This is part of my ongoing series in which I compare four translations of Final Fantasy VI with the original Japanese script. For project details and my translation notes from Day 1, see here.

Part 12: World of Ruin #1

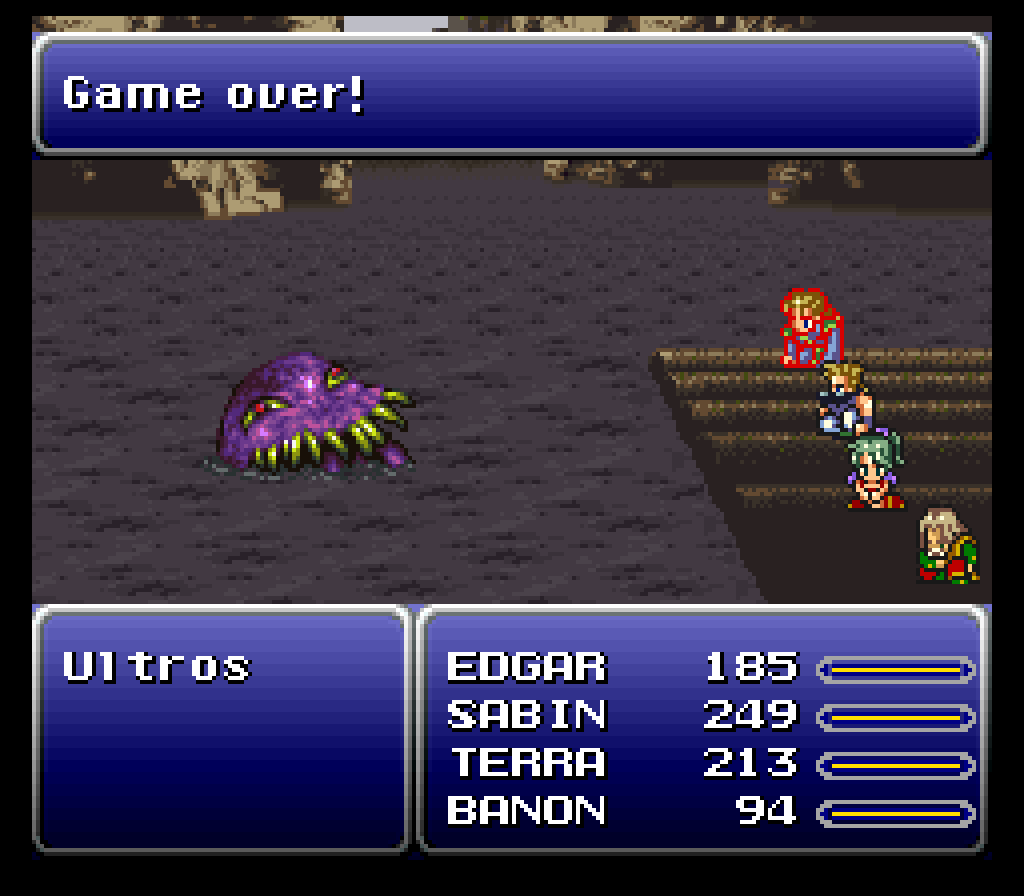

After some initial setup, the game opens up and lets the player freely explore the world. This makes it hard to specify where each article starts and ends now, but I’ll try to do my best to keep things organized. For this article, we’ll be starting from the beginning of the World of Ruin and ending shortly after getting the airship and finding Cyan.

Video Archive

This article covers content from two and a half live streams. You can see the archived videos here:

- World of Ruin begins

- Finding Sabin all the way to finding Edgar

- Finding Setzer all the way to finding Cyan & Gau

Notes

My notes below are just a fraction of all the translation topics I covered during this stream. So if you want to see more changes, mistakes, and such, check out the first half of the video above.

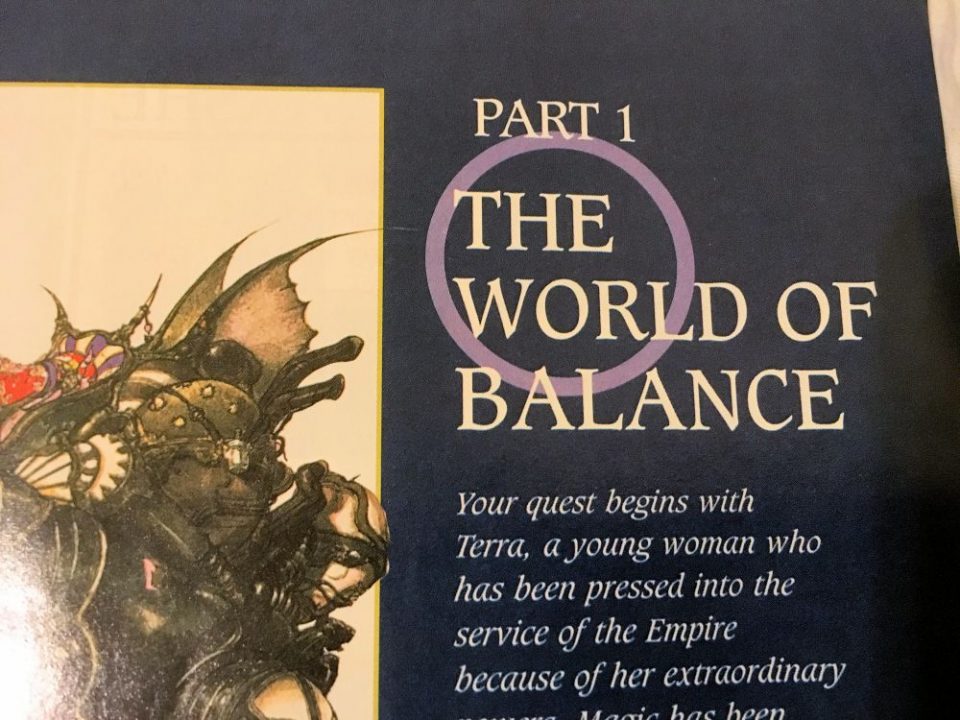

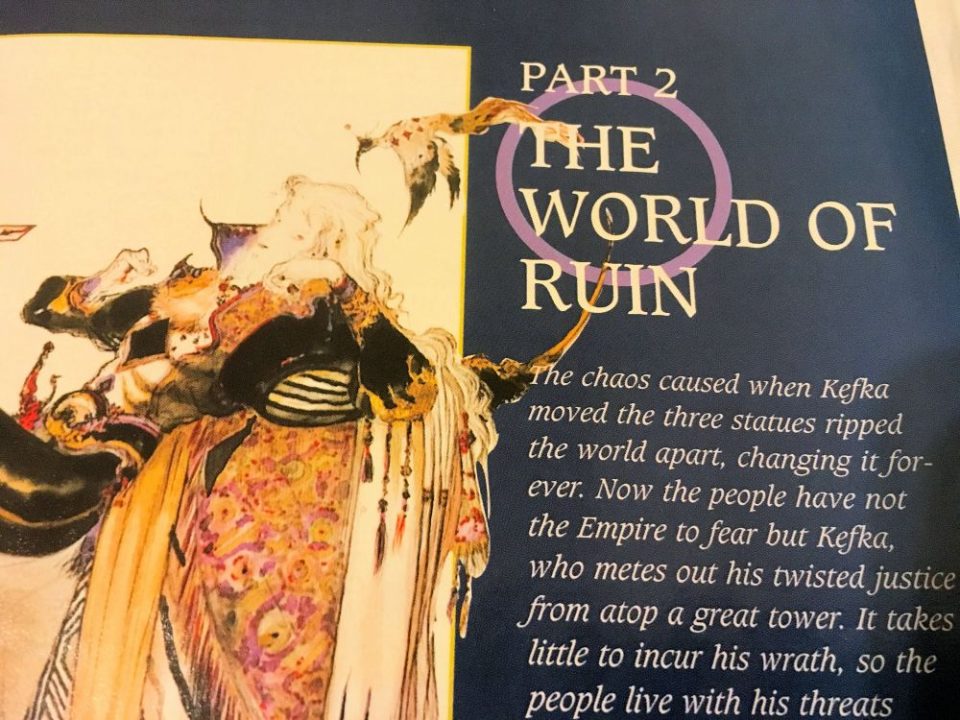

World Names

English-speaking fans of Final Fantasy VI use the terms “World of Balance” and “World of Ruin” to refer to the two different parts of the game. I don’t know where I picked up the terms, but even I remember using these names back when the game was released.

Whenever this happens, my first instinct is to check the popular magazines from the time. And indeed, it seems the official English strategy guide used those specific terms with strength:

I never owned the official guide until now, so I can only assume I encountered the name via an issue of the Nintendo Power magazine. I’m curious, though – do you remember how you first came to know the “World of Balance” and “World of Ruin” terms? Let me know in the comments!

Anyway, a reader was curious about what terms are used in Japanese. I checked my big stack of official Japanese guides and materials and there doesn’t seem to be a specific term for either thing. At most, they’re referred to as something like “pre-destruction world” and “post-destruction world”, but even then there are variations on how those phrases are written in Japanese. In short, there don’t seem to be specific terms for these two worlds in Japanese, at least not in the same way that there are specific terms for them in English.

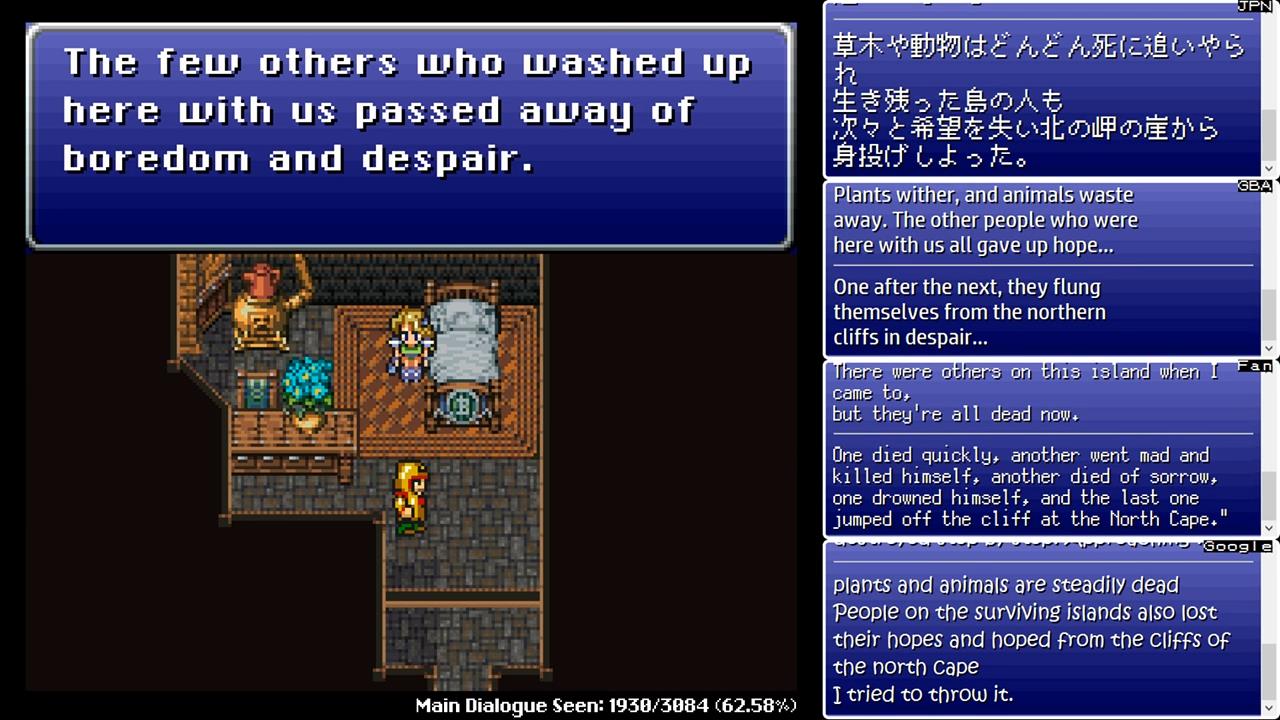

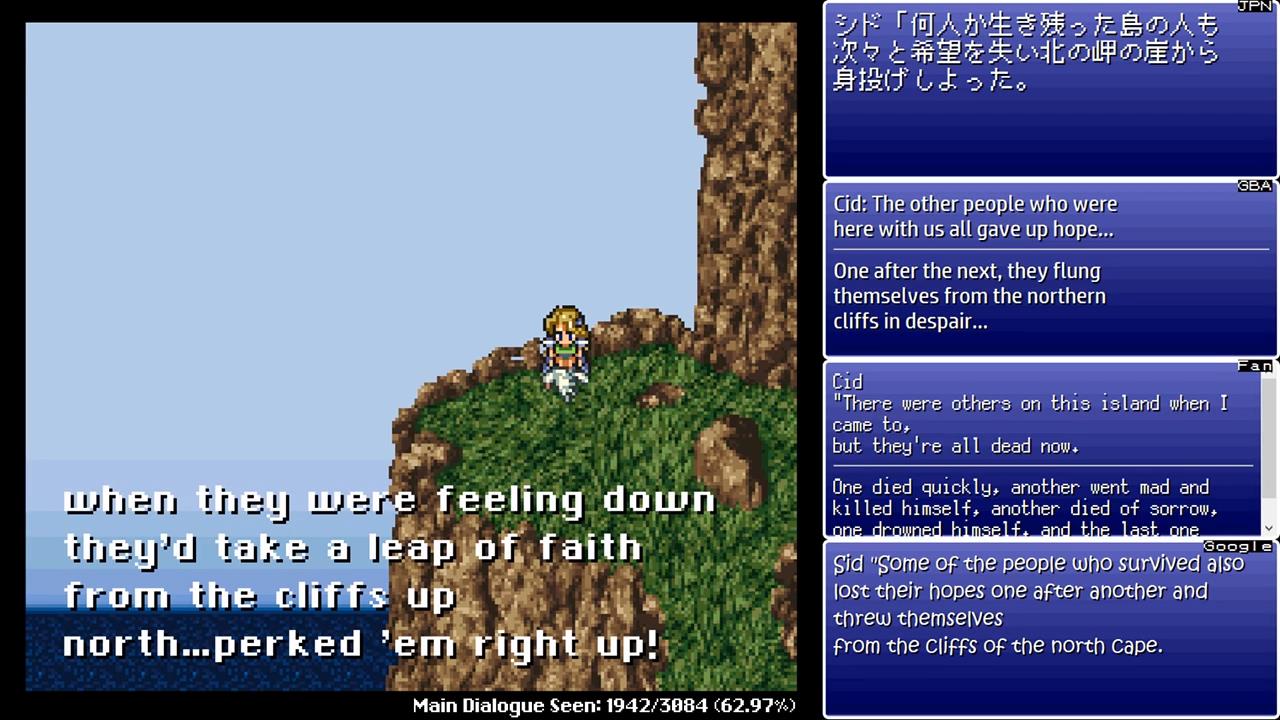

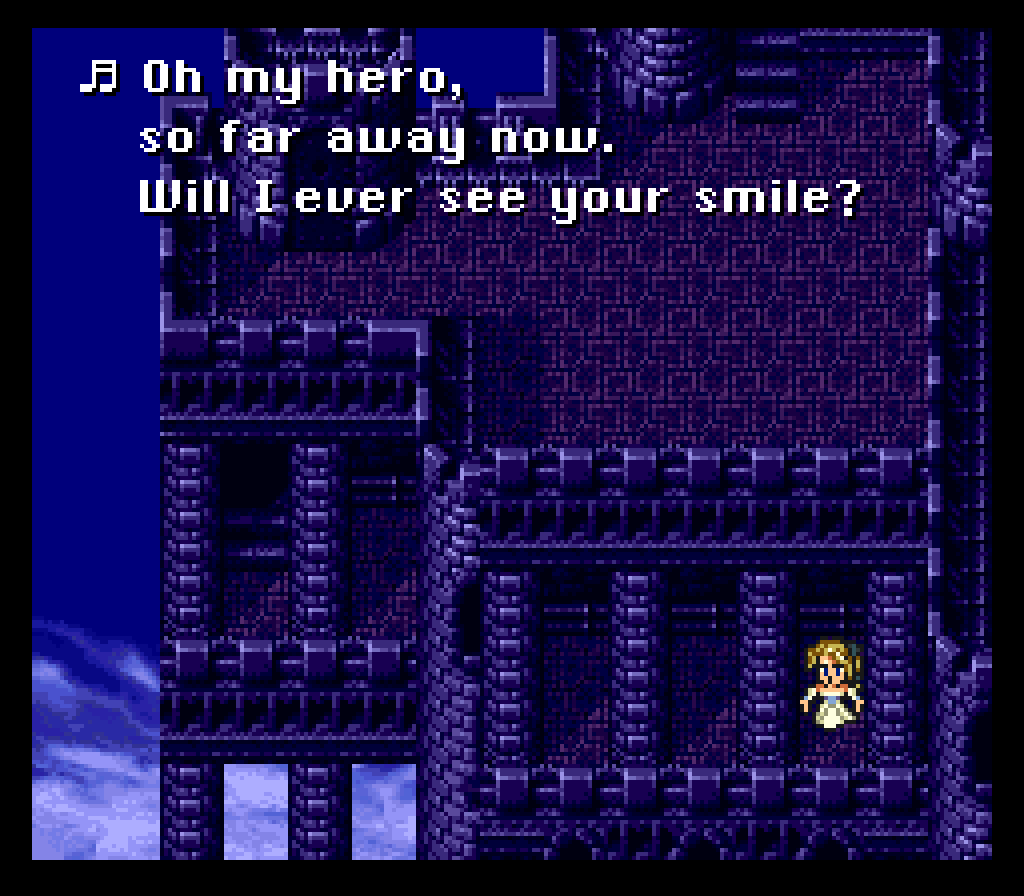

Celes on the Cliff

One of the biggest and most famous changes in Final Fantasy VI’s Super NES localization happens here. Basically, the world has been torn apart and Celes and Cid have been on a deserted island for about a year.

Once you take control of Celes, you’re able to nurse Cid back to health or let him suffer and die. If Cid dies, then Celes is filled with sorrow and runs to a cliff on the north side of the island. In the Japanese version, she jumps off the cliff to commit suicide. In the Super NES version, text has been changed and moved around to indicate that jumping off the northern cliff is a good way to cheer up when you’re feeling down. This change was done to comply with Nintendo of America’s content policies about death and depictions of death.

