Many moons ago, Steven asked a question about the Corpse Party translation for the PSP. I’ve never played it but it’s always looked like something right up my alley, so this is a good chance for me to finally take a peek at the game!

Here’s Steven’s question:

Here are just some choice quotes from Corpse Party (some profane stuff here):

- ”I’m gonna butter up my pooper with it real good!” – From the character Seiko during CH1

- ”Anyone who takes stuff posted on the net and swallows it wholesale is a fucking dumbass. A total retard.” – From the character Naho later in the game.

I was just wondering about the localization because while it is grammatically great, and flows really well (while being able to maintain the scary atmosphere the original must have had), some lines just seem to be ad libbed based on the mood rather than what the character says.

Mind you there is 100% voice acting in the game, but my Japanese isn’t really good enough to tell if it’s what the character actually said in the original version. I would definitely say that it and it’s sequel are known for their incredible localization though – especially since it’s a horror game with minimal visual representation.

Since I’m not familiar with the game it took a little detective work to find this line of text in both versions of the game, but luckily it wasn’t too bad – it sounds like this “butter up my pooper” line made a big splash with English fans, which helped a bit. So, for reference, here’s the full scene in both versions of the game:

And here’s the actual line in question:

|  |

| Japanese release | English release |

And here’s a look at the text, side-by-side for easy comparison:

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Version |

| Seiko: H-hey, Naomi. | Seiko: H-hey, Naomi? |

| Naomi: Hmm? | Naomi: Hmm? |

| Seiko: Do you have any butt medicine? The kind you gotta rub on. | Seiko: Do you have any of that ass medicine on you, by any chance? You know, the smeary stuff? |

| Naomi: Huh, again? | Naomi: What, again?! |

| Seiko: Yeah…… My butt’s kinda been giving me some trouble lately, you see… | Seiko: Yep. My butt’s been drier ‘n a desert since we got here. |

| Naomi: Well, I do have some ordinary ointment. Here. | Naomi: Well, I’ve got some antibacterial cream, if that’ll work… |

| Seiko: Thanks! Okay, I’m gonna go apply a bunch real quick! | Seiko: Thanks! I’m gonna go butter up my pooper with it real good! |

| (Seiko walks off the screen for a few seconds) | |

| Seiko: Yay! ♪ ♪ | Seiko: Yaaay! |

| Naomi: ……You could show at least a little embarrassment, you know. | Naomi: …Do you have any shame at all? |

This is more or less what I was expecting before going into this – the English version is a punched-up version of the Japanese text, but in terms of content it’s about the same. For the most part, if you ever encounter writing that sounds like this in a translation, you can usually assume the Japanese text is actually quite a bit tamer.

There’s a lot to say about the topic, but to just touch on it quickly, straight translation from Japanese to English often results in English text all having the same “tone”. As a translator, this is sometimes frustrating; the original Japanese text usually has so many distinguishing characteristics that get lost – things like gender cues, age cues, background cues, status cues, relationship cues, and the like. So the natural desire is to try to take these “monotone” translations and re-inflate them with character and other distinguishing characteristics.

This process usually happens one of several ways:

- The translator might try to insert other types of characterization to compensate for what’s lost in translation. This is usually the cheapest, quickest, and easiest route, but it requires the translator to be really creative and willing to divert from the stuff they just translated. For instance, a lot of my fan translations were like this, such as Bahamut Lagoon and much of MOTHER 3. Some of my professional translations I’ve done for agencies were like this, too.

- The straight, literal translation might be given to a punch-up writer or editor. As a personal example, many years ago I did the straight, literal translations for the Shin-chan anime series for FUNimation, and those translations were then rewritten and punched-up like crazy by Evan Dorkin, Sarah Dyer, and some of FUNimation’s own writers for the English dub that aired on Adult Swim:

The level that a translation gets punched-up can vary greatly. Sometimes it’s done just to make things sound less like “translation-ese” and more like natural English, and sometimes it’s to completely change everything and repackage it for a completely different target audience. With game localization, punch-up is usually somewhere between those two extremes.

