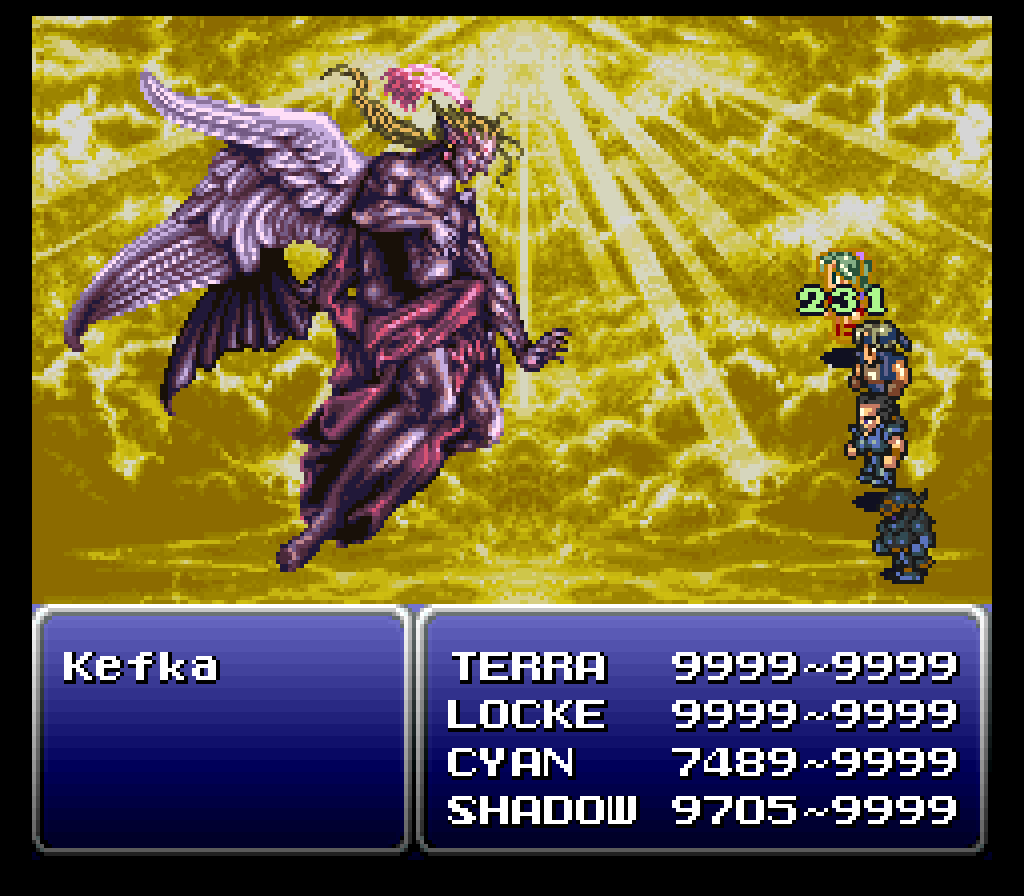

This is part of my ongoing series in which I compare four translations of Final Fantasy VI with the original Japanese script. For project details and my translation notes from Day 1, see here.

Part 4: Imperial Camp to Veldt

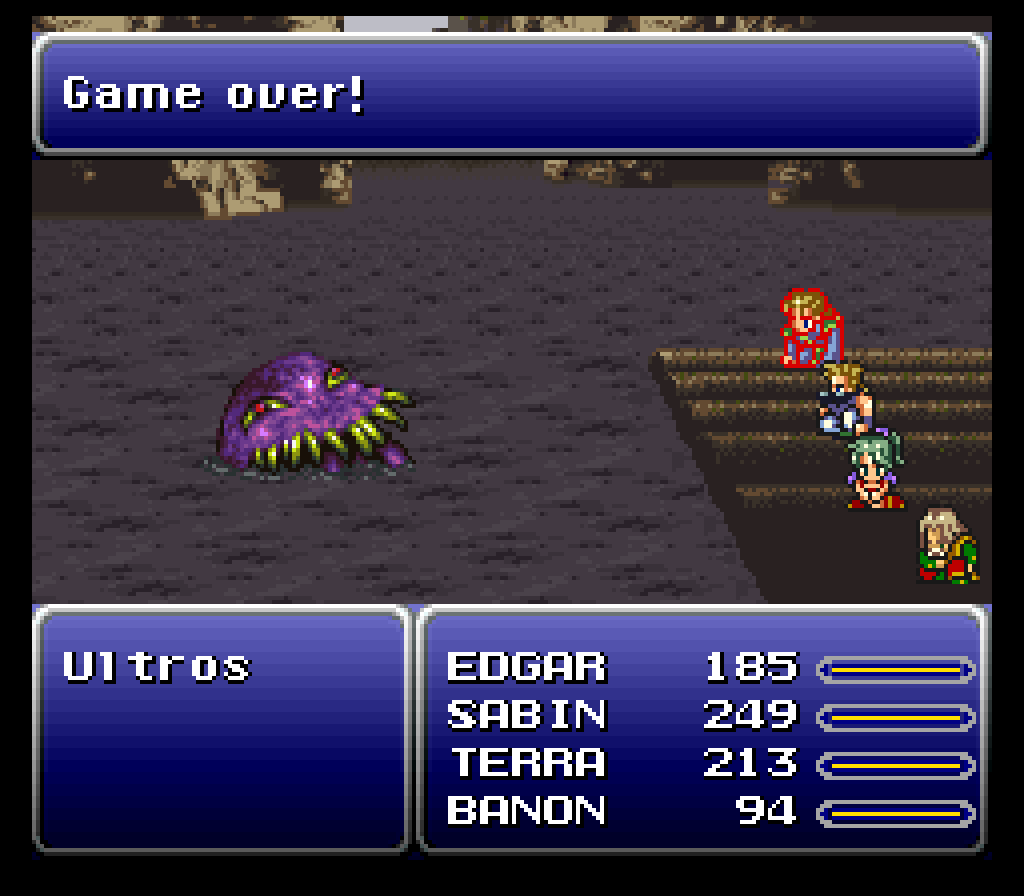

This segment of the game features a whole bunch of memorable scenes from Final Fantasy VI – you got the Kefka craziness, General Leo’s debut, Cyan’s introduction, the Phantom Train, Cyan losing his family, and more. Naturally, our list of translation notes wound up really long this time around.

Video Archive

Notes

I’ve listed some of the translation highlights from this section of the game below, but as always, I cover so much more during the actual stream. So if you want to see me nitpick things line by line, check out this day’s video above.

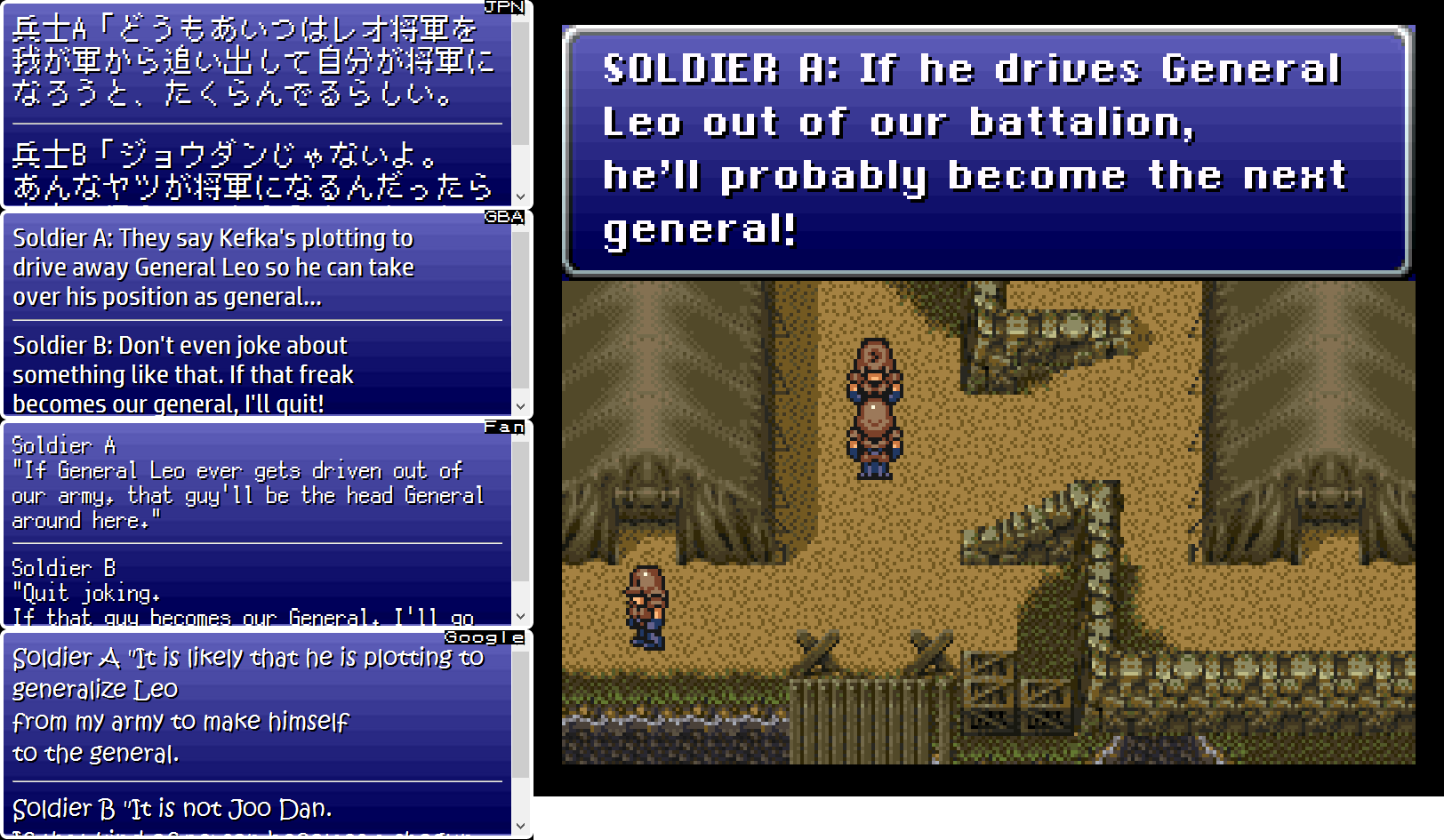

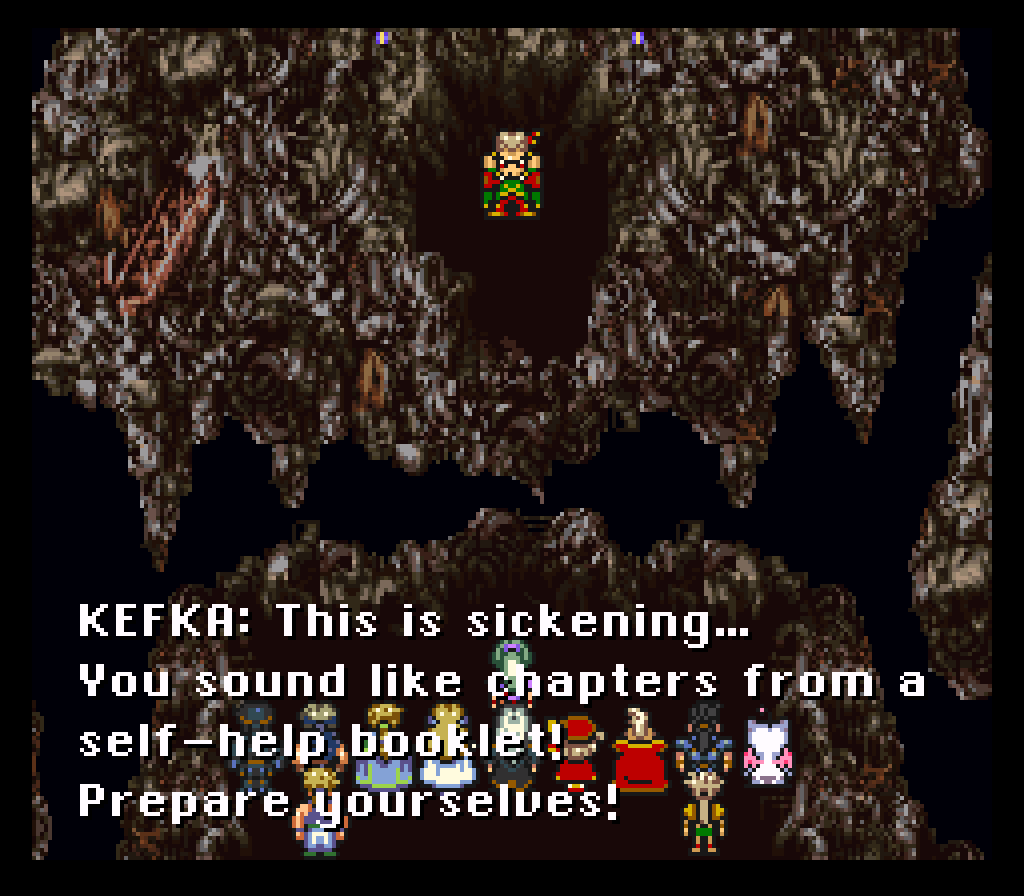

Kefka’s Evil Plot

In the Japanese version of this line, this soldier says, “Apparently he (Kefka) is plotting to kick General Leo out of our army/battalion and make himself general.”

This is significantly different from the Super NES translation, because it indicates that Kefka is actively scheming in order to take over. I hadn’t put it together before, but this seems to explain why General Leo conveniently receives a message to return to the Empire, after which Kefka immediately takes charge and kills an entire kingdom of people. Until now, I had always assumed that everything during this scene happened at precisely the right time by sheer coincidence.

We can also see that the fan translation alters the original line in precisely the same way the Super NES translation does.