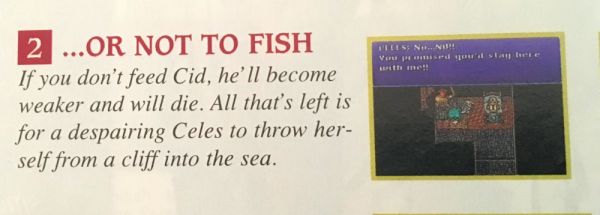

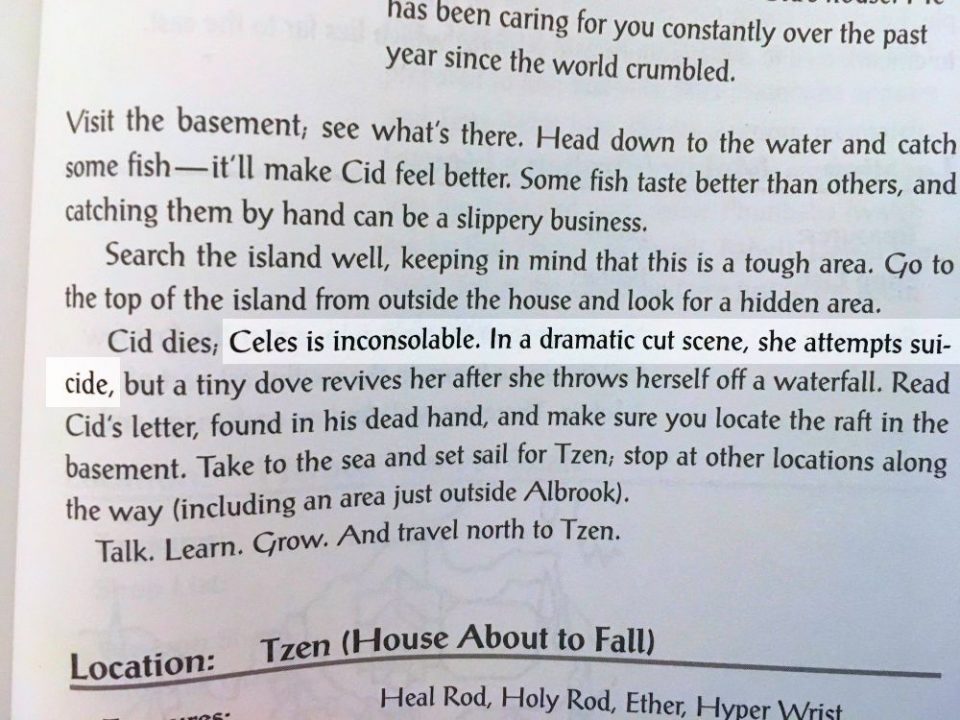

Editing or removing the entire scene would’ve required a lot of technical work, so the simpler alternative was to leave the scene in but change all the surrounding text to change the reason for Celes’ jump. Despite these changes, I seem to recall that fellow Super NES players could still tell that something wasn’t right. Some of the old FAQs from back in the day saw right through it and talked about her trying to kill herself. Even the official Nintendo Power guide phrases it in a way that suggests Celes was doing more than trying to “perk up”:

Meanwhile, one of the unofficial strategy guides just comes right out and says it:

All this is to say that despite Nintendo of America’s content policies, the changes to the scene were hardly convincing.

These changes were dropped in the Game Boy Advance translation a decade later. The fan translation sticks close to the original text, but it does make a number of translation mistakes while doing so. For all the details about specific lines, see the video archive listed above.

Improving Cid

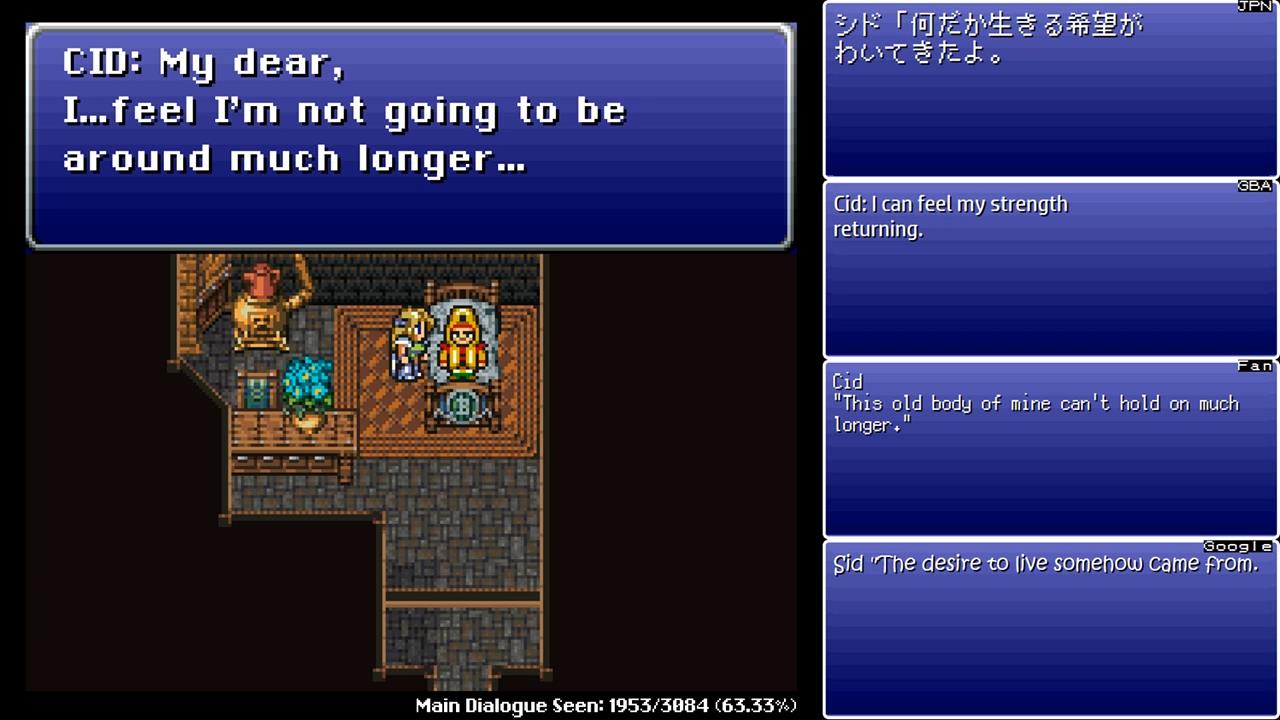

If you work hard to keep Cid alive, he’ll eventually say in Japanese:

I’m somehow filled with the hope to live.

The Super NES version of the same line says something very different:

My dear, I… feel I’m not going to be around much longer…

That’s the exact opposite of what he’s supposed to say! And we can see that the fan translation is simply a rephrasing of the incorrect Super NES line. The Game Boy Advance version of this line doesn’t mention hope, but it at least gives the player the correct impression that Cid’s health has improved.

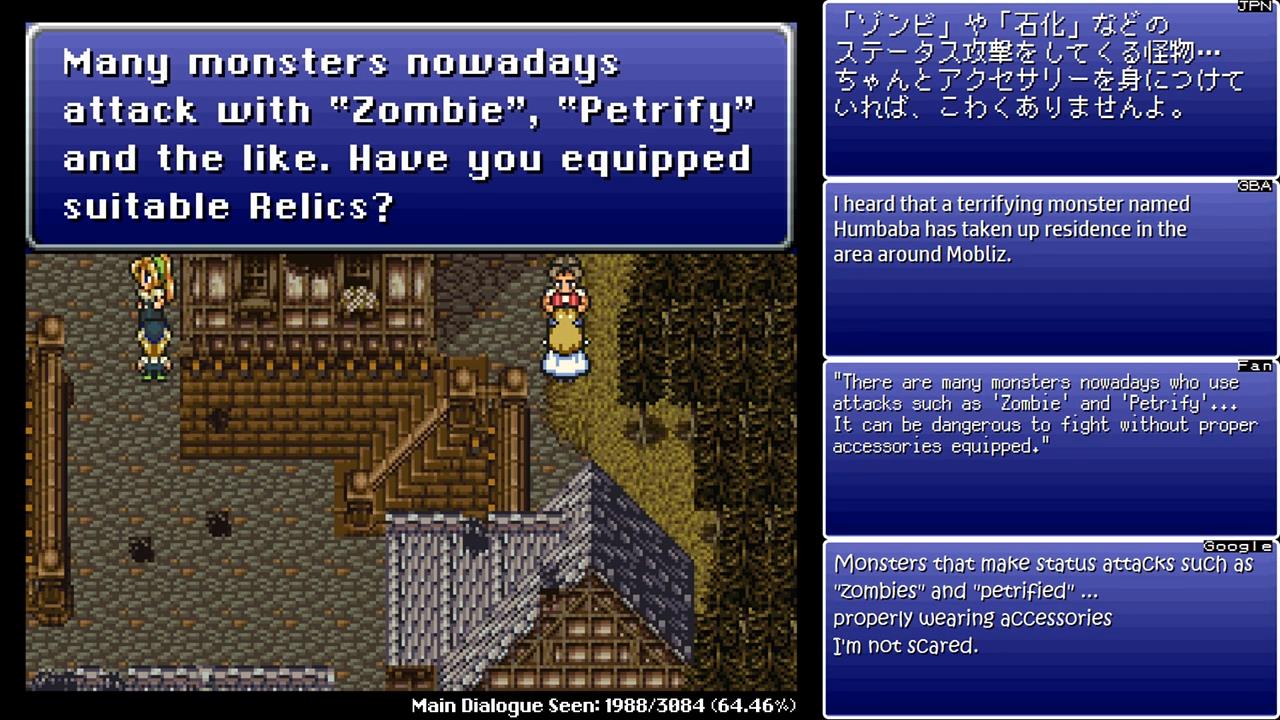

Facts or Advice

In the Japanese Super Famicom version, this character gives you advice about using relics to avoid dangerous status ailments that enemies can inflict. The Super NES translation and the fan translation also give this same advice. The Game Boy Advance version of this line has been completely changed though – instead of giving advice about equipment, he mentions recent events in a different town.

Out of curiosity, I checked the Japanese GBA version of the game and it too has been changed in the same way as the English line.

|  |

| Japanese GBA script now talks about Mobliz | English GBA script also changed to talk about Mobliz |

I wonder how many other lines from the original Japanese release were changed like this for the GBA release. If you know Japanese and are also interested, I found a list of Japanese text changes here, but it doesn’t appear to be comprehensive.

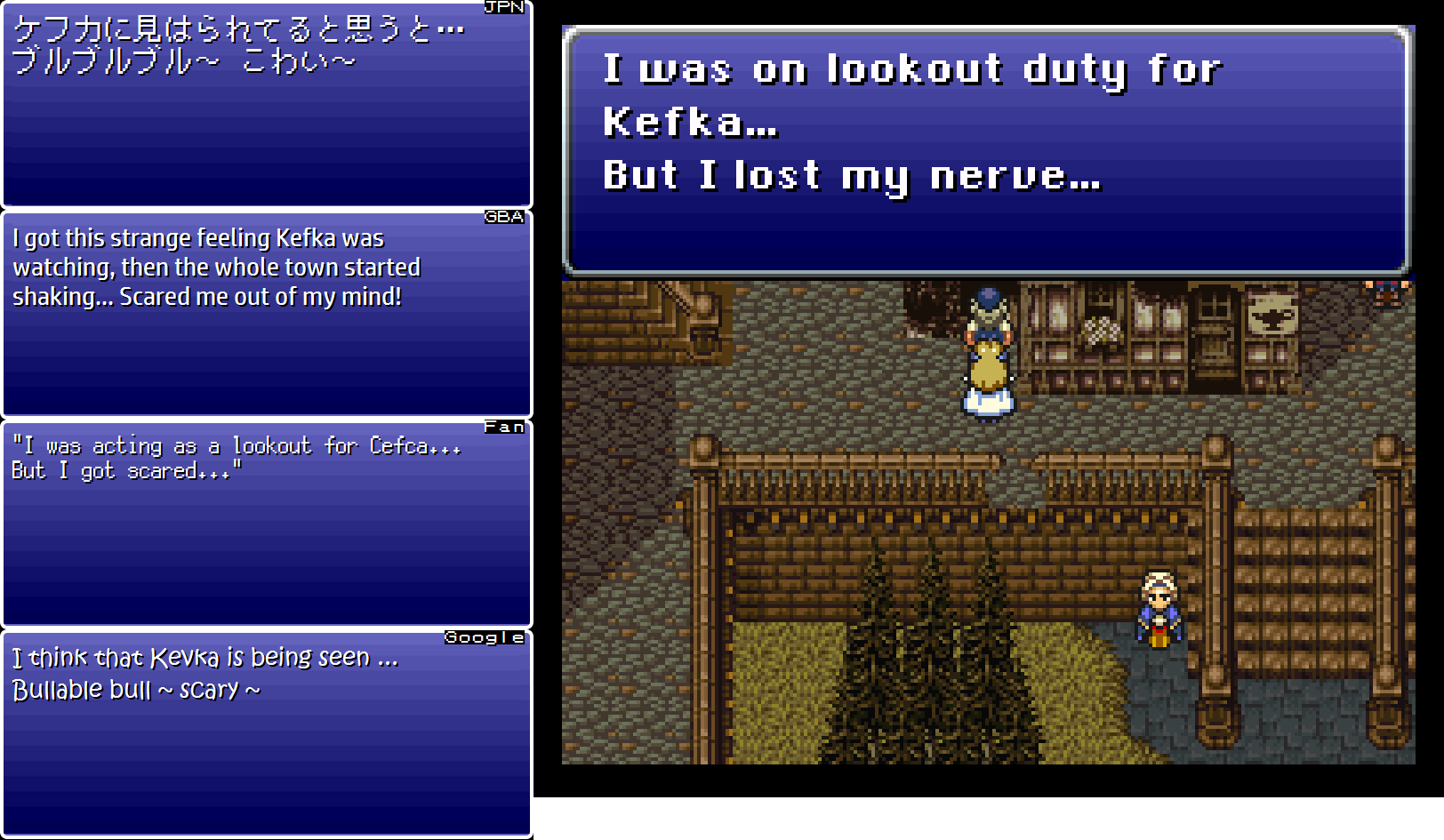

Kefka’s Lookout

This man in Tzen says in Japanese:

Whenever I think about Kefka keeping watch over us… *shiver* Talk about scary!

The Super NES translation gets this line exceptionally wrong. You can kind of see how the mistake came about, though: Kefka is mentioned, the idea of keeping watch is mentioned, and the guy talks about being scared. It feels like the Super NES translator was racing through this line like a student rushing to finish their homework while the teacher is collecting it. The fan translation is a rephrasing of this faulty Super NES translation.

The GBA translation goes a slightly different direction with the translation, but the translator took it to mean that the whole town was shaking rather than just the man himself shivering. As far as I know, the Japanese phrase ブルブル (buruburu) is only used for people trembling/shivering/shuddering, so this feels like a mistranslation to me as well.

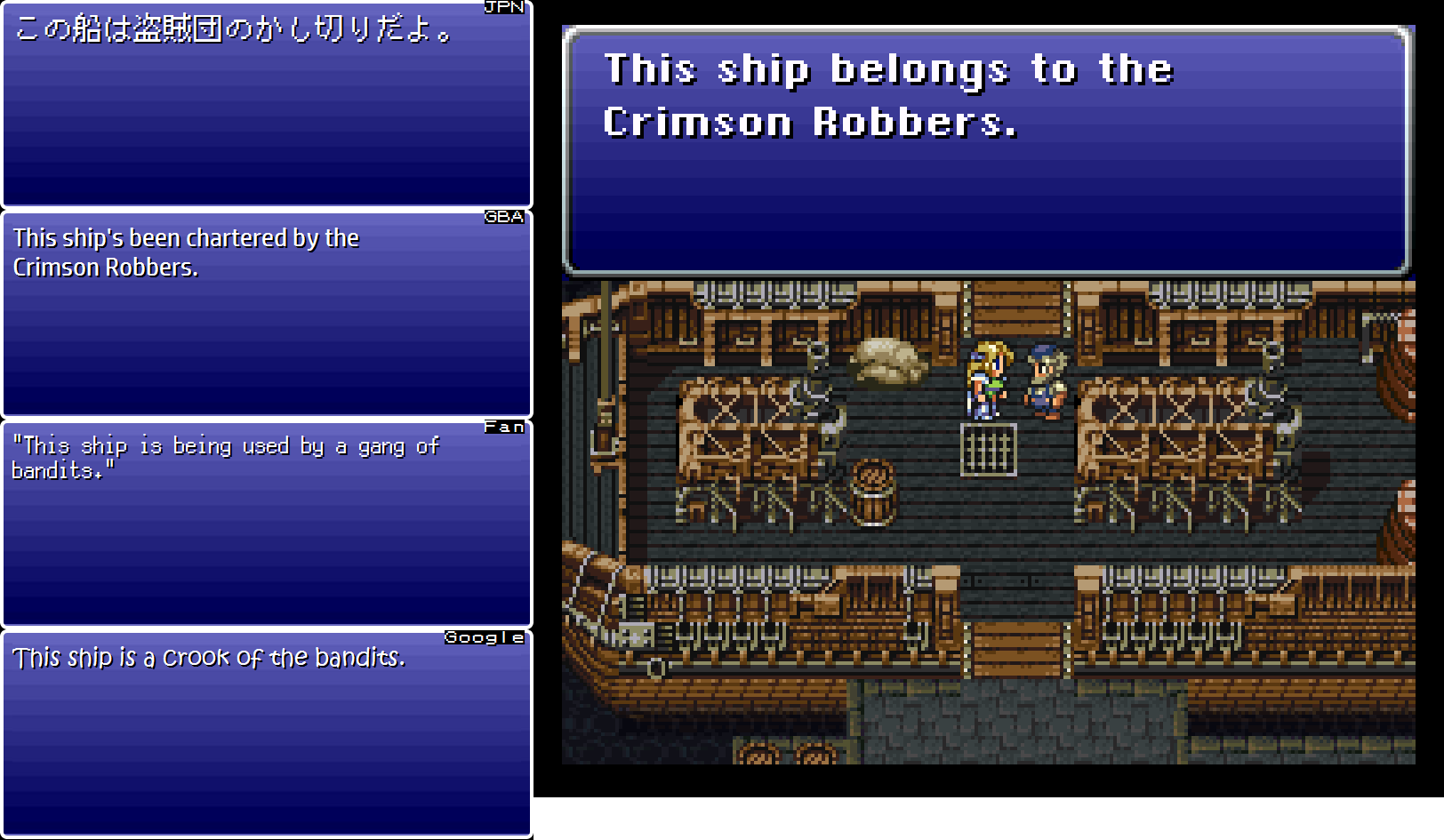

Crimson Robbers

A bunch of bandits team up to steal back their treasure from Castle Figaro. In the Super NES version, these bandits call themselves the “Crimson Robbers”. They don’t have a group name in the Japanese script, though – it was an addition by the Super NES translator. The GBA translation retains the new name.

