In this article series, I compare Final Fantasy Adventure’s translation with the original Japanese script. For project details and/or to start from Part 1, see here.

Part 3: Golem Cave to Legendary Sword

This section of the game, from Days 4 and 5 of the live stream, was mostly full of fighting and dungeon exploration. But it did feature a few key story moments too.

I’ve highlighted a few noteworthy translation changes in the article below, but if you’d like to see even more detailed changes, definitely see the videos above.

Dialogue Drops

Previously, we’ve seen how text was condensed down for the English release. It’s not just NPC text though – main story dialogue underwent lots of cuts too.

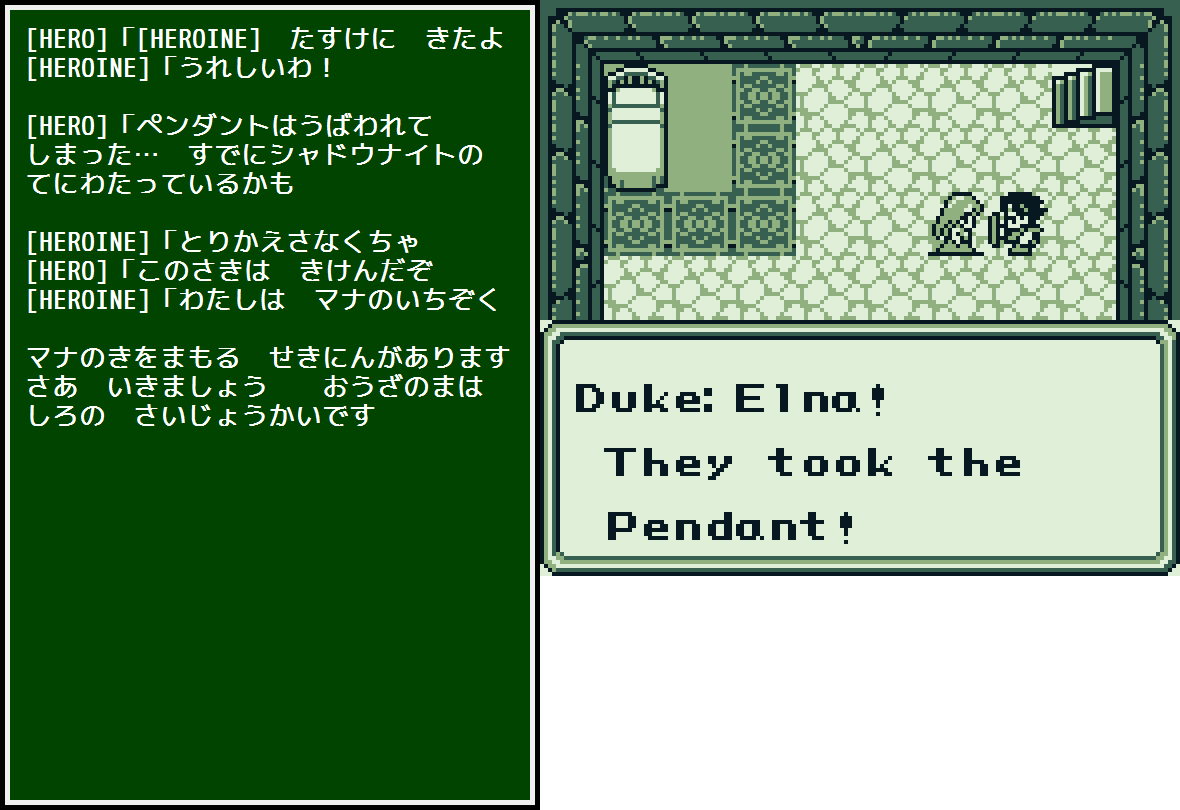

In this example, the hero has just saved the heroine from the bad guys. Here’s how the Japanese and English scripts compare:

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| HERO: HEROINE! I came to save you! | HERO: HEROINE! They took the Pendant! |

| HEROINE: Oh, I’m so happy! | |

| HERO: The pendant was stolen. The Shadow Knight might already have it by now. | |

| HEROINE: We have to get it back! | HEROINE: We have to get it back! |

| HERO: It’s going to be really dangerous, you know. | |

| HEROINE: I’m a member of the Mana Clan. I have a duty to protect the Mana Tree. | |

| Now come on, let’s go. The throne room is on the top floor of the castle. | …… Let’s go! Dark Lord’s room is on the top floor! |

As we can see, in Japanese, the heroine shares some short, yet important and character-defining lines, but these are missing in the English version. The heroine’s motivation is no longer clear in the translation.

A similar example of missing motivation happens shortly after this. The hero, accompanied by the heroine, confronts one of the main villains:

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Shadow Knight: It’s been a while, HERO. It would seem your sword skills have improved a bit. But has it improved it enough to stop me, I wonder? | Dark Lord: Looks like you’ve been a bit stronger. But, not enough to fight me, boy! |

| HERO: Shut up! I’m going to beat you and avenge Willy! | |

| HERO: Stay outside. I’m certain this is going to be the most difficult and dangerous fight so far. | HERO: Stay outside. It will be too dangerous here. |

| HEROINE: All right… | HEROINE: …… Okay…… |

| Be careful. | |

| Shadow Knight: How very admirable. Now then, have at you! | Dark Lord: Good boy, HERO! …… Now, come! |

Willy was a character from the very beginning of the game. He’s also the whole reason the hero is on this quest to begin with. So I was surprised to see this key, emotional line about Willy dropped entirely. At first, I thought maybe it was cut due to text length limitations… but the English version adds a new, unimportant line for the heroine in this scene, along with many extra ellipses.

Anyway, these are just some simple examples of how important scenes in the story were trimmed in the English release. When seen side-by-side, we can see how the English translation is more like a “skeletonized” version of the original script.

