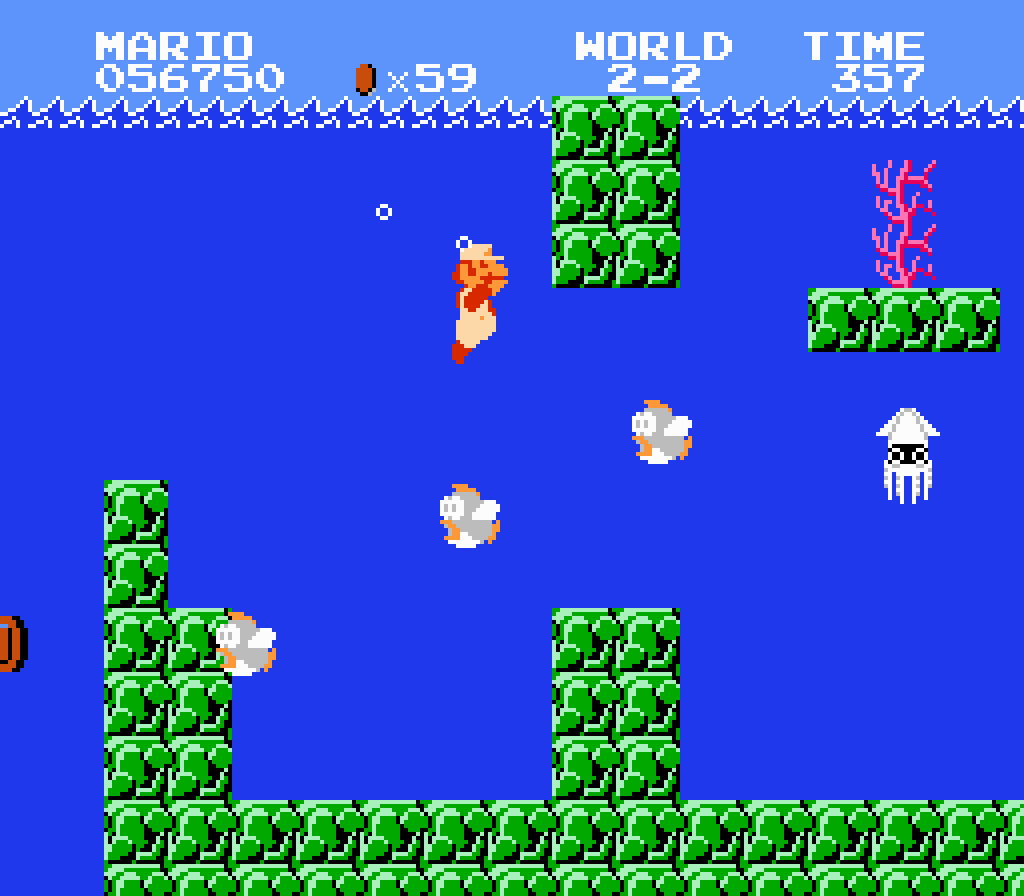

There are seriously like a dozen versions of Super Mario Bros. out there, so for sanity’s sake I’m only going to cover the standalone cartridge versions of both games. If you’re interested in seeing a bunch of the variations, though, don’t fret – I put up some quick screenshots and info here!

