When you jump into the world of translation, you quickly realize that one language might have special terms that other languages don’t have. So what do you do when you have to translate one of these tricky words?

In this new article series, I plan to showcase common terms and phrases that appear in Japanese entertainment that don’t have solid equivalents in English. This time, we’ll be looking at the words maō and daimaō. We’ll see what the words mean, why they’re a problem for translators, and how they’ve been handled in games since the 1980s.

What is a Maō and Daimaō?

Again, it’s difficult to explain with a single word in English, but a maō is basically a term for a supreme supernatural being that’s usually super-evil. It’s a generic term that’s extremely common in Japanese fantasy settings.

When you think of a fantasy RPG, you kind of assume it includes a king, a queen, a brave hero, and stuff like that, right? A maō is about on that same level of commonness. In short, if you’re playing a game that’s cliché enough to have a chosen knight or a hero of light, there’s great chance there’s a maō too – and it’s probably the final boss.

A daimaō is pretty much the same thing as a maō – the dai part means “big” or “great”, so it’s an even more powerful / evil version of a maō.

The Problem

In English, we don’t have a solid, universal term for maō and daimaō the way Japanese does. But you can’t just ignore the words when translating, so you have to come up with something. There are at least five main approaches to the problem.

Option #1: Focus on Each Character by Itself

First, right off the bat, the 魔 (ma) presents a big problem. It actually has a bunch of different meanings, including:

- devil, demon, evil spirit

- harmful (or evil) person or thing

- magic

- supernatural

- crazy, insane

- obsessed

So which one are you supposed to choose? It might seem like an easy question at first, but the best choice actually depends on each specific situation. Maybe the maō in one game is demon-themed, while a maō in another is just a magical creature.

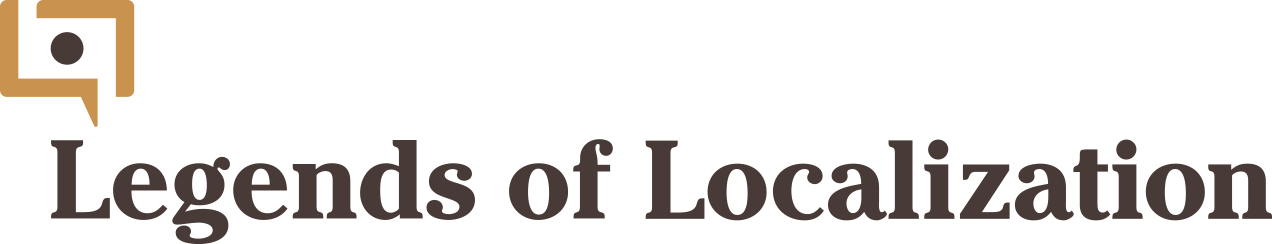

Similarly, the 王 (ō) character has several meanings. It’s generally translated as “king”, but it’s actually a little less gender-specific than in English. In fact, girls can be maōs too:

So, because translators often work without context, it’s not always safe to assume that a maō is male. Other meanings of 王 (ō) – such as “ruler” or “monarch” – can be useful alternatives.

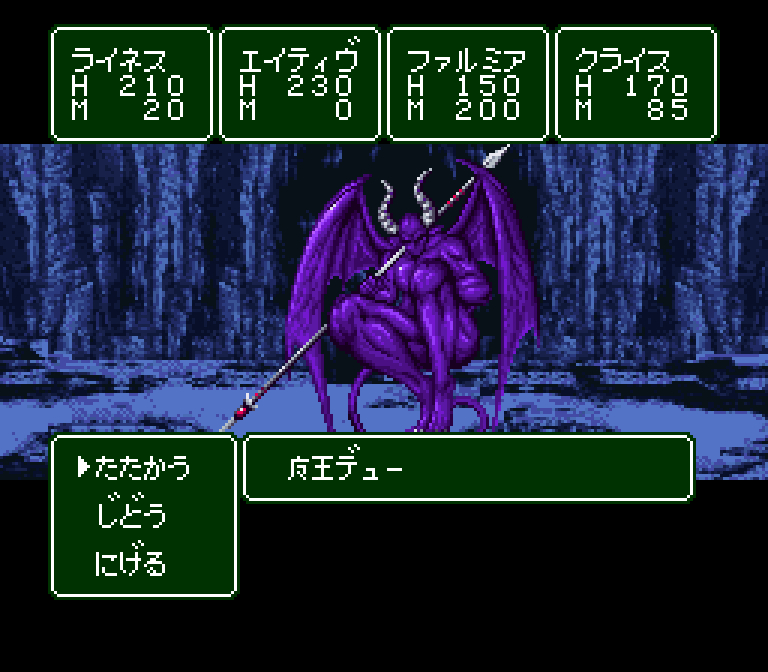

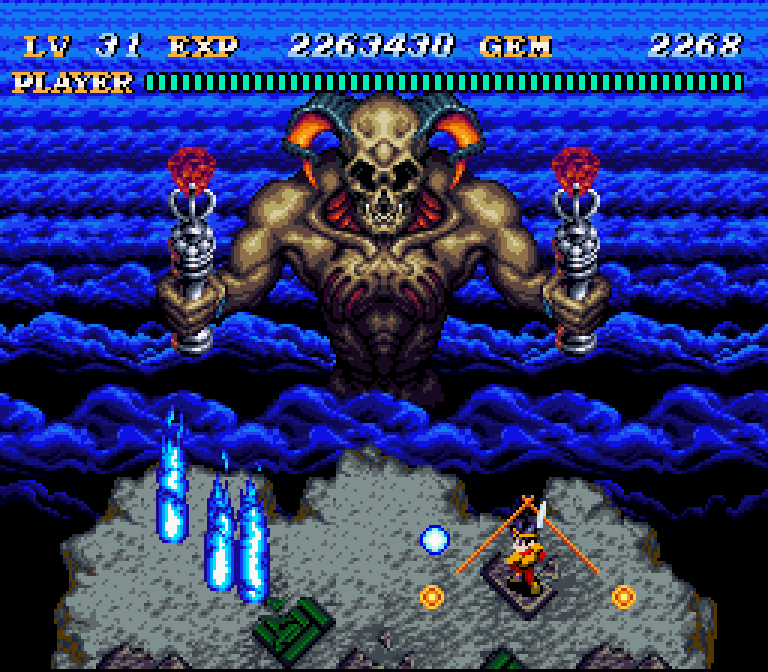

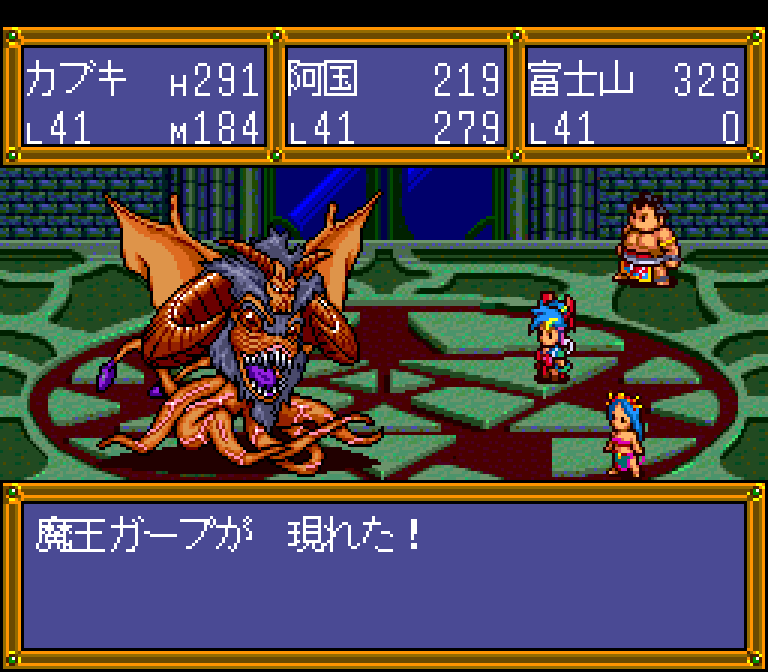

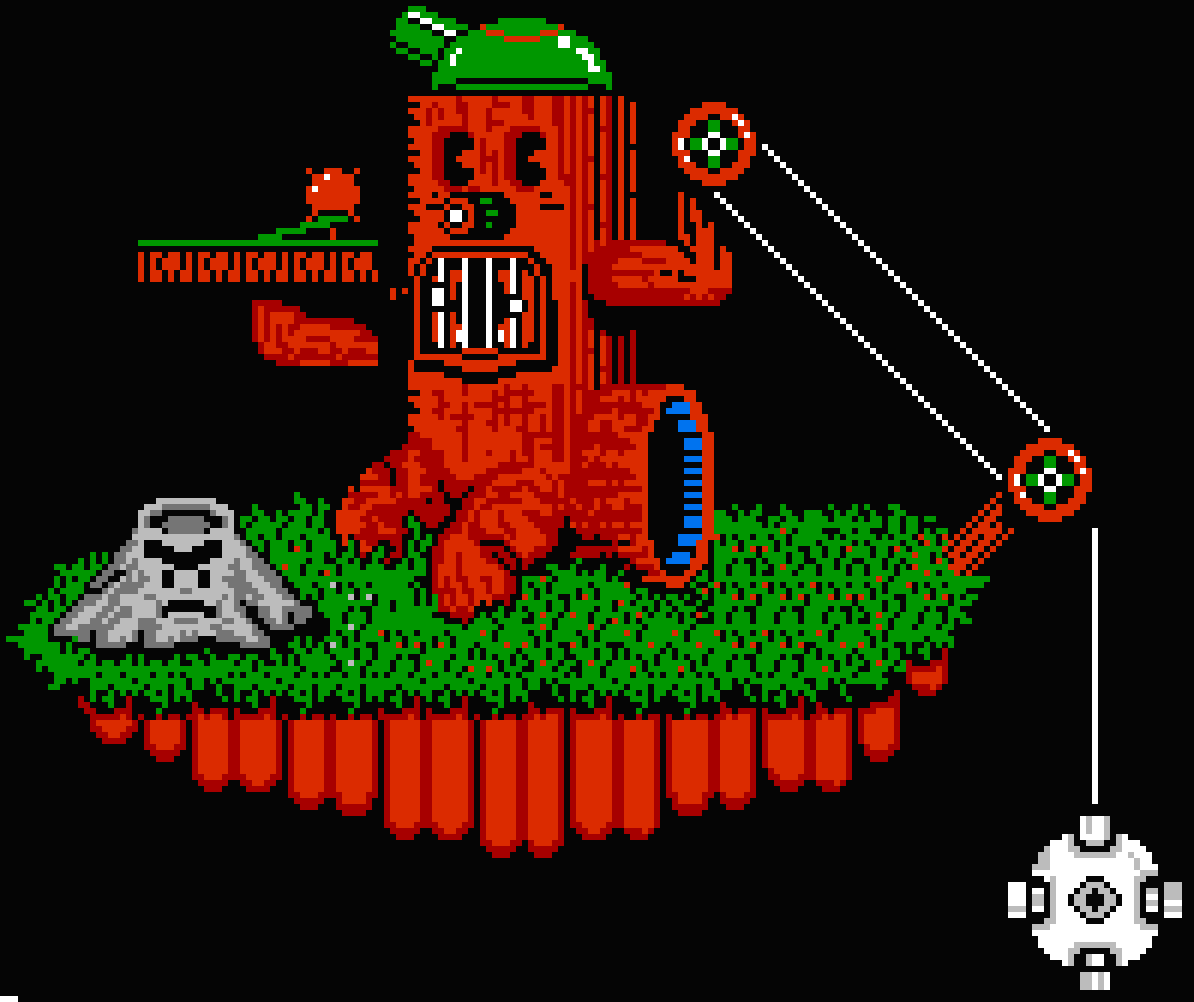

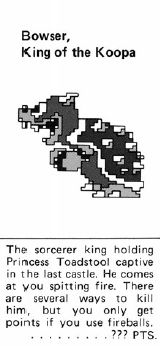

To complicate things even further, maōs come in all shapes and sizes. They’re often humanoid and have devil horns, but not always. Here’s a sampling of maōs from various games:

Even though all of these examples share the same title in Japanese, there’s no clear equivalent in English. So if a translator goes with Option #1, they’ll take the specific situation into consideration and tweak their wording from there.