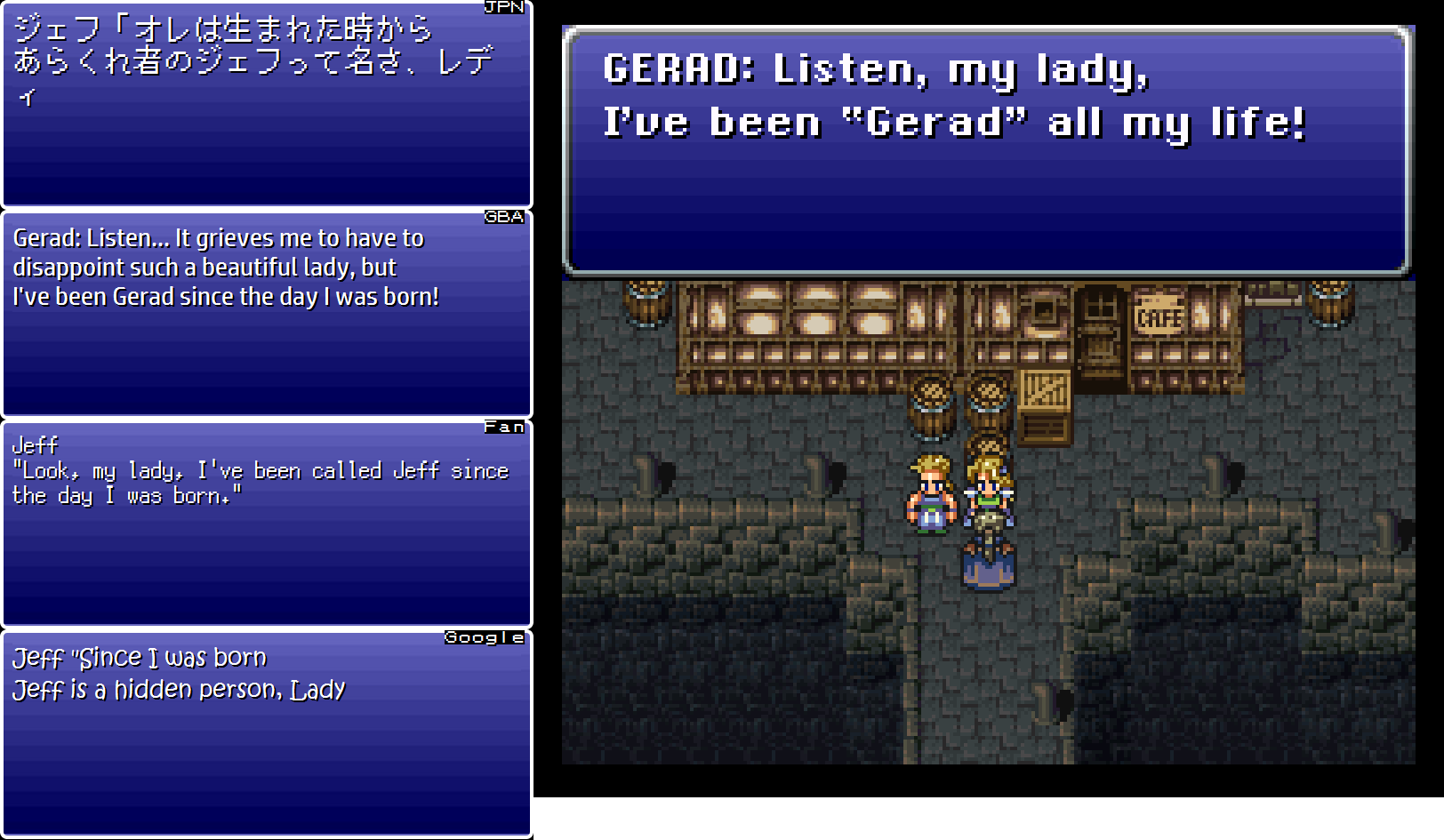

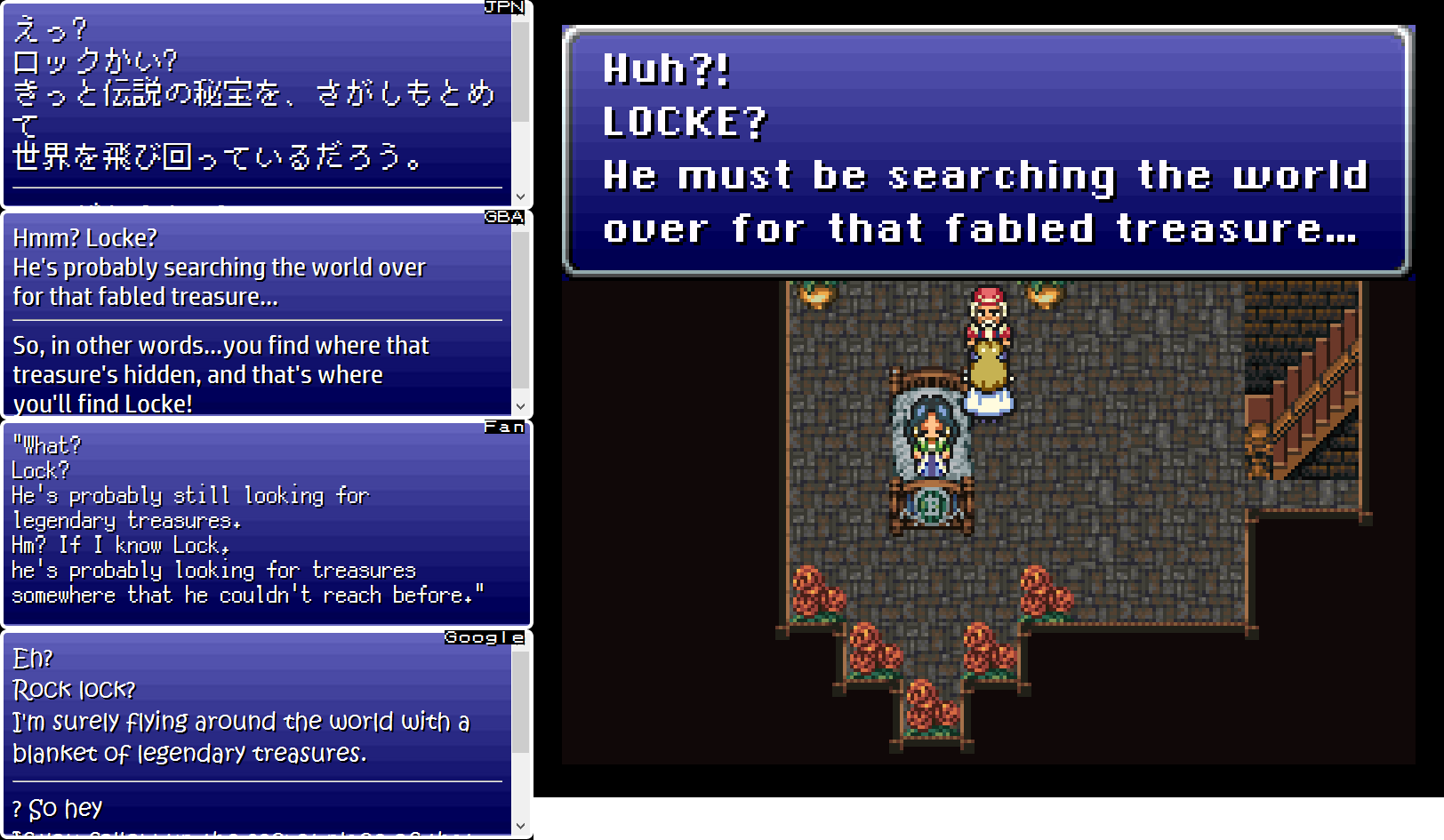

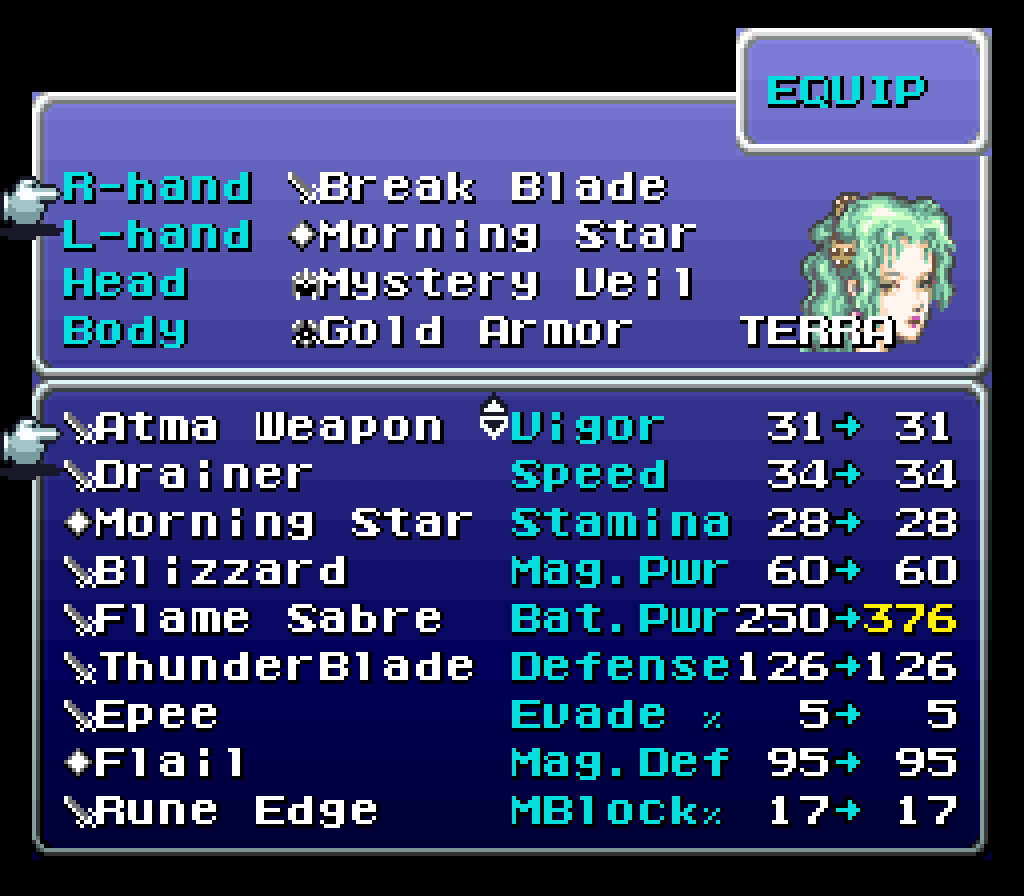

Edgar and Gerad

Edgar goes undercover and pretends not to be the king of Figaro for a short while. In Japanese, his fake name is “Jeff”. In the Super NES translation, he instead goes by “Gerad”, which astute players might recognize is “Edgar” with the letters rearranged. The GBA translator kept this “Gerad” name in the English GBA script. As a player, I feel that “Gerad” is more clever and has more creativity, and is arguably an example of a translation outdoing the original. But I wonder if there was a specific reason the Japanese writers chose the name “Jeff”.

On a separate note, Celes is able to see through Edgar’s disguise because he uses the English word “lady” when speaking in Japanese. Naturally, this stands out as a unique speech quirk in the Japanese script. But since the English translation has him speaking in English already, that same speech quirk wouldn’t work as well. So the Super NES version tweaks things a little and has Edgar use “my lady” instead:

Only Edgar would say, “my lady.”

In the GBA translation, she points out Edgar’s contradictory behavior in addition to the “lady” thing:

I’ve never met anyone else who’d flirt with a “lady” he was trying to shake off his tail…

This is a pretty minor thing and I almost didn’t mention it, but I figured it was a nice example of how seeing through unique speech traits requires extra work in translation.

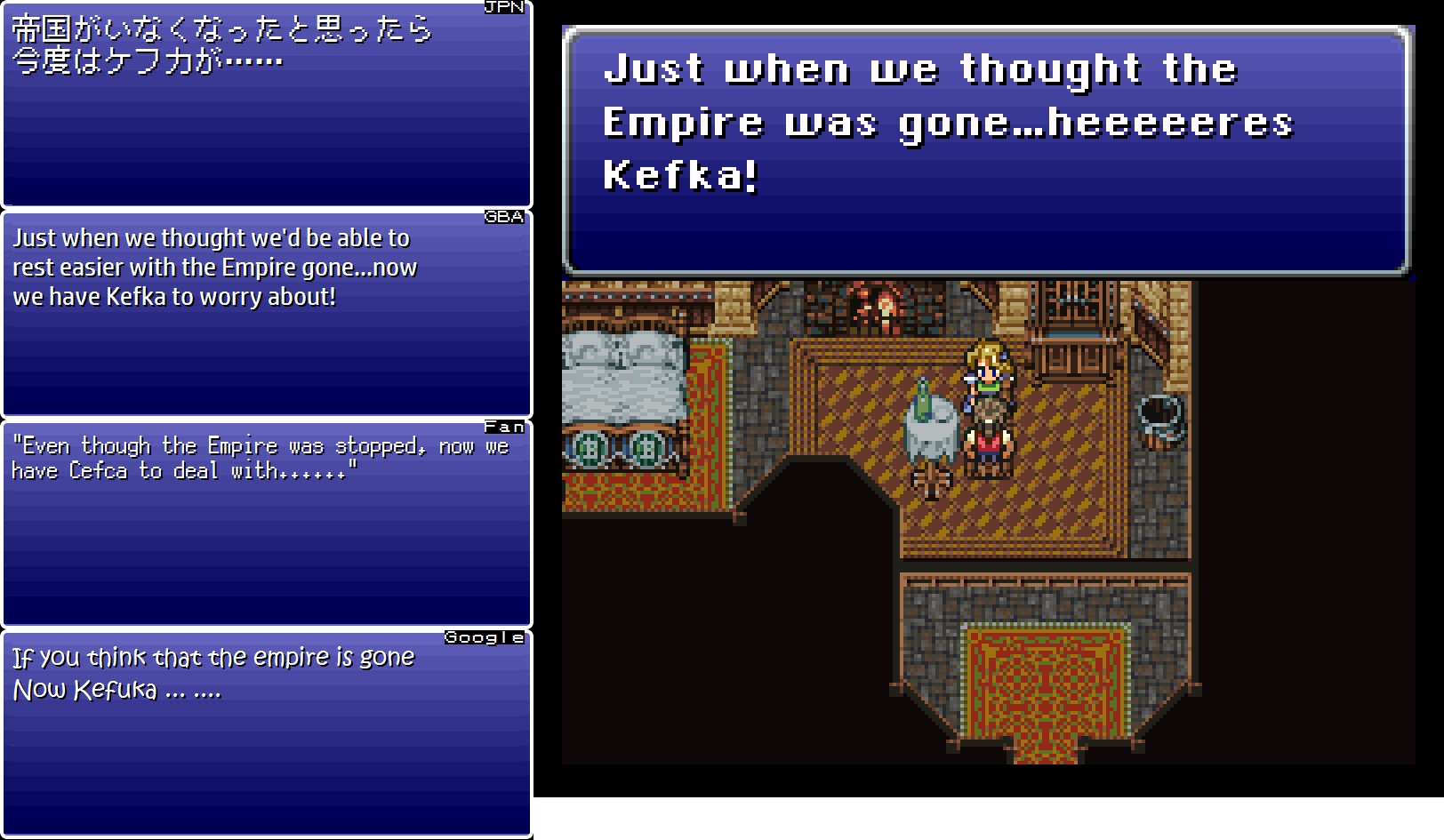

Here’s Reference

In Japanese, a man in South Figaro says something like:

Just when it seemed like we were rid of the Empire, now we have to worry about Kefka…

In the Super NES translation, this became:

Just when we thought the Empire was gone… heeeeeres Kefka!

Everyone in the stream chat seemed to agree that this was a reference to Johnny Carson and/or the Johnny Carson reference in The Shining:

This wouldn’t be the first pop culture reference to be inserted into the Super NES translation, as we’ve already seen. The GBA translation removes the reference.