Being a Villain

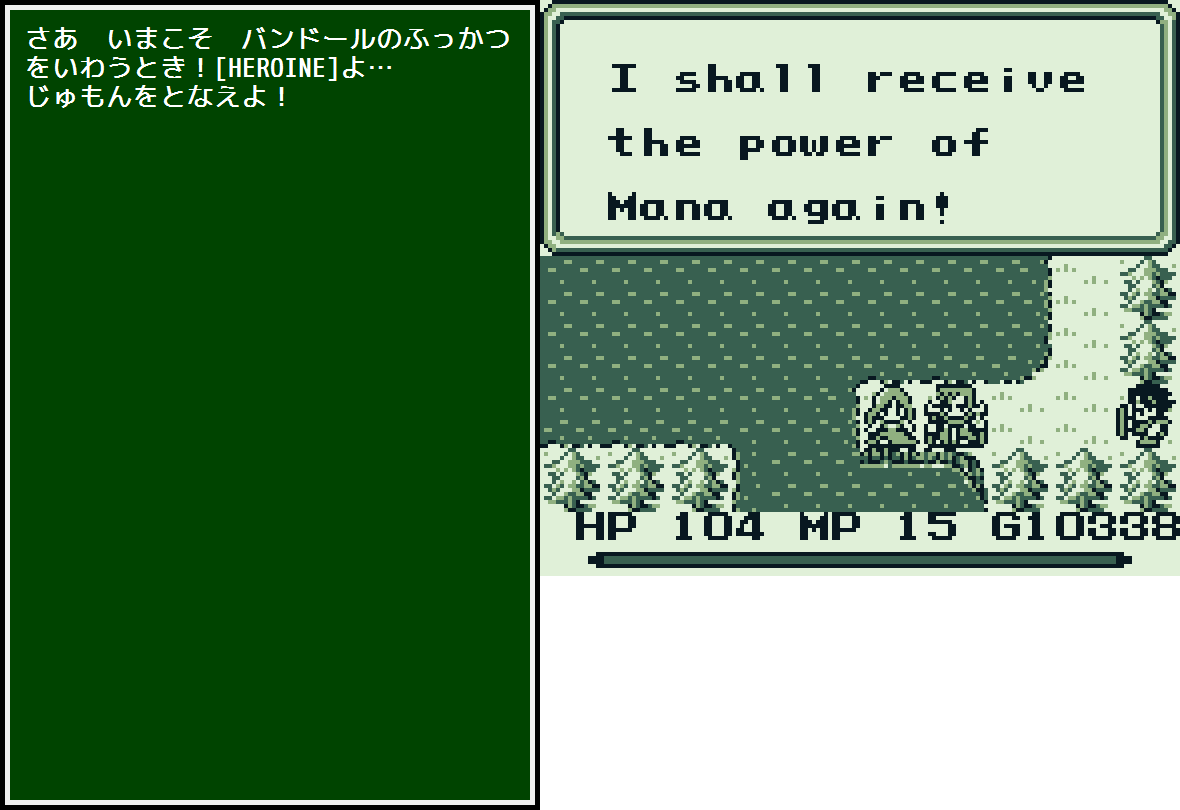

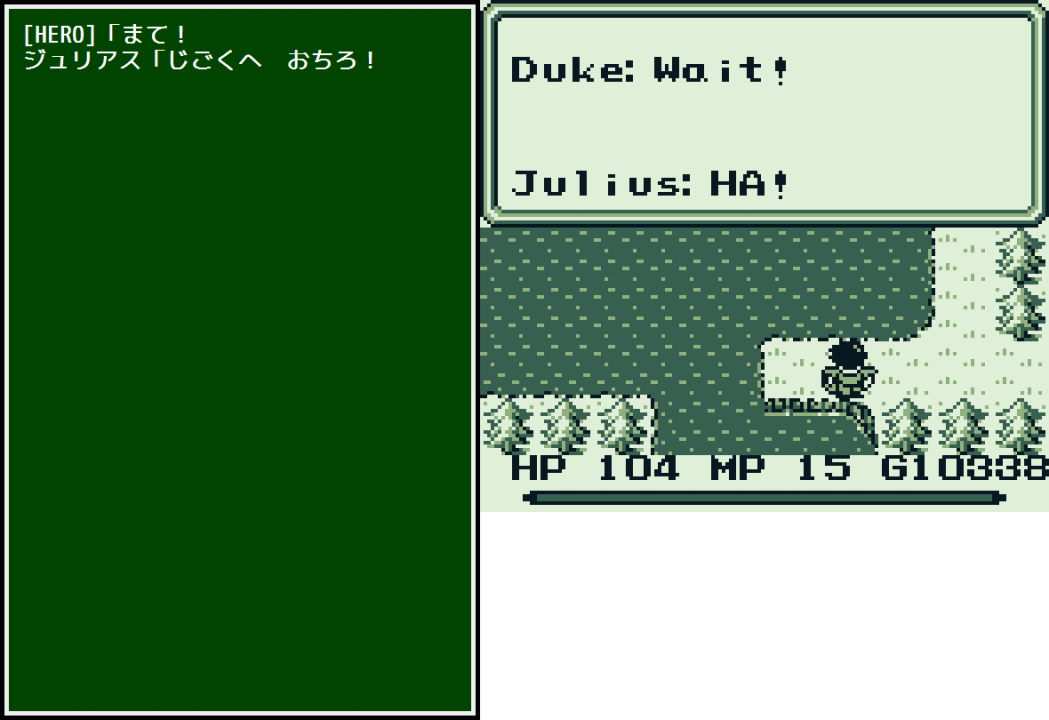

After the Shadow Knight is defeated, the game’s true villain, Julius, abducts the heroine again. When the hero arrives, Julius reveals his secret background and true goal.

Julius’ motivation, as explained here, is slightly different in the Japanese and English scripts:

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Julius: You’re too late, HERO. The power of Mana is now mine. | Julius: It’s too late, HERO. She’s mine…… |

| HERO: Julius! | HERO:What?! |

| Julius: Now, HEROINE. Hold this pendant aloft and chant the spell to make the water rise into the heavens. | Julius: Use this Pendant and cast the spell, HEROINE. |

| HERO: HEROINE! Stop! Come over here! | HERO: HEROINE! Don’t! Come over here! |

| HEROINE: …… ………… | HEROINE: …… ………… |

| HERO: What’s wrong? Julius! What have you done to her?! | HERO: HEROINE? What did you do to her, Julius? |

| Julius: I am a descendant of Vandole, which once obtained the power of Mana, long ago… Controlling one measly little girl is nothing to me. | Julius: I am the last one left of Empire Vandole. |

| Now, then. The time has come to celebrate Vandole’s rebirth! | I shall receive the power of Mana again! |

| HEROINE! Chant the spell! | Now, HEROINE! Reverse the Waterfalls! |

The difference between each individual line above is minor, but when taken as a whole, the Japanese text gives much more information and presents it all more clearly. In the Japanese script, it’s also clear that Julius intends to rebuild the old Vandole Empire. He’s also just “a” descendant in the original script, but this is changed to “the last one left of Empire Vandole” in the English version.

Basically, if you stopped the game at this point and casually asked a Seiken Densetsu player and a Final Fantasy Adventure player what Julius’s goal is, the Japanese player would probably say “rebuild his ancestors’ empire” and the other player would probably say “to get power”.

The Next Dimension

There are some small content changes after Julius’ speech that are in line with other changes so far:

Falling a Lot

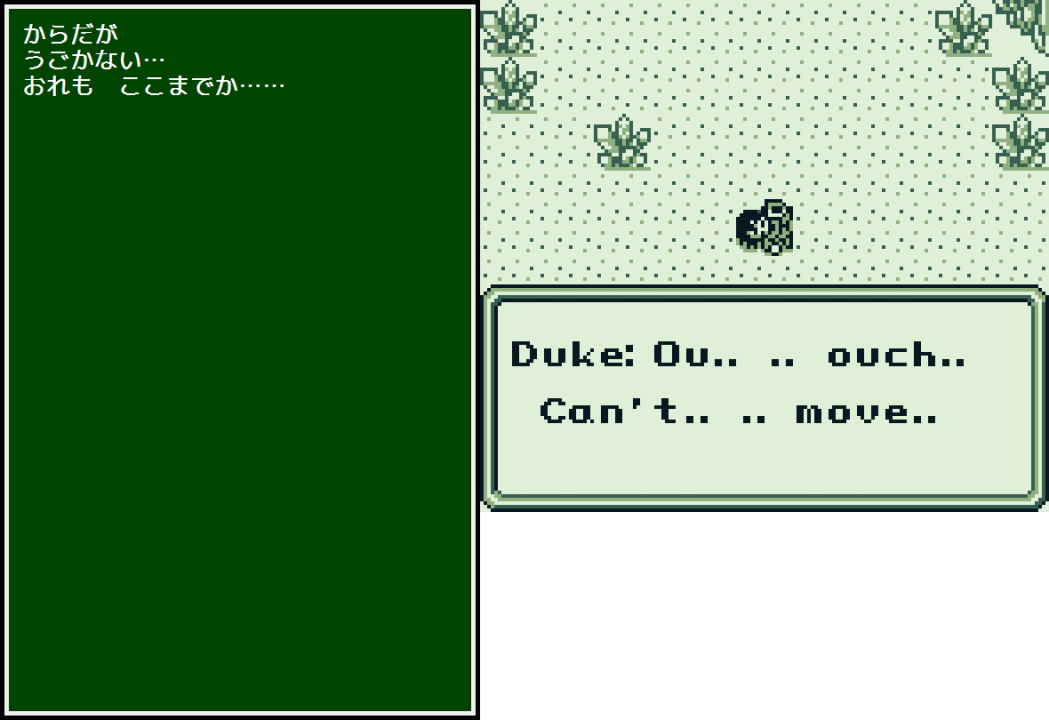

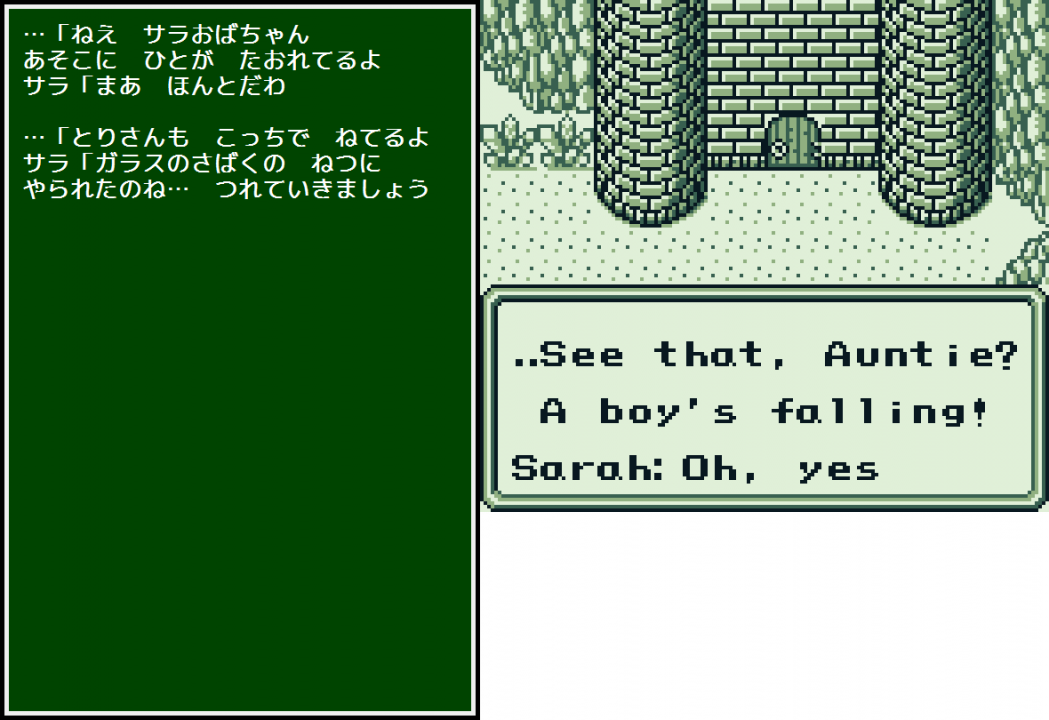

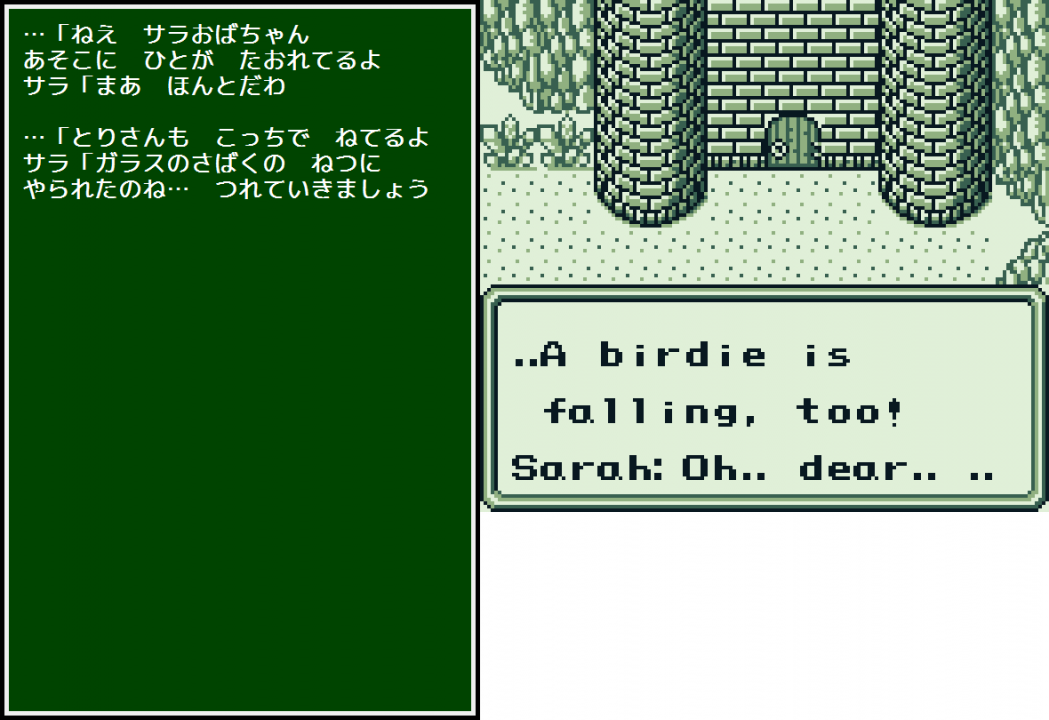

The hero ends up lying in a scorching desert, unable to move. It looks like it’s all over for him, but then a chocobo suddenly shows up and carries him to a nearby town. We then overhear some NPCs talking about the hero and the chocobo, but the English gets kind of weird:

Neither line about falling makes sense in context, and they don’t apply to the situation at all. The problem stems from two common mistakes in Japanese-to-English translation:

- The Japanese word taoreru can mean multiple things depending on the context, including “to fall over”, “to collapse”, and “to be defeated”.

- Japanese verb forms and tenses don’t have perfect, 1-to-1 matches with English verb forms and tenses. When you study Japanese and learn about the simple te + iru verb form, you’ll likely be told it’s it’s like “verb + -ing” in English. It’s not 100% the same, however – in this case, “has collapsed” would’ve been a more appropriate tense and word choice to use.

