This is part of my ongoing series in which I compare four translations of Final Fantasy VI with the original Japanese script. For project details and my translation notes from Day 1, see here.

Part 7B: Opera Scene

We streamed the Zozo section of the game and the opera scene section all in the same stream, but both parts were so heavy with info that I decided to break it into two parts. Even then, these two parts wound up so info-dense that it took me longer than usual to write everything up.

Video Archive

Notes

Since the opera scene in Final Fantasy VI is so iconic, I was hoping to give a super-detailed look into here. I started to get too ambitious, though, so if you’re interested in learning more, definitely check the video above. But if I’ve missed anything major here, let me know in the comments and I’ll update this article as needed.

Getting Fired

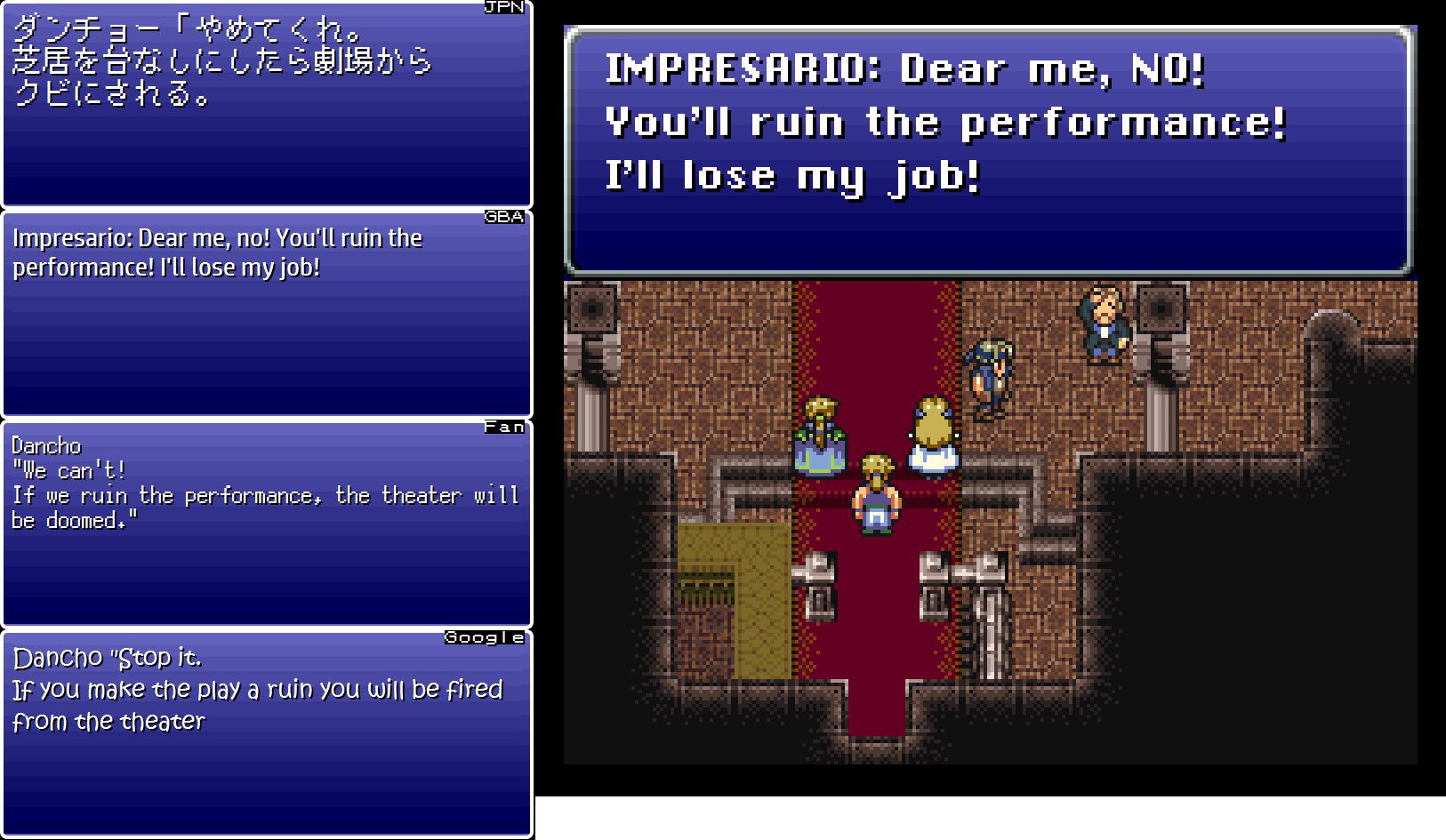

The whole opera section of the game begins with the Impresario worrying that the opera will get ruined. In Japanese, he’s worried that he’ll get fired from the theater if the performance is a failure. But in the fan translation, he’s instead worried about the theater itself – his livelihood no longer has anything to do with his worries.

Opera Floozy

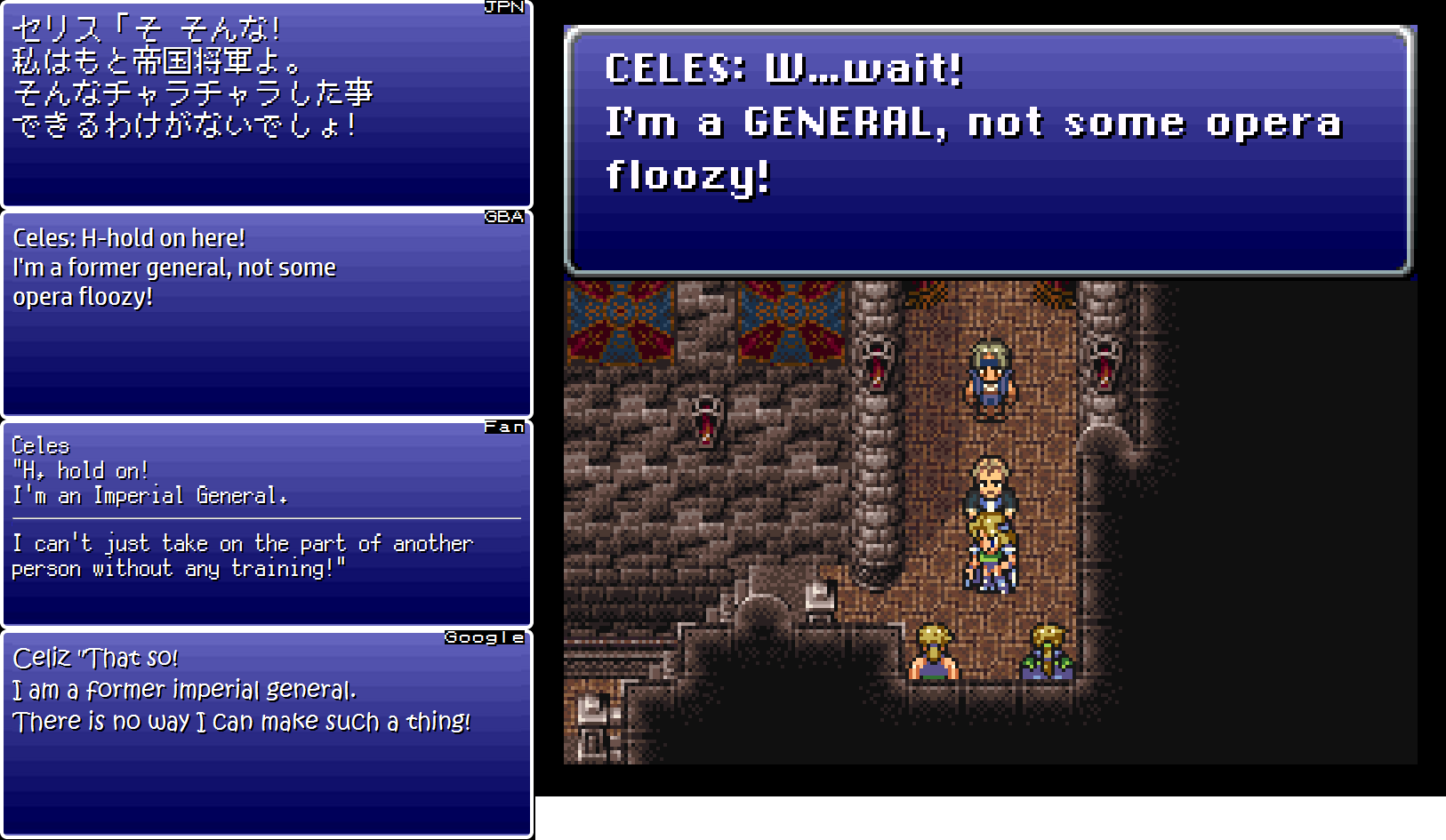

Celes hears about the plan to use her as a decoy actress during the opera. Her response in the Super NES translation is one of the most iconic lines in the game:

I’m a GENERAL, not some opera floozy!

In Japanese, the line is closer to: “I’m a former imperial general, you know. There’s no way I can do anything that superficial/flashy/frivolous!”

The GBA translator recognized the iconic status of the Super NES line and decided to keep it as-is. Except the Super NES line had one little mistake in it: Celes used to be a general in the Empire, but she isn’t anymore. Even the Japanese line mentions this by using the word “former”. So we again see the GBA translator paying tribute to the previous translation while also patching up flaws as needed.

The fan translation gets the line wrong. First, the mention of “former” is missing from the translation, just as it’s missing in the Super NES translation. Next, Celes says that she can’t be in the opera because she “can’t take on the part of another person without any training”. That’s not what she says in Japanese at all. It’s not about being trained or not, it’s about how she sees herself.