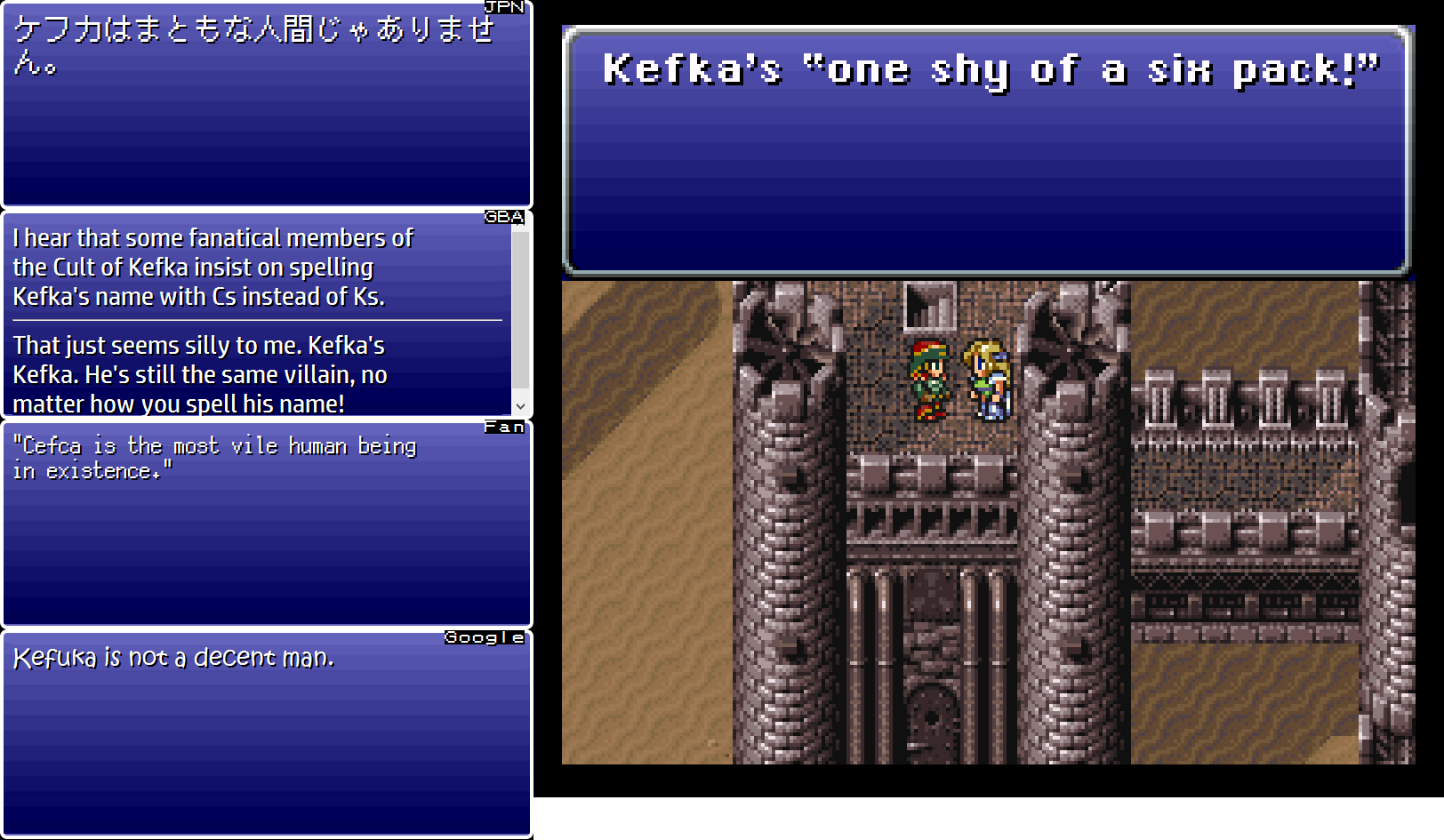

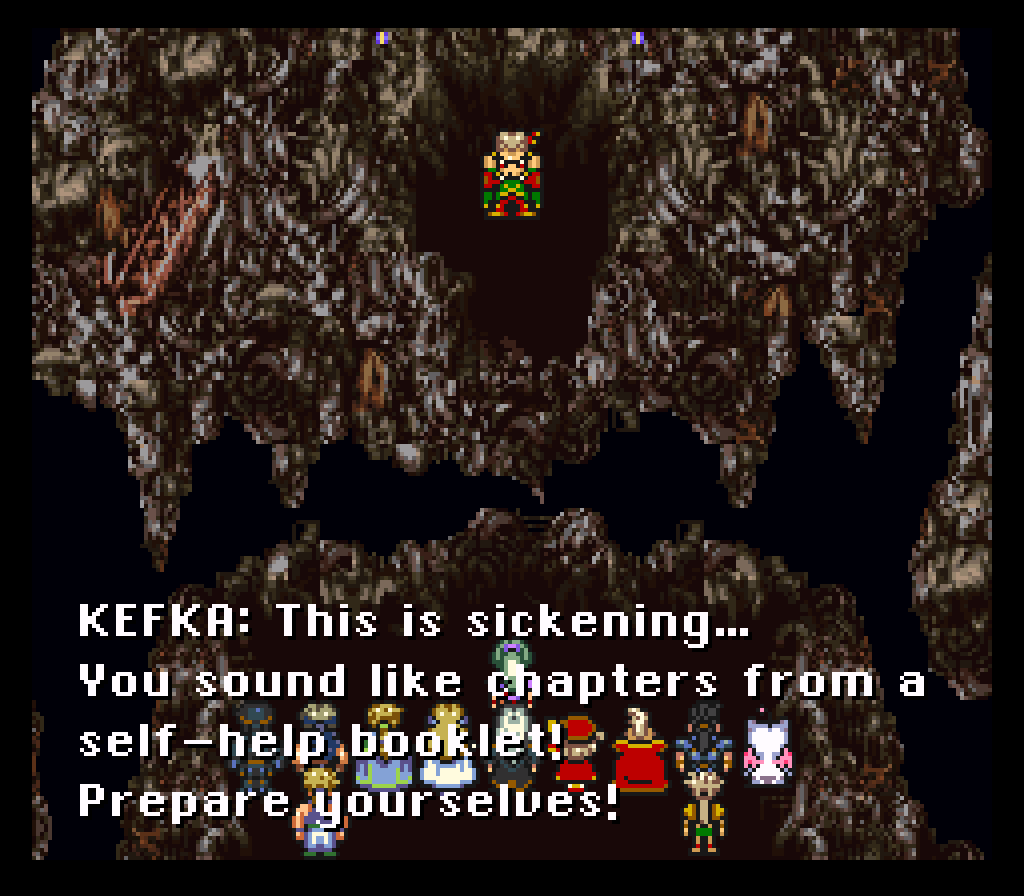

Kefka Talk

In Japanese, a soldier in Castle Figaro says something like:

Kefka is not a decent human being.

In the Super NES version, this was rewritten as:

Kefka’s “one shy of a six pack!”

This is a slang phrase that means that Kefka isn’t fully sane or isn’t fully there mentally. It also suggests that beverage “six packs” exist in the world of Final Fantasy VI. The localization choice here feels very similar to what you might expect from Working Designs at around the same time. It always felt kind of out of place to me, but it also always felt like a filler line anyway.

The GBA translation goes a very different route than the Super NES translation:

|  |

| Final Fantasy VI (GBA, Japanese) | Final Fantasy VI (GBA, English) |

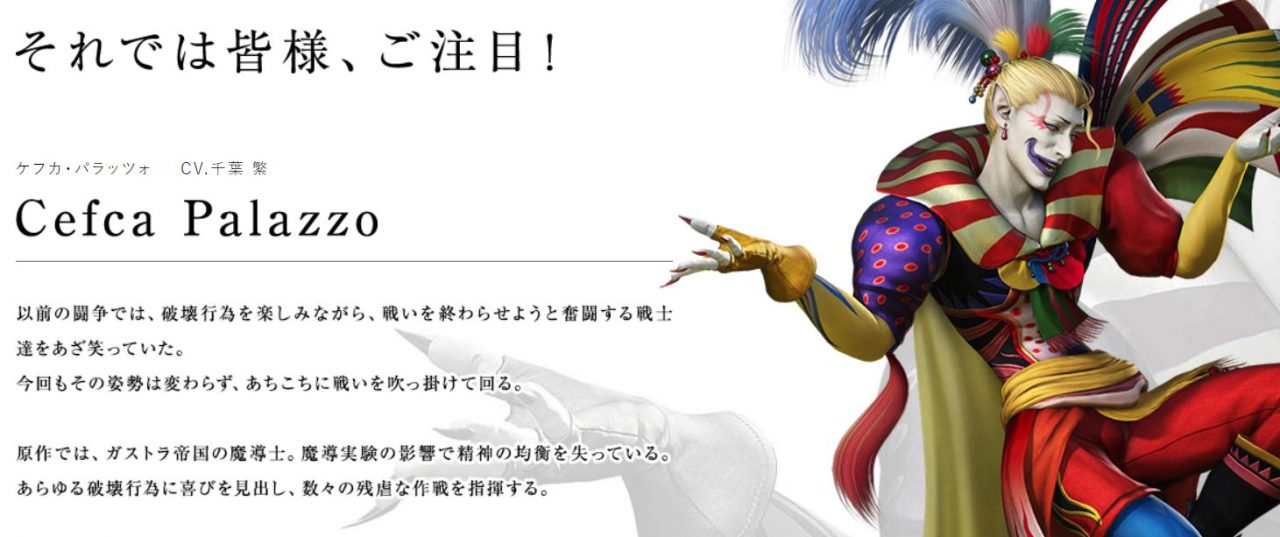

I hear that some fanatical members of the Cult of Kefka insist on spelling Kefka’s name with Cs instead of Ks.

That just seems silly to me. Kefka’s Kefka. He’s still the same villain, no matter how you spell his name!

I don’t know if the GBA translator has ever publicly commented on the matter, but this seems to be a clear stab at the “SkyRender” fan translation we’ve been looking at all this time. If so, then it’s one of the only times I can recall a professional translation referring to an unofficial translation – it’s almost like one translation is badmouthing another translation. I do know that modern Final Fantasy translations sometimes reference and/or poke fun at earlier translations, but this is on a whole different level.

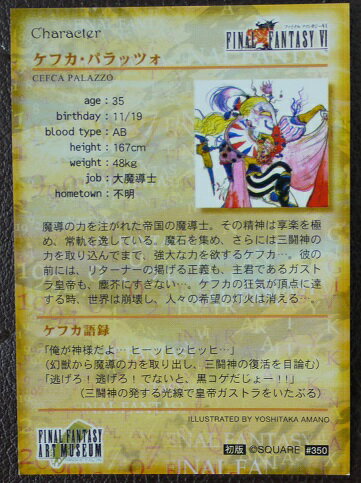

Of course, it’s entirely possible that it’s just a reference to the fact that Kefka’s name is spelled “Cefca” in Japanese materials. For example:

The fan translation uses the “Cefca” spelling because it appears in official Japanese materials, so it wasn’t pulled out of nowhere. But this fact makes it hard to tell with certainty what the GBA line is specifically referring to.

Incidentally, the fan translation translates this soldier’s line as:

Cefca is the most vile human being in existence.

This isn’t quite what the original text said. So, strangely enough, the Google translation gets closest to the original line.

This is also a great example of something I’ve learned over the years: sometimes the most bland, filler-like lines can be the most interesting to look at in translation!

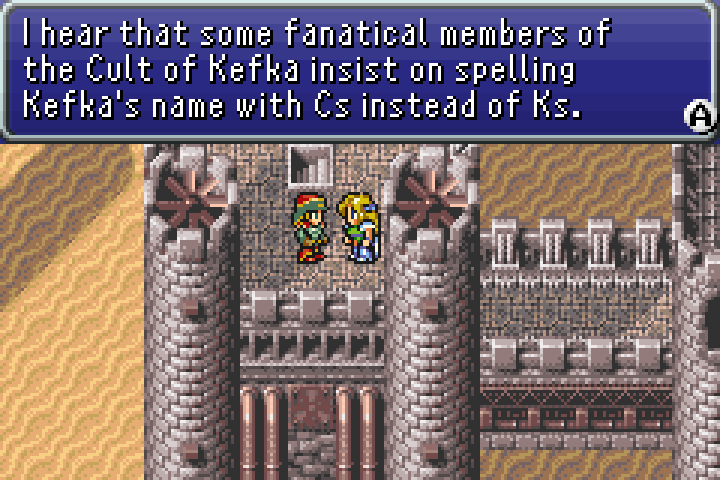

Siegfried’s Double?

We’ve looked at the confusion between “Siegfried” and “Ziegfried” in a few previous articles – the gist of it is that the Super NES translator appears to have translated the Japanese name ジークフリード (jīkufurīdo) inconsistently. Sometimes it was translated as “Ziegfried” and other times “Siegfried”. The inconsistency likely stemmed from the fact that the name is German, and German-to-Japanese name conversions don’t always follow the same patterns as English-to-Japanese name conversions. It would take a lot of time to explain things in further detail, but the short story is that going from German to Japanese to English makes “Ziegfried” a very plausible, understandable mistake.

In Japanese, Siegfried always goes by a single name. The GBA translation also only gives the character a single name. It’s all very straightforward and there’s been no confusion or inconsistency in the Japanese and GBA scripts so far.

Things do get strange at this point in the game, though. Siegfried appears in the coliseum and says in Japanese:

Apparently an imposter has been pretending to be me recently. Don’t be fooled.

Set aside the weirdness of the Super NES translation and consider this from the Japanese side of things. Why would Siegfried say this here and now? We’ve run into him multiple times in the past, he was always obsessed with treasure, Ultros confirmed that Siegfried was treasure-minded, and you can fight Siegfried in this coliseum for special treasure. What’s more, this mention of an imposter comes out of the blue, and nothing ever comes from it afterward. So, again, why would the game’s writers have him say this?

I’m not the only one who finds the whole thing mysterious, though – Japanese fans have brought up similar suspicions about this line too. One idea I’ve seen is that he’s just pretending there’s an impostor so you won’t harass him for taking all that treasure earlier. Another common theory I’ve seen is that more was planned for Siegfried and that there was going to be more content related to a fake Siegfried doing stuff, but then it got cut before the game’s release. I’m not sure what to think, but if I ever got a chance to ask the writers about Final Fantasy VI, this would definitely be one of the top questions I’d ask.

Regardless of how weird things seem or what Japanese fans think, two official Japanese books state that only the Siegfried in the coliseum is the real Siegfried.