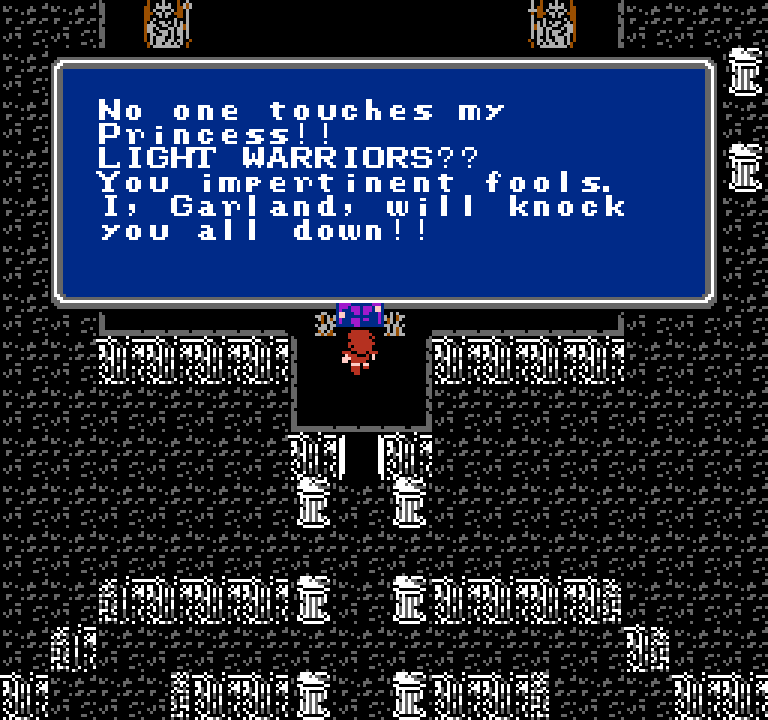

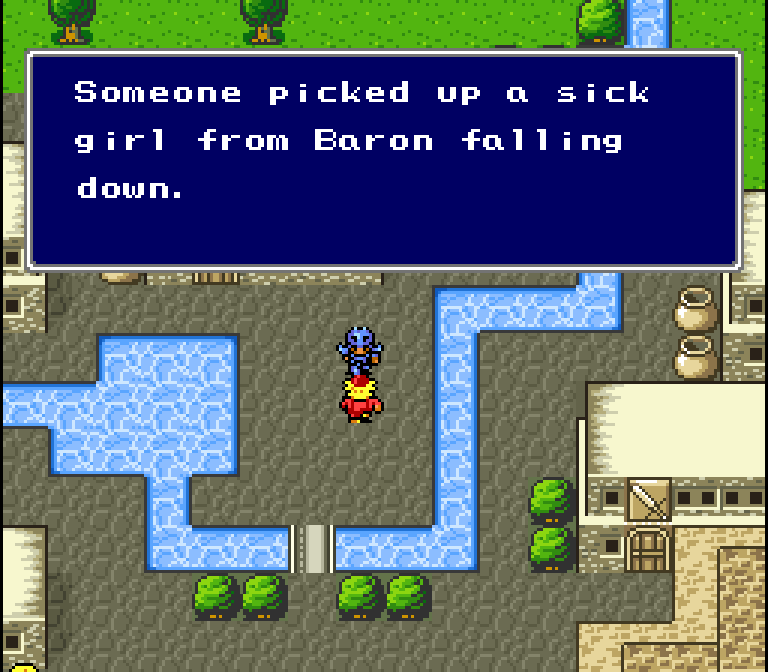

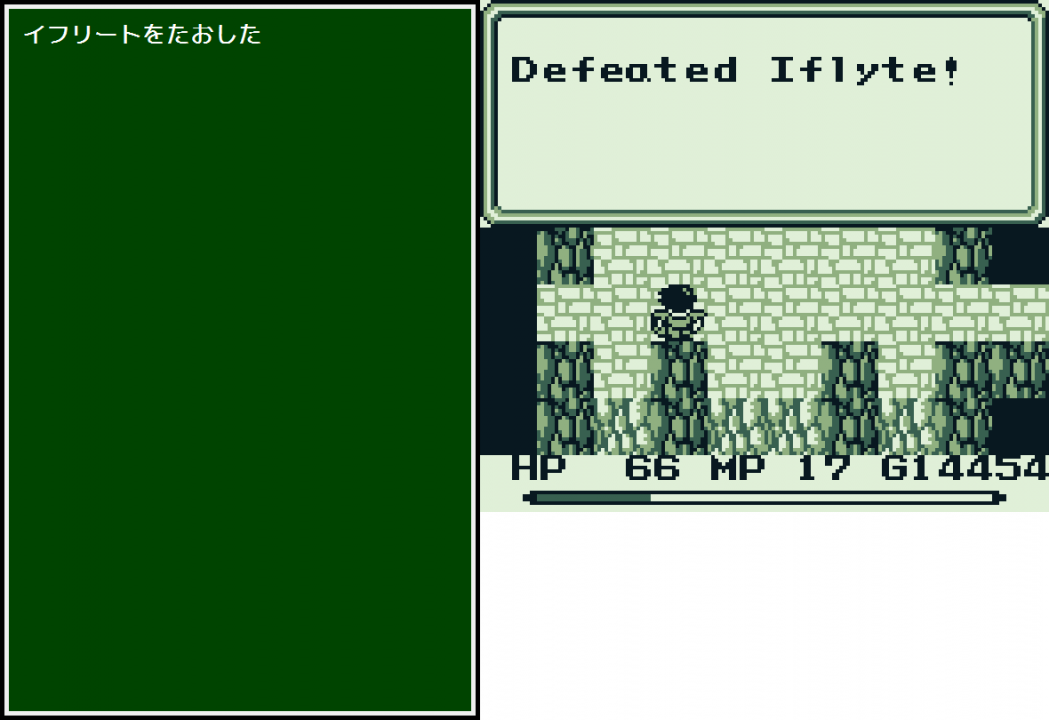

These same problems occurred in other early Final Fantasy translations, in fact:

Questioning the Plot

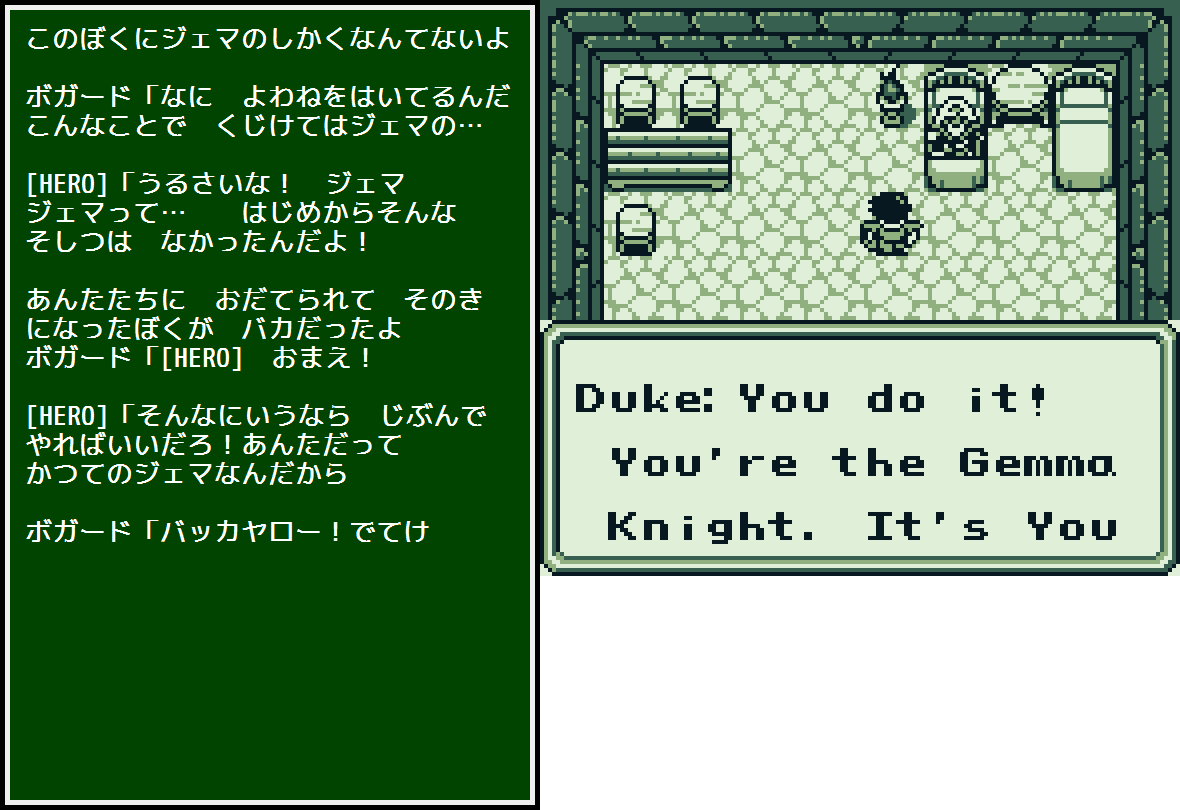

The hero wakes up in a bed. Bogard, an old knight who defeated the evil empire long ago, is there too.

Again, story details and whole sections of dialogue were cut or changed:

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Translation |

| Bogard: HERO! You’re awake! | Bogard: HERO…… |

| HERO: Bogard! You’re alive? | HERO: .. Bogard! How’ve you been? |

| Bogard: I got thrown off the ship back then, and, well… But then Sara, the lady of this house, took me in. | Bogard: I was thrown from the ship…… But Sarah picked me up and saved me. |

| When they brought you in too, I thought all hope was lost. | I’m glad to see you again, HERO. |

| It would be terrible if the Jemas’ last hope died like this. | |

| HERO: I’ve lost all confidence in myself. I let Amanda die… and I couldn’t even protect a single girl… I’m not fit to be a Jema at all. | HERO: I can’t do this anymore.. I can’t do it! I’m not the right one to be the Gemma Knight. |

| Bogard: Quit your whining! Losing heart like this is no way for a Jema to– | Bogard: Come on! You must stand.. |

| HERO: Just shut up! Jema this, Jema that… I was never cut out for it to begin with! I was stupid to fall for your guys’ flattery! | HERO: NO! What’s that Gemma? …… Why me? Why does that have to be me? |

| Bogard: That’s enough, HERO! | Bogard: HERO, you.. |

| HERO: If you’re that insistent, then do it yourself! You used to be a Jema, after all! | HERO: You do it! You’re the Gemma Knight. It’s You! |

| Bogard: You idiot! Get out! | Bogard: .. Shut up! .. GET OUT!!.. |

Overall, the English translation here is messy and has some jumpy logic. The reason for the hero’s sudden attitude change is clearly explained in the original Japanese text, but not in the English script.

