The heroes head to the underground Tower of Babil in an attempt to steal back all of Golbez’s crystals.

Tower of Bab-il’s Name

The Tower of Babil’s name has been surprisingly difficult for Japanese-to-English translators over the years. In Final Fantasy IV, I mean. Sorry if you’re finding this page while looking up Bible stuff.

Some background info: the Tower of Babil is a giant, ancient, and mysterious tower in Final Fantasy IV that’s rooted deep underground and stretches far aboveground, into the sky. As such, it’s relatively clear that the name is meant to allude to the Tower of Babel that’s referenced in the Bible and elsewhere.

There’s a problem, though – in Japanese translations of the Bible, “Babel” is usually written as バベル (baberu), but the tower goes by a slightly different name in every Japanese version of Final Fantasy IV: バブイル (babuiru). This babuiru name can be spelled in English in many different ways, such as “Babuiru”, “Babuil”, “Babuir”, and so on. This spelling uncertainty meant that translators had to pick a name and hope it was what was intended.

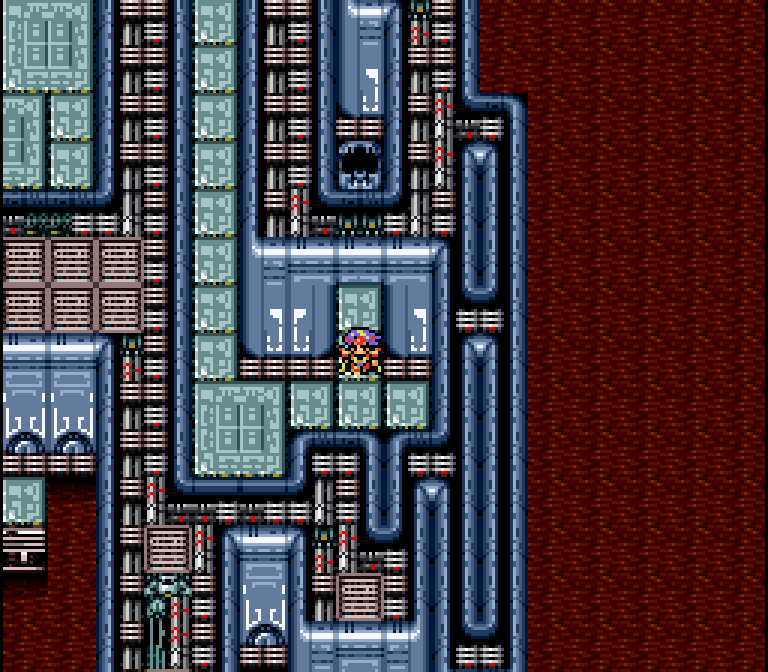

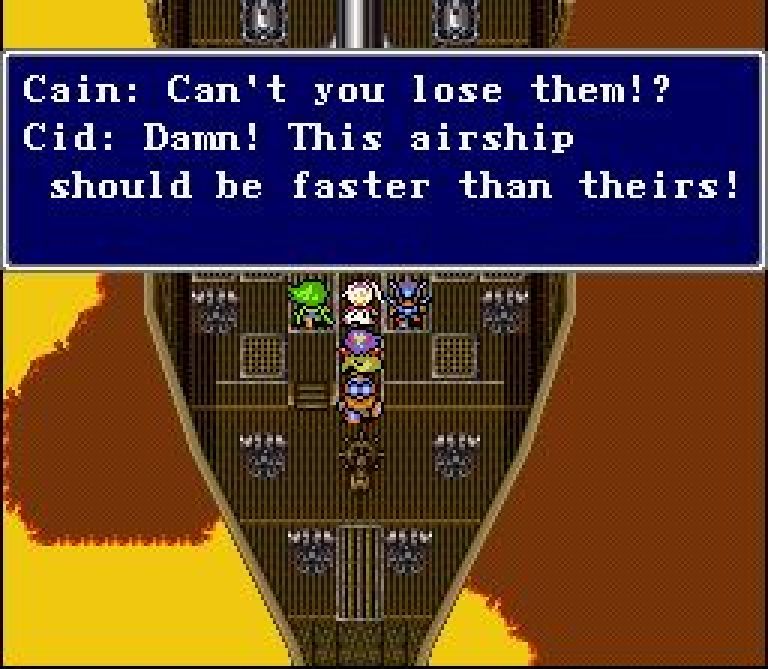

In the original Super NES English translation, the tower was called the “Tower of Bab-il”:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

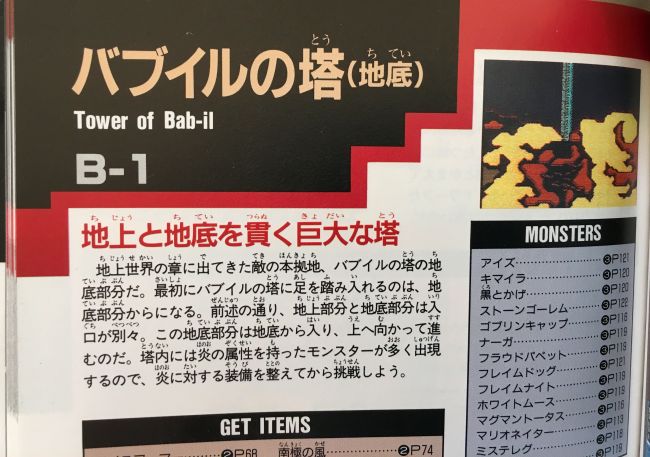

Incidentally, an official Japanese guide also uses the “Bab-il” spelling:

This was published one month before the English translation was released, though, so it’s hard to say if the guide simply pulled from the English translation or the other way around.

Next, when the game was re-translated for the PlayStation, the name transformed into “Tower of Babil”:

A few years later, the tower was renamed to the “Babel Tower” in the Game Boy Advance translation:

A few years after that, the tower went back to being the “Tower of Babil” in the DS translation:

And after that, the tower remained the “Tower of Babil” in the PSP translation.

So which name is correct? Again, it’s hard to say, but from what I’ve read from Japanese sources, the name バブイル (babuiru) is actually taken from the Assyro-Babylonian myth of a giant tower, and that the name means “Gate of the Gods”. It sounds like the Biblical story about the Tower of Babel was likely based on this ancient myth, but I’m not an expert in Biblical history or ancient mythology, so I make no claims about its veracity. Still, this sort of thing crops up often whenever I’m translating ancient and foreign religious names from Japanese to English, so it makes some sense to me.

Personally, I kind of like how unusual the original translation’s “Bab-il” choice looks, but for simplicity’s sake I’ll just continue to call it “Babil” in my analyses.

Layout Changes

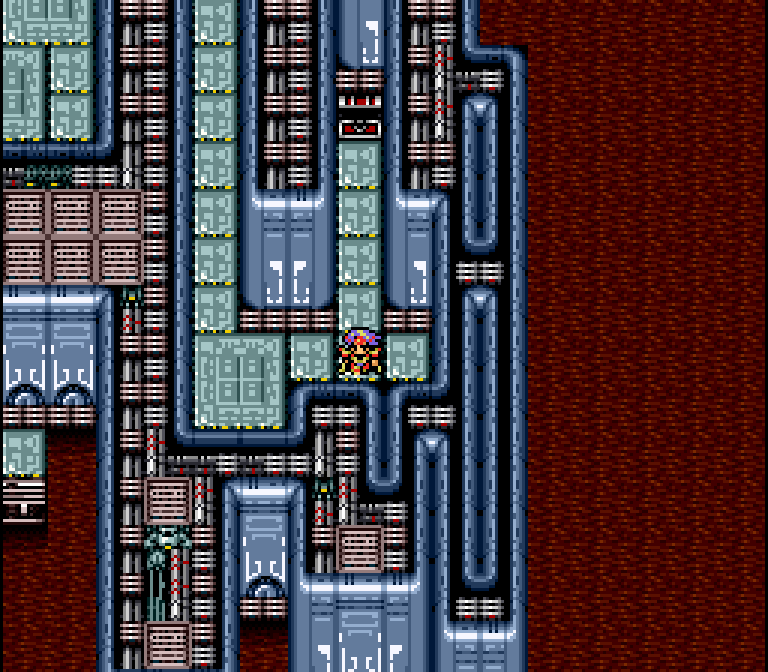

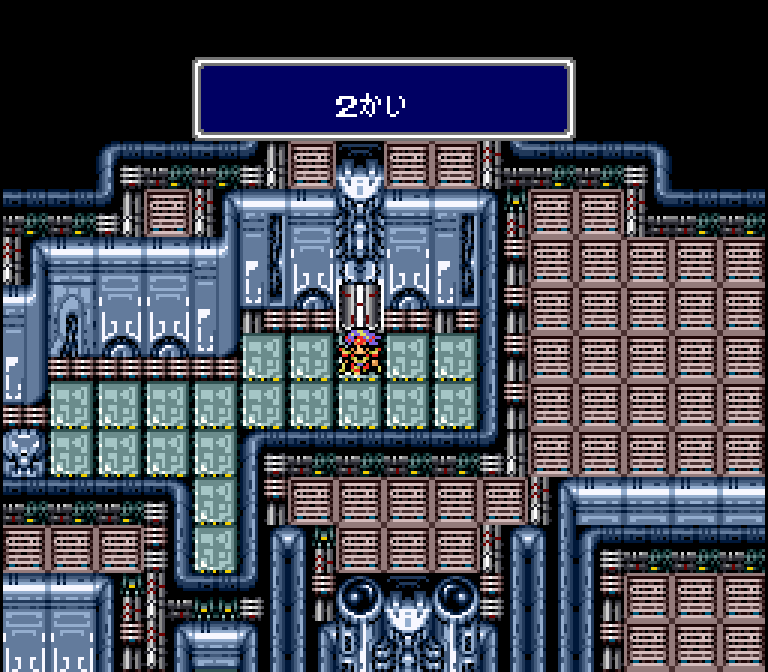

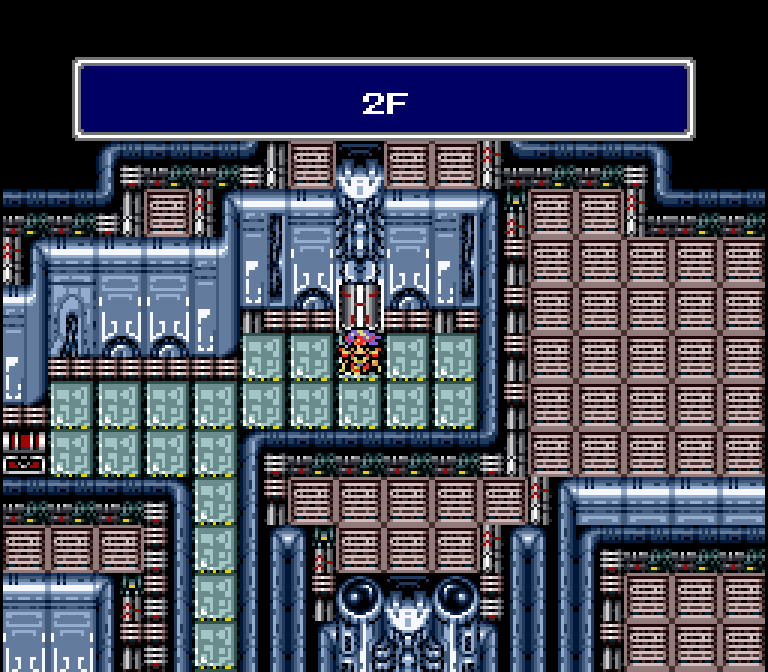

As we’ve already seen, the tower areas are slightly tricky to navigate in the original Final Fantasy IV – certain areas are covered with foreground tiles that look like impassable walls but aren’t actually obstacles:

|  |  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy IV Easy Type (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

In the example above, we see how the designers purposely used these fake walls to hide things from players. These fake obstacles were removed from the Easy Type and English releases to help players traverse the towers.