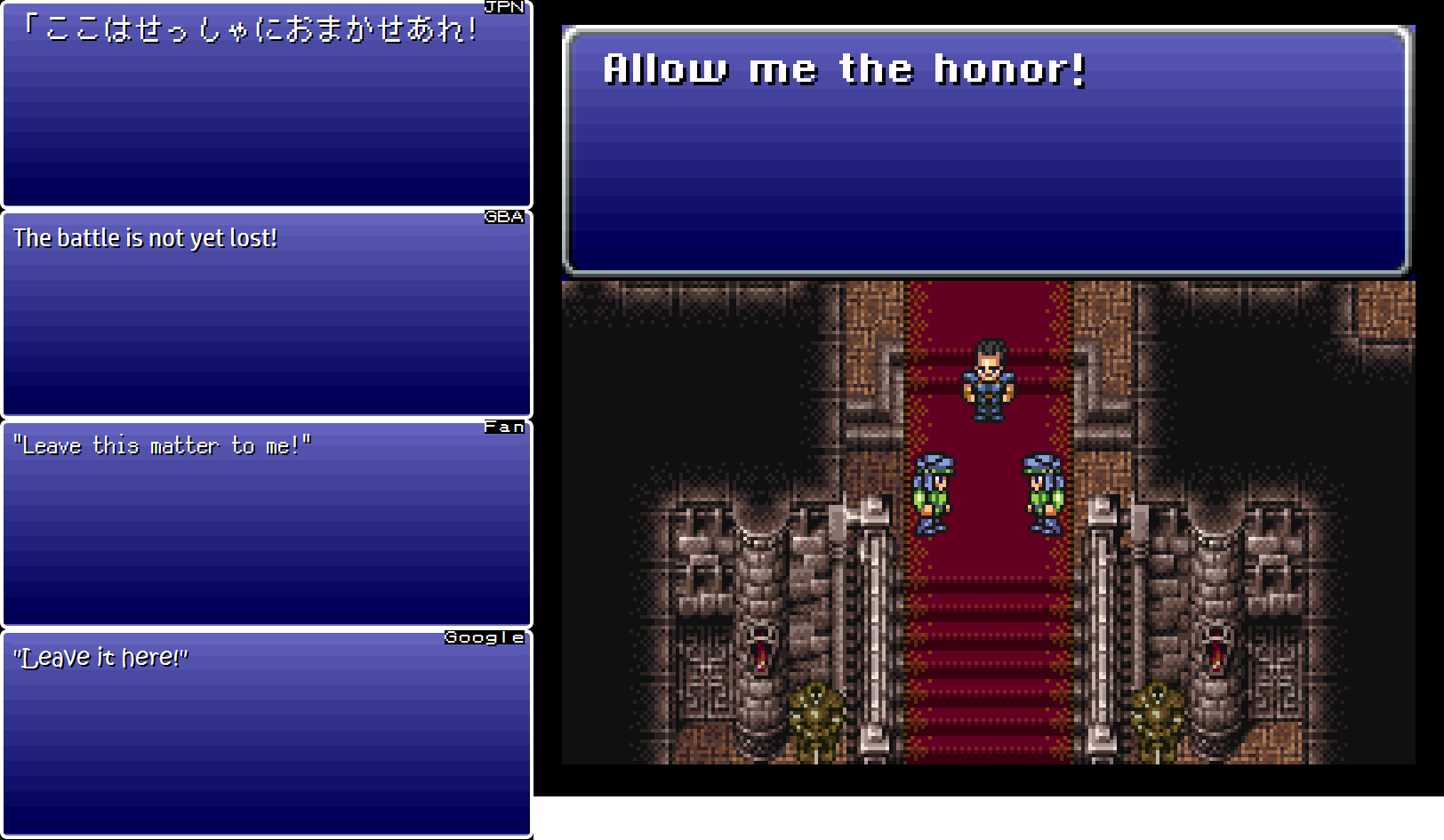

Samurai Style

There’s an honorable samurai named “Cayenne” in Final Fantasy VI, but due to name length restrictions this name was shortened to “Cyan” in the Super NES translation. As a result, I think many English-speaking players pronounce his name “sigh-ann”, like the color “cyan”. In Japanese, though, the first letter in his name is meant to be pronounced like a “K” and not an “S”.

Anyway, in Japanese, Cyan speaks in a very heavy, samurai-esque style of Japanese. No one in real life talks this way, so unless you’re accustomed to the quirks of this speech style, it looks like a bunch of nonsense. It’d be like if you asked a Japanese kid who’s just started studying English to translate Shakespeare quotes.

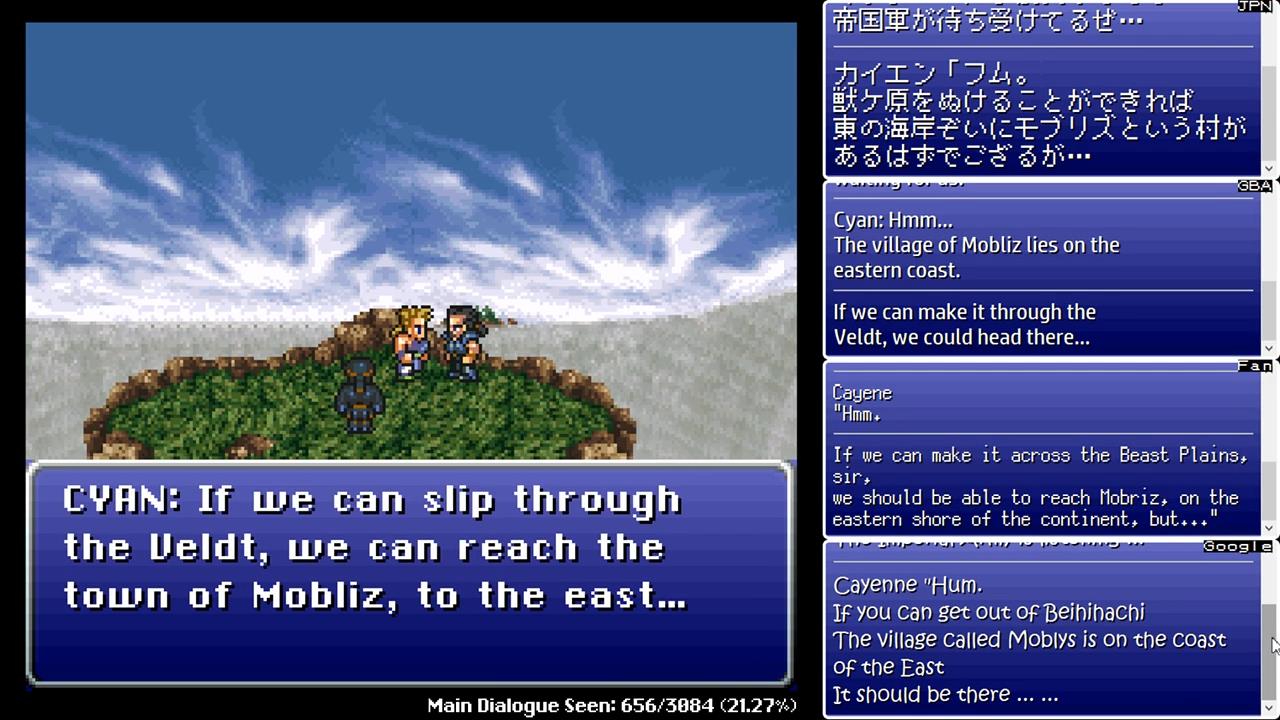

As a result of this unusual speech style, both the fan translation and the machine translation tend to struggle whenever Cyan speaks throughout the game. They aren’t bad in the screenshot above, but I thought I’d mention it ahead of time, before we start digging into more of Cyan’s lines later on.

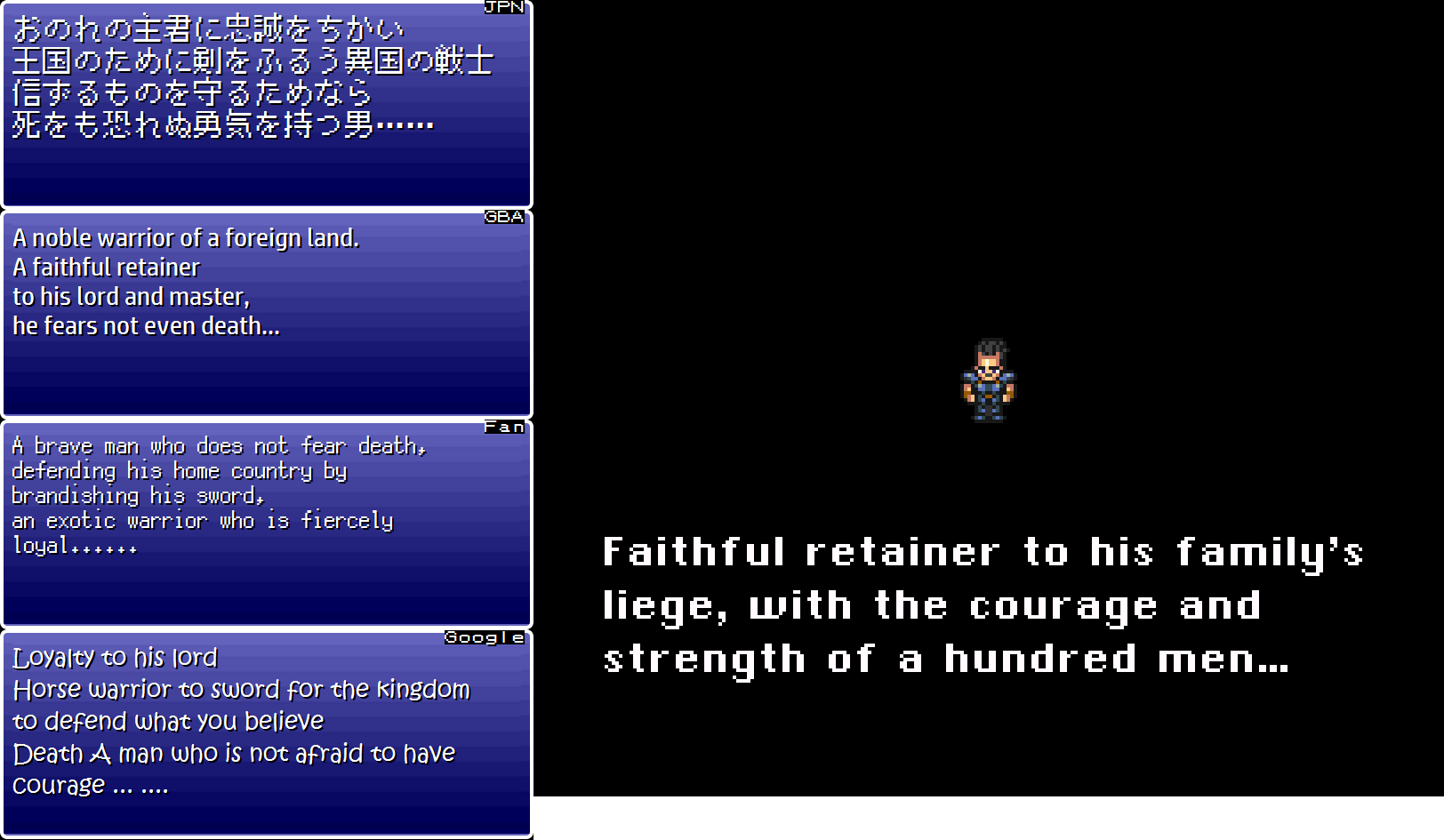

Cyan’s Introduction

As we can see, Cyan’s introduction in Japanese is quite a bit longer than the Super NES translation, and looks kind of complicated in general. The Japanese version sounds kind of clunky in a literal, word-for-word translation, though – it’s something like: “A warrior of a foreign land who has pledged loyalty to his lord and wields his sword for the sake of the kingdom. A man with the courage to not even fear death if it’s for the sake of what he believes in.”

The Super NES translation sort of pushes Cyan’s Japanese introduction to the side comes up with something mostly new. The GBA translation is a mix between the Japanese version and the SNES translation, and the fan translation tries to stick closer to the Japanese text but stumbles in a few places. And the trickier-than-normal writing causes Google to stumble a bit more than usual as well.

Until now, I had never really considered Doma to be some far off, somewhat exotic land. I guess that’s because it wasn’t really represented that way in the Super NES translation’s text.