I feel like there are a couple factors behind this messiness: the references to death – even the simple “you’re alive?!” line – were dropped, text probably needed to be trimmed for technical reasons, and it feels like this part of the game’s script didn’t get as much post-translation editing work than other parts.

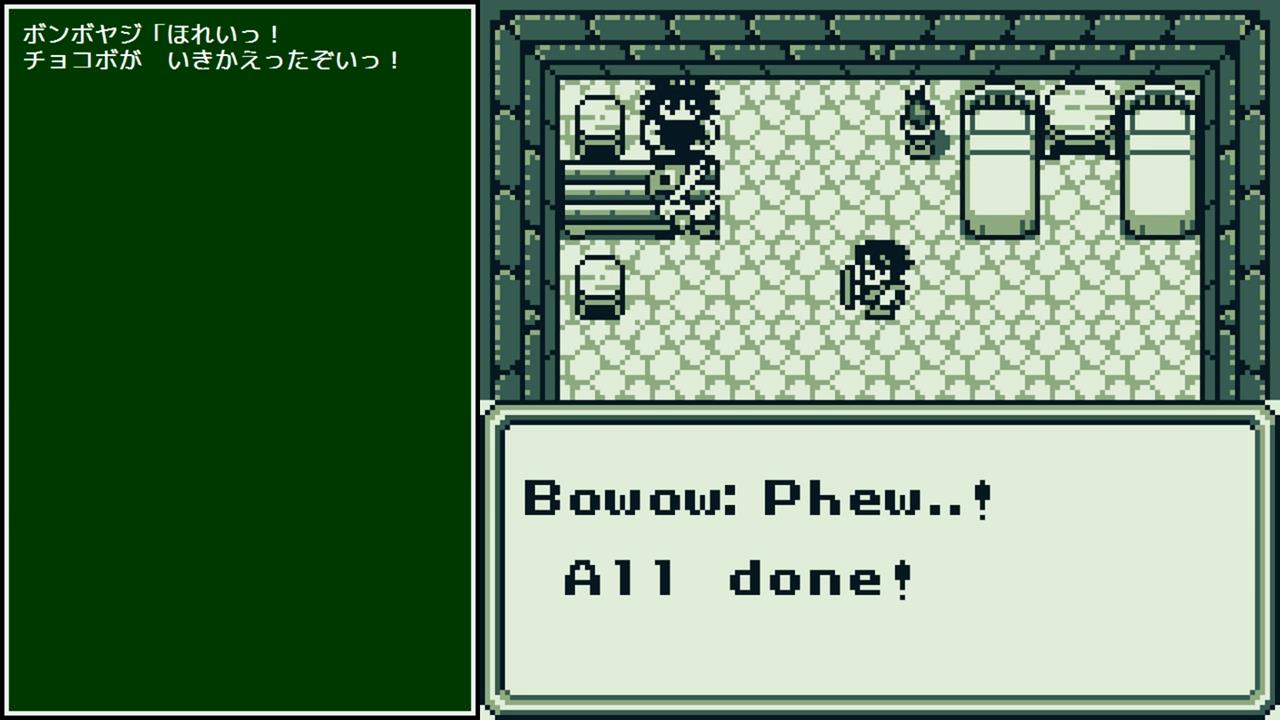

Mad Doctor

A scientist in town replaces the chocobo’s injured legs with robot legs. This allows the chocobo to walk across rivers and oceans. This modified chocobo is basically this game’s version of the Final Fantasy series airship – it opens up the entire world for exploration.

In Japanese, the scientist who performs this transportation upgrade is known as ボンボヤジ (bonboyaji), a spelling variation of the phrase “bon voyage”. The name is fitting too, as “bon voyage” means something like “good voyage” or “good journey” in French.

In the English version of the game, this character was renamed “Dr. Bowow”. I’m not sure why the name was changed or what the new name even means, if anything. Is there a dog joke I’m missing? Is it a reference to those chomping “Bow-Wow” creatures from the Super Mario Bros. games? Something else? Whatever the case, the original transportation connection seems to have been lost.

But wait, the mystery doesn’t stop there! In the Game Boy Advance remake, this important character isn’t named at all, because he doesn’t even exist. And in the 3D remake of the game, the character doesn’t even have a name anymore – he’s simply referred to as “The Professor”:

Basically, it appears this character’s name has never been handled consistently in either Japanese or in English.