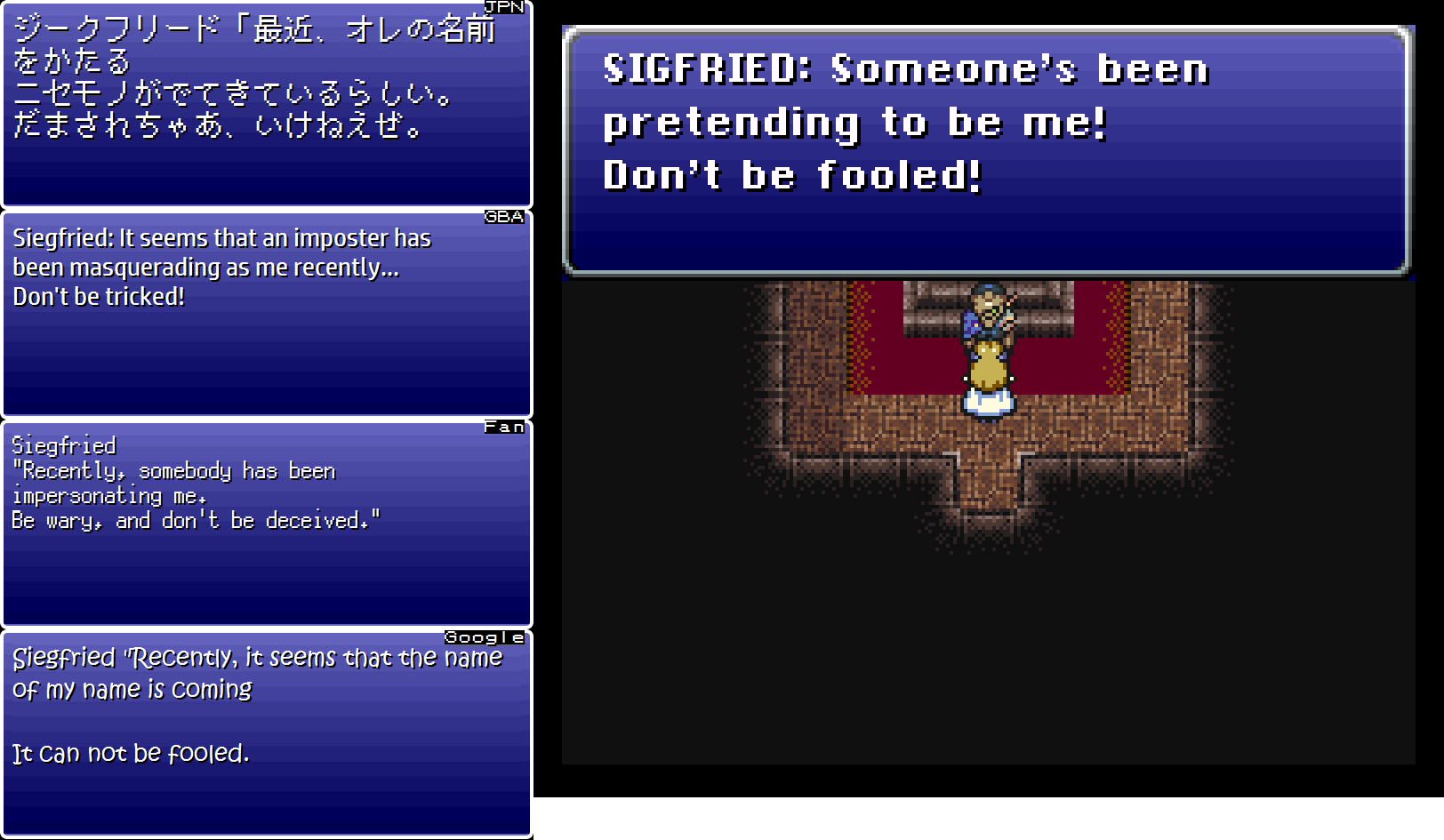

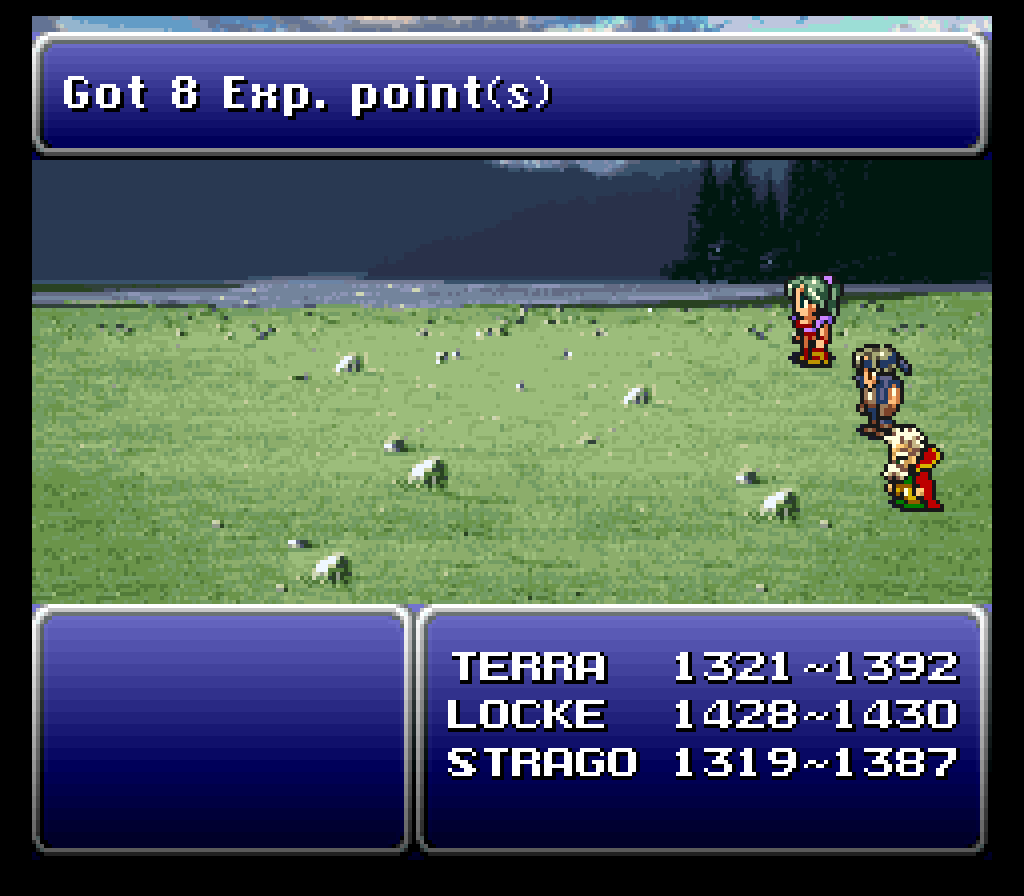

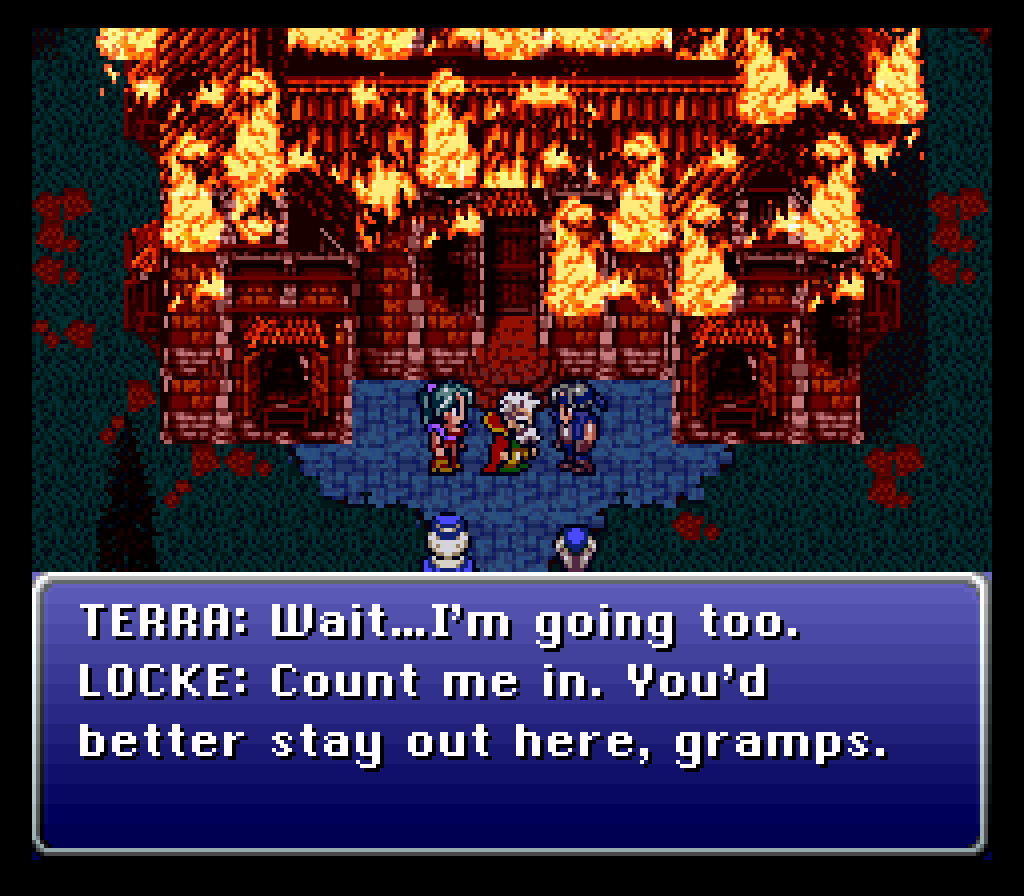

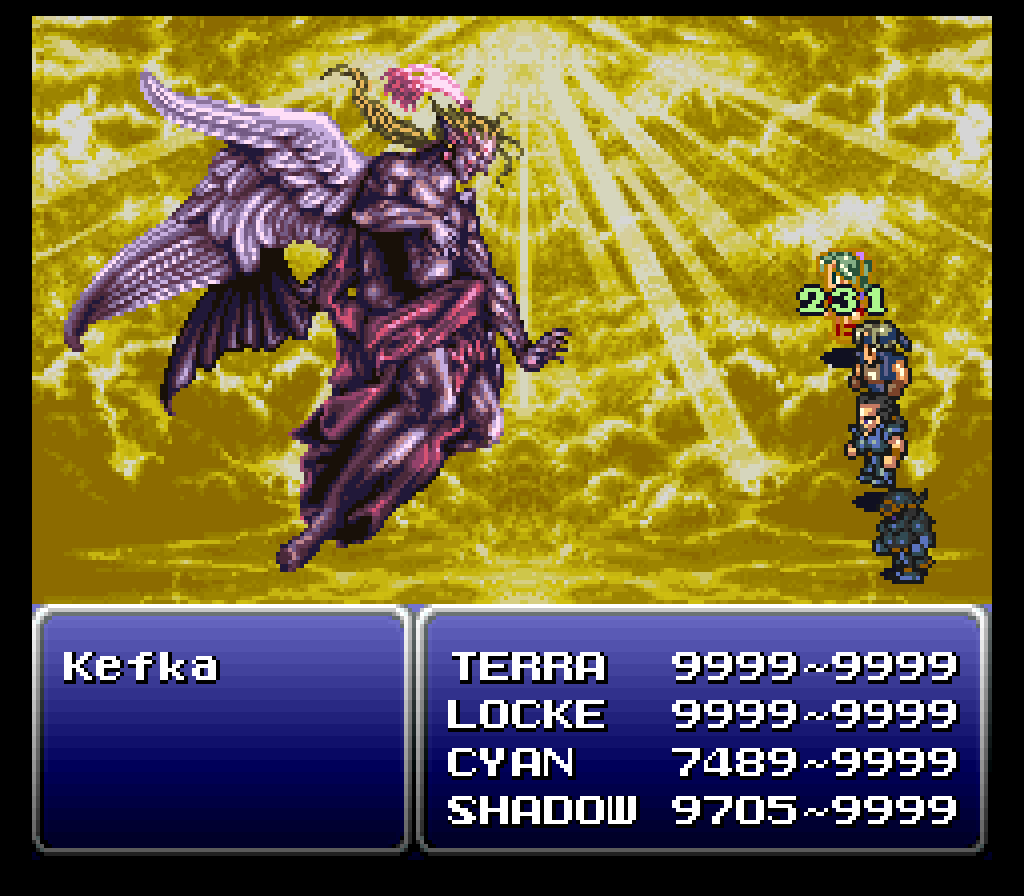

Locke’s Treasure

In previous articles we’ve seen how the Super NES translation has consistently mistranslated or cut out mention of a specific legendary treasure that Locke is searching for. Only now, about 60% into the game, does the Super NES script finally mention it. This makes it seem like Locke decided to hunt for the treasure after the world blew up, but no, he’s actually been searching for it the entire game.

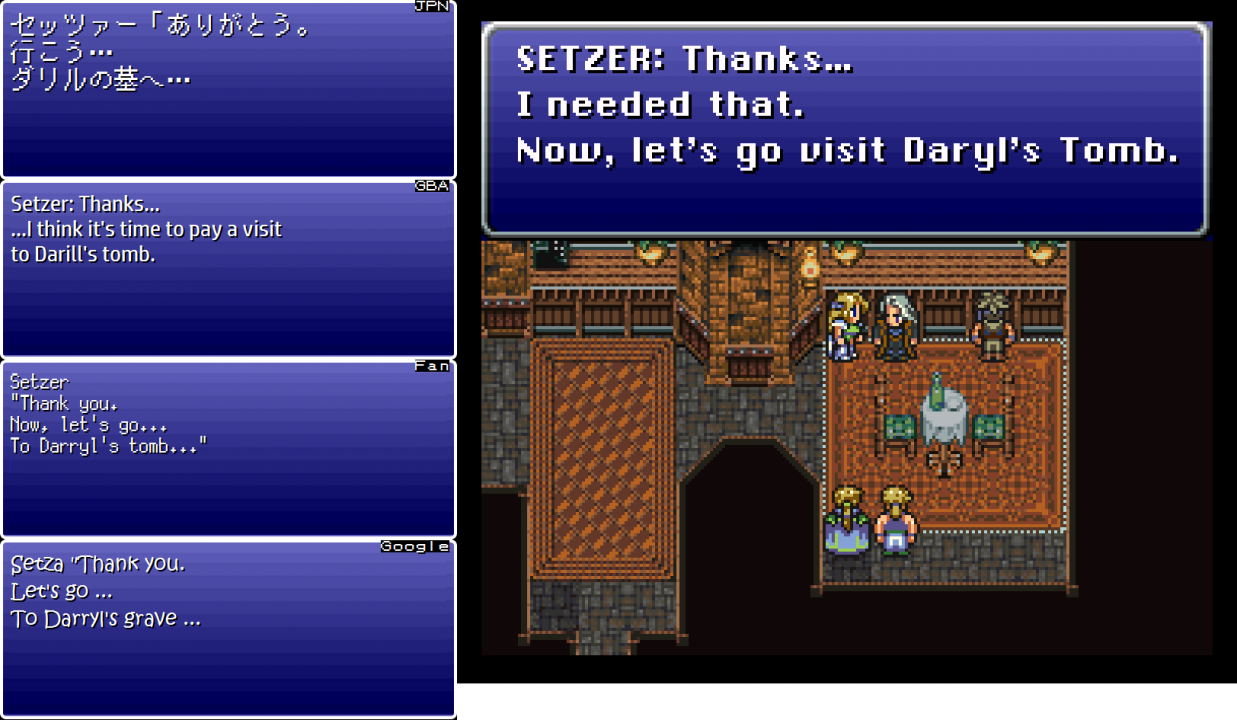

Daryl’s Tomb

We saw earlier how Daryl is spelled several different ways, depending on the version of the game you look at. Here, we see that even the Super NES translation can’t decide what to call it: in the main script it’s “Daryl” but in the secondary text it’s “Darill”.

Game text comes in different types: you got the main script, then you got menu text, battle text, special scene text, and lots more. Different types of text are usually stored in different places or as different files, so you usually end up with the main script text in one file and other menu-related text in other files. Because of this, and because different files are often translated at different points in time, it’s easy to make consistency mistakes like this if you’re not careful. In fact, this same phenomenon might be what caused the whole “Ziegfried” and “Siegfried” consistency problem mentioned above.

Rainbows and Flashes

If you use Setzer’s slot machine battle command and get three diamonds, it’ll produce an attack in Japanese called セブンフラッシュ (sebun furasshu). Because of the Japanese A/U spelling confusion problem, it’s hard to tell at first if this should be “Seven Flush” or “Seven Flash”. Here, we see that the Super NES translator went the “flush” route. The fan translator did the same.

I never though about this name much, but the actual attack involves rainbow-colored light that shoots upward out of the ground, so “Seven Flash” does seem more logical now that I think about it. So what’s the deal with “seven”? Wouldn’t it make more sense for this attack to be used if you get three 7s in the slot machine?

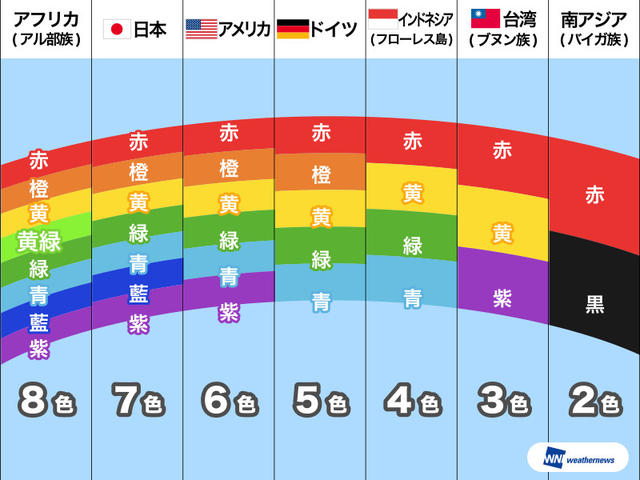

At this point in the stream, I explained that different cultures depict rainbows as having different colors. In Japan, rainbows are depicted as having seven colors, which for some reason I vaguely recall is a point of pride but I don’t remember why. I remember a big Japanese essay assignment I had long ago that was about this very topic, and that it seemed to focus on the fact that Japan uses more colors than most other countries, so maybe that’s what I’m thinking of.

Still, here’s a look at some Japanese infographics about this rainbow color stuff:

It always feels weird to me to categorize things as “Japan thinks this” and “America thinks this” and “Germany thinks this”, because we’re talking about millions of different people spread across wide regions. So chatters in the stream were like “wait, what? I learned ROY-G-BIV growing up, which is seven colors”, I was reminded of that feeling.

Anyway, the point I’m getting at is that in Japanese, the very phrase “seven colors” is synonymous with “the colors of the rainbow”. And since this “Seven Flash” attack happens when you get three diamonds, it’s referring to the prism effect. The GBA translator put all this background cultural information and scientific phenomenon together to reach a different name for the attack: “Prismatic Flash”.

Secret Password

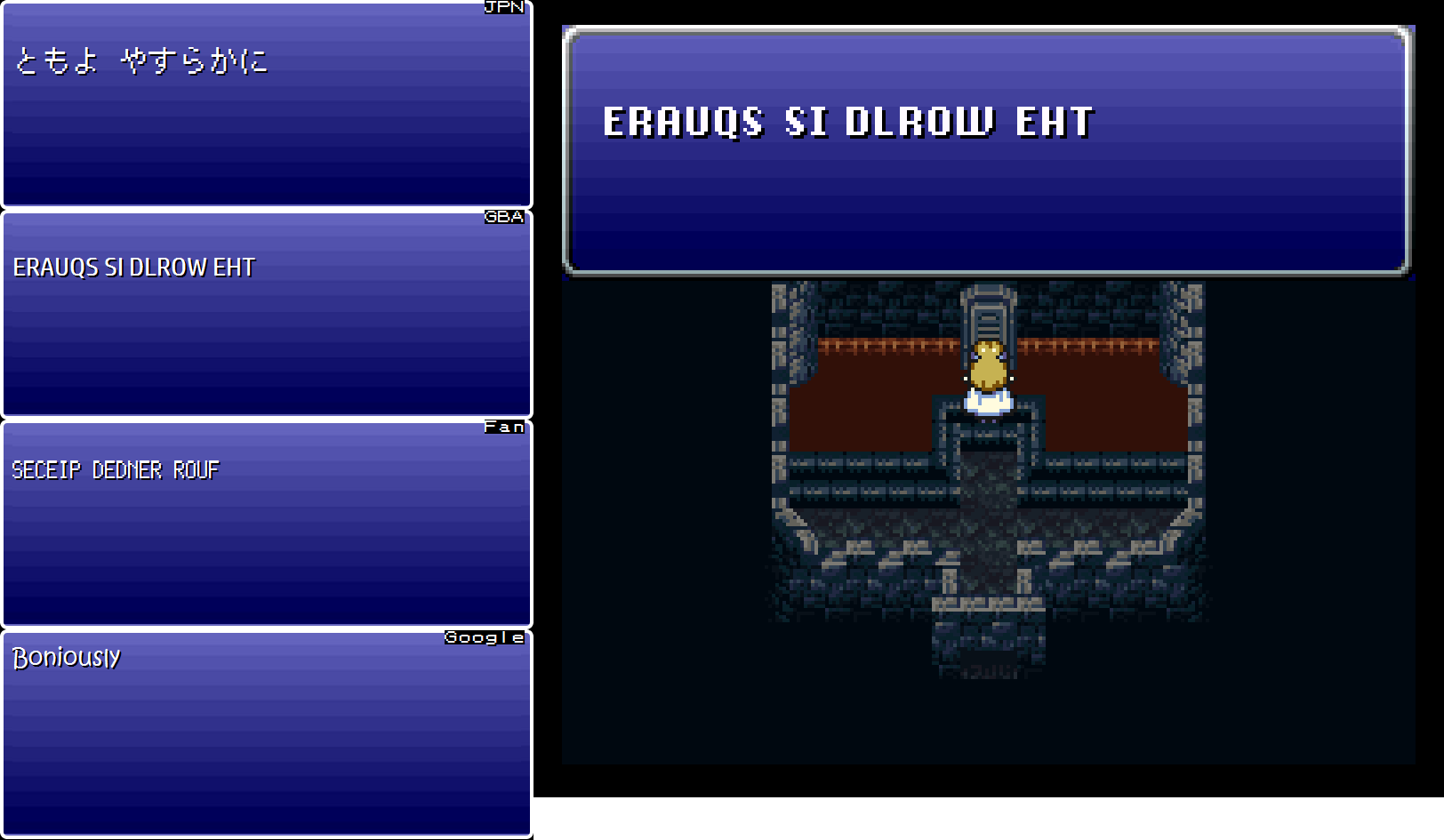

Darill’s Tomb has a password puzzle that leads to a helpful item. In Japanese, this password consists of four parts:

- yoya

- kani

- sura

- tomo

When put in a different order, the final result is tomoyoyasurakani, which means something like “Rest in peace, o friend”. And since this is the tomb of Setzer’s friend, the password makes perfect sense.

For the Super NES translation, the password was changed, and each piece of the password was written backwards to make it harder to tell what the password is. The final password ends up being: “ERAUQS SI DLROW EHT”, or “THE WORLD IS SQUARE” backwards. Someone in the chat mentioned that “The World is Square” was Squaresoft’s marketing slogan at the time, but I don’t recall that. At the time, I thought it was a clever joke about the company’s name and how the world map in Final Fantasy VI was square-like in shape.

The Super NES password became iconic and memorable among fans, so the GBA translation uses the same password.

The fan translation doesn’t stick with the theme of the original Japanese password, so the new password has nothing to do with a friend resting in peace. Instead, the fan translation does the same backwards text thing found in the Super NES translation, but with a different phrase: “FOUR RENDED PIECES”. Except the fan translators got it wrong – it actually says “FUOR RENDED PIECES” when you solve it!

And poor Google had no idea what was going on with any of this password stuff. I don’t think Google’s AI is at the level yet to recognize such word puzzles and use creativity to localize them.