Option #2: Focus on the Idea as a Whole

Taking a step back and looking at whole ideas is a key aspect to good translation. Translators who handle the word maō via Option #2 rely on creativity or outside resources to come up with a completely different word that still evokes the idea of the original.

Alternatively, a translator using Option #2 might consult dictionaries or look up how other translators have handled the word in the past.

Option #3: Write Around the Word

Since there’s no clear equivalent for maō in English, another option is to reframe things entirely. This can involve moving text around, adding all-new descriptive words, or just dropping the word entirely.

Option #4: Use What You’re Given

For example, when I worked on Dragon Ball way back when, the title for “Piccolo Daimaō” had already been chosen as “King Piccolo”, so I stuck with that. This option can be stress-relieving or frustrating depending on the situation. It can also get messy as new translators, companies, and series come and go, but that’s a topic for another time.

Option #5: Don’t Even Translate It

Yep, another option is leaving the word maō as-is. I rarely see it these days, but I’m sure it’s still common in fan communities that don’t need explanations of what a maō is.

As we’ve seen, maō and daimaō have a lot going on with them. They manage to describe a lot of things at once, all in one word. Translating them can be a challenge, but there are plenty of options to make it happen.

Maō / Daimaō Translations in Action

Because maō and daimaō are so complicated and involve so many variables, they get translated in different games in different ways. The examples below include games from the 1980s until today, and show how different translators have tackled the maō challenge.

The Longest Five Minutes (Switch, 2018)

This recent multi-platform game starts you at the final battle with the maō. Because it’s a sort of RPG parody/homage, the translators went with the straightforward “Demon King” title.

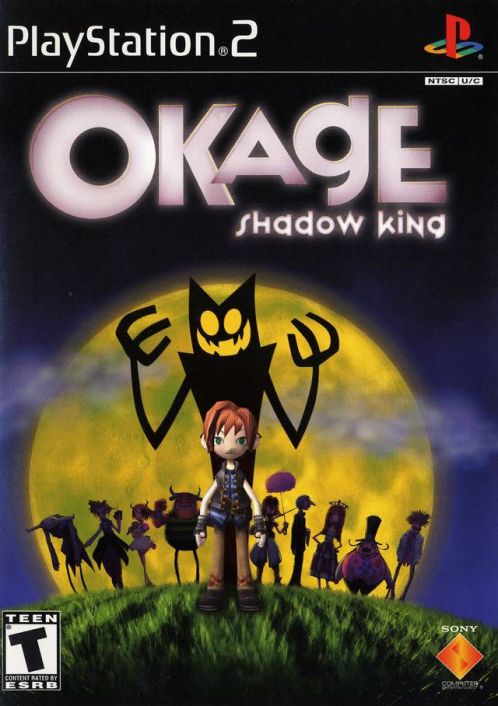

Okage: Shadow King (PlayStation 2, 2001)

This is a good example of a maō that doesn’t look human or demonic. The translators went with “Shadow King”, but if you look closely at the original Japanese title, you can see that the original publisher went with “Satan king” instead. In the actual English game, however, maō is translated as “Evil King” – so many inconsistencies!

The Legend of Zelda Series

The Zelda series is full of maō references. It’s also a good example of how inconsistent those references can be in translation.

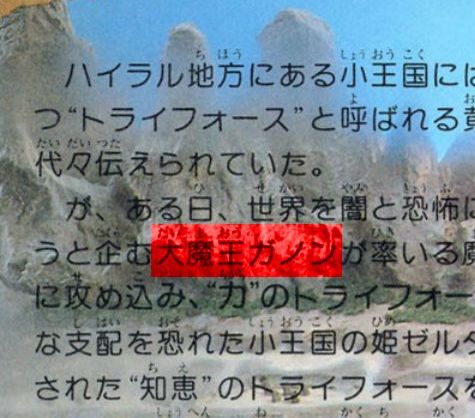

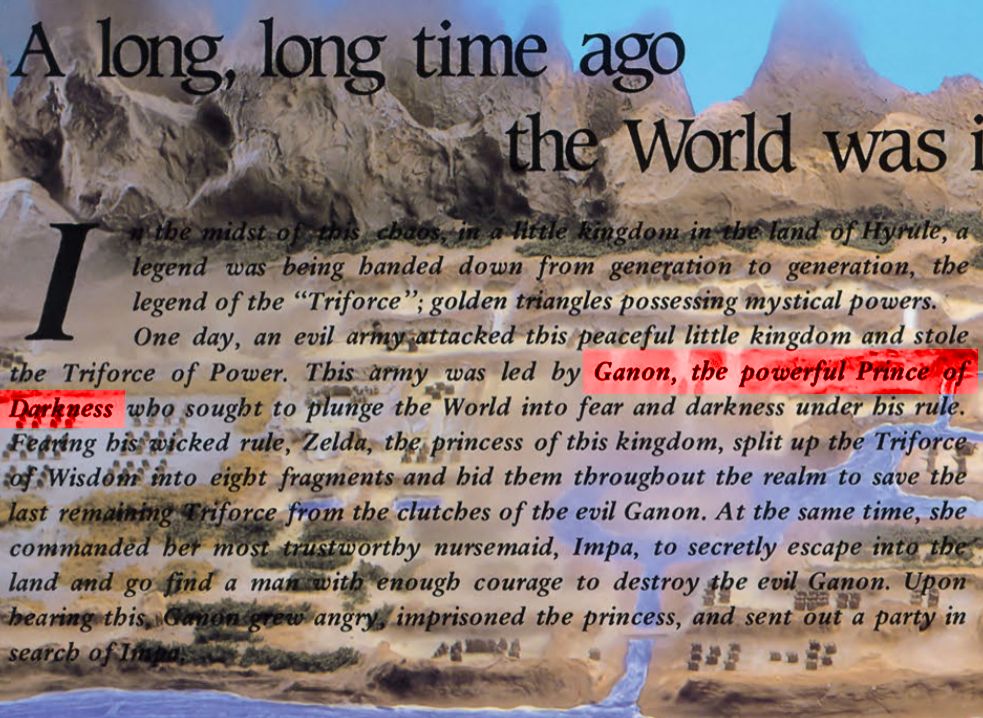

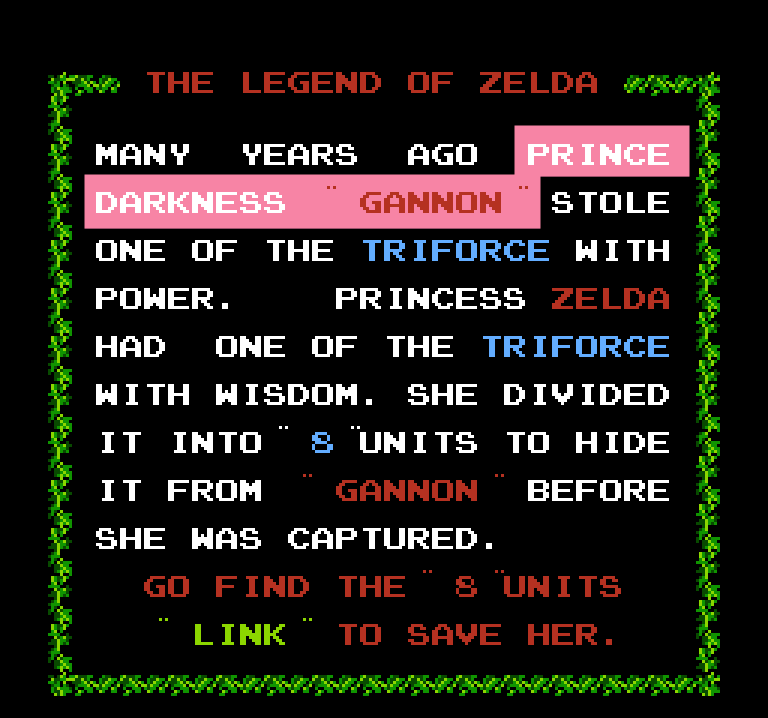

First, in the original Zelda (1987) game, Ganon is called a daimaō in Japanese. The instruction manual localizers went with “Prince of Darkness” while the actual game developers went with “Prince Darkness”:

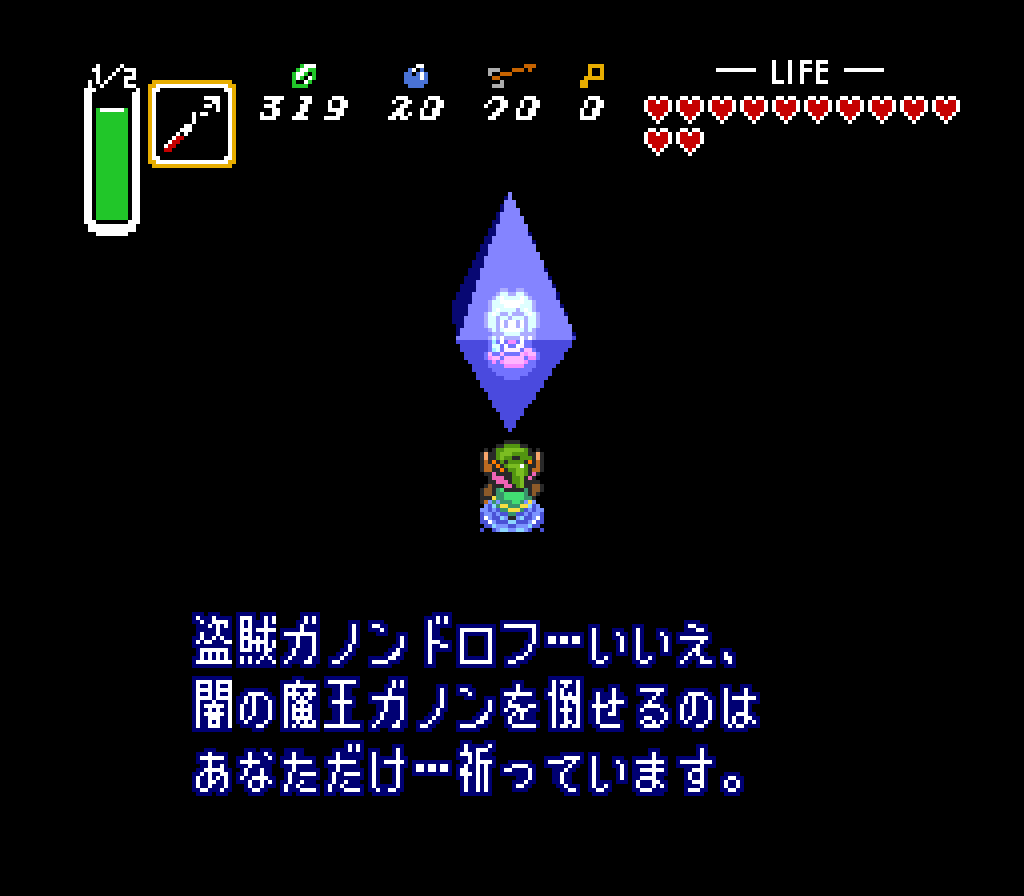

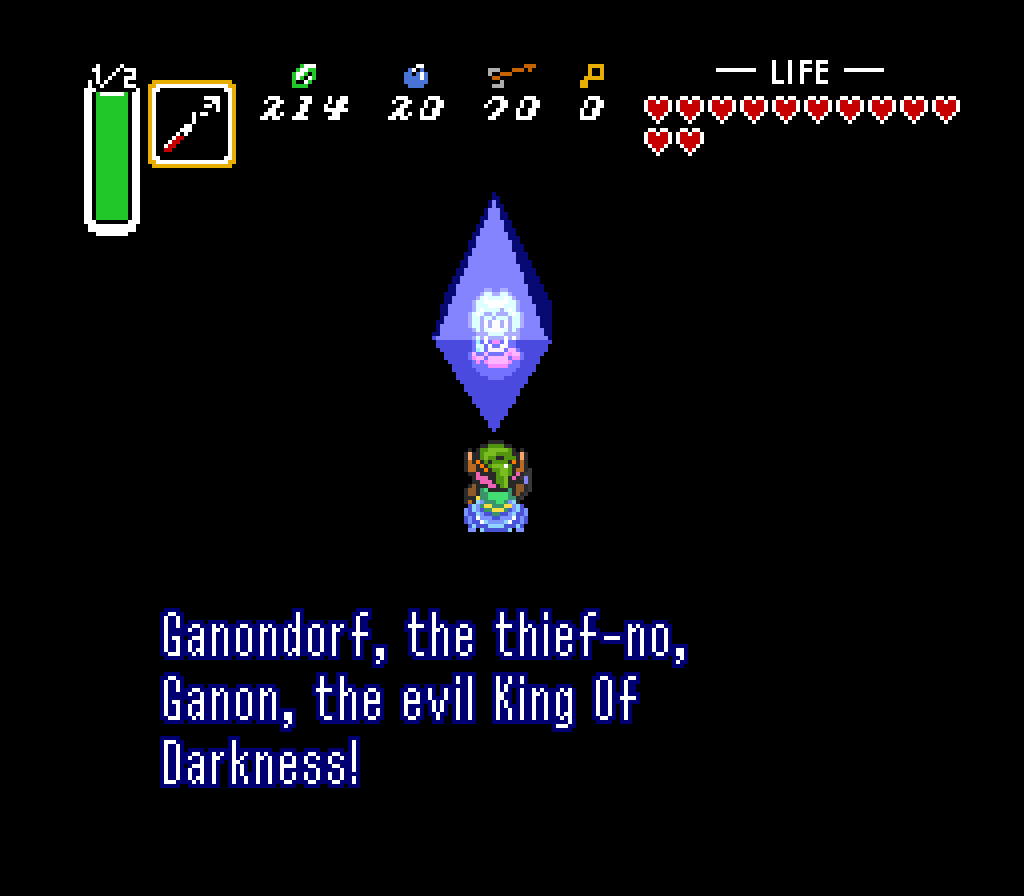

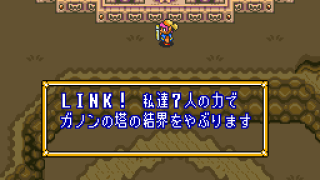

In A Link to the Past (1992), Ganondorf is now just a basic “maō of darkness” in Japanese and “the evil King of Darkness” in English:

Adding to the inconsistency is Ocarina of Time (1998), in which Ganondorf is known again as daimaō in Japanese, but now he’s the “Great King of Evil” in English:

Super Mario Bros. (NES, 1985)

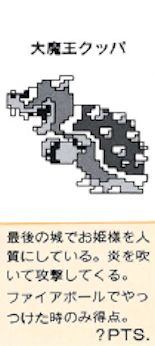

That’s right: both Ganon and Bowser share the same title. In the original Super Mario Bros., the daimaō was dropped and all-new text was used in its place. Even his actual name got changed!

We can also see that daimaō was rendered as “sorcerer king” in Bowser’s description. The Japanese description didn’t include daimaō at all, though – this is an example of Option #3: writing around the tricky word by moving things around and adding more info.

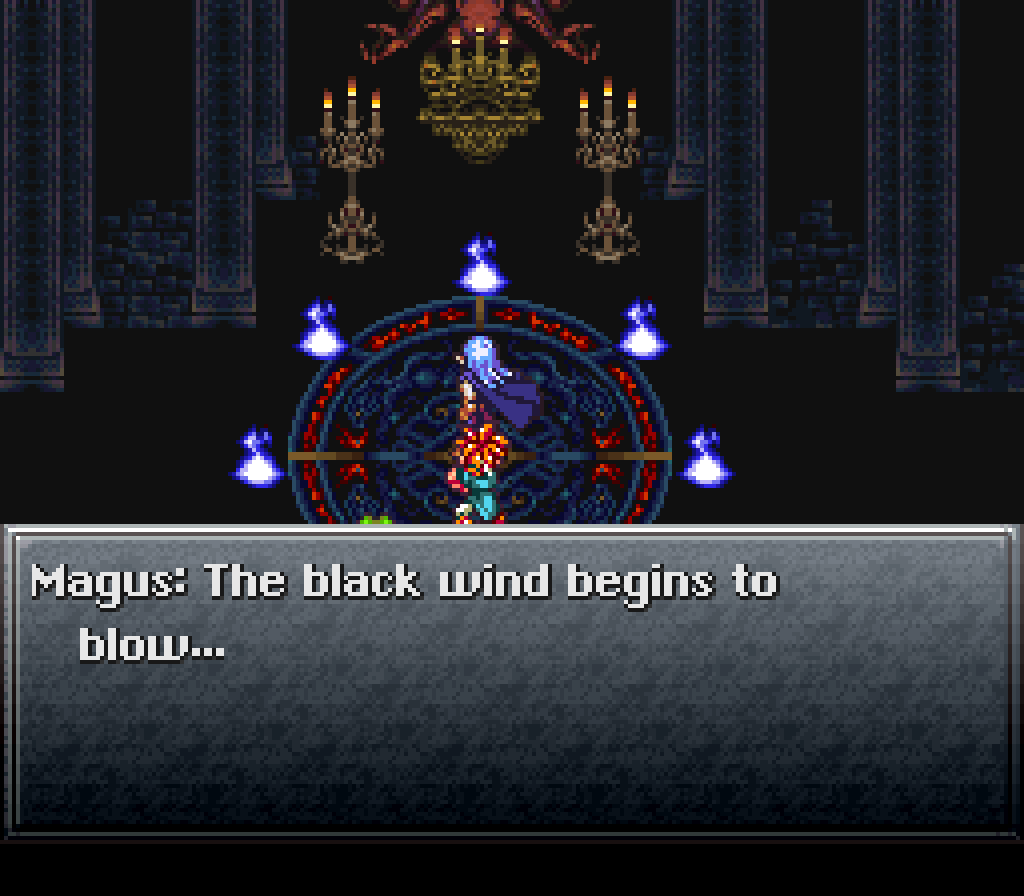

Chrono Trigger (Super NES, 1995)

One of the main characters in Chrono Trigger is simply referred to as the maō in Japanese. In the English version, he has an actual name instead: Magus.

This small detail adds weight to his choice to renounce his former name of Janus and simply go by the title of maō instead. It adds further weight when you consider that you can actually grant him a new name once he joins the party.

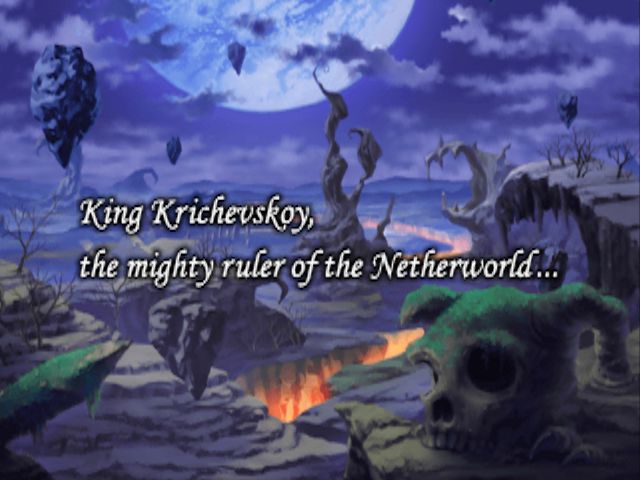

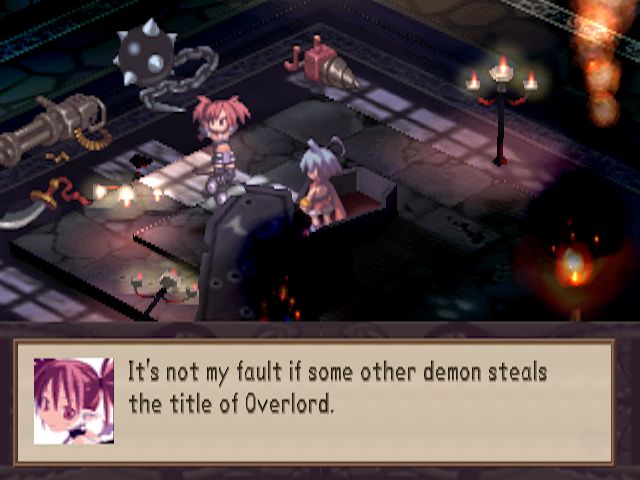

Disgaea: Hour of Darkness (PlayStation 2, 2003)

As we saw earlier, the prologue in Disgaea uses the word maō in Japanese but changes it to “King” and adds explanatory text in English:

Just a few minutes later, however, the word maō is now translated as “Overlord”. I believe this translation choice remains consistent throughout the rest of the game:

Lunar 2: Eternal Blue Complete (PlayStation, 2000)

At the beginning of the game, Lucia is considered the maō that must be exterminated. In English, the title of maō became “Destroyer”.