Early Details

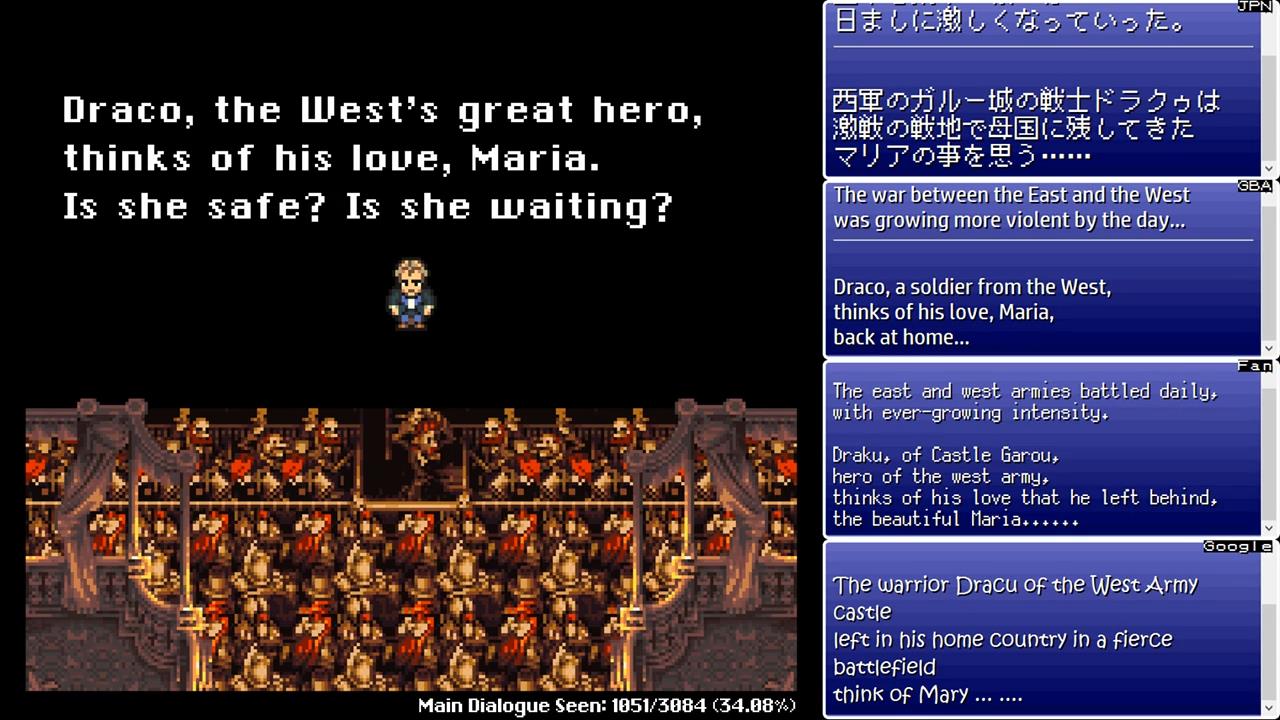

Throughout the opera we’ll see that some details get changed or got left out. For example, in this introductory part, the Japanese script mentions that Draco is from “Castle Garū”. This detail is dropped from the official translations – now Draco is just a soldier from “the West”.

The fan translation is the only one that keeps the castle detail intact. For some strange reason, even Google drops the name of the castle. I guess it didn’t know what to do with the word “Garū”.

Opera Pre-Show

The opera singing begins after the Impresario’s opening narration. But before we start looking into the opera in detail, there’s some important stuff to know.

Way back when I was a university student, one of my translation professors gave us a little homework assignment on the very first day of class. He gave us a short poem by a famous Japanese poet and told us to translate it before the next class.

When the next class rolled around, we were asked to recite each of our poems in front of the class. To our amazement, all our translations were very different – you could barely tell that they were even from the same source text. Apparently the poem was from some old famous poet known for packing multiple meanings into every word he could. Unfortunately, I don’t recall the guy’s name, but I still vividly remember that feeling of surprise. How could the same thing be translated in so many different ways?

The lesson we learned is that different people experience different things from the same poem, same song, or same whatever. As a result, things like poems and songs can end up translated in many different ways. So the natural question is: which way is correct? Is there even a “correct”? It’s tough.

On top of this fundamental translation problem comes an entirely different problem too: if you want to translate a poem or song and want to keep it as a poem or song in the new language, then you’ll almost certainly have to make some big changes. Otherwise, lyrics won’t fit the music, syllables won’t match up the way they’re supposed to, etc.

I bring all this up because song translation – including the opera in Final Fantasy VI – involves so many more issues than ordinary dialogue translation. And, unless you’re analyzing lyrics on a literal level, most song translations are probably more of an adaptation than a straight translation.

It’s a lot like when a book gets adapted into a movie: there are certain plot elements and beats that the movie tries to cover, but because books and movies are so fundamentally different, lots of changes have to get made. Sometimes new things get added in while other things get cut out. So if you try to compare them side by side afterward to see if anything changed, of course you’ll find changes – that’s how adaptations work.

Anyway, I don’t expect the various translations of this Final Fantasy VI opera scene to vary wildly or anything, but I feel it’s important to explain how song translation goes by different rules. Especially since the opera lyrics are an adaptation in almost every translation we’re looking at here.

Opera, First Section

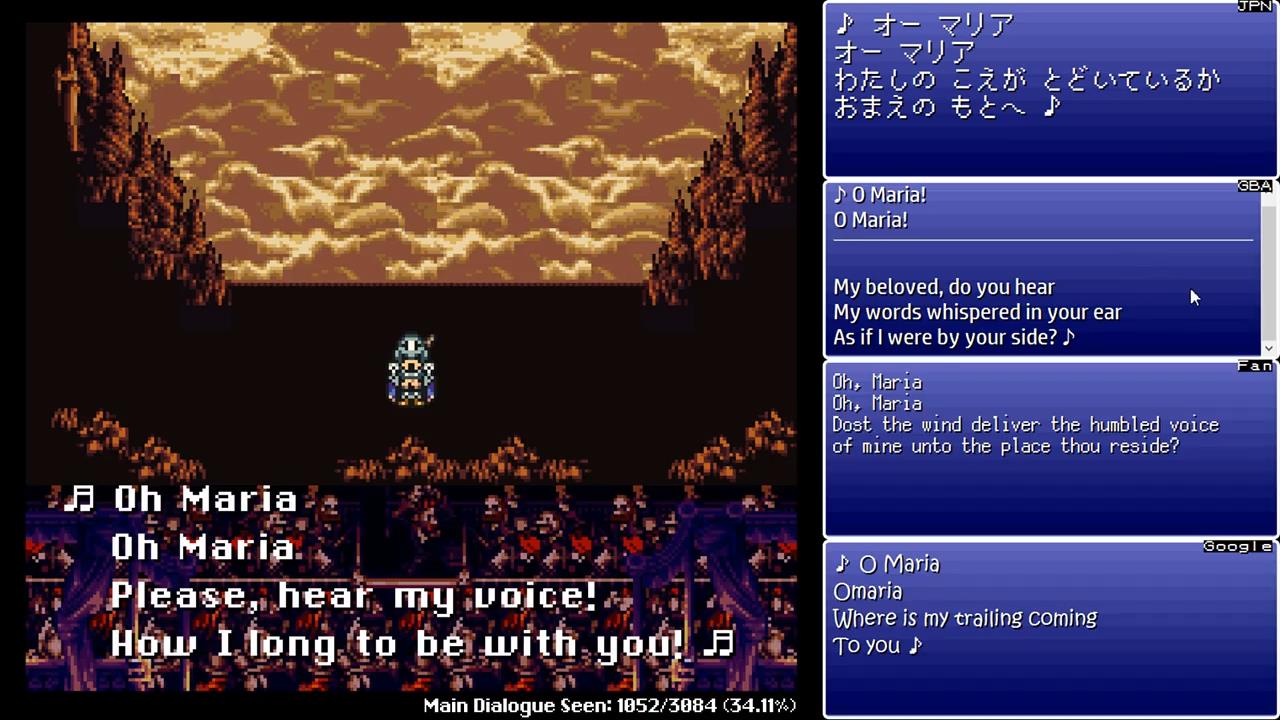

First, let’s look at the Japanese lyrics. I’ve included the audio for this part so that you can see how the Japanese lyrics fit with the music. Note that I’ve put a / mark between some of the syllables to help, in case you’re not familiar with how Japanese syllables combine.

Now that I think about it, you could also use this to learn the lyrics and sing them at Japanese karaoke sometime!

| Japanese Text | Pronunciation | Basic Translation |

| オー マリア | ō ma/ri/a | Oh, Maria |

| オー マリア | ō ma/ri/a | Oh, Maria |

| わたしの こえが とどいているか | wa/ta/shi no ko/e ga to/do/i/te i/ru ka | Does my voice reach |

| おまえの もとへ | o/ma/e no mo/to e | to where you are? |

Now let’s look at what the two official translations and the fan translation do. I’m leaving the machine translation out here just to streamline things, but I hope someone will sing the machine translation lyrics someday somehow!

| Super NES Version | GBA Version | Fan Version |

| Oh Maria | O Maria! | Oh, Maria |

| Oh Maria | O Maria! | Oh, Maria |

| Please, hear my voice! | My beloved, do you hear My words whispered in your ear | Dost the wind deliver the humbled voice |

| How I long to be with you! | As if I were by your side? | of mine unto the place thou reside? |

Right off the bat we can see that the GBA translation has lyrics that match the music much more clearly than the Super NES translation. The GBA translation also keeps the meaning a little closer to the original text while also adding some artistic flair.

We see that the fan translator opted to give the lyrics an olden English vibe. I had trouble hearing how some of the lyrics match the music, but I’m absolutely tone deaf and have no musical talent, so that’s probably just my own fault.

Incidentally, the GBA translation of this entire opera is apparently used in actual, real-life performances of the game’s opera. Man, as a translator, I bet hearing your work being sung by professionals in a fancy opera house is an amazing feeling!

Anyway, this short little piece of singing has already given us a good idea of what to expect in the upcoming opera scenes.