- The translator might try to use what I currently call “reverse localization”, which is really a topic for a future article… But as an example, let’s say you’re translating a scene from Japanese to English. The normal mindset is to just translate like normal – try to recreate the Japanese text in English. But with “reverse localization”, you instead pretend that the scene was originally written in English first, and then translated into Japanese. And now you’re looking at that Japanese. So your job is to deduce or figure out what the original English text might’ve been first.

It’s weird and tough to explain quickly, but it’s an interesting approach that only really good, experienced translators can pull off. We’re talking Level 99 Black Magic Translation Wizard stuff here. Some of Alexander O. Smith’s translations give off this vibe to me, as an example.

I’m sure there are a few other approaches to the re-characterization process, but those are the main ones that come to mind right now.

Anyway, off the top of my head I can’t recall how XSEED handles things, but I get the feeling they use a combination of all three, but with a little more emphasis on the use of punch-up writing and editing. I’d actually love to know more about how different companies handle this aspect of game localization, that’d be an amazing topic to research sometime!

All that said, the “butter up my pooper” line seems to be legendary among Western gamers now, but it’s not even really a blip to Japanese gamers. It’s always amazed me how that happens – another example is the good ‘ol spoony bard line from Final Fantasy IV!

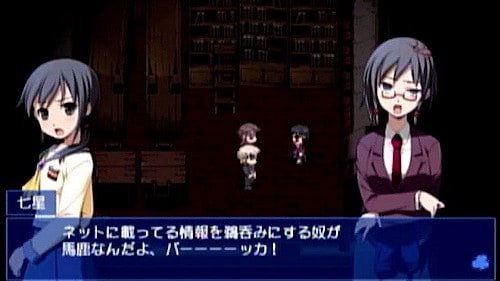

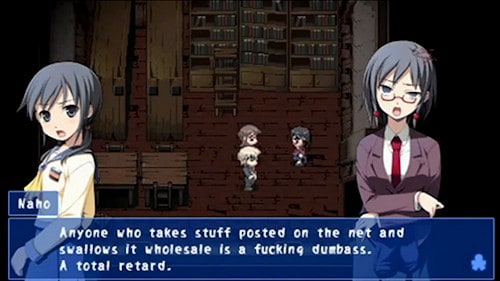

So, getting back to the question, there was one other line to look at – one near the end that’s surprisingly harsh in the English version. It took some digging up, but here’s the full scene in both versions of the game:

Here’s the exact line in question:

|  |

| Japanese release | English release |

And here’s a look at the line side-by-side for comparison:

| Japanese Version (basic translation) | English Version |

| Naho: Anyone who accepts info on the net without thinking is an idiot. An IDIOT! | Naho: Anyone who takes stuff posted on the net and swallows it wholesale is a fucking dumbass. A total retard. |

Insults in general can be tough to handle well in translation, and this is one of those cases. Naho doesn’t seem to be speaking as harshly in Japanese as she does in English… but in the Japanese version of the game she normally speaks in a polite, formal way until this scene, when she suddenly switches to the rudest and crudest speaking style. So it sounds like the use of “fucking dumbass” and “total retard” in the localization is an attempt to convey that sudden jump in speaking style. This sort of speech style switch is another obstacle in Japanese-to-English translation, so it’s really interesting to see how it was handled here.

Whew! So even though we looked at just a mere two lines in the translation, hopefully that helps shed some light on why these translations were probably phrased the way they were and why there’s actually more to translation than just words!

It’s kind of interesting (and somewhat sad) that lines tend to only be memetic within the language they were written in – I guess there’s often something intrinsically humorous in the wording that makes it catch on that often gets lost in translation, kind of like Golbez’s いいですとも! line in FF4 (http://dic.nicovideo.jp/id/224221 – This page also has a direct comparison with the EN translation, and notes with a tinge of disappointment that it didn’t really take hold here).

Come to think of it, whenever a translated line catches on like that, it tends to be because of a translator taking liberties with the original work. Take JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, for example: despite the fact that just about every line of the manga is meme-tier in the Japanese fanbase, one of the most memetic lines in the English fanbase (barring ZA WARUDO) is http://imgur.com/AQA54MO , a very punched up translation of the lesser known original (http://imgur.com/CyDC9ky). Next to that comes the hilarious Duwang Part 4 translations, which were popular enough to inspire a fansub of the 2012 anime in the same style.