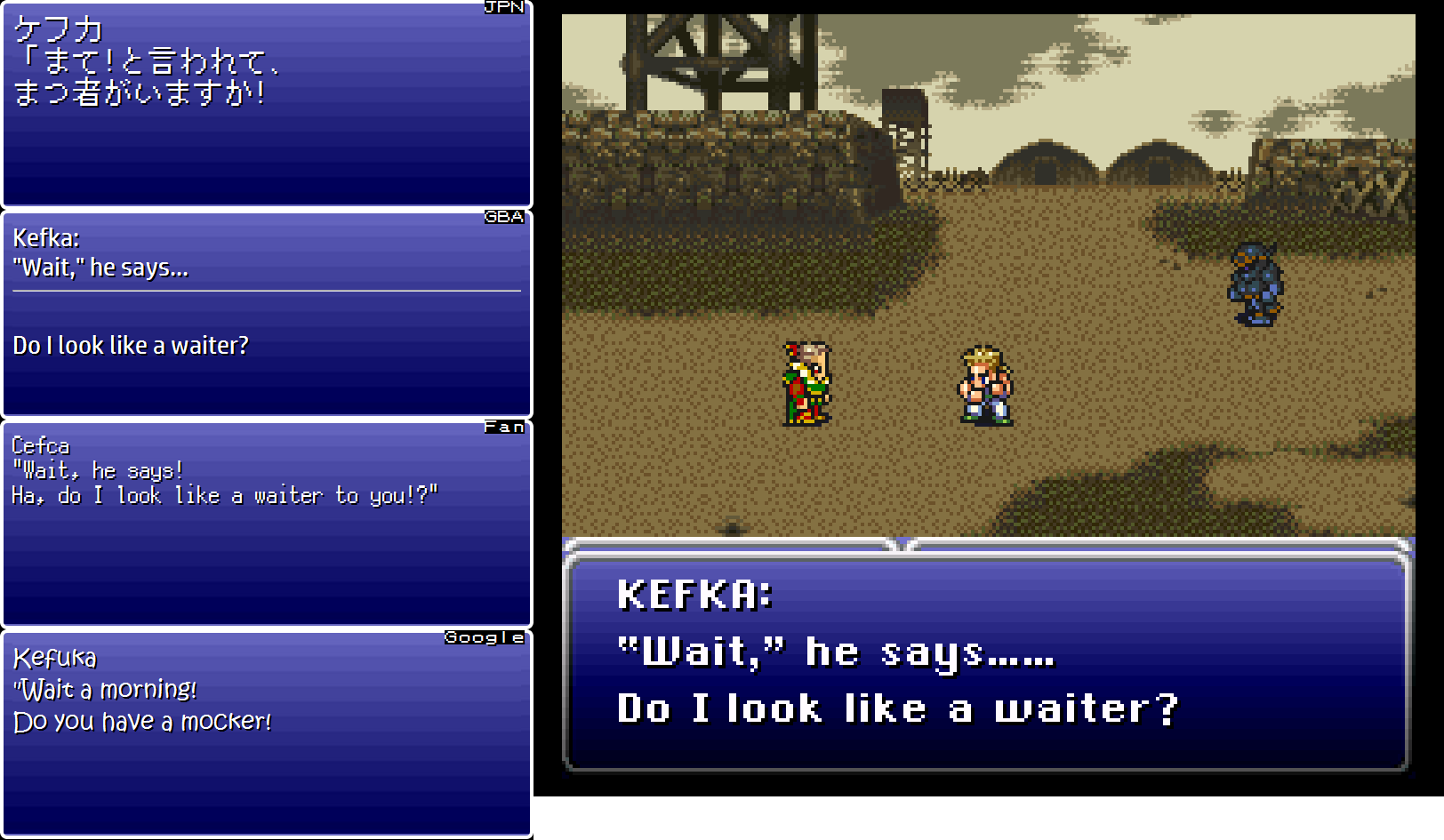

Kefka the Waiter

Sabin challenges Kefka to a fight. Kefka quickly tries to run away, so Sabin yells, “Wait!”. In response, Kefka says in the Super NES translation:

”Wait,” he says…… Do I look like a waiter?

This is a pretty popular quote from the SNES translation, which is why it appears as-is in the GBA translation too. The actual Japanese line is closer to:

As if there’s anyone who actually waits after being told to wait!

The fan translation clearly didn’t stick to the original Japanese script here, however. Instead, it too pulls from the Super NES translation but changes it ever so slightly for some reason. I have no idea what happened to Google here.

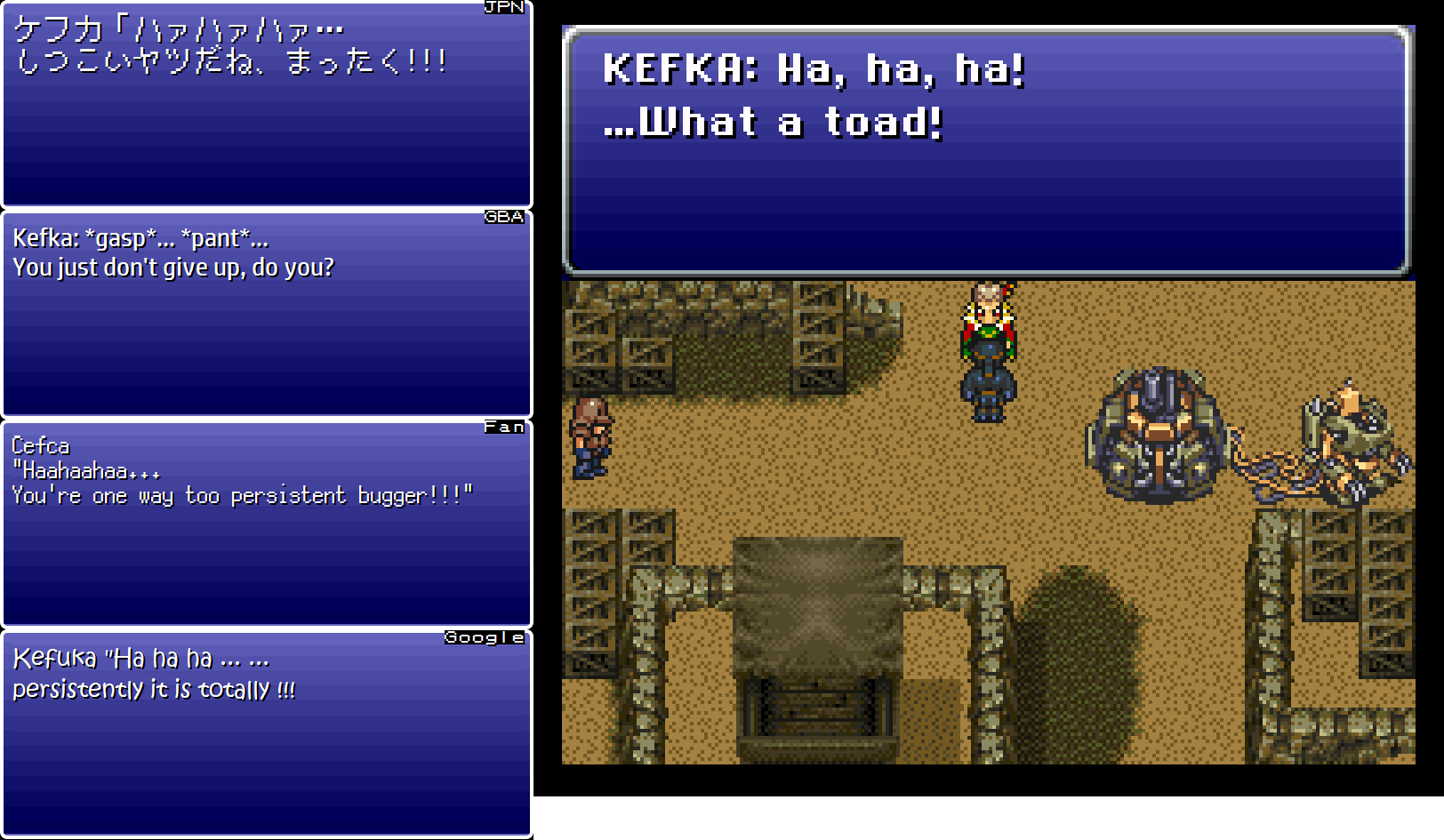

Panting ≠ Laughing

Kefka runs away from the battle. After Sabin catches up again, Kefka says in the Super NES translation: “Ha, ha, ha! …What a toad!”.

If I hadn’t checked the Japanese version side-by-side like this, I never would’ve realized that this translation is completely wrong. Instead of saying “ha ha ha”, Kefka is actually out of breath here from running, and is making a panting or wheezing sort of sound.

As I’ve pointed out in the streams so far, the simple Japanese sound “ha” – and some of its variations – have a surprising number of meanings depending on the context. In this case, it appears the Super NES translator didn’t have the full context when translating this line.

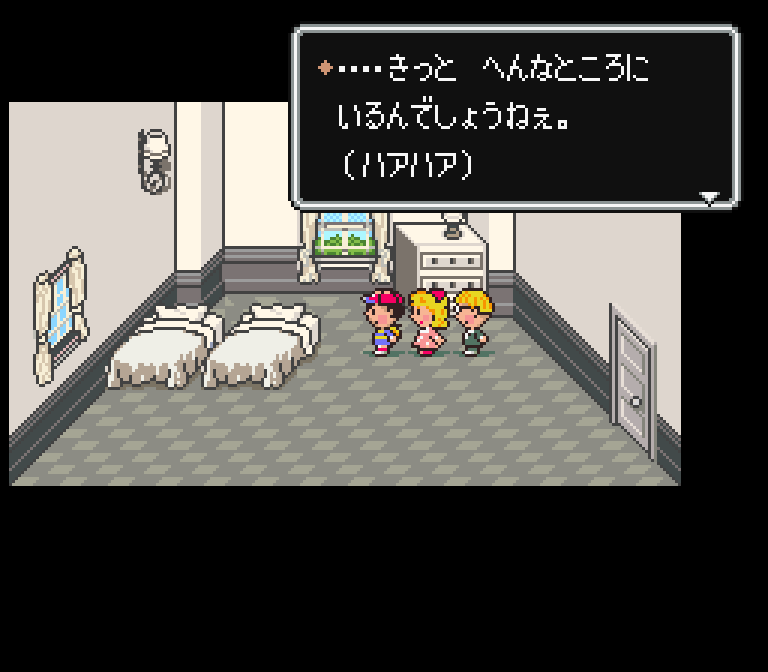

This “gasping is mistaken for laughing” mistake isn’t an isolated incident, though. A related example that immediately comes to mind is from EarthBound – in the English version, the item delivery guy will call you on the phone and make weird laughing sounds if he can’t reach your location. But in Japanese, he’s actually out of breath after running all over the place trying to find you.

|  |

| MOTHER 2 has elongated 'hā' sounds indicating labored breathing | EarthBound has a representation of labored breathing that's more associated with laughing |

The Super NES translation also has Kefka say “What a toad!”. In Japanese, this line is simply something like, “Geez, you’re a persistent guy!”. He says this because Sabin won’t stop chasing him.

Out of all the translations, it looks like only the GBA script properly handles this entire line.