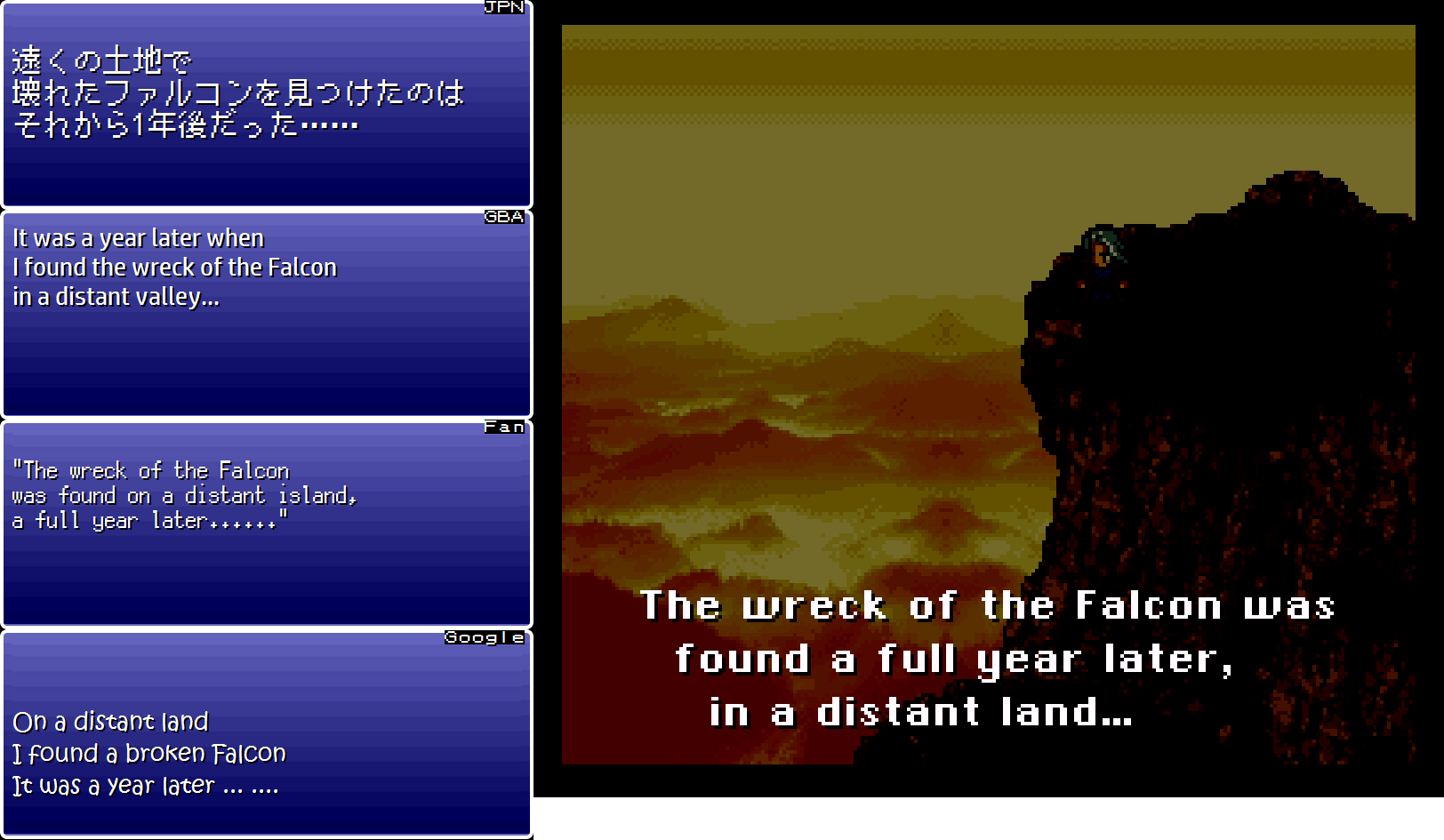

Falcon Wreckage

Setzer explains that Daryl, an old friend of his, died in an airship crash. During the explanation, he says in the Super NES translation:

The wreck of the Falcon was found a full year later, in a distant land…

Some chatters were curious about who found the airship. The original Japanese text doesn’t specify, but the verb used seems to imply that it was Setzer who found it. This is why the GBA translation uses “I” in the line while the Super NES and fan translations talk about it in the passive form.

The Japanese line also simply says it was found “in a distant land”, which the Super NES version keeps intact. For some reason, the GBA line says “in a distant valley” while the fan translation says “on a distant island”.

So again, despite the weird phrasing, the Google translation somehow manages to handle the details the best here. What’s going on anymore?!

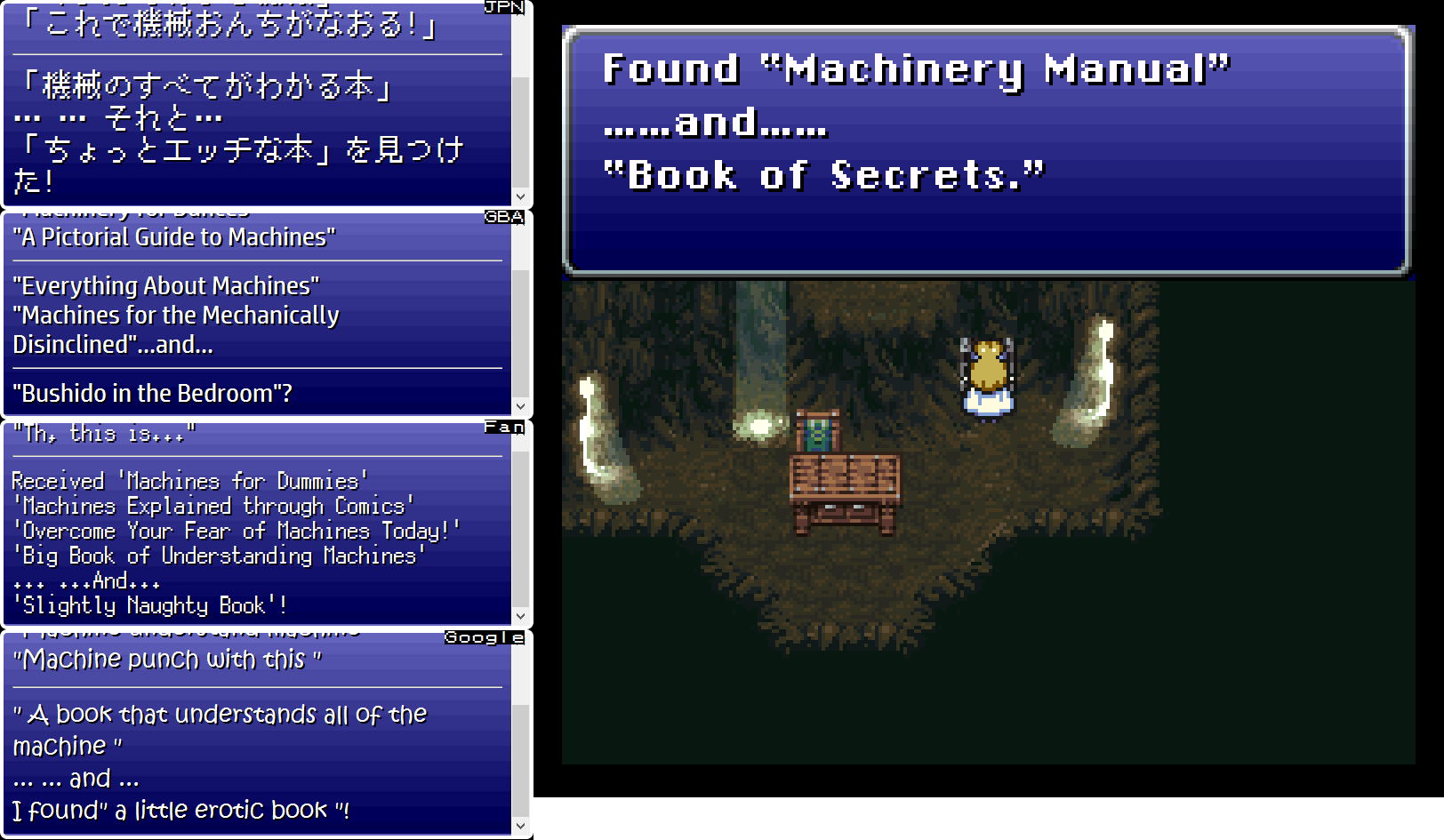

Cyan’s Extra Book

Cyan has a bunch of books about machines locked away in a treasure chest. If you find the key and look inside, you’ll find that the final book is on a different topic.

In Japanese, this extra book is called something like a “Slightly Naughty Book” or “Slightly Erotic Book”. This playfulness wouldn’t fly with Nintendo of America’s content policies, so the book was renamed the “Book of Secrets” in the Super NES version. When I first played the game, I think I assumed this was about secret techniques or something, so the original joke was lost on me for a long time.

The GBA version was allowed to handle this sort of content more openly, so the localizer gave it a more creative name: “Bushido in the Bedroom”.

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/bbenma.png)

The official map that came with FF3 SNES laid out the World of Balance on one side and the World of Ruin (both so labeled) on the other. I suppose people didn’t worry as much about spoilers back then.

Nintendo Power’s walkthrough over three issues (October – December 1994) also used the terms extensively. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who read those issues over and over before Christmas that year.

Another vote for the included map, it was packaged with the game and included both names, I know that’s where I first got it from.

Another for the map. I still have mine, actually…

By the time this game came out, Nintendo’s censorship practices were widely known. After years of subtle but observable probable changes (e.g. always “defeat” instead of “kill”, bars always serving milk or soda), things came to a head in 1993 when the SNES port of Mortal Kombat replaced blood with gray “sweat”. Therefore, to me, the context of Celes’ attempted suicide and the text mismatch were rather obvious. I recall finding the text laughable, like I was reading a dark comedy.

An anecdote as to when I became aware of Nintendo’s censorship policies, it was when I encountered a game where things fell through: Golgo 13: Top Secret Episode in 1988 or 1989. Despite calling him a “secret agent” in either/both the manual and/or game intro, he was very obviously an assassin and may have even been referred to as such somewhere in the game. They left in a sex scene (in silhouette), which has since become semi-famous due to it escaping censorship. This game, along with Metal Gear, feature cigarettes. Human NPCs were very obviously assassinated in your presence. All in all the game had a PG-13 feel to it in an era of G up to soft-PG games. As a result, the game has a certain nostalgia to it despite being just an average quality manga licence game. Something else that stuck out was the game leaving the Golgo katakana (ゴルゴ) as-is on the transition screens.

There’s actually an LA Times article where an NoA executive says the outrage over Mortal Kombat’s censorship is what finally killed that non-sense (at least until 2013. Then Nintendo’s censorship became even more insane than it was in the NES/early SNES days. They required a third party title censor SWORDS.).

http://articles.latimes.com/1994-09-09/business/fi-36631_1_mortal-kombat-ii

Wait, what game was that? That’s news to me.

I know Dragon Ball Fusions has swords changed to sticks. Which makes no sense at all considering how many sword titles there are in the 3DS library alone!

That wasn’t Nintendo that made that change, though.

Lol, I remember when I first played the game, i practically died laughing at the “Bushido in the Bedroom” joke. It’s such a clever way of implying something dirty while also tying into Cyan’s samurai background.

Yeah, and I would definitely consider it an improvement to something as boring and non-specific as something like “slightly naughty book”!

I kind of thought it was a little crass and off-kilter for Cyan to be lugging around an adult book. I get the point is the contradiction between a character who publicly shoos away even a hint impropriety and his engagement of lewd acts, but it seems like a cheap, awkward add-on, given how serious and pervasive Cyan’s issues are, to the point where he has TWO side-quests related to them. It’s even more jarring when intimacy is handled metaphorically or offscreen; even Edgar’s flirting is relatively chaste.

I don’t necessarily agree with all instances of censorship, but I fully agree with that one.

The characters in this game are great because they’re not just stereotypes of some kind of attitude, I think. This is a middle-aged soldier who’s been ripped away from everyone he loved for most of his life, reaching out for intimacy in a way he’s ashamed to need, in a dark and damaged world. Let him read playboys in his cave

To add onto this, you can only find the magazine after you learn that Cyan has been sending letters to Lola as her dead boyfriend. The smutty magazine makes an interesting contrast to Cyan’s well-meaning, yet misguided task.

It certainly has a little more depth than your typical porno mag gag.

I agree. In addition to being a silly one-off gag, there’s a bit of poignancy here; Cyan is lonely, but instead of emo moping about, he puts on a brave face and we get little glimpses occasionally.

Also, since it’s a “slightly naughty book”, I think we’re really talking more like a Sears catalog than a Playboy. Or, to match it to Cyan’s character, maybe it’s a book of courtly romance that gets a little bit more detailed than one might expect.

Oh yeah, that makes the most sense! It’s not a porno magazine, it’s a romance novel, with heaving bosoms and all the cliches. Smutty, but slightly high-brow.

Cheap sexual humour is something that Japanese games seem to have always been rife with and in many cases it has only gotten more pervasive with time. It’s something I’m very hit or miss with so I can definitley agree with you here.

I’m pretty sure that this kind of ‘random book of very much adult nature’ has been a running gag in the series ever since FFIV, so that might clear something up.

I think what those Japanese graphics are trying to get at is less about how different cultures learn about the rainbow and more about how many color words those cultures have in common usage. The whole “color words” thing is a topic you’ll hear about in linguistic anthropology, kind of a proxy for the larger question of how the words we use and the way we perceive reality affect each other (and probably leading into the phrase “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis” eventually…).

Point is, even though English speakers learn the “ROYGBIV” thing for the rainbow, “indigo” isn’t really a color term we use very often in casual speech, so we only routinely talk about the other six colors. Those graphics seem to be claiming that Japanese has fairly basic words for all seven of those colors.

That seems a little incongruous with what I’ve learned about the Japanese language historically not distinguishing between what the English language calls “blue” and “green”.

Japanese refers to the rainbow color we know as indigo as “ao” (standard word for blue) and the rainbow color we know as blue as “mizuiro” (literally “water color”, a lighter shade of blue that doesn’t really have a unique name in English beyond “light blue”). The word mizuiro is a lot more commonly used in Japanese than the word indigo is in English, but it’s nowhere near as common as the words for the other six colors of the rainbow. So eh, I dunno.

…that’s what wikipedia says, at least, the infographs posted above claim Japan uses “blue” and “indigo” just like we do, and that most other countries don’t acknowledge indigo. The Japanese word for indigo is “aiiro”, which is not any more common than “indigo” is in English.

Isn’t it nice when sources agree?

Just for fun, the kanji that first graphic uses for the colors, and their frequency in newspaper use according to Jisho, as compared to the frequency of the corresponding English word according to this table: https://www.wordfrequency.info/free.asp?s=y

赤 (*aka*, 584/2500) versus “red” (598/5000)

橙 (*daidai*, x/2500) versus “orange” (3303/5000)

黃 (*ki*, 1240/2500) versus “yellow” (1675/5000)

緑 (*midori*, 1180/2500) versus “green” (893/5000)

青 (*ao*, 589/2500) versus “blue” (845/5000)

藍 (*ai*, 2043/2500) versus “indigo” (x/5000)

紫 (*murasaki*, 1516/2500) versus “purple” (3931/5000)

Notes:

* Comparing isolated kanji to complete words isn’t exactly the best methodology, but it’s the fastest approach.

* The kanji 藍 isn’t all that common, but common enough to at least show up on the top 2500. English “indigo” doesn’t make the top 5000 at all.

* English “violet” isn’t in the top 5000, but “purple” is synonymous.

* Surprisingly, the kanji the graphic chose for orange, 橙, actually seems to be fairly obscure; it’s not on the newspaper list, and it’s classified as a jinmeiyou (proper names only) kanji. The word 橙色 (*daidaiiro*, “the color orange”) is tagged as a “common word” by Jisho, though… I guess they more commonly write it in kana?

* In the couple of song lyrics I’ve seen that talk about something orange, they just use オレンジ (*orenji*, as in the English word “orange”).

* The normal pattern that linguists have been picking up on recently is that words for warm colors are more common than words for cool colors. (See here, for example: https://theconversation.com/languages-dont-all-have-the-same-number-of-terms-for-colors-scientists-have-a-new-theory-why-84117) Orange seems to break that pattern in both English and Japanese… I guess it’s not all that common for people to need to distinguish something orange from something red or yellow.

The way 青 (ao) is interpreted seems to depend heavily on what other colors are present for it to be compared to. It occurred to me as well that the color the charts label as 青 is a color that I’ve often seen referred to as 「水色」 (mizuiro, which I think would be reasonable to translate as “sky blue” in English, even though the Japanese word is comparing a color to the sea instead of the sky,) and in materials where both 青 and 水色 are used, I’ve seen 青 refer to the same color that’s labeled as 藍 (ai) in these charts.

And, as someone else brought up, historically, the colors that were thought of as being part of 青 were defined much more broadly; 青 was closely associated with newly grown plants and fresh vegetables, and it included colors that, today, would be described as 緑 (midori/green.) 青 was used as part of the Japanese language for centuries before 緑 was introduced, and because of historical precedent, it’s still used in words like 「青野菜」 (a word for “green vegetables” that literally translates as “blue vegetables”.) Or, when talking about someone’s face turning pale, 「青い」 is used, and in that sense, it’s meant to be interpreted as just “pale” instead of conveying a hue at all.

There was a popular Youtube video going around a while ago where a guy was ranting about why the names of different animals were stupid, and he said that animals like red foxes and red pandas were obviously orange instead of red. But the word “orange” as a color is a relatively new addition to the English language (it referred to a fruit before it referred to a color,) so I think there are things in English that are referred to as being “red” just because that’s how they were described historically, just like how the colors of some things in Japanese are described as 青 instead of 緑 because that’s how they’ve always been described.

There’s a concept in linguistics called prototype theory, where it’s argued that people think of specific things as being central examples of what words refer to, which are generally the examples that are most familiar to them, and the words they use to describe things are not determined by a checklist of necessary attributes (a stone fortification built during the Middle Ages in a strategically important location to serve as a military base of operations is a castle,) but rather, which of these prototypical concepts the thing resembles most (a building that looks like the castles I saw in Disney movies growing up is a castle.) Which actually suggests that Neuschwanstein Castle is the prototype of all castles (linguistically, not historically, as it was built centuries after castles ceased to be used in any military capacity.)

In biology, mammals, birds and fish are all classified as animals because of the physical features they have in common, but in casual speech, when people describe something as an “animal”, they almost always mean it’s a mammal. This seems to be because people have a concept of a prototypical “animal” that’s basically a dog; it has four legs, fur, and a snout and it lives on land, so they think of “animals” as being organisms that share those qualities. They also have prototypical concepts of what a bird and a fish are supposed to be like (they might look like a sparrow and a trout,) so when they see something that looks like their prototypical bird, the word “bird” comes to mind instead of “animal”, even though biologically, they’re part of the same group. I suspect the color that Japanese culture thinks of as being the prototypical 青 is a pale shade of blue, and the color that American culture thinks of as being the prototypical “blue” is a deep shade, even though both of those words can be used to describe a wide range of colors that resemble the prototypes more than they resemble the prototypical colors that other basic color words refer to.

Wait is that why Anne of Green Gables describes the title character’s hair as being as “red as carrots”? I know carrots come in a variety of colors but none of them are red. Though by the time the books were written both the orange carrot and the color orange were well known. How long did this overlap last for?

I’d suggest that may be a bit of wry humor, since “red” hair isn’t anything resembling red.

Well, I suppose it’s an appropriate comparison, since red hair isn’t actually scarlet red any more than carrots are. It’s kind of like Douglas Adams writing “The ships hung in the sky in much the same way that bricks don’t.”

Orange and red did not have distinct names for each in English until fairly recently. I don’t have sources.

I thought Japanese for “indigo” was “aoshi”. You learn something new every day!

Aoshi is an archaic form of aoi, the adjectival form of ao.

Well, the word “aqua” is a somewhat common English term for light blues…

“Aqua” being English for mizuiro is such a common misconception the Japanese wikipedia article actually specifically points out that this is not the case. I believe it’s even snuck into print dictionaries.

Yeah, there’s a surprising amount written about how different languages divide up colors, and what kinds of colors they prioritize having words for, like if there are only 4 basic color words a language uses, which ones they’re likely to be, and I think that provides some interesting insight into how we perceive colors.