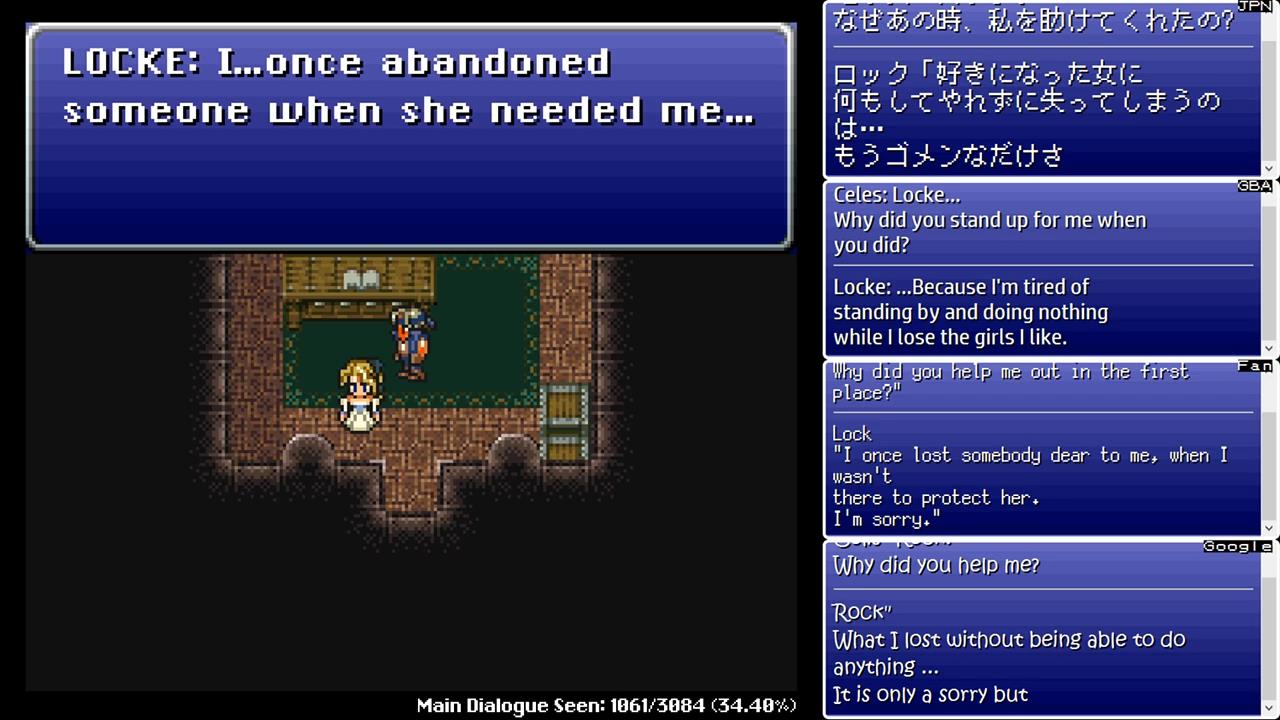

Don’t Be Sorry

Locke goes backstage during the performance to chat with Celes. At one point, Celes asks why Locke helped her escape South Figaro earlier in the game.

In Japanese, Locke says something like:

I’m… tired of losing girls I like after being unable to do anything for them.

The Super NES translation isn’t quite the same, but the connection to Rachel is made clear at least. The GBA translation clarifies things by fully translating the line.

The fan translation makes a simple mistake: the Japanese word gomen is often an informal way of saying “sorry”, but in other contexts it means you’re sick and tired of something and hate it. My hunch is that the fan translator hadn’t yet learned about the latter usage, even though it’s pretty common to hear. Even so, the line is largely a rephrasing of the flawed Super NES line anyway.

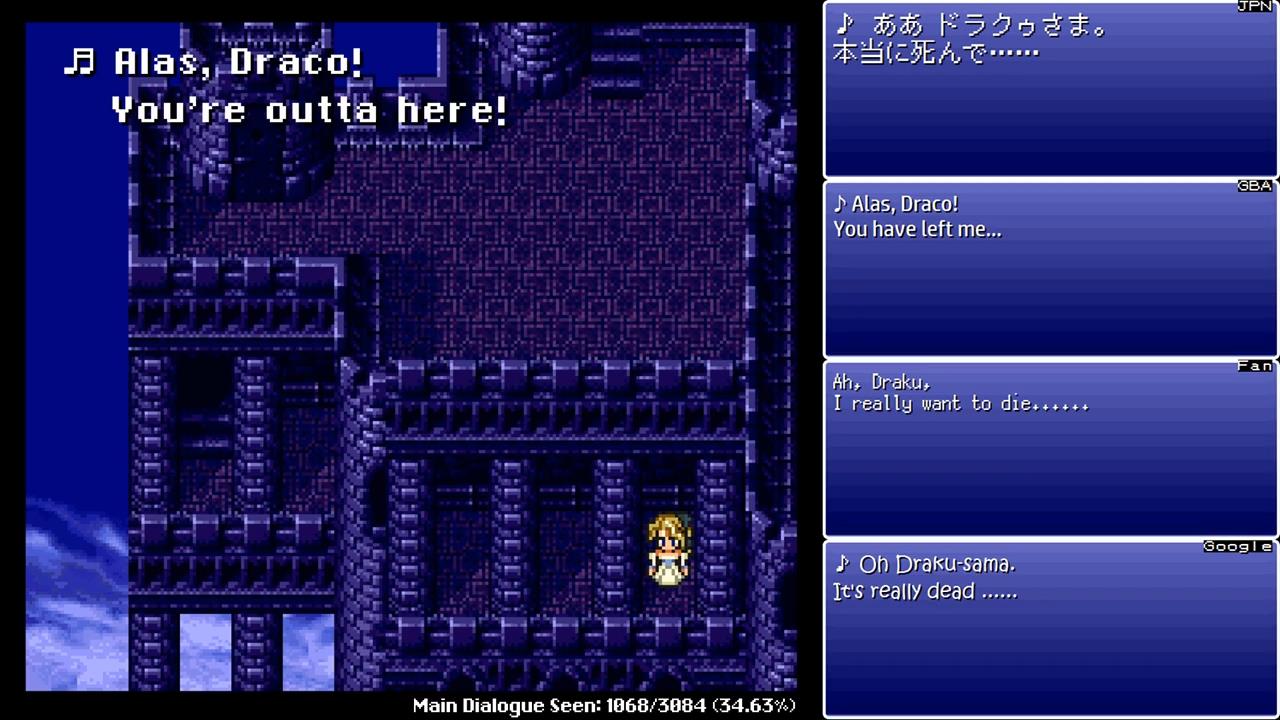

Opera Failure

Eventually, you take control of Celes as she performs her part of the opera. You’re supposed to memorize her lines and choose the right lines when prompted. If you get a line wrong, you get kicked out of the theater and have to try again.

During the stream, I tested this failure thing out with the first line prompt. In Japanese, when this first line is messed up, Celes sings a sentence fragment that can be translated as “Oh, Draco, please really die.” or maybe even “Oh, Draco, are you really dead?”. After this, she apologizes for messing up.

In the Super NES line, Celes instead says, “Alas Draco, you’re outta here!” or something like that. It’s such a strange line that at first I thought someone was yelling at Celes and telling her that she’s getting kicked out of the theater. But on closer thought I think this “outta here” line was just a way to avoid the reference to dying that’s in the original script.

The GBA translation also goes a different route than the dying reference. Only the fan and machine translations keep the death talk intact.

Opera, Second Section

Celes gets her time to shine during the opera. First, here are her Japanese lyrics, their pronunciation, and what they mean.

| Japanese Text | Pronunciation | Basic Translation |

| いとしの あなたは | i/to/shi no a/na/ta wa | My beloved, |

| とおいところへ? | to/o/i to/ko/ro e | must you go so far away |

| いろあせぬ とわのあい | i/ro a/se/nu to/wa no a/i | so soon after we pledged |

| ちかったばかりに | chi/ka/tta ba/ka/ri ni | our eternal, unfading love? |

| (pause) | ||

| かなしい ときにも | ka/na/shi/i to/ki ni mo | During sad times |

| つらいときにも | tsu/ra/i to/ki ni mo | and during painful times |

| そらにふる あのほしを | so/ra ni fu/ru a/no ho/shi o | I will think of that star falling in the sky |

| あなたとおもい | a/na/ta to o/mo/i | as you |

| (pause) | ||

| のぞまぬ ちぎりを | no/zo/ma/nu chi/gi/ri o | Must I exchange vows |

| かわすのですか? | ka/wa/su no de/su ka | that I do not want? |

| どうすれば? ねえあなた? | do/o su/re/ba ne/e a/na/ta | What should I do? Tell me, my darling |

| ことばをまつ | ko/to/ba o ma/tsu | I wait for your words |

| (dance sequence) | ||

| ありがとう わたしの | a/ri/ga/to/o wa/ta/shi no | Thank you, |

| あいするひとよ | a/i su/ru hi/to yo | my love, |

| いちどでも このおもい | i/chi/do de mo ko/no o/mo/i | for silently and gently |

| ゆれたわたしに | yu/re/ta wa/ta/shi ni | answering me |

| しずかに やさしく | shi/zu/ka ni ya/sa/shi/ku | even after my feelings |

| こたえてくれて | ko/ta/e/te ku/re/te | briefly wavered if but once |

| いつまでも いつまでも | i/tsu ma/de mo i/tsu ma/de mo | I will forever, forever |

| あなたをまつ | a/na/ta o ma/tsu | wait for you |

Next, here are the two official translations and the fan translation, side by side:

| Super NES Version | GBA Version | Fan Version |

| Oh my hero, so far away now. | O my hero, my beloved, | Oh my dearest, my beloved, |

| Will I ever see your smile? | Shall we still be made to part, | art thou trav’ling far away? |

| Love goes away, like night into day. | Though promises of perennial love | Lest I remind thee that we hath pledged |

| It’s just a fading dream… | Yet sing here in my heart? | our eternal love anew… |

| (pause) | ||

| I’m the darkness, | I’m the darkness, | Amongst this time of depression, |

| you’re the stars. | You’re the starlight | melancholy and sorrow, |

| Our love is brighter than the sun. | Shining brightly from afar. | I can only reminisce of thee whilst gazing upon the night stars… |