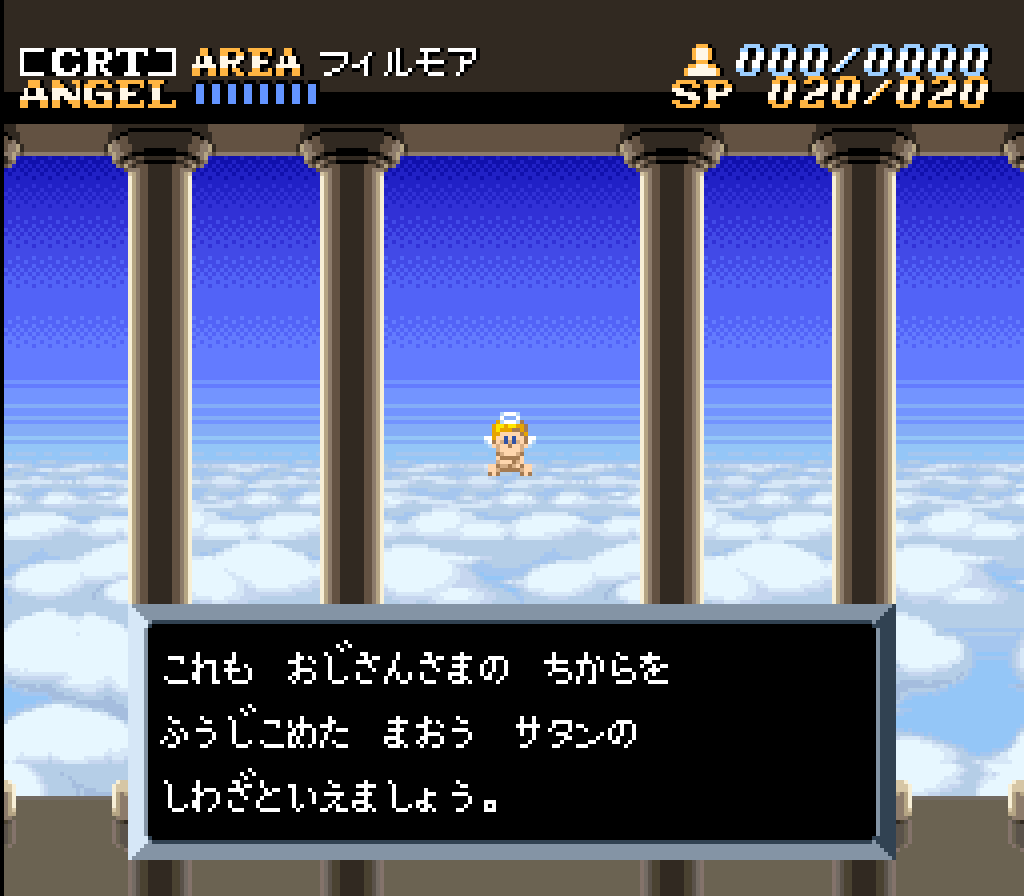

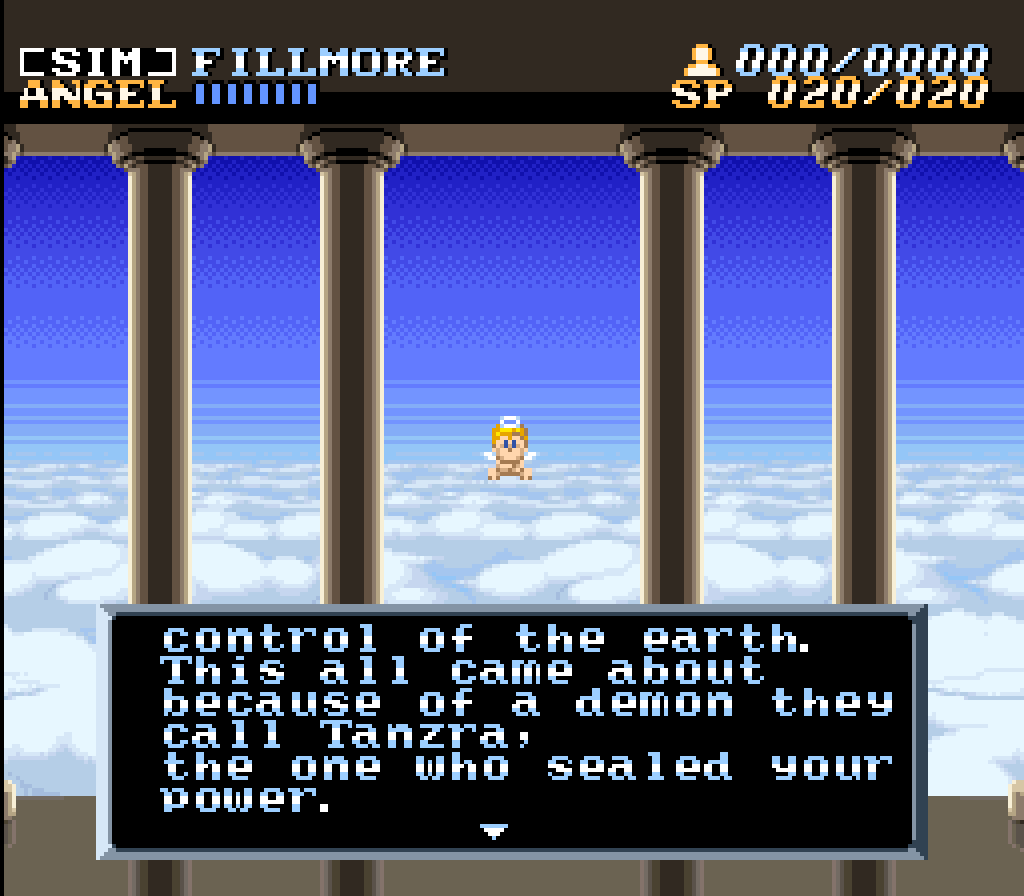

Actraiser (Super NES, 1991)

In the Japanese version of Actraiser, the final enemy is the maō Satan. In the English translation, maō became “demon” while his name changed to something removed from real-life religion: Tanzra.

Unholy Heights (Switch, 2017)

In this recent release, the maō-themed title was dropped entirely and replaced with a totally new idea.

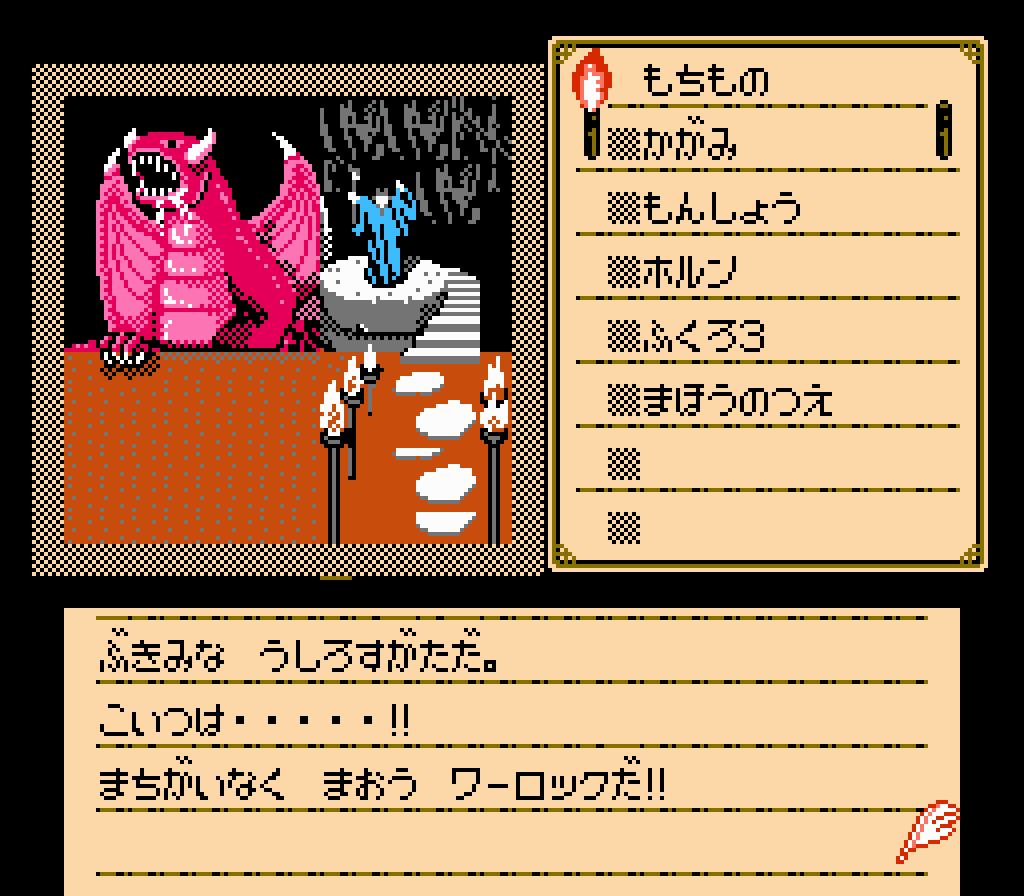

Shadowgate (NES, 1989)

Here’s an interesting case of an English game getting a maō added into its Japanese translation. The “Warlock Lord” in the English version of Shadowgate became the maō Warlock in Japanese.

Yes, I think they might’ve literally named the guy “Warlock”. If not, then he’s at least a maō now!

The Maō Hunt Continues

Have you seen any other translations of maō or daimaō in action? If so, let me know – I hope to update the list above over time.

Also, I plan to cover more tricky Japanese words in detail someday, such as omoshiroi and the infamous “it can’t be helped”. If you have any other suggestions, let me know on Twitter or in the comments!