Then again, the internet latches on to weird things most of the time, so it can’t be helped. ( ´∀`)

Why is “いいですとも” a meme in Japan?

The short version is that Golbez normally speaks in a rough and badass sort of way and いいですとも! is surprisingly formal and polite coming from him. Think a normally nice guy suddenly calling someone a dumbtard but backwards.

In this case the best way to explain it is to translate it as “Indubitably!” Very weird to hear coming from him after his badassery the entire game.

I find it sad that “punched up” vulgarity in English often involves using a lot of swear words, like North Americans only really care about dialogue if there’s loads of cursing in it.

I hope the comparison question I sent in November proves more amusing. XD

Not much way out of that – the most effective way to highlight the difference in politeness scale in Japanese words that otherwise mean the same thing is to use swear words, more-or-less the English equivalent.

I know no Japanese whatsoever, though – so I wouldn’t know if the effect is EXACTLY the same.

Yours might be the funniest comment I’ve ever read on this site.

Ah, Mr. Alexander Smith worked on FFXII and Vagrant Story, huh? That’s good to know, I loved the translation in those two games.

He was involved also with the first four Ace Attorney games, and possibly Ghost Trick. I loved his work. People say he would try for these games full of references to find the closest English cultural equivalent for each, but I have seen people despising those particular translations for this very reason… localized too much for their purist preferences.

If only Goemon and Segagaga could get the same kind of translation, since they rely heavily too on puns and real-life jokes.

If only Goemon could get any love at all right now. C’mon Konami.

Konami reduced Goemon, long ago, alongside Twinbee and other once-stellar franchises, to skins for their pashislot cabinets.

Just to get an idea, the once in the Japanese all-time classics top ten franchises, Tengai Makyou, is being now licensed by Konami as a theme for a GREE card-game.

The lesser said about Konami, the better.

And Goemon had all four Super Famicom games released on the Wii VC but they didn’t deem it worthy or release here aside from the first (despite .. Rondo of Blood, and Doremi Fantasy Milon no Daibouken among others being published in US/PAL Wii VC). The fan-translations for the remaining three SFC games (I didn’t count Ebisu’s spin-off since that’s something different) are stuck currently in development hell. Which is a shame.

Ah… Konami is just sad, being kept afloat by Yu-Gi-Oh!, Pro Evolution, the corpses of Metal Gear and Castlevania.

When was the last time you saw Vic Viper? Or Goemon? Contra? Anyone?

What I find frustrating is that when Konami bought what was left of Hudson Soft last year, I assumed they were going to keep the company on some sort of life support. Unfortunately, aside from a possible new East of Eden game coming out for mobile phones in the future, it looks like Hudson’s franchises have gone the way of the dodo. It’s REALLY weird to think Bomberman is no longer with us.

Most of Hudson’s staff went to Nd Cube, so maybe if they ever decide to take a break from Mario Party, they’ll make a Bomberman-alike.

Ugh. Don’t remind me of Pachislot. It’s depressing how so many once-great companies are reduced to either making cheap mobile games or trying to just extract more cash from consumers with Pachislot. (For those not in the know, Pachislot is NOT Pachinko. They’re basically slot machines.)

*me looks wistfully at IREM and Sunsoft*

Actually Alexander O. Smith only worked on the 1st and 4th game.

Janet Hsu directed localization starting from the second game (where all the pop culture references started appearing), if you look carefully at the dialogue between the first 2 games you can see the difference in translation approach.

That “reverse localization” concept is an interesting one to me, is that a technique you came up with or something taught to you?

I can’t really remember, I think I first heard about the concept from some translation theory writing/talks a long while back. I think it was in the context of translating poetry, but it seems like it could work entirely well with game localization too.

The way it’s worded is pretty convoluted, but if I understand it correctly, this is my personal baseline definition of fictional translation.

The idea is that you’re recreating the work as if it was originally written in English. You understand the characters and the tone and the author’s writing style and you write to that. The literally wording is a loose guide at best.

In the pooper example, above, the butter up my pooper line does a much better job of conveying the jaunty phrasing and tone than the more ‘accurate’ translation the author of this article is providing. (I’d be willing to bet they’d be doing a more colorful translation of that themselves if they were translating that for anything other than educational purposes.)