| For eternity, | Through hours of despair, | |

| for me there can be, | I offer this prayer | |

| only you, my chosen one… | To you, my evening star. | |

| (pause) | ||

| Must I forget you? Our solemn promise? | Must my final vows exchanged | Shall I proceed and pledge vows |

| Will autumn take the place of spring? | Be with him and not with you? | With the one whom I not love? |

| What shall I do? | Were you only here | What else can be done? |

| I’m lost without you. | To quiet my fear… | Thus I now wait… |

| Speak to me once more! | O speak! Guide me anew. | And wish for thy reply… |

| (dance sequence) | ||

| We must part now. | I am thankful, my beloved, | And I thank thee, my beloved, |

| My life goes on. | For your tenderness and grace. | my dearest and my love, |

| But my heart won’t give you up. | I see in your eyes, | For even amongst my swayed feelings |

| Ere I walk away, let me hear you say. | So gentle and wise, | |

| I meant as much to you… | All doubts and fears erased! | And my changed heart… |

| So gently, you touched my heart. | Though the hours take no notice | Thou so gently, and so kindly, |

| I will be forever yours. | Of what fate might have in store, | Thou truly answered me. |

| Come what may, | Our love, come what may, | And thus I shall wait, |

| I won’t age a day, | Will never age a day. | for thee forever, |

| I’ll wait for you, always… | I’ll wait forevermore! | forever more. |

I have a deep fondness for the original Super NES translation of this scene – it was the first version I encountered and the only one I’ve known for the past 25 years or so. Despite that, though, the GBA version is by far my favorite version now. I’m impressed how it was able to keep the core ideas and retain the key imagery, all while keeping the song an actual song.

I’ve translated more songs than I can remember during my own career, but usually never for the purpose of actual singing. In the few instances that my song translations needed to be sung by someone, actual songwriters and musicians were usually brought in to adapt the lyrics to match the original music. From what I can tell, the GBA translator handled the translation, localization, and all of that extra work by himself.

That’s not to say I don’t like the Super NES version anymore, but I have to admit that for many of the SNES lyrics I always had trouble figuring out how some lines were supposed to match the music.

Opera, Third Section

The final part of the opera features multiple actors and not just one. It’s not as meaningful or poetic as Celes’ song, but it’s worth checking out anyway.

First, let’s check out the Japanese lyrics, their pronunciation, and basic meaning:

| Japanese Text | Pronunciation | Basic Translation |

| マリア | ma/ri/a | Maria |

| ドラクゥ このひを しんじてた。 | do/ra/ku ko/no hi o shi/n/ji/te/ta | Draco I always believed this day would come |

| マリアは このわたしの きさきになる べきひとだ | maria wa / kono watashi no / kisaki ni naru beki hito da | Maria is meant to be my queen |

| いのち つきはてよう とも はなし はしない。 | i/no/chi tsu/ki ha/te/yo/o to/mo ha/na/shi wa shi/na/i | Even if my life should expire, I will not let her go |

| けっとうだ! | kettо̄ da | It’s a duel! |

Next, here’s how the two official translations and the fan translation look side by side:

| Super NES Version | GBA Version | Fan Version |

| Maria | Maria! | Maria! |

| Draco, I’ve waited so long. I knew you’d come. | Oh, Draco! I knew you would Come for me, my love! | Draku! I always knew that this day would come. |

| Maria will finally have to become my queen! | Insolent rogue! Knave of the Western horde! You would address my queen to be, Maria? | Maria shall finally be mine! She shall become my wife and queen. |

| For the rest of my life I’ll keep you near… | Never shall you have Maria’s hand! I would die before that day comes! ♪ | Even if it costs me my life, I refuse to let her go. |

| It’s a duel! | Then it’s a duel! | Then we shalt duel! |

Looking back on all of these opera lyrics, it’s clear that the Super NES lines are shorter than all the others. This follows the same pattern we’ve seen for all dialogue in the Super NES version, so it makes me wonder if some of the SNES lyrics were shaved down from the translator’s first draft translation and then stretched to fit. If so, then it’s impressive that the original translation remained so iconic despite those compromises.

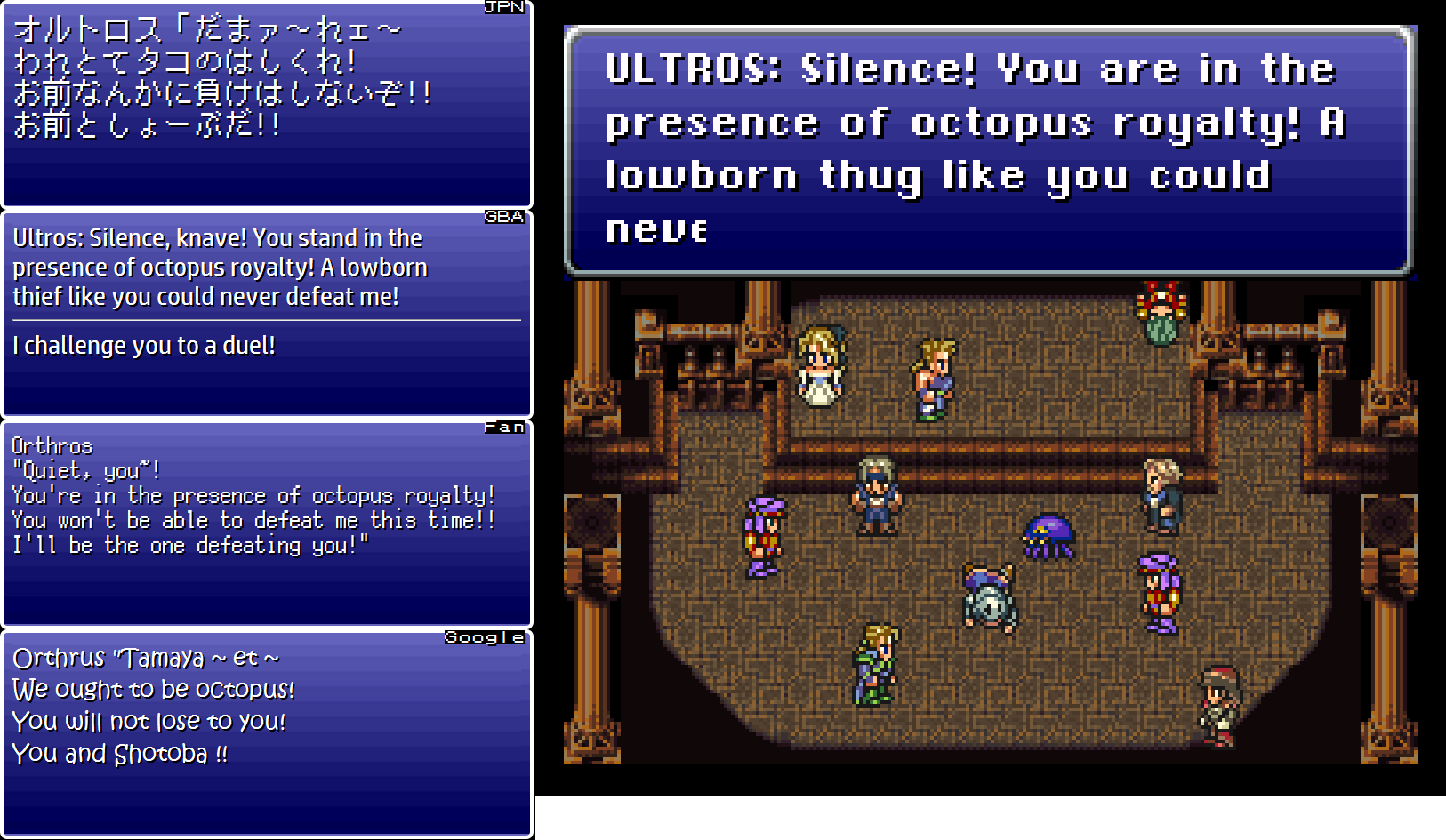

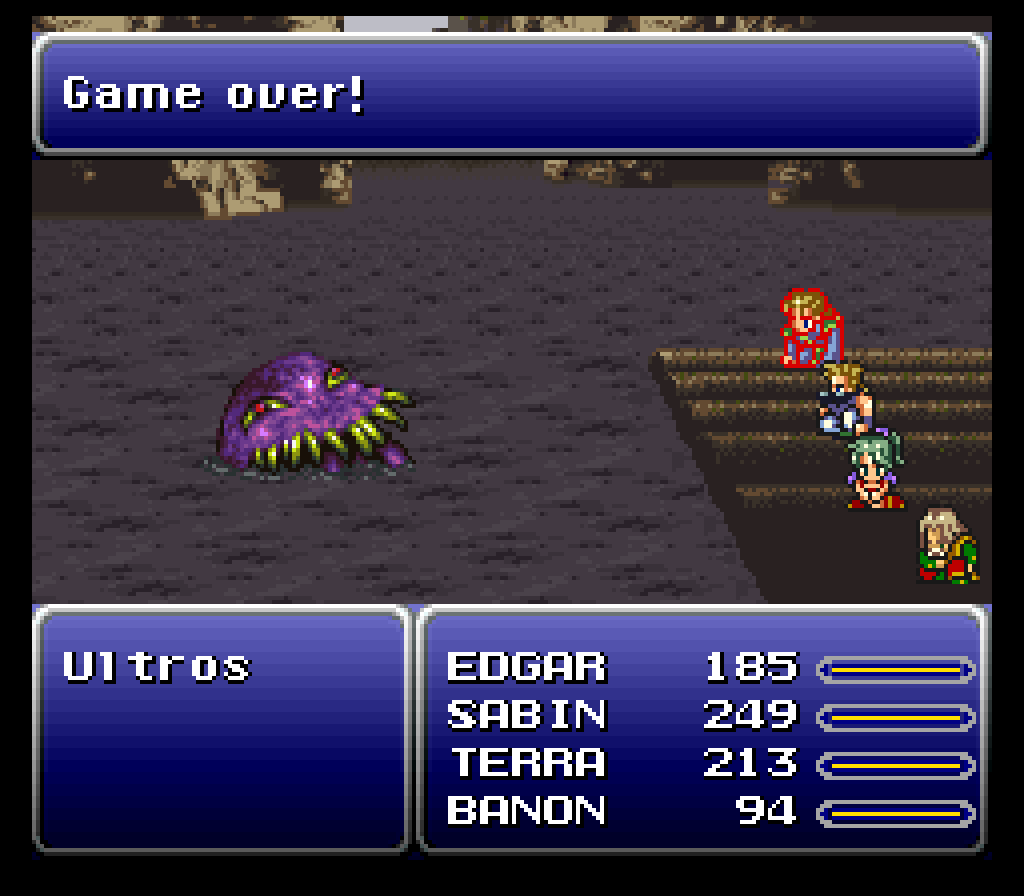

Octopus Royalty

Locke and Ultros accidentally fall onto the stage during the middle of the opera. They do some bad acting to pretend that it’s all part of the play, but the crowd boos in response to both of them.