I’d have to hunt down the videos on one of my extra hardrives, but a fansub for Ninja Sentai Kakuranger translated “Daimaou” as “Infernal Majesty/King (it depended on context). The reasoning being that it was used more akin to a title than an actual name for the character. Not sure what Shout Factory went with in their version.

I believe Shout Factory just left in untranslated.

Oh man, I bet sentai daimaous get translated in so many cool ways. That would be a cool topic to look into, but I know almost nothing about sentai to do it myself 🙁

I was just starting out with the language when I played Chrono Trigger in Japanese and was startled to see that, according to my dictionary, Magus was literally Satan.

Twenty-odd years later, I translated “maou” as “Big Bad” for the Assassination Classroom spin-off Koro Sensei Quest.

Haha, I can totally imagine fans back then spreading rumors about how they censored Chrono Trigger by changing his name from Satan to Magus.

You know, I wonder if translating “maou” for the first time could be a rite of passage for entertainment translators. Like, I wonder what my first professional “maou” turned out to be, and I’d be curious to know what it was for other translators too.

Nice work with the Assassination Classroom stuff BTW!

Nothing to add about maou, but I wanted to say that I really enjoyed this article and look forward to more in the series!

Thanks! I actually planned for this to be a simple gallery like the swearing gallery, but it took on a life of its own and unintentionally led to this new series idea. I’m looking forward to doing more like this, but wow is it gonna be hard to research some of them haha. What a pickle I put myself in!

The central villain of The Legend of Zelda: Tri Force Heroes is consistently referred to as a 魔女. Not sure if you want that on the same page?

That’s the word for “Witch,” I believe. Two of the original characters in Hyrule Warriors also bear the title, the white witch Lana and the black witch Cia.

Precisely. I love how the word for witch is just 魔 + woman.

Yeah, I find that words with 魔 in them tend to lead to a zillion different translations, although 魔女 is sort of an exception as it generally gets translated as “witch”. Even so, I do vaguely recall seeing alternative translations for it in the wild, so if I remember any (and if they’re interesting) I might possibly do a shorter article about the term.

Here in Italy the Piccolo Daimaou question was tackled in multiple ways.

-Manga originally translated it as “Grande Mago Piccolo” (Great Wizard Piccolo), but in later reprints they changed it to “Gran Demone Piccolo” (Grand Demon Piccolo)

-The anime just changed his name to “Al Satan” (creating a bit of confusion because that exact same name was already used for the Ox King; so when the big horned guy came back on the scene he was now called “Gyuma”, a shortened version of the Japanese Gyumaoh)

-Some videogame translated his name as “Piccolo, Signore dei Demoni” (Piccolo, Lord of the Demons)

Thanks! That’s some great info that I never would’ve learned without your help!

In case you’re interested in other oddities, the latin american dub of DB refers to Piccolo Daimaou as “Piccolo Daimakú” (strong U sound). Nobody is exactly sure of why. Also Kaioh-sama and Kami-sama were left as-is, perhaps due to lip-syncing or the translation team thinking those were whimsical enough.

Things get more complicated with the Thai Dragon Ball movie: https://youtu.be/SUuyUWJ_vQs?t=3m14s

(Be sure to turn on subtitles.)

Soul Blazer

“It can also look like the face of pure death taking its toll”

I see what you did there….

Haha, the thing is I haven’t even really played the game myself, but the final boss sticks in my mind after watching an LP of it for some reason. I really like how all of those Quintet games sort of felt connected too, even if it was just the font or sound effects or what have you.

Personally, i’m not a big fan of option #5. It just comes off to me as lazy to leave any word untranslated, like a particular N-word in some old One Piece fansubs which pisses me off everytime i hear it.

I agree, it gets especially annoying when people do Option #5 when there are perfectly fine translations available, just like nakama. Oh man, I remember when we started doing One Piece that so many fans immediately asked if we’d be leaving nakama in. I guess it’s not much of a thing anymore, judging by your comment?

I think the idea of leaving words like maou and nakama untranslated is part of a larger thing that’s been going on for decades in which we tend to romanticize some Japanese words if they don’t have strong 1:1 English equivalents. They become a special “uniquely Japanese concept” that isn’t really unique to Japan but just happens to have a convenient single word in Japanese. That could be an interesting article topic but it could easily end up sounding overly negative or haughty.

While it doesn’t seem nearly as common as it used to be, there are still some people who insist on using the word nakama. I regularly listen to the One Piece Podcast (which i totally think you should go on, given your past with the series), and they have a running joke of publicly shaming anyone that sends them an email or tweet with “the n-word” in it.

For me, at least, it’s less “uniquely Japanese concept” and more “nicely unique term to refer to a concept that otherwise doesn’t have a good way to single it out”.

In other words: adopting the term for a concept that otherwise wouldn’t be accessible in English. (And, arguably given the language’s history, expanding English in the process.)

That certainly doesn’t apply to every term that people might do this with, but it does to some, and IMO rejecting the practice entirely would be at least as bad as overdoing it.

It’s the case of a “purist” attitude. These sort of people worship the original Japanese culture and language, believing in a more idealized version of it than the actual thing. Yes, there are often perfectly acceptable alternatives, but don’t tell these guys (or gals). They’ll see that as a personal attack (and no, I’m not kidding about this manner).

Relevent ProZD video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvNxgHTWIlo

That pot with the dopey face in ハクション大魔王 was a thing that was turning us crazy at the Telefang Discord as we kept trying to figure out where the hell it comes from! That exact pot keeps coming back in many different references all over popular media.

So is the original origin of it actually ハクション大魔王? Does it have a name?

I checked Japanese Wikipedia and it only calls it the generic term of 魔法の壺, so something like “magic pot”. I’m guessing it doesn’t have a name based on that. I don’t know if it’s what started all your references or if maybe it’s just a sort of standard thing for magic pots to look like, but searching for these terms will bring lots of info + pics of it up: ハクション大魔王 つぼ

The anime title “Hataraku Maou-sama!” was translated as “The Devil is a Part-Timer!”

Also interesting is how Japanese games/amine/etc. change popular brand names to avoid copyright issues – in the one I just mentioned, he works at MgRonalds.

Another anime-related one: “Kyou Kara Maou!” (iirc would be translated as “You are the [Maou]!”) retained its Japanese name completely when localized, but they added an english subtitle to the effect of “god save the demon king” and it’s translated as demon king in the show itself.

I would assume that translating and localizing instances of “mazoku” in media is just as fun and varied. Demon race, evil race, etc.

There’s a bit more to the story than that. The main character’s name is Satan, which is probably why maou was translated as simply “the devil” in the title. Later however we find out that Satan is just a common demon name, and he isn’t actually THE Satan. In the light novel text itself, maou is usually translated more accurately as “devil king.”

Ooh, I love those copyright-avoiding changes in anime! I think there’s some really good tumblr page that catalogs them too.

Not copyright issues, trademark issues; Copyright does not cover term usage. Trademark does.

A trademark is a phrase or something else that identifies a particular brand or service. McDonald’s is an example of a trademarked term.

Copyright and trademarks are often lumped under “intellectual property”, along with patents and trade secrets, so confusing them is common.

And often a design can be both a trademark and under copyright, for example Starbucks’ siren logo, or the character of Ronald McDonald; however, in the United States, McDonald’s logo is a trademark, but probably not under copyright, because it doesn’t meet the threshold of originality required for copyright protection.

In that instance, the character’s name is actually just Satan. When he comes to Japan, he picks Maou as his Japanese human name because it’s the closest Japanese equivalent. Then the other characters call him stupid because of how obvious it makes his identity.

Maou (魔王) was indeed Satan’s title. His alias as a fast food employee, Maou, is written differently (真奥). (Still obvious, just not as much.)

That’s about as creative as Dracula calling themself Alucard… I mean sure you’re not outright SAYING it, but anyone can easily see the trick

Holy cow, I never even made the connection. It’s such a cute series, I never thought to look at the written source for that.

Nothing to add, unfortunately, but I really love it when developers do what they did with the Maison de MAOU/Unholy Heights title, bringing the little illustrative touches to the text along with the translation.

Yep! When I saw the Japanese title I was so excited to see if the title remained the same in the English version. Then I saw it used a creative localization AND creative graphic design – they put some real effort into it!

This kind of article is very useful. Thank you! This term specifically does cause quite a bit of headaches, the IGDA Localization Contest coming to mind, actually, with いきなり魔王 . So much fun.

Yep, seeing how everyone handled maou was a significant factor for choosing that game, actually. Among other challenges of course.

You know, I kinda want to do an article similar to this that shows how you can take one thing and give it to 50 different translators and you’ll get 50 unique translations back. I dunno if I’d be allowed to do that though, I’ll have to ask.

I still kick myself having come up with more creative names only after the fact xD Though I recall on one of your other articles you wrote this often happens in the profession.

I hope you get permission to do something like that! It’d be a great way to show how things really do differ by the translator : )

Before Hitler, Pharaoh was used as a generic term for evil ruler, maybe it would’ve worked as a good translation for Maou if it hadn’t been reduced to it current usage.

I’m surprised for all the works of fantasy we have, no term equivalent to Maou has ever come about. It’d be useful to have a proper word meaning big bad.

Hitler was Egyptian?

Neat, I hadn’t known that!

Pharaoh in some languages has biblical connotations with “tyrant”, I can see how where link came from.

I think the problem is rather maou in Japanese means so many different things that Archdemon and stuff are too specific to be a direct translation for. Speaking of which, even Dracula (castlevania) is a maou. There are times where they borrow Enma and Yomi (maybe Hades/Thanatos could work as a cultural translation?)

We do, though, don’t we? It’s “Dark Lord”, or more rarely “Evil Overlord”. I’m honestly pretty confused by the article’s claim that there’s no equivalent English term. Sure, it’s not a one-size-fits-all translation, but if you introduce a character in a fantasy setting as “the Dark Lord”, an English audience is immediately going to make the same assumptions that a Japanese audience would make if the character was introduced as “Maou”.

Couldn’t “mao” be simply translated as “villain”?

From a bare-bones conceptual point, “villain” could work if you’re trying to highlight how it’s the polar opposite of the cliche hero. But by itself I don’t feel “villain” conveys the idea of a supreme supernatural being. “Maou” also sometimes does involve royalty as well, which “villain” by itself doesn’t convey. I think it’s also possible for some maous to not be villainous, so it’s hard to pin a one-word-fits-all English equivalent to “maou”. It’s tough.

Magus is definitely used as a name in Chrono Trigger, but it’s worth mentioning that the word actually started as the term for an ancient Persian priest, and was used as an occult title by guys like Alistair Crowley for decades before Chrono Trigger. That’s what makes the name so great, it could be a name OR a title like mao, depending on how you look at it.