What I really wonder is whether it’s true that the Bunun people (who are apparently what 「ブヌン族」 in one of those color comparisons refers to) think of the prototypical colors that make up the rainbow as colors that native speakers of other languages would describe as “red”, “yellow”, and “purple”, or 赤, 黄, and 紫. That one stands out to me, because it actually goes against everything I’ve ever seen written about this subject, both from a linguistics perspective (most comparisons come to the conclusion that languages consistently incorporate basic color words that correspond to “white”, “black”, “red”, “yellow”, “green”, and “blue” in English before they incorporate any of the less common color words like “purple”, “brown”, and “orange”,) and from a physiology perspective (human eyes are more sensitive to some wavelengths of light than others, and the wavelength they’re most sensitive to is 555 nm, which is a hue native English speakers would probably describe as “lime green”. There are a suprising number of things in electronics specifically designed around this, for instance, digital cameras are typically made with sensors designed to detect three different wavelengths of light, which can be labeled in English as “red”, “green”, and “blue”, but they’re actually made with twice as many “green” sensors as “red” or “blue” sensors, because your eyes can detect more gradations of “green” light than “red” or “blue” light, so “green” light has to be measured more precisely for the color balance in a photograph to look accurate to you.)

Could that be a product of a methodological error on some anthropologist’s part? Is it possible that the Bunun people would really describe both “yellow”/黄 and “green”/緑 in terms of the same prototypical color that doesn’t correspond exactly to either, and someone, just because they asked the Bunun what word they would use for a “yellow” object before they asked about a “green” object, thought of the word they responded with as being “yellow”, even though that didn’t really match the color the Bunun were thinking about?

(Is “yellow” still a real word? Did anyone ever really think the Coldplay song “Yellow” was good? I don’t even know anymore.)

No Coldplay song was good.

That’s some odd logic, considering the wild/false indigo flower exists, and don’t forget the Indigo Girls. I’ve used indigo a lot when I refer to colors on clothes or a friend’s makeup. I’d say it’s pretty casual.

I literally spat out my drink when I read that in the Japanese version Edgar’s secret, undercover alias was…. “Jeff”.

Names like Jeff as well as Maxim’s son being called Ralph in the Japanese version of Lufia II are exotic to Japanese ears. They’re plain everyday names to you and me, but even a simple name like Jim lends a non-Japanese touch. Not like any of the cast are Japanese anyway.

I noticed a few things in the past few streams:

1) For the worms in the Figaro castle basement, they all have different status immunities and weaknesses. So you could bio-blast them at the start and poison at least one, while you could cast Death on another.

American kids would not ever think to try this, but Japanese players who had played FF5 WOULD, because there are multiple battles in FF5 that would’ve educated people on the multiple-enemy/multiple-weakness idea.

Basically, we had it harder here in the US because we hadn’t had the experience with the logical progression of FF battle tactics.

2) The Cruller / Du du fe du enemy. It’s named Cruller probably because the sprite looks a bit like a twisty donut, but as for the real name, that’s a mystery.

A google of ドゥドゥフェドゥ produces several Japanese fan sites that don’t really understand what the name is supposed to be either. One theory is that it could be “due to fade.” The reason that makes sense is that the sprite swapped enemy, Enuo, is the English N-O spelled out, according to the wiki. This could mean the dudefadu is supposed to be a transliteration too. A different theory is that it could be a song reference, but I don’t get how it relates to an intestine monster. Maybe stomach gurgle noises?

3) Seigfried’s imposter. I always assumed it was just a line of dialogue to warn players that challenging him in the Coliseum won’t be the same joke as it was back on the Phantom Train. Since they cut whatever identity-theft plot that was supposed to happen (maybe the original Gogo sidequest?) they could have just tossed in this line to explain away the earlier strangeness.

4) The Antesansan / Exoray. Like I did above, looking up the Japanese name gives theories. The one I think has most merit is that it’s something like “Anti-Sunshine”, which would fit the gloomy-flower look.

5) Mad Oscar is definitely Woolsey looking at the sprite and thinking it looked like Oscar the Grouch.

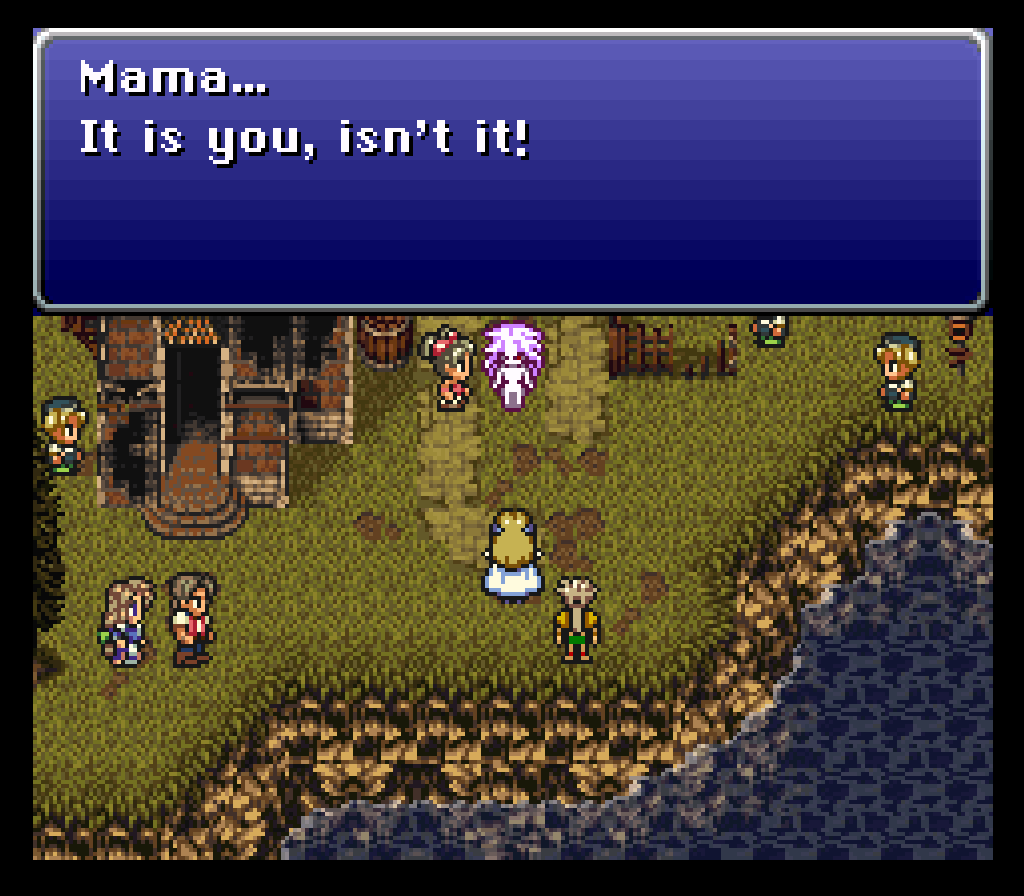

6) For Gau’s father, be sure to have the right characters for the best scene. As per the wiki:

“To see the full version of the armor shop scene where the party dresses Gau up to go meet his father, the player must have both Locke and Edgar in the party, while Terra, Celes, Cyan and Setzer must be waiting in the Falcon. ”

7) The moment has long passed, but I assume you know that Gau has special dialogue for if he is alone and speaking to Ramuh back in Zozo? May be interesting to see how the Japanese wrote that scene.

Addendum: if you look at this page of unused FF6 dialogue, you can see more evidence that Seigfried’s imposter was the first one you encounter:

finalfantasy.wikia.com/wiki/List_of_Final_Fantasy_VI_dummied_content

Siegfried: It seems that someone has been masquerading as me on a little plundering rampage lately…Don’t be tricked! Good treasure finds YOU, I always say. Well, let’s get on with this, shall we?

That was always my impression about Siegfried, too. I got the impression that the thief (Treasure Hunter?) Siegfried was a sham that was trying to use an intimidating name to shoo people off. After all, the first time you meet him he tries to do that: lays claim to a treasure chest and tries to intimidate the party with a bold name and claim. I got the impression that the Coliseum Siegfried was the real one.

So since it didn’t get mentioned before, if you go back to Maranda after Empire’s soldiers has left it(in world of balance after banquet), the girl who was chased around seems to be disappointed that soldier isn’t there anymore.

I’m wondering since in translated version she was interested in marriage if that was also mistranslation/changed or if that was case in Japanese version too

He mentioned it in an earlier section, but I always got the impression that the woman wanted to get married, not the other way around. That may have been a mistranslation, but that was always how I thought of it.

Personally, I always thought “7-Flush” was a reference to a poker flush, which seemed appropriate given Setzer’s “profession”. Of course, since it comes from a slot machine, maybe that doesn’t hold up…

I’ve played slot-machines that use poker terminology before. I think it’s pretty common. I’m certain that it’s a poker reference; I can’t see what else it could even be.

Just for fun, the kanji that first graphic uses for the colors, and their frequency in newspaper use according to Jisho, as compared to the frequency of the corresponding English word according to this table: https://www.wordfrequency.info/free.asp?s=y

赤 (*aka*, 584/2500) versus “red” (598/5000)

橙 (*daidai*, x/2500) versus “orange” (3303/5000)

黃 (*ki*, 1240/2500) versus “yellow” (1675/5000)

緑 (*midori*, 1180/2500) versus “green” (893/5000)

青 (*ao*, 589/2500) versus “blue” (845/5000)

藍 (*ai*, 2043/2500) versus “indigo” (x/5000)

紫 (*murasaki*, 1516/2500) versus “purple” (3931/5000)

Notes:

* Comparing isolated kanji to complete words isn’t exactly the best methodology, but it’s the fastest approach.

* The kanji 藍 isn’t all that common, but common enough to at least show up on the top 2500. English “indigo” doesn’t make the top 5000 at all.

* English “violet” isn’t in the top 5000, but “purple” is synonymous.

* Surprisingly, the kanji the graphic chose for orange, 橙, actually seems to be fairly obscure; it’s not on the newspaper list, and it’s classified as a jinmeiyou (proper names only) kanji. The word 橙色 (*daidaiiro*, “the color orange”) is tagged as a “common word” by Jisho, though… I guess they more commonly write it in kana?

* In the couple of song lyrics I’ve seen that talk about something orange, they just use オレンジ (*orenji*, as in the English word “orange”).

* The normal pattern that linguists have been picking up on recently is that words for warm colors are more common than words for cool colors. (See here, for example: https://theconversation.com/languages-dont-all-have-the-same-number-of-terms-for-colors-scientists-have-a-new-theory-why-84117) Orange seems to break that pattern in both English and Japanese… I guess it’s not all that common for people to need to distinguish something orange from something red or yellow.

Yeah, the common word for orange in Japanese is オレンジ. 橙色 is rare. Same with pink, ピンク is far far more common than 桃色.

Apparently one of the Rages Gau has programmed but can’t get without cheating is the Siegfried Rage. That might or might not had been related to the impostor line he says.

Also here in Spain rainbows have seven colors too. Never thought other countries were different but here we are. You learn something new every day.

I always interpreted the first line in the original SNES release of “Even a child can understand this machine!” as coming out of the “book of secrets” so always thought of it as his journal.

I have a question about the secret password.

There’s a rumor that the Japanese password is a pun that can read “Rest in peace” one way, but “Rot and wither” in another. For instance, here’s an excerpt from the fan translation’s readme:

“One big translation problem I had was with the puzzle in Darryl’s Tomb.

The original puzzle is a curious and very amusing bit that reads “rest in

peace” one way, and essentially says “rot and wither” the other way. ”

However, another FF6 translation comparison says that there’s nothing of the sort (skip to “Rumors that the Japanese version”):

http://kwhazit.ucoz.net/trans/ff6/41falcon.html

Is there a hidden pun, or is it just a baseless rumor?

Complete nonsense. The phrase is a fairly common one as well, it’s not something the FF6 writers invented.

I always thought it was bizarre that, in the scene where Celes is trying to nurse Cid back to health, each line he says sounds a little bit more hopeful, until right before he recovers completely, suddenly he says “I feel I’m not going to be around much longer…” Before I really understood that the dialogue was translated from a different language, and when the dialogue didn’t make sense, it was probably because of a mistake in that process, I thought that someone must have put the lines Cid said in the wrong order by accident, so a line that he was intended to say when his health was near its lowest point was said when his health was near its highest point instead (and now that I know more about how these things are typically programmed, I wonder whether or not all the lines Cid says are arranged in order in the game data according to how healthy he is when he says them.) The real issue is definitely just a mistranslation of that one line, though, probably again because of how rushed the localization process for the Super NES release of the game was.

When it comes to the official strategy guide talking about Celes attempting suicide, I have to wonder whether that was because the guide was written before the localization process was finished, so they weren’t working off the final revision of the English script. Maybe it’s like how the official strategy guide for EarthBound had screenshots showing things like Ness being naked in Magicant, and Threed being called “Threek”, which were changed in the final release of the game.

The thing that sticks out to me about Siegfried in the Coliseum is that, in the original Japanese, he switches to just using 「オレ」 instead of 「オレ様」. That seems like the kind of thing that could have been done to indicate he was a different person from the Siegfried you saw on the Phantom Train, but the nuance of it could easily be lost in translation. (Maybe the fake Siegfried idolizes the real one so much that, even when he’s pretending to be him, it simply doesn’t occur to him not to refer to “Siegfried” using 「様」?) I’m also unreasonably disappointed that nobody uses “Siegfraud” as a fan nickname for the fake Siegfried.

For obvious reasons, the first Final Fantasy games I played as a kid, and the ones that made the biggest impressions on me, were 4 and 6, and I always thought one of the best things about them was the way that, partway through, you got to explore a completely new world, with the underground world and the moon in 4, and the World of Ruin in 6. I thought of that as being one of the defining features that makes a Final Fantasy game what it is, which is why, to this day, it actually seems weird and disappointing to me that, after having that feature in four games in a row (with FF3 revealing that what initially appeared to be the entire world map was really just one landmass being levitated in the air by magic and you had to bring the rest of the world up from under the ocean, and FF5 having you travel through Butz’ world, Galuf’s world, and the combined world,) the developers never really did anything like it again. I still think that Hironobu Sakaguchi must have thought of that idea as being a central part of what Final Fantasy games were about for several years, simply because it was a central part of the designs he created for so long (he also did design work on Chrono Trigger, where the alternate worlds became different time periods and the entire plot was about the connections between them,) but I suppose he probably decided at some point that he’d exhausted everything that could be done with it.

Final Fantasy 9 plays with the concept; the player never gets to explore much of Terra (or Pandemonium), but they are eventually revealed and visited. Still, though, I get what you’re saying; I was *super* excited when I got to the “future” in Final Fantasy 15, got that chilling “World of Ruin” popup, and made landfall in the desolated Galdin Quay. Then… was really annoyed that it ramped me directly into the endgame and didn’t let me roam around the new world.

While it’s not exactly the same thing, there are instances of how the addition of new and better transportation allows for a “world transformation” in games where the world does not LITERALLY transform. FF9’s Mist Continent is the best example of this, I think. When you start the game, you assume the Mist Continent is the whole world, then you find out there’s MUCH more out there, to the point that the Mist Continent almost feels like a different place when you go back. FF1 does something similar when you first escape the inner sea of the southern continent. Actually, this notion of a “much larger world” is something that helped me appreciate something Cid says in FF9. When Cid first gives Zidane the World Map, Zidane doesn’t think much of it. But Cid insists that it is an incredibly valuable treasure. Seeing as I grew up in an era when the world was basically completely mapped, I didn’t think much of it at first either, but if you think of it from the perspective of a culture that is so insular that it has FORGOTTEN that there are other continents, that would be a very valuable artifact indeed.

So, in summary, while I agree that getting to go to a completely new map is fun, I think they still do a decent job of creating “other worlds” (Distant Worlds?) even if not literally.

I’m super interested in the fact that Google translated 「ともよやすらかに」(or possibly the scrambled version?) as “boniously,” because as far as I can tell, that’s not a word. When you google it, the only results are 1) someone’s Instagram username and 2) some Google Books results from older texts, but, upon further inspection, all these results are OCR (PDF to text software, used for automatically extracting text from image files, especially older documents) mistakes, which are supposed to be “laboriously” and “ceremoniously” respectively. That Google would translate anything as such a rarely-seen, erroneous item is really interesting to me… makes me wonder what all goes into Google’s translation algorithms.

For what it’s worth, it’s currently translating the phrase 「ともよ やすらかに」 as “Bimbly” rather than “Boniously.” I guess the algorithm is continuously improving itself?

If I hover over the term “Bimbly” in the result, it shows 「くちばし」 as the source phrase it’s deriving that translation from, if I’m understanding the information it’s giving me correctly. I have no idea what くちばし has to do with ともよ やすらかに. (As far as Jisho knows, くちばし is probably 嘴, meaning “beak”? I guess it starts with the same letter as “bimbly”…)

That is super interesting! I tried it myself and the other thing that came up is “Tomoyo peacefully” or “Tomoyo平和的に” which is more coherent but not great. Not sure why it chose to put some of it in romaji and some of it in kanji/kana. “Bimbly” at least shows up in more results than “boniously,” and it does at least have a definition on Urban Dictionary, so that seems an improvement, though I’m not sure what it has to do with beaks….. fascinating

I mean, Google translated something as ‘Sombatservation’ in the Funky Fantasy IV playthrough, so…yeah, Google just kinda makes up words sometimes…

I don’t think Mato ever figured out why the heck that happened.

Yeah, the “sombatservation” incident was what that reminded me of as well. I actually have a theory about what was going on when Google Translate did that. I have no idea how likely it is, but here it is:

The current version of Google Translate is supposed to work by calculating statistics on both words and sentences that correspond with each other in text written in different languages, and for each word in the source text, it makes predictions about both what that word is likely to be translated as and what context it appears to be inheriting from the sentence it’s used in. In theory, this should allow it to correctly translate words that can be used in multiple senses, like 「出す」 which, depending on the context it’s used in, might be translated as “take out”, “turn in”, “reveal”, “begin”, or even more possibilities.

In fact, by a coincidence that was really nothing short of miraculous, the first version of Google Translate that tried to use statistics on the contexts words are used in went live right when Mato was in the middle of doing the Funky Fantasy IV project, which meant that he was able to compare the results coming from the earlier versions and the later versions of Google’s translation engine. (The earlier version sounded like the stereotypical kind of writing that most people would probably think of when they think of bad translations, which is roughly what you might end up with if you just went through the original text and wrote down the first translation listed for each word in a Japanese-to-English dictionary; it often had laughably bad grammar or misunderstood which sense of a word was being used, but in general, there would be a clear connection between the words used in the original text and in the translation. The later version almost always produced grammatically correct sentences, but those sentences had a much greater propensity to incorporate words that clearly weren’t in the source text and had no apparent reason for being there.)

So suppose you had a neural network engine like the one Google Translate uses, and you trained it using a corpus that included these translations:

水文学 = hydrology

化石学 = paleontology

人類学 = anthropology

Now one important concept that’s common to all languages is having morphemes that can be affixed to many different words in order to alter their meanings in similar ways. And Japanese kanji compounds are a very similar phenomenon, because so many kanji can either be used by themselves to signify a simple concept, or combined with other kanji to convey a more complex concept that’s related to the simple concept in some way. So your neural network might start to notice correlations: some compounds that share the same kanji translate as English words that share similar etymologies.