Similarly, we’ve already seen how the tower treasure chests were redesigned to stand out more in the Easy Type and English releases:

|  |  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy IV Easy Type (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

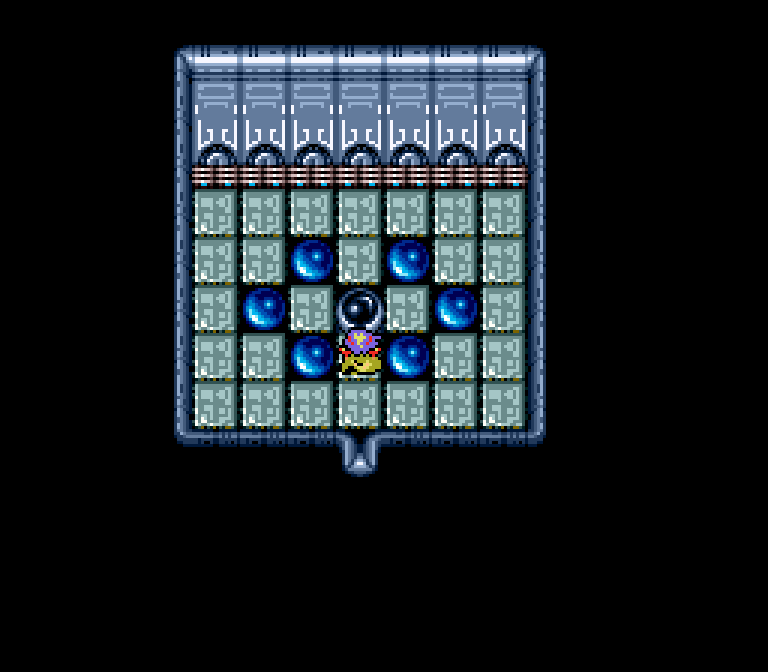

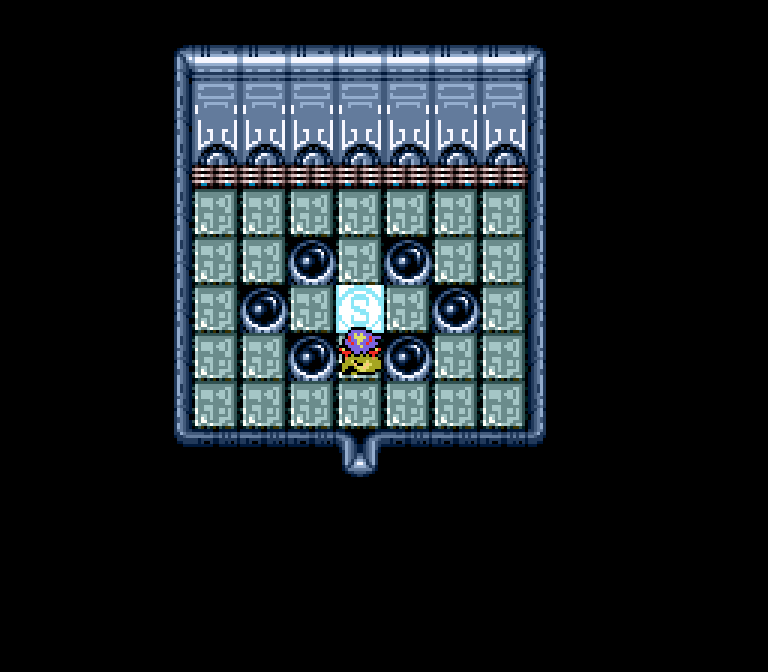

And, just like in the Tower of Zot, the animated glowing orbs were replaced with static orbs in the Easy Type and English versions:

|  |  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy IV Easy Type (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

Treasure Changes

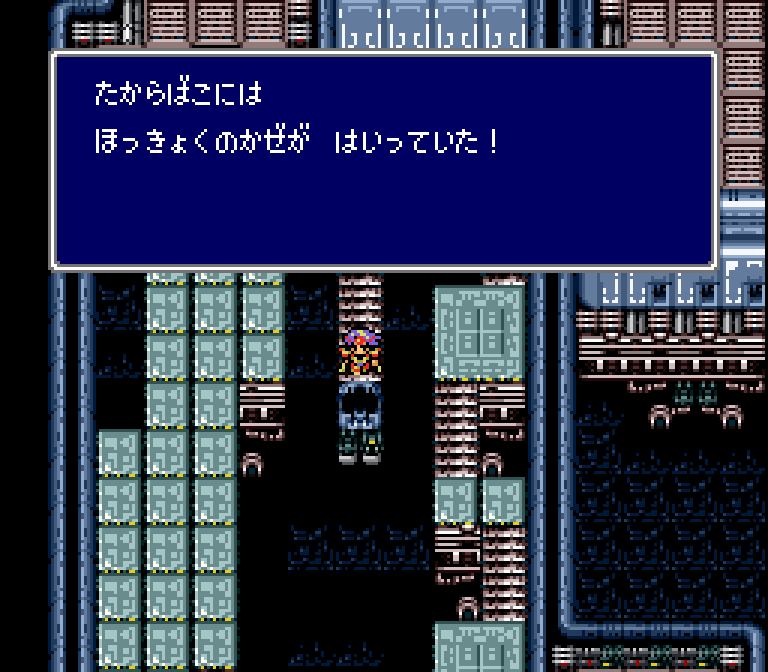

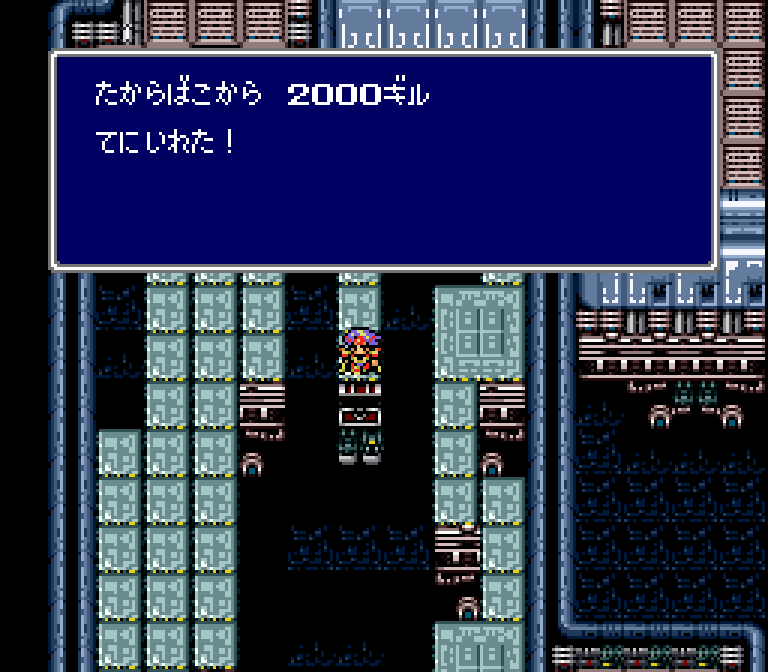

A few treasure chests in the tower had their contents changed from the original Final Fantasy IV:

|  |  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy IV Easy Type (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Location: | Final Fantasy IV | Final Fantasy IV Easy Type | Final Fantasy II |

| 4th Floor | Antarctic Wind | Revive Medicine | Life |

| 5th Floor | Arctic Wind | 2000 Gil | 2000 GP |

By this point in the game, the Arctic and Antarctic Wind items are probably not very useful anymore. Then again, a Life potion and 2000 GP aren’t especially useful at this point either.

Item Name Changes

As seen before, item names with an English-language flair in the original version were rephrased to use Japanese terms for the Easy Type release. This was done to ensure that Japanese players with limited English knowledge – particularly younger players – could fully understand the implications of each item name.

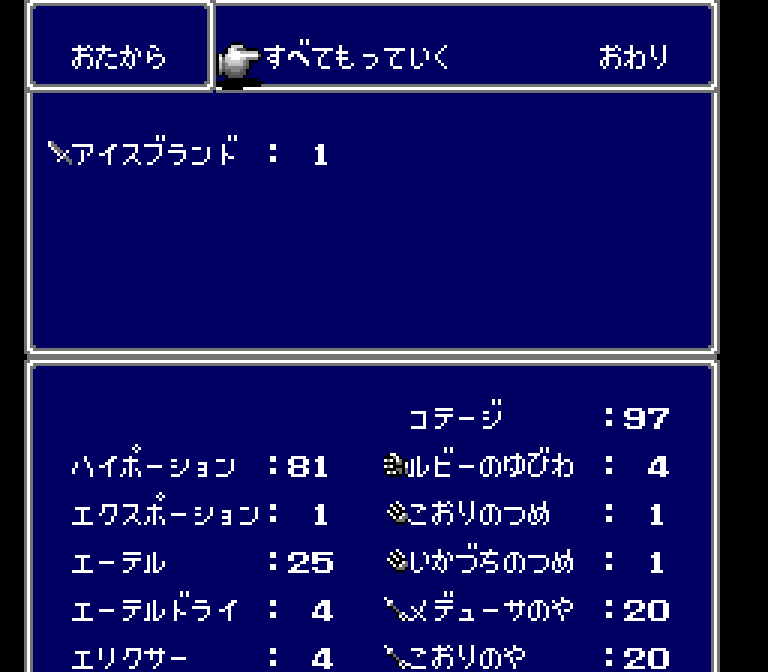

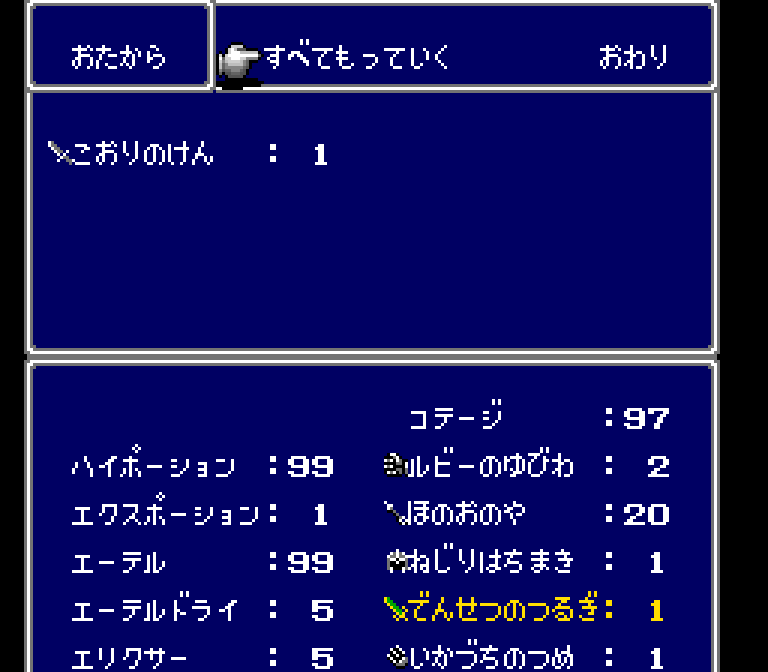

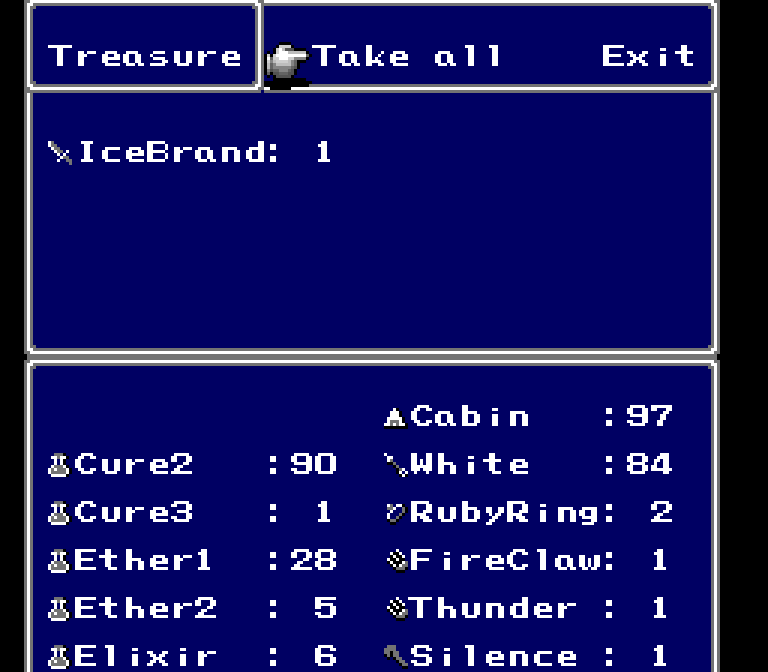

Here’s an interesting example of those name changes in action:

|  |  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy IV Easy Type (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

- First, this sword found in the Tower of Babil is called the アイスブランド (aisu burando) in the original Japanese release of Final Fantasy IV, and is basically how you’d pronounce the English phrase “Ice Brand” in Japanese.