One of Ultros’ lines in the Super NES translation has become a fan favorite over the years:

Silence! You are in the presence of octopus royalty!

This “octopus royalty” thing is loved enough that it was kept in the GBA translation as well. But in Japanese, Ultros says nothing of the sort. His actual line could be translated in many ways, but it all basically boils down to something like:

Silence! Though I may not be a great one, I am an octopus, you know!

In other words, his cheesy line in Japanese means he’s just some minor, petty octopus, which is the exact opposite of being “octopus royalty”.

More than anything, I feel Ultros’ line was changed in translation for the Super NES release to sound more over-the-top and befitting of the situation Locke and Ultros fell into.

The fan translation uses the “octopus royalty” phrase too, so it’s clearly using the Super NES translation as a base here to some degree.

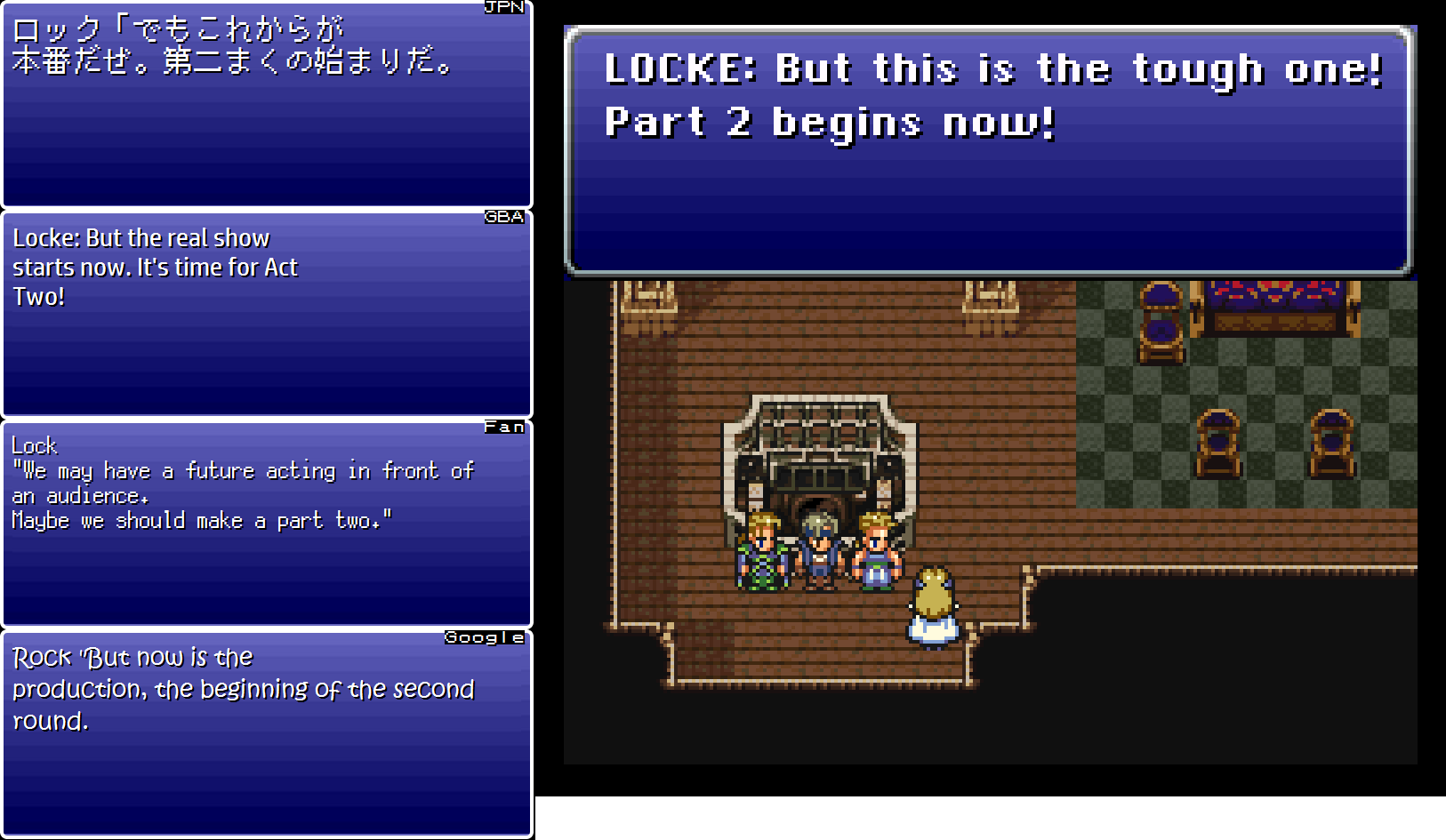

Just Getting Started

After Celes and the others manage to sneak aboard Setzer’s airship, Locke says in Japanese:

But now the real show begins. It’s time for Act 2.

This “Act 2” isn’t referring to the actual opera anymore. Instead, he’s saying that their “Act 2” is to convince Setzer to let them use his airship.

The fan translator had difficulty understanding this wit, so this entire line ends up incorrectly translated.

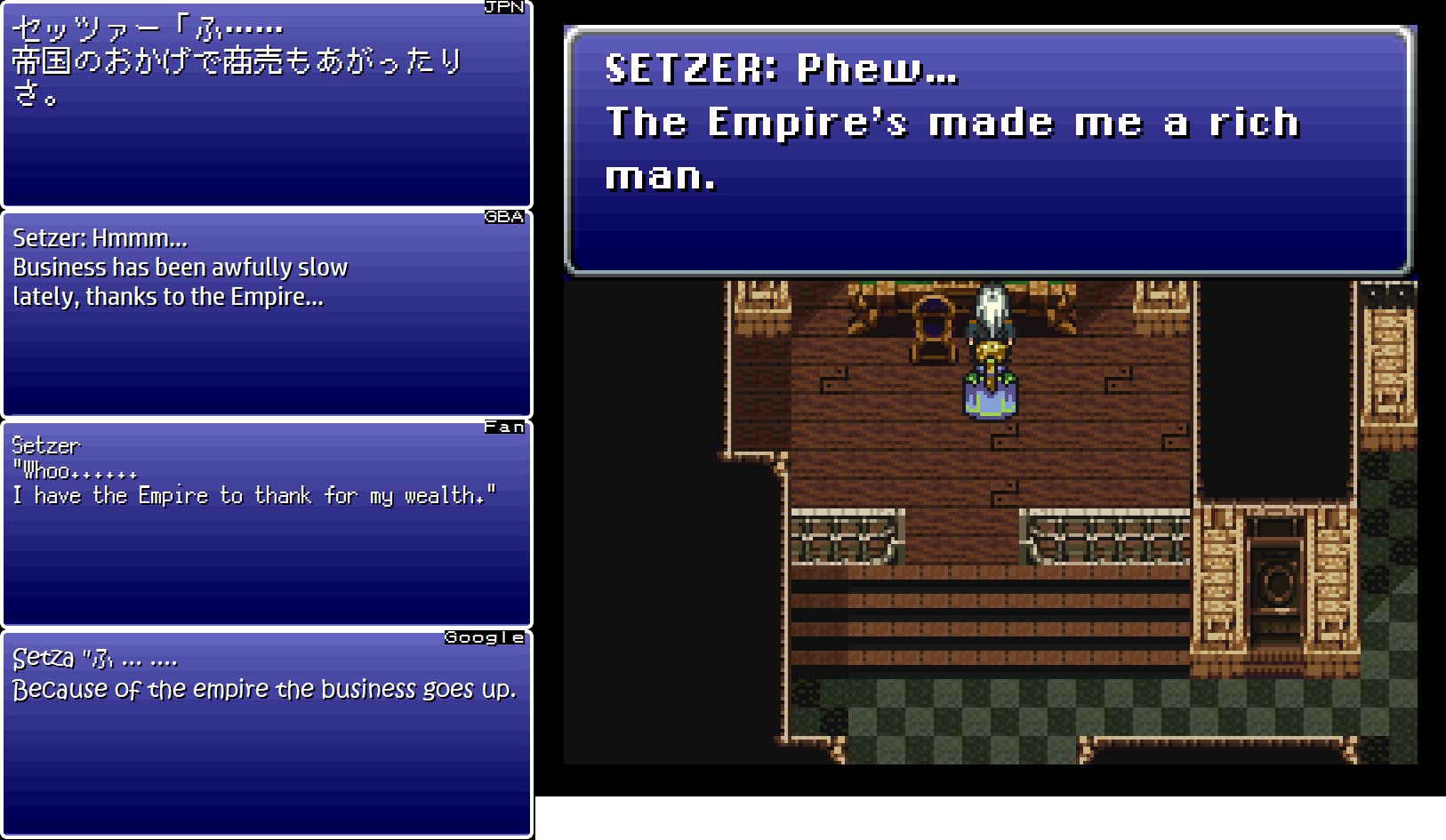

Setzer’s Famous Mistranslation

The heroes try to persuade Setzer to help them work against the Empire. At one point, Setzer says in Japanese:

Thanks to the Empire, business has dried up.