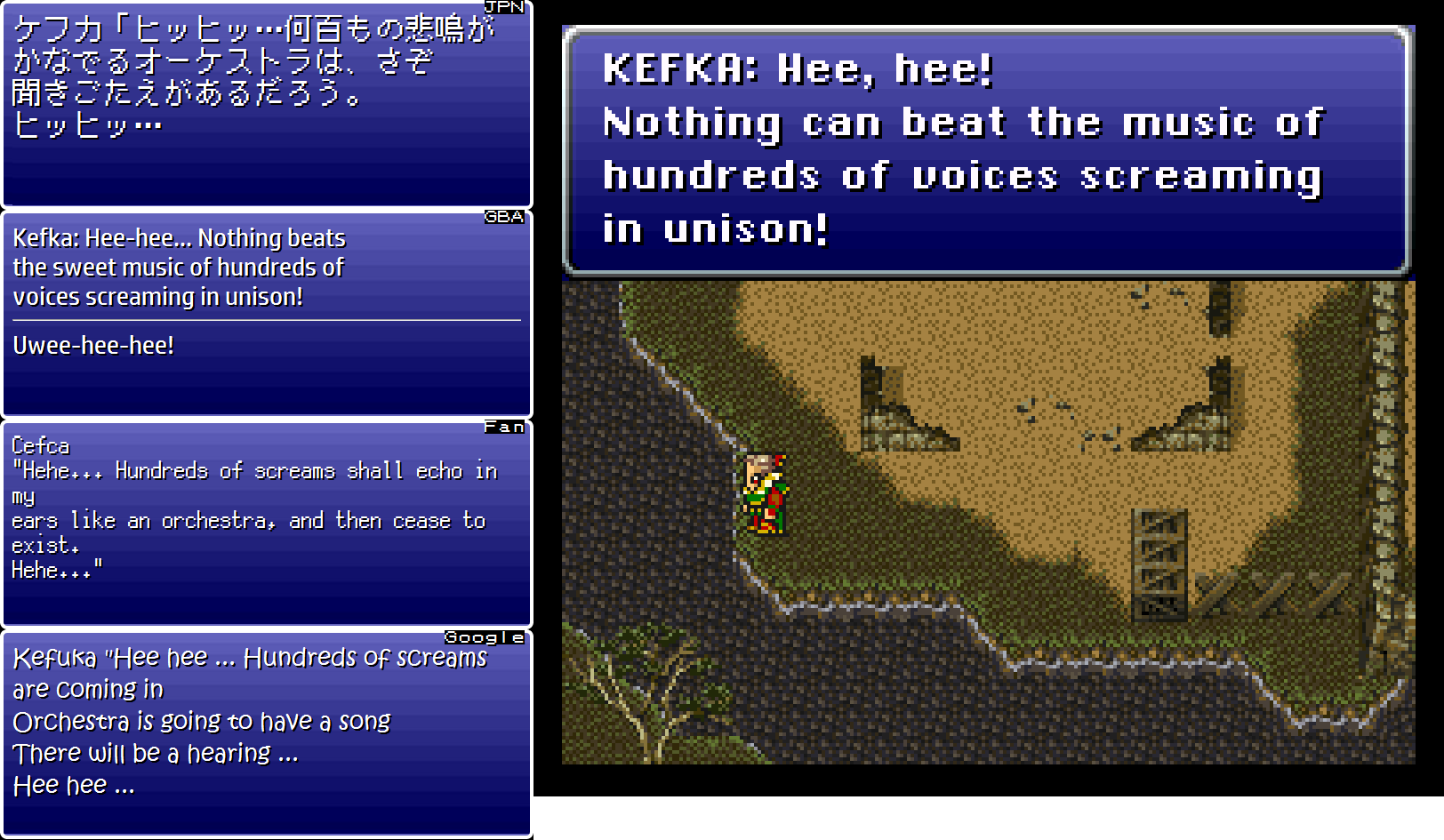

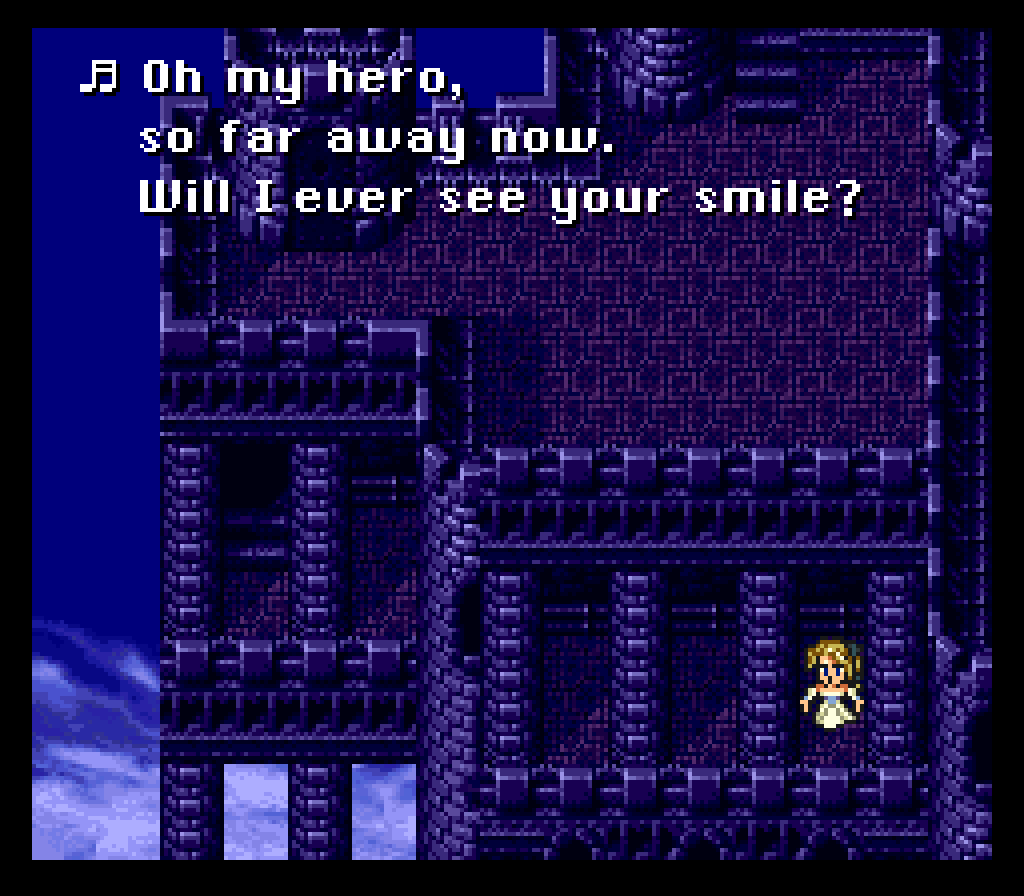

Symphony of Screams

As Kefka poisons the water around Doma Castle, he roughly says in Japanese, “Heehee… I bet an orchestra of hundreds of screams will sound wonderful. Hee hee…”

The GBA translation stays close to the Super NES translation but not exactly. The fan translation sort of misses the point – he just sounds generically evil here, but the line is supposed to sound more like that of a psychopath. Besides that, the translation is incorrect anyway. I feel like the translator recognized some of the key words but didn’t fully grasp the grammar that connected them.

Also, in Japanese, I feel that Kefka is looking forward to learning what it sounds like, while in most of the translations it sounds more like he’s already familiar with the sound.

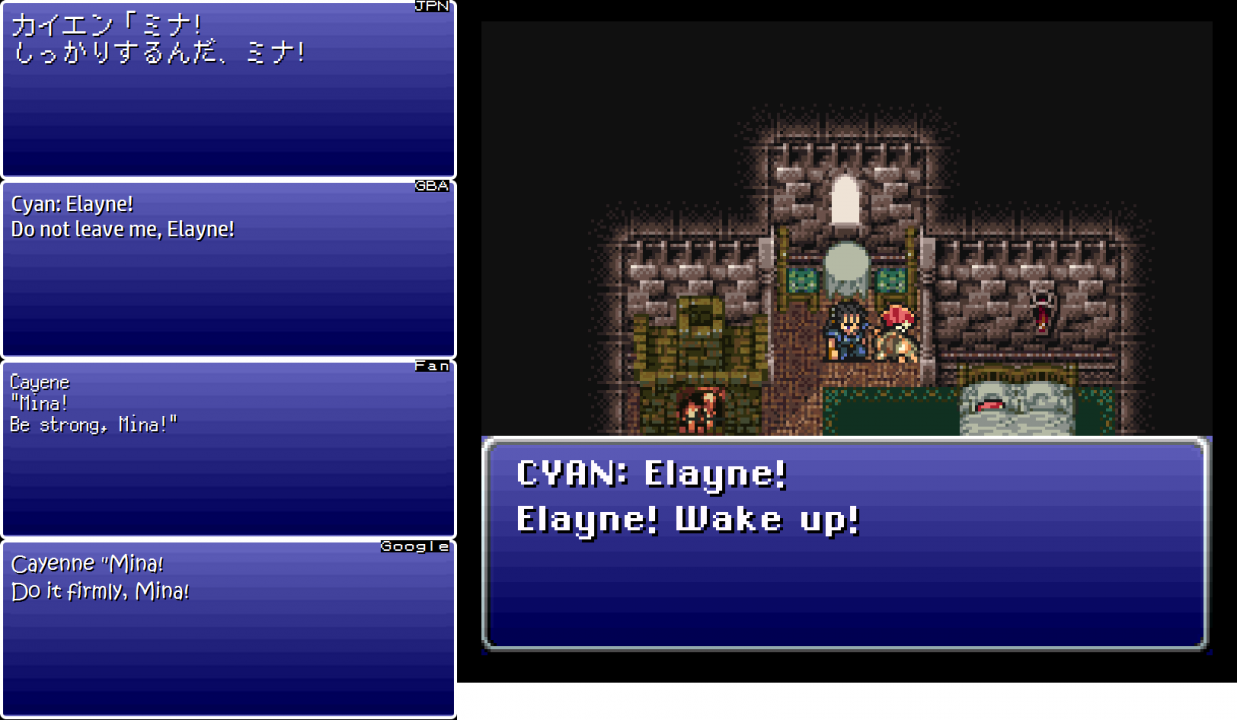

Family Names

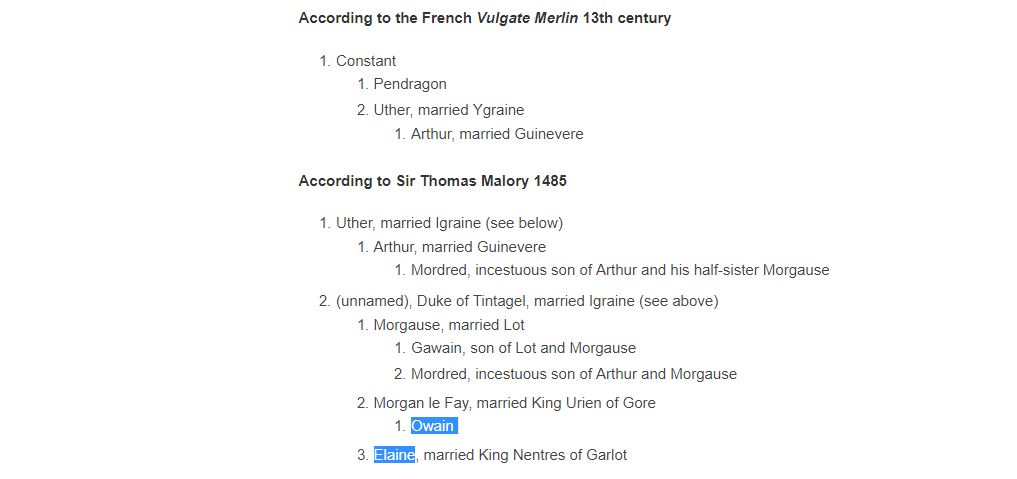

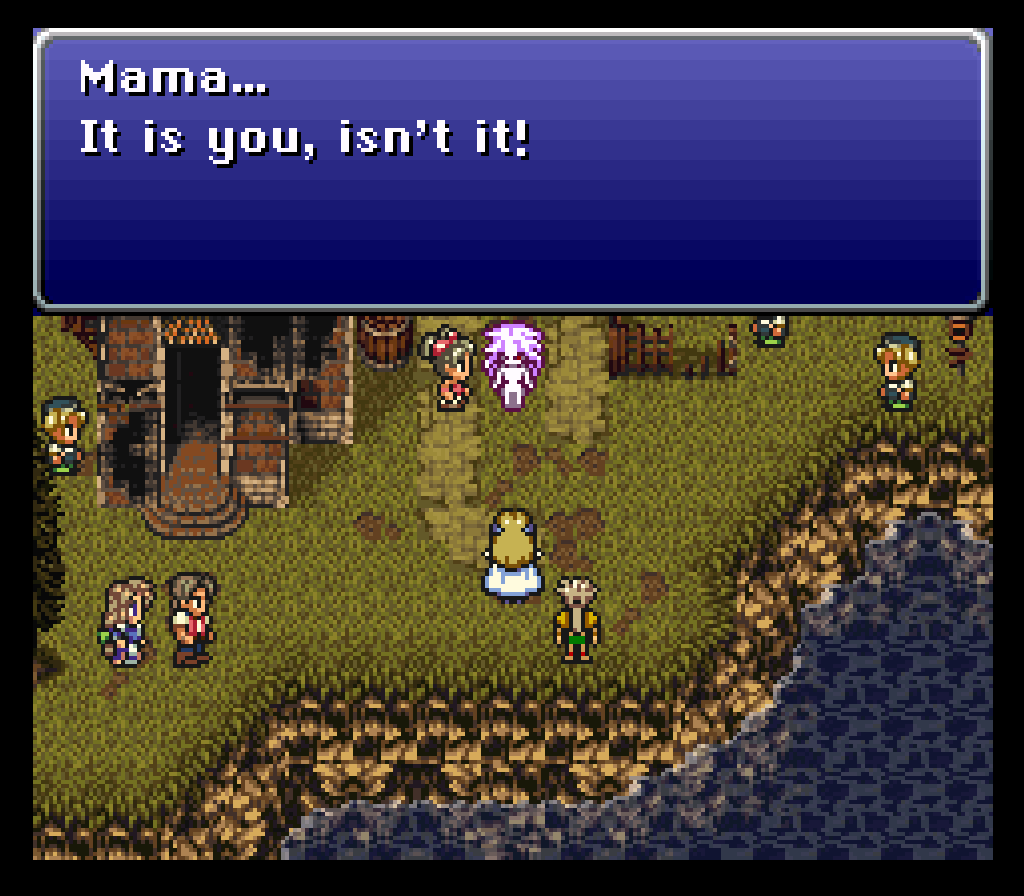

Cyan’s wife and son are known as “Mina” and “Shun” in Japanese. In the Super NES translation, these names changed to “Elayne” and “Owain”.

I’m not really sure why the names were changed, but I think the “Mina” and “Shun” names are meant to give off a “people in this exotic land have different-sounding names” vibe. The names are very Japanese-sounding, and since Cyan is called a samurai in some official materials, it all fits. But when I think about it, a samurai called “Cayenne” doesn’t really fit as well. Weird.

I’m not sure where the “Elayne” and “Owain” names come from and what thought process was behind the name change, though. The names sound vaguely familiar from my high school English classes, and after a quick Google search it seems like they might be a reference to the King Arthur legends:

I barely remember the details of the legends though, so maybe I’m just grasping at straws here.

In any case, the GBA translation retains these new names. The fan translation goes with the name “Shyun” for the son. This isn’t a typo, though, it’s just an alternate way of spelling “Shun” – see my article about common problems writing Japanese words in English for some more (and entertaining!) info.

Given that “Shyun” isn’t how most Western learners of Japanese would spell the name, I’m guessing that the fan translator found a Japanese guide or some sort of secondary material that included the “Shyun” spelling in it.

Cyan’s a Mechanical Klutz

Cyan goes berserk and can only think of destroying the Imperial troops out of revenge. At one point, Cyan jumps into a suit of Magitek Armor. Shortly after, he runs over numerous Imperial soldiers at high speed. In the Super NES translation, he yells, “We can’t stop now!” as he plows through a bunch of soldiers.

I always thought Cyan shouted this line because he was really angry and out for revenge. But it turns out it’s a mistranslation – in Japanese, he actually shouts, “I cannot stop it!” in his unique samurai speech style. So when Cyan runs through the enemy soldiers, it’s not because he’s super angry, but because he doesn’t know how to pilot the Magitek Armor.

This also fits perfectly with Cyan’s aversion to machines. In fact, this scene is apparently where that machine-related ineptitude first appears. Until now, I had never connected any of these things, so I’m glad I finally looked at the translation and original script side by side like this.