- This “Ice Brand” name was replaced with こおりのけん (kōri no ken, "ice sword") for the Easy Type release.

- Yet, we see that the name in the English release is “Ice Brand”, making it identical to the name in the original Japanese release.

This is another indication that the English release isn’t based on the Easy Type version, as is often claimed on some fan sites. Instead, I believe both were developed in parallel rather than sequentially.

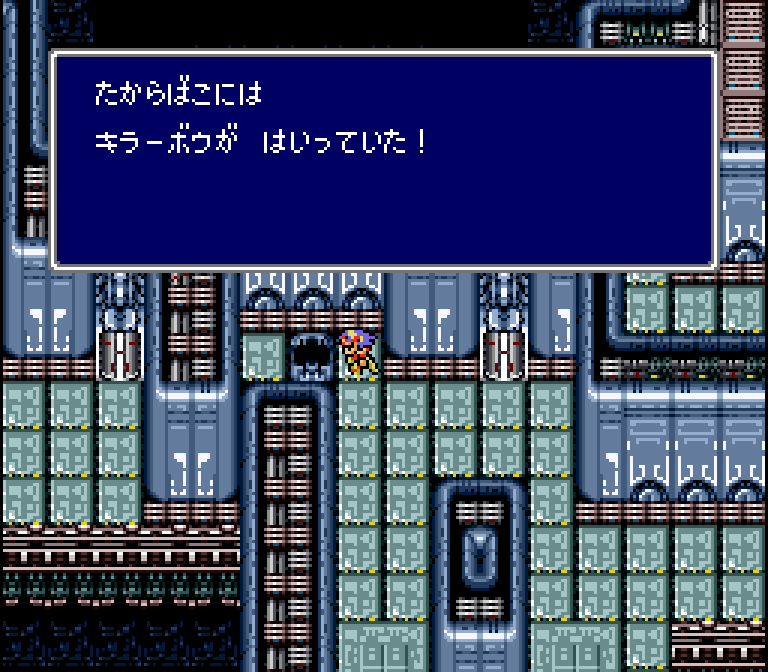

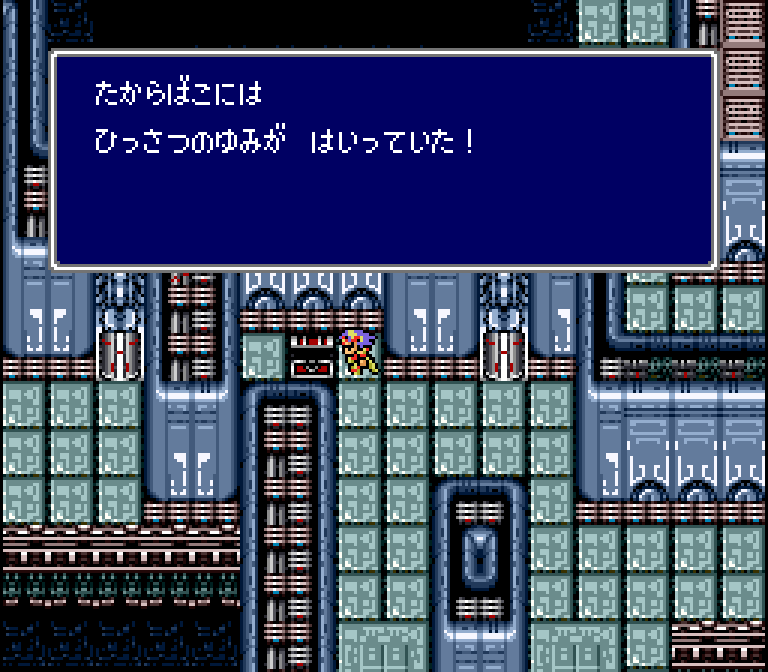

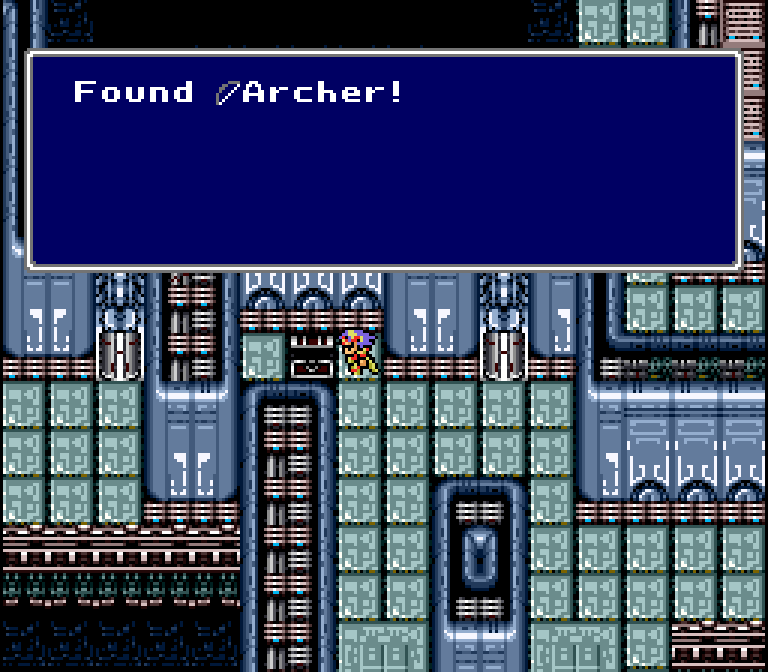

A bow weapon found in the Tower of Babil offers another interesting example of this item name strangeness:

|  |  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy IV Easy Type (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

Here, we can see how the キラーボウ (kirā bō, "killer bow") item from the original release was renamed the ひっさつのゆみ (hissatsu no yumi, "sure-kill bow") for the Easy Type release. But the item was completely renamed the “Archer Bow” in the English release, most likely because of Nintendo’s old rules against references to violence and killing.

Dr. Lugae’s Name

The heroes encounter a mad scientist in the tower. In Japanese, his name is ルゲイエ, which is pretty unusual and can be written in English a dozen different ways, including “Lugeie” and “Rugeie”. Despite this unusual name, he’s known as “Lugae” in every English release of Final Fantasy IV. This unusual name consistency across 20+ years of Final Fantasy IV translations is surprising, so I always wondered if he was named after someone or something.

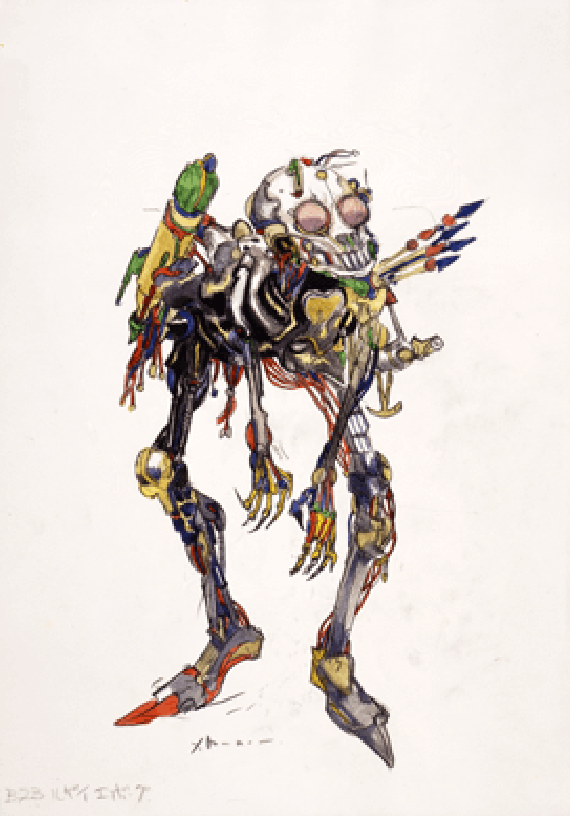

Incidentally, when Lugae transforms, his name remains as “Lugae” in the games, but it seems the developers referred to him as “Lugaeborg” before the game was released. The name appeared in an early official strategy guide, and it even appears in the character’s official concept art:

This “Lugaeborg” name has led some Japanese fans to surmise that the name originally comes from Gáe Bulg with the “le” article preceding it. I don’t know if the theory is correct or not, but I feel it’s within the realm of possibility. Translating names between Japanese and English is usually pretty messy to begin with, so when you introduce another language into the mix (especially an ancient one), those already-messy naming patterns go out the window.