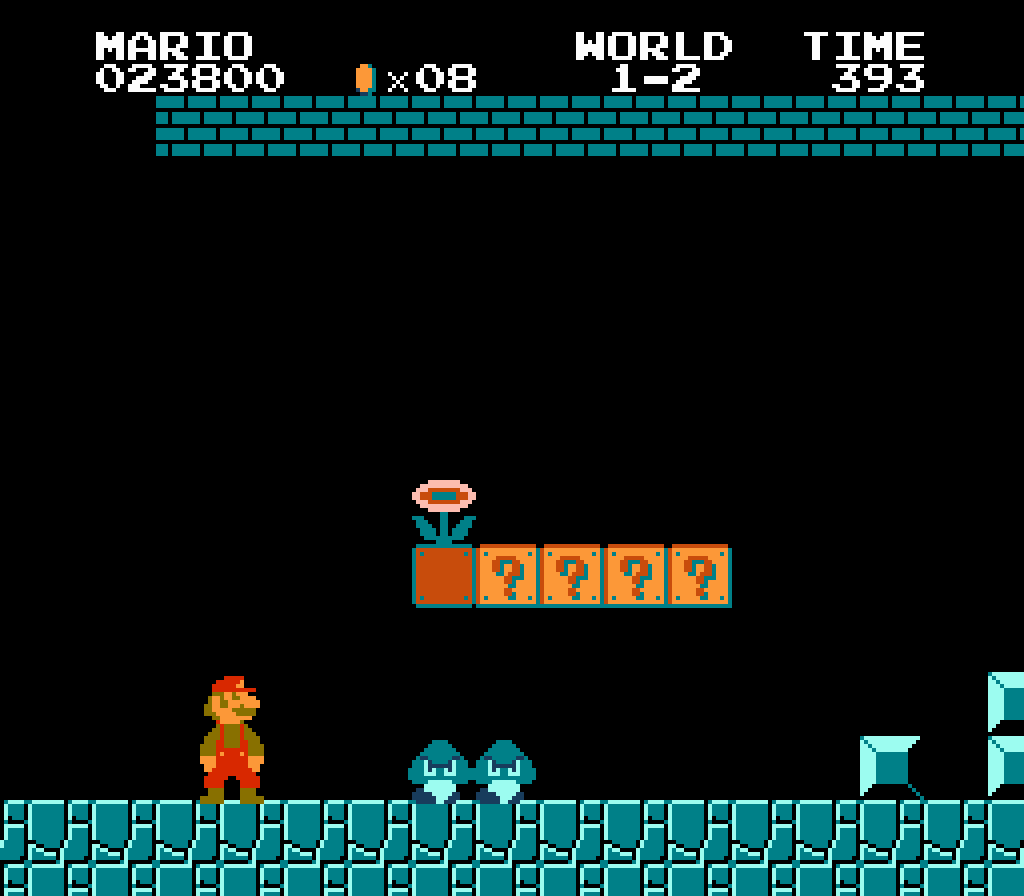

Why So Much English in this Japanese Game?