The Forest of Many Names

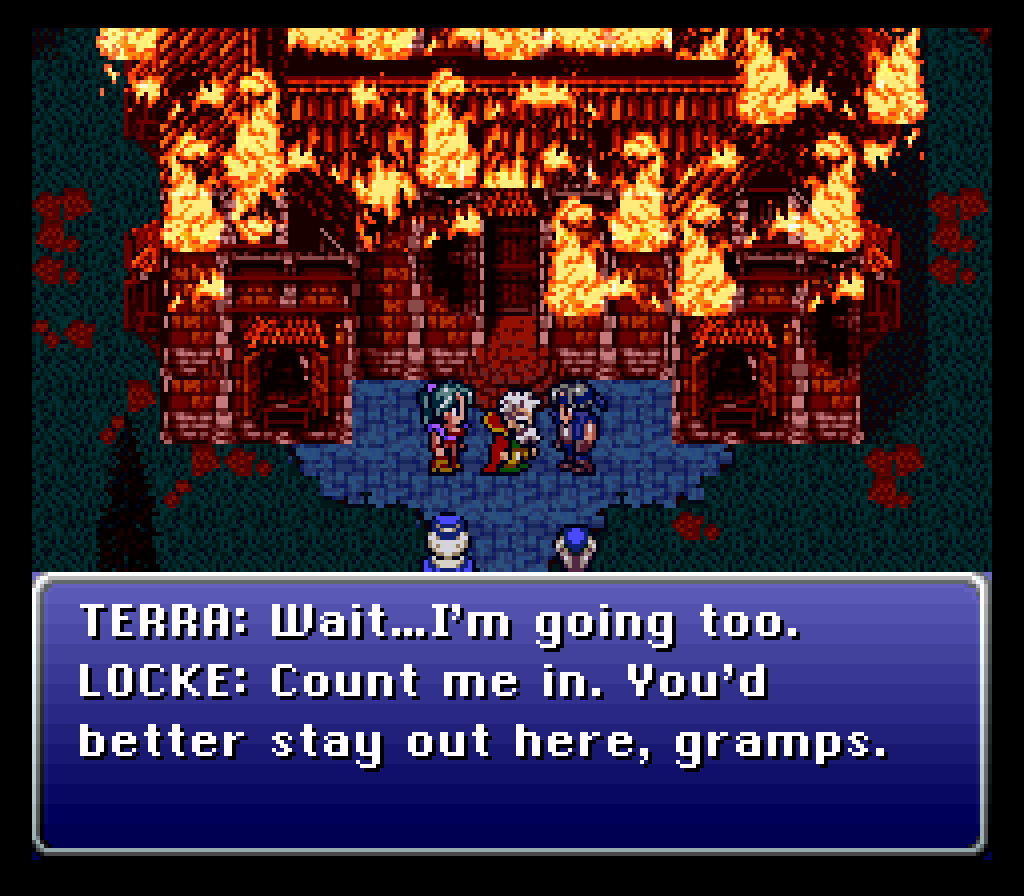

Eventually, Sabin and Cyan team up and try to find a way back to Narshe. Doing so requires them to pass through a spooky forest, though.

In Japanese, the forest is called the 迷いの森 (mayoi no mori), which can be translated in dozens of different ways. It’s actually a really common name in Japanese entertainment – the Zelda series calls it the “Lost Woods”, Super Mario World calls it the “Forest of Illusion”, and the Pokémon series calls it the “Lostlorn Forest”, “Wandering Woods”, and “Bewilder Forest”.

The Super NES translation of Final Fantasy VI goes with a unique solution for this tricky name: “Phantom Forest”. Although the forest does have a sort of Zelda-style Lost Woods maze-iness to it, the forest is filled with ghosts and it eventually leads to a ghost train, so the SNES translator chose a forest name that uses this paranormal theme.

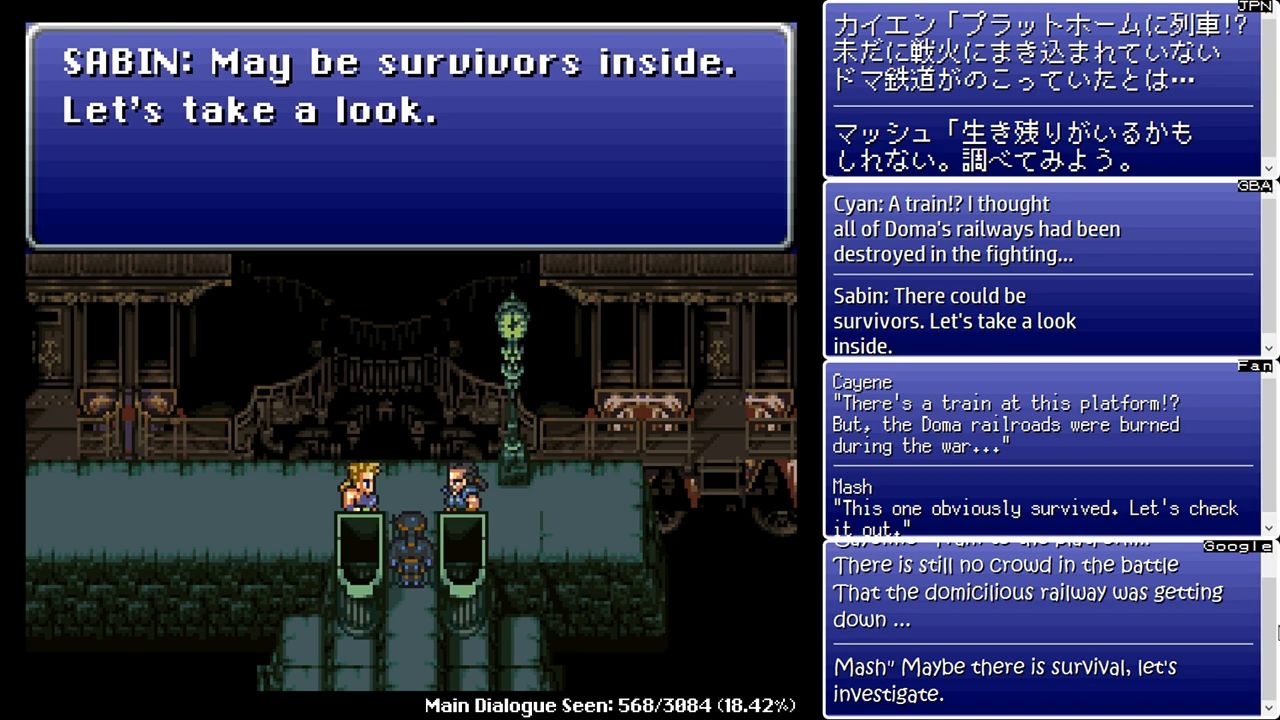

Doma Survivors?

Sabin and Cyan find a strange train in the forest. Sabin suggests there might be survivors from Doma Castle nearby. It’s a very basic line that has nothing tricky in it at all, but the fan translation makes multiple Japanese 101-level mistakes and gets it completely wrong.

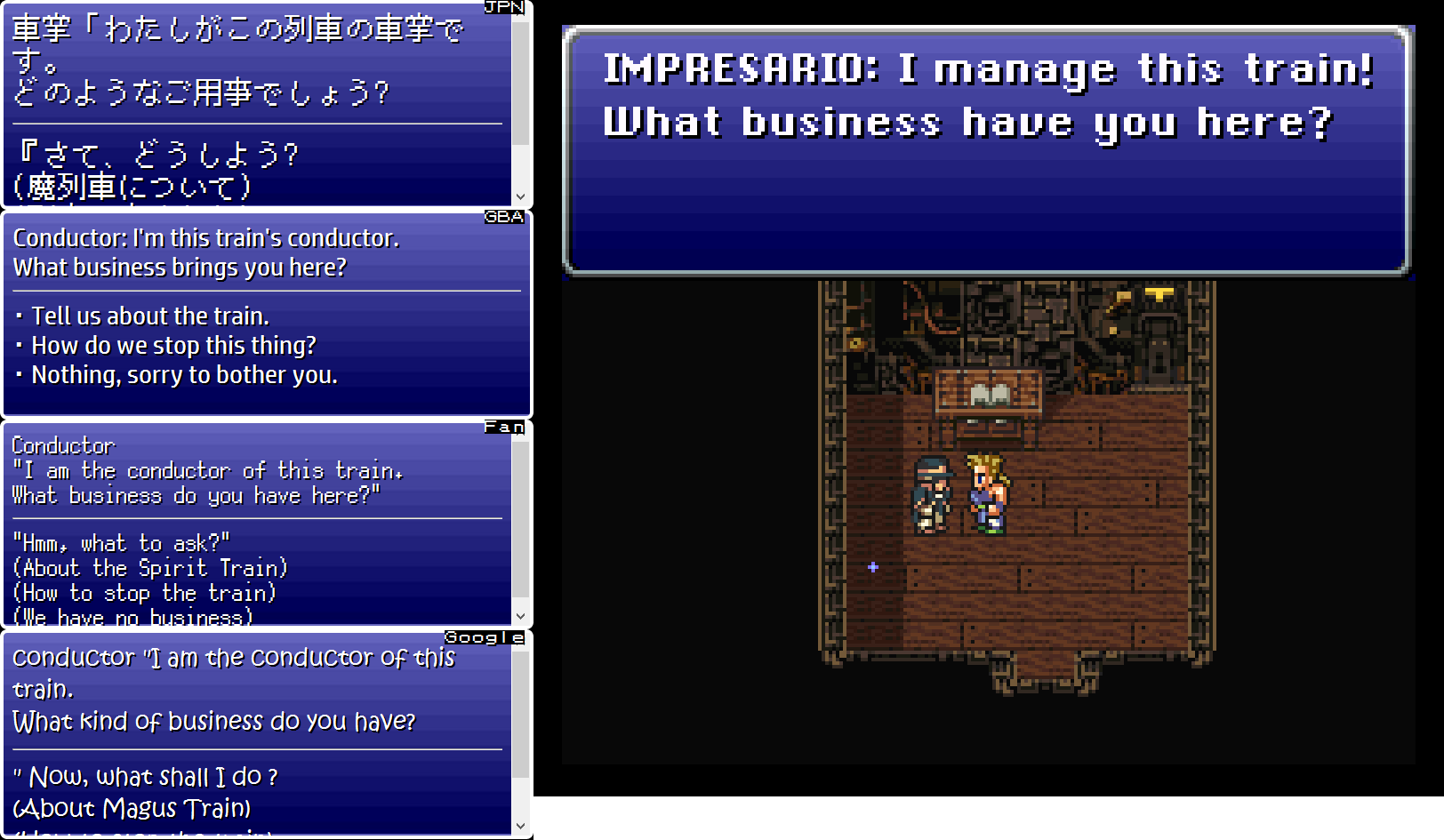

Two Conductors, Two Different Jobs

This guy in the back of the Phantom Train explains what the train is and how it works. I guess I never paid it much attention before, but he’s called the “Impresario” in the Super NES translation… which is kind of weird. I always thought the “Impresario” was the guy at the opera house later in the game. In fact, I think that’s the only time I’ve ever encountered the word “Impresario” in my life. So it’s surprising to see the name here too. What gives?

In the Japanese version, he’s labeled as “Conductor”, as in the kind that works on a bus or train. My theory is that the guy at the opera house was also translated as “Conductor” for a while, in the “music conductor” sense. But for some reason, the SNES translator decided to change the opera house “Conductor” to “Impresario” late in the translation process. He quickly went through his translated script and changed every instance of “Conductor” to the new name, but didn’t realize at the time that the word appeared in an unrelated part of the game too. And so now this Phantom Train guy has the same “Impresario” name.

As we can see, every other translation of the game gets this guy’s job title correct – even the machine translation.

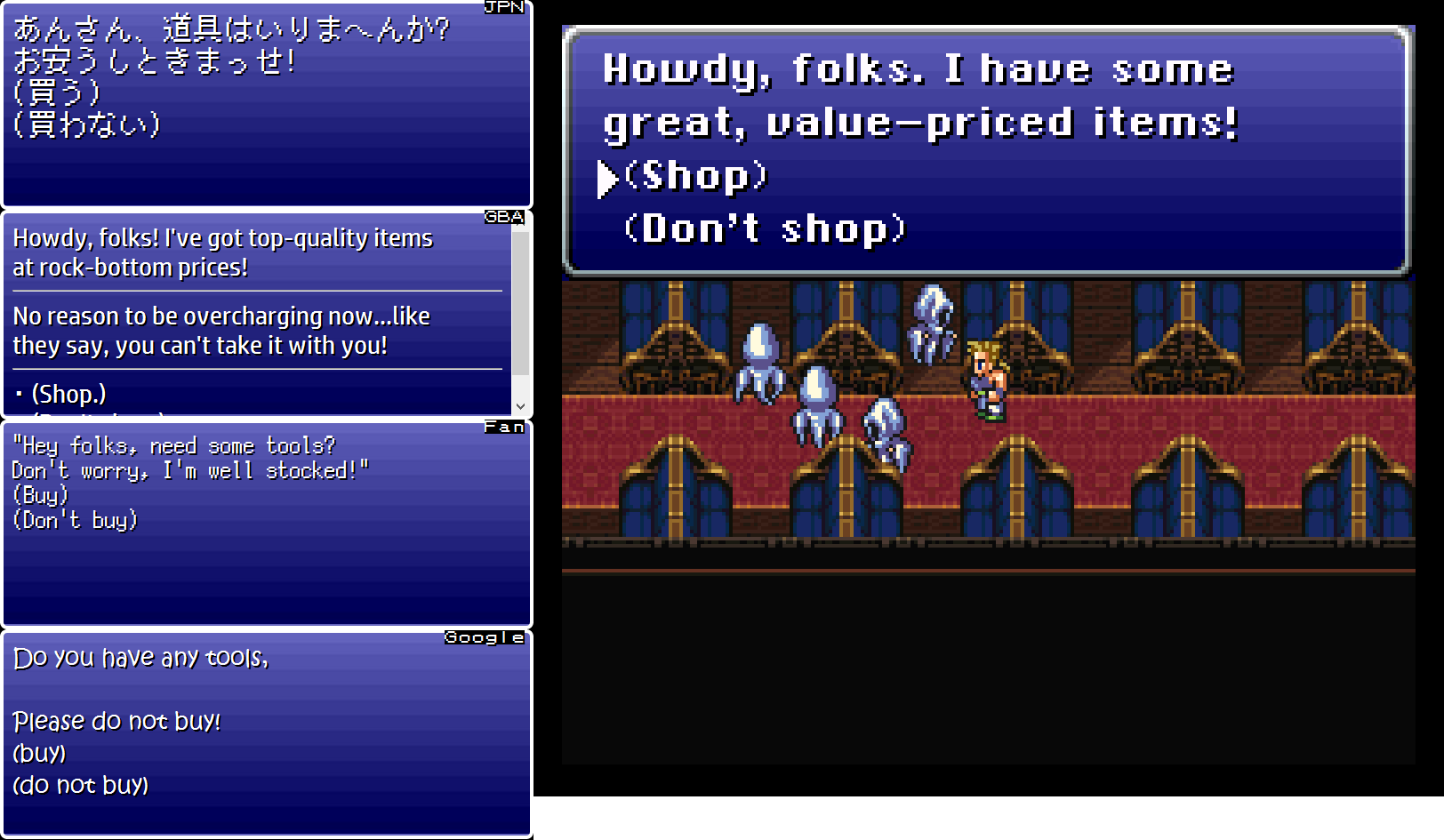

Tripping Over Dialects

Some of the ghosts on the Phantom Train act as ordinary shop merchants. In Japanese, these ghosts speak with a very heavy Osaka dialect. Merchants in Japanese entertainment often use this dialect – even the shop guy in the Zelda 1 uses it.