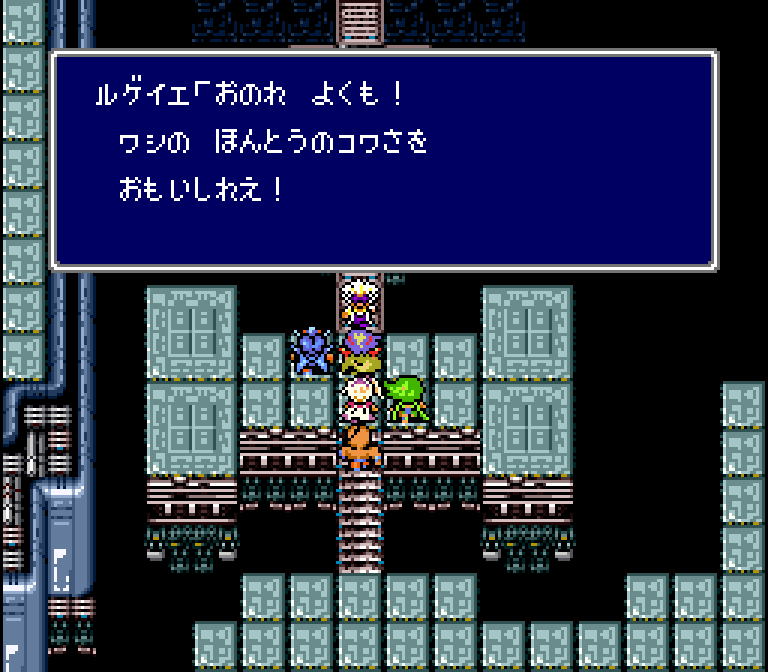

Meeting Dr. Lugae

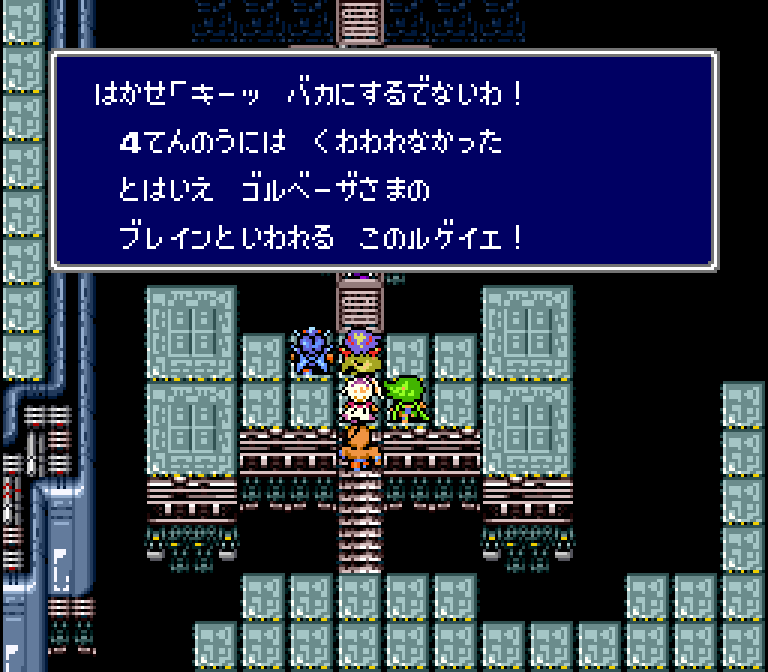

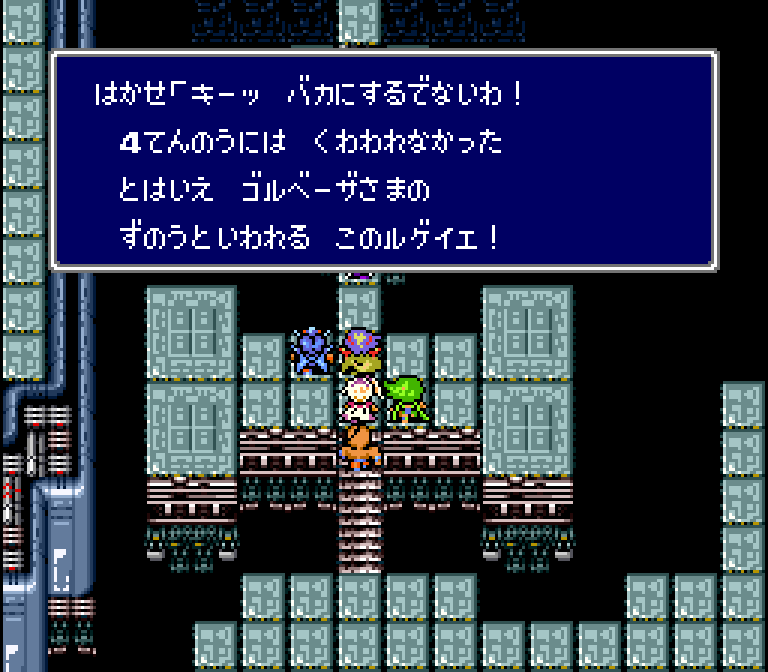

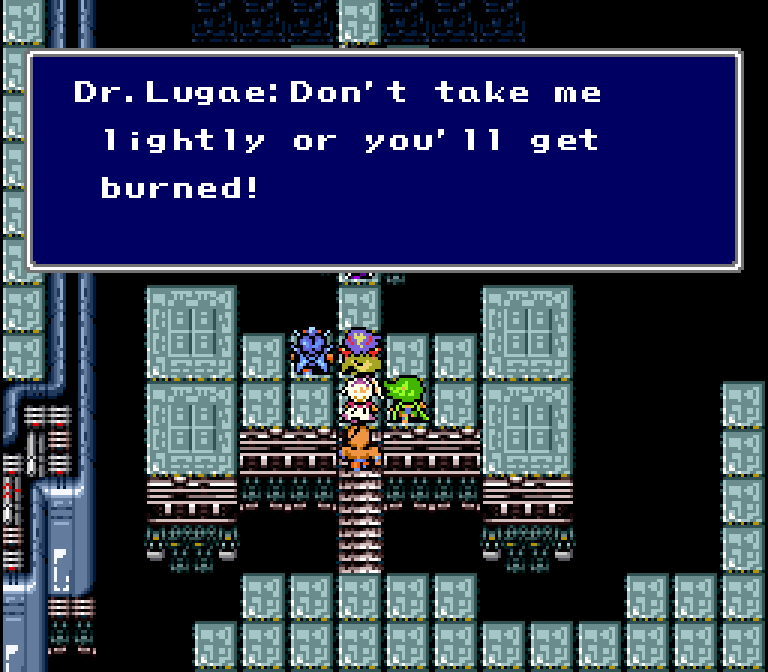

Dr. Lugae feels insulted when the heroes talk down to him. Part of his response was shortened quite a bit in translation:

|  |  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy IV Easy Type (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Keee! Don’t you dare you mock me! Although I didn’t get to be one of the Four Heavenly Kings, I, Lugae, am known as Lord Golbeza’s “brain”! | Don’t take me lightly or you’ll get burned! |

The shortened text was likely due to memory restraints, but I actually like how short and snappy the English version is. Unfortunately, it drops some of the character’s background information that actually sounds intriguing to me as a fan. It’s a shame we don’t really learn much more about him than what’s said during this scene.

In any case, the Easy Type version of the game also features a text difference. The original Japanese script uses the English word “brain”, but the Easy Type script instead uses the Japanese word for “brain”. This was done to make the intended meaning clearer for Easy Type players.

Lugae Transforms

The ensuing fight with Lugae actually consists of two separate battles. First, he commands his hulky robot to attack the party. His dialogue here is marginally different in translation due to text length limitations:

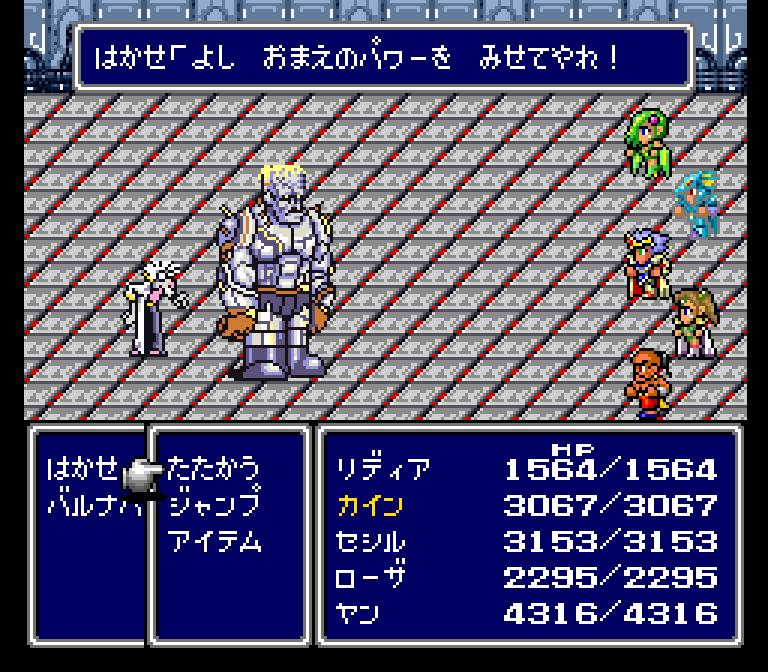

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Version |

| Doctor: Okay! Show them your power! | Dr.: Beat them up! |

Similarly, his next line was also shortened and simplified in the Super NES release:

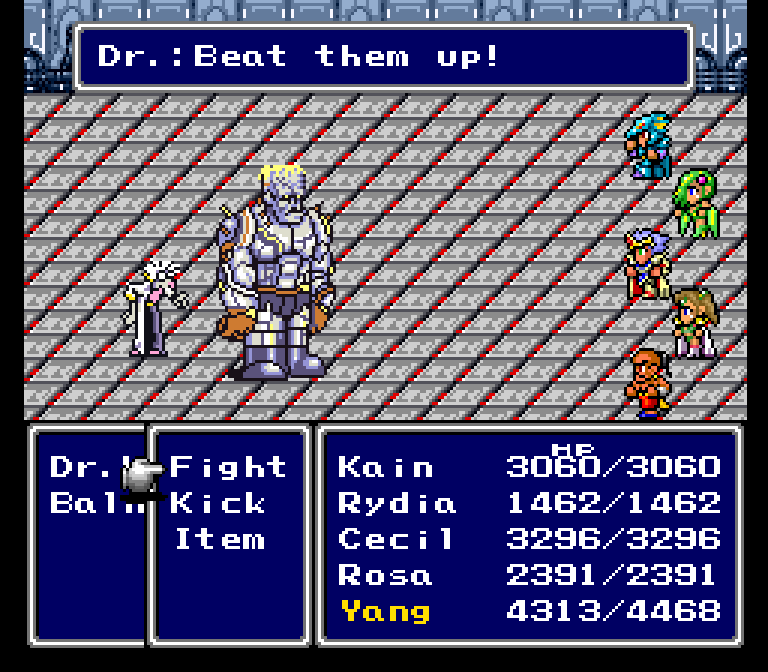

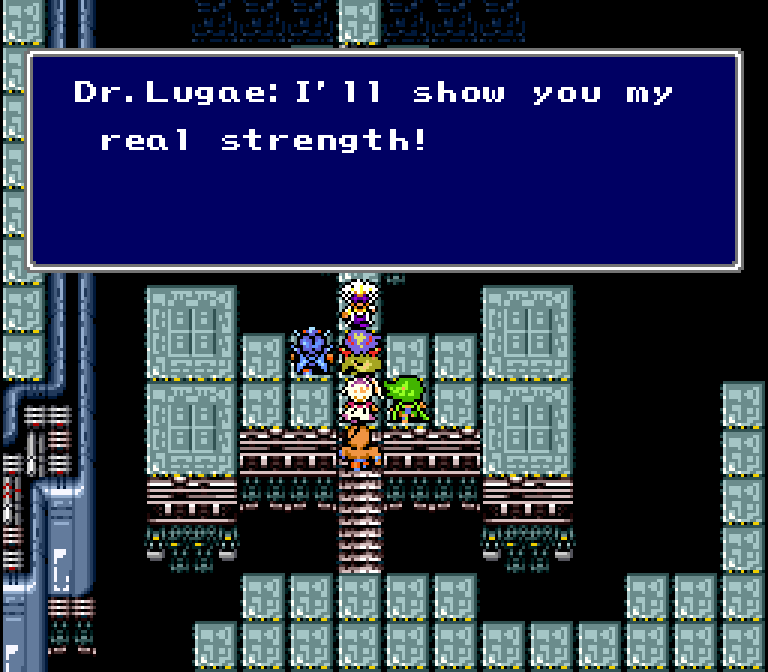

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| How dare you! Now you will learn what true terror is! | I’ll show you my real strength! |

At this point, Lugae transforms into a horrific skeleton-like creature. His pre-transformation dialogue is a little more threatening in Japanese, but I do like the simple, confident-sounding line in the translation:

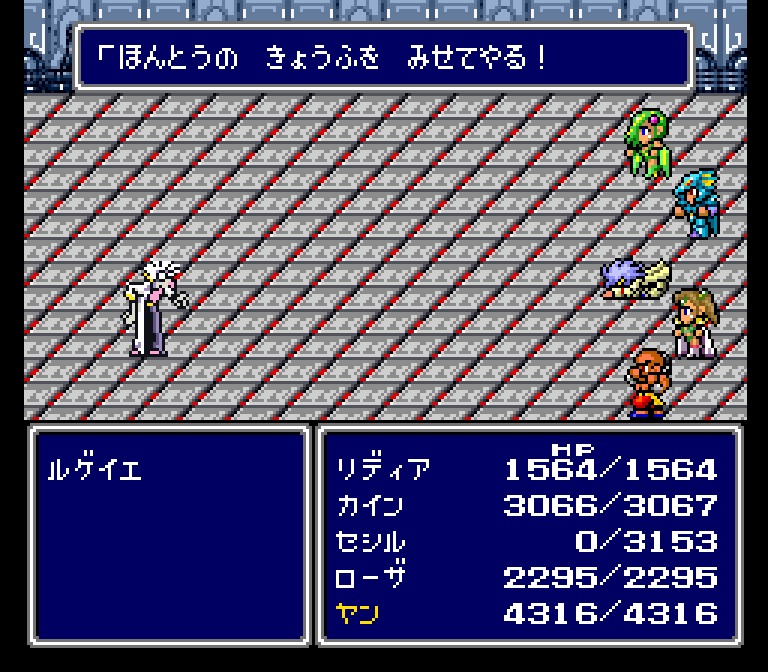

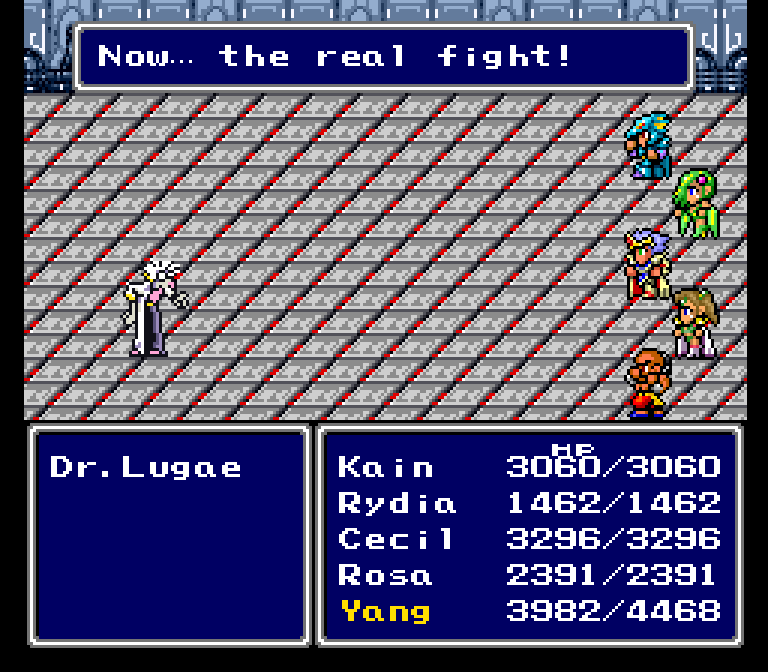

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Now I’ll show you true horror! | Now… the real fight! |

These differences are all very minor, but if you string each line together, he does sound more menacing – and motivated – in Japanese.

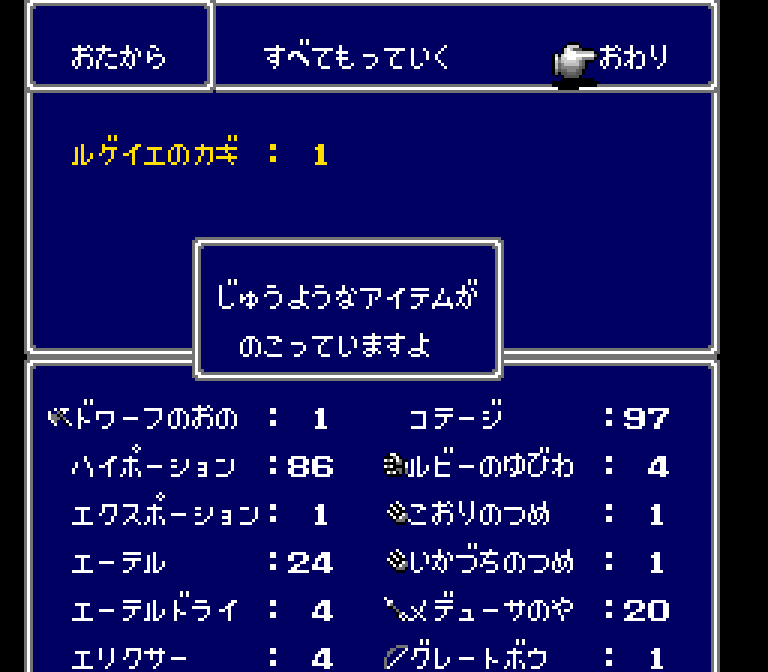

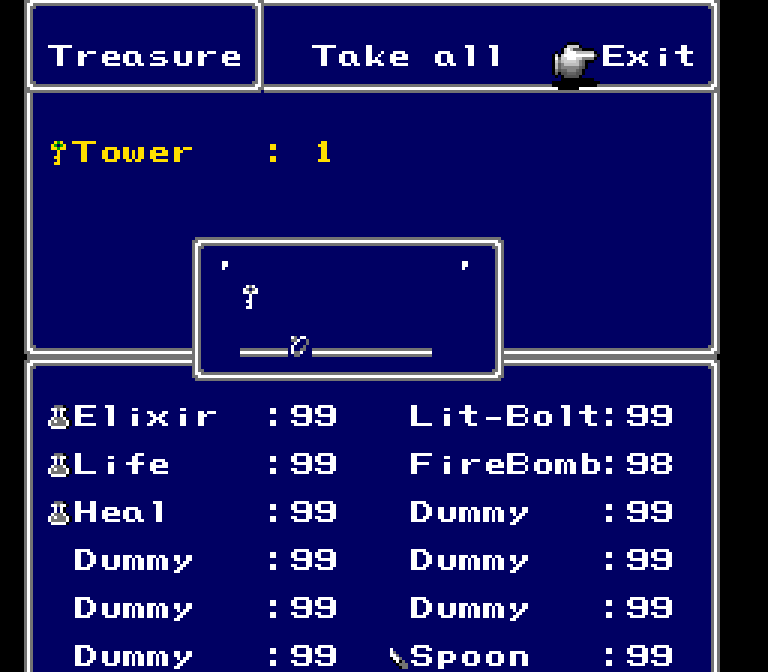

Tower Key / Lugae’s Key

Lugae drops a key item after he’s defeated. In Japanese, it’s called “Lugae’s Key”. In the Super NES translation, it’s simply called the “Tower Key”:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

What is surprising, though, is what happens if you refuse to accept the key. In the Japanese releases, an error message pops up with text along the lines of “Hey, you’ve left an important item behind.”

The English translation also generates an error message – but the message was left untranslated. As a result, the error message is a bunch of meaningless nonsense. Perhaps by sheer luck, the garbled message includes a key icon, which is probably enough for players to surmise what the message is about. This is a perfect example of how rarely seen video game text can sometimes slip through the localization process.

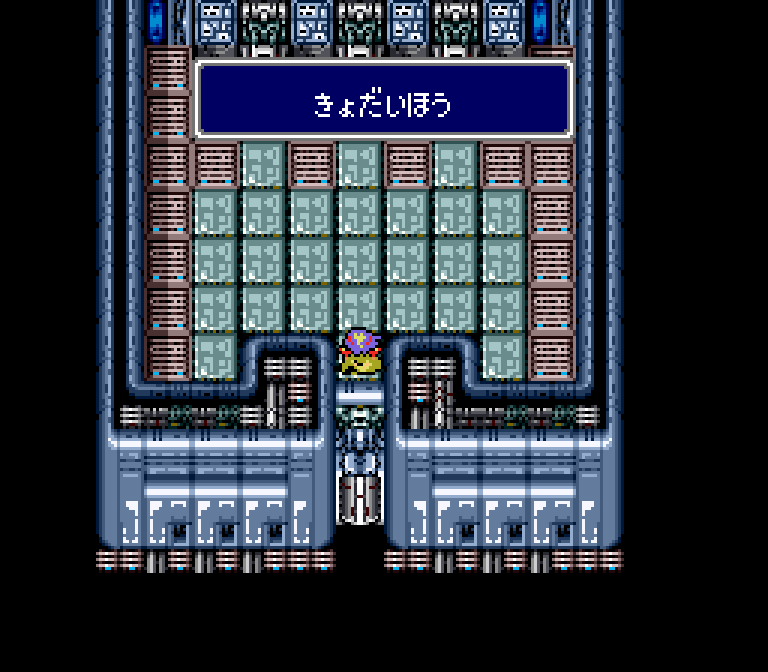

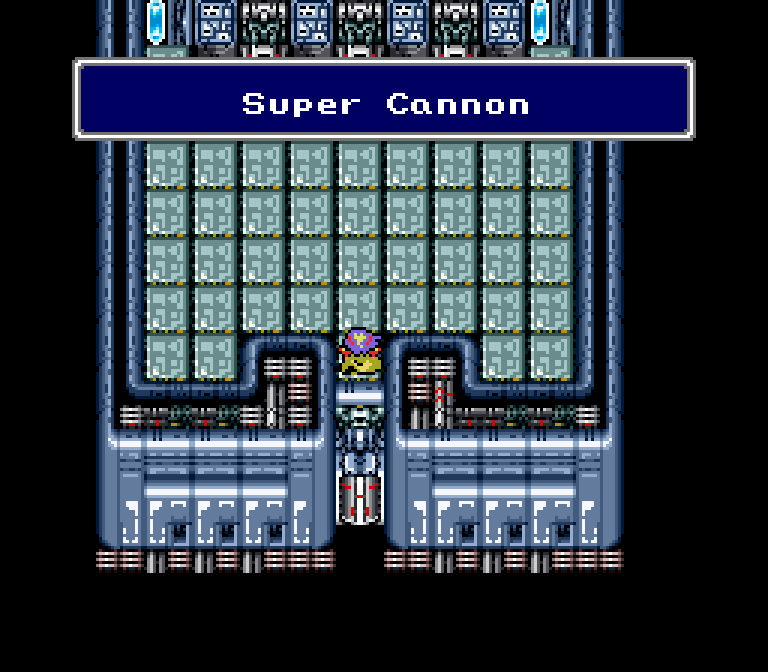

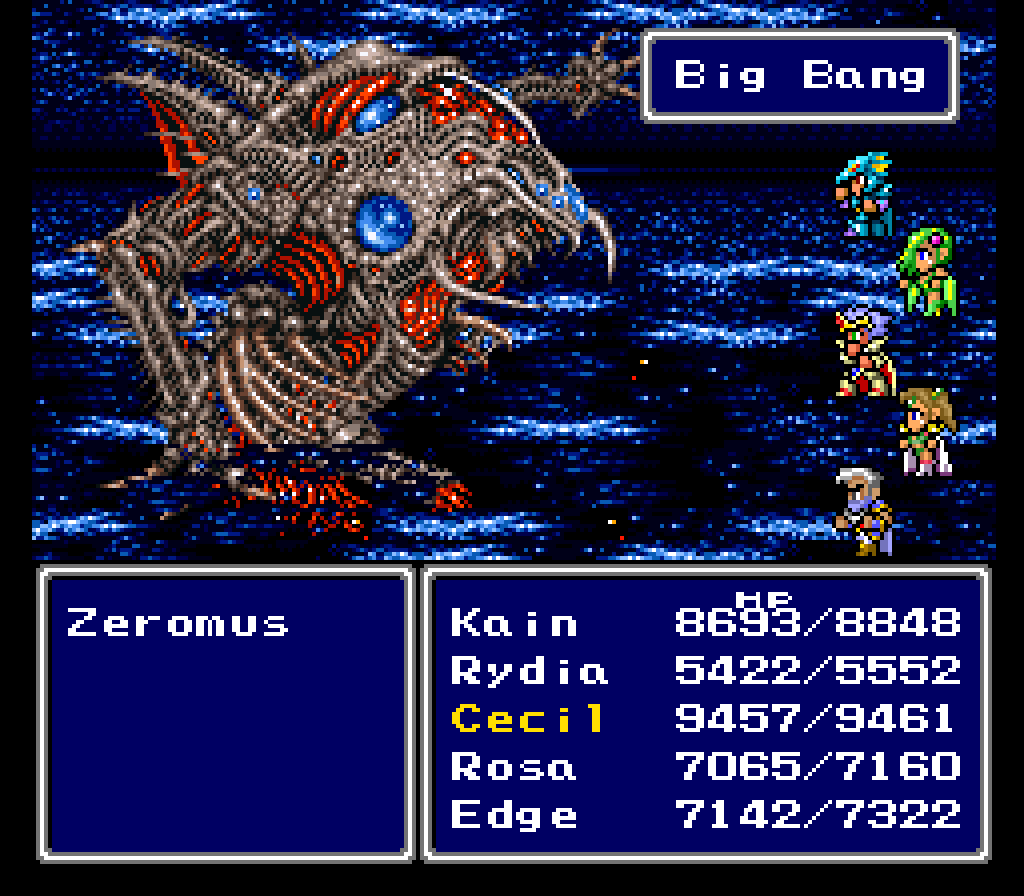

Super Cannon / Giant Cannon

The bad guys are using the Tower of Babil to bombard the dwarves, so the heroes try to stop the bombardment while inside the tower:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

In Japanese, the cannon is simply called the “Giant Cannon” (“giant” as in “huge”, not the race/species or the robot later in the game). In English, it’s given a more unique name: the “Super Cannon”.