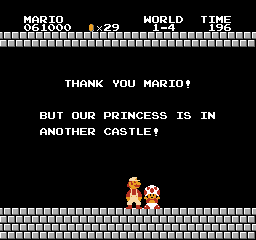

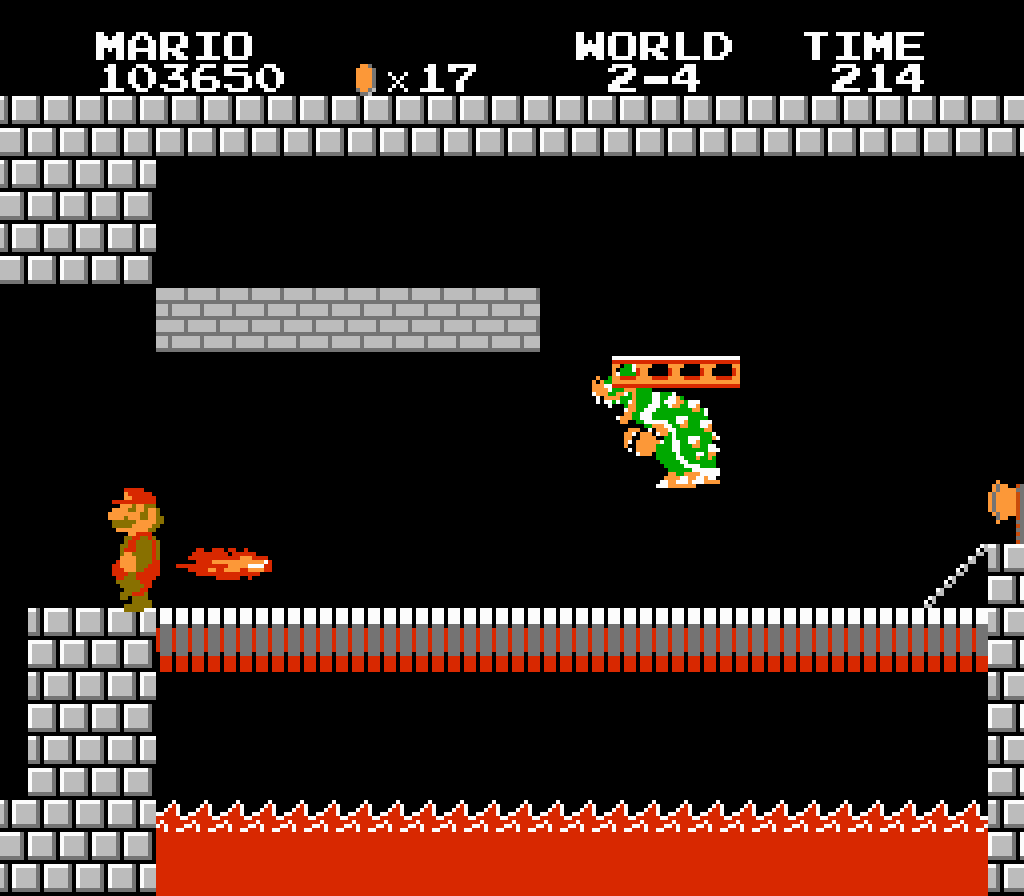

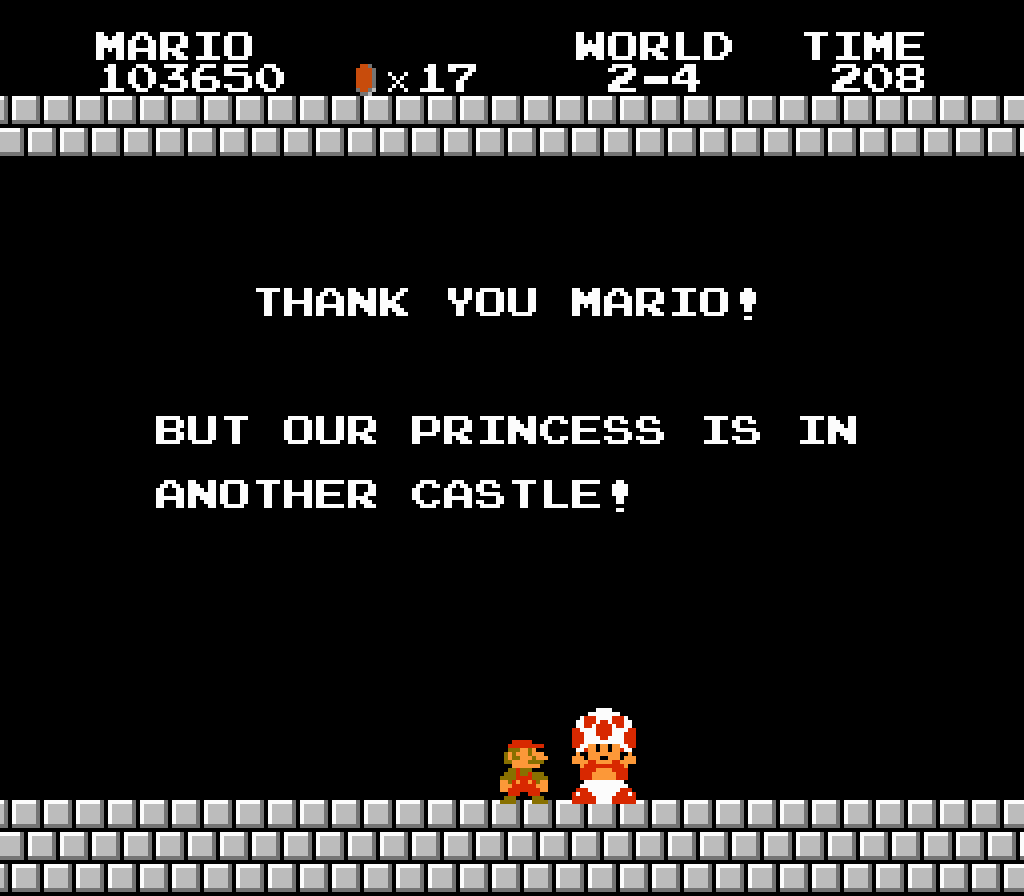

At the end of most of the castle levels, you end up saving one of the princess’ servants instead. In both games, the text says, in English, “Thank you Mario! But our princess is in another castle!”

|

It makes sense that this is in English in the North American version… but why is it in English in the Japanese version? That sort of question is something that I get asked a lot about Japanese games and such. There are a couple answers.

First, several years of English classes are required in Japanese schools. Granted, most of it is rote memorization that doesn’t really teach much of the language, but because of this, Japanese people at least know a lot of simple English phrases, nouns, and verbs.

Second, due to all sorts of political, socio-economical, and historical reasons, the Japanese language has absorbed lots and lots of English words. Even “Famicom” itself comes from the English words “family” and “computer”. In short, English is pervasive in modern Japanese, to the point that even people who never took the required English classes in school can rattle off a ton of English vocabulary.

Third, English is absolutely everywhere in Japan, so it isn’t really like some bizarre language. Just take a walk down any random street and you’ll probably find English all over. It’s also everywhere in print media, on TV, on clothes, food packaging… There’s no escape from it! Part of the reason for this is that English has a sort of “trendy” or “hip” vibe to it over there. It’s an interesting phenomenon, one that I’m sure many grad students have written about.