Setting this Japanese dialect aside, these ghosts literally say something like: “Hey, you there, need any items? I’ll sell them cheap for you!”

As we can see, none of the translations try to force an English dialect into the text. At the same time, the machine translation struggles to handle the ghosts’ dialect, which is understandable. The fan translation clearly struggles too.

Whenever a western Japanese dialect comes up like this, many translators immediately turn to accents/dialects from the American South – it’s almost like a cookie cutter, go-to translation choice. Here we see that the official translators looked past that easy choice and focused on the more important part of the ghosts’ speech pattern: that they’re merchants. We can see how the Super NES translation tries to convey the way a salesman might talk, but the GBA version does it much better – it sounds like something you’d hear on a stereotypical TV commercial for a local business or something.

Basically, this is all to say that: 1. dialects can be tough to translate if you’re not already at a high level of Japanese competency; and 2. dialects have multiple layers to them, and localizing a Japanese dialect into an English dialect is rarely straightforward.

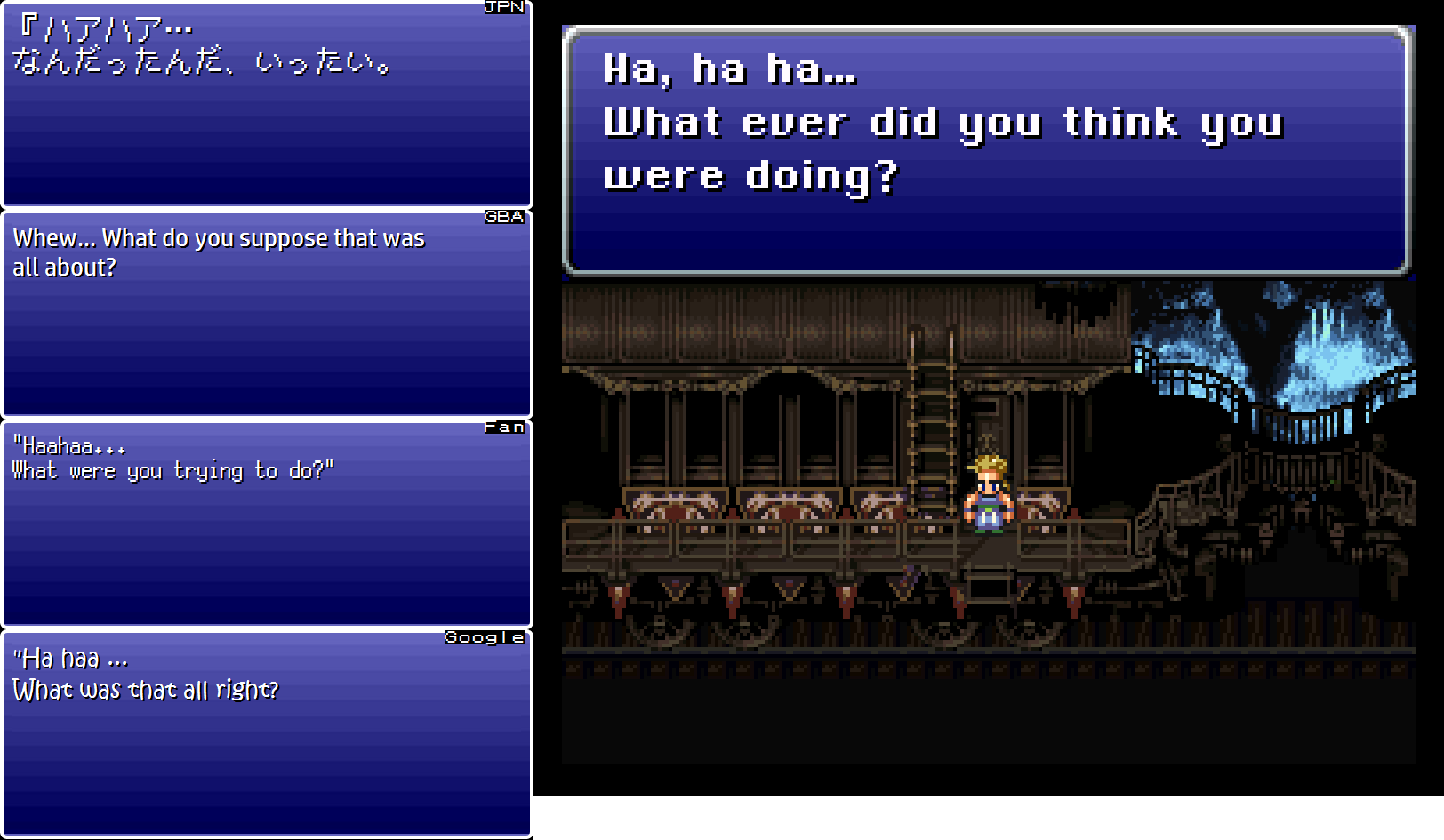

Stop Laughing

The party runs outside after some weird spooky stuff happens. A line of text appears, and in the Super NES translation it says: “Ha, ha ha… What ever did you think you were doing?”

There are multiple mistranslations here. First, it sounds like someone is laughing, but they’re not – they’re out of breath. This is exactly like the Kefka laughing/panting line we saw above. Someone mistook the “hā hā” gasping for breath sound for the English “ha ha” laughing sound.

Next, in Japanese, the second line is more like “What in the world was that about?” or “What the heck was that?”.

Given this, we can see that only the GBA translation gets this line right. The SNES translation, the fan translation, and the machine translation all fail in their own ways.

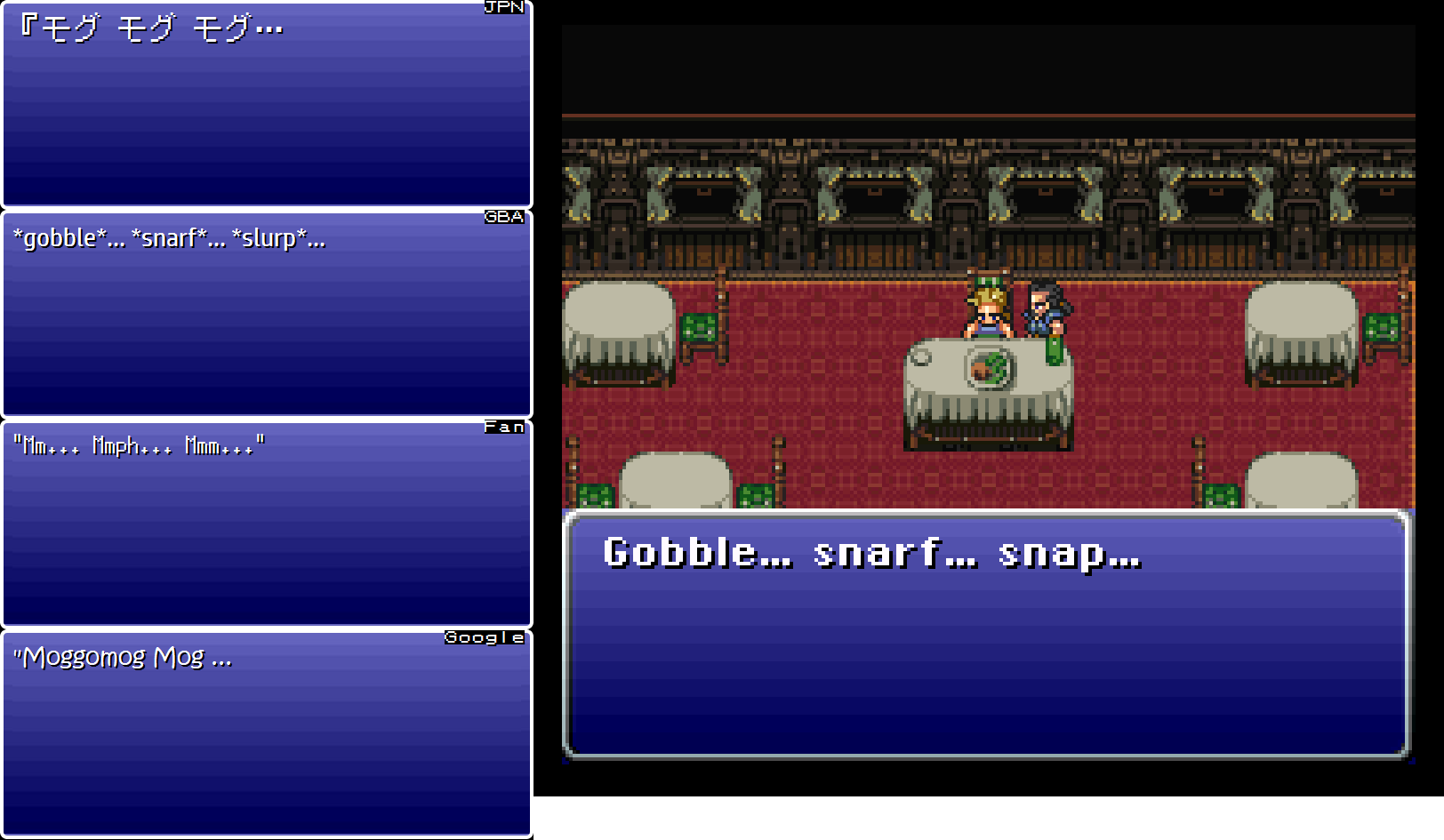

Ghost Dinner

There’s a special area of the train where you can eat ghost food. In Japanese, the food eating part is represented simply with something like, “Munch, munch, munch.”

To spice things up a bit, the Super NES translator used three sound effect words instead of one: “Gobble… snarf… snap…” This has become a memorable quote among fans.

The GBA translation leaves the iconic translation mostly the same, but changes the final sound effect word to “slurp”, which is more evocative of eating than “snap”.

The fan translation does something interesting, and the machine translation gets confused. Coincidentally, the eating sound effect word used in Japanese, モグ (mogu), is also how Mog’s name is spelled in Japanese, hence the Mog references in the machine version.

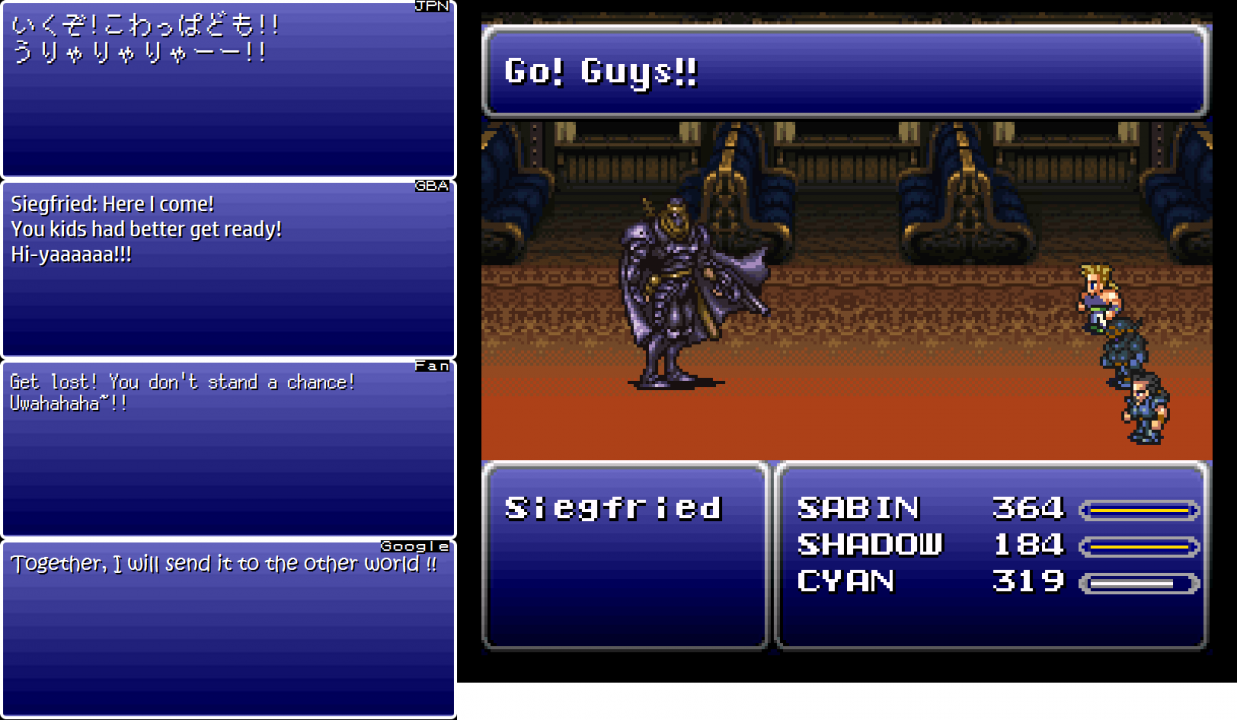

Ziegfried or Siegfried?

The party encounters a weird swordsman on the train. He’s first identified as “Ziegfried” in the Super NES translation, but then his name changes to “Siegfried” out of nowhere. Everything about this character and what he says always felt “off” when I played the game back in the 1990s, but I never quite knew why. It felt like something was missing.