Text Swap

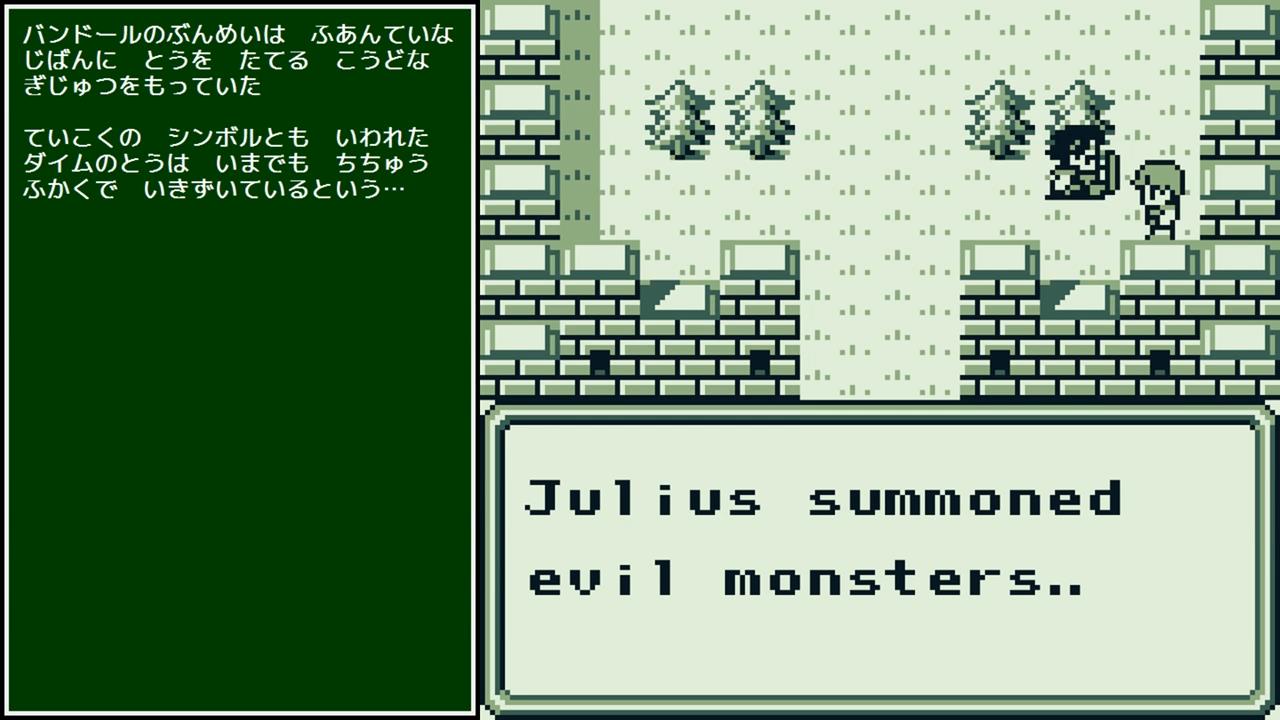

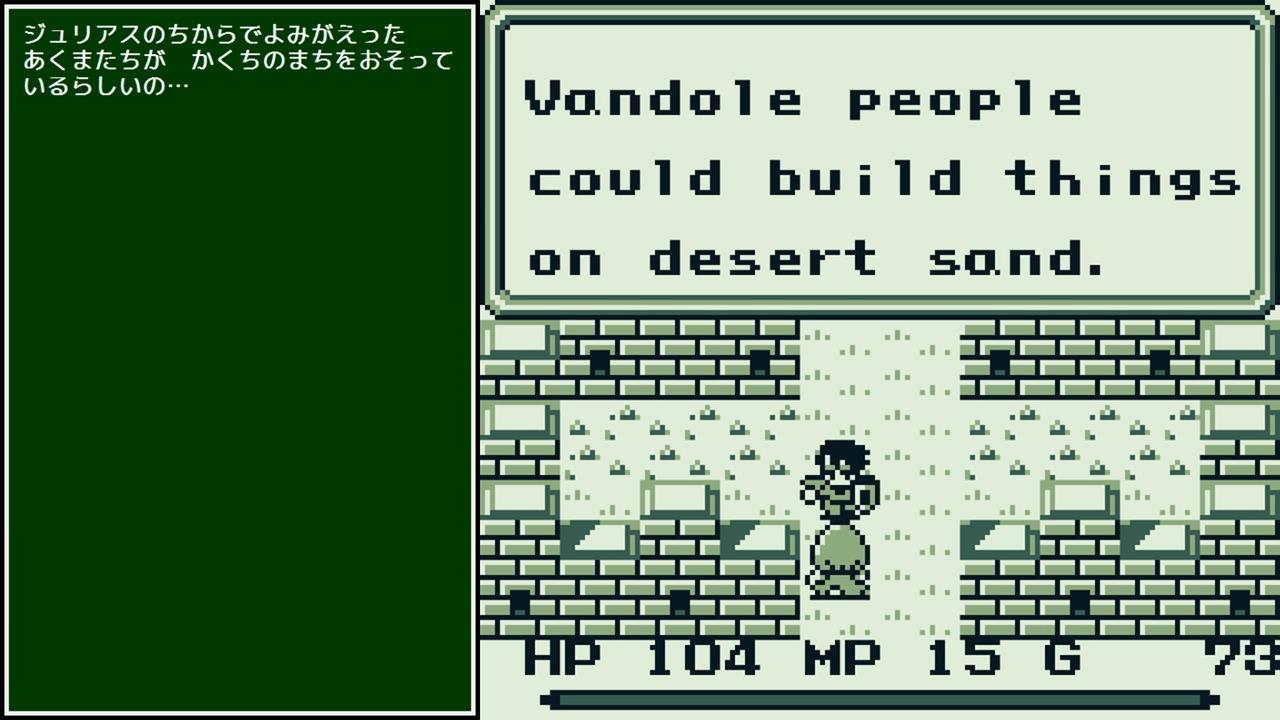

Two characters in town share information about recent events and old historical stuff.

What’s interesting here is that these two lines somehow got swapped during the game’s English translation. Now the girl says the guy’s line, and the guy says the girl’s line. I assume this was the result of a simple text entry mistake, such as someone accidentally entering the translated lines into the wrong spots.

Of course, this isn’t a big deal or anything, but it’s not the first time this has happened in a game’s translation. Here are two other examples that come to mind immediately:

For whatever reason, I find this text swapping phenomenon interesting and always keep an eye out for it. If you’ve noticed it any other translations, let me know!