When the heroes enter the cannon room, however, there are three bad guys operating some sort of machinery or panels. This, plus the fact that the Japanese language doesn’t automatically differentiate between singular and plural nouns, suggests that there might actually be more than one cannon. As far as I know, it’s never made clear how many cannons there actually are, so it’s possible that “Super Cannon” should be “Super Cannons”.

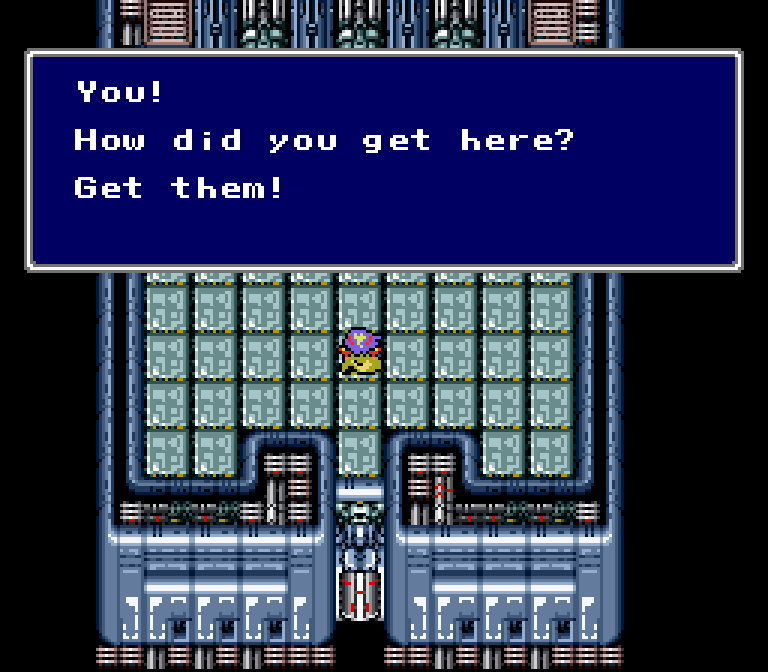

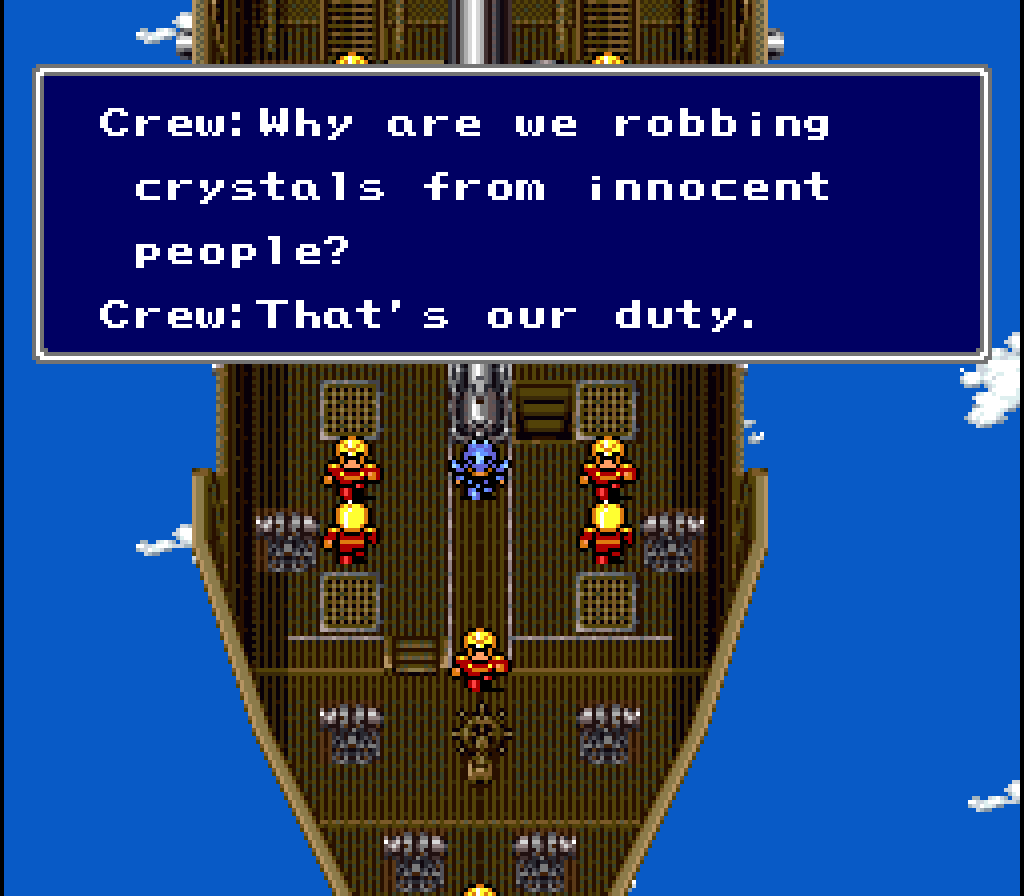

Translation “Clumping”

When the heroes enter the cannon room, three lines of enemy dialogue pop up. In Japanese, the punctuation makes it immediately clear that three different characters are speaking. In the English release, that fact isn’t nearly as clear:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

We continue to see this “three people are talking but they only sound like one person in the English translation” phenomenon in Square’s old games. We’ve seen it several times in Final Fantasy IV by now, and I know it occurs in Final Fantasy VI too. This “clumping” phenomenon is interesting to me, so maybe someday I’ll look for more examples.

I guess the lesson here is that how translated text is presented can sometimes be just as important as what the translated text says.

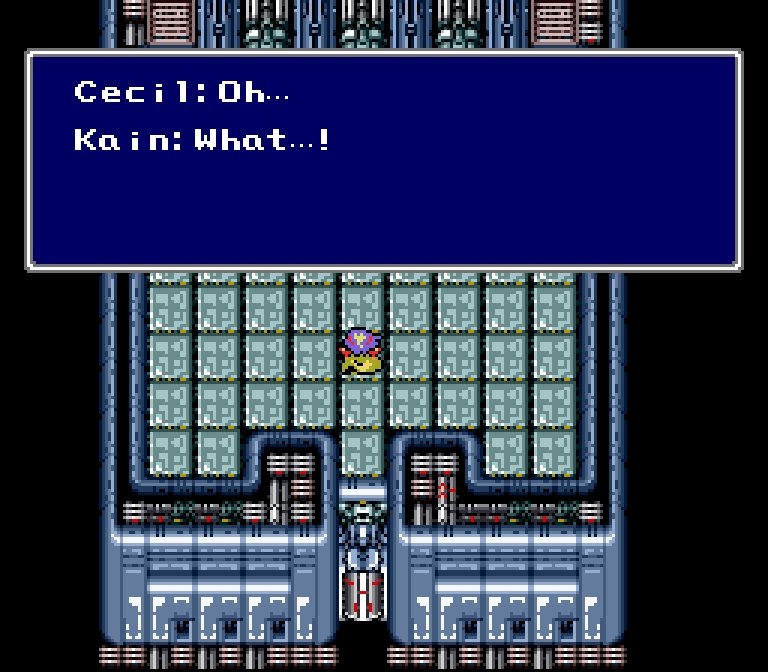

Cecil responds when he sees the bad guys in the cannon room:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

In Japanese, he says something along the lines of “Oh, no!”, “Not good!”, or “Crap!”. Basically, it’s an emphatic phrase of undesirable surprise. In the English translation, his shock transformed into the meek-sounding “Oh…” This minor difference falls in line with other translation choices we’ve seen so far in the game.

Yang’s Sacrifice

The bad guys wreck the cannon’s controls and cause it to overload. Yang kicks everyone out of the room and sacrifices himself to save them from the explosion. In reponse to being kicked out of the room, Cecil shouts at Yang:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Cecil: Yang! | Cecil: Yang!! Open the door!! |

It’s a minor change, but it’s surprising to see that text was added to the translation after seeing text getting cut left and right throughout the game so far. Even the use of extra exclamation marks is a little out of character with the rest of the game’s translation. Perhaps this scene was given a little extra editing work than most of the other parts of the script.

Golbez’s Idiom

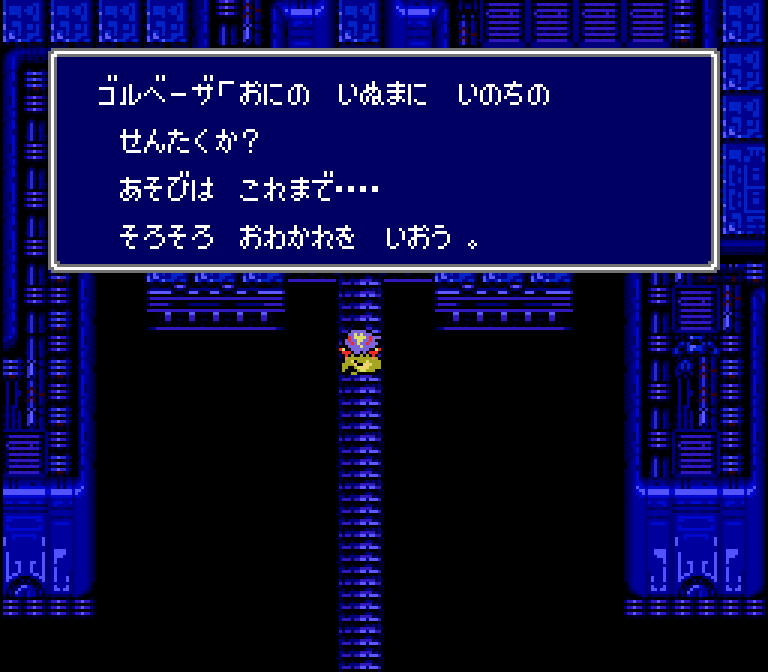

Just as the heroes leave the tower, Golbez’s voice booms from out of nowhere. He taunts the heroes and then attempts to kill them once and for all.

His taunt in Japanese is a variation of an idiom that doesn’t work well in a literal translation: oni no inu ma ni inochi no sentaku ("Refreshing your life while the devil is away"). Functionally, however, it’s similar to an idiom we have in English about cats and mice. With that in mind, here’s what this particular scene looks like in Japanese and English:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| When the cat’s away, the mice will play, I see. | This is all for play, kids. |

| Playtime is over… I now bid you farewell. | ……Farewell…! |

This Japanese idiom was consistently replaced with the cat-and-mice English idiom in every English translation of the game after the Super NES release. It’s rare when idioms between two languages have strong counterparts, so it’s cool to see how well this one fits this situation.