The GBA translation fixes many of these problems and makes Siegfried sound more like he does in Japanese. The fan translation gets things wrong left and right, and I can’t help but wonder if my special program thing messed up the machine translation stuff here – it feels like it might’ve displayed the wrong lines here. I’ll need to double-check and see what’s up.

Anyway, I’m still not 100% sure what the deal is with this guy, but things make a little more sense in the Japanese version of the game at least. Maybe things will make more sense as we learn more about him in this playthrough.

The Baffling “Mr. Me”

After being defeated, Siegfried says in Japanese, “But the treasure is mine!”. He then takes the treasure and runs away. The fan translation handles the “I” in this line (and previously in this scene) in a very odd way, though. Here’s the quick explanation:

There’s a zillion different ways to say “I” or “me” in Japanese. There’s a rude, informal, masculine version of “I/me” in Japanese called ore. Tough guys, rude guys, and guys in close company tend to use ore. The Japanese language also has name suffixes: the most famous one is -san, but there’s also -sama. Putting -sama at the end of a person’s name is really polite and deferential – it’s basically putting that person on a pedestal.

So in Japanese entertainment, really rude/tough villains who also have a huge ego often combine ore and -sama to create a new pronoun: ore-sama. This pronoun is super common in anime, manga, games, movies, etc. For example, Wario uses ore-sama to refer to himself, and your rival in the early Pokémon games uses ore-sama too.

Normally, translators handle ore-sama by rephrasing things, like “I, the great Wario”. I guess the fan translators thought ore-sama was unique to Final Fantasy VI or that it’s a really important word that can’t be translated into English, because it’s translated as “Mr. Me” in the fan translation. I… never, ever imagined I’d see this basic term handled as “Mr. Me”. Every time I think about it I can only say “wow”.

They say that expert fencers, martial artists, etc. have the hardest trouble predicting what amateurs will do, because you never know what kind of random nonsense they might try. That’s exactly the same deal here – I never would’ve expected anyone to translate ore-sama this way. Indeed, even in translation, the amateur is formidably unpredictable!

I am impressed, though – it takes a lot of courage and conviction to stick to something that clearly sounds so strange in translation. If there’s one strong thread I continually feel throughout the fan translation, it’s passion.

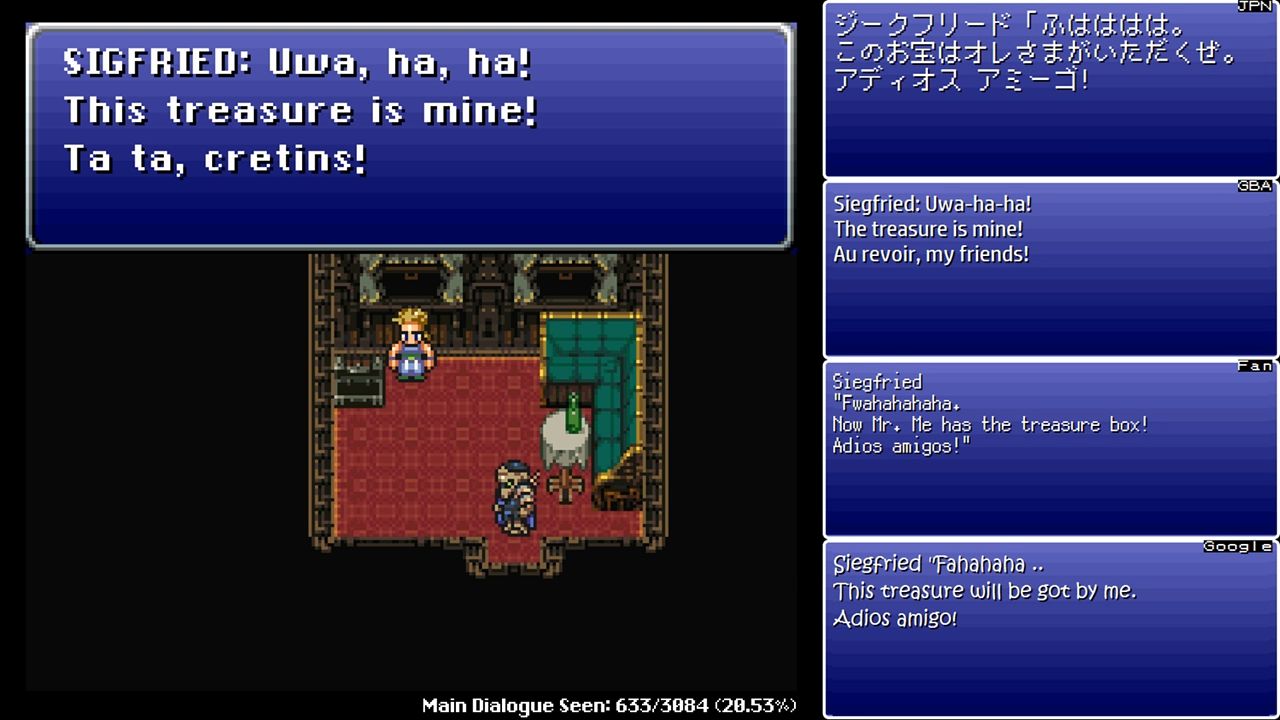

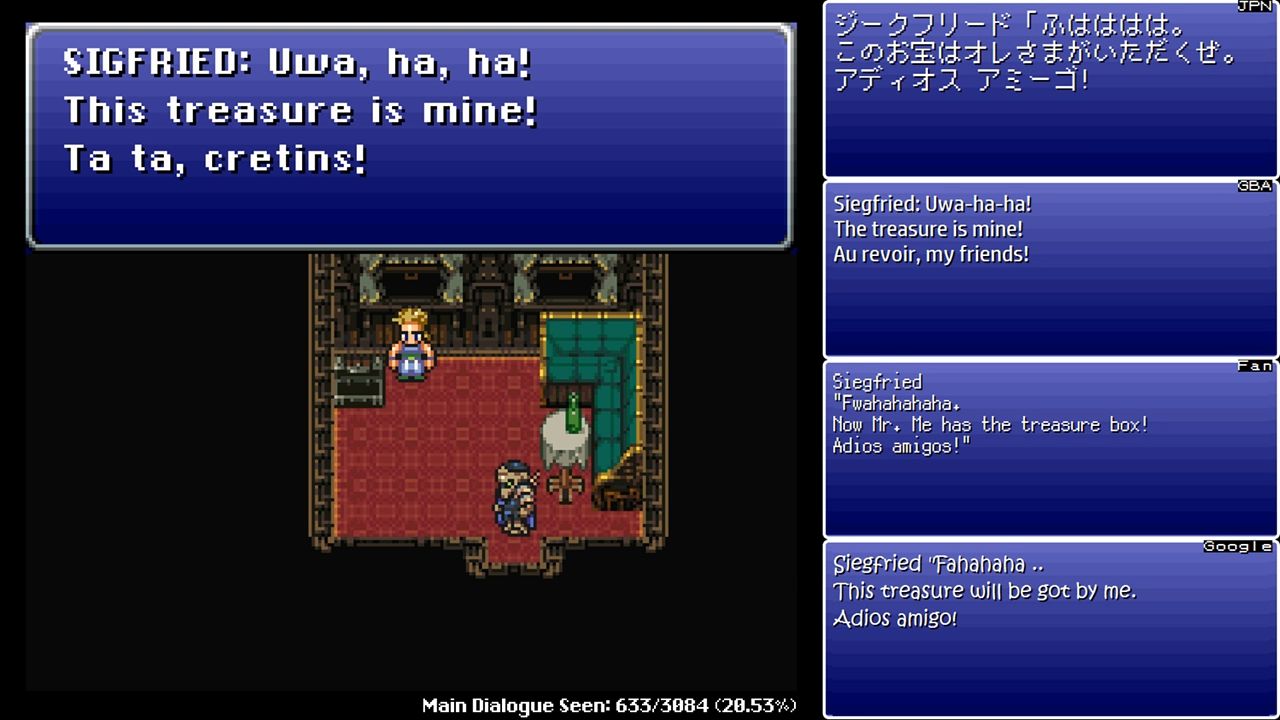

Hasta la Vista

Just before Siegfried exits, he says in Japanese, “Adios amigo!”. He literally says it in Spanish like that. It gives Siegfried even more of a lighthearted impression.

The Super NES translation changes this to “Ta ta, cretins!”, but the GBA translation changes it to “Au revoir, my friends!” to bring back the idea of mixing languages together to sound cheeky. The fan translation keeps the line in Spanish, and the machine translation keeps it in Spanish too.

Since Siegfried is talking to multiple people, I assume “adios amigos” is more grammatically correct, in which case the fan translation actually fixes the oversight in the original script.

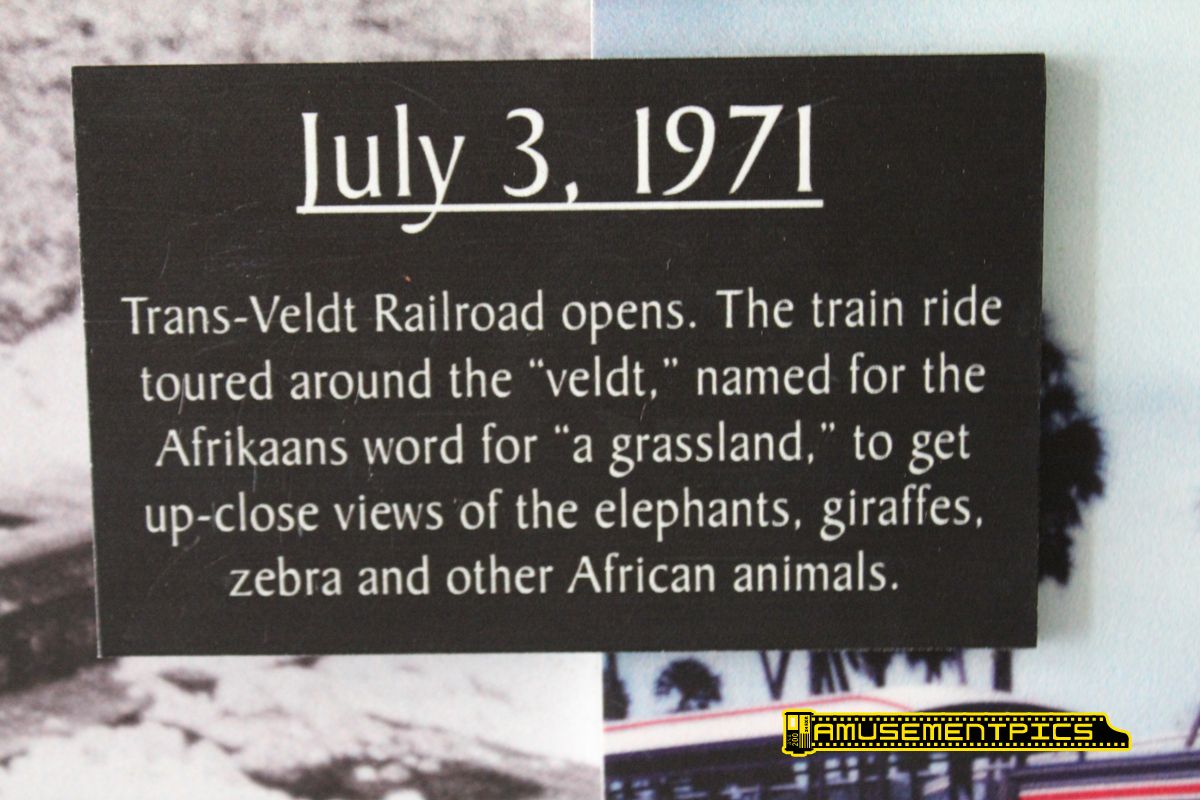

How the “Veldt” Got its Name

Sabin and Cyan head toward a place called 獣ヶ原 (kemonogahara), which translates as something like “Beast Plains”. This was renamed the “Veldt” in the Super NES translation and was retained in the GBA translation.

I always had an inkling that the word “veldt” had something to do with the plains in Africa, and a quick online search shows that to be the case. The word “veld/veldt” refers to the wide-open landscapes in southern Africa.

This “Veldt” thing is another case of a video game translation teaching a bunch of people about the real world. I actually prefer “Veldt” myself, as it sounds less on-the-nose than “Beast Plains” and thus sounds more memorable for me somehow.

(source)

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/bbenma.png)

I always thought Ziegfried/Sigfried was a little hint that the man you met was not the real thing. Later, at the Dragon’s Neck Colosseum, you encounter the real Siegfried who mentions a impostor who is implied to be Gogo. Ted likely intentionally misspelled his name to make it clear that he wasn’t the real deal.

Yeeah, the Siegfried stuff is thought to be a relic of a dropped sidequest involving chasing Gogo all around the world in various disguises before finally recruiting them.

It’s interesting that the machine translation in https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/ff6-day-04-014.png seems to handle ore-sama as a majestic plural. Shame it isn’t consistent about that elsewhere.

I agree about the Arthurian naming: at a guess, it goes with Cyan’s ‘thou’ tendency and the thought was something like: knightly, chivalrous… Arthurian.

Translating ore-sama was “Mr. Me” is so weird. I can sort of understand the logic of it (though it would make more sense if it was, e.g., ore-san rather than -sama), but it doesn’t convey the actual connotation of Japanese at all.

The subtitles for “Netoge no Yome wa Onnanoko ja Nai to Omotta?” translated ore-sama as “my bad self”, which I found hilarious (and fitting the context of the show better than it would most of the places ore-sama is used), so I’m always reminded of that anytime I see ore-sama.

If I’m not mistaken, for the JoJo’s Bizarre Adventures OVAs from the nineties, the phrase “kono Dio-sama” was translated as “I, Dio”. I think this is a pretty good equivalent, in that it’s something no one says in real life, but still doesn’t sound awkward.