The actual word used is あがったり (agattari), and is connected to the word あがる (agaru), which generally means “to go up”. So if you weren’t familiar with agattari, you might assume this line is saying “business has gone up”. It actually means just the opposite, however! Rather than think of agattari as “go up”, it’s easier to view it as something like “dry up” or “go up in smoke”.

Anyway, the Super NES translator fell for this translation pitfall and wound up changing Setzer’s motivation entirely. The GBA translation fixes the glaring problem, while the fan translation gets the line incorrect for the same reasons as the Super NES translation.

On a side note, this fix in the GBA translation was actually perceived as an error or as censoring back when it was released:

Actually, a few years back, the GBA translator did an interview for RPGamer and discussed some of his Final Fantasy VI work. The topic of this exact line came up:

[…]that was a mistranslation in the original English script, plain and simple. The expression used in Setzer’s Japanese line is an idiomatic one, shoubaiga agattari, meaning “business has dried up.” Setzer is beginning to reveal that he has no personal love of the Empire, acknowledging that it has been hurting him financially. Celes jumps on this first sign of receptiveness to their appeal, saying literally “It’s not just you,” and encouraging him to think about all of the other people who are likewise suffering at the hands of the Empire.

This translation revelation was big enough to get surprising news coverage:

It’s crazy to think that revealing one mistranslation would cause such a stir!

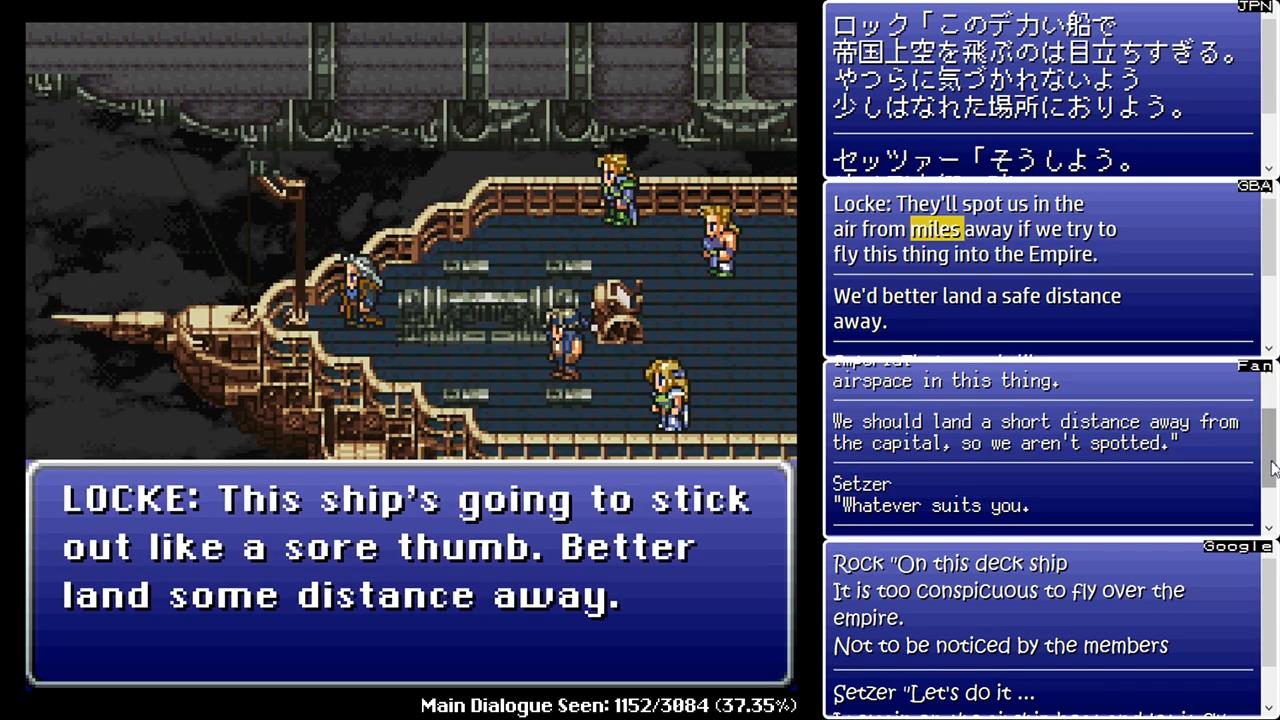

Miles Ahead

In Japanese, Locke says that the airship is so big that it’d really stand out if they flew it over the imperial capital. The GBA translation rephrases this slightly:

They’ll spot us in the air from miles away if we try to fly this thing into the Empire.

This added mention of “miles” in the GBA translation made me pause and wonder if the phrase “miles away” is common outside of America. And I wonder how this line is handled in the other GBA translations into German, French, Italian, and Spanish.

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/bbenma.png)

I believe the answer to how we knew of Blackjack’s name was the soundtrack, where the listing for Setzer’s/Airship’s theme is “The Airship Blackjack”. It still seems obscure; I imagine the real answer is the rise of the internet and Final Fantasy fan sites, which coincided with the release and subsequent popularity of this game. Both the manual and Nintendo Power refer to it as the proper noun “Airship”.

Yeah, I actually went to check a site that had a bunch of SNES manual scans to see if maybe the manual had the name in it. It just says “Airship.” Interesting bit about the soundtrack. That could be where it came from, although were there really commonplace fansites at that time? I feel like those sorts of sites didn’t show up until a few years later.

Final Fantasy VI had a long shelf life (which continues to this day), so it’s hard to remember what I learned in-the-moment and what I gleaned off fan sites approximately two years later. I was also heavily into the soundtrack scene at the time, where full albums from Japan would be downloadable from Simplenet sites. “Blackjack” was definitely prominently featured on these tracks. I remember reading advertisements for the US soundtrack but don’t recall whether I saw a track listing. I didn’t buy the album because it was too expensive at the time ($20-$25?); the game itself was already something like $85. I ended up dubbing to cassette from the SNES.

When I first played FF6 about 20 years ago, (siiiiigh) I borrowed it from a friend who had a strategy guide, I think that’s where I learned the ship is called the Blackjack.

I’m 99% sure it was called The Blackjack in the player’s guide written by Peter Olafson. I wish I still had a copy so I could check, as that guide was legitimately great and almost as entertaining to read as it was to play the game. For my money no guide ever came as close to being that entertaining.

That だまァ~れェ~ is meant to be one of those super-drawn out theatrical deliveries from kabuki, right?

Come to think of it, it’s odd how the drawn-out vowels are in katakana. Is that normal in Japanese written dialogue?

I wouldn’t say it’s normal, but still used regularly in certain situations. It could be used to express something like the speaker has an accent or something.

Also… that “octopus royalty” line is a perfect example of the issues I think Slattery’s translation has.

Woolsey’s translation of the line isn’t accurate, there’s no arguing that, and Woolsey made so many random mistranslations I highly doubt this was some kind of deliberate rewrite. Yet Slattery, who had just finished tossing out Woolsey’s “iconic” opera translation and replacing it with his own, decides this mistranslation is such a sacred cow it needs to stay, accuracy be damned. And this is somehow praiseworthy because… he knew it was inaccurate and didn’t care? While Sky Render copying Woolsey’s mistranslations is a negative if Slattery corrected them in his retranslation?

Yes, I know the difference is that Slattery knows he’s deliberately keeping errors while Sky Render clearly just made assumptions that the Woolsey line WAS correct, but it still has this “it’s okay if it’s inaccurate as long as it’s a Woolsey quote” taste to it that I’m not particularly fond of.

Adamant, we get it. You don’t like that Slattery kept some classic Woolseyisms. Just bare in mind that the ones he kept have no bearing on the story at all. “Son of a submariner” “It’s a little large, but he didn’t charge” has no effect on anything in regards to the actual story of FFVI, and when Woolsey got stuff wrong about the story or characters motivations (the Setzer line saying the Empire is good for business for example is a huge error that completely changes his motivation), Slattery for the most part fixed it. Ultros joking he’s royalty or just an octopus in a scene where he’s obviously ham acting to try to be part of the opera has no bearing on anything before or after it.

Keeping a little of the fun and paying homage to the Woolseyism is fine and I’m sure a lot of fans appreciate it as long as it doesn’t change important story points or conflict with any plot or characters, making it the best of both worlds.

There’s a lot of lines in the game that have no bearing on the overall story, a good deal of which Woolsey got wrong and Slattery fixed. Why is this particular line so important to “preserve”? If Woolsey had given it an accurate translation and Slattery had changed it to what’s currently present in his translation, people wouldn’t be defending it, they’d be wondering why he wrote what he did and most likely assuming he had misread the line or something.

A translation really should stand on its own, and Slattery’s translation does for the most part do that, which is what makes these occasional Woolsey quotes stand out so much. If someone was comparing the Slattery translation with the original Japanese with no knowledge of the Woolsey translation at all, many of these Woolsey quotes would stick out like extremely sore thumbs, and that’s really not how it should be.

It’s the same with those random potential-references to long-forgotten memes – unless you’re familiar with something unrelated to this translation, you just end up scratching your head and wondering why he suddenly decided to write something weird instead of just translating.

I think that some people forget we are reading Legends of Localization, not Legends of Translation.

Slattery kept in the flavor text that held up. There wasn’t some grander motivation.

I think the issue (perhaps it could even be called a double standard) arises because the fan translation’s main goal was to fix everything that the original SNES translation screwed up/censored/etc. It makes sense (to me, at least) that the GBA version would keep some Woolseyisms here and there, since it’s like adding the phrase “It’s a secret to everybody” to the latest Zelda game. It’s a nod to the past.

Holy shit the GBA lyrics are so good. The fan translation gets a B+ for actually sorta trying to fit the lyrics with the music.