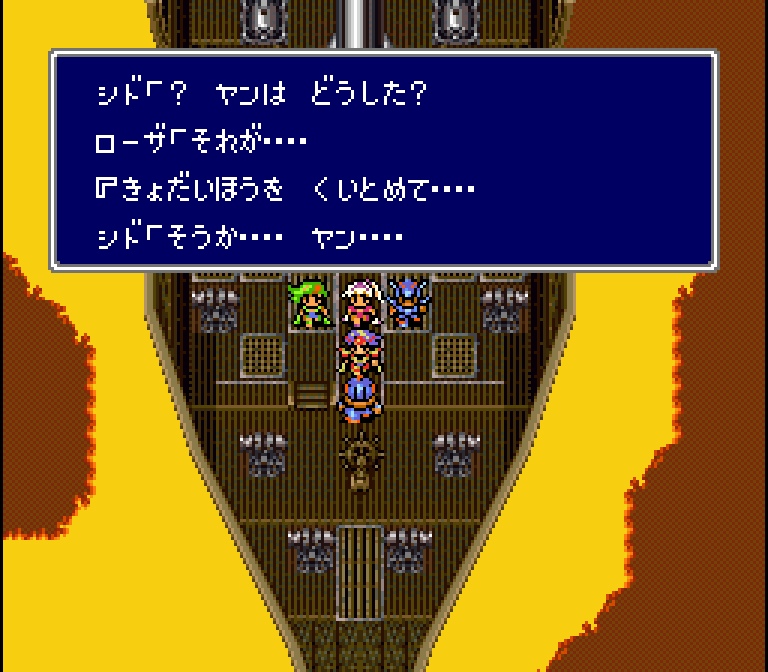

Cid’s Rescue

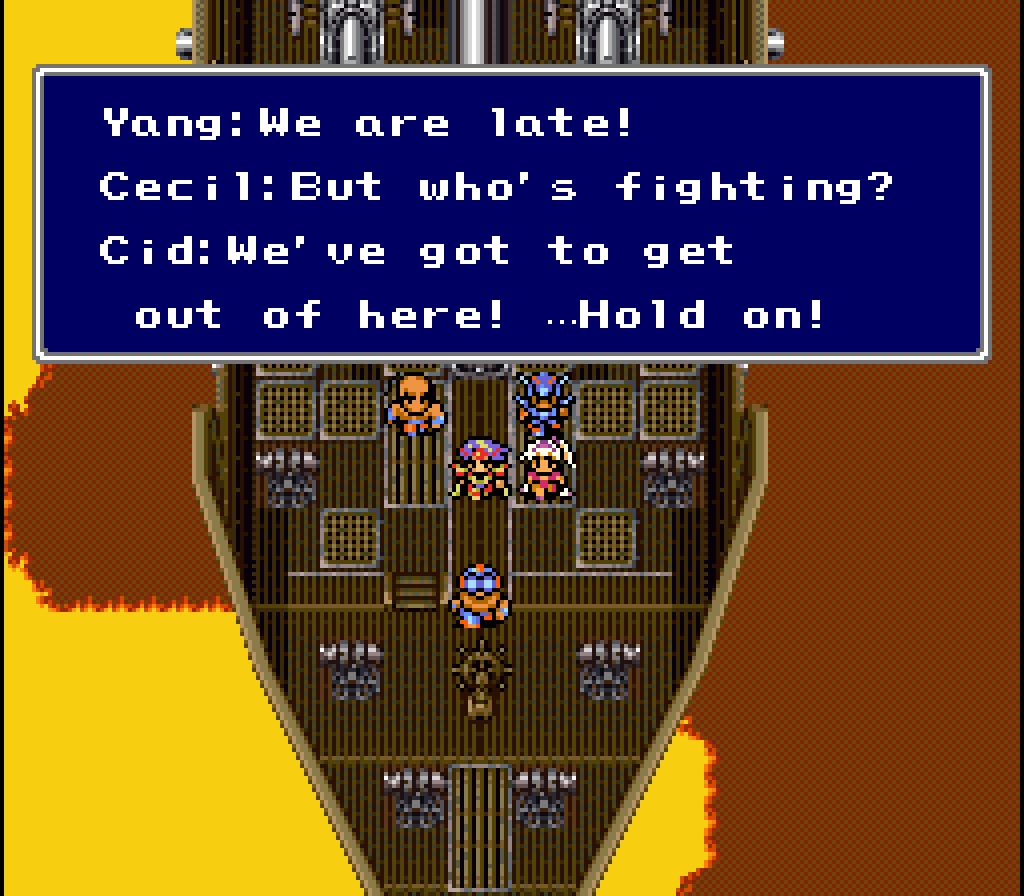

The heroes plummet to their doom… until Cid saves them with his airship at the last second. Cid asks the team where Yang is, but the party members are too distraught to answer with complete sentences. Unfortunately, incomplete Japanese sentences don’t translate well into English, so the phrasing feels a bit unnatural in the Super NES release:

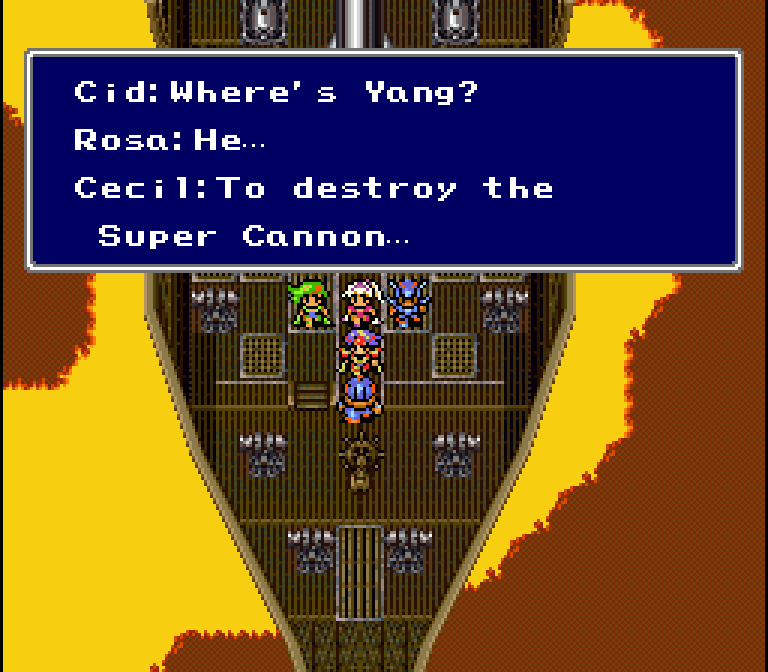

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Cid: ? Where’s Yang? | Cid: Where’s Yang? |

| Rosa: Well, you see… | Rosa: He… |

| Cecil: He stopped the giant cannon and… | Cecil: To destroy the Super Cannon… |

It’s just a minor detail, but it’s an example of what happens when an incomplete sentence is translated literally into English. So if you’re ever playing a translated game and see unusually worded incomplete sentences, this might be the cause.

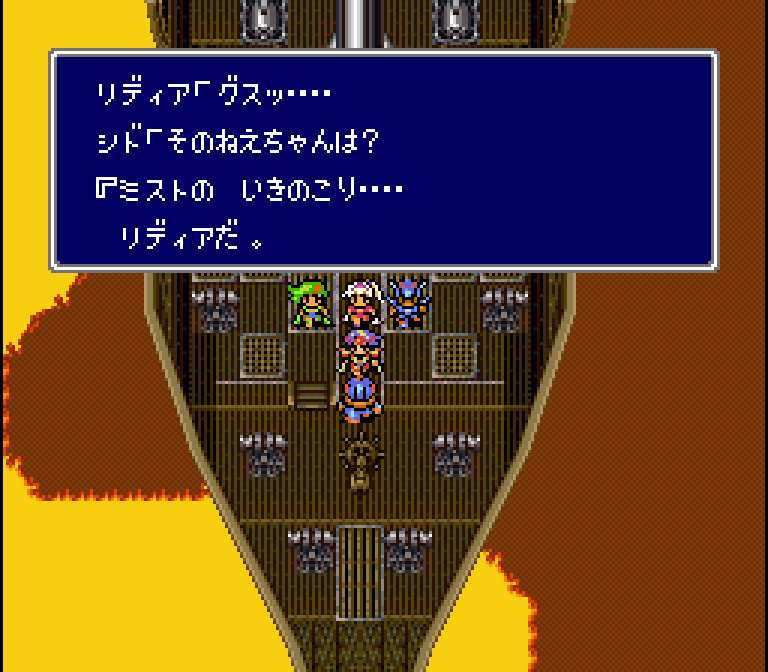

The conversation continues aboard the airship:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Rydia: *sniffle*… | Rydia: Poor Yang… |

| Cid: Who’s this gal? | Cid: Who’s this girl? |

| Cecil: A survivor of Mist… Rydia. | Cecil: Rydia… The Caller of Mist. |

Here, we see two main points of interest:

- Rydia’s sniffle onomatopoeia was replaced with actual dialogue.

- Cecil calls her a “Caller” rather than a “survivor”. By calling her a survivor of Mist and lingering on the phrase with an ellipsis, the game’s writers show that Cecil still feels great remorse for what he did in Mist at the start of the game. That clear remorse is missing in the English script, however.

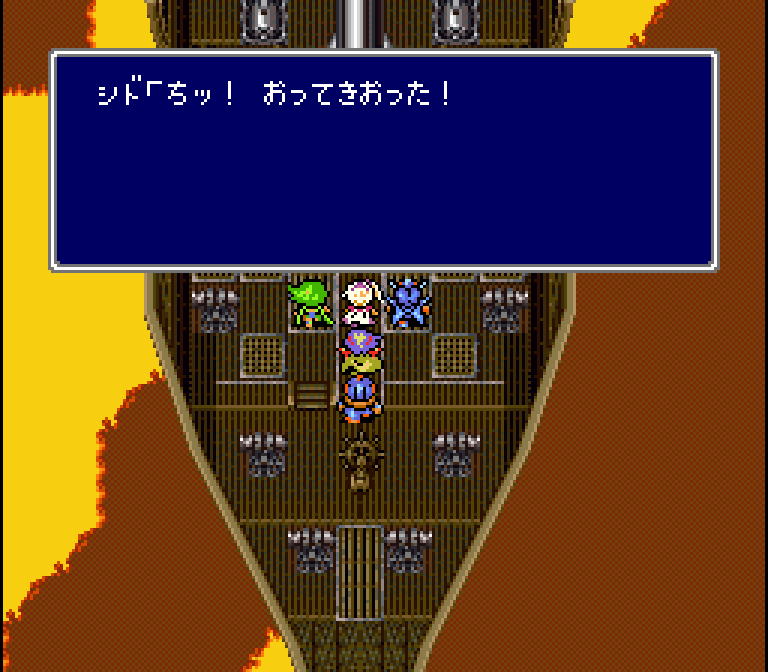

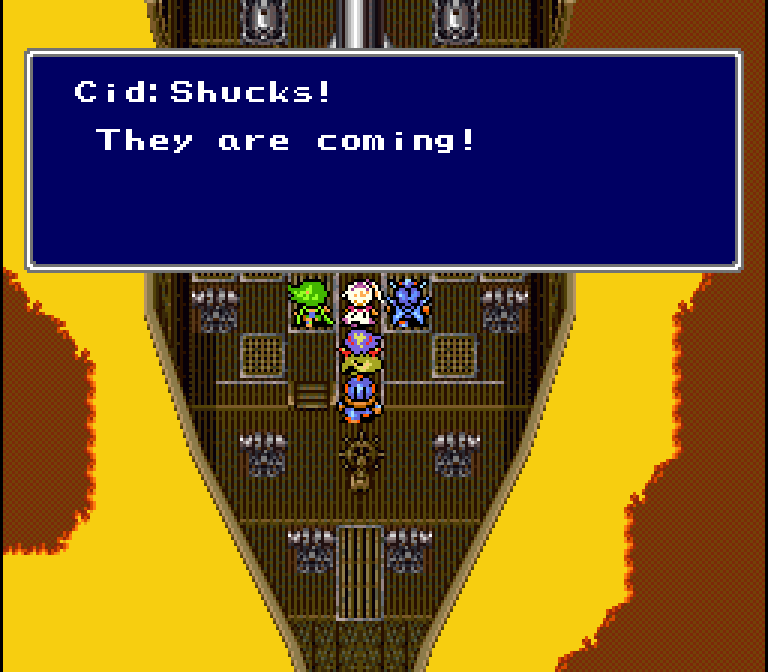

Immediately after this, the Red Wings start to pursue the heroes’ airship:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

In Japanese, Cid responds with a “Tch!” sound that doesn’t really have a clear counterpart in English. Different translators translate this sound in different ways – many just leave it as “Tch”, in fact. Some translators might even replace it with an English swear word that’s appropriate to the situation and character.