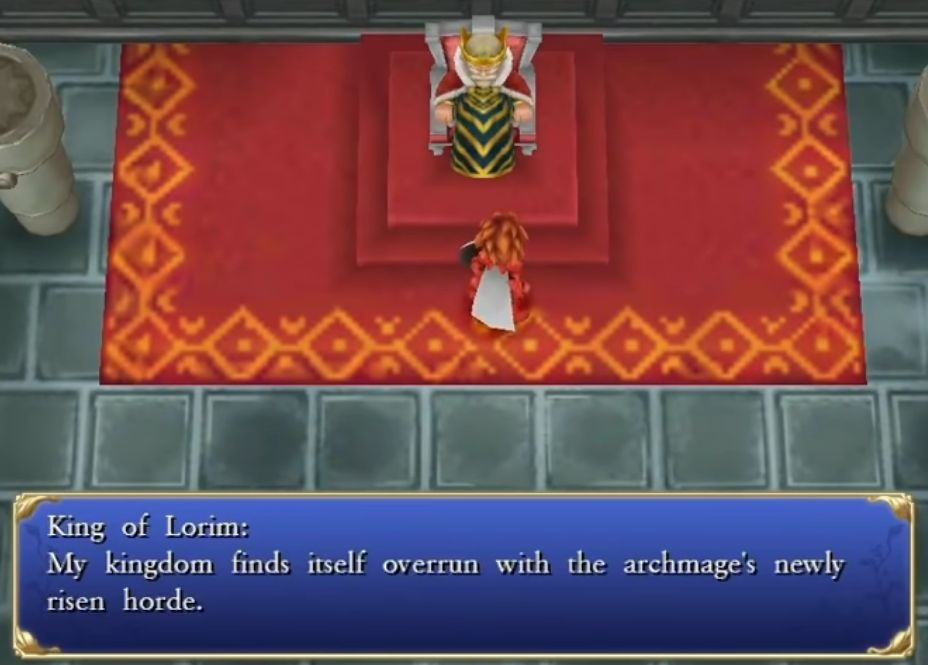

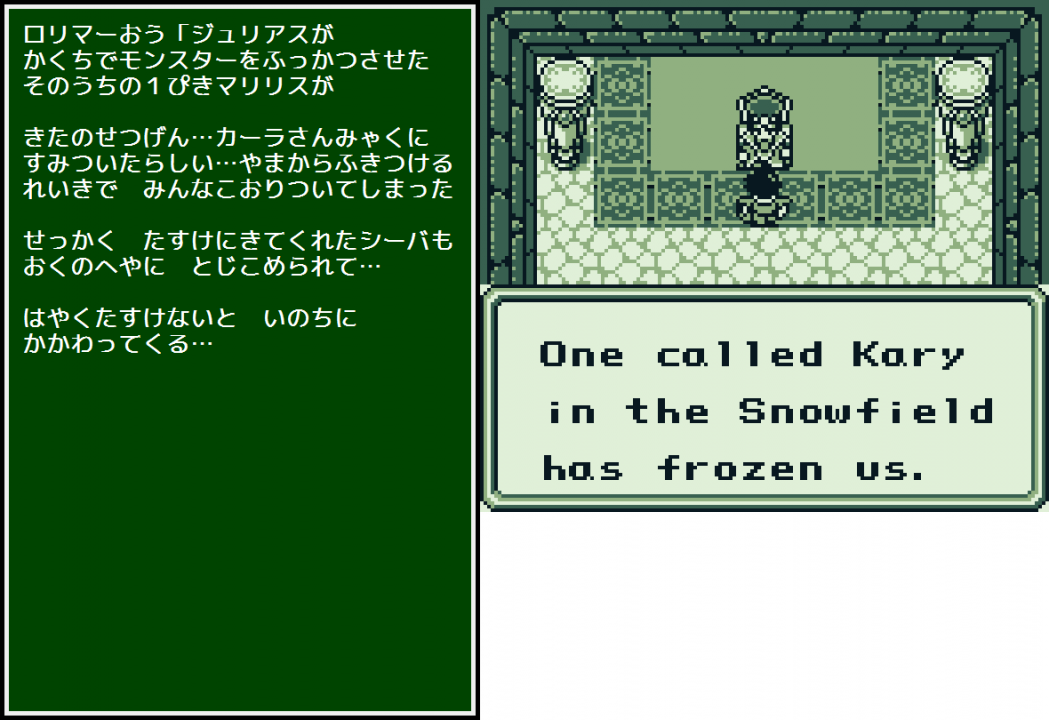

Lorimar Kingdom

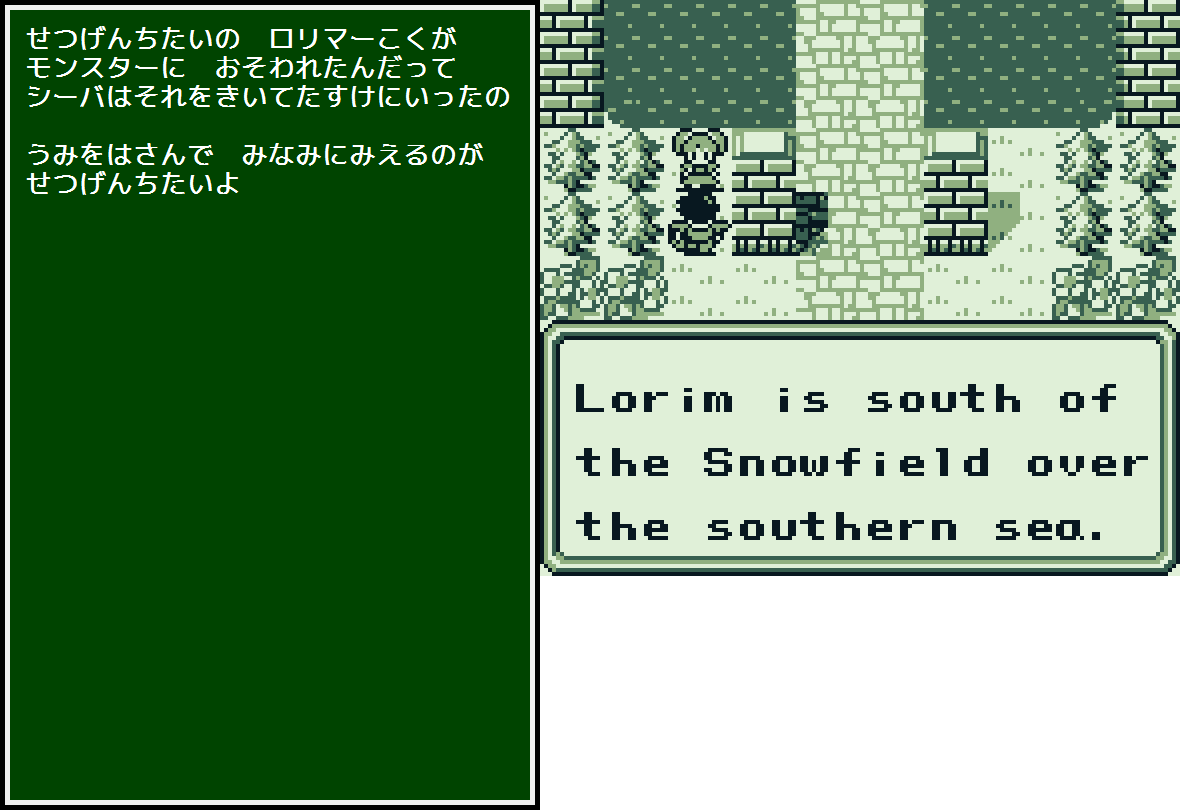

The hero sets off to a distant kingdom that has been frozen by an evil monster. In Japanese, this kingdom is known as ロリマ― (rorimā), which might normally be translated as “Lorimar”. But in the English script, the name was shortened to just “Lorim”:

In the 2003 Game Boy Advance remake, the kingdom’s name was translated fully as “Lorimar”. Strangely, though, the name reverted back to “Lorim” in the translation of the 3D remake released 13 years later:

Incidentally, this kingdom’s name is mentioned briefly in the sequel to Seiken Densetsu/Final Fantasy Adventure:

|  |

| Seiken Densetsu 2 (Super Famicom) | Secret of Mana (Super NES) |

In the sequel, the kingdom still goes by the same name in Japanese, but is called “Lorima” in English. “Lorima” isn’t necessarily wrong, but it suggests that the translator either wasn’t aware of the previous “Lorim” name or didn’t feel bound to it.

Now that I think about it, I wonder how much of Final Fantasy Adventure’s English translation was referenced during sequel’s translation, if at all. That’d be interesting to look into sometime!