学 = “ology” (Actual meaning is “study”, “learning”, or “school”)

水文 = “hydro” (Actual meaning is “writing about water”, sort of*)

化石 = “paleonto” (Actual meaning is “fossil”)

人類 = “anthropo” (Actual meaning is “humanity”)

So now, not only is your neural network able to spit out the dictionary definitions of these words, it even seems to be correctly drawing connections between the etymologies of words and how words are related to each other! “Hydrology” really does mean the study of natural phenomena involving water, “paleontology” really does mean the study of fossils, and “anthropology” really does mean the study of humanity.

What might happen, though, if it encounters those fragments of words in contexts where it doesn’t know to expect it might see them?

Suppose your neural network is trying to translate the word 「文化人」, which could be literally interpreted as “culture person”, but what it really means is a public figure that’s active in some sort of intellectual field, like authors, artists, and actors (in fact, “intellectual” would probably be a good translation for it.) Suppose the sentence we’re throwing at your translation engine is 「アリスさんは文化人です」 (Alice is an intellectual.) Well, on second thought, this 「文化人」 doesn’t look so tough, really. I mean, we already know what words all of those kanji are part of. It’s just the second half of 「水文」, the first half of 「化石」, and the first half of 「人類」. So logically, all we have to do to translate this word is to put together the second half of “hydro”, the first half of “paleonto”, and the first half of “anthropo”!

And so, beaming with pride, it presents the fruit of its labors: “Alice is a dropaleanth.”

So that’s my crackpot theory about how “sombatservation” happened. I suspect that Google Translate was trying to make connections between morphemes that make up parts of words in English and words in Japanese, but some of the connections it made were between morphemes that didn’t really share the same meanings, which led to it choosing the wrong morphemes to put together and ending up with a translation that sounded vaguely like something that might be a word in English, and that in fact contained morphemes that exist in real English words, but was just nonsense.

Like maybe it might have tried to mark certain combinations of kana as the Japanese translations of what “somber” would be without the suffix “er”, what “battery” would be without the suffix “ery”, and what “preservation” would be without the prefix “pre” (even though those words are not normally understood as having those affixes, and it’s only coincidental that they’re spelled the same way as if they did,) so when it saw all of those combinations of kana together, it saw that as being a compound word that could be translated as “somb-batt-servation”. (I’m not saying it would have to be trying to use those specific words in a translation, just that I think a process like this might have been what led to it coming up with “sombatservation”. And I don’t actually have any knowledge of the design or programming of the engine Google Translate uses that would allow me to objectively assess how plausible this theory is.)

Still, I have to say that 「ともよ やすらかに」 doesn’t seem to me like a phrase that’s complicated enough that you’d expect it to drive a machine translator off the rails that badly. 「とも」 and 「やすらか」 are just ordinary words that, in that phrase, are being used the way they’re normally used. (It isn’t a phrase like “to pass out” where the word “pass” is used in an idiosyncratic sense that only ever really appears in that one phrase.) It does use 「に」 in the sense of “may this happen”, which is uncommon enough that I could believe a machine translator would stumble on it, but Google Translate isn’t just misinterpreting the intent of 「に」, it’s completely failing to come up with words that are anywhere even close to either 「とも」 or 「やすらか」.

* Actually, I lied when I said that 「水文」 meant “writing about water”; as far as I can tell, that combination of kanji only seems to be used as part of 「水文学」. However, 「水文学」 really does mean “hydrology”, 「水」 really does mean “water”, and 「文」 is a kanji that, in most contexts, describes written characters and literature. I wanted to have three examples of words in the form “XX学” that could be translated as English words ending in “ology”, where each “XX” was also a real word by itself, and three of the Xs could be used to write a word that was unrelated to any of the original three words, but this was as close as I was able to get. Sorry, everyone, I’m just a stupid cat.

The Celes suicide scene rewrite didn’t fool anyone. Who would imagine jumping from a cliff into the ocean would “perk you right up”? That’s not like jumping from a diving board into a swimming pool or even leaping from a tire swing above a lake to refresh yourself. Plus the sad music playing and Celes’s tears basically spelled it out for you; Cid died and Celes felt there was no reason to go on. She planned on ending her life right then and there.

I could be wrong, but apparently the cover-up was so transparent that some first-time players thought that Cid was being morbidly sarcastic.

Count me among them. I wrote about this in another comment on this page. Even back then I got the impression that the scene was rewritten to the minimum extent to pass censorship tests and that Cid was speaking in a passive-aggressive pseudo-fourth wall breaking manner.

Yeah basically. It was pretty obvious and I’d be willing to bet that Woosley knew that people would read it that way.

It definitely came across to me as unusually dark humor!

I was actually about to reply with the same observation until I noticed your comments. When I was young, I always thought that Cid *was* talking overtly about suicide in his “Perk them right up” line – I thought it was just his attempt at some gallows humor. I’d be curious to know if Ted Woolsey was ever asked about this line in particular – I’d love to know what he has to say about it.

You know, as a kid playing the title in the mid 90s, I thought that might have been the case, that I was imagining Cid mentioning the line in a snide or sarcastic tone of voice (like he’s saying “You don’t like living here? Fine, just take a jump off this cliff, I’m sure that’ll change your mind!”), but I honestly wasn’t sure at the time.

It never even occurred to me until now that the SNES translation could be trying to convey anything other than Celes attempting to commit suicide. Even as a kid and even with the censored version, it was completely obvious what was happening (I think I took “perk up” for a grim euphemism / gallows humor, especially since it’s glaringly obvious that all those people are dead.)

I always assumed Siegfried was talking about Ziegfried as being the imposter, which made a lot of sense to me as to why there were two different names. I just assumed there was another lookalike named Ziegfried that was impersonating him and stealing treasure.

I can’t help but feel like Siegfried is a reference to Gilgamesh from FFV. He has a lot of similar character traits.

Regarding the alias “Jeff” — there’s room for speculation, based on the (mostly?) non-canon “Figaro no Kekkon” by Soraya Saga, that this name came from a Knight that Edgar greatly admired when he was younger. (Among other things. There’s some really interesting potential backstory laid out for both Edgar and Sabin that was included in the game.)

https://www.cavesofnarshe.com/forums/ipb/index.php?showtopic=10914&st=0&#entry175391

The Japanese GBA script is different? Welp, guess you’ve gotta re-do the whole project with 6 scripts now 😛

As for the whole Siegfried/Ziegfried, do you recall when each of these was used? I’m wondering if the imposter is always referred to with the ‘Z’ and that was something Woolsey threw in to I guess make it a little more obvious that it was a fake? (Or at least, which he assumed was the fake, if the Japanese version literally refers to them the same)

I think you’re reading a bit too much into a translation that was admittedly very rushed, and which had other name spelling inconsistencies like “Daryl”/”Darill” in it anyway. Sometimes an inconsistency is just an inconsistency.

Oh, I’m well aware. It was more just bringing up a possibility rather than giving the most likely explanation.

No, unfortunately it’s totally inconsistent. The first time he shows up on the ghost train, he’s referred to as “Siegfried”, “Ziegfried”, and “Sigfried” all in the same scene.

It never ceases to amaze me that for all the big talking and self-important pretentiousness that the fan-translation community has about themselves, they often put out such surprisingly and needlessly terrible work.

It’s like their egos are so massive and so gigantic that they can’t resist heavily altering just about any original work to get many things wrong, make half-assed guesses about everything, screw the pooch on basic context, try to skew a work towards their own opinions, ethics or politicking, insert themselves all over it, or need to have in-game characters break the fourth wall to insert their own paranoid speeches about “their” work being “sold”. Pretty much everything that the fan-translation community often gets on such a self-important “we’re-better-than-the-official-translations” kick about, but much worse in some ways.

It doesn’t help that the insular fan-translation community itself is such a tangled mess of a glad-handing, elitist hugbox who whine about the Ted Woolseys, the Working Designs and the Marcus Lindblom’s of the day and proceed to make many of the same or even worse mistakes as the people they hate, unintentionally or even INtentionally, and just really don’t care about shoving their amateur hour, poorly written bastardizations into the wild and crowing on forums and their own websites about how great they are.

And this isn’t just a problem with old translations like FF5 and FF6, they’re still doing a lot of this very recently, like opening the SNES game Princess Minerva with actual in-game characters making a self-important, defensive, butt-clinching spiel against reproduction carts, or inserting political ideologies and pro-Trump lines in other games. Both of which are things committed by people working for Dynamic Designs, which are way more jarring, out of place and uncalled for than even the infamous “William Shatner” line in FF5.

Personally, I just really can’t stand the general self-congratulatory and grand-standing nature of fan-translators in a nutshell. I generally WANT to respect their work when it comes to being able to play a previously Japanese game in English and be able to actually get through the game, but a lot of the work many of these people do are just flat out of poor quality, plastered with unprofessionalism and unable to resist tagging video games with their own self-importance like a graffiti artist tagging the side of a shop or building that belongs to someone else. Even to the point where it leads to things like that “Anti-Earthbound Earthbound Hack” not too long ago.

The fan-translation community would be about 60% better if they could just learn to get over themselves. And 40% better on top of that if they actually knew how proper localization or translation from Japanese actually worked before they inserted themselves into projects like these or formed these Echo Chamber “Translation Groups” of theirs.

And honestly that’s why I have always come to at the very least greatly respect Tomato, his work like the Mother 3 translation and this wonderful blog/site. He’s a much higher cut above many of the people you find at Romhacking.net. It’s just the more I experience myself about the fan-translating community and the more I read his articles like these, especially when they touch on shoddy fan-translations like Sky Render’s, it makes me feel a bit better about this scene, even if this fan-translation scene and the community’s many problematic elements really still does need a LOT of reformation and change overall. It at least gives me hope that things CAN be better.

By FFV, do you mean FFIV? The Shatner line was in J2E’s FFIV translation. I never hear anything one way or the other regarding RPGe’s FFV translation. It’s been a long time since I played it, but I don’t recall the pop culture references or other kinds of fan translation tropes that stick out.

I don’t remember anything glaring about it either. It seemed to get the job done.

It was the first version I played, before the GBA port came out (I didn’t have a PlayStation so luckily I never had to suffer through that version). Aside from “Butz”, my main recollection is that there were a few untranslated Japanese words like “hiryuu” and “suppin”.

A FF5 translation comparison would be very strange, considering how weird the PSX translation is and how heavily punched-up the GBA one is. The FF6 translations are much more similar.

When translating the game there were debates as what to call things. One of them was “Time Mage/Magic” (時魔道士). The class/skillset hadn’t yet been localized in any other title so there was debate whether to call it “Time”, “Dimension”, or more exotic, impractical things that read more like annotations than descriptions. RPGe went with “Time”, probably because it was the only thing that actually fit. I actually thought this was left untranslated until I looked it up. Maybe it was in a beta version.

At the time there was a weird sentiment among a portion of the fan base that basically demanded words, nouns especially, be untranslated in the translation, a bunch of romanji, essentially. Some of those as-is words may have been bowing to community pressure and/or the sentiment existed within the translation group itself. Of course, it could also be indecision, confusion, deadline pressure, or other factors.

I couldn’t find it, but one of the earliest English FAQs of the game devoted a large portion of its text denigrating RPGe’s efforts and the very concept of localization. From what I recall, not only did the English guide basically expect you to understand Japanese, you’d have to set up Shift-JIS encoding to actually read it, which wasn’t trivial in the mid-90s.

Ah! I knew I missed something. It was TimeMage but !Dimen, a compromise.

Yeah, I remember Time Mage magic being called “Jikuu”. I must have been playing a beta version.

…so basically like the “professional translation community”, then?

Kinda want to know more about those translations you’re talking about so I know where not to tread…

I actually heard about about the World of Ruin through GameFAQs message boards. Same with the Blackjack. I would’ve been 12 around the time of playing FFVI, so 1999 abouts, in the States.

I’m confused by your idea of only having learned five colours of the rainbow, as I’ve only ever learned seven (I’m from Canada, by the way. Not sure if that changes much).

Which ones were left out for you? I assume that “blue” and “indigo” could both just be marked “blue”, but I’m not sure what else you could cut out.

In reference to official localizations referencing fan translations:

In FFXIV, there is a Bartz minion that can be obtained by buying the collector’s edition of the latest expansion. When you open the in-game mail to retrieve it, the message includes the phrase, “no ‘butz’ about it!”

I remember multiple online resources in the 90s stating that the “Book of Secrets” was originally a “marital manual” that would be given to newly-wed couples in the old days in Japan. I have no idea if this was an actual practice, but apparently samurai would carry erotic art with them as a “lucky charm against death” per Wikipedia. I like this as part of Cyan’s rationale for having a book like that in his mountain home.

For what little it’s worth, I read the “perk up” line as an attempt at sarcastic gallows humor about the suicide. “She was the happiest corpse I’ve ever seen” kinda thing.

Agreed. I was surprised to see that people apparently read it as an attempt to completely change the scene – while it dances around directly naming the concept, I always thought that the phrasing came off as sarcastic, gallows humor (especially since Cid believes he’s not long for the world and he’s trying to soften the blow for the newly-awake Celes).

It doesn’t help that Celes’ attempted suicide has some great accidental comedy in it (and I say this as someone who has attempted suicide more than once): she hurls herself off a high cliff, somehow misses the rocks, hits the beach, *bounces*, and is *perfectly fine*, apparently because as an augmented Magitek Knight she’s just that badass. But it also comes off as one more punchline to her: “Couldn’t keep Locke’s trust, couldn’t kill Kefka, couldn’t save anyone on the Blackjack, couldn’t save Cid, CAN’T EVEN KILL MYSELF AUGH.”

Darn, I was replaying, and checking back here for what I was hoping to be a deep dive into Cyan’s samurai poem when he releases the carrier pigeon.

The Falcon was found “in a distant land” in the SNES English script, closer to the earliest-release Japanese script, while this was changed to “in a distant valley” in the GBA script, because of what “a distant land” implies in English and how it’s potentially odd for Setzer to call anyplace on the world map “a distant land” at this point in the game—that would be my guess.

It’s possible to explore the entire “World of Balance”, as it’s generally known in English, before the cataclysm that reshapes the world. That is, the player can explore the entirety of the world in the same state as when Setzer describes his search for Daryl/Darril and the Falcon taking place, or at least very close to that state. The player will know they’ve explored the entire world because the world map wraps around north-south and east-west at the map’s edge.

Also notable: Setzer says “a distant land”, which has different connotations in written English from “a distant town” or even “a distant country”, e.g. “Persia” is a “land” to most English writers, which implies an identifiable area that has persisted for a long while regardless of regional politics and can be expected to persist in the same way, while “Iran” might refer to a considerably more recent “country”. “China” might refer to the millennia-old “land” of China or to the current state situated there, depending on context. In any case, most English writers would not refer to something like a state that no longer exists as “a distant land”.

On to the specifics. How would the player accomplish the vast majority of exploring the entire “World of Balance”? They’d need to use Setzer’s airship, of course, and at a point in the story when the party of PCs is flying around on that airship, meaning that if the player has explored the entire world, there’s a pretty good chance Setzer has “explored” it as well.

Now, it’s fair to assume, as it is with most video-game worlds, that we’re supposed to take what we see as shorthand for a bigger and more populous world, closer to the real world in scope, with tiny towns in place of big cities or regional capitals, and so on.

But since the global politics of the Empire’s war drive a lot of the story in the first half of the game, up to and including an under-the-covers mini-game for prizes when attending supper with the Emperor, it would seem at least a little strange to suggest that the world map of the game is supposed to hand-wave into being entire (and entirely unmentioned) nations that the player cannot visit or observe. It seems more likely we’re supposed to imagine the towns to be bigger cities, and the cities, at the very most, to be shorthand for countries ruled from and named after those cities.

So, when the game gets around to the story of Setzer searching for the Falcon, it will seem a little strange to at least some significant portion of English-language readers that Setzer tells the other characters that he found the crashed Falcon “in a distant land”—for those readers, Setzer would have a name for that “distant land”, because he’d been there, and it’s even possible he’d been there alongside everyone else he’s speaking to at the time!

Imagine that you and a group of three people went on a trip to a land far from your homes. Let’s say it’s known to all of you as Farawayland. Let’s say it happened at a point in history when air travel and even world geography as a field were not well-developed. Now, even in that era, if you were describing some earlier experience in Farawayland to those same people, would you refer to Farawayland as “a distant land”, or call it by the name you all know?

It would be pretty weird of you not to use the place’s name! “I purchased this wall hanging… in a distant land.” “You mean Japan? We all know where Japan is. We all went to Japan a year ago, together! You were there!”

I’m guessing this is why the line was changed because I, myself, found that line kind of awkward back when the game was newly released in the US as FF3. I was an imaginative kid, but I knew I’d explored the entire “World of Balance” map with Setzer’s airship. I’d been to every city and town and plenty more places besides. It was like the game was suggesting that there was some fantasy equivalent to China or Zimbabwe out there in the world of the game that Setzer once visited, but it only existed for the purpose of that one story about searching for his friend.

Even back then, I understood why they didn’t want to say “I found the airship crash south-southeast of Tzen,” or whatever, because it would raise the question “Couldn’t Setzer just sweep the entire world map in a few minutes with his own airship?” and because naming the place like that would be kind of boring, but it still seemed strange to me as an English-language reader. They’d written themselves into a bind with that line, not a major one, but a bind nevertheless, because the reader would still think about that tiny world map and how they’d been everywhere on it.

The GBA script’s “distant valley”, on the other hand, could refer to one of any number of places on the “World of Balance” map, and more importantly, the “distant valley” could be assumed to exist e.g. somewhere in the midst of a blob of mountains on the world map, so that the player and the PCs couldn’t possibly have “visited” it, or know the local name for it, etc.

What I’m curious about, though, is whether the term used in the Japanese script has the same connotations as “a distant land” in English, that is, “someplace you’ve never been that I might as well describe to you in the vaguest possible way”. My Japanese education was far too limited and is far too distant in my past to even begin to figure that one out.

Glancing at the screenshot quickly, the phrase in the Japanese is 「遠くの土地」 /tooku no dochi/. I don’t know much about how to interpret the nuances of /dochi/, but English dictionaries give definitions like “plot of land” or “region,” and the kanji used refer to the literal ground/dirt there rather than any more abstract boundary. It’s certainly not 国 /kuni/, “country,” at least.

Thank you. That’s interesting, because you might indeed say “in a distant region” or the like to describe a crash site even if you and the people you’re addressing had a name for the place in question. It seems to emphasize the distance the Falcon traveled before crashing instead of, say, the mystery of some remote locale.

I love the idea of the ‘Very Slightly Erotic Book’