In the Super NES English translation of this scene, however, Cid says “shucks”, which is a choice I don’t think I’ve seen before. It also seems uncharacteristic of the majority of the game’s translation, which leads me to wonder if it might’ve been revised by a native English speaker at some point. Or maybe it was even a harsher word at one point and was toned down to “shucks”. Whatever the case, while I never really paid it attention before, the word immediately stands out whenever I see it now.

Cid offers to sacrifice himself to let the heroes escape:

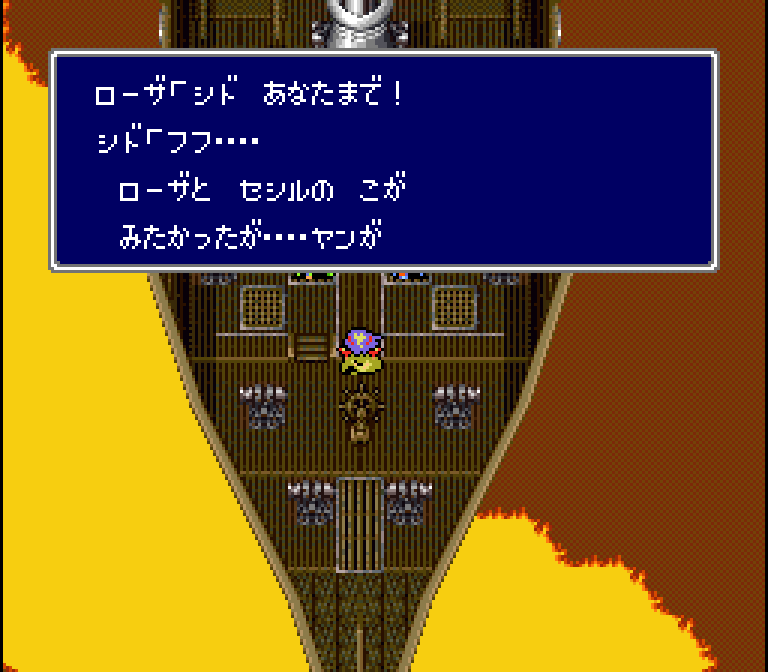

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

Rosa responds to this in Japanese by saying, “Not you too, Cid!” She’s referencing the fact that Yang just died protecting them and can’t bear to have Cid do the same. In English, she simply says, “Oh, Cid…” which dilutes the intended emotion.

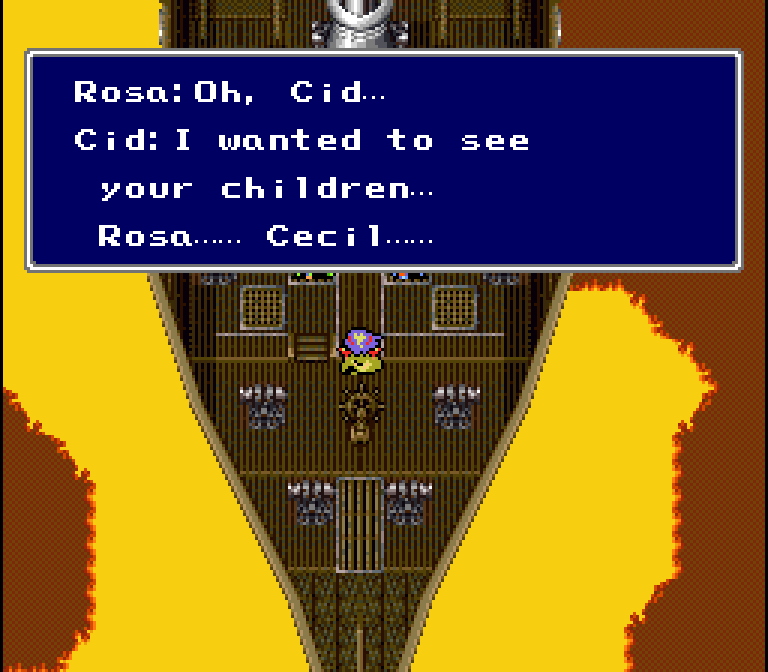

These differences so far have been relatively minor, but then we hit a pretty obvious change: it’s very clear in the Japanese scene that Cid is ready to kill himself to help the heroes escape:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

In the Super NES script, Cid says, “But I guess I’ll stay here a while.” This change not only removes the unstated reference of suicide, it also spoils the fact that Cid actually survives his suicide bomb and meets the heroes later in the story.

This extra English line reminds me so much of how children’s entertainment avoided this sort of thing in the 90s. Here’s a quick example from Dragon Ball Z, which adds the line “Look, I can see their parachutes! They’re okay.” into the background after a bunch of helicopters get blown up:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

After Cid decides to sacrifice himself, Rydia responds in Japanese by saying ojīchan ("old man, grandpa"). To this, he replies, “At least call me ojichan ("middle-aged man, uncle")!”

In the Super NES translation, Rydia shouts, “Come on!” and Cid replies with, “Be good, Rydia!”

Later translations change the lines in other ways – let’s take a quick look.

The PlayStation translation drops the “old man” reference but reintroduces the “uncle” part:

|  |

As expected, the Game Boy Advance translation is basically the same as the PlayStation translation but with a few tweaks:

|  |

And similarly just as expected, the PSP translation is basically the same as the GBA translation, but with a few new changes of its own:

|  |

The DS translation changes things entirely while keeping Cid’s lighthearted response intact:

|  |

After Cid blows himself up with a bomb while plummeting to the ground, the heroes react to what just happened:

|  |

| Final Fantasy IV (Super Famicom) | Final Fantasy II (Super NES) |

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Version |

| Rydia: Why is everyone… | Rydia: Why!? |

| Cain: They’re all in such a damn hurry to die! | Kain: It’s too dangerous! |

Rydia’s reaction in Japanese is in reference to multiple people sacrificing themselves, but her reaction in English arguably seems more in response to Cid’s sacrifice only. The harsh language and the mention of death were left out of the translated scene as well.

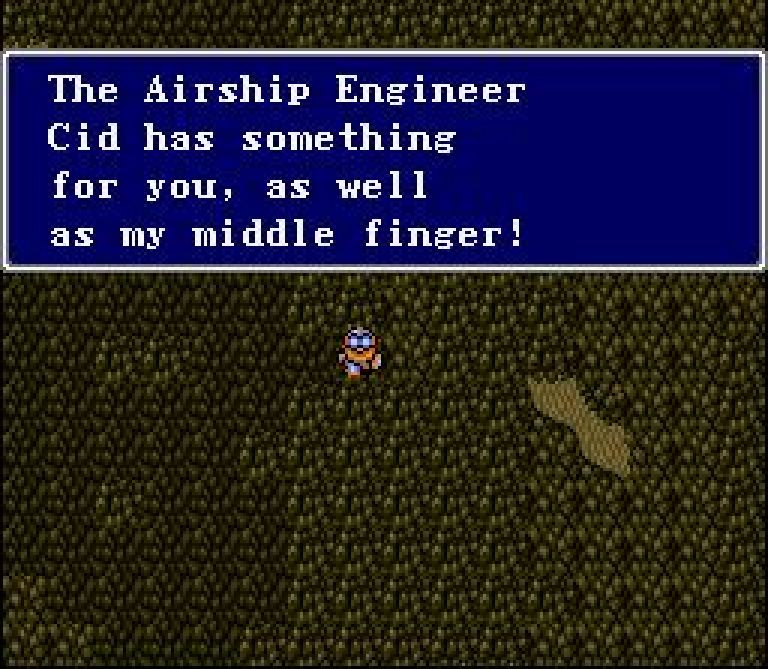

Fan Translation Harsh Language

For fun, here’s how the J2e fan translation handles a variety of lines from this tiny slice of the game’s story:

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/bbenma.png)

What does this error message look like in the other versions?

The messiness of etymology in “Lugaeborg” seems to be coming from the difference between English “CybOrg” vs Japanese pronunciation/understanding of “Sai-Boogu”.

As a native Japanese speaker living in SNES FF4 released in Japan, I don’t think that Lugaeborg is coming from Gáe Bulg at all. Gáe Bulg is pronounced as “Geiborugu” in Japanese and not so popular in video game culture at that time of FF4 releasing.

It is just coming from “Lugae + Cyborg = Lugaeborg” and the sense of language does not fit to English portmanteau but fit to Japanese Katakana language.

As we know that “Cyborg = Cybernetic + organism” so the portmanteau of “Lugaeborg” is incorrect in English.

As a native Japanese speaker living as my childhood at that time, I know Dragon Quest 6 has a monster named Megaborg (means “mega cyborg”). Also DQ has such portmanteau monster names like “Slimeborg” (Slime cyborg) and “Naumannborg” (Naumann Elephant cyborg).

This using “-borg” portmanteau in Japanese language makes sense as the meaning of “something of cyborg version”.

Cyborg is understood as “Saiboogu” in Japanese language sound so it is divided into “SaiBoogu”.

In addition, not relating to the meaning of Cyborg but focusing on pronunciation of “Sai”, this part is just same sound as “Psy” of ESPER (Psychic) being popular at that time of FF4 (around 1990) so Japanese Katakana word culture unconsciously understood as “Sai” of “SaiBoogu” is correct dividing and using as cool SF prefix. Then “Cy” is removed and remained “borg” is used for Lugaeborg meaning Lugae Cyborg.

Simply speaking, we know it is definitely incorrect based on English etymology of “CybOrg” but it is understood as “Sai-Boogu” Japanese Katakana word at that time of FF4 releasing.

I feel like “Lugae” is hemmed in by other words, pronunciation and connotation, “-eie” constructions sound really awkward in native English, I can’t think of any English word that uses a hard sound before ‘eie’ or even come up with how you’d really pronounce that. “Lugie” and “Lugeie” bring to mind boogers or mucus, and “rugae” are a feature of intimate female anatomy, so those are no-go. “Rugie” is possible I suppose but it wouldn’t be my first choice and it doesn’t have the right sort of feel for a doctor (maybe for a country bumpkin type or a tough guy, not a doctor). Plus the latinate “ae” dipthong occurs a lot in medicine and science so there’s a natural mental connection there. It just Lugae “feels like it fits” better than any alternative and avoids an unintentional connotation or meaning.

There’s also

The name “Lugae” is said to be reciting of “Ole Lukøje”, a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ole_Luk%C3%B8je

“Ole Lukøje” pronunciation in Danish language is fitting to Lugae in Katakana word pronunciation.

https://www.pronouncekiwi.com/Ole%20Luk%C3%B8je

Such kind of citation from European classics are very popular methodology at that time of FF4 in Japan.

The Golbez Big-Four Servants (Rubicant/Rubicante, Valvalis/Barbariccia, Kainazzo/Cagnazzo, Milon/Scarmiglione) are the citation from Dante’s Divine Comedy characters. Also Calcabrina is being inside the Dante’s work.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malebranche_(Divine_Comedy)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Characters_of_the_Final_Fantasy_IV_series#Rubicante

Wow, that last scene in the fan translation is basically the perfect encapsulation of everything Clyde’s been saying about that script. The whole thing just feels like some first year university students in Japanese 101 decided they knew enough to tackle the project and bothered one of the kids in Japanese 303 to occasionally pitch in. The crazy swearing and random “edgy” dialogue also reeks of the early “adult” anime influx in the 90’s, when pretty much every show or movie that managed to get a translation was hideously violent and had lots of swearing.