Translating “kono (name)” as “I, (name)” is such a super standard translation I don’t think I’ve EVER seen it translated differently other than the lazy cop-out of just going with “I”.

I think I can kind of see what Sky Render must have been thinking when he translated 「オレ様」 as “Mr. Me”: even though what it’s supposed to convey is Siegfried talking up what a great swordsman he thinks he is in an over-the-top arrogant way, it’s like there’s a kind of redundancy there. Using 「オレ」 as a first-person pronoun, and phrasing “it’s mine” along the lines of 「オレの物だ」, would be common enough to be completely unremarkable (in entertainment, at least, not so much in real life.) But instead of the simple 「オレ」, Squaresoft had him use 「オレ様」, which could be literally translated as something along the lines of “My Highness” or “Lord Me”. It’s like he’s giving himself an additional title beyond what would normally be considered correct usage.

And while “Mr. Me” doesn’t have the same grandiosity as a character who refers to himself as “Lord Me”, it has a sort of catchiness and alliterative appeal that seems appropriate for a character concept that’s as silly as Siegfried is. He appears out of nowhere, taunts you about how much stronger and more famous than you he supposedly is (even though nobody but the equally crazed Ultros ever gives any indication of having heard of him and the fight with him is basically impossible to lose,) and then he just runs away and disappears with no more explanation than was given for his entrance. Honestly, I’m not even sure “Mr. Me” makes any less sense than a lot of things that have been tried in translations to convey speech patterns that don’t have a real equivalent in English, even in commercial productions, like when the English dub of Rurouni Kenshin translated every instance of 「でござる」 as “that it is”.

The real issue I have with “Mr. Me” is that I will never be able to hear it and not immediately think of this song.

(And I’d actually argue that’s an example of a legitimate issue that can come up in a localization: sometimes, even if a prospective translation of a line seems to convey the correct meaning, it can turn out that that specific choice of words has cultural connotations, or sounds like a reference to another work, that doesn’t fit with the tone you’re trying to set. One example that seems to be pretty common in Japanese-to-English translations is translating a statement like 「僕と遊ぼう」 as something like “come play with me”: in English, it’s a lot easier for that to be interpreted as having sexual connotations than it is in Japanese.)

The reason I’m astounded by “Mr. Me” is because I’ve never heard the phrase before watching the livestream, and it doesn’t seem that anyone else here has.

Also, I’ve heard from several people that “ore” is actually a very common casual pronoun among males – to the point that NOT using it at least occasionally among friends might get you funny looks.

Yep, it’s a super, super common pronoun – so much so that it feels weird having to describe it sometimes. I’m slowly putting together a big article about Japanese first-person pronouns, so that’ll give me a chance to explain it in better detail.

My personal favourite is the various translations of Guzma’s ‘ore-sama’ and ‘Guzma-sama’ lines in Pokemon Sun/Moon; in the English he says stuff like ‘ya boy Guzma’ and ‘big bad Guzma’, which has the same arrogant feel while also fitting with the whole gangster/rapper aesthetic he has going on.

I think it makes a lot of sense where he was coming from. It’s obviously not the best translation, but it does fit the connotations implied by ore-sama and his goofy characterization. The insistence on “mister” actually fits the kind of English speech pattern where a kid or something calls an adult by a more familiar term or name, and the adult replies “That’s “*Mister* [whatever]”.” You gotta read it with the emphasis on “me”. English speakers might also refer to themselves in the third person with “Mr.” (or without) to claim possession of something: “Now Mr. Siegfried has the treasure”.

I admire the creativity here, even if a more experienced translator might have picked a more obvious option.

“Howdy” does give a bit of a “southern” flare to the ghost merchant, but on its own it doesn’t really indicate southern on its own. “Howdy partner” or “Howdy there partner” over “Howdy folks” would convey it more, even if it’s more “cowboy” than “southern”.

Or maybe “Howdy ya’ll”.

I dunno, I feel like the deliberate choice of “howdy” was intended to create a dialect. It’s more pronounced in the GBA version where he quotes some folksy wisdom. I feel like the official translations did a good job of conveying a different feel to the dialogue without beating you over the head with it. I mean, that ghost is memorable BECAUSE he talks differently (not poorly, but with a, well, dialect).

“It’d be like if you asked a Japanese kid who’s just started studying English to translate Shakespeare quotes.”

Recalling my grade and high school days, it’d also be like asking a native speaker to translate Shakespeare quotes.

“for every sentence in Japanese there should be exactly one equivalent sentence in English too”

This was hotly debated in early fan translations, where “purists” would argue that even sentence structure should remain intact, even though structure, syntax, and assumed context are completely different between Japanese and most other languages.

Forget Japanese-to-English. Even translating word-for-word between closely related language (such as, say, German-to-English) results in borderline gibberish.

I sometimes find it weird that English syntax has more in common with French than German, despite being a Germanic language.

You can thank William the Conqueror for that. He brought a Norman dialect to a defeated England in 1066, and it stuck permanently, at least in creole form.

The idea that English is a creole is a persistent misconception among people who have only a vague idea of what a creole is.

“Purists” don’t exactly have any common sense nor any understanding of the Japanese language.

If I recall correctly, a more recent game, Pokemon Sun and Moon, had a villain use ore-sama and it was translated as “ya boy”, which people said was great because it got the tone of being not only pompous but also overly familiar. Least that’s what I’ve heard he said in the original. I just remember that’s what people said about the translation.

Later on in the second part of FFVI you meet Sigfried and he tells you someone has been impersonating him. I think that’s why the first translation spelled the name in the train different, to establish that these are different people.

As a Spanish speaker, there’s actually a slight mistake with “Adiós amigos”: there should be a coma after “adiós”. There’s also the issue of the missing exclamation sign at the beginning and the missing accent, but I understand one wouldn’t create new characters just to use them one time.

Fascinating as always to see how the various translators/localisers handle the lines of characters with unique or distinct speech patterns. Cyan in particular speaks, as you mention, in a Samurai-esque manner with equates to a chivalric, Shakespearean tone in English. I am curious as to how many of these translations kept “thou,” which reflects Cyan’s おぬし

/お主 (onushi; itself an archaic pronoun used by samurai and ninja in fiction as an informal one of sorts, equating to お前 [omae] in Modern Japanese.) Obviously the original SNES translation by Woolsey keeps “thou,” but the Shakespearean grammar is far from perfect in that version, much in the same manner of Frog’s in Chrono Trigger.

A point of interest is that his mode of self-reference changes ever so slightly in the Japanese version, where he will on occasion in grandiose fashion use 我 (ware) when threatening an enemy, otherwise it’s mostly 拙者/せっしゃ (sessha) the default (humble) pronoun of samurai and ninja, literally meaning “this clumsy/crude fellow.”

Back in the day, the Wheel of Time series of fantasy novels were popular at around the same time as Final Fantasy VI (or, to us, III), and a lot of people noted that Cyan’s family had names that were similar to characters from that series named Elayne and Gawyn (who themselves were Arthurian references).

I think a lot of people, myself included, suspected that “Owain” was an alternate spelling of “Gawain,” but the two names seem to be unrelated in Arthurian legend based on Googling today.

I almost wonder if the Veldt rename was a result of Ted having been an avid sci-fi reader or something; there’s a famous Ray Bradbury story by that name, where a family owns a virtual reality room (a Holodeck in all but name), but their kids keep setting it to bring them to the Serengeti, to which they warn several times that that’s dangerous because of the wildlife. Considering the mechanics of the in game Veldt, to where any previously encountered enemy can appear randomly…Yeah maybe it’s a bit of a stretch, but considering I’ve seen weirder (all the Tolkien references in Symphony of the Night)…

I was actually going to post this same thing, I’d consider it likely it’s also referencing the short story (I’d assume the short is named after the ‘real’ Veldt). Since you can encounter anything there, and the Veldt in the short also allows you to see pretty much anything

A Tumblr user named kaialone used to do comparisons between the Japanese and American English scripts of The Legend of Zelda: Spirit Tracks, and she pointed out that Byrne/Staven calls himself “ore-sama”. She also pointed out that there’s a joke in the Japanese version of the cutscene after the boss battle with him where Zelda almost forgets to put an honorific after his name.

On a whim, I googled “ore-sama” and “Mr. Me” and discovered that linguistics book proposed “Mr. Me” as a jocular translation back in 1999: https://books.google.de/books?id=TEjtxpTnJYcC&q=“ore-sama”+”Mr.+Me”

Haha, wow, nice find!

And holy moly, right below it is mentions of “-tyan”, yikes. That’s the bizarro way of writing “-chan” – I wonder if anyone ever learned it this “-tyan” way and tried to say it that way in Japan.

About the Ziegfried/Siegfried/Sigfried naming in the SNES-translation… there’s an extremely subtle inconsistency with his name in the Japanese script. In the Japanese version, all character names use halfwidth characters.

ジークフリード instead of ジークフリード

The ド in his name is fullwidth on the train but is halfwidth when you later meet him in the World of Ruin. This was probably just an oversight, but could it perhaps be the reason why he ended up with different names in the SNES-translation?

Final Fantasy XIV makes heavy use of Doma in its most recent expansion, Stormblood. Said expansion’s story is basically focused around the good guys working to liberate both Doma in the far east and the nearby country of Ala Mhigo from the Garlean Empire rule they’ve both suffered under for the last 20 or so years.

One of the major characters who you team up with in the Doma side is Prince Hien, who turns out to be XIV’s version of Shun, complete with in-game references to his mother Mina, and complaints from him asking his retainer to quit using his birth name. (an arrangement of Cyan’s Theme from VI plays in XIV when you first meet Hien, and it legit sent chills down my spine)

Anyway, all this is to note that Hien’s father had his name written in English in this game as Kaien. I guess in these days of gamers being more familiar with Japanese names and terminology that the localization team was fine with going that route as opposed to the old-school Cayenne/Cyan mentality.

Wait so… Dumb question… is Cayenne pronounced like the spice?

Yeah, more or less.

the “Ore-sama” thing is one thing I’ve been interested in tackling myself. I’m thinking Siegfried frequently referring to himself as “The inimitable/invincible/magniloquent Siegfried” woudl work since he’d try to use big words to sound like a big man, yeah? How’s that sound?

Bit late, but the official soundtrack for the game translates 獣ヶ原 as “Wild West”, which seems to be the “official” English name for it in Japan.

It’s… creative, especially considering the place is located in the southeast.

I’m Mr. Me, look at me!

Go to Google Translate. Type in “sama” by itself. It will return “Mr” in English.

Delete “sama,” and type in “ore.” GT will return “Me.” Et voilà!

The mysterious “Mr. Me” is solved!

It was never a mystery.

Well, it was never explained in the thread: so (if you like) the unexplained non-mystery is now an explained non-mystery.

Anyway, I was proud of myself for discovering that, why you have to shoot me down?

The way in which you said it came across as condescending.

I think the simplest translation of ore-sama is bad-ass motherfucker: It keeps the narcissism,implicit evil and even the punctuation.

I didn’t think much of it at the time, but after gaining some understanding of Arthurian legends, I’m certain that Owain and Elayne are references to them, especially considering Cyan’s reflavoring as an old English knight and the fact that like 90% of all Arthurian female characters are named “Elayne/Elaine”.

I read that the name of “Cyan/Cayenne” is based on “Kaien”, an old Japanese name fitting for a samurai. I don’t know how much truth there is to that, though. Either way, if I were to (re)translate the game, I’d probably change his default name to “Kaien”. It gets the pronouncation across, sounds suitable exotic (assuming Doma would retain its “Japanese flavoring”) and avoids peppering the game with names that could look silly.

The concept of translating/localizing regional dialects is always weird to me. Like, it’s not like you can just 1:1 swap a dialect of a certain part of one country with a part of another, the cultural differences make this a fool’s errand. I could never see myself doing something like that, trying to translate a non-German dialect into a German one. At least, not without it sounding jarring, completely unfitting and utterly stupid. I think such things should just be dropped as a casualty of localization.

I really wonder why the GBA version has Siegfried saying “au revoir”. I mean, “adios amigos” sounds fittingly casual, while “au revoir” sounds a bit too fancy (as French tends to do).

Back in the day, “Ziegfried” always looked strangely German to me, since “Ziege” means “goat” and he really looks a bit like a goat in his sprite. Or some other kind of animal. As much as I like the FFVI character sprites, they can really look strange and awkward at times. But I can’t complain too much, since that led to the Gestahl puppy minion in FFXIV.

The GBA translators are absolutely putting a dialect/regionalisms into the ghost shopkeepers’ speech – it’s just not a generically Southern one.

It’s Texan.

I suspect the GBA translator has read TV Tropes, which specifically uses the Texan example to explain the combinations of connotations of the Osaka accent. Commercialism (Texas oilman), directness and informality, regional pride, &c

Right. I’d say “Howdy” there is the usual attempt to turn Osakan dialect into some version of Southern/”hick” U.S. English dialect—in this case, the pop-culture concept of Texas-talk that anyone from anywhere else in the U.S. would pick up from sitcoms or kids’ television. It’s just an attempt that’s particularly… well, if I wanted to be generous, I’d call it “efficient”, and if I didn’t, I’d call it “lazy”. It’s not any worse, though, than the intrusive and distracting attempts we get sometimes, where characters who talk in various Japanese dialects have their lines localized in ways that make you expect them to order a sarsparill-y at the ol’ watering hole before they ride a mustang bareback off into the sunset.

I think it’s just as interesting, given the topic of this site, that our inestimable M.C. here didn’t register “howdy” as suggesting a dialect at all! I suspect he’s not alone, though. I myself have seen “howdy” transition in certain professional circles from an ironic greeting delivered in a flat, “up North” accent, to draw attention to the incongruity of deploying what a lot of people in the U.S. see as broadly comic movie-cowboy-speak, to just another way of saying, “Hi.” Maybe that’s where it’s headed.