Couple of things: First of all, Magus is the singular form of Magi, the wisemen from the biblical nativity story. Second, the DS port of Chrono Trigger, with its retranslation, actually does kind of subtly imply that Magus is a title rather then a name. It’s something you really have to pay attention to catch, as it is rather subtle.

Dang it, I need to play the DS version of CT someday finally, I feel so out of the loop haha. I should probably do the same with FF6 GBA. If I do play CT DS I’ll be sure to keep an eye out for the Magus/title thing.

魔王 was translated (haphazardly) as “Fiendlord” in the DS version, that might be what above poster was referring to.

Yeah, I had considered bringing up the details of “magus” but I didn’t want to stray too far off track. I didn’t know it went all the way back to ancient Persian stuff though, cool!

The word “magus” actually has two meanings, though related. One is the singular for “magi”, as in the priests of Zoroastrianism (which was the official religion of Iran/Persia in ancient times). More specifically, it later referred to a certain sub-sect of Zoroastrianism that had sprung up in Safavid times.

The other meaning, however, is of an actual magician, though it seems it was mostly used by the Greeks in this sense. This is because the Greeks believed Zoroaster (the prophet of Zoroastrianism) to have invented magic, as well as astrology. What the original, Old Iranian word “magus” (or whatever it was derived from) /actually/ meant is unknown.

So Magus being both a title and descriptive of what he does (him being the most powerful magician and all) is a good choice. Combined with the medieval stigma for magic, which is the era he’s vilified and encountered in, makes it a pretty great equivalent for Maou.

It’s interesting to me that video games were writing around the word “Satan” by *adding* the words “demon” and “devil,” while, at exactly the same time, TSR was writing around the words “demon” and “devil” with ridiculous bafflegab:

https://1d4chan.org/wiki/Tanar'ri

https://1d4chan.org/wiki/Baatezu

I was surprised to see that they used the word demon in Actraiser here, I guess it might mark a time just before NOA got especially heavy-handed with that sort of stuff. I’m not familiar with D&D stuff much so that’s a good point you make. I assume it was because they had been directly pulled into all that religious ruckus before then.

More or less, yeah. Lorraine Williams — the new CEO — ordered all such terms scrubbed because she was paranoid about the brand being associated any further with religious controversy following Jack Chick’s amazing anti-D&D tract: https://www.chick.com/reading/tracts/0046/0046_01.asp

I want to say that Miitopia used both of these terms, for what was localized as Dark Lord and Darker Lord. I don’t know for sure, though, because I haven’t actually played the game in japanese.

I’m not familiar with the game but a quick search shows that at least 大魔王 is one of them. I can’t figure out what the other one is in Japanese, though.

I looked around a bit, and managed to find it. Seems to be 超魔王.

https://i.imgur.com/j57C3ay.png

So basically you have 大魔王 “Great Maou” and 超魔王 “Super Maou”, lol

The Italian translation went with “Duke of evil” (first one), “Grandduke of evil” (second one) and “Archduke of evil” (the final boss form of the second one, “Darkest Lord” in English).

G Senjou no Maou was a fun example of this because it’s part of the title and the titular character took advantage of the versatile concept of maou by implementing it in several ways, including the devil/satan usage, the RPG last boss usage, and most of all its use as the translation of Erlkönig from the Goethe poem.

Unfortunately I wasn’t a talented translator so I just kind of threw up my arms and said screw it lol

Whoa, that multi-usage of maou sounds really cool!

This didn’t occur to me until now, but thinking back to Chrono Trigger, it seems very likely that in the Japanese version, you were meant to initially think that the references to a “mao” leading the demon side were describing a generic demon-king sort of enemy (the sort of opponent you’d expect to find as the end boss of a generic medieval fantasy RPG realm), making his appearance as a human prettyboy a surprise. Especially given that the rest of his side are inhuman monsters, of course.

Disgaea is an interesting case because Laharl uses the word like every five seconds and it’s the focus of a major part of the plot. That’s probably why they went with a snappy single-word translation most of the time.

Wow, that’s an excellent observation. I don’t recall how he’s described/explained/introduced in the English version off the top of my head, but that could be something else that got lost when the Magus name was inserted.

There is definitely at least one point in the Woolsey translation where he is referred to as “the Magus,” and I’m fairly sure it’s before you meet him in person. I wish I could remember exactly where it is–I think it might be flavour text from an NPC.

Found it–Truce Inn 600 A.D. in during “The Queen Returns”

[Young Man]

The Magus’s army destroyed Zenan

Bridge, so the south continent is

inaccessible.

Oh, and!

[Fiona’s Villa, 600 A.D.]

FIONA: Many trees were destroyed in

the war with the Magus’s Army.

I try to maintain the forest by

replanting trees, but they all die.

I always read that latter, at least, as more a clunky way of attempting to say “the army of Magus” than an attempt to refer to the army’s commander as “the Magus”. So if it was an attempt to convey that detail, it didn’t work as well as it might have done…

Carlsen Comics’ Dragonball translations (which were initially in German, though that German translation then got used as the base of other translations into a multitude of other languages) translated Piccolo-daimao as “Piccolo the Archdevil”, which I thought was a really good choice. I had those Funi Dragonball DVDs you worked on, though, and while I can’t remember how you translated the term, I’m 100% certain it wasn’t “King Piccolo”.

One thing you slightly touch on but might want to go into a bit more detail on is how the term can also be used about genies, though. The “daimao “in Hakushon-daimao’s title is definitely not meant to imply the guy is in any way evil.

Also, as an aside, the Swedish translation of Shadowgate translated “the warlock lord” as “Lord Warlock”, turning his title into his name.

Another maō in action, one that was brought up in the image gallery, but not in the list, was the Tyrant Race in Shin Megami Tensei. It would have been easy to simply translate maō as “Evil Lord” or “Demon King”, but luckily we got the more colorful localization “Tyrant”.

Also, while we’re on the subject, If you’re interested in how (unsurprisingly) closely intertwined the magical-evil-demon filled Shin Megami Tensei is with ‘ma’, here’s a link I remembered.

http://eirikrjs.tumblr.com/post/104021841812/the-mystery-of-魔

And if the franchise’s history of localization interested you even more, the grumpy old man that authored the previous article has even more on SMT3. Bonus points for linking to your website in part 1. This is a pretty nice website after all.

https://personacentral.com/nocturnal-revelations-the-legacy-of-shin-megami-tenseis-first-localization-part-3/

I recently got my hands on the English Dragon Ball manga volumes, and read through the whole thing from beginning to end. If I remember correctly, how they handled Piccolo’s title was that sometimes they’d say Piccolo-daimao, and other times they’d say Demon King Piccolo or Great Demon King Piccolo. But it was pretty clear through the dialog that they were interchangeable and meant the same thing.

They did the same with a lot of the characters’ special moves, where they’d be in Japanese, but it would make sure it was clear what they meant in English, either through surrounding dialog or through footnotes. In fact, i remember one funny joke during the first tournament arc where Jackie Chun calls out a fancy attack name, and then proceeds to sing a lullaby and put Goku to sleep. When the ref questions if it was a real martial arts move, he replies “Why not? It’s got a fancy Japanese name, doesn’t it?”

While an above post i made said i normally find untranslated words to be lazy, this was actually one case where i think it was done well. This is an obviously Japanese-inspired setting, they are mainly names and titles left in Japanese, and it still makes it clear what each name means. It’s pretty much the same criteria i use when it comes to Japanese honorifics in manga. If a series clearly takes place in Japan, i feel it’s okay to leave honorifics in. But in, say, a manga based on The Legend of Zelda, it just feels really weird to have everyone saying “Link-kun” and “Zelda-sama”. (As a side note, that trainwreck of translation was what finally put me off of manga scanslations for good. Thank God Viz later licensed that series and gave it a good translation.)

So yeah, expanding on what i said in an earlier post, I am okay with occasionally leaving things in Japanese some of the time, but only under certain situations and if it’s still written well.

>They did the same with a lot of the characters’ special moves, where they’d be in Japanese, but it would make sure it was clear what they meant in English, either through surrounding dialog or through footnotes.

Carlsen sometimes did this as well, usually by tossing in a translation of the name as a description of the technique, so you’d get stuff like “Mafuba, the art of capturing a devil” and “Genki Dama, the energy ball technique”. It’s a decent enough way of doing it.

Damn, I think my somewhat lengthy post disappeared into the internet black hole. Or maybe you curate posts now?

Anyways, in short, Shin Megami Tensei localizes the ‘mao’ Race title (Race being a classification system for the Demons) as the Tyrant Race. You show a picture of this in the gallery, but it’s not in the list of examples.

Also, while you’re on the subject of ‘mao’, ‘ma’ has a pretty close relationship with Shin Megami Tensei than might interest you.

http://eirikrjs.tumblr.com/post/104021841812/the-mystery-of-魔

I assume they went with “Tyrant” because it’s very short; SMT race names need to fit on a lot of screens that don’t have a huge amount of space (same with “Fallen” for Fallen Angel.) No way “Demon King” would have fit everywhere.

I recall that the old AGTP fan-translations left all the race names in Japanese. In fact, even the official translations are inconsistent – they translated a lot of them, but they threw up their hands and anglicized Jirae, Jaki, Touki, Yoma, Genma, Tenma, Kishin, Kunitsu, Megami, Amatsu…

Looking over which races got translated and which didn’t, it’s notable that untranslated races tend to consist of mostly creatures from Eastern myths and legends, while the translated races are heavily Western. I wonder if they did that deliberately? That’s the only reason I can think of why they gave us the somewhat-creative Maou -> Tyrant while leaving Megami untranslated despite it having a clear and unambiguous translation; Maou is stuffed full of Christian demons, while Megami consists entirely of Eastern goddesses. Of course, they might also have left Megami untranslated because it’s in the title of the series.

And they were also constrained in that they absolutely couldn’t use the word “Demon” anywhere in the translation of Maou because that word is used as a generic term for SMT spirits and would give a misleading impression if Maou / Tyrants were described in a way that implied that they led demons in general.

While going over the races… I wonder why they translated Tenshi as “Divine?” Maybe they wanted it to sound like a title, since enemies are usually introduced with [race] [name]. Daitenshi was translated as Seraph and then as Herald, which I think somewhat misses the fact that Daitenshi is meant to be a higher form of the Tenshi race… and that’s something that actually matters a little bit in SMT, since it guides fusion logic. It’s weird, since “Angel” and “Archangel” are such obvious translations. Maybe they wanted to reserve those for monster names, though; it looks like the monsters unambiguously had those names in Japanese, too, which must have been what gave translators their problem. They were lucky that the iconic monster of the Yousei / Fairy race is called “Pixie” and not “Fairy”, I guess.

Oh, it looks like it got caught in the moderation queue because it was so big and had so many links. Darn you automated spam thingy! But it’s okay, I approved it so it should be somewhere in this thread now.