I was so impressed with the GBA translation of the opera scene when I played this game. I already knew (from HCBailly’s Let’s Play) that the lyrics didn’t match the music in the SNES version, so when I played the GBA version, I was totally amazed at how well it all fit. It made one of the most iconic scenes in gaming even better.

“This “Act 2” isn’t referring to the actual opera anymore. Instead, he’s saying that their “Act 2” is to convince Setzer to let them use his airship.”

To be honest with you, when I first saw this playing the game as a kid, I thought Locke was breaking the fourth wall by stating Act 2 of the game itself was starting, like to let the player know “The second half of the World of Balance begins here right now!”

Me, too! I always assumed it was a 4th Wall break for comedy’s sake.

I checked the “miles” thing in the Spanish translation and it uses an idiom with the word “leagues” instead.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/League_(unit)

Pretty neat!

Just wondering, what dialect of Spanish was it?

European Spanish. Most games translated at the time didn’t have a Latino Spanish translation.

Okay. I thought so.

When did giving video games two different Spanish translations become common? I’m guessing it was in the 7th generation, but the only game that comes to mind from that era with different European and American Spanish (and English and French) translations is Spirit Tracks. I’m sure there are more, though.

That sounds like a weird thing to do. It’d be like if most video games had an American translation and a British translation. Peninsular Spanish and American Spanish(es) aren’t THAT different.

You joke, but Nintendo’s been doing exactly that for a while now.

Are you talking about English, or Spanish?

English. One of the catalysts for them doing separate British and American English was an incident with one of the Mario Party games. The word “spastic” was used in it, which isn’t really bad in America, but is very offensive in Europe. Having separate English localizations helps avoid problems like that.

Are you from a Spanish speaking country? Because let me tell you, they definitely ARE quite different (in fact some dialects of Spanish can be very difficult to understand to those who speak other variants). Literally every movie and show gets two dubs (some get more, to appeal to different Latin American countries) and people WILL fight on the Internet over which dub is better. It just so happens that this practice of multi-dubbing, for some reason, has only very recently started to become common videogames.

They can be very different, though. You won’t find a lot of Latin American people who are completely unable to understand Spaniard Spanish, but the differences in “linguistic mannerisms” stand out enough as to be perceived as a foreign thing. The differences become stronger when it comes to spoken language, since there’s a clear gulf in how Spanish people pronounce things and how Latin American people do.

…Which is also true for regional differences within Latin America itself. They’re a little subtler, especially when you go to countries that are fairly close together like most Central American countries and the northern region of South America, but they’re there. I grew up in a Spanish-speaking country, Argentina, that has a markedly different dialect than any other Spanish country (with the exception of Uruguay). Every single cartoon I’ve watched on TV was dubbed in what’s commonly referred to as “neutral” Spanish, which is either Colombian or Mexican Spanish (depending on the dubbing company) with all the local regionalisms (mostly) taken out. It was almost impossible to look at them as anything but a foreign thing, even if you eventually got used to it.

Also, with regards to the miles thing: I’ve seen in translated in a myriad ways.

When the number is very specific, I usually see it straight up using the Spanish word for “miles” (millas) or doing a very rough conversion into kilometers.

When there’s no need for specificity in the number, you can probably get away with just using “kilometers”. In some movie translations it’s a little odd when they don’t use the chance to get away from the specificity of the original script when it’s clearly not necessary, but I digress.

Though in this case, I would probably choose from a number of other idiomatic expressions that refer to something being very far away. The official translation (using “leguas”) sounds a little Tolkien-ish to my ear, but I’m not from Spain.

I checked the airship line in German (the first translation was for the GBA version) and it simply says

“This giant ship won’t slip by the Imperials. We should land some distance away”

I actually never really looked at the German translation but as far as I can tell from a quick glance of gameplay and in comparison with your notes it might be a translation directly from Japanese but curiously enough adapting some changes of the English version.

The “octopus royalty” line for example was reworked as “You are standing in the presence of an octopus of royal ink” which wouldn’t really make sense to retain for a translation from Japanese.

However at the same time the entire aria is written closer to the direct translation you gave above. Also some terms like item names and spells are kept line with policies that had been already established by then.

The script also seems to “punch” up a few lines a bit, but not in an awkward way.

Kind of a mixture of a faithful translation, original embellishments and maybe some crips from the English script, but it seems to be a well regarded translation.

There are also up to three fan translations but reports about their quality vary.

Yeah, the soundtrack was my first thought as well. It’s also possible that some of the strategy guides (whether unofficial or not, possibly both?) included the name “Blackjack,” but I don’t have any on-hand anymore to check.

“Dost the wind deliver the humbled voice of mine unto the place thou reside?” rather than “Doth the wind deliver the humbled voice of mine unto the place thou residest?”

They do get it right some places such as:

“Oh my dearest, my beloved, art thou trav’ling far away?” with the correct mode of “to be” for second person singular pronoun, i.e. “art.”

“Then we shalt duel!” reminds me of a line from Infinity Gauntlet where Odin similarly says “we shalt,” again shouldn’t come as a surprise considering Marvel’s love for peppering the speech-patterns of godlike characters with faux-Elizabethan words and often varying grammar, for the rule of cool.

Thank you for noticing this! I’m always dismayed to see Early Modern English endings misused by people who want to sound Shakespeary but don’t know the grammar. These same folks would be embarrassed to use the wrong ending in a modern language like Spanish or French, where subject–verb agreement is a very basic concept.

You guys owe it to yourself to hear the FF Distant Worlds version of the opera if you haven’t yet. http://www.ffdistantworlds.com/album/distant-worlds-music-from-final-fantasy/

Here are the lyrics for the Distant Worlds/More Friends version: http://www.fflyrics.com/ffmf.html

It’s clearly based on the GBA version, but there are a couple of changes. In particular, Draco’s opening bit is totally different and ends with the SNES version’s line.

It makes a change to the play, too. The last verse of Maria’s song comes at the end, after Ralse is defeated. The Black Mages version (which is in Japanese) does that too, even though the new bits added to fill out the story are totally different.

And here are the Italian lyrics from Grand Finale, because why not: http://www.fflyrics.com/ff6gf.html

Mato, in the past you’ve talked about how the worst kind of translation mistakes in games are those that cause incorrect understanding of gameplay and I think it’s interesting how the GBA version chose to keep some of the Woolseyisms in the lines of the opera where you must choose the correct line. (“Oh my hero”, “I’m the darkness”, “Must I/my”). Even though looking at the lyrics we can see you don’t need to preserve those ideas and most of the other Woolseyisms in the song were exchanged for ideas closer to those found in the Japanese lyrics, I suppose for the sake of those who played the SNES version and working on memories of the old lyrics the old lyrics were preserved in those special places for the sake of gameplay so that old-timers wouldn’t be as confused in light of all the new lyric changes. I wonder how many original players skipped through the reading of the script in Celes’ room not realizing most of it had been rewritten!

Oh man, that’s an excellent point that I hadn’t considered!

I’m a big fan of the GBA version of the song. The GBA version was my first exposure to the game and I was blown away by how great the opera was in that version. Not only did they do a great job matching the lyrics to the music, but they also just straight-up sounded great and poetic and very fitting for an opera. I actually made a separate save file on my GBA cart where i saved right before that scene so i can rewatch it whenever i want. Later on, I looked up the SNES version on youtube, and not only did i feel the lyrics were worse, but i also noticed that the digital “voices” sound a lot more like real voices in the GBA version then in the SNES version. Then I later found this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MU3Prg4pC-s which i actually now have on a mix CD in my car.

The whole issue of translating songs reminds my of how Funimation used to do that with anime opening and closing songs. Some of the big ones i really loved were various Dragon Ball series (original, GT and Kai, but sadly not Z) and the first three seasons of One Piece. I actually prefer the english versions of the songs from those shows over the original japanese versions, mainly cuz i can easily sing along.

Actually Mato, you mentioned in this article doing some song translations in the past, and I know you’ve worked with Funimation. Have you done any of those Dragon Ball or One Piece songs?

Yeah, I’m pretty sure I did some for both, but I don’t remember which ones specifically. Especially One Piece and its 8000 different intro and ending songs 😯

You’re right to say the fan translation of the opera doesn’t quite fit the music. It’s got less syllables than the Japanese version, for one, though that can kinda be fixed by dragging some syllables out over multiple notes. But even then there’s a lot of weird stresses happening, emphasis being placed on the wrong syllables, pauses in the middle of words, that kind of stuff.

For example, looking at the two full lines of the first part (minus the Marias):

Generally, if you’re putting lyrics to music, it’ll sound most natural if a) the syllables with the most stress match up to the most emphasized notes in a phrase (a section of the melody), which are usually the highest (if you’re going up), the lowest (if you’re going down), or the longest-held notes, and b) each phrase is a complete thought. So, if you look at the melody these lyrics need to be attached to, you can divide it up into phrases like this, where the capitalized letters are the most emphasized notes:

e f G c / e f G

g g A c / c e D

a b c D / G b A <- the last section has two emphasized notes, but the second is stronger, since it's the last one in this melody.

While it's generally acceptable to add or subtract syllables when you're translating lyrics (either holding syllables across multiple notes, or by hitting one note multiple times), most people seem to aim for same number of syllables as the original. The GBA translation manages to both have the same syllable count AND get all the stressed ones on the right notes, which is actually really hard. So I'm not surprised they use it for performances!

My be-LOV-ed / do you HEAR

My words WHIS-pered / in your EAR

As if I WERE / BY your SIDE?

Meanwhile, there's two ways I can think of to divide the fan lyrics, and neither of them really work.

Dost the WIND de- / liver THE

hum-bled VOICE of / mi-I-ine

un-to the PLACE / THOU re-SIDE?

Dost the WI-ind / de-li-VER

the hum-BLED voice / o-f MINE

un-to the PLACE / THOU re-SIDE?