Recreating the work as if it was written in English is a lot more difficult. If you’re tired or not in love with the work to begin with, it’s easy to get lazy and not go that extra mile. I’m certainly guilty of that at times. But when I read back through the translation, I can always tell which bits I was engaged with, and where I’d tuned out. And I bet readers can tell, too; but they often just assume this part wasn’t well written to begin with.

…didn’t know much about “the author of this article”, did you?

The concept of a “reverse localization” is interesting. I know as a writer I’ve toyed with something similar (writing text and dialogue in English, but done in such a way to convey that it was written in a different language first and then translated), but it’s a fascinating idea to use it for actual translations! I know a couple translations I’ve seen that kind of have that feel. There’s a 3DS eShop game called Crimson Shroud that reads very much like a traditional American or English swords ‘n’ sorcery novel. For a game originally written in Japanese to have a localization that feels like native English novel prose, that’s incredibly impressive! I’ve read some visual novels translated from Japanese before, but most of them still read more like dialogue than prose, or don’t feel particularly “novel-y” (like the Zero Escape series).

There’s also an obscure-but-great RPG (I know an awful lot of obscure-but-great RPGs) called Monster Racers for the DS that has a pretty excellent localization, and one particular moment in it stuck out as so sublime that I have no idea how it was translated, because it feels like it should’ve been in English all along! That particular moment is in the name of one of the monsters in the game. It’s a wolf-like creature with a flower for a tail, which also happens to run everywhere backwards–it’s kind of a pushme-pullyou, and the “flower” is as much a head as the one that’s got teeth! The English name given to this creature is “Flowrwolf”–not only is it a flowery wolf, its a PALINDROME, reflecting the the two-headed nature of the creature, and it works beautiful in English! I don’t know what better name you could give to a flowery wolf–indeed, it almost seems like it was BASED on that palindrome–so really, it took me by surprise how perfect its name was! Hmm…

Holy crap that palindrome is amazing 😯

Is there any way you can get a screenshot of it? I just it by itself deserves a post of its own!

I looked to see if anyone had taken a proper screenshot of it off an emulator or DS screencapture device, but I couldn’t find one. I would take some myself, but this particular critter actually appears really late-game; the second to last area, in fact. o_o I did, however, take an off-screen snap if you don’t mind the shimmery quality:

http://img.photobucket.com/albums/v46/Freezair/Flowrwolf.jpg

Sadly, I wouldn’t even know where to begin looking for the Japanese name of this critter!

Checked a Japanese Wiki for the name. Flowrwolf is called Bush, ブッシュ.

That’s more clever than the Japanese one then!

Reminds me of the Pokémon “Girafarig,” which is also a palindrome, and… well, the creature is part giraffe and pretty obviously part farig: http://bulbapedia.bulbagarden.net/wiki/Girafarig_(Pokémon)

Alomomola is also a palindrome, but is 100% nonsense-word.

Not entirely nonsense: Alomomola is based off an ocean sunfish, and “Mola mola” is the scientific name of the ocean sunfish (and one of the common names it sometimes goes by; “mola” for short).

I stand corrected. It sounds like such gabbletygak I just assumed it was. 🙂

You also have Eevee and Ho-oh.

I did not know “farig” meant anything, but after looking it up… Holy crap, that’s amazing. It just fits.

Most interesting. I had vaguely heard of this game through word of mouth. That’s impressive localization work.

I’m really new to Japanese: Why all caps over maintaining the enlongagedness (Like “Stuuuppid!”) for the basic translation?

Elongating it in translation is a totally okay choice too. It’s common to hear “baaaka” elongated in normal Japanese though, and it’s essentially just emphasizing the word, so I emphasized it with all-caps in my sample translation above.

Thanks.

I’d just like to point out take the person solely responsible for (he did the entire localization of the first game in his spare time, solo, when he asked if they’d let him do it (they couldn’t spare any other staff due to other projects)) the localization of both game’s, Wyrdwad, hangs out and answers peoples questions over on the gamefaqs forums, and I vaguely remember him saying why he went with the pooper line when someone asked him about it.

Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together in particular is an has amazing writing. Great work of Alexander O. Smith.

Kind of reminds me of the extra charm they put into the localization of Recettear – though this one focuses on punching up the harshness whereas Recettear’s edited text consists of adding a cutesy factor to it.