What of Ghaleon’s title from the first Lunar game? I’ve never heard its Japanese form referred to, but in English, it’s “Magic Emperor”. I’d be shocked if that WASN’T a result of your Option #1.

It’s actually pretty elegant, though, since he was a magic-user even before his heel turn, thus justifying the use of “Magic”, and “Emperor” does tend to have a bit of a negative connotation to it that “King” may not. Thus, “Magic Emperor” covers both his abilities and alignment, while mostly retaining the spirit of the maou title (assuming that’s what it was, of course).

Nope, it’s literally the same, Magic Emperor. 魔法皇帝. However! The hordes he commands are the Mazoku, one of the same ambiguous “evil clans” that a Maou would rule over. Vile Tribe in the US translation’s case.

Oh, and since you asked for suggestions for other tricky phrases to translate, my suggestion would be “so iu kedo” and its variants.

I dunno, that doesn’t sound too complicated to translate? “That said, …” is a literal translation that also sounds completely natural, at least for certain kinds of people.

The Yu-Gi-Oh! card game has a whooole bunch of Maō, translated flavourfully depending on the card. For example, “Maōryū Beelze” becomes “Beelze of the Diabolic Dragons”, “Hametsu no Maō Garlandolf” becomes just “Garlandolf, King of Destruction”, and “Maō Diabolos” becomes “Diabolos, King of the Abyss”.

Yu-Gi-Oh! card names are interesting from a translation perspective because they operate under a lot of unique constraints. In particular, unlike MTG (which puts every “tribal” signifier in the creature’s summon line), Yu-Gi-Oh will very frequently have cards that care about a specific word or phrase in a card name – eg. the “Demon” / “Archfiend” archetype is just any card with that word in its name, which is all that cards that search for or boost it will look for. This causes no end of headaches because sometimes these archetypes will apply retroactively to cards printed and translated before the specific word they care about had any important rules meaning – and sometimes they were translated in different ways. eg. Summoned Skull was デーモンの召喚, summoned demon, which of course meant it was treated as a demon because it had デーモン in its Japanese name. But it was printed before “demon” was an archetype with rules significance, so the translators (who were trying to avoid referring to demonic things) gave it a name that didn’t match with what later demon cards were translated as (“Archfiend”). English reprints of those cards have rules text clarifying that it’s treated as a member of that archetype.

Similarly, they might one day print a card that says “search through your deck for a Maō card and put it in your hand”, which will cause massive headaches for English players.

Nowadays I assume they’re forced to translate most card names consistently on a word-for-word basis to avoid that problem, which probably contributes to Yu-Gi-Oh’s reputation for having weird or awkward titles. Or perhaps nowadays there’s a rule that all archetypes have to be established in advance and can’t refer to previously-printed names? Hm. Either way, it’s an example of how, in a serial work, a translation decision that seems reasonable at the time can turn out to cause problems down the road.

(The infamous Ace Attorney localization is similar – if you just look at the first game, moving it to America doesn’t seem like a big deal, since there’s not many references to where it takes place. But then later cases kept inserting stuff that overtly and unambiguously set it in Japan, like murders in enormous Shinto shrines or entire cases revolving around Tengu-themed villages, eventually leading to the point where localizing The Great Ace Attorney in a way that fit in with the setting established in previous localizations simply wasn’t possible. No amount of clever translation was going to make Meiji-era Japan look like 19th-century California.)

Rules that reference specific phrases in names of already-translated items always, always screw translations over. See also those Pokemon abilities that affect moves whose names share a certain quality. In every version other than the original Japanese, they end up affecting some random list of moves you’ll have to look up online because there’s no real way for anyone to deduce what it is.

It’s a completely unavoidable byproduct of playing a translated version of a constantly-updated game with complex rules.

Are you talking about how Meteor Mash is a punching move, and Sucker Punch isn’t? I know the reasons why, by the way.

I have a suggestion for another tricky Japanese phrase! I’m not sure if you’ve done an article on it yet, but I see 四天王 aaaaall the time in Japanese media, and it would be cool to see some of the different ways it’s been translated besides the usual “Four Heavenly Kings”.

Yeah yeah! We’re gonna do one on the Four Heavenly Kings 😀

Seeing Beelzebub from SMT made me realize that those types of demons are from the “Maō” clan. In English, they called the clan “Tyrant.” Maō/Tyrant demons are the most powerful, chaotic demons, and includes the likes of Lucifer and Asura.

Interesting word to use in this case, as it would imply that they are rulers of sorts (which isn’t necessarily always the case!)

Here’s an interesting example you may have not heard about:

NieR: Replicant is a post-apocalyptic game and features a race called 魔物. They are led by a character named 魔王. And well, Replicant is kinda a parody/satire of games like Ocarina of Time, so it makes sense that the whole story is structured like a Dragon Quest game. You are the hero who needs to kill the 魔王 to save the world. The meta in NieR: Replicant serves a purpose because it intentionally misguides you into making the whole situation worse. Without giving spoilers away, I’ll just say that the names are intentionally video game-y to show how we have conditioned ourselves to kill things without questioning in video games.

The translation, NieR: Gestalt, goes for a different route. It seems to be more inspired by God of War (the translation has its own unique protagonist to boot, a manlier muscular version) and the translation is very spiced up. While Replicant likes to call towns with generic names and so on, Gestalt adds a lot of flavor to the setting. In regards to the 魔物 and 魔王, the translation calls them Shades and Shadowlord. This translation has obviously lost the video game meta connection, though it has interestingly added some attributes to the lore. The connection between Shades and Shadowlord is made explicit and for anyone who is quite good at guessing some plot could figure out what they really are. I do wish the translation kept the meta connection somehow.

Anyway, this is really cool article that has explained the basics and more. I have difficulty explaining what makes 魔王 characters quite interesting to people who don’t know Japanese. Tales of Berseria, for example, is about a Maou who swears vengeance on the Eiyuu/Hero for ruining her life. It’s that little bit of meta that makes you realize how Japanese RPGs are in a great conversation about what is the meaning of a hero and their antagonist.

I’m looking forward to you tackling more tricky translations like this!

The Rance series ended up having to retranslate this term multiple ways because it’s a long-running series that switch hands a lot and only recently has official releases rather than fantranslation. And also because of “this concept name is already being used by something else”

It’s obviously supposed to bring up the old “Hero and Demon King” symbolism, so it should have been just a simple replacement of “Demon King” and “Demons” (魔人) as the DK’s subordinates, except for the little catch on the whole gender neutral thing – half of the “Demon Kings”, including the current one, are women so the translators were worried about confusion.

Later they used “Demon Lord” for Maou and then “Dark Lord” for Majin – presumably because it’s less gendered and to convey that Majins were actually pretty high up on the hierarchy and not common mooks.

So this part is a bit of a blur to me since the game hasn’t gotten its official release and I only remember it from discussions – one of the games takes place in a Japanese-like setting and Onis were introduced as a concept, and while the fantranslation decided to just leave it as Oni, I think they decided that Oni should be translated as “Demon” in the official release.

Because of this, Maou/Majin got retranslated as “Archfiend” and “Fiend” respectively. There’s a lot of theories as to why they went for that, like how the Maou concept in Rance is actually very vampiric (the Maou creates Majins by having them drink his blood, when they die they turn into “blood souls” etc) and they probably think that Fiend would convey that intention much better.

There’s also a pun name enemy that turned into “Archfriend” (it was DaiMyaoh or something similar in the original Japanese version)

It wasn’t a very popular decision as far as I can tell and most people just use one of the earlier translations (though just writing it as Maou isn’t very common either), so I guess that’s the danger of setting precedents.

The first thing that springs to my mind for “tricky Japanese words” is “maboroshi”, since while it’s relatively easy to understand the concept, I’ve never yet found a short way of translating it that works in more than a handful of contexts. The best I’ve found is “unrevealed”, but that looks odd – and doesn’t really convey the feeling/nuance/etc. – in English in pretty much every case where I’ve found “maboroshi” used.

Somewhat similarly, I’m not sure I’ve ever found a succinct way of conveying the sense of “yare, yare” as I understand it, at all.

Less in the “tricky” than in the “frequently mistranslated” vein would be “itadakimasu”; it tends to get contextual translations in my (fairly limited) experience, but I can’t remember having found a context where it wouldn’t make sense to render it as “don’t mind if I do”. (Except possibly for formality-level mismatch, but you can’t have everything…)

“Mythical” is a pretty solid stock translation for “maboroshi no” that works in the majority of contexts it pops up in.

That only works if there are myths about it, though, and still doesn’t convey the actual underlying idea in at least some cases.

I recall having encountered it in contexts where the intended meaning appeared to range from something like “we don’t know where to find it” to “we don’t understand what it is/does”, passing through something closer to that “mythical” on the way. (Though most if not all of those contexts were encountered long enough ago that I probably couldn’t dredge up what they were.)

Possibly I’m misunderstanding the word and overcomplicating things, but I’m not at all satisfied with “mythical” as a generic translation for even a majority – much less the great bulk – of cases.

I don’t know how accurate a translation this is but I’ve seen the production name for what would end up being the second Pokemon movie, Maboroshi no Pokémon X, translated as “Phantom Pokémon X”. Though the end version was “Revelation Lugia” (and the dub was Pokémon 2000 The Power of One)

“Mythical” is a pretty solid stock translation for “maboroshi no” that works in the majority of contexts it pops up in.

Another example of Maou that I was just reading:

The fan translations for Kumo Desu ga, Nani ka? translate Maou as Demon King normally, but leaves it untranslated when the Demon King starts calling herself “Maou Shoujo Ariel-chan”, probably because the joke wouldn’t translate well and they assumed most readers would know what the words mean well enough to get it.

(And the fact that the joke references real-world pop-culture is actually mildly plot-important, too, so they couldn’t just omit it.)

Digimon has the 七大魔王 – fans referred to them as the Seven Great Demon Lords. Each one corresponds to a deadly sin, though, and with Cyber Sleuth finally came an official translation: the Seven Deadly Digimon.

This is probably a bit offtopic, but regarding Dragon Ball and Piccolo Daimao, there’s a very curious case in the catalan and french translations. I grew up watching the anime in catalan and this character was called first as “Satanás Cor Petit” (Satan Little Heart). The catalan’s translation (as well as the spanish, galician and other languages of Spain) was mainly based in the french translation, and just few years ago I realized Piccolo was called as “Petit Cœur” in France. That’s a example of a messed translation, not just because the unusual japanese word but because of a mistranslation based in another mistranslation. I can understand very well how hard this was for translators, especially since this happened in times when both internet and Dragon Ball was not as popular as today and they couldn’t get the proper info to do things right.