The first one is worse, since the first line manages to divide 'deliver' in half across phrases, end both phrases weirdly, and put emphasis on the wrong syllable ('the'). Not to mention dragging 'mine' out across three notes in the second line sounds kinda weird. The second one at least gives every phrase a complete lyrical thought, but 'wind' and 'of' are both too short to sound good hitting multiple notes like that, and 'deliver' and 'humbled' have the stress on the wrong syllable. The last line is the only one that fits the music nicely.

You can do this for the entire song, and you'll generally find the same results: the GBA version matches the syllable count and stress almost perfectly, with just a couple minor oddities, while the fan translation is a decent poem but just doesn't match up to the music very well; the second part is fine in some spots, but sacrifices a lot of the rhyming, which is unfortunate. The SNES version, meanwhile, needs a lot of the note-to-syllable adjusting that I mentioned earlier, but the stresses work, so the second part at least can be sung! The first and third parts, though, just shorten a lot of the lines too much to fit the whole melody comfortably.

That was a fairly simplified explanation, but hopefully it makes sense! (and apologies if I got some of my terminology mixed up, it's been a long time since I touched musical theory and even longer for poetry)

Essentially, what I was getting at is that the SNES version (at least in part 2) has the same stresses but different syllable counts, the fan translation has the same syllable counts but different stresses, and the GBA version manages to get both.

(and wow, I didn’t realize how long that comment was when I was writing it…)

Ahhh, this is super interesting! Thanks for sharing this knowledge 😀

After reading this article, I was going to make a similar comment, so thank you for writing this out with more detail than I could have. As a linguist, I wanted to follow up that a difference between English and Japanese (or between any two languages) that can present difficulty in translating songs is information density. This is the average amount of information carried per syllable. To give a quick example, one Japanese word for you, [anata] has three syllables, while English “you” only has one; thus you would need more syllables to get across the same concept in Japanese, indicating a lower information density. This is basically true of Japanese and English more generally; Japanese has a lower average density than English. This is partly due to the smaller number of possible sounds and greater number of syllable constraints in Japanese. For instance, Japanese has only five vowels, while English has quite a few more, and Japanese syllables must end in vowels (or nasals, usually transcribed as “n”).

Anyway, all this means is that you generally need more syllables in Japanese to get across a similar idea. To compensate when translating from Japanese to English, you may need to punch things up a bit to get to the right syllable count. When translating from English to Japanese (something I’m not an expert on), it seems it can be tricky to adequately slim down the syllable count. For examples, I definitely recommend watching some Japanese dubs of Disney songs on Youtube! Some of them do a good job, while others (such as “Hellfire”) are awfully… wordy.

This is one of the key things I was wanting to fix with my FF6 Improvement hack for the SNES version, years back. The opera scene is so poignant, and yet the lyrics never matched up with the music. It was a month of using FF6Edit to nudge the timing opcodes into the right sequence, but once I did I was amazed at how much this synchronization added to the impact of the scene.

There is a new “ROSE” improvement project that picked up where I left off and (I think) finished my work on this. I’m almost to that point in the game, and I’m excited to see if they carried it forward!

Ah, this brings back some fond memories.

I played the game when I was 14 with a famous Italian fan translation.

And you know what? They used the official Italian lyrics of “Aria di mezzo carattere” for this scene.

Classy touch. I should play the official GBA translation to check how they handled it.

By the way, thanks for the great article!

Another cool thing about the official translations of the opera is that The Black Mages (ie, Uematsu’s FF rock band) cover of the song (and their third album) is actually called Darkness and Starlight https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iBTmopsDJNk

How cool is that?

My brother and I were both alarmed when we read that the name Blackjack isn’t in the game, but after a brief concern that we’d shared a psychic experience with an SNES game, I remembered that we had inherited a strategy guide from our dad’s friend along with the game, and the character profiles and maps of areas, Blackjack included, told us its name.

I was mildly obsessed with Setzer and very excited to learn that detail about him at the time, but over 25 years it just felt like obvious information. I forgot how I learned it until now!

I played through FF6 a little bit late. I had heard about the famous opera scene, and was really looking forward to it. I finally got there, and… it didn’t disappoint! I thought it was great. So I went to talk about it.

“Oh man, it really was as great as you guys said. That scene was hilarious!”

“What?! Hilarious? No, no! It’s supposed to be one of the most moving and touching scenes in the game!”

…I was a little puzzled. I mean, it’s a goofy melodrama that you’re forced to act in that has no bearing on the overall plot, you can screw it up with ridiculous lines, and an octopus attacks in the middle of it. I… seriously thought it was supposed to be a comedic scene. Honestly, to this day I’m not sure I’m wrong, and am wondering if the people I was talking to were taking it more seriously than it was taking itself…

“Mezzo-carattere” is a technical operatic term that means half-character, i.e. half-serious and half-funny.

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/mezzo_carattere

You were correct to laugh at it. Others were also correct to take it seriously.

I am in disagreement with a lot of fan renditions of the opera that completely leave out the half-funny part of the opera. There has to be an octopus falling from the rafters, that’s the grand finale!

To be clear, “Mezzo Carattere” doesn’t refer necessarily to whether the role is funny or not. In opera, singiners have main voice classifications (Soprano, Mezzo, Tenor, Bass) which indicate general range, and also subclassifications (Coloratura, Dramatic, Lyric, Character, etc.) which indicate what you sound like within those ranges. Hitting the notes with good technique is valuable, but roles are often also written for specific sound, so the right subclassification matters, as well.

“Character” singers have undefined voices, usually carried by young singers whose voice hasn’t developed a specific sound. Voices change over time; for example, in my early 20’s, I was probably a character tenor. My voice used to be really light and agile. Now, in my early 30’s, I’m definitely a dramatic tenor. My voice is weighty and loud as hell, and if I try to sing the music that was appropriate for me in my 20’s, it just sounds stupid.

The definition for Mezzo-Carattere is partly right, because “character” singers usually do comedic roles (This is because their voices are unrefined and adaptable, usually good for singing in silly voices or accents). But, if you want to understand the “Character” voice subclassification better, here’s a good article about it:

http://choirly.com/character-soprano/

“Mezzo Carattere” is likely just a low-singing character soprano. It’s hard to say, because it’s not really a recognized voice type these days. If I had to take a guess, it would probably be Spinto Soprano, which is basically just a character soprano with a deep voice.

As mentioned before, character/spinto classifications are usually due to age and general lack of development due to being young. No one stays a character/spinto for their whole life. Calling Celes a “Character Mezzo” is appropriate, given her in-game age is supposed to be 18. Spintos typically develop into Dramatic subclassification (really, really big voices with lots of power and not as much agility.)

Here are some examples of Dramatic Mezzos, to give you an idea of what Celes might sound like (picture slightly younger, tinnier; but the implication is that with time and practice, she’d probably sound similar to this):

Leontyne Price: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-yAW1gpP2o

Elina Garanca (skip to about 1:15): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GD63RuQduc

I was watching the Funky Fantasy IV stream, and noticed how the google translation changed day to day. was wondering if you are using a fully g0ogle-translated script from a specific day? Or is it parsed live on stream?

Mato, I have a question for you. This translator says that the opera is where Celes starts using feminine language and that she maintains her usage of feminine language for the rest of the game:

http://kwhazit.ucoz.net/trans/ff6/25opera.html

Can you comment on this?

I just skimmed a bit of her earlier and future dialogue, but it seems this is at least the point where she starts using the sentence-ender “wa”. Apparently the way she talks changes a bit throughout the game, in the beginning she was addressing others as “omae”, but she’s switched to “anata” by the time they reach Zozo.

Might be worth a sub-article on its own, actually.

I learned the name of the airship from the game guide. Also I was using this as a user name BEFORE then!

The Google Translation of the fired line has a couple different ways to read it. 😀

Sill Google, you can’t be fired without being hired first.

Or by fired, does it mean we’ll be catapulted like was mentioned in the previous section? 😉

The French translation by and large is extremely good (Square Enix have been doing an incredible job for Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy since around the same time their English translations started getting reliably high in quality, especially since FF7 was notoriously translated into other European languages from the English version, retaining all that version’s issues and introducing new ones). Anyway, the French airship line (from the Android version, which I believe is the same translation):

“L’empire nous repérera rapidement si nous survolons la capitale. Atterrissons un peu plus loin.”

Which literally translates into “The Empire will spot us quickly if we fly over the capital. Let’s land a little further out.”

For some reason, my memory of the Aria ever since the 90s has Celes’ voice being at least an octave higher than in the actual game and whenever I play it or listen to the soundtrack her relatively low voice throws me off for a moment.

About Setzer’s motivation in the original game, I always assumed it was yet another reference to Star Wars, namely to Lando Calrissian. Like Lando, Setzer was also a gambler and playboy who originally worked alongside the resident evil empire only to switch sides to the rebels as the plot went on.

Long time reader, first time poster – Thanks for providing a place for folks to dig into such a memorable gaming experience.

Just because I haven’t seen it mentioned yet, I highly advise folks to check out Jake Kaufman’s Impressario fan creation from the Balance and Ruin fan album: https://ocremix.org/remix/OCR02699 (don’t forget about the Lyrics tab!)

This is great example of taking creative liberties to drive different tone (more italian opera, plus you know… Queen) but to also preserve some translated lyrics and call back to the original source material.

I haven’t listened to it in years probably yet it still played in my head clearly when you mentioned it.

The translation of poems and songs and such is one of the most impressive feats in translation I could think of. That it’s even possible for a poem translation to remain a full-fledged poem, in the same style of the original, and still get the original meaning across (even if the wording has to be changed heavily at times) is mind-blowing. A few years ago, I read a German translation of Orlando Furioso and whenever I stopped to think about what I’m actually reading, the translator seemed nothing less than a magician to me.

Granted, that’s probably also because I’m utterly hopeless when it comes to poems and could never write one myself. The idea of “converting” a poem into something with the same meaning is pretty much alien to me. Even reading poems gives me trouble. That I managed to read a lengthy narrative poem from 16th century Italy in a German translation from the first half of the 1900’s without getting too lost is arguably very impressive in itself.