Fantasy Ties

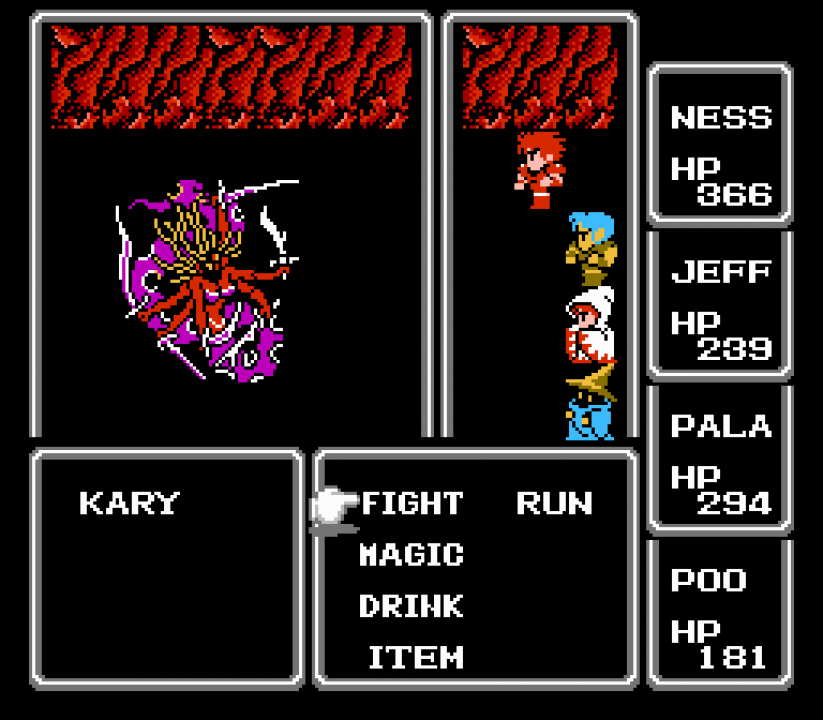

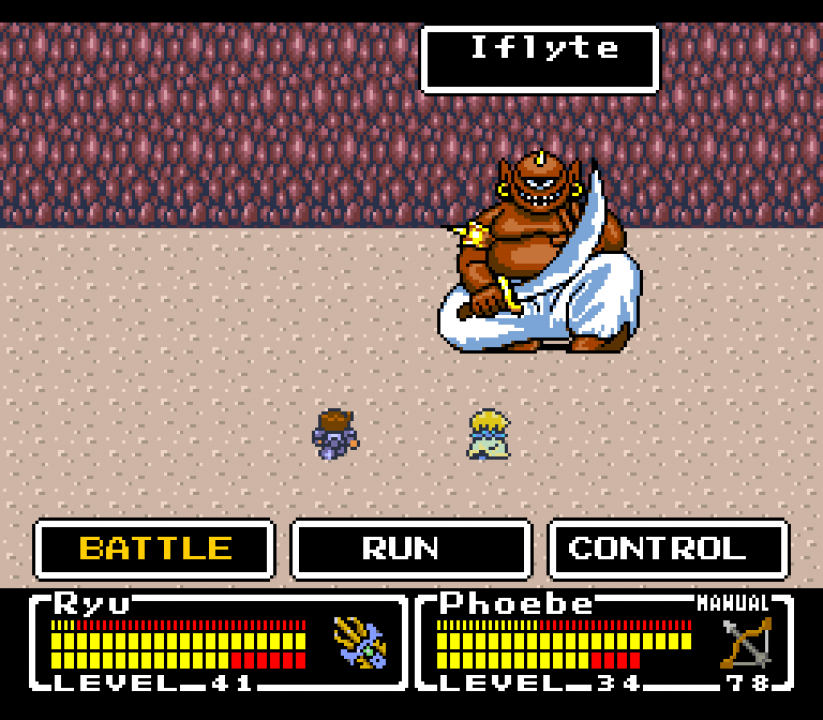

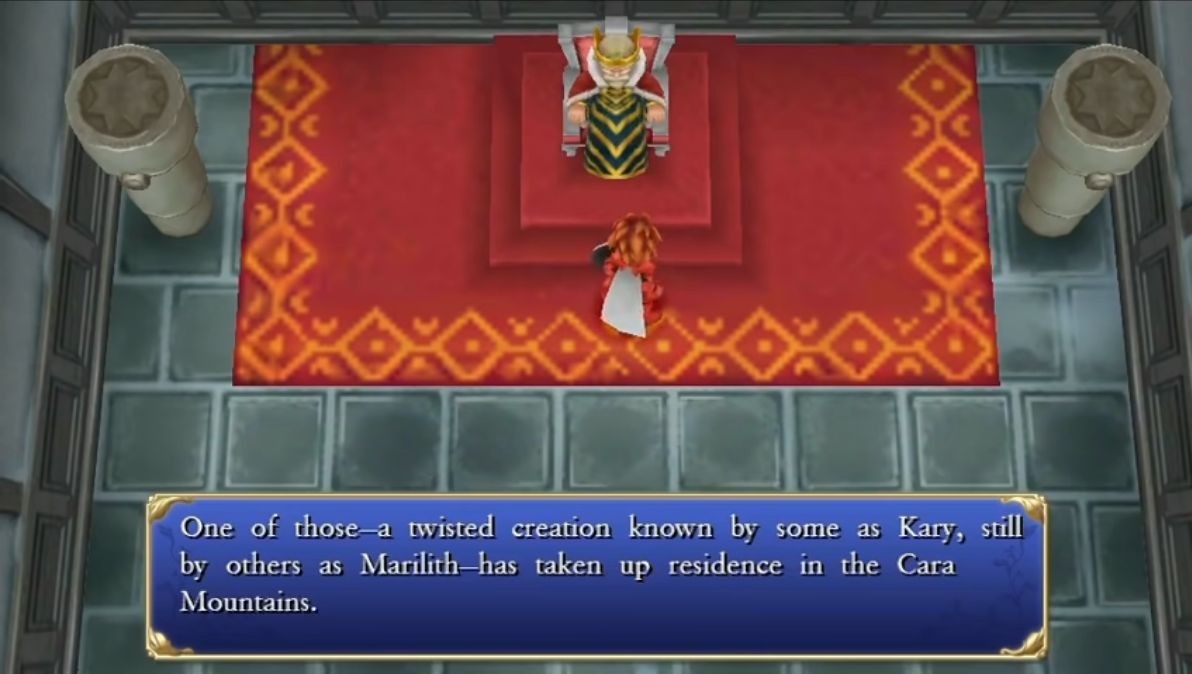

As we’ve already seen, early games in the Final Fantasy series regularly pulled from Dungeons & Dragons, H.P. Lovecraft, and even real-life religions. And since this is an official Final Fantasy spin-off, there are similar references here too. Except these references sometimes changed during the localization process:

Some of these changes might already sound familiar if you played Final Fantasy games in English back in the 1990s:

The Game Boy Advance translation reverts the name back, but spells it “Marilys”, which is technically a valid transcription of the Japanese name. The translation of the 3D remake tries to bridge the name differences by mentioning both names together:

It’s interesting how original translations can continue to affect future translations even after so much time. It reminds me a lot of the original English translation of Final Fantasy IV in that regard.

![press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV] press start to translate [Final Fantasy IV]](https://legendsoflocalization.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/bbenma.png)

Wasn’t “Bon Voyage” also the name of the cannon travel characters in Seiken Densetsu 3, or something?

Yes. Along with Bon Jour and Bon Soir, according to my memory of playing the fan translation.

I’m still wondering where they got Gemma from. My assumption’s always been that it’s gemma as in bud: a bud of the Mana Tree. Checking Jisho for ジェマ only seems to indicate the woman’s name Gemma though, and it’s not otherwise a common English word.

I love the “bonboyaji oyaji” (“bon voyage dude”), but how would you translate that to retain the wordplay?

Later Alligator? lol

Notes:

* A character by the name of Gemma appears in Secret of Mana. In the SNES version, he is named Jema.

* Maralith is also named Maralys in Final Fantasy 9.

* The Dark Knight, Leon’s brainwashed identity in FF2j is also known as the Dark Lord in the FF2 prototype.

Bon Voyage / Dr. Bowow is not in Sword of Mana, no, but because the world can no longer be completely (or at all) traversed on a Chocobo, there are now cannons like in Secret of Mana that fast-travel you all over the world. In that game I *believe* they’re called the Cannon Travel Brothers, but in Sword of Mana it’s… Dr. Bomb. No idea what the Japanese name is there, but I’m half expecting it to be Bon Voyage again. Makes me wonder what the Cannon Travel Brothers are called in Japanese, too!

After encountering Dr. Bomb in Sword of Mana (in the weeks of the FFA live streams), I was immediately struck by the potential to call him Bomb Voyage, which would be the best of both worlds.

A character named Dr. Bomb also appeared in Legend of Mana, for what that’s worth, but he was an entirely different person.

Your last GBA screenshot says “Malyris,” not “Marilys.” So… what now? Ha ha.

In another bit of synchronicity, both are valid transliterations of マリリス

I think it’s painful to see just how mistake-ridden and chopped apart RPG translations were in those times. Not trying to be a jerk or question their career choice here, but I wonder if translators for old games like FFA took their jobs seriously at all. None of this is professional at all and it just reeks of ineptitude.

To my understanding, most of Square’s English translations from around this time period were done in-house in Japan. When you have non-fluent English speakers trying to convey everything that’s present in the original language, while at the same time having to work against screen and cartridge size limitations–especially on the Game Boy (see also SaGa 1, aka Final Fantasy Legend, which got butchered even harder than this game)–something is bound to go wrong.

That’s correct. At the time, most (not all) Square translation work was handled like that up until FFVIII, where things changed.

That on top of the censorship policies at the time as well and the relative difficulty to search up the proper forms of some of the references pre-internet while still on a deadline.

Mato has pointed out examples where there’s evidence of an editor in some places, like in FF4, but that was the exception not the rule. Just look at the This Be Bad Translation series of articles for more modern examples of developers either not having/wanting to use the resources for a good translation, or thinking good enough would be just that.

Especially back then, the company executives had that kind of mindset. Kyoko knows English well enough. They can translate it for a fraction of the cost of a “professional.” Why bother paying more than we have to!

Yeah, in those NES, Game Boy, etc. days, translating games was more of an afterthought for Japanese companies, and if a translation was “good enough” then it was okay. That view changed as the industry matured, although that same view has resurfaced recently in regards to having machine-translated video game text.

The late 80s/early 90s were a really interesting time for Japanese-to-English translations.

As noted, there are many factors as to why a certain work may not receive a faithful adaptation.

Time and budget constraints, not having a professional translator, not being able to do proper research on a word or phrase, or in some cases they simply didn’t care as long as it was ‘good enough’.

And yes, Nintendo in particular had some pretty strict censorship policies. No references to death or sex or religion, among other things.

All I can say it thank god times have changed. Japanese media has become big business in the west and today’s consumers demand well-done translations and adaptations. The internet has also made it much simpler for fans to do their own research, leading to excellent sites such as this one!

Clyde, have you had the opportunity to investigate RetroArch’s “AI Service”, which uses optical character recognition to translate game text on the fly?

I am interested in learning his thoughts on this as well.

I saw the news a while back, plus a video or two of it in action, but haven’t looked into it any deeper. The videos samples were about what I expected & sounded a lot like when someone tried it with Mother 3 back in 2006:

This mixture of technology and translation is right up my alley though, so I really should give it a try sometime, might make for an interesting stream or two even.