In the anime, Piccolo Daimao is also sometimes called as “el rei dels dimonis” (something like Demon King) while his son was sometimes called as “el princep de les tenebras” (the evil prince), though this title nearly dissapeared when he became good. That was probably in reference of the also common name “Demon King” that was used for this character, because the catalan dub also got some of the sources from the english translation and not all from the french. If I’m not mistaken, they used the french in the first sagas while many of the Z and later sagas got the english one.

As said this is probably just offtopic and not interesting stuff since this blog seems to be about english and japanese only, but just had to comment this curious example just in case 😛

A lot of Dragonball translations were crosstranslated off each other, with most European dubs of the anime being translations of the French dub.

“Conquest of the Crystal Palace” (Maten Douji) for the NES comes to mind, as in the Japanese version the final boss, Zaras, is a daimou.

The English version of the game even leaves the kanji stage names untranslated. So 魔 appears quite often when referring to the boss and final stage.

The Devil from “Devil World” is likely also one. Indeed, daimou is often translated as “Demon King” “King of Darkness” or “Devil”

I think the Mao/Daimao case is one of those situations where something is so often translated literally (in this case, as Demon King/Great Demon King) that the literal translation becomes, in itself, a trope present across the medium that fans will instantly recognize, even if a native English speaker writing a fantasy novel would probably not describe a villain as a “demon King”.

We could call this the “It can’t be helped” syndrome.

For what it’s worth the Japanese Wikipedia page for the Witch-king of Angmar has his name translated as アングマールの魔王 (Angumâru no maou), the chiefest of the Ring-Wraiths from the Lord of the Rings.

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%A2%E3%83%B3%E3%82%B0%E3%83%9E%E3%83%BC%E3%83%AB%E3%81%AE%E9%AD%94%E7%8E%8B

The Maō from Chain Chronicle x Maōyū is the same Maō in Archenemy and Hero (aka Maōyū).

… though “Archenemy” feels strange here, as in the first chapter/episode, this Maō and Hero become allies to save the world. She’s also the leader of an alliance of Demons (魔族 Mazoku), and while the humans think she is evil like her predecessors, she and Hero are (secretly) trying to manipulate for an end of the war with minimal suffering and conditions for lasting peace.

“Archenemy” is the only official English translation, but TV Tropes refers to her as the Demon Queen in descriptions, and this is also the translation I prefer. The alternatives (Archenemy? Demon King? Overlady? Maou?) are just too awkward, especially when she and Hero are both idealists and dedicated to each other.

P.S.: In the first chapter the Hero (勇者 yūsha), expecting the Demon King to be male, was surprised to find the Maō to be a woman.

So there was this playing with expectations from the beginning.

It is interesting seeing that outlier example from Disgaea, since having played several of those games I do recall that in the vast majority of instances it’s indeed translated as overlord. Maybe they just made it King Krichevskoy for the alliteration or something. That series was the first thing that came to my mind from the subject of translating the word maou.

Oh yeah! Shin Megami Tensei IV had 魔王プルート, rendered as Pluto the Tormentor, and 悪魔王ルシファー, rendered as Demon Lord Lucifer.

In Japanese Lunar 2, Lucia is romanized as Lucier. Clearly going for a COULD be a maou feel. I don’t recall it ever being anything but obvious that she isn’t in the actual game however.

The Bravely Default games have maō, but the word there refers to a whole category of monsters rather than an individual. It was translated as Ba’al, possibly just so that the second game could make jokes about the “Ba’al Busters.”

Nope, it’s literally the same, Magic Emperor. 魔法皇帝. However! The hordes he commands are the Mazoku, one of the same ambiguous “evil clans” that a Maou would rule over. Vile Tribe in the US translation’s case.

Yea, Ganon’s a mess. You’re a bit misleading with that ALttP description though; it says “闇の魔王” which is Demon King of Darkness”, but you just say he’s called a maou in Japanese and Evil King of Darkness in English, as if the localisers added the darkness part. Anyway, following OoT, Ganondorf is once again called Daimaou in Twilight Princess, but he’s called Dark Lord in English. Spirit Tracks and Skyward Sword finally let it rest and kept it as Demon King when describing Malladus and Demise.

Thanks! I hadn’t considered that that could misleading so I updated it.

I remember Granstream Saga for the Playstation had some kind of evil spirit thing called the “Mah Oh”. Was that possibly a Maō?

Yeah, it definitely sounds like it from your description.

You might want to take a look at the more recent Tales of games – I’m not at all familiar with the Japanese translation, but Zestiria and Berseria both have a concept of a “Lord of Calamity” that I feel like was probably maou prior to translation. Could be wrong, though.

In Slayers, they have both “mazoku” which are a race of evil creatures who only seem to desire destruction and a return to nothingness, and their rulers, the “maou”. In the TV series, they translate “mazoku” as “monsters” and for the ruler, they just call him “Dark Lord Shabranigdo”. In the movies, which were translated by another company, they just call “mazoku” as “demons” I believe.

Another example I can think of, though basically touched upon by your post, is Dragon Quest, which is full of struggles between mazoku and the maou and God/Goddess. Psaro is an interesting example of it. In the English localisation for the DS and smartphone remakes/ports, he’s called “Psaro the Manslayer” to really drive the point home that he’s not a nice guy. I wonder if he had an equivalent title in Japanese, or if he was just called a mazoku?

Ah, a point I forgot to make is that in Slayers, the “mazoku” stand in direct opposition to the “shinzoku”, which I thought was very interesting. I don’t remember if they were ever referred to directly in translation, but it would be interesting to see the many forms of shinzoku as well.

The manslayer title was “Death Psaro” in the Japanese version.

The anime Eto Ranger features a villainess known as “Jarei-Ou Nyanma”, which the fansub floating around translated as “Jyarei *King* Nyanma”, which consistently bothered me. Guess I know the reason why it was translated that way though! Going from the Japanese Wikipedia, The name’s written in Japanese as “妖魔王・ニャンマー”, and “妖魔” by itself usually reads “youma” or ghost or demon. So we have a maou with an unusual reading it seems.

This is a great blog! I have the Earthbound book on my shelf and I can’t wait to read it. 🙂

I played Harvest Moon 64 a lot as a kid, and I remember that one of the villagers’ stock phrases when you talked to him was “Let’s both do our best.” Do our best at what? Just in general, I guess? I’ve since heard variations on this sentiment in other Japanese translations (usually with a bit more context), enough to suspect they’re translations of a specific Japanese phrase that doesn’t have a real English equivalent. If you could provide any insight into that, it would be really interesting.

Ooh, that’s a really good suggestion. Thanks!

The translation for Record of Agarest War Mariage [sic] uses “Archfiend” for Eclipse, the body snatching evil dude that each generation’s hero must defeat. I thought that was an good solution, but I checked and the original title was 魔神. “Archfiend” could still be a useful option for 魔王.

This reminds me of the Kyros the overlord and archons in the pc game tyranny.

As seen here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lhCy6rAtqZg

I wonder why that term isn`t used more.

Thanks for the interesting article. I am curious if you would be interested in doing one on the seemingly related “makai” that I see come up sometimes in connection to video games and anime. It seems like it’s usually translated as something like “demon world” but with different connotations from “hell”–the best way I could describe what it seems to mean based on uses I’ve seen is more like a malevolent/gothic version of a “fairyland” or “wonderland”, more of a fantasy realm than an afterlife. Contrast to “jigoku” which seems more in line with the Western concept of “hell” from what I can tell.

Some enlightenment would be appreciated!

I wonder whether there’s jokes involving this word and Mao Zedong the former Chinese dictator. Even though it’s most certainly a pure coincidence, this man was quite evil on his own and would have been a good choice for a “Maou”.

Looking back, I now wonder if the Tyrant from Resident Evil series was named after the development team’s attempt to translate the term internally. The monster is still referred to as “Tyrant” in the Japanese version, but given that the game takes place in America, it’s possible that the writers decided that the scientists would name their strongest zombie after an English equivalent of “maou” and that’s the word they came up with.

Am I the only one that’s amused that the localization of Shadowgate essentially turns him into “Warlock, the Warlock Lord”?

I’m surprised that Odin Sphere didn’t make it into this list. There’s a clear use of ‘Mao’ in the Japanese voiceovers when referring to who’s known in English as ‘Demon King Odin’

Of course, the spiritual translation for something that’s used the same in literature (but not video games, due to a divergence in genre fiction and stuff) is Dark Lord, which carries the same meaning and implications

I just found this website, and I find it amazing.

Anyways; I’m late on this, but there is a scene in the anime “Fairy Tail” where the main character, Natsu Dragneel, pretends to be evil, and calls himself “Daimao Dragneel”.

I recently went down a Google hole and stumbled upon the knowledge that in Japanese, the song “In the Hall of the Mountain King” is called “山の魔王の宮殿にて”, lit. “At the Hall of the Mountain Maou”. I suppose a troll king isn’t any less of a maou then Laharl, the maou from Maoyu, or Velvet Crowe. Or David Bowie, for that matter.

Oh, another one! In Kid Icarus Uprising, the player fights a maou. That wouldn’t be interesting in and of itself, except the stage they’re fought in begins with the protagonists discussing how overdone evil maou are and hows surprised to see one played straight in this day and age, so the translation had to communicate a similar feeling. They wound up going with “Dark Lord”.

It’s also a good example of how flexible the word maou is, as the maou in the game is a pretty low level henchman (not a king) and one of the only enemies in the game who ISN’T some kind of demon or monster, but they’re still a maou.

NieR Gestalt/Replicant changed the enemies from “demons” to shades, and the “demon lord” to the shadowlord. It’s certainly more unique, but I feel it loses some of the directness that the original has – NieR uses such direct terms because it’s a deliberate send up/deconstruction of the classic JRPG plot (admittedly, as an action RPG instead).

Regarding Piccolo from Dragon Ball, his Japanese title, “daimaō”, was translated in a similar manner in the Finnish version of the manga as Ganon’s in The Legend of Zelda. It was translated as “pimeyden ruhtinas”, which translated into English means “the prince of darkness”. What I find interesting, though, that apparently the English manga translation used the term “king” only about Piccolo Senior and not at all about his “son”, or the young reincarnated version of himself, whereas the Finnish version referred to both versions as “pimeyden ruhtinas” consistently.

In Kamen Rider Zi-O, two people from the year 2068 (Geiz and Tsukuyomi) travel back in time to stop the main character (Tokiwa Sougo) from becoming an evil omnipotent dictator known as Ohma Zi-O, who is called a “maou” by them, and also by Woz (a narrator-type character), who humorously refers to him as “waga maou”.

Anyway, one fansub renders “maou” as “demon king”, while another renders it as “overlord”. I prefer “overlord”, since Sougo isn’t a demon, and it fits what he will become in the future.

I’m disappointed that you didn’t attempt to go to the root of it all…the Chinese Kanji.

The “Ma” thing is a Chinese loanword.