The problem with the “retard” line is that, to many people, that word is a level of offensive above normal swearing. It seems odd for a really polite person to use that word as profanity for emphasis. It’s just on a different level than “fucking dumbass,” which is mere vulgarity.

It’s really hard to explain this correctly. I’m not saying you can’t call people “retarded,” just that I think the translator is treating it like a mild swear, when someone who is really polite would probably be politically correct, and see it as far worse than “fucking dumbass.”

It’s also worth noting that the word “baka” is a LOT stronger than anime fans assume. Anime tends to use it pretty casually, and a lot of people, myself included, toss it out lightly once they get to Japan, and are rewarded by seeing people flinched like you punched them. I think this translation accurately reflects the tone of the original; this sounds like the speaker being as harsh as they know how to be.

In English, it sounds a lot more like they suddenly turned into a twelve-year-old, not like they’re the same character being suddenly and comically rude.

Well, the characters ARE school kids, and in this scene she’s revealed to be a nasty one hiding behind a nice girl facade so it feels appropriate to go above “rude”. Western players probably wouldn’t bat an eye at “idiots!” since that barely qualifies as a swear over here, especially if you’re not directing it at a specific person.

There is not a problem with the “retard” line. In this part of the game, the character reveals her true self, and then you realize that she is probably one of the hugest jerks in the history of anime. The game even changes her expression to that of a japanese delinquent to reflect this.

“Baka” is already a strong word in japanese, yet “Baaaaka” is even stronger. She basically calls those people morons.

The problem in the English script is that instead of sounding like a jerk out of nowhere, she suddenly sounds like a child in that phase of life when they’ve very recently begun peppering their language with crude words.

It’s the sort of thing you’d more often see in a fan translation, where it’s likely some of the people involved were very recently in that stage of life themselves.

XSEED tends to like to throw vulgarity into their translations from what I can gather.

I can’t read Japanese at all, of course, which means what I say is likely invalid, but every time I see a line like that in one of XSEED’s releases, it just feels ‘off’ somehow, as if the character became a puppet operated by the translator and editor, speaking the translator’s words instead of their own, if that makes any sense.

“Pooper” is very early 4chan lingo, incidentally.

Speaking of XSEED, it might be interesting to see a treatment of Little King’s Story for the Wii. Problem is, I can’t really think of anything specific, just because a whole lot of amusingness that had to have been localized.

For one thing, the aliens who use leetspeak. There’s a letter, for one thing, and every time you dig a UFO up.

The New Island language, whatever it’s called. In a move reminiscent of Chulip, this language uses real words, but defines them far differently.

A lot of the item names (Neil de Grass, anyone?) and Gourmet Book descriptions (“…tastes like teen spirit”).

Verde calls someone (the king, I think) “Galactus”, at some point.

Liam hears “flying machine” and thinks “frying machine”.

The intro contains unsubtitled audio narration. Part of it, “And then somehow, in some such way,” sounds… odd.

Oh, and the basic kind of enemy, the Onii. Now, I know a tiny bit about “oni”, and that’s probably at the heart of what’s intended, but when I see “onii”, I think “older brother” or even possibly “male who is older, but not too much older” like it seems to be (but I could be way off base there), so it makes me wonder if a connection between “oni” and “onii” is intended.

On a related note, there’s an enemy that hula-hoops a ring around himself as he walks. He’s called an Oniion Ring.

Lots of things like that.

One difference that should be pointed out before you go wondering what the Art Pieces are called in Japanese: They’re not the same Art Pieces. That’s right, the JPN and PAL versions have a different set of 100 Art Pieces from the NTSC version. Each pair with the same number is in the same place in the world, and acquired the same way.

So, if you feel like this interests you enough to either get the game (if you don’t already have it) or track down playthroughs and/or screenshots to make comparisons, I’d be interested in seeing what you have to say about them.

(As far as the gameplay, the core mechanic is like Pikmin, in that you have a central character with a bunch of characters that you can send away from you to perform tasks like fighting, digging, building, destroying, and so on. There aren’t any innate immunities, though you may get equipment that grants it. It’s pretty fun overall, but the building and destroying can involve a lot of waiting.)