|

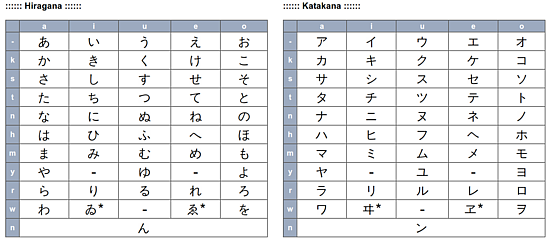

Fourth, back in the early days of gaming, programming limitations made it easier to just include the 26 uppercase letters of the English alphabet in games rather than the 100 or so Japanese kana characters. I’m guessing American computer designs and such played a big role too, but I don’t know enough about that to make any specific claims.

|

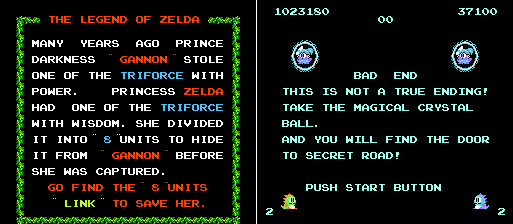

Because of this, many Japanese console games in the 80s had English-only text everywhere. Even if the text wasn’t even 100% understandable to players. It’s weird. You know how back in the day, we had poorly-translated games that often hardly made sense? This is kind of like the reverse of that, so when Japanese gamers think of retro games, one thing they think of is games where all the text is in blocky uppercase English letters rather than Japanese.

|

All of this is a very quick, simplified explanation, of course.

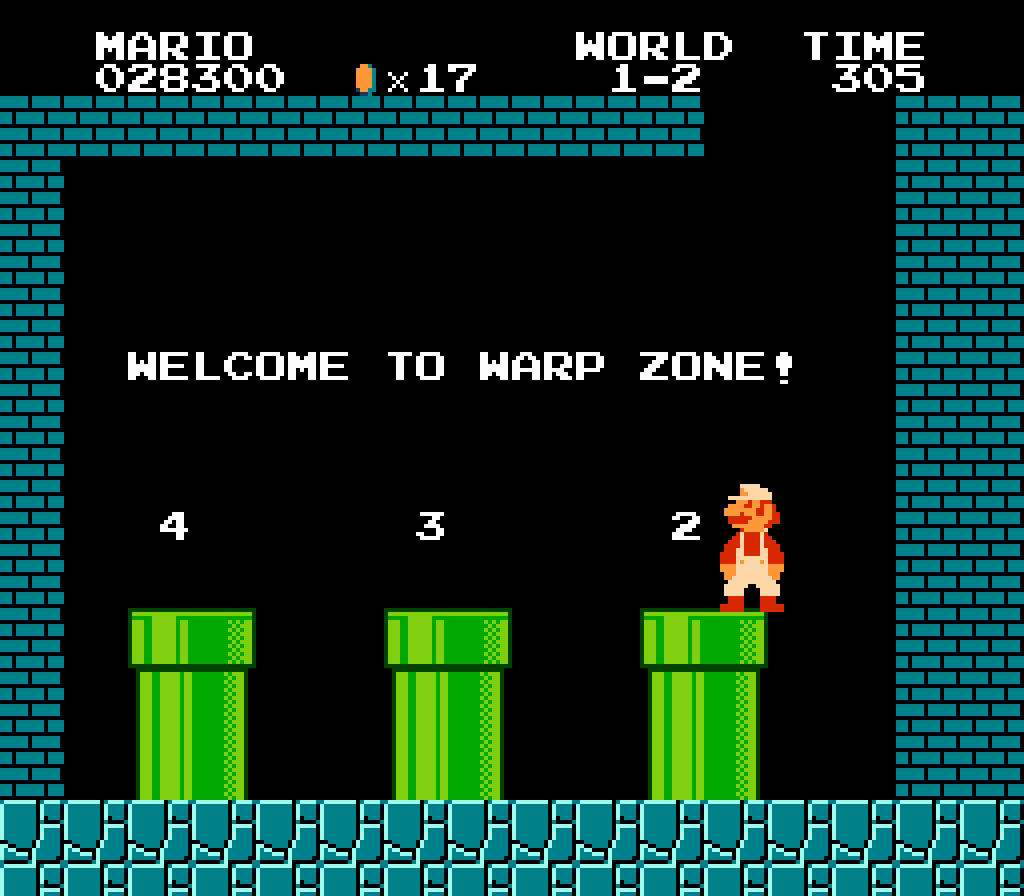

Rescue Message

Similar to the above, the text displayed when you beat the game and save the princess is the same in both games.

The interesting question about this is: how many Japanese players didn’t understand this? English is my native language, and the line “Push button B to select a world.” seems kind of odd even to me – it sounds like she wants you to press B right now, but doing so will only take you back to the title screen instead. You actually have to press the B Button at the title screen to change stages. It’s not completely clear in English, so I wonder how many Japanese players missed what it was trying to say.

|

No Comments